Every day after high school, I’d come home with Elliott Smith’s “Miss Misery” lyrics in my head: “I’ll fake it through the day with some help from Johnny Walker Red.” I’d walk into the house, which was empty. My mom was a bus driver, and my dad always worked at his studio. I’d go up the stairs, take a left into their bedroom, into what was at one point going to be a walk-in closet, and instead became a messy storage unit for my dad’s instruments and our family photos. There were two large windows that faced the woods. With all that dappled afternoon light brushing up and down the walls, it was my treehouse, a sanctuary.

This was where my dad kept his bottle of Johnny Walker. I’d started drinking long before I heard the song, but that was always at parties, bonfires, and in parked cars—always a social thing. When I heard the rhythmic words Johnny Walker Red I thought they sounded familiar, and I wanted to live in them.

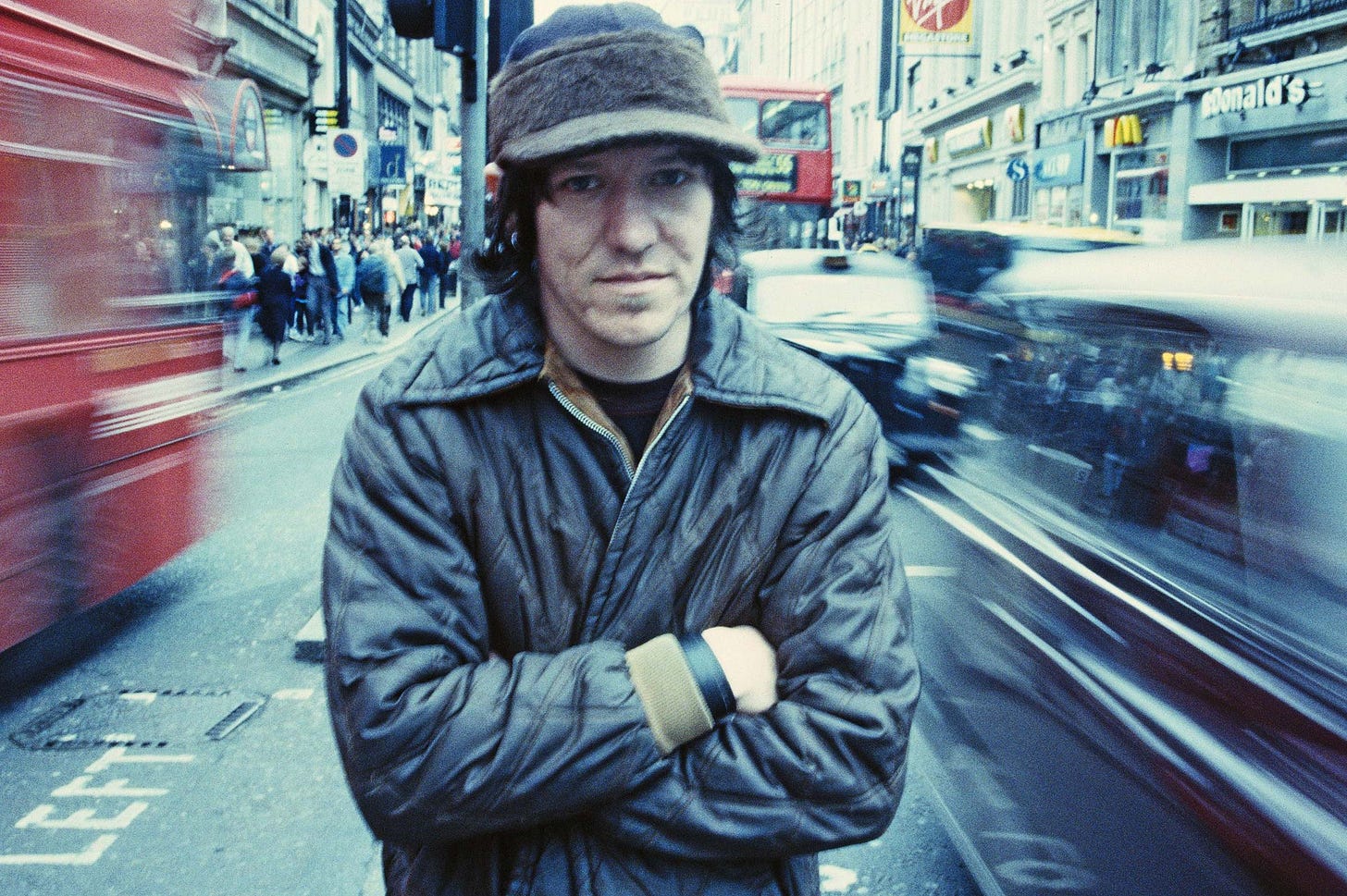

My best friend Simone played me “Miss Misery” in 2004, a few months after Smith died. She’d probably ripped it from file-sharing site Limewire. We were sitting in Digital Photography class. Our teacher had a black mustache and bald head, it was spring, and our computers were those bulbous Macs. They faced the windows. The classroom lights were off, so we could better color-correct our stupid snapshots of rusted train tracks and our own feet. After Simone played me the song, I listened to it once, twice, three times, endlessly, often just to hear the lonely first D-minor chord, the phrase, “I’ll fake it through the day,” in singsong, and the weary voice that sang it.

“To vanish into oblivion is easy to do.”

I was 16 and quickly discovering that the thing I was best at was drinking, so I’d quit trying to be good at field hockey, lacrosse, and tennis. I was the teammate with a big bottle in her bag for whatever was going down after practice. In my memory, I’d just done my first lines of cocaine the weekend before I heard the song. No one had warned me of the comedown, so I learned about it alone in my bedroom, where I couldn’t sleep and only had Dashboard Confessional to ease me. (Yes, there’s a Chris Carrabba-Elliott Smith pipeline.) I was 2, 3, and 5 a.m. tiptoeing into the kitchen to grab cans and cans of my mom’s Coors Light and then burying those cans in the woods behind my house. I’m sure they’re still there, a relic of little Miss Misery.

“Next door the TV’s flashing blue frames on the wall.”

I didn’t know I was a writer yet, but I couldn’t get this image out of my head. Of course, the TV was muted because the flashing blue frames were the focal point. I pictured a camera panning the exterior of an apartment building, floors up, looking in window after window, and stopping briefly on a man in a dirty white tank top, a beer can on the arm of his Lay-Z-Boy. I pictured Elliott playing his guitar next door for the oblivious man. Elliott was omniscient, a word I couldn’t have used back then because I never paid attention in English class, except when my teacher used an Incubus’ song to explain the concept of metaphor when really, she could have found one million better examples in any Elliott song. But she didn’t, because he was a druggie suicide, and we would never talk about someone like that.

My dad never noticed his Jonny Walker’s slow leak. If he did, he didn’t say anything. My parents never noticed the dip in the big milk jug of change they kept in his bedroom, which I’d pour out and pick through, taking all of the quarters to Coinstar. I’d have to fish out loose guitar picks from the little sorting tray.

“All I want to know is happiness for you and me.”

I spent lunch periods in the guidance counselor’s office, the only place I felt safe admitting that I’d begun to use heroin. “But I only ever d0 this much,” I’d tell her, pinching my fingers together. “Just to feel normal.” By now, I was a full-blown Elliott Smith fanatic—you know the type, message boards at all. I’d moved on to a new favorite song, “Happiness/The Gondola Man.” I knew his Either/Or, XO, and Figure 8 albums by heart.

I had general and social anxiety disorder and was unmedicated. The only thing that seemed to help was getting drunk enough to stop thinking so much. At school, I couldn’t do that without getting found out. But I could do thiiiiis much heroin and still act normal. No one but my guidance counselor ever explicitly talked to me about what might be behind my substance use. Most adults repeatedly stated that drugs were illegal and punishable by law and school rules. My counselor would let me sit in her office with my pb&j Uncrustable and can of Sprite and just go on and on. Eventually, she connected me with a therapist who would help me get sober. Then I’d relapse.

People often blame drugs for Elliott Smith’s death, but he was sober when he killed himself. It was not the drugs but the lack of them or a better substitute. There’s a great metaphor here, but it’s too heavy to find.

“What I used to be will pass away and then you’ll see.”

On my eighteenth birthday, I got my first tattoo: the word ‘happiness’ on the back of my neck. I’d pulled it from a Google image of a set list written in Elliott’s loopy handwriting. The placement was not at all meaningful, I just thought it looked cool. But at a party weeks later, some drunk guy said, “Happiness—it’s always right behind you, isn’t it?”

I will always remember hearing my first Elliott Smith song in that photography class, Smith’s close-in-the-ear sounding voice, and the instrumental dissonance that makes each song a celebration and a dirge. I’ll always remember how I felt—though, thankfully, I don’t ever have to feel that way again. At age 16, life was beginning to feel out of my control. Hearing Elliott sing about wanting and failing to escape his mind made my own escape methods feel a little less lonely. We’d both fake it through the day with some help from Johnny Walker. It was our secret, between artist and listener, like every great song.