Depeche Mode, Flannels, and Van's

Going from punk to synth to rock at the dawn of the alternative era

1989 was the year of the Exxon Valdez spill. It was the year the Iron Curtain first cracked. And it was the year I started high school as a huge Depeche Mode fan.

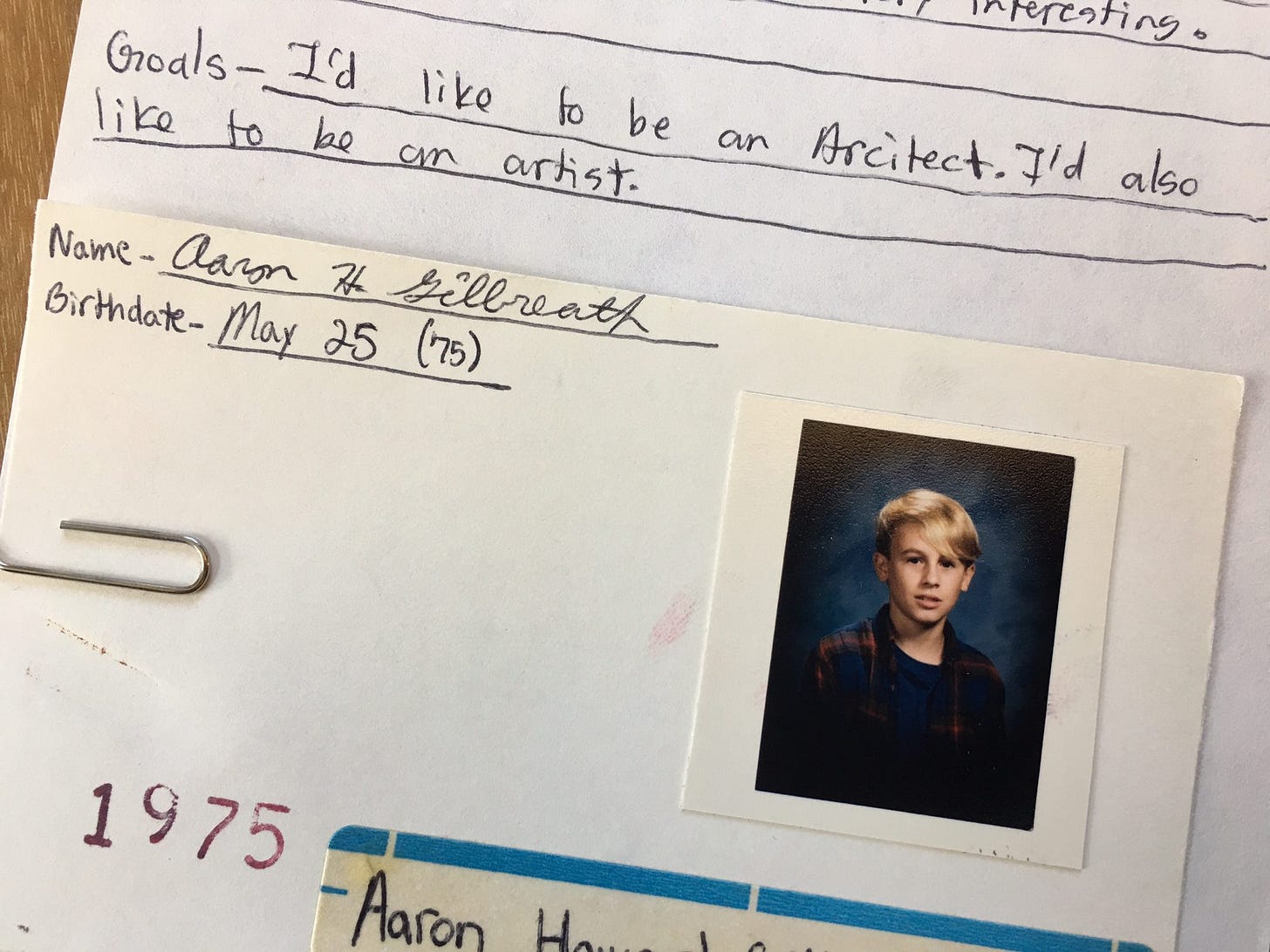

In seventh grade, a tight-knit group of female classmates had become obsessed with Depeche Mode. These girls sported their black DM concert tees in class. They chatted about the wonders of the Black Celebration album and longed for the band’s next Arizona performance. And they joked that they were married to their self-appointed DM “husbands.” Kristin wed herself to singer Dave Gahan, Nikki to songwriter Martin Gore, Kari to keyboardist Andy Fletcher. These girls were so cool to me. Their excitement was exciting, even though my skater friends and I teased them about it. As boys do, I quickly developed a crush on one of them, named Laura. “Never mind the divides of distance, age, space or time,” Laura wrote decades later in an essay about her fandom. “It had to be holy matrimony.” She’d married Alan Wilder. Curious what it was about these Brits that had them so enamored, I bought Music for the Masses. That album appeared on some of their shirts.

While spinning the LP alone in my room, I discovered a partial explanation: DM’s music was profoundly different. It had haunted melodies, inventive percussions, and it created a moody ambiance by layering orchestral synthesizers with field recordings that the band made by banging on metal and revving their car engine. DM struck me drunk, which was a sensation as mysterious and domineering at age 13 as my crush.

I’d started skateboarding in fifth grade, in 1985, so I went from listening to Thriller and INXS to listening to underground music throughout middle school, from Violent Femmes to Agent Orange to Black Flag. When I grew up in Phoenix, that stuff was still sub-cultural. For some reason some people considered it subversive. To me it was just the music we skateboarders listened to, which wasn’t the hair metal or pop or goth music that other kids listened to.

When I started high school in 1989, my favorite bands were Depeche Mode and The Cult. That changed quickly after friends introduced me to Jane’s Addiction, The Wonder Stuff, and Mother Love Bone, and my whole world started to revolve around rock ‘n’ roll. But first, I was all about DM.

DM’s career has spanned four decades. When I found them, they played huge concert venues all over the world but were between records. They’d released the hugely successful Music for the Masses in 1987 and would release 101 in 1989. They kept getting bigger and bigger, just as alternative music was starting to go mainstream.

It’s hard to believe, but at the same time, hair metal ruled the airwaves. Poison, Whitesnake, Foreigner, Skid Row, just the absolute worst fucking music played on MTV and the radio everywhere you went. Punk rock was hanging on, but the goth subculture and listeners of college radio who constituted a lot of DM’s fanbase—people who often liked The Cure, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Jesus and Mary Chain, and Sugarcubes, too—were also the ones carrying the torch of the subculture, the ones who didn’t just listen to whatever mainstream America force-fed you. As a skater, I was all about subverting mainstream America. My friends and I wore Van’s and flannels. We skateboarded through malls just to piss off security guards, sawed shotgun shells in half in order to light their contents, and I sang the Violent Femmes’ “You can just kiss off into the air” as a kind of anthem. Even though I didn’t dress like a goth, I shared their fierce independence.

Later in life I’ve come to appreciate certain things about metal, but as a kid, I loathed it. And unfortunately, metal ruled my Phoenix. Kids with feathered hair and Sacred Reich shirts worked the deli at Los Arcos Mall. Dudes with brown suede moccasin boots played video games next to me at the arcade and kept quarters in their tasseled jackets. They wore torn jeans in the heat of summer and did not, yet, skate the same concrete flood control banks that we skated. Few even showed up at our skate spot, called The Wedge. A border fence of prepubescent mustache hair divided us, and each side liked it that way. How did so many teen metalheads have mustaches? I barely had leg hair.

Walking the halls of my middle school behind hunchback boys with shaggy bangs, I got to study the graphics on their metal shirts. One featured a skeleton with chains dangling from his ears. The skeleton leaned against a for-sale sign below the caption “Peace sells... but who’s buying?” Um, I thought, me? I liked peace. Except for the skeletons on my Powell Peralta skate t-shirts, gore didn’t speak to me. As a kid, I drew all the time and read violent comics, but drawings either seemed cool or cheesy, and metal ones were cheesy.

My skater classmate Greg, who also kinda grew a mustache, wore a bright yellow Cramps t-shirt to school, featuring a ghoul with a pompadour and the caption “Bad music for bad people.” I loved it before I even heard the band. But the cartoon worked because Greg was genuinely subversive. One day in the lunch line Greg said, “Here, hold this,” and pulled a bag of weed out from the front of his shorts. I’d never seen weed before. I didn’t have time to look at it. He told me to shove it in my pocket and then he bounded off somewhere. This guy once told me that his mom bought him condoms. We were in sixth grade. When he got back in line, I handed him the weed, and we scanned whatever English muffin pizza discs or greasy mac ‘n’ cheese awaited us under the heat lamps. Was he a bad person who liked bad music? Should I be more bad? Compared to Greg’s true rebellion, the drawings on those metal t-shirts seemed like empty bluffs, and so did I. I was so soft on the inside, and I couldn’t find a way to like it that way yet. So I talked shit to people. I played aggressive music. And I cloaked myself in skate shirts covered with monsters and skulls as a defense.

I never related to metal’s aesthetics or canned lyrics. First, the names were awful: Ratt, Twisted Sister, Megadeth. Second, its dick-obsessed sexist machismo put me off. “Cum On Feel the Noise” and “Girls, Girls, Girls” were lame and offensive. Sure, I had discovered the wonders of human genitalia by then, but I didn’t need to wag it in anyone’s face or wear a cod piece to highlight its existence. I had a lot of female friends, and they were not just “girls, girls, girls.” They were my sisters. Third, metal had horrible album covers. They looked cheap, like a middle schooler had painted them. Quiet Riot had a dude in a straightjacket on one album cover. Iron Maiden had their monster character Eddie holding a tattered English flag on a battlefield. Ozzy’s Bark at the Moon only worked as parody, as Beck Hansen later proved. Graveyards and werewolves weren’t motifs that appealed to me, so I never went through an Ozzy or Metallica phase. Black Sabbath sounded bad ass, but solo Ozzy was always the butt of my jokes. I couldn’t respect any band like Iron Maiden who needed to perform with huge monster statues on stage. Your music was either scary, or it wasn’t. Even Danzig’s lyrics and skull iconography seemed corny, and that band was supposed to be evil punk. It’s the same reason so many punk albums put me off. Album covers meant something. They functioned as an album’s first note. The iconic cover of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures album cover was on t-shirts everywhere I looked, and its bleak minimalism piqued my interest. It said nothing but suggested everything. Suggestion seemed scary. Like the obelisks in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Joy Division’s sonogram just lay there, cold and unfeeling, its inhumanity facing you. Metal said too much and it was all bluster. I liked the clean, almost Danish designs on my classmates’ Depeche Mode shirts: megaphones; black, red and cream colors; artfully suggestive.

By the time the girls introduced me to DM, I was tired of Suicidal Tendencies, bored with Black Flag. I didn’t like any of Violent Femmes’ new music, so for me it was all “Add It Up” and “Kiss Off,” which were great. Saying this will work against me, but I thought the Sex Pistols were stupid. Black Flag struck me as too simple musically. I was supposed to like them and Dead Kennedys, but I didn’t like Jello Biafra’s singing as much as I liked East Bay Ray’s guitar. Saying I liked Suicidal Tendencies made me feel tough and rebellious; privately, I only liked two songs, especially “Institutionalized” where they sing: “I’m not crazy! Institution. You’re the one who’s crazy!” To teens, the adult world always seems crazy, so that’s a timeless anthem.

Punk culture provided a home for many wayward kids. It was a safe haven where they could build their own world. And punk music got so many people to pick up instruments, because it proved that anyone could write their own songs, often with three chords. The Sex Pistols inspired so many young artists, including Fugazi’s Ian MacCaye. Seeing Naked Raygun play a small Chicago club transformed the teenage Dave Grohl into a drummer. “[I]t just turned me,” he told NPR. “Like, that was it.” That’s huge. For me, the costume never fit. Despite my punk ass attitude and reputation for mischief, I never dressed punk. I only embraced its spirit. It took years for me to discover the countless kickass punk bands that I’d missed as a kid: Bad Brains, The Zeros, The Pagans, The Plugz, X. But visually, as a kid, I was a beach-brained desert rat obsessed with flannels, Van’s, and striped tees whose bedroom became a strange mix of surf iconography and DM, like beach goth before anyone coined the term. Musically, I preferred the Duke Ellington my dad played me, especially the eerie, blue sounding early Harlem stuff in minor keys like “The Mooche” and “Black and Tan Fantasy.” That sounded authentic. Punk teens made punk rock feel put on. Even punk bans acted too angry on stage for me to believe it. I still loved my old INXS and Duran Duran, and I loved dark catchy melodies I could sing to, or better yet, cry to, which is why I loved The Cure’s slow songs. My middle school musical life had left a vacuum that DM filled upon first listening. As they sang: “I’m taking a ride with my best friend / I hope he never lets me down again.” That’s how they became for me: the band in the driver’s seat, leading me from eighth grade toward freshman year.

While my friends and I watched movies and blew things up, Laura and Kristin spent Friday and Saturday nights on a pull-out couch studying DM, in Laura’s words, “with a rigor that did not extend to our actual studies. We learned the geography of Basildon, England, the working-class suburb where a young Dave had met Martin Gore, the sensitive schoolboy in whom a thousand pop hooks were incubating beneath the dreary British sky. When we read in Teen Beat that Dave liked mushroom pizza, we vowed never to eat anything else again. We ate mushroom pizza and watched MTV and when Depeche Mode came on, we wiggled.”

Within a couple months of listening I had joined their ranks of obsessed fandom. I bought every studio album, working my way backward through the DM catalogue from Music for the Masses to Speak and Spell. Although I never wore much black as a kid, DM’s album Black Celebration remains one of my favorite albums of all time, and the band in that era one of the most iconic.

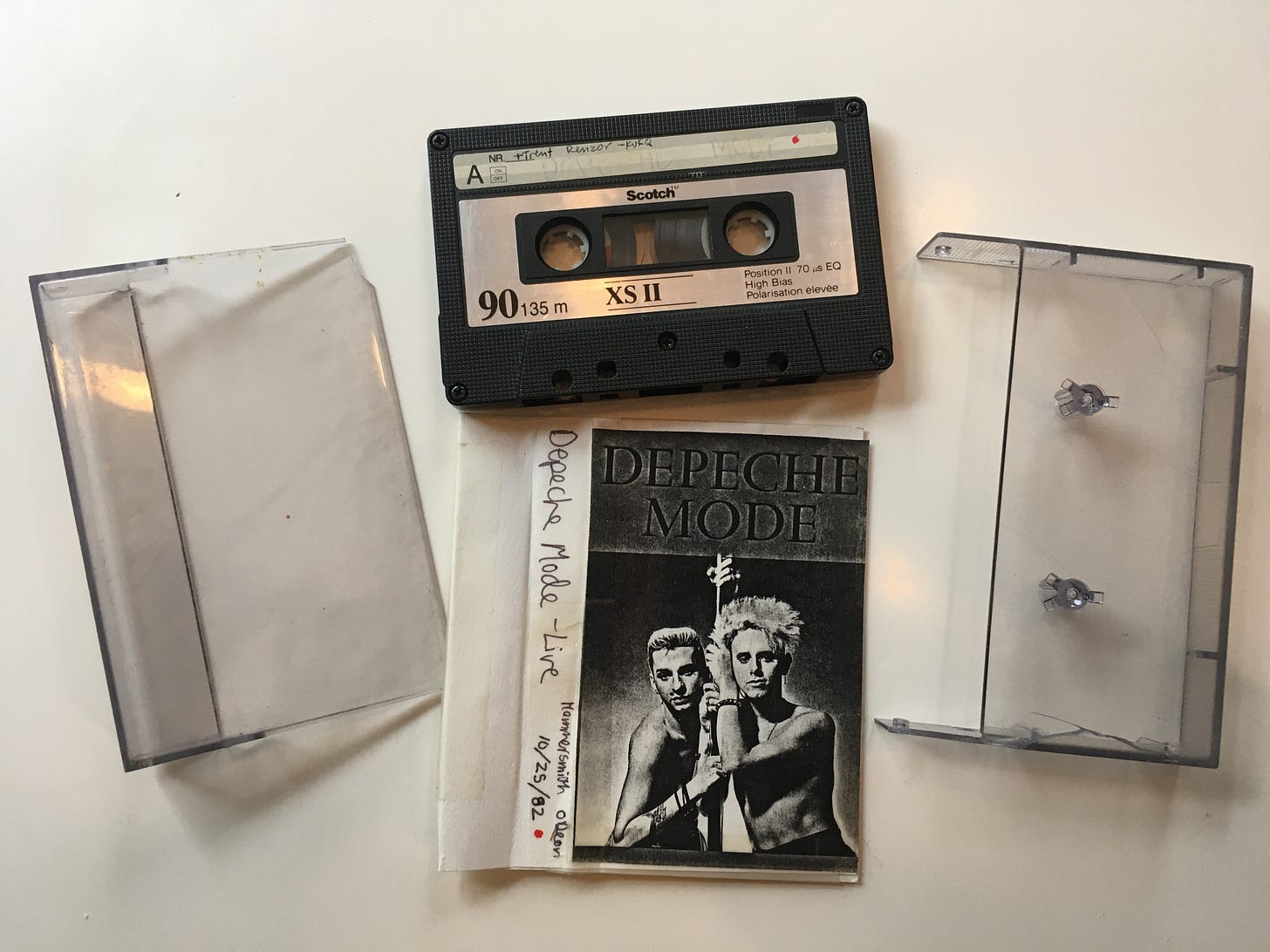

I spent weekends riding bikes with friends to record stores, searching for over-priced imports featuring multiple dance-remixes of single songs with names like the “Renegade Soundwave Afghan Surgery Mix.” I coated my bedroom with posters, painted the letters “DM” on the wall beside my bed, mail-ordered concert tees from tours I was too young to attend, and I wrote letters to fans in England who sent me cassettes of early ’80s live recordings from places like London’s Bridgehouse Club that contained unreleased songs like “Price of Love,” “Television Set,” and “Reason Man”—then considered holy grails in the fan community.

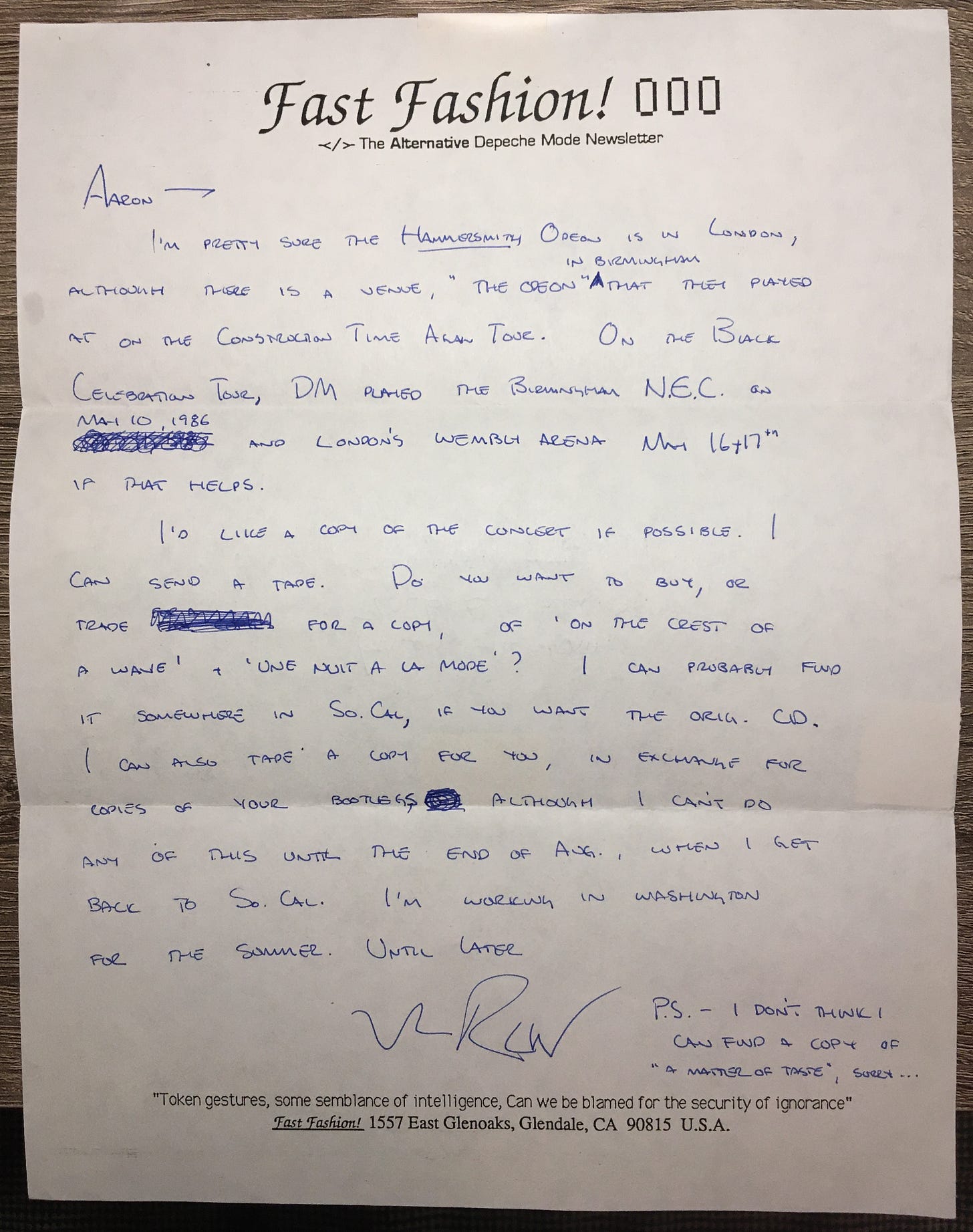

I even traded letters with the fan who ran Fast Fashion! The Alternative Depeche Mode Newsletter. She wrote in stylish all-caps. She had an out-of-state job. How old was she? She was so kind:

The live version of “Photographic” from their bootlegged 1984 Hamburg concert struck me as one of the most stirring songs I’d heard. First a faint electronic twittering moved back and forth between speakers. The deep thump of the base drum hit—doomp, doomp, doomp, doomp—before Dave sang: “A white house, a white room, the program of today.” I didn’t know what the hell he was singing about, but I sang with him. It wasn’t the lyrics that moved me so much as the layers of sound and harmonies where Martin lays his high voice atop Dave’s deep one. “And looking to the day,” they sing, “I mesmerize the light.” From then on, bootlegs were my thing.

Underneath the synthetic sounds, Depeche Mode’s music contained a depth of humanity that hit me hard, a darkness and mood that punk rock lacked. While the music became my master, I secretly hoped Laura’s and my shared interest would forge a friendship that might lead to friendly phone calls, a date, maybe some kissing to “Strangelove” underneath my postered walls. Instead, we graduated from middle school having mostly talked about the band. She never gave me her phone number, and I was too shy to ask.

When I started at an all-boys Jesuit high school in 1989, my fandom created a problem. Not an actual physical problem. I doubt anyone would have threatened me. The problem was internal. The cruel homophobia endemic to boys this age made me self-conscious about my love of this effete electronic band. Radio was homophobic. Kids played a game called “smear the queer” on the playground. People called certain music “sissy music,” and worse. Among young homophobes, DM seemed like a group of gay men playing music for other gay men, and most young American boys seemed like homophobes to me, with their shit-talk and name-calling and overly aggressive, ear-boxing horseplay. After all, I enjoyed using shotgun gunpowder to blow things up. The switch from middle to high school looms large in kids’ minds, and music, as much as friendships, can make the transition easier or difficult.

My all-boys Jesuit high school had a reputation for providing a solid education, which is why I asked my parents to attend, but being same-sex made it the target of homophobia. The joke around town was: “Why doesn’t Brophy have stairs? Because fairies can fly.” Boys actually said that to me. Starting an all-boys school as a tiny unthreatening person, I didn’t want to attract attention or give upper classmen reason to harass me. Granted, the entire student body only consisted of some 1029 students, so around 243 in my class—but I feared being ostracized. I loved these soft British men and their androgynous leather-wearing personas, but I hadn’t reached the age where I could stand up for all that entailed.

Among the geeks and fellow zitty teens, my high school had a strong jock culture. Many of Brophy College Preparatory’s upper echelons were football player-types. Kids drove Ford Broncos because the school’s mascot was a bronco. Many worshipped hair bands like Van Halen. Hard-rocking, hard-living, best played at high volume, Halen seemed to power my classmates’ budding masculinity like sunlight to a sapling pine. Eddie Van Halen churned out blazing guitar solos shirtless and scored what young guys would call a hot actress wife. Michael Anthony played a bass shaped like a Jack Daniels bottle. David Lee Roth sang about how bad he had it (“so bad”) for a foxy teacher. In addition to the licks and high head-banging quotient, songs like “Jamie’s Cryin’” and “Ain’t Talkin’ ’bout Love” oozed the popular American conception of sexuality, offering such tawdry, sing-along lines as “He wanted her tonight, and it was now or never” and “My love is rotten to the core.” Even though the bulge in Roth’s tights loomed too large for my taste, guys at school were picking up what Halen was laying down. The message, in adolescent terms, was: machismo is in your face, get used to it. It didn’t matter that a longhaired man in tights delivered it or that most hair bands wore more makeup than their female fans did. My sporty classmates passed tins of Copenhagen in class. They left spent brown wads in the drinking fountains so that when you bent over to get some water, a nasty wad greeted you half the time. Others, like class alpha male Darren, called Jews like me kikes and fanned their farts to nearby students. I once watched Darren unbend a paper clip in history and use it to pick his nose. There, in the front row of a U-shaped seating arrangement, he studied the contraption and the excavated junk on its tip, proud of his ingenuity. He stared at his tool like a chimp, as if he’d invented the nasal equivalent of a toothbrush with one of those curved necks. I shouldn’t have cared what these lunkheads thought, but I did, because that’s adolescence for you, so I took my fandom and closet full of DM shirts underground. Only my closest friends knew.

You have to remember: The so-called Alternative Era that we associate with the early ’90s began during America’s metal era. That’s what Nirvana’s sudden success helped destroy: commercial metal. Nirvana was a kind of rock janitor, clearing the old crap from the airwaves so the new alternative crap could take over. My high school experience started during the reign of Motley Crüe and Aerosmith, so it felt good to subvert that in any way, but also scary.

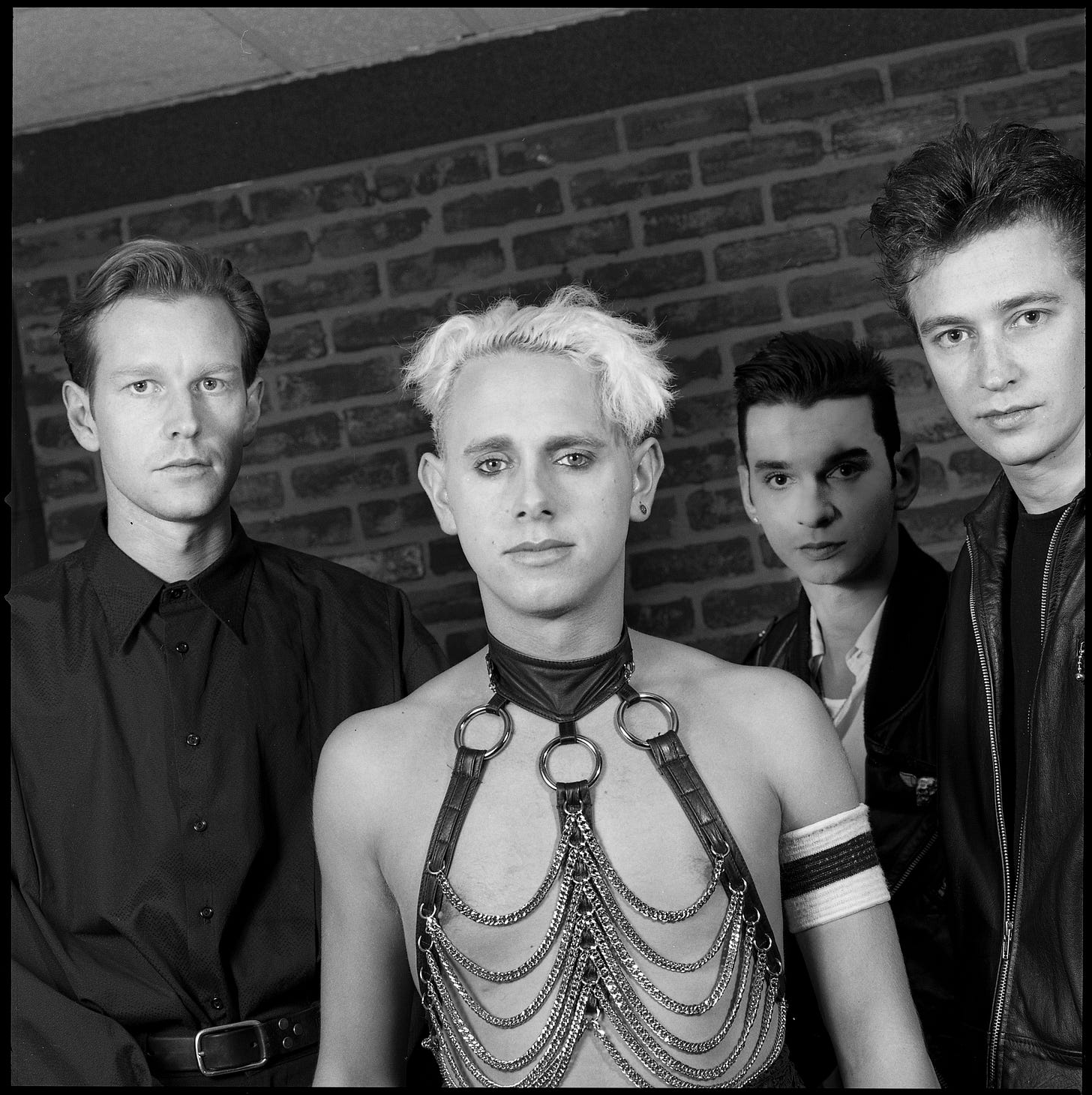

In the mid-80s, before and around Black Celebration, DM developed a sharper, more chic urban image: leather jackets with zip-up wrists, Army-Navy flak jackets, thick motorcycle boots, and black turtle necks with a zipper up the front. Everything from this period seemed webbed with zippers. To me, mid- to late-80s DM looked stylish as hell. If I hadn’t already committed myself to Van’s and flannels, I may have dressed that way, too. But American culture equated debauchery with manliness and godliness, and I’d internalized that Zeppelin-style rock heteronormativity.

Before underground music taught me about gender, originality, creativity, and leading a life my own way, all I had was late-80s pop culture to contend with. Looking back, it’s clear that, like a shrimp, I had been absorbing the toxins that pollute America’s cultural waters: the idea that debauchery and sexual excess were the same as manliness.

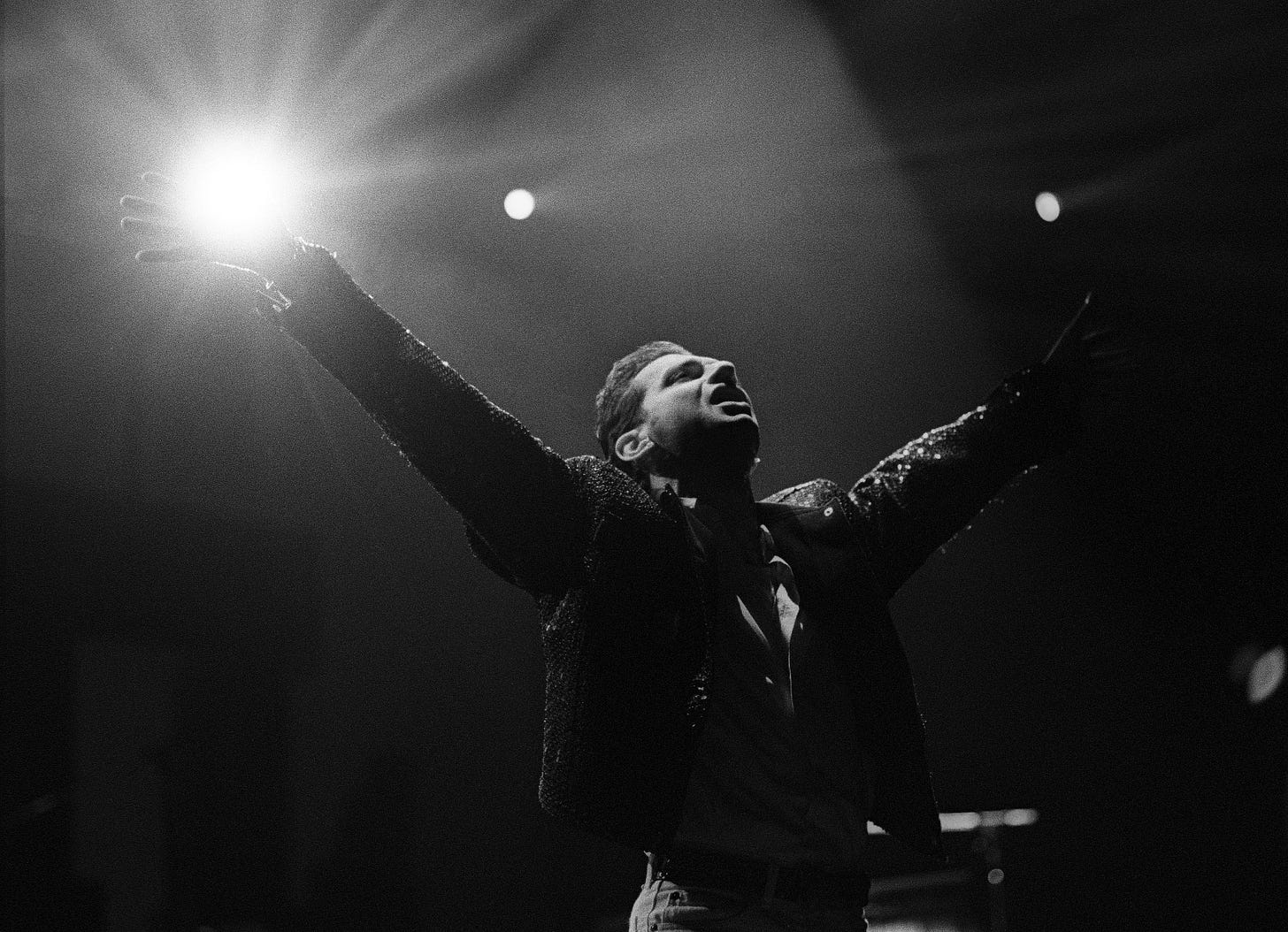

When DM released their masterpiece Violator in 1990, it seemed half the guys my age were banging their heads to Mötley Crüe’s “Dr. Feelgood” and Aerosmith’s “Love in an Elevator.” The general consensus was that these were real rock stars. They didn’t bang their heads during a synthesizer solo. Even though Martin had started playing more guitar with Black Celebration, no one was going to give him credit for it. DM played their songs on keyboards, not Gibson Flying-Vs, and mostly used a drum track instead of a live drummer. To macho rock America, they were essentially pasty computer geeks who’d ended up on the concert stage rather than behind it working the lights. On the surface, Depeche Mode seemed an unlikely success. Their stage presence didn’t square with their ability to fill concert stadiums: three guys standing behind keyboards while the singer, Dave Gahan, danced hard enough to make up for the others and engage the crowd. Dave had to be extra charismatic to create energy that matched the music’s rhythms. This wasn’t a guitar band jumping off the drum riser. Yet the music was so powerful that it worked.

Because here’s what we know: Manliness is a worthless concept. So is machismo.

Neal Preston’s 1975 photo of Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page swilling from a bottle of Jack Daniels backstage in Indianapolis captures the proud hedonism many non-musicians envy about the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle.

Mötley Crüe were as famous for their backstage womanizing and drug consumption as for their music. The lyrics on their 1987 album Girls, Girls, Girls celebrate the band’s dumb passions and experiences: whiskey, sex, motorcycles, strip clubs, drugs, and rowdiness. Girls is one of the Crüe’s two most popular albums, its namesake song one of metal’s most anthemic. As if to legitimize such recklessness, their 1989 song “Kickstart My Heart” was nominated for a Grammy. It was inspired by the two adrenalin shots that revived bassist Nikki Sixx after his near-fatal heroin overdose.

And Guns ’N Roses’ lead guitarist Slash bore all the habits and accoutrements of what has to come to embody the so-called true rock ‘n’ roller: leather pants, long hair, dark sunglasses, soloing with a lit cigarette in his mouth. The name of GNR’s first and best album, Appetite for Destruction, so precisely sums up rock culture’s macho value system it could have been titled Appetite for Self-Destruction.

The idea that these guys were supposedly “real men” is laughable. Acting tough only got some of rock’s biggest bad asses diseases and early death. But as kids, boys are constantly told to check their pants to clarify if they’re men or not.

After drinking 40 measures of vodka during a day of band practice, Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham died at age 32 from pulmonary edema: fatal water-logging of the lungs caused by inhaling his own vomit. Guns N’ Roses’ old drummer Steven Adler still struggled with drug addiction 18 years after the band fired him for substance abuse. You can watch the tragic drama on VH1’s TV show Celebrity Rehab Presents Sober House. It’s sad. His lip sags after a potent speedball injection caused a stroke in ’96. Before those adrenalin shots revived him, Mötley Crüe’s Nikki Sixx was medically dead for two minutes after his overdose. And Crüe lead singer Vince Neil killed his friend and passenger, Hanoi Rocks drummer Nicholas “Razzle” Dingley, in a head-on collision in 1984. They were returning from the liquor store.

I say this as someone who actually likes a few of those Appetite for Destruction songs.

What I loved about DM was how they could be simultaneously catchy and dark, sexy and dorky. They wrote wonderful pop melodies that had simple choruses you could sing along to. And yet the melodies were brooding, sometimes sinister, with unusual harmonies in unusual keys. The band was more interesting sonically and more challenging musically than the brainless punk records that I, as a skateboaring male, was supposed to like. Black Flag’s “TV Party” was good teen fun, and their album My War is hugely influential, but it couldn’t stand up next to “Question of Time.” For me, lyrics were always secondary to music. Songs rarely spoke to me through language. I loved melodies, rhythms, and atmosphere first. But when you listened to DM’s lyrics, you heard thoughtful, deep lyrics.

DM sang about literal and figurative bondage, about sexuality, friendship, drugs. They wrote political songs about human rights (“People Are People”) and environmentalism (“The Landscape Is Changing”). Like all good art, DM lyrics leave room for interpretation. In “Strangelove” Dave Gahan sings: “Strange highs and strange lows. Strangelove, that’s how our love goes. …Pain. Will you return it?” In “Master and Servant” he sings about a new game that’s a lot like life, a “play between the sheets. With you on top and me underneath, forget all about equality.” In 1989, that only fed rumors of the band’s sexual orientation. In my adulthood, I liked how their intentional ambiguity tested gender boundaries and challenged listeners to think beyond categories. It was sexy, and I was awakening sexually. Dave had a sexually charged way about him, with the bulge in his crotch and those tight jeans. Even if you didn’t want to fuck him, he made me think about fucking, and I liked that. I was a teen, figuring out my body and sexuality. I didn’t understand much, but I took my cues from musicians, and I loved looking at these ones.

I loved how un-macho they were, how they wore make up and tried on different identities. They didn’t need to be what you wanted them to be, and that spoke to me. I couldn’t say it out loud yet, but I had a deeply sensitive quality about me that needed someone non-conforming, creative, and poetic like Martin Gore to look up to. I’d read somewhere that sexuality sat on a spectrum. Young boys don’t like to hear that. The spectrum makes them uncomfortable. But some of us love that gray area, which is partly why we love Bowie and Prince and Queen. Their music moves you. Their identities encourage you. We like people who test categories and like pushing close-minded peoples’ boundaries. Depeche Mode did that but trapped me in a teenage contradiction: I liked their fluid identities, but I was insecure enough to care what people thought of me. Like most teenagers, I needed acceptance but wanted room to rebel.

Punk often rebelled against enemies, including parents, teachers, schools, Reaganomics, and a restrictive misguided society. But punk’s best part wasn’t the music for me initially. It was the idea of doing things yourself, of not waiting for institutions to structure your life or career for you, and creating your own identity instead. Interestingly, punk rock and DM shared that ethos and something else: Both spoke to alienated youth. DM’s black leathery look made it popular with goth kids, so people who felt misunderstood or marginalized gravitated to DM the way others gravitated to Misfits or The Cramps. But back then, DM came with a personal cost. Changes of identity always do when you’re young. In a sense, rejecting rock for synthesizers and punk rockers for computer programmers was a subservice move in itself, just like rejecting gender norms was as punk a move as a band could make back in the late-80s. That process would flip for me soon after entering high school, when I moved from synths back to guitar-bands. But Depeche Mode shaped everything I became after, and as a high school freshman, I had to navigate this first.

Brophy dress code required students wear collared shirts, so I concealed my DM tees beneath regulation button-ups during my freshman year. I invited only my closest friends into my bedroom shrine. I spoke of my bootleg LP collection to local record store clerks in the way a cigar connoisseur might speak of his pre-embargo Cubans. Unlike my idols, I was too timid to do anything but keep my fandom secret.

Looking at photos of myself from that time, it’s clear that, besides my dad and my granddad, Martin Gore was my biggest male influence during my freshman year. Dresses, nail polish, crotch straps, chains—if he liked it, he wore it. Martin lived and made art on his own terms, and thrived because of it. And by example, he welcomed his adoring fans do the same.

One night, secretly, I recreated Martin’s bondage straps in my bedroom. I never told anyone. I didn’t know where to buy bondage gear. Since I couldn’t find scraps of leather at home, and I couldn’t gather the courage to purchase some at a belt store, I snipped the rough canvas straps from my JanSport backpack. The straps were black like Martin’s, and of a similar width. They just weren’t long enough. I removed my shirt. With the ends resting on my belt the way Martin’s did in one poster, my straps only came as high as my nipples. So I cut more straps from an older, smaller backpack and stapled them together to create two long straps. These fit all the way over my shoulders. I stapled their ends to a black leather belt—one of the few nice belts my parents bought me for formal occasions—to form a janky, art school, rip-rap set of homemade bondage suspenders.

Staring at my reflection in my tiny TV, I turned side to side to measure my resemblance to Martin. I rotated the way the female friends did in dressing room mirrors they let me inside at the mall. My TV screen was small, my image dim and incomplete. And while it occurred to me to sneak into the nearby bathroom to use the large mirror, I couldn’t stand the thought of seeing myself so clearly. What was I doing? What did this mean? I liked it, but sometimes a kid isn’t ready to see their true nature revealed. Instead, I peeled the gear off and buried it in my bottom dresser drawer, shoving it under clothes I no longer wore.

That night, staring at my blurry reflection, I wanted to believe my attraction to Martin was strictly artistic: Wasn’t one side effect of worshiping art the tendency to mimic its creator? The same way you buy posters to remain in perpetual contact with the music, you put on concert tees to embody the makers? But to say I loved his music and not his mind and sweet face now seems simplistic. Thankfully, the line between fandom and affection, admiration and attraction, is blury. If not his appearance, then what was I drawn to? The person? The mystique of creativity, the magnetic charisma of the inspired, soft-spoken, confident mastermind of a band? All of it. He was DM’s main songwriter. To birth transcendent music seemed a power of the gods. But to stand up and say “This is who I am” was even more powerful.

When DM’s Violator tour came to Phoenix, my excited friends and I went. The local paper called them “synthesizer mopes.” Besides seeing the Pointer Sisters at the state fair with my parents, this was the biggest concert I’d ever attended. Of course my middle school DM friends were there, too, trying to meet their band husbands. “Aaron!” they said, “you made it!”

One of them, Laura, had recently pulled off the most incredible scam: In May, 1989, she’d impersonated a Spin magazine journalist and managed to get Depeche Mode’s Andy Fletcher to call her for what he thought was an interview. She was 13. This became teen lore worthy of a John Hughes movie, the kind of move that I hoped to have the courage and vision to execute myself one day, in any aspect of life.

Like me, Laura became a writer in college. Thankfully, she wrote a whole essay about her fandom:

I called every place listed in Depeche Mode liner notes—studios, manufacturers, distributors. I looked up engineers, producers, people thanked in the credits, some of whom were dead.

“Hello, I’m with Spin Magazine,” I said, again and again. “I’d like to interview Depeche Mode.”

Finally, miraculously, I found Tamsin Yee, director of publicity at Sire Records, Depeche Mode’s American record label. She wanted to know: My angle? The art? The spread?

“It’s about the band’s new movie,” I said. “There’ll be photographs.”

Tamsin did not ask for clips or references. Instead, she told me to expect a call from Andy Fletcher in three days. Management would be in touch, she said. I left strict instructions for my family to answer the phone as if they were in a busy office. My office. My mom, bless her, bought me a two-way telephone recorder. My dad helped me brainstorm questions.

I told you these girls were cool.

During the interview, Laura’s DM friends Kristin and Nikki were on the speakerphone in Laura’s dad’s office, supposedly on mute.

The phone rang at 11:03 am. Laura picked up. “Hi,” a voice said. “This is Andy Fletcher. Am I speaking to Laura Bond?”

She interviewed him for a while before she heard her giggling friends Nikki and Kristin yelled, “Andy! We love you!”

“What?” he asked. “What’s going on?”

We confessed everything. About the mushroom pizza and our war with Guns and Roses and our wedding plans.

“Andy!” Nikki said. “We put on your videos, and we act them out! Every single one!”

“We have fantasized about being your toilet paper!” Kristin shouted.

To his eternal credit, Andy Fletcher was a sport and a gentleman. “Which one’s married to Martin?” he asked. “Listen girls. Right now you love us. In two years you’ll be like, Depeche Who? What?”

“Never!” we cried.

Before we hung up, Andy said the interview was “better than the last one I did for Spin. The guy took us to Central Park and said, ‘What do you think of that tree?’ Well done, then.”

The next call was from Tamsin Yee, the publicist, who threatened my mother with a lawsuit unless I announced over the loudspeaker at school that I had made the whole story up. That there had been no phone call, no contact. My mother responded cooly that she couldn’t have been more proud.

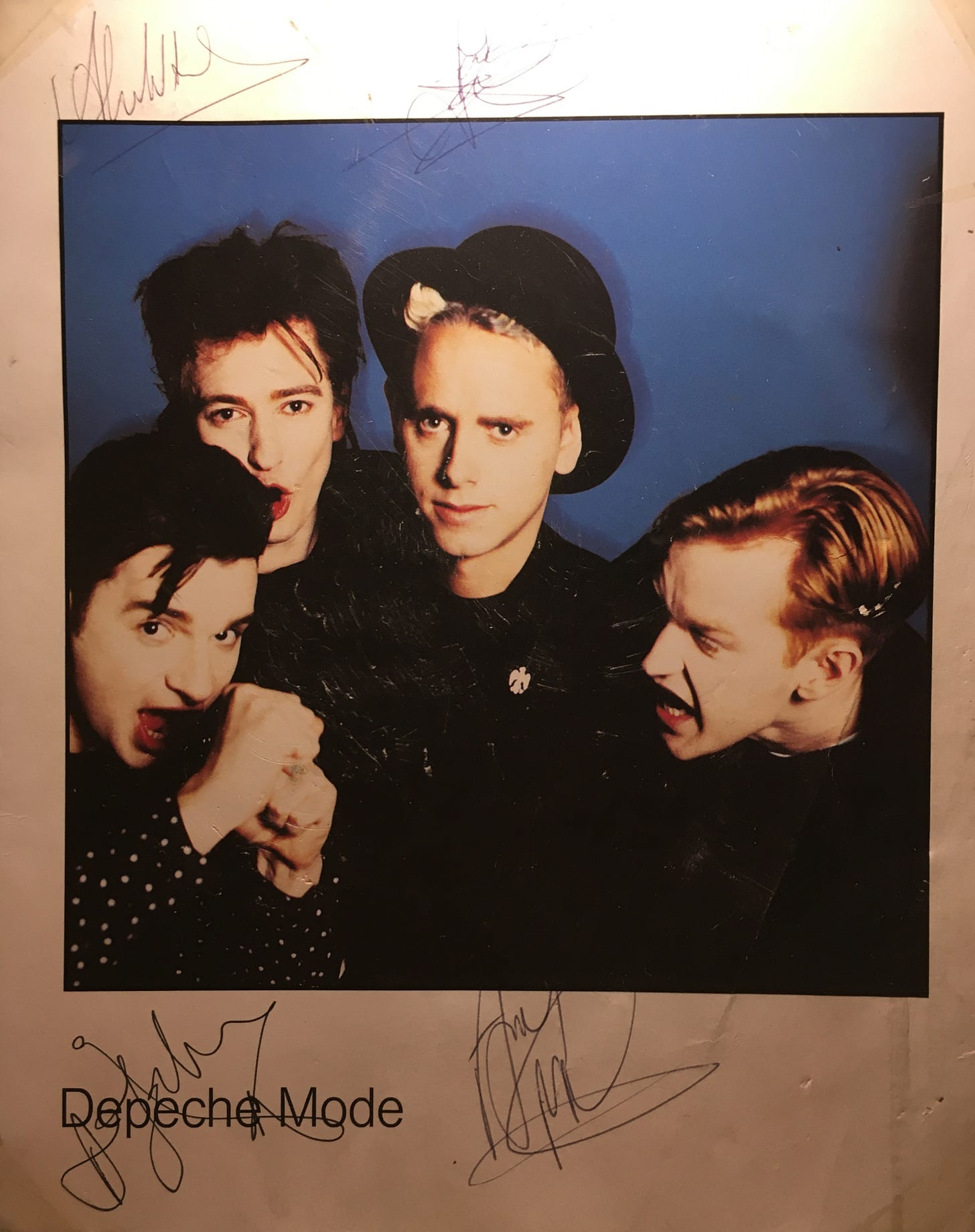

Anyone that crafty could lead me anywhere. At the Violator show, Laura’s crew led me and my friends around the back of Veterans Memorial Coliseum where, behind a cement security barrier set way up high above the rear loading area, we watched the band step out of a limousine. Dudes in black leather looked so out of place in the desert heat, and so cool. The girls were scheming how to get down there and meet them. Why not? They’d already fooled Andy once.

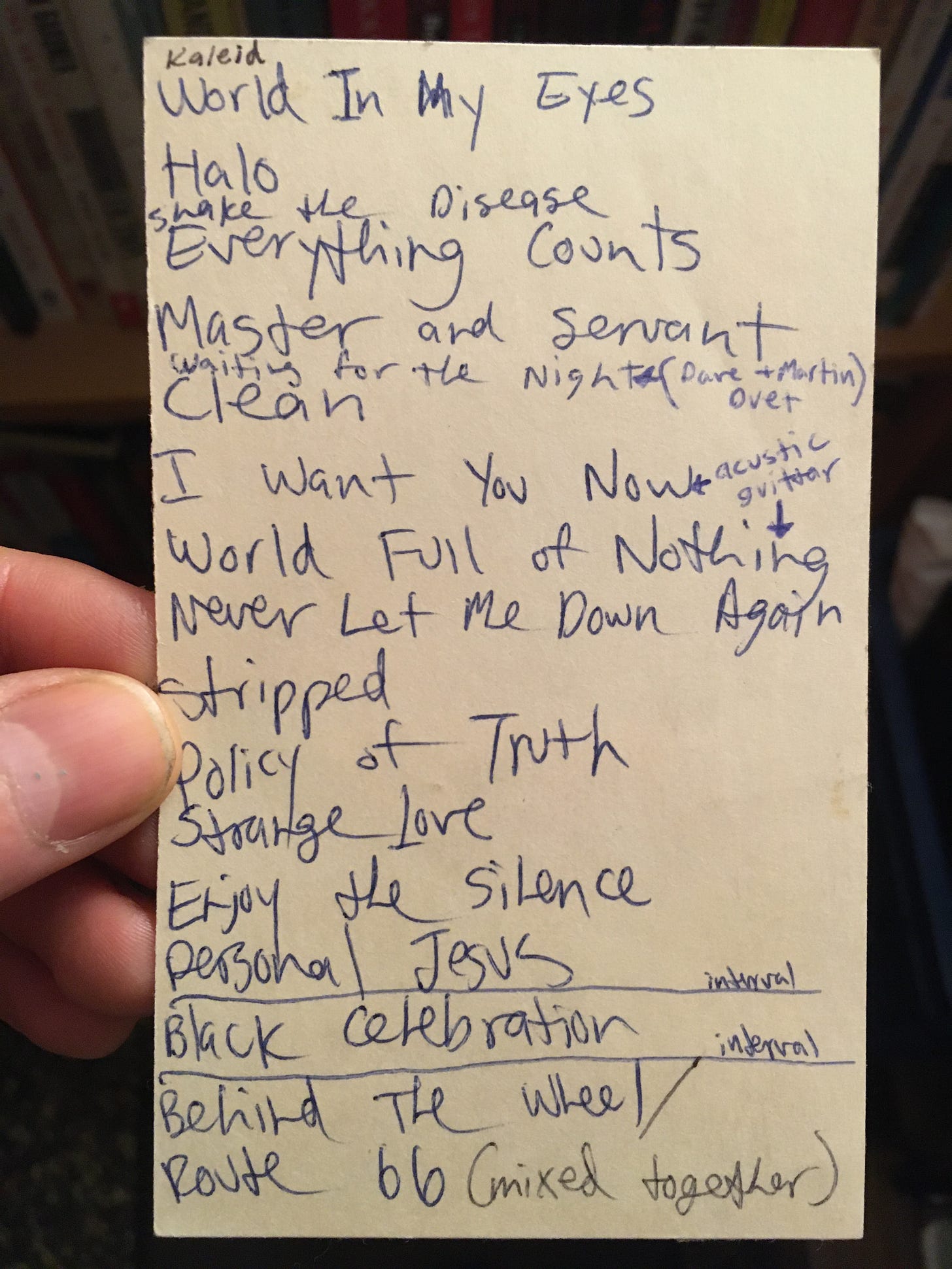

Because I couldn’t smuggle in a recorder to capture the music, I figured I could at least jot down the setlist on a scrap of paper inside the dark venue. Clearly I was obsessed with the spirit of live music.

Somehow Laura got the whole band to sign my DM press photo signed. I don’t know how. I’m still grateful, for the photo, but mostly for the music, and helping liberate me from caveman pop culture, which freed me to be me, after years of effort.