Giant Sand's Wanderlust & Whimsy

Writing in a lost state of being, where things have a habit of changing, and reinvention is the only constant.

Howe Gelb has a simple philosophy for his music and life: “The word is veer,” he says.

Three years ago, this nice Jewish boy from Scranton, Pennsylvania, veered from Arizona to New Mexico, to a bar-red, two-room cabin on a little ranch in California's Mojave Desert known as Rim Rock. These days, he spends a lot of time here with his five-year-old daughter Indiosa Patsy Jean, but the two plan to veer back to Arizona so Patsy can start kindergarten.

Gelb's band Giant Sand started making its rambling music out here eight years ago, but Gelb likes to play down the obvious. "I can't claim any affinity to the West," he insists. "I just came out and liked it better than what I'd seen before. So I stayed."

Gelb claims writers overplay the "desert thig," though you could say that much of his music sounds as eerie and mystical as a Mojave wind. "It's not that big a deal for the music you make," he argues. "The only good the desert does is just to basically let you see who's coming before they see you—to have elbow room, just to be spread out, just to be away."

Anyone familiar with Gelb's output—nine Giant Sand records (including one best-of and one collection of outtakes), three by his honky-tonk alter-ego, the Band of Blacky Ranchette, and one solo LP—would recognize his peripatetic tendencies. A man whose favorite recent movies are Unforgiven and the surreal French cannibalism comedy Delicatessen, Gelb's musical interests veer toward tradition—from Dylan and the Velvets to Motown, Monk and Merle—but he bends it forward and backward, sideways and diagonally. He fucks with it to suit his own vision and to suit the times, always keeping himself and his audience guessing.

How Gelb started out playing it straight, with a majestic blend of Neil Young, blues, country & western, punk rock and psychedelia. It jelled on his third album, Storm (What Goes On, 1988), a sort of soundtrack to an 80s spaghetti western that could have been scripted by Jim Thompson and starred Lou Reed and Johnny Thunders.

Since Storm, it's been impossible to predict Giant Sand's next turn. The Love Songs (Homestead, 1989) added drummer John Convertino and former Green On Red keyboardist Chris Cavacas to the nucleus of Gelb and bassist Paula Jean Brown (Indiosa Patsy Jean's mom and Gelb's wife at the time, who has lasted as a friend and musical collaborator even though the marriage didn't). The Love Songs is a stunning mix of hazy blues, soulful, searing guitar, hard pop structures, rollicking organ, poetry and Gelb's shamanistic preaching about love and desire. "Paula and John sound like a hit machine together," he says. "It's so great because of them holding it down, and me and Chris doing the righteous veer—that's the contrast."

By the time of Giant Sand's fifth album Long Stem Rant (Homestead, 1989), the group was down to Gelb and Convertino, two jam-crazy musicians trapped in a little red barn in the desert with no safety net, searching for noises nobody'd ever made before and songs they might not be able to remember after the tape stopped.

The self-released Swerve came next, making room for a large troupe of musicians, including members of Poi Dog Pondering and Black Baby. Julianna Hatfield, whose warbling, together with Gelb's piano, provided the album's highlight. The song "Former Version of Ourselves" illustrates Swerve's scope, careening from a fat saxophone to a hard boogie riff to a party of keyboard-driven bop to one last frantic spurt of all-of-the-above. In the following song, one of the players loses it. "I hate this kind of shit," he protests. "I don't know what the words are, I don't even know what the notes are. I'm a professional, I'm not an improviser, not scat musician!"

Gelb pulled back on last year's Ramp, mostly following a path which meandered past Hank Williams and Joni Mitchell. Guest vocalists on the album include the old-time country singer Pappy Allen and Victoria Williams, who had appeared with Giant Sand during its 1990 tour.

"We toured in Europe, and then we came back and did the record," Gelb says, explaining away any suggestion of a method. "The natural change and metamorphosis that takes place on the road really leads up to what you're going to record. Otherwise it would be like trying too hard to recreate the mess you made before, and not letting yourself go anywhere else with it."

Gelb generally prefers not to think too much about how his records will end up sounding. "Um, anything is game," he stammers. "It depends how mad we are at the record company, where we are, if we're using 12 tracks on one side so we can flip it over, or who has the keys to which studio so we can sneak in at night. Anything is possible. Me even talking about it is, uh, hypocritical. I can only tell you how they got done after they happen." His Native American-influenced desert-ese cuts in: "We get a clue, we smell something burning in the wind, and all we know is which direction it's coming from. It's the same lost state of being every time. These things have a habit of changing—they're going to veer."

Rim Rock is a weird, magical, contradictory place. You won't find it on the map, but it's up the road a piece from Pioneertown, wedged into the desert between such disparate attractions as the San Bernardino Mountains, Joshua Tree National Monument, Palm Springs, and Twenty Nine Palms Marine Corps base. On your way there, just when you think you've escaped civilization, carbon-copy America rears its head again along a stretch of Highway 62 in the town of Yucca Valley, near the epicenter of Southern California's largest recent earthquake. Every fast food restaurant and convenience store known to man pops up, as well as a few shopping centers and a local theater advertising an Elvis impersonator.

Further down the highway, on either side of the road, are miles and miles of the Mojave. Joshua trees stand watch over fuzzy mounds of cholla cactus, looking for all the world like shepherds tending to their sheep. Past Roy Rodgers Road, where desert and mountain terrain meet, a warning sign for a sharp, steep curve advises motorists to slow down to 50. It's there you'll find the track to Rim Rock Ranch, where numerous L.A. Musicians have come for weekend getaways of hiking, horses, and tranquility. Gelb is one of the few who actually set up house here. "Coming out here," Gelb says, "was like coming to Mars. And then Mars feels pretty good after a while."

Inside his cabin is a wall with more than a dozen pictures of Patsy, who has appeared on every Giant Sand record since she was born. Over time, she's progressed from a cooing infant to a scat-singing toddler.

"Paula and I kind of feel like the main reason we ever got together was to have our daughter," Gelb says. "It just hits you one day: 'Oh, this is why we're here.' Then you see the kid dance before she can even speak and you're flabbergasted. My family was broken apart so many times that I kind of had an idea what not to do, and that probably led to the main ingredient of why Paula and I simply remain [friends]."

He sees Giant Sand's records as volumes, so to speak, in a family photo album. "Throwing Patsy on the records is so I can have these little soundbites of her throughout the years. We lose so much, photos and all this stuff, but we can always go down to a store if the records are still in print."

Patsy's books, clothes, and toys are the most noticeable thing in the cabin—but there's also the guitar and cowboy hat; the poster from one of Giant Sand's first shows in Spain; the boxes of Gelb's self-released version of Ramp (which in addition to Swerve, has been reissued by Restless); an eclectic selection of other records and CDs, many of them jazz; and a small bookshelf that runs the gamut from Dante and Faulkner to O'Neill and Ginsberg.

It's Sunday, open mic night at Pappy & Harriet's Pioneertown Palace. At 77, proprietor Pappy Allen is both the oldest and newest member of Giant Sand. Red-cheeked, full-maned and looking not a day over 60, he puts out candles with his fingers as he makes the rounds of tables int he roadhouse he runs with his wife. The house band is breaking in a new rhythm section; the former bassist and drummer were two of the more than 1,800 people who hightailed it out of Yucca Valley after the earthquakes. Nevertheless, Pappy & Harriet's is packed with a crowd so eclectic—cowboys, grandmas, city folks, jarheads from the Marine base, and so forth—that if they weren't so reassuringly American, you'd think it was a casting call for a Fellini movie.

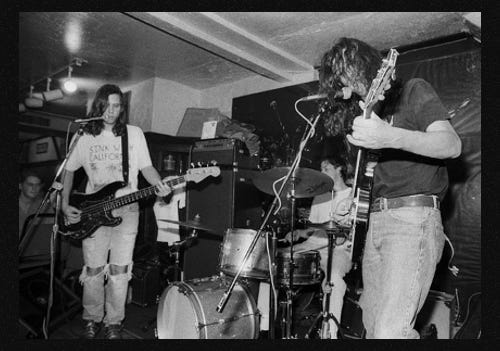

In between turns by a paunchy, bewigged, Mick Jagger impersonator, a blues singer who could make Delbert McClinton cry in his beer, and a Garth Brooks-wannabe Marine, Pappy does a few numbers himself. Music is a community activity here, and this spirit—where anyone, anything, and any kind of music goes—mirrors Giant Sand's unclassifiable sound and revolving-door membership.

Gelb is conspicuously missing from this week's mic because he had to leave Mars for a recording session over on Jupiter—that's L.A to you. Right now, he and other current members of Giant Sand are holed up at Mad Dog Studios in Venice, working on a follow-up to Ramp. With seven songs recorded and mixed, Giant Sand is nearly done with the record.

Bassist Joey Burns, just back from a five-week tour with his other band, Nothing Painted Blue, has been awakened from a much-needed nap to do some backing vocals for a song called "Stuck." The title is appropriate because Burns has had to sing the word "ironically" about 20 times in three different keys. From the sound of it, the record may be the most cohesive set of tunes Giant Sand has put together since The Love Songs—which puzzles Gelb.

"For some reason there's a lot of three-minute songs on this," he says. "We went over to Europe as a three-piece this time, went in a bit louder and tighter and more careless, and that's kind of what's happening with this record."

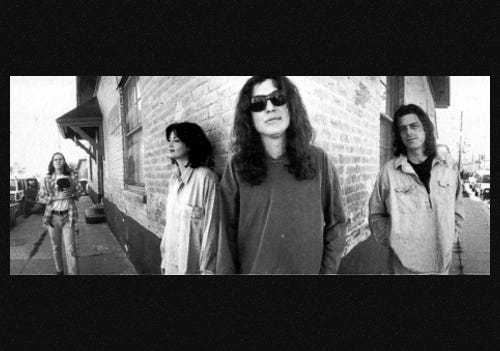

Gelb, Burns, and drummer John Convertino remain the public face of Giant Sand, though Paula Jean Brown and Chris Cavacas play on the record, too. Between Burns' classical training and Convertino's almost familiar link to Gelb, the duo is tight enough to follow wherever Gelb's brain and fingers might wander, deconstructing and reconstructing songs old and new.

"Reconstructing is too articulate a word," Gelb insists. "We're too scattered. The result is the slice-and-dice effect. We dare the songs to even be songs, dare ourselves to know what it is we're even doing, or why we're even there. That's kind of self-destructive, but it's definitely part of what has held it together."

One trick Gelb is attempting on the record can be heard in the wistful "Loretta And the Insect World," in which he patches together his vocals from different takes. Gelb uses a characteristic metaphor to explain the method: "It's like that bacteria you can get for sourdough bread. You keep it growing and you take a little bit of it and you put it in your bread and you make this beautiful sourdough. But you never use it all. That's kind of what's happened to use. That's the only way we've managed."

The sound of the new record is dominated by an acoustic guitar Gelb hotwired with pickups so he can burst into an electric sound at any moment. The songs are folky, melodic, and haunted, with stark hooks and rich backing vocals. But the remaining tracks aren't ready for completion. In fact, they haven't even been written yet. Gelb eyes a visiting journalist who's unloading a package of Tecate beer and Sauza tequila. "You got any words?" he asks.

That's the way Gelb writes. "There was always this little demon that would stop me from writing words on paper," he explains. "At first it seemed like almost a sin to listen to the devil and not put down the words or the structure, but after a while it didn't seem so bad. During Long Stem Rant, somehow it got to be okay that I could go into that barn and not worry about singing and just play with John in the swelter of July. Sometimes I would have a line written out, but mostly it just seemed like everything was a song, and you could sing about anything, because almost anything means something at some point. It was easy to do. It totally freed me up from the whole demon thing of not writing words down. I kept daring myself, when it would be time to record, to come up with a full album, and it seemed fine. Our demos became records because they're the same thing, really. There's no such thing as a demonstration tape—you just demonstrated what your record is.

A few weeks later, Gelb looks back on his most recent work from a bigger perspective. "We never figure any of this out in advance," he philosophizes. "You play guitar like you drive a car and you live your life like you're in a band. But you raise a kid on the spur and you try to get her to school on time and, amazingly, it happened: We got done with the record on Saturday, flew to Arizona on Sunday, and got Patsy to kindergarten first thin in the morning Monday."

The he veers off, worried about how he's coming across in the presence of the press.

"It's better for you to erase your tape and I don't even say anything," he suggests. "I only have one more word for you: reinvention."

Note: This story original appeared in issue 48 of Option magazine, in 1993. Thank you to author Jason Cohen for letting us republish it here, and thank you to Marci Cohen and the Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive credit for her library assistance!