Ephraim Lewis Was Summer Lightning

30 years ago, the alt-soul singer's brilliant LP bridged the gap between trip-hop and neo-soul, before he died way too young

English soul man Ephraim Lewis fell to his death from a fourth-floor balcony in his Los Angeles apartment building on March 18, 1994. Some called it murder. Others called it suicide. Whichever word was used it, always ended with Lewis’s lifeless body on the concrete. In my imagination I see him hovering like an angel, his piercing eyes taking in one last glimpse of the city where he’d recently moved in search of pop star success, only to end up like a chapter in Hollywood Babylon.

Two years before his untimely death, Lewis released the brilliant yet overlooked album Skin, one of the best soul albums of the 1990s. Lewis’s music blended American gospel/soul with Jamaican dub, Euro-electro textures, and lush vocals. Unlike the pulsating hyperness of the new jack swing sound popular with American producers Teddy Riley and LA & Babyface in 1992, Skin had more in common with the dreamy Bristol soul of Massive Attack’s critically acclaimed Blue Lines, which came out the year before. Skin could be thought of as proto to the musical eras of trip-hop and neo-soul that would soon come from idiosyncratic artists and innovators Tricky, and Portishead, as well as Joi, D’Angelo, and Erkyah Badu. Meanwhile, marketers at Lewis’s label, Elektra, compared his music to that of Seal, whose self-titled debut album was released in 1991.

Lewis was a wonderful singer/songwriter from Wolverhampton, England whose divine voice swirled perfectly with the dark soundscapes constructed by producers Kevin Bacon and Jonathan Quarmby. Though the duo would go on to make records throughout the ’90s for Des’ree, Eagle Eye Cherry, and Finley Quaye, Skin was their first major label project. Cultural critic Ernest Hardy, a former L.A. Weekly cultural critic, became a fan of Skin and was optimistic. “Skin came out during one of the many incredibly fertile periods of UK Black music artists,” Hardy said via email, “the best of whom draw on a host of influences while forging their own sound and aesthetic.”

In addition, reviews were strong. “Poised between retro and techno, the young man just lets his emotions fly,” Jon Young wrote in an August 1992 Spin review, “ranging gracefully from a sultry growl to a sweet falsetto, sometimes in the same breath.” More than two decades later, Skin still sounds fresh, fitting comfortably next to the alternative soul of FKA twigs and Frank Ocean. As Lewis himself said in 1992, he made "future-looking kind of music.”

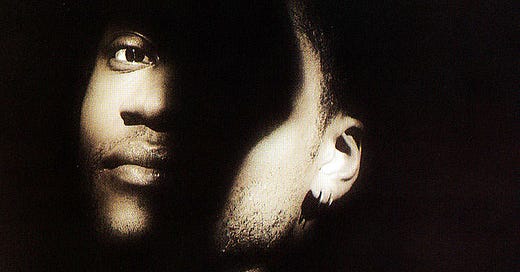

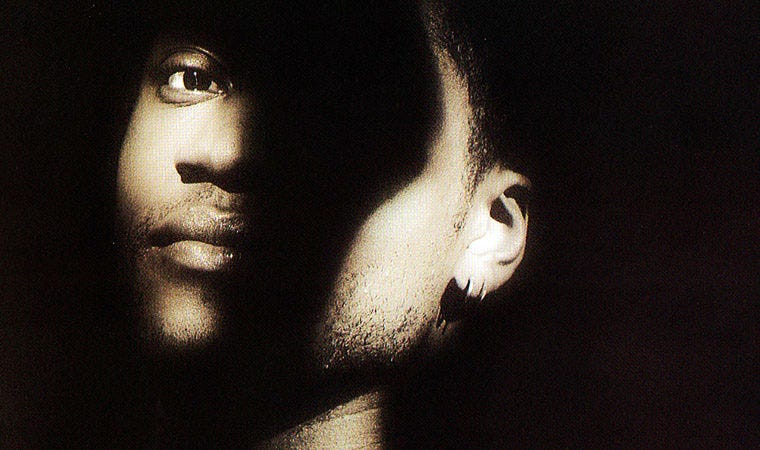

Staring at the album cover photograph shot by Kevin Westenberg, the image of Ephraim Lewis with his eyes closed and head bent as through in prayer spookily reminded me of Victorian corpse photos that showed deceased figures either propped upright or in their caskets. Lewis’s portrait had the look of death while most of the songs within were angst-ridden tales of lost or unrequited love. On the title track, Lewis sang his words as melodramatic as a Douglas Sirk movie. “Searching for a way out, of so much pain,” he moaned. “Skin” was followed by the equally moody “It Can’t Be Forever,” where Ephraim crooned, “So be brave, walk into fire. No one else can guide you.” With the heavy synths on “It Can’t Be Forever,” Lewis sounded as soulful as a postmodern Otis Redding. The “sleek melancholy” of Lewis’s lyrics and the electronic symphonics, combined with live instrumentation, was hypnotic.

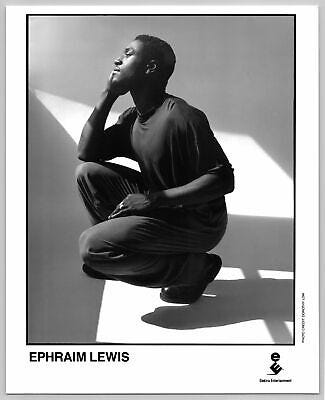

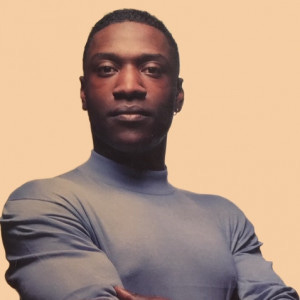

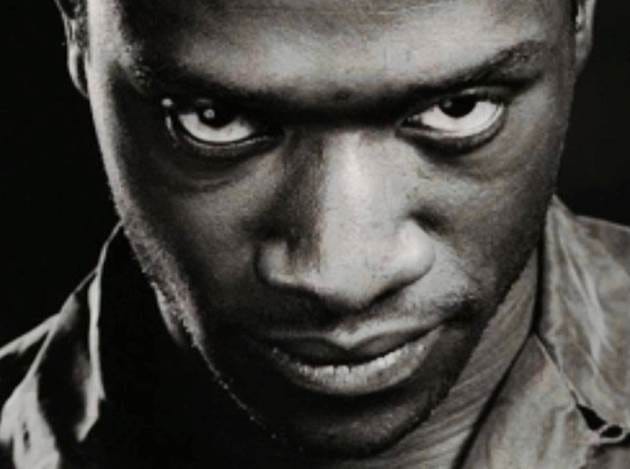

Meanwhile, as seen in various photos, including those shot by English photographer Paul Levitton for the Dutch magazine Nieuwe Revu, Lewis was dark-skinned and handsome as a fashion model. “When I saw him I was struck by his beautiful big eyes and amazing skin texture and bone structure,” Levitton recalls of their 1992 photo shoot in Amsterdam, “these are the things you look at as a photographer. I remember him as being very cool and relaxed. No BlaBlaBla, he just sat quietly and let me get on with my work.”

In a 1993 Vibe magazine article, writer Kevin Powell stated, “Each of Lewis’s songs is a sojourn into the trauma of loss and healing powers.” Powell, who was also a poet, acknowledged the beautiful strangeness of Lewis’s lyrics and got him to open-up about songcraft. “Writing is a learning process,” Lewis said. “When I wrote ‘Skin,’ I was feeling vulnerable emotionally. My mother and brother had died in the same year, and the song helped me to understand that insecure period when I was a teenager. I felt vulnerable, and I started doing what we all do, which is putting up a barrier between myself and others.”

Born on November 22, 1967, Lewis was the youngest of eight. Raised within the strict Wesleyan Holiness Church, he began singing and performing in the Lewis Five, with his guitar-playing father Jabez, who worked in the Goodyear Tire factory, and siblings. Forbidden to sing secular songs, the Lewis Five performed at churches throughout Lewis’ youth. That came to a screeching halt in 1984, when his mother died from a brain hemorrhage. Lewis was sixteen.

That same year, he left home and soon met Bacon & Quarmby. He began hanging out at their sound factory, Axis Studio. For the next few years, Lewis spent his days working menial jobs, including a stint at Kentucky Fried Chicken and nights perfecting his craft, recording demos and preparing for those big moments that were supposed to become his life. “Ephraim, he was very close to his mother, and his mother loved him,” his father Jabez was quoted in the Ubuntu Biography Project, “but, with all the children, when they grow up and begin to rebel, they don’t want to go to church, you see. That’s how it begins. I tell them all they don’t need to go out in the tough world to make money. They can make religious songs and get money from it. But they want the limelight.” Much of the information currently available on the Ubuntu Biography Project came from a currently defunct website operated by Paul Boakyn, who owns and operates Black Gay Blog. Though he reprinted the detailed story “The Brief Life and Tragic Death of Ephraim Lewis,” he wasn’t the writer of the piece.

“I found it as a press cutting online and used text recognition software to piece the essay together,” Boakye says. “I then contacted the author, whose name I forget now, and asked if I could repost the story with attribution on my website to keep the singer’s memory alive. The author agreed. I did all that because in 1996, I found a copy of Ephraim Lewis’s debut album on CD in a tiny record shop in Washington, DC. I loved it so much that I tried to discover other material by the singer and came across his tragic story by accident.”

Unfortunately, when Boakye deleted his website, he did not save the article. Still, twenty-four years after discovering Lewis’s music, Boakye remains a fan. “Ephraim’s greatest strength as a singer/songwriter was his ability to connect with audiences on an individual and very personal level,” Boakye says. “His sensitivity as an artist made it feel as if he was singing only to you. His music is both cognitive and perceptive at the same time, being more about head and heart than the groin, and that’s what drew me in.”

Producer Kevin Bacon, as also reported by Ubuntu Biography Project, said, “Ephraim had the qualities to be a massive star. This was somebody so brilliant at what he did he never thought about it. Most singers have tremendous egos based around their insecurity about their own singing. Ephraim didn’t have that kind of ego, because it never occurred to him there was anything he couldn’t do.”

Lewis’s lyrical warmth and hearty vocals were his initial connection with the label executives responsible for signing him in 1991. Elektra Records A&R Annie Roseberry heard Ephraim's demo and asked him to come in and sing for her. He selected “Summer Lightning” for the audition. The following year, Lewis told Blues & Soul journalist David Nathan, “Annie had a meeting with Bob Krasnow [Elektra’s head honcho] and mentioned to him that he had to hear my tape. I ended up doing a live audition on three songs—‘Drowning in Your Eyes,’ ‘Captured,’ and ‘It Can't Be Forever’—and I guess he liked what he heard.”

Then, as now, newly signed Black artists usually weren’t the label’s priority, and these artists’ budgets were often lower than the pop departments. However, that wasn’t the case with Ephraim Lewis, as producer Bacon told The Mail on Sunday in 1995. “We’d imagined it as a small-scale album from a new artist, the first step on Ephraim’s career ladder. Instead, when Bob Krasnow heard it, he went berserk about it and put millions of dollars into promotion to make it happen.”

Former Elektra Records publicist Lisa Jefferson, who worked in the company’s Los Angeles office, was Lewis’ West Coast press agent. “The white executives embraced him,” Jefferson says over the phone. “There was a big push behind him.” That “push” included splashy album release parties in California and New York, arty videos for the singles “Drowning in Your Eyes” and “It Can’t Be Forever,” and a booking on The Late Show with David Letterman, where Lewis performed “Summer Lightning”. Jefferson even hired journalist David Nathan to write Lewis’s press bio. The interview was done at what Nathan described as the “ultra-plus, spanking new” Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills. The writer depicted Lewis as being “unfazed” and “unaffected.”

Later in the story, Nathan wrote that in Lewis’s early years, he listened to gospel music and the sounds of Marvin Gaye and Nat King Cole, “the first two voices that inspired me,” Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield and Joni Mitchell. Like Prince, who also cited Mitchell as an inspiration, Ephraim’s lyrics were often spiritual, surreal, haunting, and dreamy.

“I’d say ‘Mortal Seed’ is about a difficult period of my life,” Lewis explained. “My girlfriend had gone through an abortion, and that wasn’t easy to deal with. Then, ‘Rules for Life’ and ‘It Can’t Be Forever’ are really songs I wrote out of observation. ‘Rules’ is about how people let things stop them from their goals and dreams in life, how life isn’t always just black and white.”

Nathan, who is today the founder of soulmusic.com, remembers that interview well. “Ephraim seemed a little awestruck by the way he was being given so much attention by Elektra,” Nathan says via email. “It was a whole new world and experience for him. Not in the least arrogant, but more, if anything, a little understated about his music.”

During that Skin promotional period, Nathan also saw Lewis perform at Catalina Bar & Grill in Hollywood. “What is most vivid was his gentle stage presence. He seemed comfortable and very natural onstage. No gimmicks, just a gentle soulful quality. There was something spiritual about his performance and his gentle manner that captivated the audience. His fluid falsetto and the sensual smoothness in his vocal style were very compelling.

“To me, all the songs on the album are about opening up to the creative forces in life,” Lewis said in 1992, “about spirituality—coming together as people, regardless of colour, age, upbringing or financial status. I’d say my music is subtly deep; it has an ethereal quality to it.”

Lewis’ music followed in a tradition of Black British artists who drew from their own experiences growing up as offspring of Afro-Caribbean immigrants in the UK, exposed to the more ‘tolerant’ approach in Britain to interracial friendships and relationships. These artists meshed the influence of US soul music with their own unique approach. I was reminded of pioneers like Junior (Giscombe), Loose Ends, and Imagination, who helped create that hybrid of UK/US Black music.

Picking Up Rocks blogger Hope Silverman, who was working at the CBGB’s Record Shop in 1992, attended Lewis’s New York City party for retailers, where she met the singer. “Ephraim had a presence, seemed infinitely cooler and more attractive than everyone in the room,” Siverman says. “He just had that innate magnetism. He was wearing all black, a tight turtleneck, and definitely looked fit. His voice was deep. It was a little loud in the room, because they were playing his album in the background, and so we had to lean in to talk to each other. I absolutely asked him if he was going to be touring, and he said yes. It was definitely being planned, and soon, and he was excited to get out there.”

Although Lewis never toured, the performance footage from his July 16, 1992 appearance on Letterman was great. Lewis appeared to be slightly nervous during the first song, “It Can’t Be Forever,” but, by the time he performed the second tune, “Summer Lightning,” it was as though he had angels guiding him through the hand gestures, stylish vocals, and a dramatic conclusion that damn near makes me cry.

“There was such an incredible smoothness to his voice,” Ernest Hardy says. “It conveyed sensuality, soulfulness, yearning, and vulnerability. That last quality is really interesting to me, because it’s what all the great soul men, in their own way, have been able to convey without coming off as simps: Donny Hathaway, Luther Vandross, Isaac Hayes, Teddy Pendergrass, Barry White, Otis Redding, and the list goes on. Some of these men had incredibly macho images, and definitely created music that bolstered that aspect of their personas, but they could also be nakedly vulnerable, illustrating the complexity of Black male interiority. I think Lewis was in that camp in his very own way.”

Lisa Jefferson, who started at Elektra in 1990 and worked with Keith Sweat, Anita Baker, and Brand Nubians, remembers well the time she spent with Lewis. “He was very friendly, and he talked about his mother a lot. He thought about her a great deal. He and I connected. To me, he was special.” Still, for all of the label’s efforts, Skin only sold 150,000 units, which weren’t pop star numbers.

Another label might have dropped Lewis, but Elektra Records stuck with their investment, now determined to make him commercial. They planned a follow-up album with producer/songwriter Glen Ballard, who had previously worked with Michael Jackson and Paula Abdul. In the winter of 1994, Ephraim Lewis was sent to Los Angeles to record with producer Glen Ballard. During that same period Ballard was also in the studio with Alanis Morissette, working on Jagged Little Pill. He was impressed with Lewis’s work on the five tracks they completed. “We were doing wonderful stuff,” Ballard told Billboard in 2001. “He had this incredible voice. He left the studio one day, was going back to England for a week, and he died that night. I’m still spooked by it.”

Spin writer Charles Aaron interviewed Ballard fourteen years later. “Ephraim just didn’t get enough examples of his work for people to know how good he was. It’s such a shame.”

In the fall of 2019, Reliving My Youth podcaster Noel Fogelman posted a tribute to the late singer. “I dedicated an entire podcast to Ephraim because I felt his music fell through the cracks,” Fogelman says. He became a fan in 1992 after seeing the “Drowning in Your Eyes” video on VH1. “There really wasn’t anyone like him at the time. Grunge was emerging, and new jack swing was still around, but Ephraim’s music was in a class of its own, an alt-soul sound that was almost like a male version of Sade.”

Fogelman invited Hope Silverman to be his guest, and the two shared their memories and hopes of Lewis’ legacy. “Today, he is a forgotten artist,” Fogelman says. “If his tragic death took place during the internet age, there would’ve been a movie and a documentary based on him. The unfinished work on his unfinished second album would’ve seen the light. If one person discovered his music as a result of my show, then I did my job.”

In addition to recording his follow-up in 1994, Ephraim Lewis, according to reported boyfriend Paul Flowers, was on the verge of coming out of the closet. Certainly there have been gay soul singers, but with the exception of Valentino, whose 1975 track “I Was Born This Way” was released on Motown, and disco queen Sylvester, not many have come out of the closet. Writer Craig Seymour, who wrote Luther, a biography about Luther Vandross, says, “It would’ve been a big move for Ephraim if he had had the opportunity to come out. I doubt if there would’ve been a backlash, because he wasn’t trying to appeal to the mainstream Black community, but, instead he was trying for a different kind of audience.”

Hope Silverman says via email, “In a weird way, had he come out back then, the fact that he was British would likely have made it seem more ‘acceptable’ to a lot of people in the U.S. It would surprise no one that a male British artist was gay, regardless of race. It seems engrained in pop music history to assume gayness or bisexuality in British rock stars, from the Beatles and their ‘long hair,’ to Mick Jagger, and obviously on through Bowie. However, I do think it would have interfered with getting on [American] Black radio.”

Ernest Hardy says, “Since Lewis was reportedly proudly settling into his identity as a gay man and, according to some people close to him, going to be open in his music about that aspect of his being, it would have been fascinating to see where his work took him.”

Author Doug Cooper Spencer’s web portal dedicated to celebrating the Black LGBTQ community has an entry written about Lewis. According to the site, in 1993 Lewis broke-up with his girlfriend in England and began dating a man named Paul Flowers. “We met in Sheffield Botanical Gardens by chance,” Flowers remembered. “I was openly gay, but Ephraim wasn’t ready to call himself gay at the time. We arranged to meet again and just sort of fell in love. Ephraim had an incredible presence. He glowed with energy. I was always amazed at how people reacted to him. By early 1994, the affair had become a life of domestic bliss.”

Black Gay Blog editor Paul Boakye says, “At the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis, then, coming out wouldn’t have been an easy thing to do for a musician, especially a Black one.” Still, while Lewis might’ve displayed reserved behavior in England, once in America it was a different story, with the singer becoming engrained in the Los Angeles/West Hollywood gay scene, where no one knew him. He could swagger, sway, and surrender.

Nevertheless, for all the sunshine in Los Angeles, it can be a very cold place filled with vice and vipers. “Pretty much as soon as he touched down the singer fell in with some questionable company,” wrote Jeremy Simmonds in The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars. “Now openly gay, Lewis wanted to use his incipient fame to promote image to other Black gays… the downside of all this was Lewis’s increased drug use, particularly methamphetamine, the substance of choice in the West Hollywood gay community.”

David Nathan says, “When I met him, I would say I thought he was the kind of man who would likely have a charismatic appeal to both men and women. In retrospect, the song ‘Skin’ seemed to say a whole lot about what Ephraim may have been struggling with emotionally. It’s a song I can personally relate to and I’m sure many others who deal with the ‘challenge’ of how to be ‘in the world’ but not ‘of the world.’ The lyrics are deep and the haunting quality of his music suggests there was a melancholy sadness that found expression in his art.”

On March 17, 1994, after a recording session with Ballard, Lewis went back to his apartment complex at 1710 Fuller Avenue. It was a quaint block of modest cars, telephone poles, and palm trees. The next morning at 7 AM, police received calls that a naked man was “messing about” in the courtyard. When the cops arrived, they claimed that Lewis began scaling the building and leaping from balcony to balcony. Looking at the picture of the building on Google Maps, I see that the balconies are close to one another, but it’s difficult to imagine Lewis “scaling” the structure as though he were King Kong.

According to police reports, Lewis was flying high on methamphetamines when they chased him through the building, and what happened next has been debated for decades. Writer Jeremy Simmonds, author of The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches, wrote, “Lewis missed a jump and fell, hitting the courtyard below.”

Meanwhile, the LAPD from the Hollywood Division, no stranger to controversy when it comes to Black suspects, claimed they tried to talk Lewis down, but he was “acting irrationally” and “incoherent.” Lewis, they claimed, ran to a fourth-floor balcony, where police tasered him. The police say he then jumped to his death.

On April 30, 1994, UK newspaper the Independent published a scathing article that basically accused the LAPD of murder. “Naomi Hobbs, the dead man’s cousin, who is a barrister, said yesterday, ‘Ephraim was murdered by the police. Words fail me as to why they used a stun gun on someone standing on a balcony. They didn’t just use it once but three times, and as soon as they used that gun, Ephraim was bound to fall and bound to die. It was so reckless.”

The police admitted using a taser gun on Mr. Lewis before he fell, but claimed it had “no apparent effect.” In the end, suffering from head injuries, Lewis died that same day. However, Lewis’s death was ruled a suicide by the coroner. A month later, his body was transported back to England and buried in his hometown. “He was like a bright star that you see zooming across the sky, and then it’s gone,” Lisa Jefferson says. “I think about him often and wonder what would have happened with his music. He was so good, but his time with us was so short. He was here and gone, and that was it.”

Twenty-eight years after Ephraim Lewis’s death, I try to keep his flame burning bright by social media posting YouTube links of his 1992 The David Letterman Show appearance, as well as the videos to “Drowning in Your Eyes” and “It Can’t Be Forever.” There is a timeless quality to Skin that can be heard in the vanguard of soulful experimentation and avant-pop of the music. The singer might be gone, but the genius of Lewis’ musical legacy is forever.

Note: This piece originally appeared in issue 3 of Maggot Brain—one of the best music magazines you will ever read—edited by Mike McGonigal. Subscribe to Maggot Brain here.

Thank you for writing this Mr Gonzales.