Cornershop

This UK band brought some much-needed multiculturalism to white rock ‘n roll America in the ‘90s

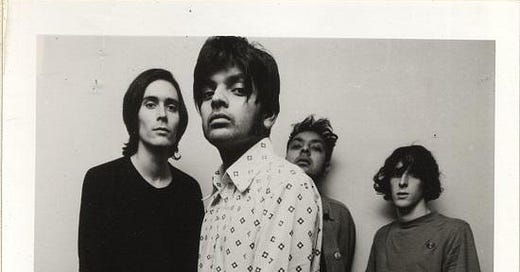

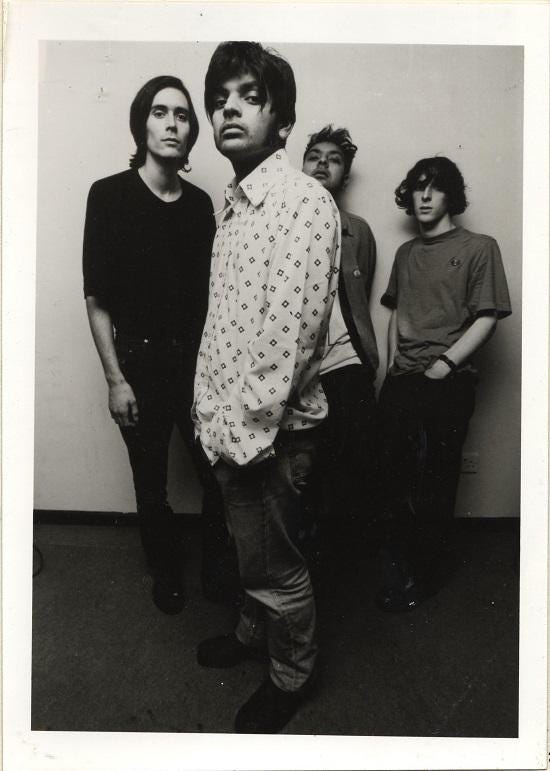

Tjinder Singh and his band Cornershop are onstage at Spaceland, an indie rock dive in L.A.’s Silverlake district. Clad in old jeans and a purple t-shirt, with thick, dark hair falling into his face, Singh looks tense as he cradles an acoustic guitar and begins to strum a dark, velvety, minor chord. Soon, sitar and tamboura join in, their separate tones weaving a dense, warbling drone. A percussionist pounds on a large bank of bongos, tablas, bells, and chimes, as the band locks into a deep groove. Standing ramrod straight, Singh starts to chant. Unfamiliar syllables clang together, dancing in and out of the groove as the ecstatic din builds behind him. His dark eyes blazing with the intensity of a cleric, Singh looks like a man struggling to communicate in a language no one can understand.

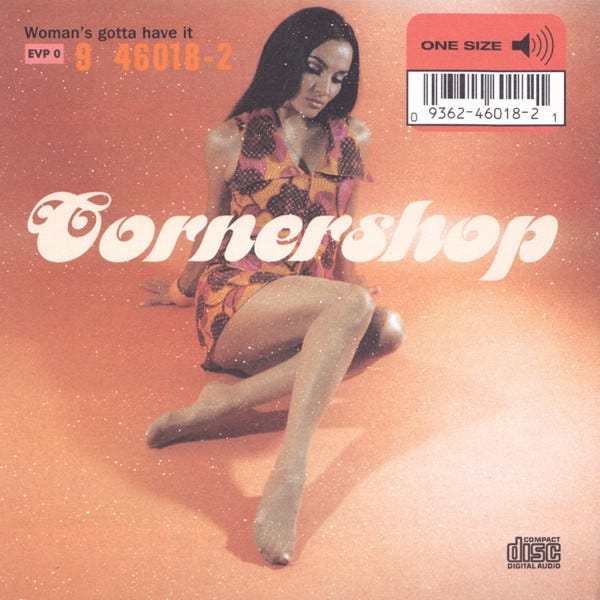

In fact, that’s exactly what Singh is doing. The lyrics of the song, “6 A.M. Julander Shere,” from Cornershop’s Woman’s Gotta Have It (Luaka Bop), are delivered in Punjabi. And it’s a safe bet that few, if any, of the hip young Angelinos in the audience speak even a word of the North Indian language.

Fortunately, you don’t have to be fluent in Punjabi to understand Cornershop. The band’s music—an organic blend of scrappy guitar rock and the exotic tones and textures of Indian ragas and Punjabi folk songs—speaks eloquently for itself. The 10 songs on Woman’s Gotta Have It describe a world in which technological advances and waves of immigration render traditional notions about borders, both political and cultural, increasingly archaic. In Cornershop’s music, Hindi religious chants, washes of looped feedback, aggressive guitar riffs, and dense layers of African and Indian percussion coexist in lo-fi cacophony. With lyrics in English, French, and Punjabi, the group’s musical mosaic is as meaningful in Los Angeles as it is in the group’s hometown of London—or, for that matter, as it would be in any of the world’s major cities perched easily on the edge of the 21st Century.

Standing at the center of this heady mix is the 28-year-old Singh. A first-generation Briton born into a tight-knit Sikh community near the industrial city of Birmingham, he straddles the same disparate worlds as his music. He is among the first of his generation to resist intense community pressure to go into business or shopkeeping, instead choosing to pursue a life in the arts—a decision which has caused considerable grief for Singh and his immigrant community.

His father, a schoolteacher in the Birmingham suburb of Wolverhampton, refuses to see Singh perform. Instead, Singh says, his father clings to his wish that his ambitious son choose a less risky career path. It’s for that reason he named his band Cornershop. Yet Singh has not been embraced by the Anglo world, either. Despite several generations in their adopted country, South Asian immigrants continue to bear the brunt of a particularly nasty strain of British racism. Even in the ethnically diverse Archway neighborhood of London, where Singh lives in a flat above a fish and chips shop, he regularly faces verbal abuse and even physical attacks from people put off by his dark complexion and his white girlfriend. It’s a compelling paradox: Even as Cornershop’s music embodies the increasing irrelevance of cultural borders, Singh’s story demonstrates that the old boundaries still assert themselves with brutal intensity.

“It was always there, in the air—from being chases by motorbikes to being beaten up just for the sake of it. It was always there.” Singh is sitting in a crowded Mexican restaurant in a Sunset Boulevard mini-mall. Between mouthfuls of huevos rancheros, he explains what it was like growing up in England. Exhausted from a late-night party following a gig opening for Porno for Pyros, he answers questions politely but without much enthusiasm. Ben Ayers, Singh’s songwriting partner in Cornershop, sits beside him and is even quieter. It’s clear that both have quite a bit of partying to sleep off.

Nonetheless, Singh patiently explains how, as a kid, racism was a constant concern. And, in many ways, he adds, it wasn’t much easier in his own community. Like many English kids, Singh and his brother, Avtar, were interested in playing cricket, listening to rock music, and keeping up with the latest fashion trends—all of which were frowned upon by Sikh immigrants who seemed only to value the qualities of hard work and enterprise.

But Singh says he knew from an early age that, just as his father had left his native India, he would have to leave his cloistered community. As a child he would often sing and play the dholki, a small Indian drum, during service at the local Sikh temple. “Half the building was owned by the Black gospel church,” he recalls. “We used to open the door and listen to their music. It was great, good old rousing shit. And they would pop into our section as well.”

But Singh didn’t start making his own music until 1988 when he met Ayers while attending college, and the duo began bashing out songs on acoustic guitars. “We banged around on old pots and pans and stuff,” says Ayers. Eventually, Singh got a bass and an old amp. Ayers got a drum machine. They began adding sitars and samplers, and things slowly fell into place. It became apparent to Singh that the band could use music to mirror the racial tension he had grown up with.

“Asians in England are seen as not contributing anything to the community, as keeping to themselves,” Singh explains, aimlessly stirring his coffee. “We wanted to use instruments like the harmonium or the sitar to represent how Asians are seen as being passive, just living their own lives. And on the other side, with the guitars, we wanted to just fuck it up, to show how Asians really feel. We were trying to counter the rage felt by Asians with the serenity of Asian culture.”

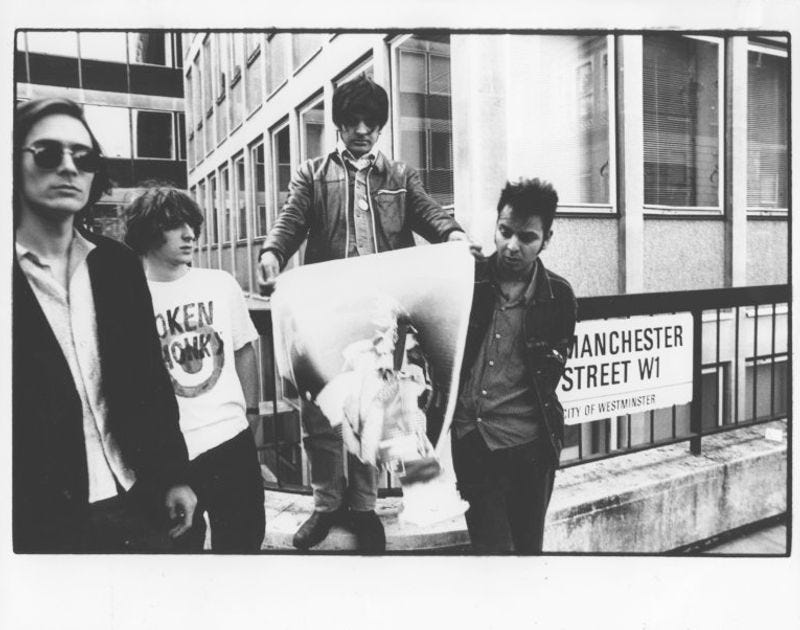

Cornershop released a series of 7-inch singles but didn’t gain notoriety until 1992, when the group launched a high-profile assault on—of all people—Morrissey. The Smiths’ former frontman had been flirting with skinhead imagery and writing allegedly racist songs, such as “National Front Disco” and “Asian Rut.” Cornershop burned pictures of the singer onstage and at a press conference in front of EMI Records’ London office—which many in the English music press dismissed as a cheap publicity stunt.

“Morrissey was mouthing right-wing sentiments,” Singh says. “It was very dangerous, especially at that time. It was a very tense moment. There was a lot of hostility, and there had been some racial killings. We still stand by what we did. And we’d do it again.”

Nonetheless, Singh bristles at the notion that he’s some kind of role model or spokesperson for the Asian community. Cornershop, he insists, “is just a reflection of what I’ve gone through. A lot of people say there’s a lot of pressure on my shoulders, because a lot of Asians will be looking up to me. I’m not speaking out for no one else. I’m just speaking out for myself. I’m just reiterating what happened to me. I don’t want any part of the rock ’n roll thing,” he says, using a tortilla to mop up the last bits of his breakfast. “And I don’t want any part of the role model shit, either.”

We pay the check and head out into the bright summer sunshine. Singh and Ayers appear ready for little more than a nap. But they perk up at the suggestion of stopping at a few thrift shops on the way back to their hotel.

“We can’t afford to buy new music,” Singh says excitedly. “All our best stuff comes from charity shops—choir music, children’s records, bird songs, sound effects, stylus-testing records, classical music, ’20s jazz, ’70s reggae, Punjab folk music, and a lot of hippie shit as well.”

The first couple of stops turn up nothing. But at the Children’s Hospital Thrift Store in East Hollywood, Singh and Ayers head straight for the racks of dusty used records. Rifling rapidly through the stacks, Singh pulls out a French record called The Singing Nun and sets it aside. “Can’t pass that,” he says with a grin. Singh leaves Ayers and the records behind and moves quickly through the store, fingering a dark tweed suit on a rack, asking a salesman to take an old vintage Kodak camera from the glass case. In the luggage section, he picks out a fine-looking straw suitcase. “For my CDs and guitar leads and stuff,” he says. After some confusion over American currency, Singh pays for his goods and we climb back into the car.

Soon we’re stuck in traffic, idling near the intersection of Sunset and Vermont. Long, slender palms arch over the wide, congested boulevard, and in the distance the Hollywood sign peeks through the summer smog. Salsa music, dense with percussion and punctuated with shrill trumpet riffs and raucous singing, pours from the car stereo.

Singh sits in the passenger seat with his purchases cradled in his lap, smoking a Marlboro Light and nodding his head to the unfamiliar music.

“This is some kind of dream, isn’t it?” he says, looking out the window at the scenery. “Some kind of dream.”

Larry Kanter is an editor in Brooklyn, New York who also plays bass in the punk-indie trio Resistor.

Note: Republished with author Larry Kanter’s permission, this story originally appeared in the July 1996 issue of Option. Published by Scott Becker, this print music magazine ran from 1985 to 1998 and was edited by a series of folks, including Richie Unterberger, Mark Kemp, Jason Fine, Steve Appleford, Erik Pedersen, Barbara Jordan, and Scott Becker. Kristin Bell was Option’s art director. This is the first time this story has appeared online. To read more of Option’s back catalogue, buy the anthology We Rock So You Don’t Have To: The Option Reader #1, edited by Scott Becker, or browse Rock’s Back Pages.

A splendid band. I saw as part of John Peel's Meltdown, in the 90s, with Gorky's Zygotic Mynci supporting. A good gig!

One night, Right after “Brimful of Asha” came out, my girlfriend and I pulled up to a light. The guy in the car next to us was absolutely losing his mind to the song. Windows down, volume up, and signing his Iungs out. 100% bliss. Couldn’t have cared less that people were next to him. It was just that good of a song.