Friends of Dean Martinez

The music of the desert shows a restless kid how to love where he lives for the first time in his life.

After I transferred from the university in Phoenix, Arizona to the university in Tucson in late-1995, I kept moving so compulsively that I barely got to know my new town. I biked to class. I hiked after class. I ditched class to hike during the week and drove all over Arizona’s rugged southeastern corner to hike the whole weekend. Half a year passed when I spent as little time in my sad cinderblock apartment as possible. I didn’t know anybody in Tucson, and I didn’t want to—not yet. My previous friendships had only helped me turn myself into a drug-dependent. And yet, I couldn’t stand to be alone or sit still either. Struggling with my isolation and anxiety about life, struggling to quit drinking beer and using drugs, I tried to work through my twitchy misdirection in the border region’s dry mountain forests and lowland deserts, taking advantage of the long highways that gave me time for silent contemplation at 75mph.

Madera Canyon in the Santa Rita Mountains, Sycamore Canyon in the Pajarito Mountains—In those first Tucson months, I saw more of this rugged landscape than many University of Arizona students did in four years of college, yet I never really saw my new city for what it was, because I didn’t take the time. I only saw the land around it.

I was restless at age 20, lost, searching for something beyond my reach and always beyond my understanding, some cosmic insight and career path that Mother Nature seemed capable of offering in a way cities could not. I’d smoked too much weed during the previous three years, and I was trying to quit in order to see find my calling. Sitting still meant dealing with temptation. Hiking kept me on track. I read a lot of ecology and nature writing books back then, and what compounded my avoidance was my belief that wilderness held the answers to all of humanity’s questions, from the meaning of life to cures for cancer, to an objective sense of right and wrong. I still believe in wild nature, but in my confused Thoreauvian worldview, urban areas became cancerous “manmade” places to escape not savor, so I escaped Tucson every chance I got, just as I had Phoenix during the previous year.

Phoenix was bland. It had a Taco Bell personality. Tucson had a singular, authentically Sonoran Desert character that evolved from its origin as a military outpost in Spain’s old northern territory, then developed in the isolation resulting from Phoenicians’ dismissal of the city as a backwater. People nicknamed it the Old Pueblo. Even before I moved there, I could see the Old Pueblo’s superiority. Prickly pear cactus grew as tall as trees. Roadrunners climbed ornamental palo verdes in the middle of town, and the lonely howl of passing trains rang throughout the night. Many streets had no sidewalks, just as many houses had no lawns. The plaster on old buildings peeled to reveal straw in the adobe bricks underneath. It was as if the city was letting you see who it really was.

Phoenix looked as engineered as Las Vegas, or worse, like bad cosmetic surgery. Central Tucson looked like an extension of the desert, natural and spacious and endearingly shaggy. I could see this when I arrived, but my philosophical views let me rationalize my unwillingness to really appreciate it; it was a city, natural-looking or not. Only when I discovered The Shadow of Your Smile, an album by a band called Friends of Dean Martinez did I finally quit running long enough to find something to value about urban Arizona, besides Mexican food and live music. I’d learned to use cities as basecamps for outdoor excursions. This instrumental steel guitar band helped me stay put, because its cinematic cowboy lounge music matched the personality of this Spanish colonial city. When I started looking at its beauty as equal to that of wildlands, I not only started feeling at home in my city, but also in my own body, and I found my sense of direction.

Bill Elm, the leader of Friends of Dean Martinez, found his musical direction on a routine visit to Tucson’s Folk Shop music store. A Tucson resident since age 10, Elm first learned violin but abandoned it for guitar in junior high because guitar was cool. Folk Shop sold tons of used instruments, and he discovered a double-8 steel guitar there.

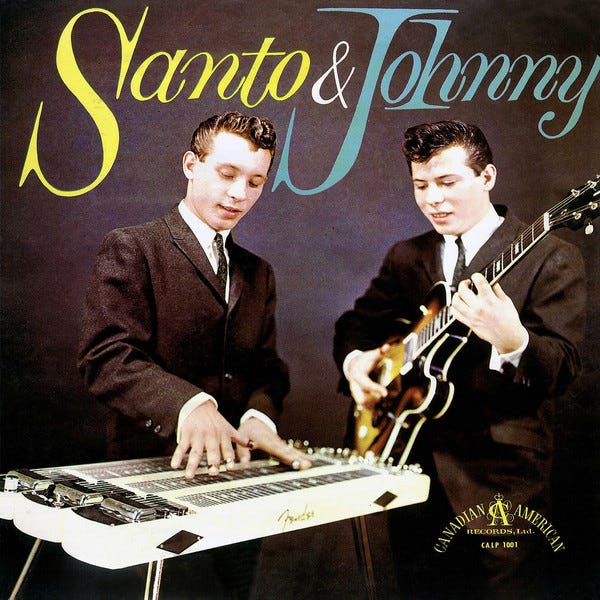

Mostly associated with classic country acts like Hank Williams, Buck Owens, and Bob Wills, steel guitar refers to a group of guitars that sit on your lap or on a stand above your knees. Unlike a traditional six-string, which hangs across your chest, steel is played horizontally. Instead of fretting chords with their fingers, players slide a smooth metal bar, the “steel,” across one or more strings to manipulate the pitch and eke out potent lingering notes that hang in the air like static from a lightning storm. In place of strummed chords or twinkling strings, the steel projects a whining, atmospheric beam of sound, as much mood as melody. What Elm called the mechanics of steel guitars had fascinated him for a while. Intrigued, he traded some musical equipment for store credit and tried to figure out this instrument by listening to Santo & Johnny records.

Santo & Johnny were a New York instrumental trio founded by two brothers. Santo Farina played steel. Johnny Farina played rhythm. Propelled to fame by their 1959 hit “Sleep Walk,” people now see the band as a mid-century novelty, like exotica artists Martin Denny and the space age composer known as Esquivel! But the brothers were innovative in their commercialism, turning Beatles songs like “Hard Day’s Night,” ’50s pop songs like “Sherry,” and jazz standards like “The Breeze & I” into instrumentals—not that the American public craved anything other than catchy choruses and memorable sing-alongs. But Elm did. He became obsessed with Santo & Johnny.

“The thing I liked about Santo & Johnny was that it was so simple,” Elm said in a 2005 interview with Linda Ray for the magazine No Depression, “and there wasn’t a lot of soloing or showmanship on the record, unlike somebody who’s trying to show you all they can do rather than just playing a pretty song. I just always kind of imagine the steel is the vocals, less a guitar and more a voice.”

Santo Farina played a triple-8. It had three guitar necks with eight strings on each. Elm’s new acquisition had no pedals, like many steel guitars do, but it had two tunings and two separate necks with two pickups and eight strings on each. It was a lot more complicated than his old six-string. No Tucsonans he knew had anything close to this. “That was one of the problems,” he said. “There really wasn’t anybody to tell me what to do with it.”

Elm showed off his steel to his friends, many of whom were musicians. His friend Van Christian was Green on Red’s original drummer before the band moved from Tucson to Los Angeles and joined the legendary Paisley Underground music scene. Christian wanted to drum again. One day in 1993, he and Elm dropped acid and listened to Santo & Johnny LPs. Then, according to a 2017 Tucson Weekly profile by Xavier Omar Otero, the idea hit them: They should do a steel guitar cover band. So Elm played double-8, Christian played drums, and Clif Taylor, known by his burlesque name Chick Cashman, played guitar.

Because steel appears frequently in country music, it’s a common sound in the Southwest. It wasn’t a sound you heard frequently in underground music in the early 1990s. Nirvana and Pearl Jam ruled the airwaves in 1993, and the insurgent style that came to be known as alt-country hadn’t yet established itself in the larger musical underground, where it got popularized by the bands Whiskeytown and Uncle Tupelo, the indie label Bloodshot, and the magazine No Depression. Country blared everywhere down in Tucson, from dive bars to trucks stopped at intersections, along with Norteño, cumbia, Tejano, and Ranchero. Naturally, rock musicians in Tucson started dabbling with country instruments before country got trendy. But Elm wasn’t interested in playing country.

“Having an instrumental band was an opportunity for me to learn to play steel,” he said in Salton Sea, a documentary about the band. “So I started adding effects and discovering that it was a much more intriguing instrument for me to not just try to cop country licks, or sound like Buddy Emmons or Junior Brown, and developing different sounds that I didn’t hear coming out of other instruments.”

Elm was still trying to learn when Van Christian told his drummer friend Tom Larkins about his new instrumental band at a party one night. “Tom Larkin offered us a show before we’d ever actually practiced playing,” Elm told Linda Ray of No Depression. “Rather than admit we didn’t actually have a band, we said that we would take the show. He asked what the name of the band was, and Van kind of made it up in a split second.” He called them the Friends of Dean Martin. “Van thought it sounded like a political organization.”

The Friends debuted at the Arizona Children’s Home alongside a man dressed as Ronald McDonald. “We had a total of four songs in our repertoire that we struggled to play,” Elm said. After that gig, the group considered disbanding. It was only a side-project after all, just for fun. When Howe Gelb’s band Giant Sand moved back to Tucson from Los Angeles in 1994, their arrival infused Friends with new life.

Giant Sand’s drummer, John Convertino, was a multi-instrumentalist who played xylophone, accordion, guitar, marimba, and piano. Their bassist, Joey Burns, played guitar, mandolin, and cello—pretty much anything with strings. Gelb played piano as well as guitar. Elm asked Gelb if he could accompany Giant Sand on tour as a roadie and ended up frequently performing with them. “It seemed to really quench my thirst of not having to carry it, just step back and play some piano, let Joey play, ’cause he was learning guitar,” Gelb remembered. “We would do a two-and-a-half, three-hour set—in Europe, anyway—and one hour of that is what became the Friends of Dean Martinez. It was really kinda great, really fun.”

Soon Elm and Christian’s side-project swelled with musicians whose ideas and influences expanded its range. Taylor gave Burns the guitar slot. Tom Larkins joined as a percussionist, and Convertino added atmosphere on vibraphone. Now the Friends of Dean Martin contained members of Giant Sand, Woodcocks, Luminarios, Yard Trauma, Green on Red, and Naked Prey, and they had a band name that would soon change.

During their first loose year together, they rehearsed in an old house at 346 South Scott Avenue, south of downtown. Tucson was a small, slow town back in the early ’90s. Worn in and inexpensive, it had character, and unlike Phoenix, it felt ignored. It stood 60 miles from the Mexican border, which perched Tucson, in a sense, on the edge of national consciousness. The national news always discussed Midwestern blizzards and D.C. political imbroglios. Nothing newsy ever happened down here, and no one seemed to talk about Tucson except people in Tucson. This gave it the feel of an afterthought, somehow separate from the rest of the country, but in a liberating instead of neglected way. To many Phoenicians, it was a dump. To many Tucsonans, Phoenix was the dump—a sprawling monotony of chain stores, strip malls, and too many edged lawns. That’s definitely how I’d viewed it growing up there.

Train tracks ran through the center of Tucson. Biking or driving, you often found yourself waiting for a train to pass. Albums recorded at Wavelab Studios picked up the horn and rattling wheels, imprinting the location on many sessions. The tracks also divided this part of the city.

On the north side lay the Fourth Avenue commercial district, essentially a row of head shops, bookstores, thrift stores, restaurants, and a co-op, all colored tie-dye and dressed in Dave Matthews pants, right on the edge of the university. Downtown lay south of the tracks. The historic Hotel Congress formed its social hub, the old brick edifice flanked by a vacant dirt lot, right where the Fourth Avenue bridge emerged from beneath the tracks.

Downtown Tucson wasn’t vacant, but it was no destination either. That was part of its charm. It had no “craft pizza” then like it does now, no upscale sushi or ramen restaurant. When I arrived, it had a chain bagel shop on one corner, Wig-O-Rama on another corner, a bank, the Crescent Tobacco Shop and Newsstand, a Walgreens—until it closed—and the legendary Chicago Music Shop. Tucson’s commercial city center had thrived during the 1940s and ’50s, then degenerated in a vacuum. Business’ signs faded in the sun. The trash can lids often lay beside the trash cans. Warehouses still housed wares or art galleries. In the early ’90s, the cool people went downtown to eat late-night greasy food at The Grill and see bands play at Hotel Congress. City workers ate Mexican food at Cafe Poca Cosa. The average college kid didn’t go downtown. They stayed in the sports bars and hippie head shops on the north side of the tracks. Before Americans started leaving the suburbs to return to dense, walkable city centers in the early 21st century, they fled downtowns like Tucson’s. Low property values here favored renters. Many lower income families rented the area’s small, cactus-covered houses and historic apartment buildings, so it wasn’t something that oblivious gentrifiers would call a “blank slate.” People lived here. Many Mexican-American families had for decades. But central Tucson’s run-down, stepson character also made it a secret frontier, a kind of laboratory where bohemians, outcasts, and musicians could do what they wanted because the rest of the country paid Tucson little attention.

Tucson was Phoenix’s antithesis. That’s how Tucsonans liked it, but the slow pace of life could weigh on people. Some loved it. Others grew bored. Many Tucsonans made things in their spare time, and like musicians in late-80s Seattle, when Seattle was uncool, Tucson musicians enjoyed creative freedom.

“There wasn’t anything else to do but drink Tecate and play music. The ultimate goal was to get to the point where we could play in the lobby of Hotel Congress on ‘Downtown Saturday Night,’ get some free drinks, maybe dinner,” Elm told Tucson Weekly’s Xavier Omar Otero. “It was in my mind a lofty ambition, because [legendary guitarist] Rainer [Ptacek] used to play there and pretty much anything he did was beyond cool.”

Despite the band members’ combined talent for songwriting, they struggled to learn more Santo & Johnny covers. “Honestly, we couldn’t figure out a lot of the songs on the records, so our set was only four or five songs,” Elm said. They wouldn’t retire the band though. “For everybody except me, it was a chance to play a different instrument than they normally do.”

Pairing steel with vibes was a revelation. Indie bands didn’t do that. To many people my age, vibraphone was for high school band practice. It’s what you heard on your grandpa’s lifeless jazz records. The cool musicians you looked up to didn’t add vibes to their subversive sonic experiments. Their attitudes came from fuzz pedals, emotional distance, and psychedelic jams. That’s part of what made the Friends so cool: They made music they liked instead of what other people wanted. In the process, they created something completely new, even if few people knew what to call it besides “desert jazz” or “cowboy lounge.”

In a stroke of good timing, mid-century lounge music had come back in vogue in the early ’90s. Numerous indie bands incorporated lounge elements into their music, shaping a scene that critics labeled “Cocktail Nation.” Stereolab helped kick things off when they released Space Age Bachelor Pad Music in 1993. A Kentucky band called Love Jones released Here’s to the Losers the same year. In London, the High Llamas released the critically acclaimed album Gideon Gaye in 1994 and galvanized a more global lounge revival. Esquivel!’s and Les Baxter’s mid-century albums started reappearing in indie record stores, and all those tiki lamps and Easter Island mugs collecting dust on vintage store shelves took on a whole new appeal.

Recognizing a trend, in 1996 Capitol Records started packaging compilations with titles including such buzzwords as cocktail, ‘swingin,’ and tiki. Time Warner and BMG repackaged Esquivel!’s music for a new generation. The 1996 movie Swingers went further, setting its narrative during the ’90s swing music revival to blatantly capitalize on the same retro phenomenon. To me, the swing revival quickly became inauthentically lame, with all the costumes and posturing, but the lounge thing was refreshing.

During a time when too many rock bands aped Nirvana’s and Pearl Jam’s styles, whining through their bad Eddie Vedder impressions to land a lucrative hit, the sound of marimba echoing under soft, breezy symphonies offered a welcome counterpoint. I loved Nirvana and Soundgarden, but I had already gotten deep in the contiguous ’90s surf music revival to infuse my life with something different from the grunge era’s darkness and boot-stomping aggression. Although lounge was recycled, it felt novel. The Friends Dean Martinez were the most novel and, to me, blew all those instrumental bands away. Fortunately for them, Seattle’s Sub Pop Records was rebuilding after constant financial miscalculations nearly killed it.

Like most ’90s kids, I knew Sub Pop as the savvy marketers whose engineered hype helped “sell the world on Seattle,” in cofounder Bruce Pavitt’s words. They were home to such guitar heavies as Mudhoney, Soundgarden, Tad, and Nirvana, who themselves became the talk of early-90s youth culture. Despite Sub Pop’s visibility, the label kept losing money. Its cofounders couldn’t keep track of their spending. They had a vision, but they didn’t balance their cash flow with their ambitions. Things got so bad in 1991 that they let every employee go. Fortunately, that year, Mudhoney’s briskly selling album Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge infused them with enough capital to keep the business running. When Sub Pop couldn’t pay their flagship band—their friends—the nearly $75,000 owed to them for the album, Mudhoney signed with a different record label. To stay solvent, Sub Pop added a clause to Nirvana’s contract so that when the band left for a corporate label, Sub Pop got some money, and the ensuing profits from Nevermind funded the label’s triumphant return. As it emerged from its in-the-red period, the label branched out in other musical directions, signing indie bands with quieter, poppier sensibilities in place of fuzz pedals and Drop D tuning. In a few more years, it would release albums by The Shins, Fleet Foxes, Sleater-Kinney, and The Postal Service, reinventing itself as a diverse indie label under partial corporate ownership. For now, it kept taking chances.

In 1994, Sub Pop got in on the lounge revival when it signed the Boston band Combustible Edison and released their debut I, Swinger. The Friends of Dean Martin weren’t trying to capitalize on anything. They were far more than a lounge band, but surely the promotion-savvy Sub Pop saw a promising crossover in the Tucson collective.

After the Friends signed a record deal with Sub Pop in December 1994, Dean Martin refused to lend his name. He threatened to sue them for already using his name on their debut 7-inch record, Polena/Seashells. Sub Pop suggested the band call themselves the Friends of Dean Martini. The band didn’t like that. Elm’s roommate Mike Semple said, “Fuck Martini. Martinez!” and they found a new name that celebrated Tucson’s Hispanic origins and its increasing influence on their music.

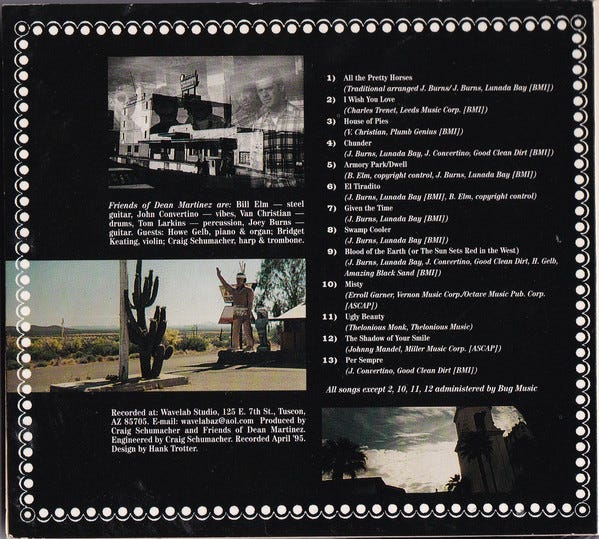

“When we went in to do our first record, we didn’t have any original songs,” Elm says. “I was trying to do a record of covers, and Joey really wanted to balance it out with some originals. So he and John started laying tracks down, and kind of a broader sound developed in the studio.”

Burns had studied music at UC Irvine and had worked at L.A.’s legendary independent SST Records. Although he played bass in Giant Sand, he was an ambitious, creative songwriter who had been busy penning his own songs and had record label connections. Burns was a sponge. He started collecting instruments at Tucson’s famous Chicago Music Store downtown. He started experimenting with the Mexican, country, and spaghetti western sounds that he’d heard in his new home, and he tried to incorporate it all into his music.

The Friends continued learning jazz standards and oddities to cover, including “Summertime,” “River of Tears,” “Sway (Quien Sera),” “Harbor Lights,” and of course, Santo & Johnny originals including “Seashells” and “Monte Carlo.” They covered jazz pianist Erroll Garner’s popular “Misty” and an obscure Thelonious Monk tune called “Ugly Beauty.” As countrified and twangy as they were, it was clear jazz shaped them in everything from their song choice to the way the drummer Van Christian used brushes and created space. Burns composed originals that fit the Santo & Johnny framework while drawing elements from Tucson to create an unusual stylistic fusion. He named his songs “Chunder,” “El Tiradito,” “Polena,” “Swamp Cooler,” and “Given the Time.” As No Depression put it: “The broader sound worked the desert atmosphere in the same way Martin Denny had worked the tropics.”

In underground music, the desert was a relatively unexplored musical influence. Besides Phoenix’s Meat Puppets and what were known as “cow-punk” bands in the 1980s, few white indie kids had drawn from the desert before. Santo & Johnny inspired the band’s basic approach: Cover anything that you like and pass it through your steel guitar filter so the song becomes your own. But it took an acid trip and diverse members to dissolve the stifling genre distinctions that keep people from seeing links between styles as seemingly disparate as country, lounge, and jazz.

Like Tucson in its unique appearance, the Friends resembled no other band. The music on their first record was a genre-defying mélange variously described as “desert jazz,” “desert rock,” “ambient,” “eclectic,” and “Americana.” People didn’t know what to do with them. Record stores categorized the band as alternative rock or jazz. In later years, their sound expanded to include electronica and heavy metal elements, creating even more taxonomic confusion. The Guardian described them as “Mogwai with slide guitars, or maybe Angelo Badalamenti in a Stetson.” One Pitchfork review, by Joe Tangari, said, “Writing a review of Friends of Dean Martinez without mentioning the desert is like writing a book without the letter ‘e.’” When people ask what they play, he just calls it instrumental music. My favorite description of the first record is still “cowboy lounge.”

They recorded their debut LP in April 1995, at Wavelab Studio down the street from my second apartment. They hadn’t planned this. “We never expected or intended to get a record deal, it literally fell into my lap,” Elm said. Other local musicians played as guests on certain Shadow of Your Smile songs. Giant Sand founding member Howe Gelb played organ and piano. Bridget Keating played violin. And Wavelab’s owner, engineer Craig Schumacher, played trombone and harmonica, in addition to recording it all.

When I moved to Tucson, I didn’t know any of those local bands existed. In Phoenix, my friends and I paid Tucson bands zero attention. We went down to the Old Puebo to shop for records. We saw Alice In Chains and the Beastie Boys play there once. We didn’t look to Tucson for cool local music. We treated Tucson as another boring Arizona place to see exciting bands touring from the West Coast or back east. I never saw the Friends of Dean Martinez’s name in the Tucson Weekly’s live music listings because I’d quit reading them. I’d seen tons of rock shows. This was my “alone period.” Even though solitude had gotten me sober, I now regret not seeing any Tucson shows that year. I might have remained oblivious to the city’s music if I hadn’t stopped at a big, chain bookstore while returning from a hike one bright day and wandered the music section.

Back then, big Barnes & Noble–type chains carried large numbers of CDs. As I paced the aisles looking for something new to sample at the listening stations, an image on the cover of one CD caught my eye. Against a black background, three photographs framed the bold white font that spelled the band’s name. There was a photo of a tall tan building towering over a gravel lot. There was a photo of a low stucco house with classic Sonoran features, and there was a photo of old tapered streetlights lining the edges of an underpass. Each image featured the same persistent blue sky I’d just hiked under. When I looked closer, I recognized the structures. The bridge was the 6th Avenue underpass. The building was the Tucson Warehouse and Transfer Company on 6th Street and 7th Avenue. The house stood somewhere in a historic neighborhood around downtown, maybe in Armory Park, maybe in the old Presidio around secluded Franklin Street. The street sign in the photo was too small for me to read. What was clear was that these structures were right down the street from my school. I frequently biked past the bridge going to and from class, the co-op, Taqueria Guadalajara, and the Toxic Ranch record store. I’d even sat on the warehouse loading bay to cool off one hot afternoon. When I put on the headphones, I realized that this band intimately knew my new town.

Brushes hit a snare drum. A crisp acoustic guitar kicked in, strumming a fast rhythm for a few bars before a steel guitar played the verse in a taught middle register. Then the steel traded lead duty with an electric guitar that played the verse in low twangy notes instead of chords. The song is a popular old American lullaby with unclear origins named “All the Pretty Horses.” Joey Burns helped arrange it. His mom used to sing it to him as a kid. I stood in the store entranced.

Some love grows with intimacy. Some love forms instantly. It felt like meeting a new person who feels like an old friend. I had known this music all my life, even before we had crossed paths. The Shadow of Your Smile put sound to the distinct images and feelings I experienced in my native Arizona for the previous 20 years—all the colors that the desert painted across my sensitive tearful heart, all the atmospheric magic of this enchanting rattlesnake land, amplified and audible for the first time and made concrete in a way that I could never articulate when I described southern Arizona to people. Although Seattle’s Sub Pop Records released this album, it was pure Tucson.

Even the song titles reflected my surroundings. “Armory Park” referred to a historic Tucson neighborhood south of downtown. “El Tiradito” referred to a beloved local Catholic shrine that honored not a saint but a ranch hand sinner. “Blood of the Earth (The Sun Sets Red in the West)” described the Sonoran Desert’s intense vermillion sunsets, which any southern Arizonan knew intimately. Van Christian’s original song “House of Pies” drew its name from a beloved mid-century Los Angeles dessert spot, but in the context of this land of diners and retirees, it sounded less like California than Arizona. “Swamp Cooler” was named for the primitive air-conditioning system that cooled houses by blowing air over moist surfaces, including damp plant fibers. I grew up with an evaporative cooling unit. It worked well during the dry first half of summer. During the humid summer monsoon season, the cooler filled my family’s tiny house with so much moisture that the doors swelled inside their frames, making them hard to open and close. Giant Sand’s singer Howe Gelb built a swamp cooler out of a disposable Styrofoam cooler and installed it in his car truck. “Doesn’t really work too well,” he told the camera in the documentary Drunken Bees. These were my people.

More than all the hikes and bike rides I’d taken, more than all the red chilé burros I ate and horchata I drank at my favorite hole-in-the-wall taqueria, or all the Charles Bowden and Edward Abbey books I would one day read, these Tucson anthems made me feel at home. Why was I always running? The band’s sound made me proud to live here. It made me want to stay in town for the weekend, to bike around its cactus-lined alleyways, learn its grid of small streets, and look as closely at its old adobe walls as I did the lime-green lichen that grew on the mesquite trees in the ravines where I hiked. This music said it was time to stop moving. The song “Given the Time” put that directly into words, almost suggesting I was missing my opportunity. But the song that initially had the strongest grip was track two, “I Wish You Love.”

It’s a cover of a 1942 French song composed by Charles Trenet and Léo Chauliac. First recorded by Lucienne Boyer as “Que Reste-t-il de Nos Amours?” (or “What Remains of Our Love?”), singer Keely Smith popularized it in America in the late 1950s with a new title and new lyrics, and Santo & Johnny eventually covered it, too. The Friends of Dean Martinez keep its sense of heartbreak and longing but strip its French connections, reconstructing it as the theme song of an unwritten desert movie. With no lyrics to impose meaning on me, this tabula rasa absorbed my own meaning as it became the soundtrack for the movie of my life.

“I Wish You Love” is languid and sleepy. It begins at full force. Drumsticks tap a cymbal, and from inside that bright precise measure, a jazzy rhythm guitar emerges over a buoyant bass line. Four seconds in, Convertino taps his mallets across the vibraphone, spreading droplets of sound that echo above everything. It’s dreamy. It drifts its way at a single mid-tempo for its entire 2:44 length and packs more atmosphere into its slow self than most 10-minute epics.

The steel guitar is a unique instrument. Played fast, it fills country bars with energized dancers. Played slowly, it sounds like summer days feel, sluggish and meandering and dozing over the beat. Even the beat sounds lazy in “I Wish You Love.” The drummer’s brushes hit the snare just behind and ahead of the beat, like a person walking with a limp and finding their own lopsided rhythm. “I Wish You Love” is a confident song that keeps its head down. It doesn’t care what you think. Under the bill of its hat, it hides from the glare of the sun and surveys the world from that thin band of shade, and when it shuffles by, it nods a friendly howdy, comfortable in its own skin and grateful for the opportunity to be alive. This is what joyful solitude sounds like.

I bought the album the day I discovered it, and I wore the cover’s cardboard edges until its black background revealed the white paper pulp inside. I took that album everywhere, the same way I had my childhood comfort blanket as an infant, rubbing and worrying and kneading it soft. The Shadow of Your Smile played at home in the morning while I sipped black tea. It played in my car while driving into the sunset. It played in my mind while I hiked oak woodland along the Mexican border and while huge white cumulus clouds hovered over the mountains that loomed on all four of Tucson’s sides. The songs themselves drifted through my days like big puffy clouds, graceful and majestic, peaceful and easy, as if to say, Slow down, man, we’re all just passing through. Enjoy the ride.

So I did. With those songs in my headphones, I biked all over central Tucson. In the scorching summer heat and the chill of winter, I peddled past vacant downtown storefronts on rutted streets free of college kids. The city had the same tranquil charm as the vacant lands I hiked. Sometimes it grew so still it resembled a photograph, not real life. I biked around taking ownership of it, learning how all the historic neighborhoods connected, waiting for the freight trains to pass, and meeting eyes with the people who illegally perched on the small ledges between cars, then I listened to those horns blow while drifting to sleep at night. As I steered my bike by old houses, I said “howdy” to the people sweeping their driveways. I said “howdy” to the women hanging laundry on their backyard clothing lines, “howdy” to the tan old men in cowboy hats who watered patches of dirt that wouldn’t ever grow grass. I got to know my city this way, face-to-face. This music pried me open, and when I let Tucson in, it became an extension of myself. Only when someone pointed out the habit did I realize how often I said “howdy” instead of “hi.” It wasn’t a put-on. My dad said “howdy,” and he got it from his dad. At this point in life, I finally started to appreciate the way Arizona had already shaped me despite my resistance.

When I moved to Tucson, I wanted out of Arizona. I thought it was because I belonged in some hip coastal city with tall buildings and lush landscaping. Like many twentysomethings hungry for life, I blamed my surroundings for my agitation, which was easy since Phoenix seemed so boring. With that logic, I assumed Tucson would be boring too. The Shadow of Your Smile let me see that Arizona wasn’t the whole problem. My attitude was. Phoenix still sucked, but Tucson didn’t. As I learned to appreciate the urban world, I recognized what I’d been missing all around me. With my old fierce hunger for music renewed, I searched for other Tucson bands. Al Perry and the Cattle came up quickly, then Naked Prey, Green on Red, Rainer Ptacek, Luminarios, Giant Sand, and my favorite of all, early-90s Calexico. The Friends of Dean Martinez brought me back to earth. It was an earth buzzing with swamp coolers.

I wondered if those Sub Pop folks in cold, damp Seattle even knew what a swamp cooler was. By popularizing Pacific Northwest bands on an international stage, Sub Pop helped transform sleepy Seattle from the Tucson of the north into a booming metropolis with sky-high property values and a tech industry reminiscent of San Francisco. Music started that process. In March 1989, before grunge broke, Sub Pop flew an English journalist named Everett True to Seattle to write a story for The Melody Maker. The label packaged the region’s music and gave it a uniform sound and look that didn’t exist in reality. That’s part of what made the label genius. But True saw the narrative and, in the words of Sub Pop cofounder Bruce Pavitt in the documentary Hype!, “was a brilliant enough guy that he could piece together a story that essentially sold the world on Seattle.” Tucson never had its own Sub Pop to exploit its music, and it never had one Everett True. But Friends of Dean Martinez guitarist Joey Burns later did a good enough job selling the world on Tucson and that so-called “desert sound” that it didn’t need either.

Starting in the late ’90s, Burns incessantly toured his own band Calexico, and he constantly talked up his desert city in the press. He knew how much the Europeans loved anything distinctly Western—cowboys, Indians, Mexican folk art, Dia de Los Muertos, the idea of La Frontera, mariachi music, and the bloody history of all those Wild West shootouts. He knew that if he could sell Europe on Calexico, he would sell the world. He did. Like post-grunge Seattle, Tucson eventually changed. In the early 2000s, the city received millions in taxpayer money and federal funding for its Sun Link light-rail system, which started service downtown in 2014. Running along Congress Street between the university and downtown, it connects what was once the vacant quarter with the commercial Fourth Avenue strip north of the tracks, and in doing so, it links the world of the old, cool Tucson underground with the bland college universe. Sun Link improved on the city’s bus service, but something got lost when redevelopment punctured the membrane that separated those worlds, some power that repelled the forces that made Tucson like Phoenix.

Since then, property values have steadily risen. Developers and businesses recognized opportunities to revitalize downtown. Now the vacant quarters feature fancy new condominiums and apartment buildings with metal sides, boutique coffee shops and breweries. The Chicago Music Store and adjacent newsstand are still there, but many longtime renters can no longer afford to live nearby. Mexican-American families and bohemians alike continue getting priced out. The empty lots bloomed and crowded out downtown’s old spaciousness, as the new businesses drew pedestrians that rarely visited before. New buildings surrounded the old Hotel Congress. These days I hardly recognize the place.

Twenty-two years later, I still own that same tattered copy of the album. All the plastic teeth on the jewel case have broken off, so the scuffed CD falls out every time I lift the lid. My car stereo won’t play it. It calls it a “bad disk.” Fortunately my home stereo plays it, so I can still blast it in summer when the sun finally comes out here in Portland, Oregon. This album earned its place in the Arizona musical canon alongside Linda Rondstadt’s Canciones de Mi Padre, Meat Puppets’ II, and songs by Stevie Nicks, Lalo Guerrero, Lee Hazelwood, and Bob Nolan‘s “Cool Water” and “Tumblin’ Tumbleweeds.” These white boys heard the sound Tucson’s blood made when it pumped through its veins, and they gave it to the rest of us to hear. Those songs still conjure strong familiar feelings about life in my native Southwest, the sense of spaciousness and enchantment, along with a painful nostalgia for the sleepy Sonoran identity that the Old Pueblo lost to redevelopment. Of course, there are improvements, but my nostalgia for my quiet desert coming of age mourns the vibe that irrevocably changed in the process.

Although I saw a new incarnation of the Friends perform in the Hotel Congress parking lot nearly 20 years after discovering them, I never got to see their original lineup perform. By the time I started going to shows again in 1997, the band that created The Shadow of Your Smile were no longer a performing unit.

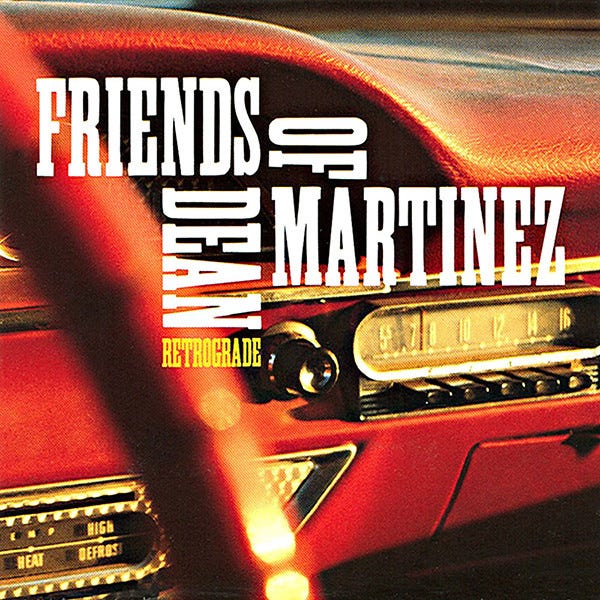

While recording their second album, Retrograde, in 1996, Burns and Elm had aesthetic disagreements. In Elm’s words, “It became apparent that Joey and I were working on two different records.”

According to Burns, “What happened is, the Friends recorded a second record for Sub Pop, and right before turning the album in, Bill decided to get rid of John and me. He’d already moved to L.A., and I guess he was tired of having too many people involved. We were pretty upset at the time—but he was the one who signed the contract, and I understand that everyone needs their own space, so I’m totally cool with that.” Gelb had experienced a similar exclusion during the recording of the first record.

After they signed with Sub Pop, Gelb said he got squeezed out by some of the others, reducing him to a side-man pianist on their project, rather than a member who shared ownership of what had seemed like a collaboration. “The weird thing was I was brought in to do so little of that record,” Gelb told Tucson Weekly. “I think it was the natural force of them—the others—just wanting to do their own thing, or perceived as their own thing or whatever. But it was kind of like a blow. I was like, ‘Aw, fuck. I was getting a good kick out of that.’ It was like, I’m not needed there… and that’s when the division started to occur, and it was like, ‘That’s kind of a drag.’ But you stay around long enough and you go through seasons and problems and shit.”

Burns had written or co-written seven of the first record’s 13 songs. Whatever power struggle had occurred, now he and Convertino turned their attention to writing songs for their own band Calexico. Elm and Gelb always knew that Burns wanted his own band. Van Christian stayed on drums for the second record, and composer Woody Jackson co-wrote many songs with Elm. The album contained a darker element and less spaghetti Western. Elm saturated his guitar with more effects, giving some tunes a beautiful wicked bleakness. Others had the slow, acoustic feel of the first album, minus the ever-present xylophones. Naturally, they covered two Santo & Johnny songs: “Monte Carlo” and “Rattler.” There seems to have been bad blood between Elm and some of the other original members, a difference in musical ambitions, but the lineup’s dissolution meant that Elm became the leader of FODM, as fans later called them, and could play the instrumental music that he wanted to play.

“I think that’s the freedom with the band,” Elm told an interviewer in Brussels. “We’re never going to have a radio hit, so why not experiment? Do what we want?” As Elm explored his instrument, he learned how to add effects to produce a whole new range of sounds you don’t associate with steel. If you could add distortion, reverb, and fuzz to a six-string, you could do the same to steel. Each album sounded different than its predecessor.

The first album’s soundtrack take on the West was half its appeal, but some say it’s an inauthentic representation, the spaghetti western version of the desert, copied from the style of an Italian guy scoring soundtracks for films written about the Southwest by another guy who likely never set foot here. In Tape Op magazine, Howe Gelb recounted how, in 1999, he told Burns “that you come here from California, from the coast, and you’re totally sounding like some Italian representation of a Western, and that’s cool.”

Elm’s old roommate Mike Semple, who later joined on guitar, clarified this desert connection: “The music we play supports things well, in the sense that it might be considered background music or whatever. It accents things well, and I think that that area of the country is very compatible with that because of the vastness and the openness. It kind of leaves space for interpretation.” For him, their music shares structure, not themes, with the Southwest. “I think leaving things open and not entirely filling up all the spaces is the commonality between the music and the desert. Not necessarily that it’s twangy or cowboyish. It doesn’t necessarily have to be like that to leave space for things to come in.” Without meaning to sound self-congratulatory or difficult, Elm says, “It kind of defies category.”

After releasing The Shadow of Your Smile in 1995, Friends did a brief tour opening for Vic Chestnut.

It was a short-lived period, and to me their best period.

Since their first record, the band has remained a rotating collective led by Elm. They’ve released a total of 11 albums and developed a cult following. The Russian edition of Playboy called them the “Greatest Guitar Band on Earth!” The Guardian wrote about how Elm’s FODM created the music for the Wild West video game Red Dead Redemption, which won Best Original Score at Spike TV’s 2010 Video Game Awards. It’s nuts. Video gamers know the band’s name. They composed soundtracks for Grand Theft Auto V and L.A. Noire. They scored Richard Linklater’s 2006 adaptation of the book Fast Food Nation. They scored a documentary about California’s Salton Sea. They even played live scores to the silent films The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari and 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea in theaters in Austin and Tucson. I attended one. It was powerful. They’ve come a long way from the Hotel Congress lobby.

They still perform live. In February 2017, they did a two-month-long Sunday night residency at Tucson’s tiny Owl Club. Occupying the old Brings Funeral Home building, the club stands one block north of the band’s old Scott Street practice space. Elm told Tucson Weekly that they were returning to their roots from The Shadow of Your Smile era. “We’re going to explore the original sound a little more.”

Still, it saddens me to look back on my life and think how they’d regularly performed just blocks down the street from my apartment—at Club Congress and in the Hotel lobby, just as Elm had envisioned—and I missed it. I might not have gone even if I had known about those shows. I wasn’t ready to come out of my shell yet. The original FODM and I were doomed to miss each other by a year. But by the time I considered myself a proud Tucsonan at least I had found them and had found Calexico and was ready to find myself there. The Friends of Dean Martinez showed me the way. “I Wish You Love” seemed to be wishing me love directly, right when I needed companionship.

*Note: This essay originally appeared at Longreads, in a similar form, written with this ’90s music memoir idea in mind. My deep thanks to editor Sari Botton, who worked with me on it during our time at Longreads.

I haven’t heard this band, but you’ve bought them so to life I can’t wait to wake up and blast them (it’s 2am here in Australia and I have a sleeping child beside me) because I’m already enamoured of them after reading this. Such an evocative essay.