“Every day it’s watching you.” —Shinji Sato

On December 28, 1998, fans packed the 1,200-person capacity Akasaka Blitz club in Minato, Tokyo to witness what was meant to be Fishmans’ final show with their bassist Yuzuru Kashiwabara.

Singer Shinji Sato, drummer Kin-Ichi Motegi, and guitarist Kensuke Ojima formed the dub-rock band while at university in Minato in 1987. Kashiwabara joined in 1988. After playing bass with the band for 10 years, Kashiwabara decided to leave for what he called family matters. He may have wanted a break from the band’s increasingly hectic schedule. He may have also tired of the singer’s increasing use of marijuana and LSD in their private studio.

Other members had come and gone, playing on various albums and tours, and left the band a trio at its core. Kashi’s departure was a big change, though, so his bandmates decided to send him off with a short, six-show goodbye tour and release this line-up’s farewell performance as a live album. They named it 98.12.28 Otokotachi no Wakare, meaning A Man’s Farewell. The band intended to continue without him. Instead of a farewell to their bassist, the recording became a document of singer Shinji Sato’s last live performance. He died from what was pronounced as a heart attack three months later.

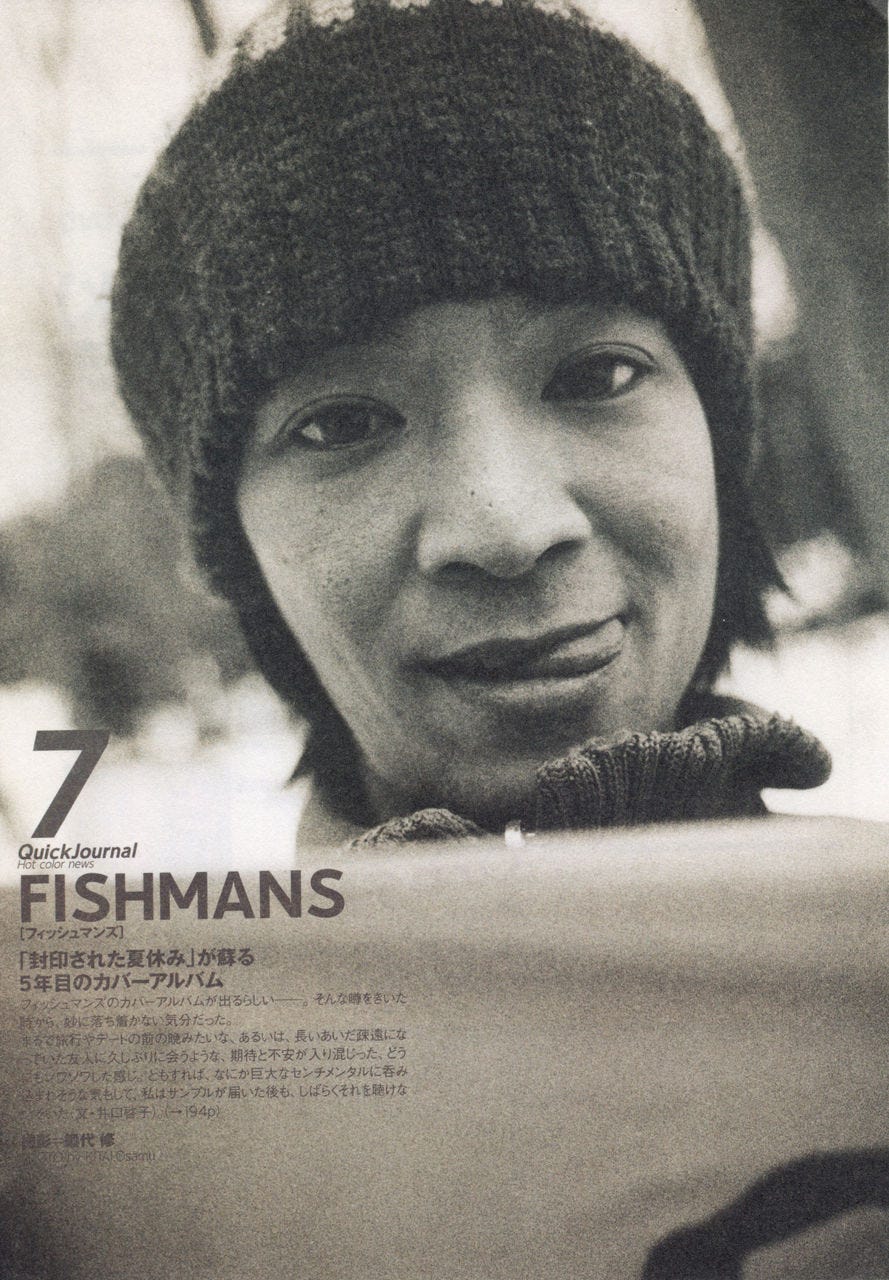

In death Sato has become an underground musical icon in Japan, and his band now enjoys much wider recognition than it did during his lifetime. Fishmans came of age in a world before the internet, back when fans relied on print magazines and TV to get to know their favorite musicians, and CDs to get their music. Thanks to the internet, Fishmans’ music keeps reaching new listeners inside and outside of Japan, where their reputation has grown. Universal Music, who owns the rights to the band’s later Polydor albums, has yet to release their albums in the U.S. and UK, or let many others license the material. Matador Records tried to license it during the 1990s, but Polydor rejected the idea. Maybe Polydor didn’t believe Western listeners would buy a band who mostly sang in Japanese. Maybe they were clinging to a small domestic money-maker before the music industry’s business model changed. Whatever the reason, that decision sealed the band’s fate, essentially locking their music inside Japan until recently, when sites like reddit, soulseek, /mu/, 4chan, and Rate My Music could liberate it, and helped turn Fishmans into what the website TV Tropes called “one of the most beloved bands you’ve probably never heard of.”

Before Spotify made the music available for streaming in the summer of 2018, and Apple Music soon after, Western listeners could only hear Fishmans from file-sharing, YouTube, or expensive Japanese imports on Discogs. Even then, super-fan Kyle Tackitt told me, you’d be hard pressed to find anything on YouTube in English that was posted before 2016. He knows. The 19-year-old Tackitt runs the Fishmans Wiki from New York State and created the thriving Fishmans discord community in 2018. He’s gone so far as learning Japanese to help translate articles and other source material. Even Amazon U.S. still doesn’t have their music available for digital download, only streaming. Polydor’s unwillingness to officially distribute Fishmans music outside of Japan didn’t stop fans from distributing it themselves.

As the years passed, Fishmans fan forums popped up online. Files got shared. Bootleg audience recordings of early shows circulated. Fans shared obscure Fishmans concert broadcasts, radio broadcasts, a digitized live recording of Sato’s first band Jikan, which means Time, and old untranslated TV interviews on YouTube, filled with conversations that Western fans can’t understand. Polydor released compilations and Sato’s demos for this new audience, who were too young to have seen the band perform in the ’90s. Interestingly, something about Fishmans spoke to digital natives, who found and clung to them. Fishmans songs are covered by Japanese pop bands like Clammbon, Polaris, and Kim Wooyong, sung in karaoke bars across the country, and an international fanbase has grown around their music, despite its limited official international distribution. The reverential way fans speak online about the band and Sato’s passing gives them a finality that can resemble a halo, a sense of poetic nobility, even martyrdom, forever linking the music with the life that it took to make it. Sato is now beyond reproach. Preserved there on stage in the Akasaka Blitz footage, young Sato will always be his best self, wearing blue and white and all that he’d accomplished artistically, with none of age’s missteps to sully his legacy.

The music is the draw, but part of the band’s appeal is its brief existence and relative obscurity, and the sense of exclusivity that obscurity provides foreigners who find the band outside mainstream culture. “That adds a somewhat personal appeal to their music,” Tackitt told me, “like Fishmans is performing just for their clique instead of for the wide audience.” Ray and Cris, the two Arizona-based twenty somethings who channeled their fandom into a Fishmans podcast, told me, “[N]ew Fishmans fans often feel like they’re stumbling on some buried musical treasure that most people are unaware of.” Like many Western fans, Ray and Cris got into Fishmans via Rate Your Music, during the band’s internet resurgence in the late 2010s. And like me, they find so much of Fishmans’ power lies in Sato’s voice. “It’s incredibly distinct and transcendent,” they said, “especially in the band’s more ethereal work from their final few albums.”

Tackitt hears an inextinguishable feeling of happiness in Fishmans’ music. “It’s this unending optimism that never wears out, that pushes even through death,” he told me. “This makes them such a bittersweet group to listen to, knowing that this playful music all comes from a brilliant mind that’s no longer with us, who was taken from the world at his creative peak.” Tackitt shares something other than passion with Fishmans: His birthday is December 28, the date of the band’s final concert.

By the time of Fishmans’ final concert, the Grunge phenomenon that ruled MTV and the American airwaves during the early ’90s had long since faded, turning it over to interchangeable pop-punk like Blink 182 and nü-metal like Limp Bizkit and Korn. Many Americans like me considered it a horrible time for mainstream music. But across the Pacific, unbeknownst to us, Fishmans was thriving in Tokyo on a diet of reggae, hip-hop, and indie-pop.

I’m a diehard music fan. I own hundreds of albums, from beat tapes to Hungarian guitarist Gábor Szabó. I’ve traveled embarrassing distances to see bands play tiny venues. And yet, I only stumbled on Fishmans in 2019, exactly twenty years after they disbanded. Once I found their 1996 song “Baby Blue” on YouTube, it led me to “Bakku Biito Ni Nokkatte,” aka “Back Beat,” which led me to their signature song “Ikarita Baby,” and I was hooked. Fishmans became my summer soundtrack, and I kept wondering: Where had they been all my life? I soon realized that the real question was: Where was I?

From “Smilin’ Days, Summer Holiday” to “Thoughts of the Night” to “Welcome to the Oasis,” they’d written so many memorable songs. Bassy jams like “Woofer Girl” and “A Moment to Forget” had such infectious grooves they left me dancing while doing dishes and drumming on my steering wheel while stuck in traffic. Fishmans did upbeat songs like nobody’s business. “Magic Love” is happy dance perfection, driven by a celebratory, joyous bassline and singalong chorus I parroted back without understanding a word. But it was the band’s unique ability to combine joy and melancholy over propulsive island rhythms that touched the deepest part of my divided Gemini nature. Individual songs like “Running Man” and “What Was That?” spanned the extreme poles of emotional expression, while others songs’ spaciousness imparted a sense of loneliness that matched the effect of Sato’s high wailing vocals.

“Running Man” from Neo Yankees’ Hotel is the perfect example of Fishmans’ ability to mix a reggae rhythm with blue melodies. Sato’s voice reaches into a divine, almost pained register, and by layering his voice over itself, he creates a sonic tapestry so mournfully beautiful that it renders the throbbing music into a backdrop for his vocals. The song’s sad power lies almost fully in Sato’s singing. Sato was one of those special artists who do not come around very often. He had that singular thing when they recorded “Ikarita Baby” in 1993 and “In the Flight” in 1997. Fans like Tackitt hear happiness at the heart of the band’s sound, but to me, melancholy was Sato’s forte, his strength, his burden. You don’t have to understand lyrics to feel any music deeply. Fishmans wrote gorgeous, poignant melodies whose sad power lies beyond language. Listen to “In The Flight.” Listen to “Paradise.” Listen to “Baby Blue,” whose chorus can elicit tears. The lyrics say ‘blue,’ but the melody is the bluest part, and it’s beautiful. Despite countless favorite songs, “Back Beat” remains one of my top favorites. It’s a dreamy, eerie masterpiece. The music has a narcotic quality. It sounds like a humid day on the beach feels and induces a kind of lethargy that is distinctly out-of-body, simultaneously creating a heightened sense of existence while imposing a sense of doom. Then there are Sato’s lyrics.

Atop a sleepy tempo and low throbbing baseline, Sato sings “Every day is watching you” in a morbid, suggestive way. How does a day watch a person? Giving a unit of time sentience, and domain over the mortals who measure the days of their lives—it’s a creepy, novel concept. Sato imagines a day that knows who we are. That makes a day a living thing that exists outside of our experience of time and that monitors, even interacts with, us like a god. As someone reportedly born with a congenital heart condition, maybe Sato had a deep appreciation of the value of time, of how fleeting it was, as if the days were waiting to determine which would be his last. This enhanced awareness seems particularly apparent when he follows “Every day is watching you” by whispering “Goodnight tomorrow.” Those two words have come to embody the fate of his band at their creative peak. Beneath Sato’s whisper, something electronic beeps—like a heart monitor tracking a dying man’s decline. In hindsight, everything assumes hidden meanings. In hindsight, “Goodnight tomorrow” suggests Sato knew he wouldn’t be singing for long.

After discovering Fishmans, I wanted to know more about the people who made this incredible music, but most reliable journalistic sources were only written in Japanese. So over the last year I’ve spoken with a number of fans to help me understand Fishmans’ story. Thankfully, one experienced bilingual translator, Motoko Matthews, and a colleague’s husband, Motoyo Nakamura, generously translated Japanese articles, televised band interviews, some of the book Fishmans Chronicle, and song lyrics into English for the first time, and put me in touch with a Japanese media industry veteran who spoke under conditions of anonymity.

By 1998, Fishmans had released seven full-length studio albums, two EPs, numerous singles, and two live albums—output that amounted to an album every year since 1991, and two albums during one year. They had fire, a charismatic lead singer, and were brimming with ideas.

That final night at Akasaka Blitz, Fishmans performed 11 songs from six of their seven studio records. Their oeuvre starts in 1991 with the straightforward, unexceptional dub album Chappie, Don’t Cry. Fun but mostly forgettable, their major label debut established their propensity for catchy, propulsive sing-alongs but provided no hint of the experimental music to come. The song “What Was That?” on their second album King Master George does. It contains the kind of sophisticated songwriting and production that would define their later albums. Where this album is far from life-altering, this song’s ethereal, contagious beauty signals the direction they would eventually take.

By Neo Yankees’ Holiday in 1993, their dub got funky and incorporated memorable poppy hooks and psychedelic elements, even as it stayed grounded in island rhythms. They kept experimenting and expanding the length of songs on their 1994 album Orange, which they recorded at Metropolis Studio in London, England. After the 12-hour flight from Narita, they dropped their baggage at their hotel and walked right across the street into Hyde Park, thinking, Oh, The Stones played a free concert here. During their stay they also visited Abbey Road, which Motegi remembered looking exactly as it did on The Beatles’ album. While Sato worked on his vocal tracks, he told the others, “I don’t want to go back to Japan yet.” The sessions were a success. Orange came out in October 1994 and remains one of their best albums. In 1995 the band transferred from Virgin Records to Polydor, and something profound clicked for them creatively inside the home recording studio they built.

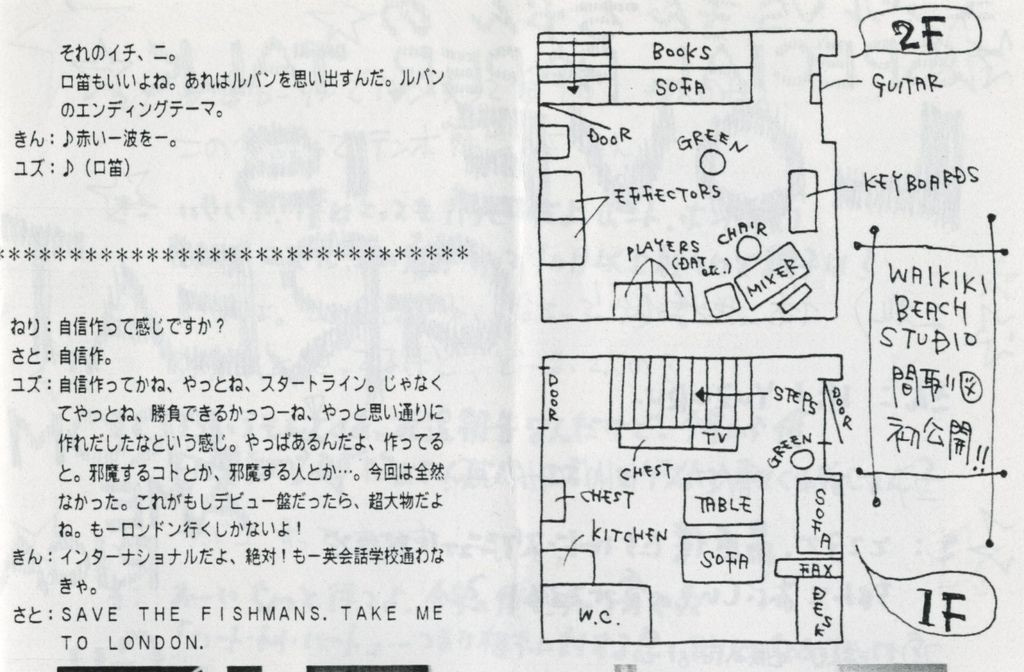

Their friend and producer Kazuyuki Matsumura, aka ZAK, convinced Polydor to pay an advance that would allow Fishmans to build a private studio where they could take sufficient time to write and record. Polydor agreed, under the condition that Fishmans record three albums in two years. The band accepted the pressure that accompanied such artistic freedom. On a Tokyo street named Awashima-dori that connected the Shibuya and Setagaya areas, Fishmans renovated a small two-story building and built their cramped studio on the second floor. There at what they called Waikiki Beach–Hawaii Studio, they could concentrate, play at any hour, and experiment with their digital recording equipment, which was still relatively new technology at the time.

In 1996 they released their first Hawaii Studio creation, Aerial Camp. Transcending dub-rock, the album integrated hip-hop ideas gleaned from TLC and Arrested Development, and electronic elements inspired by such innovators as Beck, Massive Attack, and Stereolab. Songs abandoned pop conventions and stretched between five and nearly seven minutes. Aerial Camp marked a turning point. “Everything started to look different around this time,” Sato told one magazine.

In 1996, they also released Long Season, an album that sounded different than all of their previous work and abandoned traditional notions of melody and structure. Long Season consists of a single 35-minute song divided into five movements. Released by Polydor in Japan but not overseas for decades, Long Season stands as the most dramatic example of Fishmans’ willingness to deviate stylistically from their original reggae sound and to experiment with the possibilities of expansive, ambient music. Some listeners compare Long Season to Can’s krautrock masterpiece Future Days, which the experimental German band released in 1973. Others hear echoes of Radiohead in it.

“The idea grew out of a casual conversation among the members,” author Dai Onojima writes in his two-part series for the Japanese entertainment magazine Natalie. “They felt like Aerial Camp was like one song although there were eight tracks, and they decided to make one album with only one song.” They may also have been influenced by the pressure to fulfill their contractual obligations, so they set themselves free artistically and cranked this one out.

Sato wrote most of Fishman’s songs as demos on his old Akai sampler, and the band helped flesh them out. As Fishmans drummer Kin-Ichi Motegi told The Japan Times in 2019,

“Sato had a real talent for capturing the feeling he wanted to express in sound. His style was to say: ‘Here’s the mood I’m going for, let’s see what everyone can come up with.’” In their studio, the trio worked hard to shape these demos into songs. “To borrow a phrase from Sato, we were ‘just doing it,’ but ‘just doing it’ takes real single-mindedness,” Motegi said. “It’s about devoting yourself completely to the task and moving gradually forward, until eventually you end up with something like Long Season.” Their gamble with Polydor paid off. They created sad pop songs like “Baby Blue” and haunting atmospheric slow jams like “Atarashiihito,” where Sato whistles an eerie whistle melody over the relaxing sound of rain. The guitar and bass are reggae. The rest is something entirely else.

By “just doing it,” they did more than honor their contract. Between Waikiki Beach-Hawaii Studio’s completion in August 1995 and its closure in August 1997, when the lease expired, they created three masterpieces. The third is their final studio album Uchu Nippon Setagaya, which is more stylistically diverse than seems possible across the span of 58 minutes. The title translates to “Space Japan Setagaya.” Setagaya is the area of Tokyo where singer Sato grew up. Nippon is what Japanese natives call their country in place of the name outsiders gave it. On the album, reggae baselines throb beneath disco sounds and electronic bleeps and bloops. Piano twinkles beside amplified violin and gauzy, shimmering, shoegaze guitars. Songs alternate between melancholic and joyful, grooving and ghostly, and sneak pop hooks and catchy melodies inside unconventional song structures. Uchu’s variety is staggering: The fast guitar jam of “Weather Report” leads to the lonely, skeletal “In the Flight” leads to the straight up disco-dub of “Magic Love” to the haunted narcotized dreamscape of “Back Beat,” followed by the 13-minute dirge called “Walking In The Rhythm,” which never grows tiresome, only to close with a meditative song about death. Uchu is the most fully realized expression of what Fishmans remain best known for: the style called “dream pop.”

These three albums form what the band called the Setagaya Trilogy, a trilogy linked by experimentation, their place of recording, and the way they define Fishmans’ oeuvre. If Fishmans started as a fun but conventional dub band, the trilogy’s seamless eclecticism lifted the band into the avant garde where they grabbed peoples’ attention and have kept it. In the process of creating their trilogy, Fishmans burned themselves out. As their A&R director Toshiya Sano said in a long Natalie article, “It was hard. They were saying ‘If U2 made Kuchu Camp, they would not even think about making another album for five years.’” Instead, Fishmans kept writing, recording, and performing through 1997 and ’98. As a band supported by a big record label and on the cusp of breaking out, they appeared on TV shows, opened for Pavement at Shibuya Club Quattro, and professionally recorded many of their performances, including shows at the Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall, Hirotori Namiki Junction, Shinsaibashi Club Quattro, Nagoya Club Quattro, and the Shinjuku Liquid Room. Parts of these recordings made it on to the live compilation album 8月の現状, aka 8 Gatsu no Genjō.

As beloved as the Setagaya Trilogy is, many fans consider Fishmans’ farewell live performance on 98.12.28 their masterpiece for the way it combines the best of their final albums. Like poet Walt Whitman wrote of his complicated self in 1855, Fishmans contained multitudes. Somehow those multitudes all got along on 98.12.28. It and Uchu are the best place for new listeners to start digging into Fishmans’ catalogue, because they provide a taste of the band’s entire oeuvre and all the band’s influences, passed through their strange, modernist filter. But the farewell concert recording holds a sacred place in Fishmans’ discography. This is partly because it is a farewell, partly because it’s so charged with emotion, and partly because it contains an appealing cross-section of the distinct stages of the band’s artistic life, performed by a mature group in full control of their musical powers. 98.12.28 isn’t a snapshot of a band mid-tour in their prime, a kind of “this is who we are right now” moment as their previous live album is. It’s a farewell statement loaded with pathos. And there is something especially poignant about hearing a performance by someone you know is going to die. The instrumentation is especially noteworthy. From their mid-tempo paean to complex romance, “Ikarita Baby,” to the celebratory “Smilin’ Days, Summer Holiday,” 98.12.28 lets you hear their songs stripped of studio overdubs, letting the melodies and sparer instrumentation—and often, the haunting tone—speak for themselves. As a finale that December night, Fishmans played Long Season in full.

In terms of fidelity, the live set sounds crisp, and the members play with the kind of fire that somehow marks both a hungry band at the beginning of their lives, and one who recognizes things coming to an end. They just didn’t know how close the end was.

After playing a cheery reggae song off their first album, Sato suggested to the audience that Kashiwabara’s departure wasn’t the end. It was an opportunity to, as he put it, “try and start over from the beginning.” They would compose, record, and perform as they always had, and they’d keep experimenting. The whole decade had been one long experiment, from their music to their lives as musicians – even the way they played each song differently in concert, tour-to-tour. Velvet Underground fans famously say the band never played the same song twice. Fishmans and VU aren’t comparable stylistically, but Fishmans also reworked their music in concert, like a lush, guitar-driven live version of “Running Man” that Sato played on his friend Daisuke Kawasaki’s radio program in 1993. It’s my favorite version. The band treated performances as a place to expand their range. “And, I guess we will see who will still be around in 10 years,” Sato said, smirking.

What sounds like a fan in the crowd yelled, “Don’t say that!”

Sato laughed. “I mean, I have always thought about that but, just look, the number of people here has really gone down,” said Sato, glancing down at the guitar around his neck. “But yeah, I really can’t say anything about that. So this next song makes me think that even I will probably change over the next 10 years. But, yeah, please listen to this song that reminds us that things happen in life.”

At face value, Sato was segueing into their next song, “In the Flight.” This slow, hypnotic tune is about vulnerability and reckoning with limitations, how external circumstances shape our destiny as much as, if not more than, our own choices. “Fully dependent,” Sato sings, “we rest on the air. As we fly on forever, please take care of us.” The “ten years” he refers to appear in the lyrics. Lyrics aside, there is a melancholic quality in the song’s sparseness which sound like finality to me, like footprints trailing into mist, or days that are watching you. I hear a song with the haunting tone of farewell. When you take into account what happened soon after this concert, it’s hard not to read more deeply into his comments that “things happen in life” and about shrinking audiences. Maybe it was Sato, not fans, who was shrinking. He sings:

Standing outside your door

I thought about how in ten years you will be able to do anything,

But of course that is just a lie we tell each other.

You can’t do anything,

I can’t do anything.

Although his death was officially the result of a congenital condition, possibly compounded by a flu or cold, some more conspiratorial fans claim that “heart attack” is a polite cover for a suicide.

On December 2, 1998, weeks before Fishmans’ last show, they released a 13-minute song called “Flickering in the Air.” In a 1999 op-ed, dub musician Kazufumi Kodama took Sato’s ambiguous memorial service announcement, and that song’s lyrics, as evidence that Sato took his own life.

Kodama founded Mute Beat, one of Japan’s most influential dub bands, in the 1980s. Kodama produced Fishmans’ first album and knew Sato personally, though they had fallen out of touch. “He killed himself,” the op-ed begins. “I started thinking he must have killed himself. Because we didn’t have much information. There was no rumor about sickness nor accident. A few days after, his friend who lives far away gave us ambiguous information. The invitation to his memorial service said he passed away during his recovery period.” The invitation said that Sato wasn’t working at the time because he was on sick leave. This confused Kodama, because it seemed to conceal certain facts. “However,” he wrote, “we still don’t know what happened to Sato-kun. I wonder why nobody said anything to us if he had been sick? If he died from flu or something why didn’t they say anything about the specific sickness?” Kodama cites the song lyrics as the more accurate account of Sato’s final struggle: “‘Yurameki in the air he is singing./Sunset doesn’t come./I wish you wouldn’t disappear today./I wish you wouldn’t disappear today.’ I think in this lyric he projected himself as ‘you.’”

Using song lyrics to understand a persons’ behavior is unreliable, speculative work, and yet, Kodama concludes that Sato’s lyrics and life are related, because, I assume, music was Sato’s primary form of expression: “I feel his death is his last message as an artist,” Kodama writes. “I deny the possibility that the artist’s death is not suicide.” Taken that way, then the album 98.12.28 is Sato’s second-to-last artistic statement. Some fans like Kyle Tackitt reject this idea, unwilling to believe Sato capable of taking his own life when he seems so full of it on stage. Tackitt recalls a 5chan post where someone wondered why a talent as great as Sato couldn’t just have a natural, quiet death like regular people. Does a brilliant artist need to die dramatically? “The lyrics for ‘Yurameki in the Air’ are fairly worrying in this regard,” Tackitt said, “but personally I’ve always found Daydream’s lyrics (the final song recorded at Waikiki Beach) to be more up-front about themes of death or loss. All this said, as much as I know about Sato, I don’t think he would have committed suicide. It just feels too unlikely to me.” Some fans have adopted Kodama’s theory. Others say “heart attack” is cover for something more shameful in Japan: a drug overdose.

So many young musicians died during the 1990s that historians can track the rise and fall of the West’s so-called alternative music as much by charting singles as by musicians’ losses. Andrew Wood from Seattle’s Mother Love Bone set this deadly decade’s tone when he overdosed on heroin in 1990. The infamous GG Allin overdosed in 1993 a month before The Wonder Stuff’s bassist Rob Jones. Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain and Hole’s bassist Kristen Pfaff died in 94. Blind Melon’s singer Shannon Hoon died in 95. Heroin took the life of Sublime’s singer Bradley Nowell and Smashing Pumpkin’s touring keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin in 96. A sober, 30-year-old Jeff Buckley accidentally drowned in a Mississippi River tributary in 1997. By 1997 dope was so epidemic that Portland, Oregon’s Dandy Warhols sang “I never thought you’d be a junkie, because heroin is so passé.”

Japan’s severe drug laws mean that the substances that shape the West’s underground music culture are far less rampant on the island nation. To the casual observer, the low number of annual drug arrests suggest a culture relatively unaffected by narcotics and marijuana. Alcohol is Japan’s drug of choice. Bars abound. Vending machines sell beer and whisky. But anonymous sources tell me weed and psychedelics are easy to get, and meth has been Japan’s most popular illicit substance since the Japanese mafia, known as Yakuza, began distributing it after WWII. “It is true that the majority of Japanese has a strong sense of taboo far beyond the imagination of Americans when it comes to illegal drugs including cannabis,” a Japanese media industry veteran told me. “Most of them end their lives without even knowing the smell of weed. However, it does not mean that there are no illegal drugs in Japan.”

Marijuana plays an integral role in the Rastafarian culture that created reggae music. In Japan’s reggae music scene, bands give their songs names like “Dub the Bong Around” and “Herbal Wise,” but marijuana leaves and the Rastafarianism’s red-yellow-green colors are mostly fashion statements meant to signify subcultural association. That said, joints do get passed around.

The three years between building their studio and Sato’s death were the band’s most musically inventive. “These were also the years when Sato got involved deeper into drugs,” my anonymous source told me, “while his feeling of loneliness intensified. Think about Brian Wilson back in 1966. Then you will get the idea of how Sato was like at the time. It is said that the types of drugs they used at Waikiki Beach Studio were conventional, such as marijuana and LSD. It is not clear, however, what kind of drug Sato was using after the studio closed. What’s clear is that the members were drifting apart and the situation got worse to the point where Yuzuru Kashiwabara left the band. It was also obvious to everyone that Sato was getting physically weaker and weaker.”

Sato’s drug use was an open secret to many fans who regularly attended Fishmans shows. What type of drugs did Sato take: Speed? Opioids? Pills? Marijuana and psychedelics do not cause weight loss or heart attack. But whatever substances effected his physical condition is all speculation. “After the closure of the studio,” my source told me, “Sato was doing his own things all by himself more than ever before. What kind of drug was he doing? Who was he buying from? How much was he taking? Those are the biggest questions hovering over his diehard fans.” Even 20 years after Sato’s death, neither his band members, friends, nor family have publicly stated the role drugs may or may not have played. “When it comes to the actual cause of death,” my source said, “there are no written or spoken accounts which could possibly be more than just rumors.”

Whatever the cause of Sato’s death, it spelled the end of the band.

Before he died, the group was developing Sato’s latest home recordings into songs. They released one in 1999 called “It’s Just a Feeling” (“それはただの気分さ), but most of that demo material remains too undeveloped to release. The band couldn’t continue without their main songwriter’s contributions. Using any other singer would render them a cover band. So in 1999, Fishmans officially disbanded.

Considering the final album’s title over 20 years later, it’s impossible not to wonder if the departing man on A Man’s Farewell had always been Sato. Was he saying goodbye before anyone noticed? After all, the band professionally recorded the show, and they had booked it in the same Tokyo ward where they’d formed eleven years earlier. This is pure speculation, but that circularity—connecting their end to their beginning—suggests meaning, possibly intent. Besides the music, speculation might be all fans will ever have. The music invites its own questions.

Sato’s death at age 33 assured his place in the pantheon of brilliant musicians who died young. Like the deaths of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, and Ian Curtis of Joy Division, it generated the usual speculation: Did he die at his creative peak, or did he die before he could reach his full artistic potential? For any band to go from reggae, to ambient, to space pop in the span of three consecutive albums was noteworthy enough. So was their ability to pack all of these styles on a single album. Few personalities have that many sides. Listening to 98.12.28 now leaves you wondering what masterpieces this band would have created next. But it’s unfair to treat those final albums as tragic bookends to a band that was just getting started. What you also hear in Uchu and 98.12.28 isn’t a singer getting started, but a singer who felt more deeply and who accomplished more artistically than most of us ever will in twice the time. As one fan wrote in his detailed guide to the band’s catalogue, “His death was still tragic, but if there’s anything anyone could hope for before an untimely death, it’s leaving behind an album like [98.12.28].” The band left behind other professional concert recordings, though few have been released.

“I’ve seen the tracklists for concerts such as October 10, 1998 [at the Hibiya Open-air Concert Hall],” Tackitt said, “and I genuinely think performances like that would make a worthy opponent to 98.12.28 if released properly, but so far only small portions of the concert and others have seen public release.” As a prolific collector and documentarian, Tackitt shares tons of Fishmans music on YouTube, including an audience recording of the band’s second-to-last show, on December 27, 1998. A Japanese fan recorded the show on two minidiscs and had only played it for a few friends since. When he posted about it on Twitter in late-2019, Tackitt requested a copy for posterity. Tackitt believes that the many dozens of high-quality soundboard recordings that Fishmans made between 1994 and 1998 – parts of which ended up on live-studio compilation albums like Oh! Mountain and 8月の現状, aka 8 Gatsu no Genjō – remain in the record company’s proverbial vault, wasting away unappreciated, possibly un-digitized, and susceptible to decay and fire, as famously happened in the 2008 Universal fire in Los Angeles. He doesn’t know that for a fact, but he assumes. “Ultimately I feel as if Fishmans’ musical legacy is somewhat neglected by their label, and they deserve more exposure and for more people to hear them so that maybe more full concerts could be released someday.” Misunderstood and hopeful – spoken like a true fan. We hardcore fans love a Holy Grail, and those full soundboard concerts seem to be his.

Kodama’s interpretation of Sato’s lyrics conflicts with the plans Sato described at the final show, and the plans he and drummer Kin-Ichi Motegi had discussed at the time. “We were talking about making our songs more compact again,” Motegi told The Japan Times in 2019, “going back to something more pop.” At the time of their final show, they planned to find a new bassist. Fishmans were in the midst of very fertile period, experimenting with their sound and the format of their albums. They filled increasingly large venues. Why would they stop? Surely if they continued, they’d score bigger radio hits than they already had with “Baby Blue” and “Nightcruising.” Surely they’d play the big festivals like Fuji Rock, which started in 1997, and the Summer Sonic Festival which started in 2000, and which helped underground bands find listeners who were tired of mainstream music. “That’s when it started to feel like more people were becoming receptive to what we were doing,” Motegi said of the band’s final years. “I wish they’d cottoned on a little sooner!” Motegi isn’t nostalgic or bitter, but he does regret the band’s inability to play festivals. “When I imagine Sato up on that stage now, I’m sure he would’ve killed it.” The issue was timing. We’re all at time’s mercy. As Sato sang, “Fully dependent,” Sato sang, “we rest on the air as we fly on forever, please take care of us.” Every day is watching you, and one day we say goodnight.

After finishing their third song “なんてったの,” meaning “What Did You Say,” at Akasaka Blitz, Sato addressed the crowd. “I’m pretty happy to be able to sing songs in front of a huge crowd like this,” he said. “We’re the Fishmans. Hello!” The crowd applauded. Kashiwabara -bowed behind him as Motegi scanned the room from his drum set. Then, snickering, Sato said, “Well finally, this is this year’s final live show. We really hope to do live shows next year as well as the following year. Please look forward to it.” The crowd cheered. “Yesterday Motegi did his best. As did I. Today we will continue to do our best. Please enjoy your time.” Motegi waved to the crowd, then they tore into the song “Thank You.”

“Thank you, thank you, for my life,” sings Sato.

Let’s live quietly!

Banana, melon

Banana, melon

Banana, melon

Bite it

Followed by a call to action: “Now is not the time to do nothing!” The catchy, upbeat song is a celebration and reflection on the fleeting nature of time itself. It’s that simple: Sato’s grateful for his life. Life is a fruit, and right now is “a lovely fruit time.” It’s no time to let it rot. Rather than interpreting this song and Sato’s comment to “enjoy your time” as an acknowledgement of his approaching death, this song—this whole concert—becomes a love letter to fans, an expression of gratitude, only as morbid as all acknowledgments of mortality are by their nature. 98.12.28 becomes a call to enjoy our time while we have it—whether we are able to fulfill next year’s plans, or find out who will or will not be here in ten years. Rather than hanging on to Sato and the never-ending what-ifs this beloved album generates, we must simply enjoy the music and say goodbye, just as the band had said goodbye to Kashiwabara with that fateful December concert.

On March 15, 2019, on the twentieth anniversary of Sato’s death, Sato’s parents, friends, and bandmates traveled to his grave across Tokyo Bay. By then, the building that once held Waikiki Beach-Hawaii Studio had been turned into a French cake shop and, later, a bar that did not serve fish.

Situated off Route 409 in Chiba Prefecture, the Kasamori Cemetery’s neat rows stretched across a gentle valley nestled between low scrubby hills. Colorful flowers stood on Sato’s dark polished headstone beside bundled incense and bottles of green and milk teas. As one fan observed from their own visits, there were always flowers on Sato’s grave. On this day, someone snapped a photo of the gathering, possibly the bassist, who is missing from the image. Under a cool blue sky, Fishmans’ first guitarist, Kensuke Ojima, stands beside producer ZAK, who wore the same style of sunglasses he wore in the late 1990s. Beside them, drummer Kin-Ichi Motegi, their old keyboardist Hakase-Sun, and Sato’s mother. A faint, almost obligatory smirk hung on her face. Somehow the photo appeared on reddit, where one fan wrote: “I have tears in my eyes.” In subsequent photos of the empty gravesite, a simple white sign stands above the headstone, listing Sato’s kanji name 佐藤伸治 above the name of the band that keeps him alive.