Because I was born in 1994, many of the memories I attribute to the 1990s are vague, dreamlike snippets that have likely blended with better remembered anecdotes of the early aughts. As time progresses, it becomes harder to differentiate between recollections that occurred at age four or five versus six or seven. What remains certain, however, is the considerable impact the last decade of the old millennium has had on me and culture at large.

Maybe to some, the ’90s represent the last rattle of analog as a marker of authenticity. Streaming had not yet countered the important possibility of radio hits, high album sales, or box office sweeps. Fast fashion was burgeoning, but few could have predicted that noted retailers like Zara and H&M would be so outpaced by the automation of Shein. Though internet forums and chat rooms provided global connectivity, we had not yet encountered the instantaneous momentum of social media that we’re now so accustomed to. For others the ’90s may mark the tail end of the so-called “golden age” of hip-hop, the last classic era of rock, or the final time a subculture could truly be underground.

As a child in the mid-aughts, the ’90s grazed my fingertips as I fashioned my taste in media. I’d narrowly missed coming of age in a decade that was obviously cool. This was evidenced by its lingering influence in alternative styles like oversized flannel, which I collected from various Goodwills. Commercial sensations like Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and “Juicy” by the Notorious B.I.G still frequently played on local radio. How could that decade not shape me?

Movies and their accompanying music have long reflected the culture of their times, too. The 1990s and early 2000s saw the proliferation of adaptations, especially the plays of William Shakespeare. Most chose to either stay the route of loose representations that retained modern styles and talking, such as 10 Things I Hate About You, or be period pieces where the characters spoke in verse, like Much Ado About Nothing. Baz Lurhmann’s 1996 film William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet was both.

Set in the fictional city of Verona Beach, Lurhmann’s lurid take on this famous tragic love story is perhaps the most famous adaptation of the last few decades. Drawing on ’90s dance culture with a dizzying fast-pacing, Romeo + Juliet moves like a euphoric fever dream. Though best known for its leads, Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes, the movie is anchored by its supporting cast. I was 13 when I first saw it, and what I may have missed in dialogue as a middle schooler was made up by riveting performances of actors like John Leguizamo (Tybalt) and Harrold Perrineau (Mercutio), who spoke in verse with the same casual ease I talked with friends at school.

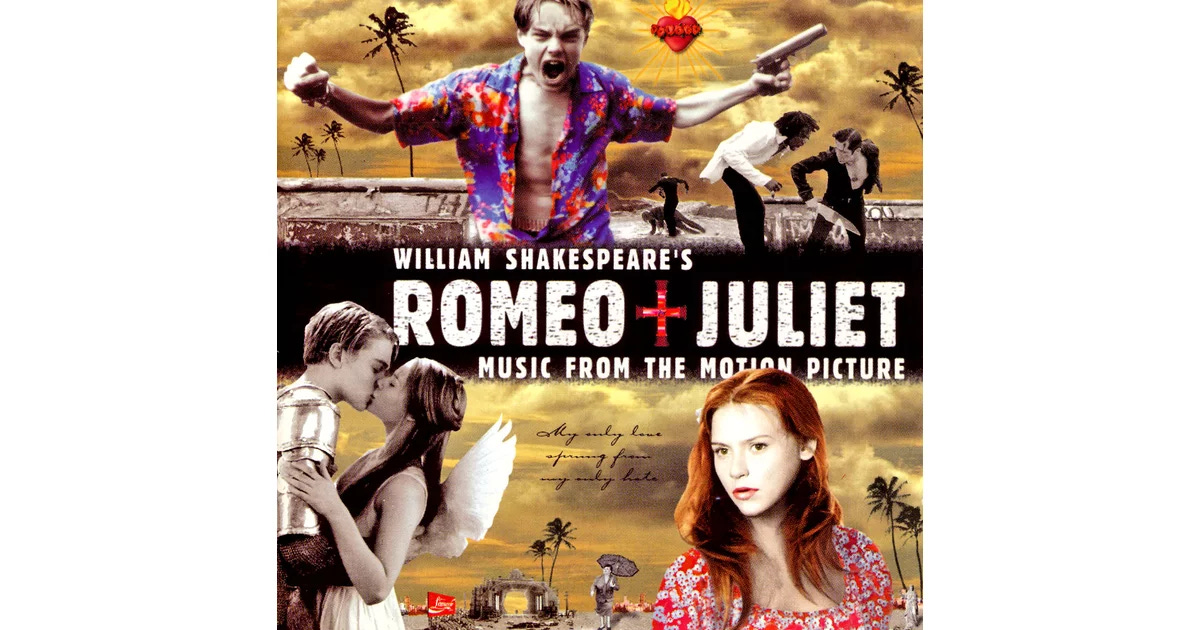

The triple platinum original soundtrack is an amalgamation of pop hits from bands like the Cardigans and Garbage, and a score created by composers and producers, Nellee Hooper, Craig Armstrong, and Marius de Vries. The music is often garishly loud and flamboyant, matching the tenor of the movie. Not merely background tracks that dissolve as a scene progresses, the songs are sometimes at the forefront—such as Mercutio’s unforgettable drag performance of Kim Mazelle’s “Young Hearts Run Free” or Des’ree singing her ballad, “Kissing You” as Romeo and Juliet wordlessly fall in love at first sight on opposite sides of a fish tank.

But the musical performance that stuck out to me most was that of a young black boy, who was also in his early teens, bellowing a rendition of “When Doves Cry.” I was not yet familiar with Prince. Of course I knew his name, his image, his cultural importance, and yet this cover, sung by Quindon Tarver, was the first version I remember hearing of the famed song.

In the movie, Romeo rushes to the church to ask Friar Laurence (Peter Postlethwaite) for help to marry Juliet in secret. As they discuss the possibility and complications of the union—such as Romeo’s supposedly undying love for Rosalind up until the last twelve hours—a boys’ choir sings to a congregation with Quindon leading.

How can you leave me standing alone in a world that is so cold?

Maybe I’m just too demanding, maybe I’m just like my father, too bold

Maybe I’m just like my mother, she’s never satisfied

Why do we scream at each other?

This is what it sounds like, when doves cry.

A little over a minute in, the song shifts from a choral rendition to a dance beat somewhat reminiscent of a sped-up C+C Music Factory, and even Freedom Williams’ “Gonna Make You Sweat (Everybody Dance Now). Quindon’s vocals are part of what makes the abrupt transition so effective. His voice—the sort of southern gospel warble that made my mom remark, “That boy can sang!”—seamlessly moves from Roman Catholic-esque to upbeat R&B. This talent is further articulated with his cover of Rozalla’s “Everybody’s Free” during the movie’s wedding scene.

As a kid hearing another kid, I came to associate these Prince lyrics with parental strife. Helmed by a single working mother raising two demanding adolescent girls, our home was one prone to dramatic outbursts and fights. My father was a specter, content to see me sporadically. This worked well since his presence caused discomfort for me because I hardly knew him, he angered my sister who rightfully distrusted him, and he sent my mom into the whirlwind of emotions that only a malfunctioned romance can produce. After an argument turned explosive—which could begin with something as seemingly benign as deciding who needed to wash dishes—I consoled myself with songs. Why do we scream at each other? I echoed, slinking into my mother’s room to apologize. Later when I finally listened to Prince’s original, I realized that Quindon’s version had omitted the verse that made clear that the song is about a bad romantic relationship.

Over the years I’ve returned to Romeo + Juliet and its soundtrack. I often return to movies and music with the same fervor that I felt on my first encounter, but sharing beloved songs with friends is equally thrilling. Showing people the cover of “When Doves Cry” has always proved satisfactory, as they hear the unexpected turn in tone, the movement from calm to somber to exuberant. When I first got the idea to write this essay, I went to YouTube to listen to it again. Much of the Romeo + Juliet original soundtrack isn’t available on streaming sites, including Quindon’s performances, but you can find anything on YouTube. Under videos of his covers were comments commemorating Quindon, who I discovered died in a car accident in April of 2021 in his native Dallas, Texas.

After Romeo + Juliet’s release, Quindon received international acclaim, particularly in Australia and New Zealand where “When Doves Cry” became a hit single. Yet his success was halted when he told someone about the sexual abuse he’d suffered within the music industry.

“I shared it with one person that I thought I could trust and confide in,” he told Double J (the ABC) in 2019. “This person went back and said something to my management at that time and, immediately, I noticed that there was this distance. They wouldn’t answer the phone when I came out to LA.”

Quindon was incredibly open about the damage that period of his life had on him—quick success, then blacklisted for trying to seek help—and open about his journey through healing and sobriety. His YouTube channel showcases his continued love and dedication to music, with covers ranging from Stevie Wonder to Linkin Park. The last video he uploaded was “Stand Your Ground,” a song about his cousin, Darius Tarvers, who was killed by Denton police at age 23. The Tarvers family is still amidst this fight and brought a civil suit against Denton, Texas in January 2022.

Across all of Quindon’s videos are comments of support, ranging from distant fans like me to friends and family honoring his memory. Baz Lurhman posted a rehearsal video of a young, shy Quindon singing “Everybody’s Free” on his Instagram in tribute. It’s clear the impact he had not just as a musician, but an enlightened, thoughtful person. In his interview with Double J, he spoke about his desire to inspire people to overcome the worst challenges.

“‘I didn’t understand why I went through what I went through,” he says. “‘But now I realize the reason I went through it was so that I could be that beacon of hope to other people that have gone through those types of things. I was used to help people, let them know that they can overcome. Because, if I can do it, so can you.’”

I think back to my middle school-self, who aimed to prove my intelligence and capacity for scholarship by taking up an interest in William Shakespeare. Saddled with typical angsty teen girl emotions, the undertaking was maybe a way to deal with insecurities and problems in our home life. When I listened to Quindon sing, I felt a loneliness that I couldn’t even fully articulate for myself but that was understood. When he sang that everybody is free, I believed.