Hanging at the Mall

Nineties kids spent countless hours eating, playing, flirting, and developing autonomy in malls before changing economics killed these social hubs

If you grew up in the 1980s and ’90s, then you probably hung out at the mall. Malls weren’t just collections of stores. They were exciting communal spaces that drew some kids so regularly that we earned the nickname “mallrats.” Before the internet, people needed physical places to shop and recreate.

“Malls started becoming shopping Meccas in the ’80s,” writes Business Insider, “but by the time the ’90s rolled around, they were a full-blown phenomenon.”

The classic, fully enclosed form now known in America as “the mall” debuted in Edina, Minnesota, in 1956. An Austrian-American architect named Victor Gruen designed the so-called Southdale Center, and it became the de facto prototype for a wave of enclosed, temperature-controlled shopping complexes structured around big name “anchor” stores and interior garden spaces. As if the stores themselves weren’t attraction enough, many mid-century malls used flashy designs to lure shoppers. The first mall Gruen designed, named Northland Center, included avant garde giraffe sculptures, extensive landscaping, and spinning mobiles. Southdale Center went further. It had a twenty-one-foot birdcage containing fifty colorful birds, tropical plants, costumed Hawaiians serenading crowds, and a huge central square named the “Garden Court of Perpetual Spring.”

I was born in 1975, so my trajectory aligned with the rise and fall of the American mall and when they’d lost those mid-century elements. Growing up in a scorching desert city like Phoenix, Arizona also meant I was destined to cool off in malls’ chilling air conditioning.

Phoenix had tons of well-designed, unusual malls. There was Thomas Mall, Fashion Square Mall, Maryvale Mall, Park Central Mall, Fiesta Mall, and Tri-City Mall. Because my grandfather owned a men’s clothing store and my dad briefly worked for him, I spent a lot of my childhood in Chris-Town Mall.

Built in 1961, Chris-Town was one of the earliest to adopt Gruen’s design. In Gruen’s model, people would theoretically come to Chris-Town for the massive J. C. Penney, sit by the miniature planted palms and sip coffee inside Guggy’s Coffee Shop, and they’d discover Godber’s Gifts, Chess King, and Tony’s Shoe Repair while strolling the intentionally large distance between Korrick’s Department Store and Montgomery Ward, the two anchors.

Chris-Town was Phoenix’s third mall, but it was Arizona’s first enclosed one, and it aimed to provide the glamorous Gruen experience. It was built around three themed courtyards: The Court of Flowers, Court of Fountains, and Court of Birds.

The Court of Fountains was the central courtyard, with a low, circular fountain ringed by flowers and two stone staircases whose graceful arcs resembled those of high-heel shoes. Up until the early 1970s, an organ grinder walked the Court of Fountains with a monkey, collecting coins from shoppers.

The Court of Birds was an aviary in the west wing, complete with small bridges from which to view the sixty-four birds and their avant garde enclosures. One of the cages reached nearly to the ceiling, a cubist series of stacked trapezoids. At one point in time, the Court played host to a talking parrot named Chico, who was trained to greet shoppers by saying “Welcome to Chris-Town.”

Finally, The Court of Flowers stood in the east wing and offered more subtle charms: an outdoor, U-shaped café, and a bunch of funky, bulbous lights overhanging a small garden plot and what appeared to be a red unicorn with a bright yellow horn, but which was actually, incongruously, a papier-mâché statue of Ferdinand the Bull.

Chris-Town was so popular that other Phoenix malls slapped lids on their open breezeways and pumped in air conditioning. They also aped its novelties. Thomas Mall featured a gimmick that made Chris-Town’s aviary look as dull as a parking lot: a monkey cage outside the J. G. McCrory’s five and dime.

But by the time I came of age, in the early eighties, everything had changed. Chris-Town was still noticeably Space Age in its architectural accents, but malls were a dime a dozen by then, and Chris-Town had outlived its elegant heyday by over a decade. The pink and powder blue of the early-sixties had given way to an eighties brown, yellow, and orange schema. Everything in the early Regan Era seemed to have the sickly tint of used cigarette butts: the marbled brown floor tiles, the faux wood pattern on the trashcans and ashtrays, the ubiquitous brass poles and fixtures. It sounds gross in hindsight, but I loved it back then.

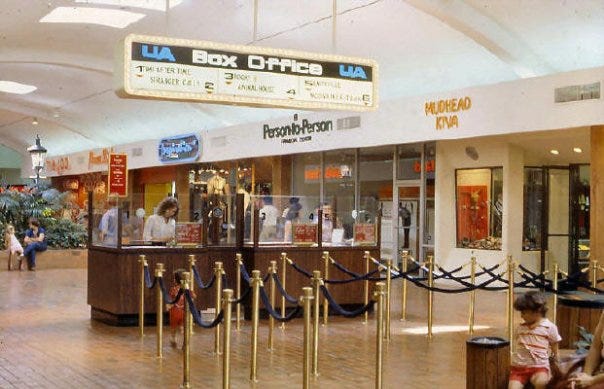

My Grandpa Shapiro’s store, The Habber Dasher, was adjacent to Chris-Town’s food court, an echoey hall enlivened by the greasy orange aroma of Pizza D’Amore and the sweet froth of Orange Julius, as well as Kay Bee Toys, the Red Baron video-game arcade, and the movie theater. My time at the mall was spent buying shockingly lifelike diecast metal cap guns at Kay Bee and then eating free samples of slow-cooked meat from the tiny gyro stall, staring in horror at the hard, sunken eyes of the whole smoked fish in Miracle Mile Deli’s cold case, or looking up at the tall escalator that led into UA Cinema. Bill’s Records and Audio was a confusing tangle of electronics to my child’s eyes, but the little kiosk that sold cotton candy and popcorn in front of JC Penny’s smelled good enough for me to hang out around it. The hot pretzels at Tempting Twisters also looked appetizing, especially combined with a banana split at the neighboring Farrell’s Ice Cream parlor, though I never at that either. Mostly, I wandered around.

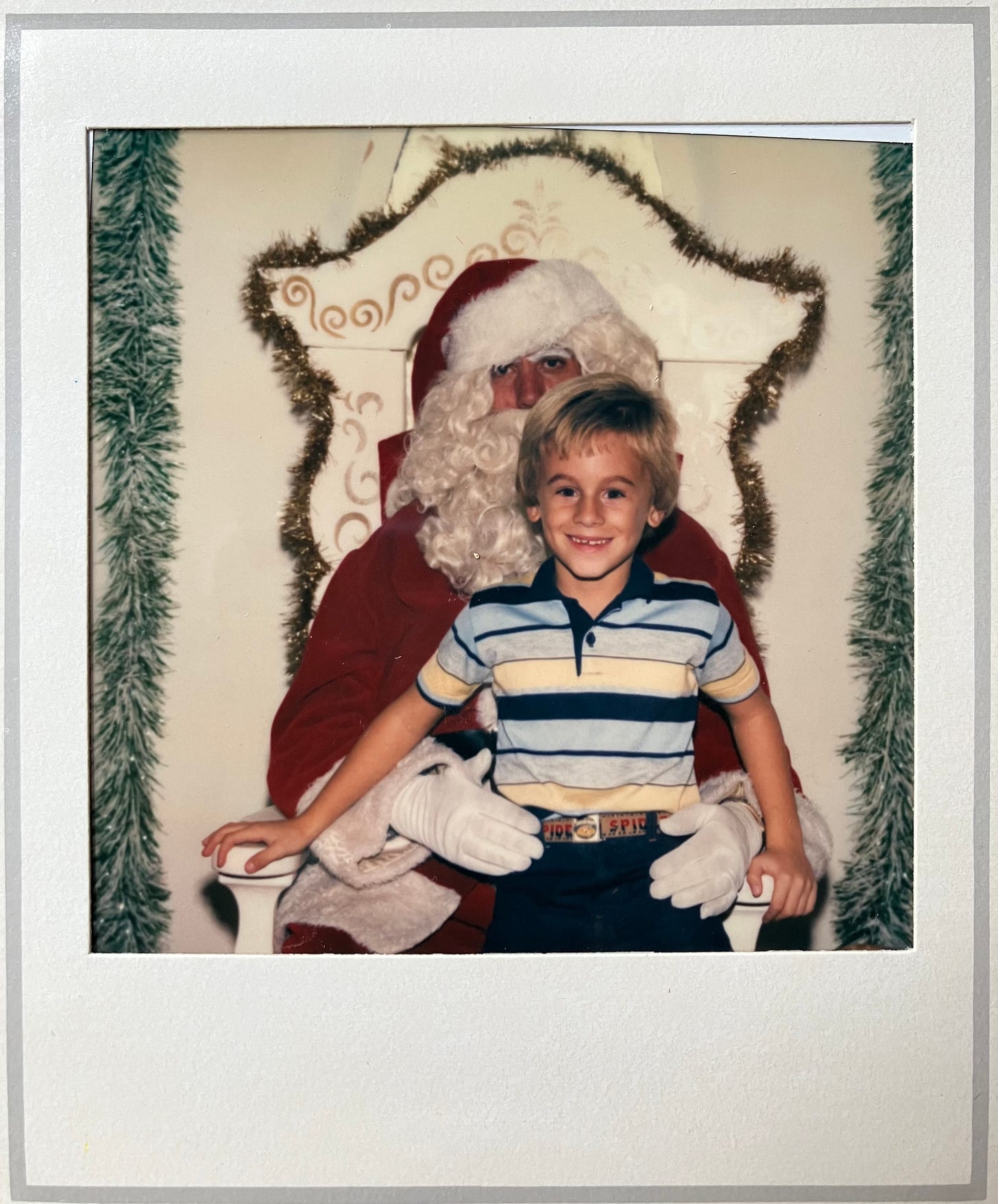

And every year, I took a photo with Santa at the mall.

It was safe enough to roam. I knew never to leave the mall without my dad. And there was always something new to see, and coins to toss in the fountain, and clothing racks to hide inside while watching adults that didn’t know I was there. When I walked through the open, indoor plaza where Santa Claus sat in a huge Styrofoam Wonderland, surrounded by polymer wads of fake snow while the sun shone outside, I had no idea that malls would ever be anything other than what they were right then, and that America would one day lose interest in them.

Of Phoenix’s many memorable malls, Los Arcos and Metrocenter were my favorites.

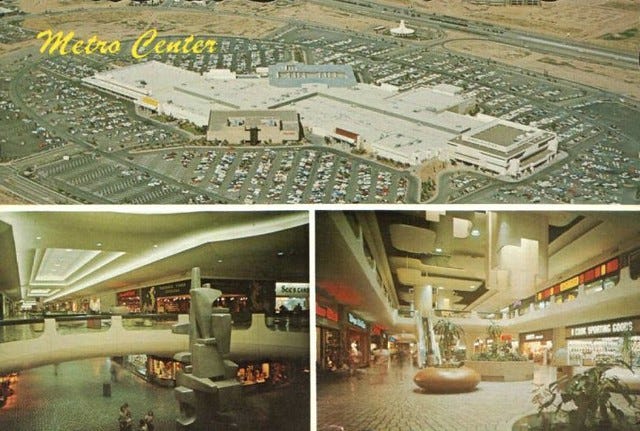

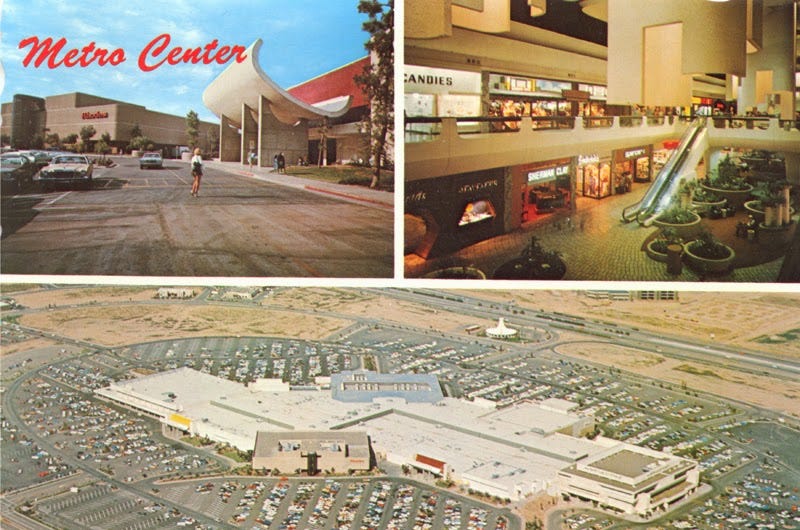

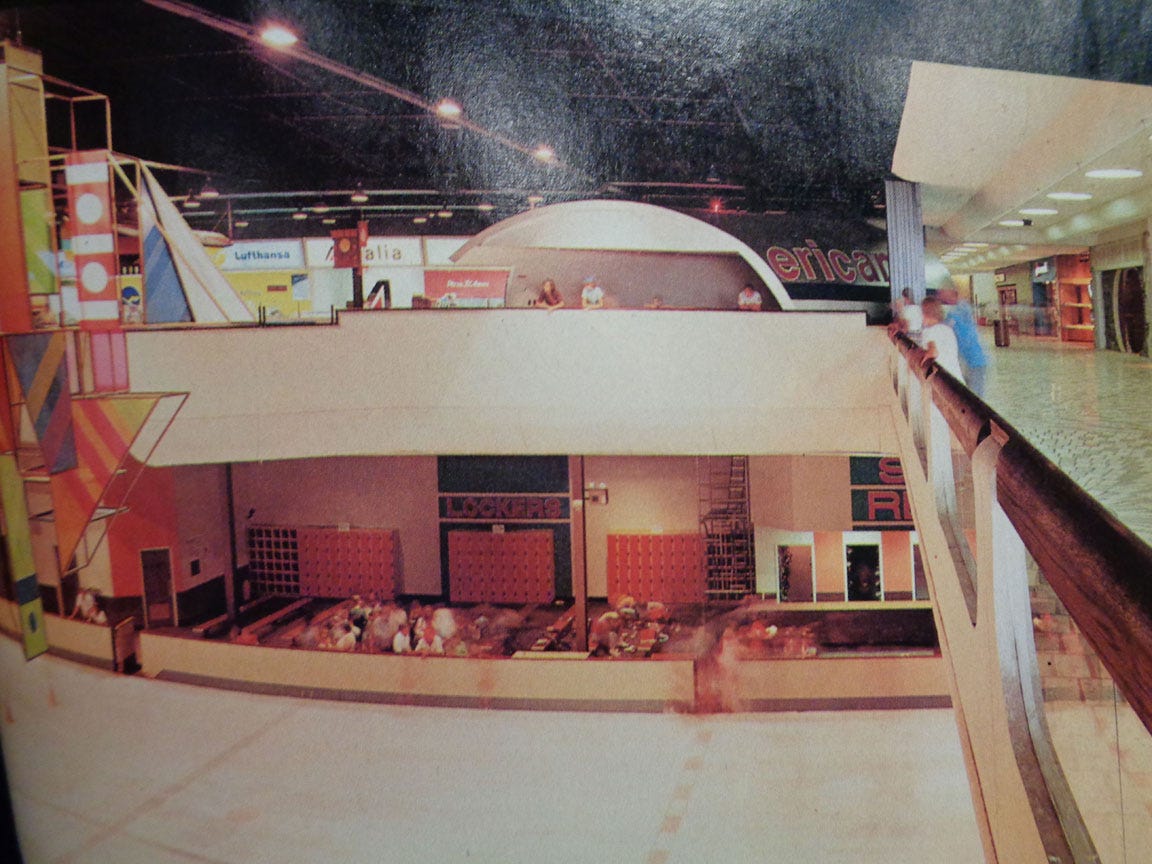

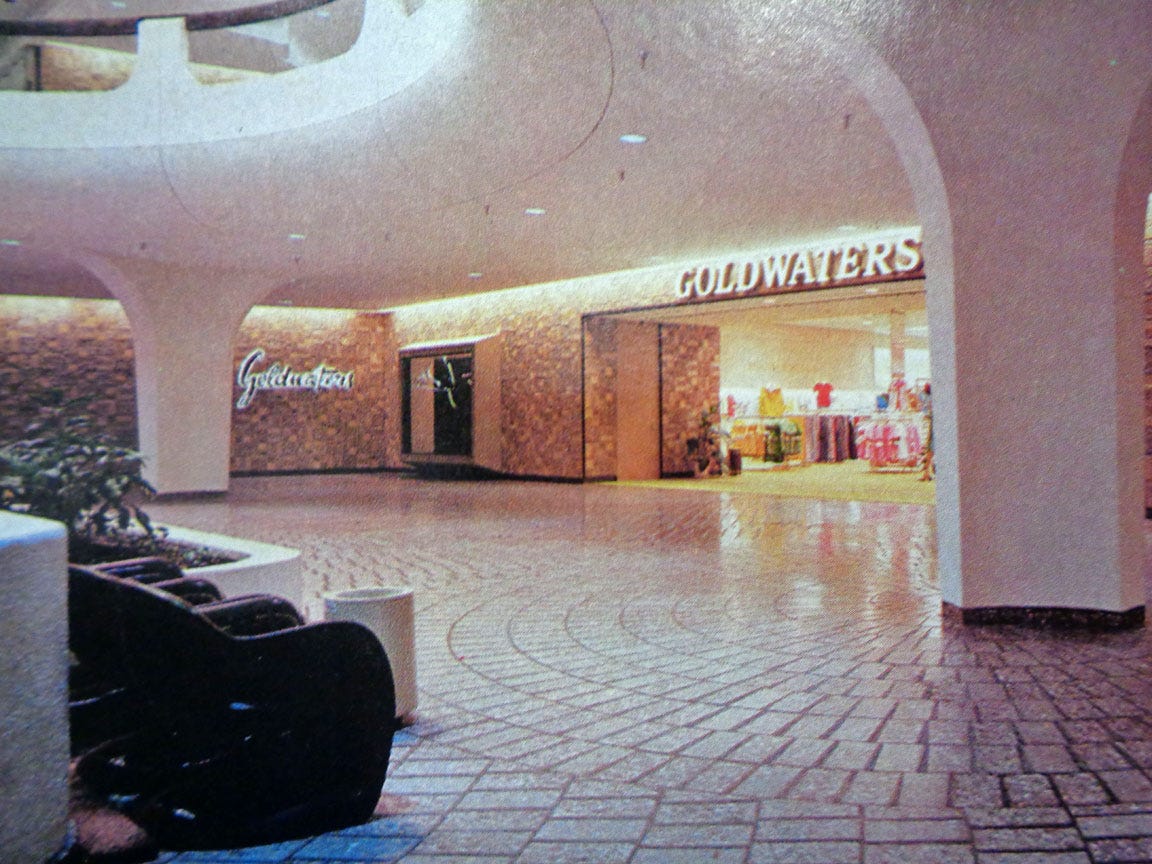

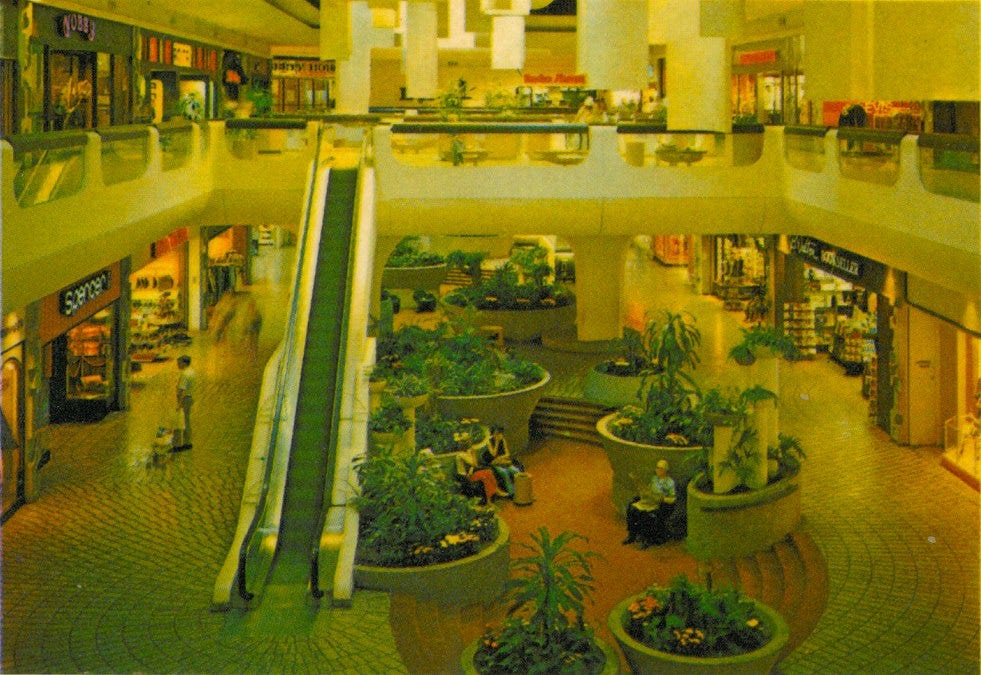

Metrocenter was massive. At over 1.4 million square feet, it was Arizona’s largest mall at the time and the state’s first two-story mall. Where most malls had one to three anchor stores, Metrocenter had five—Sears, Diamond’s, Goldwater’s, Rhodes Brothers, and The Broadway—and the $21 million dollar loan it received for construction was Arizona’s largest commercial loan at the time.

It had toy and hobby stores, a Spencer’s with all its adult-themed gifts, and it had a huge ice skating and giant video game arcade, all right by the food court.

In1988, Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure filmed scenes inside Metrocenter, with actors Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter eating in the food court by New Jade Chinese Food and riding the escalators I knew so well.

My mom loved to shop, so when she and I went there together, I’d often plan to meet her back at a certain place at a certain time, then I could disappear into the video game arcade and run around alone in Metrocenter’s sprawling corridors, watching my little feet bound over the brick floor’s intricate patterns.

It opened in 1973, and it looks like it now, but as a kid, its interior design motifs seemed futuristic and reminded me of Empire Strikes Back meets Danish modern. There was something about the balconies’ smooth white surfaces and cut-outs that looked like Cloud City. Lots of mallrats remember their favorite mall foods. I remember Metro’s architecture.

And the circular designs in the ceiling looked like spacecraft from Close Encounters of the Third Kind were about to land on you. Even Metrocenter’s elevator looked like a chute from a Star Wars space station.

But Metrocenter was on the other side of town from me. Los Arcos was literally a five-minute bike ride from home, so I went there a lot.

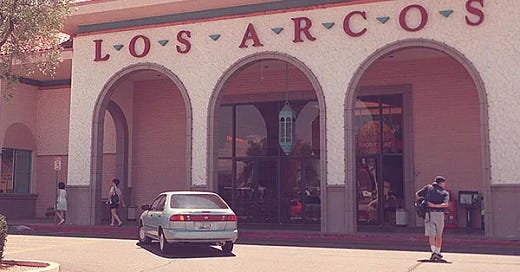

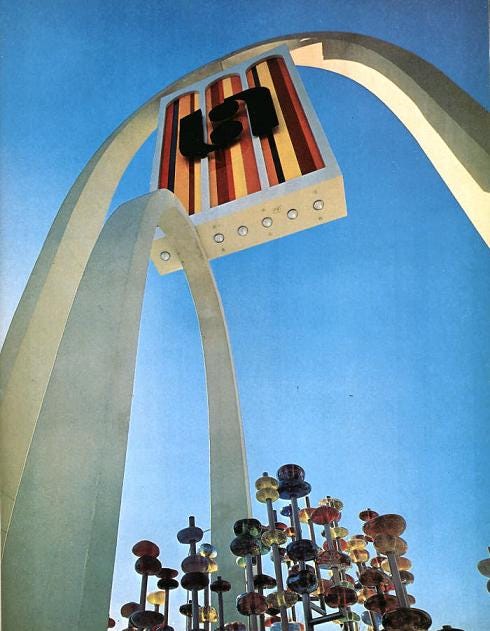

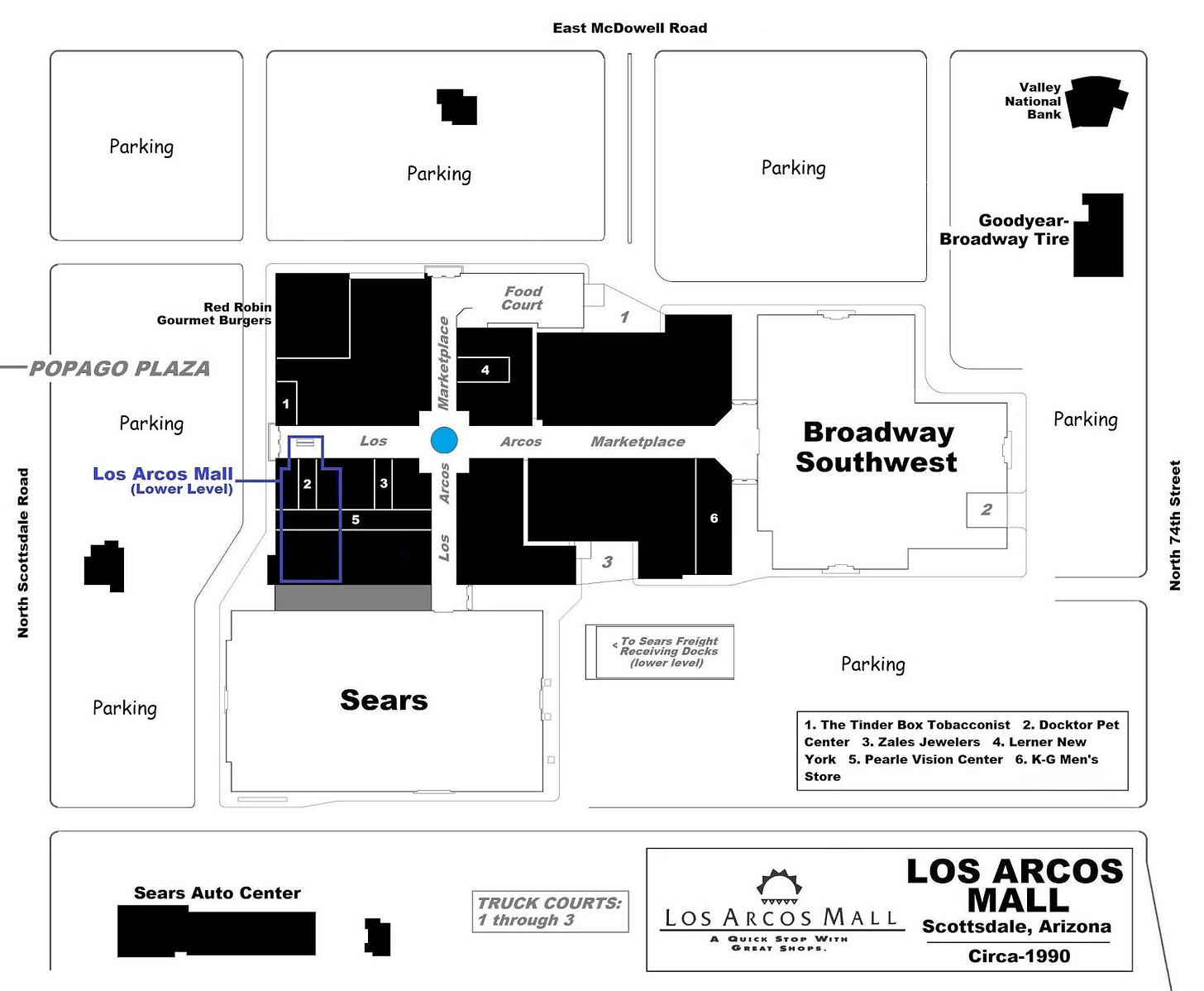

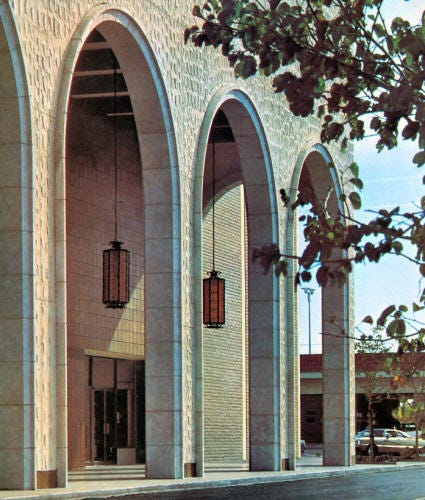

Located at the busy corner of Scottsdale and McDowell roads in what was once a cotton field, Los Arcos opened in 1969 and was a central feature in many south Scottsdale kids’ lives during the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. Translating as “The Arches,” passing cars were graced by the beautiful dual arched sign for three decades.

For those of us who grew up around here at that time, Los Arcos was the shit. It had Kay Bee Toys, Waldenbooks, briefly Sam Goody music, and a great pet store filled with critters upstairs.

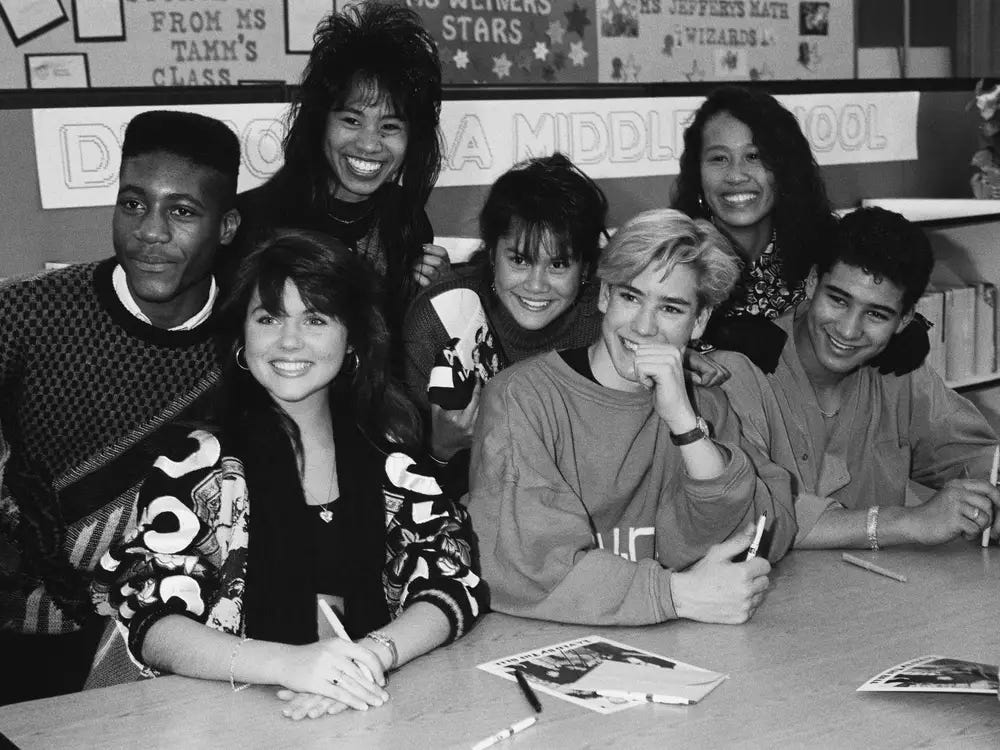

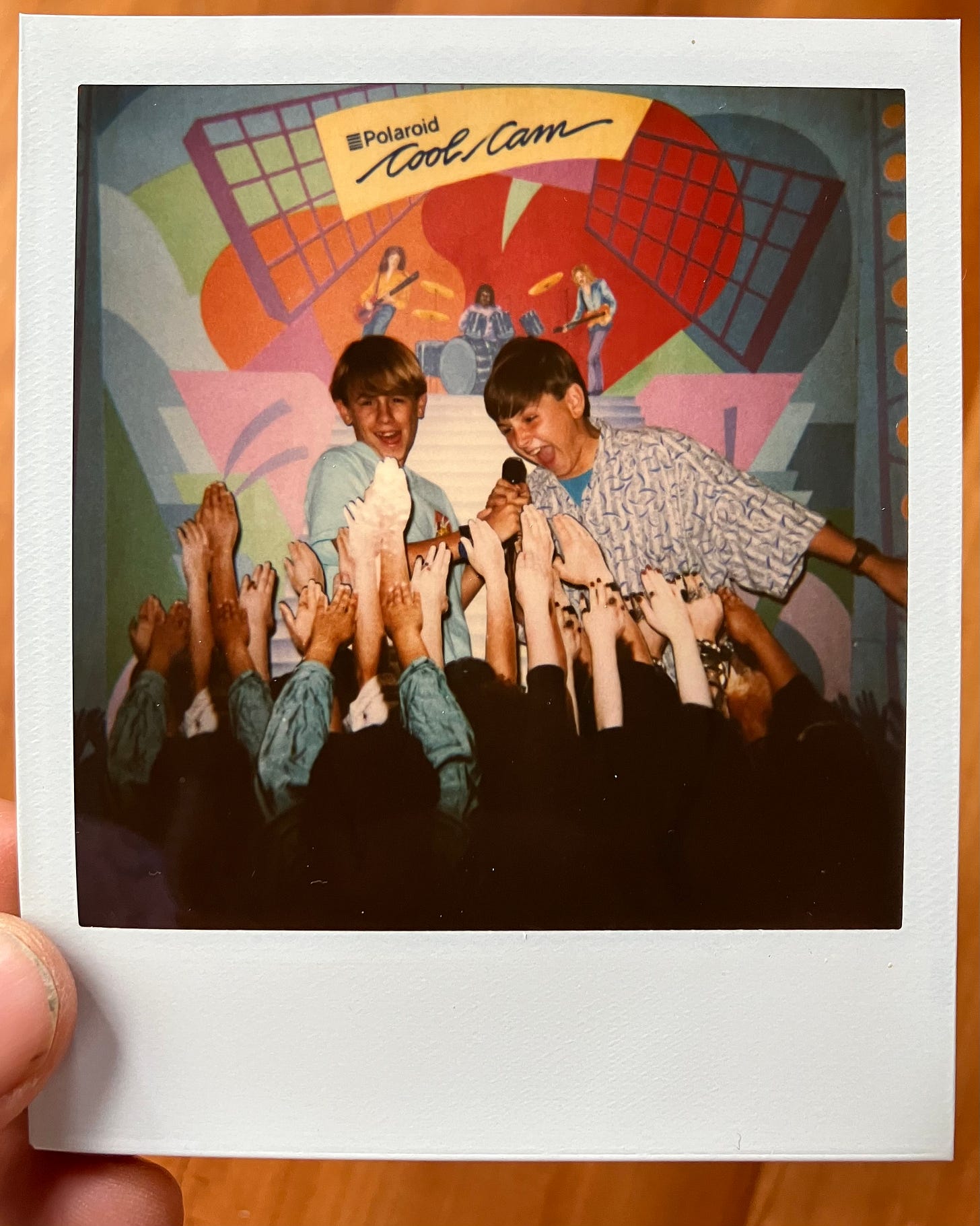

In the ’90s, malls would draw crowds by hosting pop bands to play inside, and even had TV stars do signings, like the case from Saved by the Bell.

Los Arcos didn’t do that. Instead, every Halloween, it set up incredible haunted houses in the parking lot, and speakers pumped up the jams to the terrified young crowd there, playing Salt N Peppa and whatever was new. The rest of the year, we came to eat.

Poncho’s Mexican buffet made all their food fresh, and it connected to the food court, whose center piece was, for me, the Orange Julius, and the photo booth.

David’s Deli was one of the best delis in town, so if you wanted something more urbane than a bacon cheeseburger at Red Robin on the mall’s northwest corner, you let the high school metalheads in Megadeth t-shirts make you a pastrami on rye.

On the other end of the mall was Luby’s Cafeteria. My parents took me there for budget dinners on some weeknights. The steamed white fish covered with lemon slivers was good. The mashed potatoes and gravy were passable, and I loved sitting in the vinyl booths with my folks, laughing and eating, but mostly, the place taught me the connection between soft foods and the elderly. I never went there myself.

Miller’s Outpost was a place to shop. The doorway to K-G Men’s Store was fun to hide in when you were playing hide and seek with your friends, unless a clerk told you to leave. Grumpy ladies ran the mall’s Hallmark store, so I was used to that, and the clerks who saw me reaching for porn mags on the high shelf at Waldenbooks always shot me looks. Radio Shack did its thing, and until it closed in the mid-80s, there was Hobo Joe’s restaurant was across the parking lot, which was a popular local diner chain that opened in the 1960s, and include a statue of the friendly Hobo Joe mascot, Arizona’s version of the Bob’s Big Boy mascot, but it always seemed like a place where old people smoked and drank coffee, so I never went in.

My thing was pets, toys, and arcade games.

Phoenix is not a city where you’ll find many basements, but Los Arcos had a Harkins movie theater and Superfun video arcade in the basement, which required you descend a narrow staircase lined with thick red carpet. At the end of the summer, to soften the approaching start of school, my dad would hand me a roll or two of quarters and say, “Go have fun.”

I played Tron, Joust, Q*bert, Star Wars games, and Outrun. I loved Outrun’s beach settings and soundtrack, especially the song “Passing Breeze.”

Even though it 607,000 square feet and had 73 stores, the mall was relatively small and simply laid out.

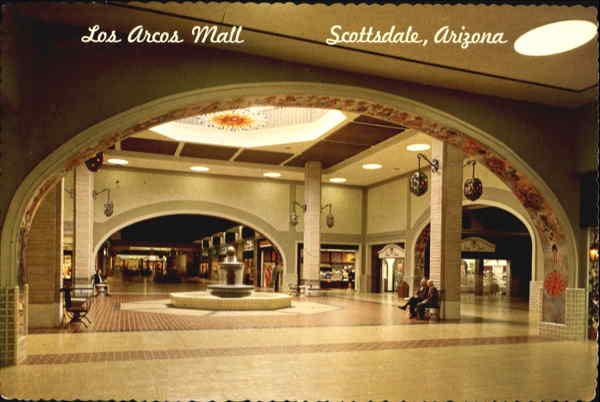

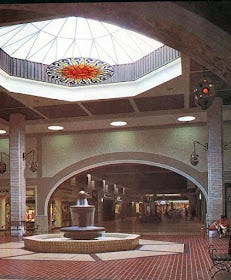

It was arranged as a cross, with two main corridors—or concourses—running perpendicular and intersecting in a sunny central courtyard with a fountain. This was the Center Court.

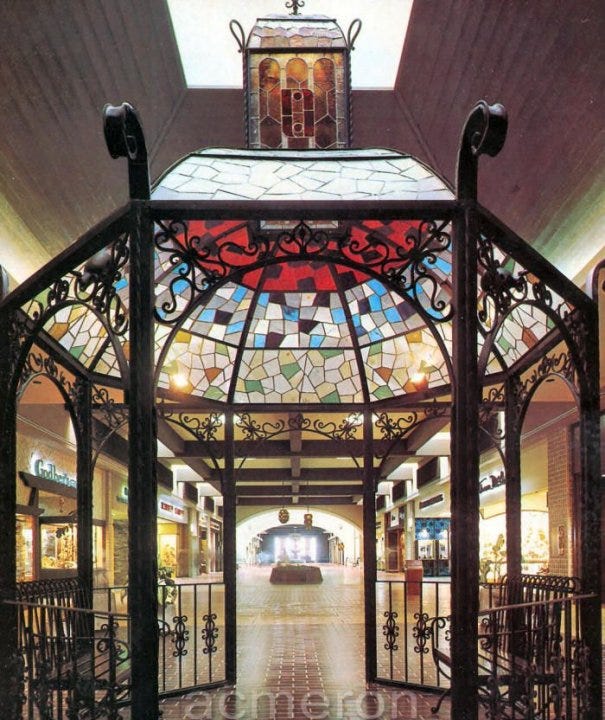

With a vaulted ceiling suspended by tall reaching columns, the Court was illuminated by a dome of glass, named the Center Court skylight, which itself was accented by a hanging pane of stained orange and yellow glass. It was beautiful. Malls had to be to pull shoppers inside from the sunny world outside. One of my favorite things about Los Arcos was the feeling of walking through this Center Court, and the way the sweeping tiled arches welcomed you in.

“Artisans from Guadalajara and Mexico City were hired to hand-craft various details,” wrote the Mall Hall of Fame website, “such as the stained-glass sunburst suspended inside this octagonal Center Court skylight.”

Los Arcos was also very pleasing architecturally. Unlike Metrocenter’s ’70s futurism and Chris-Town’s mid-century lavishness, Los Arcos was decorated in a grand, almost gaudy, Spanish Colonial style, with tiles, fountains, and ornate wrought iron light fixtures. The whole place had a yellow/orange/brown color scheme accented with wrought iron. Unlike the Center Court, the corridors were dark and cozy, making the mall feel like a giant Mexican food restaurant, more specifically, an extension of the Los Olivos restaurant, which opened in Scottsdale in 1947.

Yes, so much of my mall life happened in the late 1980s, but many of us Gen X teens peaked while living the ’90s mallrat lifestyle.

You didn’t have to be an Arizonan to love malls. Many Americans, from the Sunbelt to the Midwest, spent their childhoods in malls. It was the times. Before the internet stole most business away from brick-and-mortar stores, people shopped in malls. Us ’90s kids also ate, ran around, watched movies, played video games, and wasted time in malls, because we could roam them freely with our friends, unsupervised, we could entertain ourselves outside the house and our parents’ watchful eyes, and we could try to meet members of the opposite sex there. When our folks told us to turn off the TVs and get outside, we could just bike to the mall. If you grew up in the ’80s and early ’90s, you spent time in malls.

“Before the internet,” Business Insider wrote, “malls were the only place where you could get gadgets from Sharper Image, clothing from Limited Too, accessories from Claire's, and a sticky, delicious Cinnabon all in one place.”

South Scottsdale kids would stop at Los Arcos on their walks home from nearby Coronado High School. We biked and skated and rollerbladed and walked there from home, even when the temperature was over 100 degrees.

I didn’t realize people actually stole your bike until I locked my first bike outside the Broadway department store at Los Arcos, and my friends and I found it missing when we went to bike home. Thieves cut the chain lock. I had to walk back to my friend’s house to call my parents with the bad news!

For the institution of the mall, the late-80s marked the beginning of the end. By the 1990s, the market was saturated. Malls had multiplied so quickly that they cut into each other’s profits. The rise of the factory-outlet stores and large discount retailers such as Best Buy, Lowe’s, and Toys “R” Us (often known as “category killers”) lured customers away. Amazon’s low prices and online shopping in general put the nail in the coffin.

“The last new enclosed mall was built in 2006,” Smithsonian Magazine wrote. “2007 marked the first time since the 1950s that a new mall wasn't built in the United States. The 2008 recession was a gut-punch to already flailing mall systems: at a 1.1-million-square-foot mall in Charlotte, N.C., sales per square foot fell to $210, down from $288 in 2001 (anything below $250 per square foot is considered to be in imminent danger of failure). Between 2007 and 2009, 400 of America’s largest 2,000 malls closed. According to one retail consultant, within the next 15 to 20 years, half of America’s malls could die.”

Some malls died a predictable death.

Thomas Mall lost its anchors in the late eighties, was razed in 1993 and was replaced, in predictable fashion, by the modern version of the shopping mall: the “power center.” Target, Sears, IHOP, Applebee’s—out with the old and in with the new. Unlike its predecessor, a power center is a pragmatic, often bare-bones affair. It’s open-air, and is built around a vast, communal parking lot. Its central visual features are cars and pavement, which gives it more in common with a freeway than the Place Dauphine. Counter to Gruen’s original European vision of a mall as the social center of a community, neither the power center nor its simpler forebear, the strip mall, are places to stroll or have relaxed conversation over cups of coffee.

Other dead malls have enjoyed a strange afterlife.

The vacant husk of Maryvale Mall, in West Phoenix, was eventually converted into an unlikely amalgam that includes a middle and elementary school, community center, police substation, and a Wal-Mart. And some old malls have become purgatorial legends, like Dixie Square Mall, outside of Chicago, which opened in 1966, closed in 1978, and has stood dormant and decaying ever since. Its exposed corpse has attracted hordes of urban explorers and photographers.

Chris-Town’s demise was less dramatic. In a manner unbecoming a structure with three royal-sounding “courts,” portions of Chris-Town were demolished, and the leftovers grafted with a Wal-Mart, Costco, and Target. I am not alone in mourning the demise of what it represented. Victor Gruen, the mastermind of the mall, eventually moved back to Vienna, where he criticized American urban planning and the bastardization of his ideas. Southdale was a failure, he said, as was every mall that copied it thereafter. He called these monstrosities shopping machines, said they damaged the natural landscape, destroyed city centers, dissolved social connections, drove small merchants out of business, and, aesthetically, were marred by “the ugliness and discomfort of the land-wasting seas of parking” around them. It is an accurate description; we see these seas everywhere today.

Tri-City Mall: demolished in 1999.

Fiesta Mall: closed in 2018.

Metrocenter’s beloved Metro Ice Palace closed on March 18, 1990. And after various renovations, the mall itself closed for business on June 30, 2020. Many people documented its vacant interior before the doors permanently shut.

In 2020, The New York Times told Metrocenter’s story in order to tell the story of America’s dead malls:

Erik Pierson, 39, a dead malls enthusiast in Arizona, went to the first auction preview and plans to attend more, though he has not placed a bid yet. Mostly he has enjoyed the experience of seeing the mall in its final, uncanny form.

“I went there as a kid and obviously I’ve covered it quite a bit on my YouTube channel,” he said. “But that was the first time that I had been in it since it was closed. And it was bizarre. It was kind of bittersweet because I love that mall.”

Some people remember the ice-skating rink. Others remember the huge fountain that did timed shows, spitting water up and up, as high as the second floor, before it came crashing down onto tile with loud splats. The fountain was covered years ago.

“I think a lot of people just forgot about it,” Pierson told The Times. “And now it’s gone.”

Los Arcos died more quickly.

By the mid-90s, competing local malls—like Fiesta Mall and the nearby fancy Fashion Square Mall—and new commercial suburban “super centers” undermined the Los Arcos’ health, and as foot traffic thinned, its stores closed, and Los Arcos eventually did, too.

In 2000, it got demolished. The lot sat vacant for over five years as developers, voters, and local officials debated what to do with it. In 2008, the growing Arizona State University universe opened its SkySong Innovation Center, whatever that is, on the property.

When I moved back to Phoenix after seven years gone, the city had changed dramatically, but Los Arcos shocked me the most. It was gone. A vacant gravel lot stood in its place. I was 33 years old but wanted to cry. My dad said that ASU was “putting up some fancy satellite campus there or something.”

Rather than fading into the past, this piece of my childhood had been demolished. It was one of the first times something so central to my childhood had been erased, and even though I didn’t know it then, it was the first of many painful aspects of middle age that awaited me, and an introduction to the seductive power of nostalgia.

Walking down memory lane has some benefits, but nostalgia also formed the basis of so many mind-numbing, go-nowhere stories whose myopia felt like the cul-de-sacs so many Phoenicians grew up on.

When I mentioned Los Arcos to other locals, people perked up. “Oh my god,” they’d say, “I miss that place!” And: “My best childhood days were spent there.”

That’s how it goes.

My dad experienced the same sad hollow feeling when he visited his childhood town in southeastern Oklahoma once. “It was all gone,” he told me. “I shouldn’t have gone.”

Looking at ASU’s Innovation Center there, you’d never imagine what was once there, and all the childhood moments that weirdly dark mall facilitated.

Seen this ? https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100057714877596&mibextid=LQQJ4d

your mall has a facebook!

That was the greatest article ever written

Aaron! This was a fantastic read. I loved getting to experience the malls of your childhood. Richardson Square was the closest, and Prestonwood had the skating rink, but the real gem was Northpark, an architectural marvel like the ones you shared. Yes, it had stores, but it also had that 60's architecture I loved, gardens, modern art, sculptures, and air conditioning. It was Dallas, Texas! Too hot to be anywhere else. A scene of True Stories was shot there, too, the same mall where my grandparents mall-walked in the mornings in their later years. Thanks for jogging my mall memories.