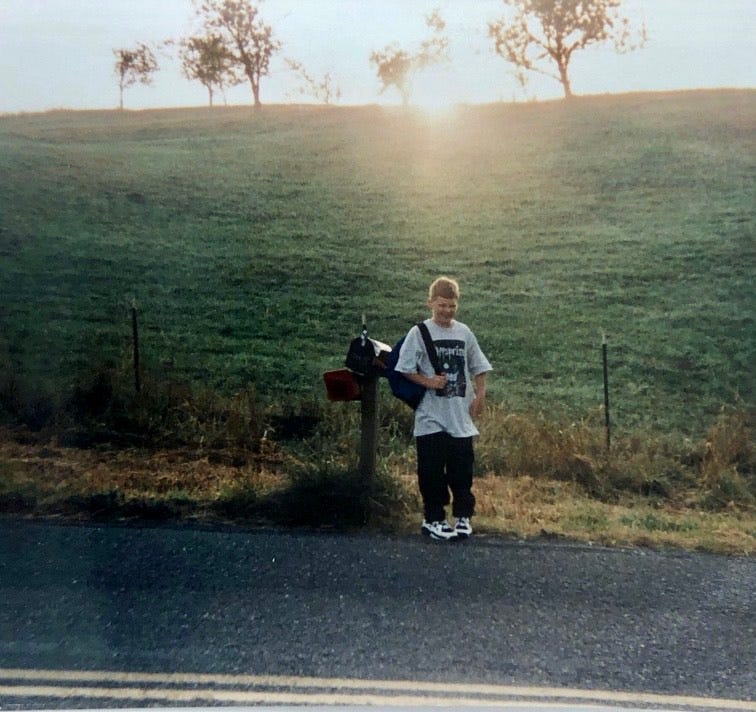

It’s hard for me to believe now, and it feels almost ridiculous to say, but there was a time when I firmly believed in alternative rock. At least in the early years of the 1990s, I believed it held some key to life that I, at that point in my development—as a painfully shy, rural American, preteen white boy, living in a trailer in the Pacific Northwest—did not have. I believed that by loving it, I would create points of connection with other alternative music fans or learn ways to connect through the lyrics—lyrics written by songwriters who often seemed to feel a similar disconnection and shyness but had somehow learned to overcome it, at least enough to sing songs in front of other people. And by loving it, I would be loved.

What “it” was, though, I could not say. The loose confluence of sounds that were termed alternative left few clues. While I could identify punk by its speed or particular vocal snarl, hip-hop by its breakbeat, and country by its twang, alternative had no center-of-Venn-diagram characteristic I could find. Sometimes I thought it was guitars, since most alternative bands relied on guitars, but some musicians like Björk, Morphine, and Tori Amos used them sparsely, if at all. And even if I decided to write off those as not truly alternative, the ways guitars were used by other alternative acts ranged too wildly—from acoustic fingerpicking to effects-laden walls of noise—to be helpful in puzzling out a definition.

Was it simply race—or, to be exact, whiteness—that defined the genre? At times that seemed possible, since most alternative bands were white-fronted, but, again, even by 1993, the year I began my process of immersion, there were a number of bands on my radar who weren’t white-led—bands like Shonen Knife, Rage Against the Machine, Blonde Redhead, The Veldt, and Cornershop—and a handful of prominent alternative bands like Soundgarden, Gin Blossoms, and The Smashing Pumpkins had at least one person of color in the band.

While people often called alternative music alternative rock, many alternative bands didn’t play rock at all, opting for something I couldn’t define. The aforementioned artists who didn’t rely on guitars, sure, but also genre-hopping, near-comedy bands like They Might Be Giants and Ween; the noisy, largely acoustic lo-fi artists like Daniel Johnston and Sentridoh; and the bands like Stereolab and Luscious Jackson who I found intriguing but uncategorizable.

The previous year, radio singles like PJ Harvey’s “Dress” and Frente!’s acoustic cover of New Order’s “Bizarre Love Triangle” had entranced me, in part because I could find no easy comparisons, no tidy genre placement, and generally had no language for what they were doing. But I was told that both the blues-tinged, punk-inspired “Dress” and the sparse and straightforward “Bizarre Love Triangle” were alternative music.

It was confusing! But also thrilling. And despite its absurd expansiveness, I still believed alternative was not just an alternative to the mainstream but an actual genre, and I was certain this genre was unequivocally good.

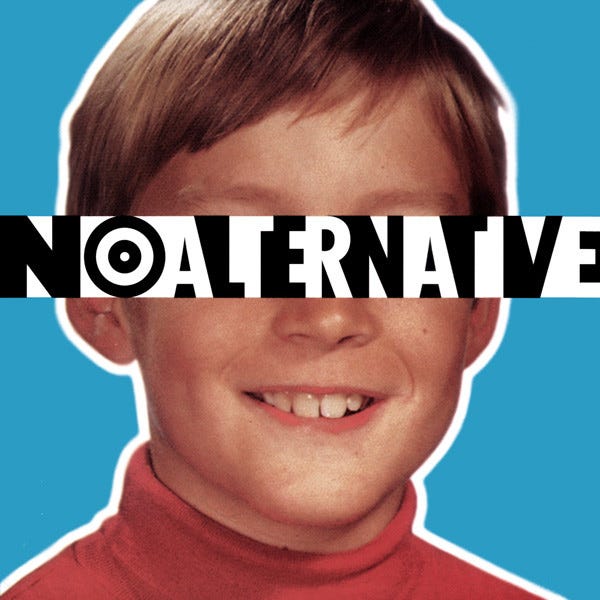

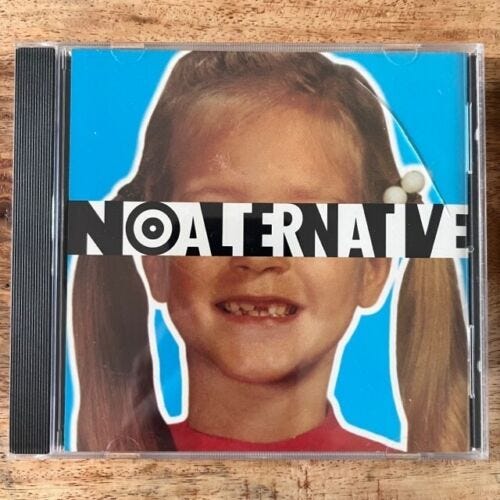

Then, just before Halloween, 1993, a compilation came out that I imagined would clear up all of my previous confusions. Its image grabbed me before I even knew what it was—an ad in Rolling Stone or Spin, I believe, maybe even a full page. A boy, probably around my age, with a ’70s mop and turtleneck, his eyes masked out by a block of black-and-white letters that spelled out NO ALTERNATIVE. I soon learned this was a compilation, an HIV/AIDS advocacy benefit, that there were multiple versions of the cover, a cassette version with additional tracks, extensive broadside-like liner notes, accompanying short films—it was seemingly as much art project as album. MTV declared a “No Alternative Week,” six days of programming that ended on the seventh with an hour-long special of music videos, live performances, spoken-word pieces, collaged video-art shorts, HIV/AIDS PSAs, and teens speaking frankly about sex. Clearly, this was a big deal.

A few months later, in early 1994, I was finally able to buy No Alternative using my mom’s “10 CDs for a penny” deal from the BMG mail-order company. I was 11-and-a-half years old, and this was my first alternative rock compilation. Until then, I’d mostly listened to the Seattle radio stations and watched MTV. My mom, my mom’s boyfriend, and my uncle who helped raise me, were all music obsessed, so I soaked up what they listened to—my uncle’s love of The Beatles and ‘70s hard funk, my mom’s adoration of soul music and Jimi Hendrix, her boyfriend’s endless Frank Zappa live bootlegs—and, maybe because of this, I hadn’t had much need or desire to develop my own musical tastes. Up until No Alternative, my mom and I had purchased new tapes and CDs together. We’d usually agreed on what that album should be. Whether it was Melissa Etheridge, Counting Crows, or Nirvana, they were albums that interested us both, and none of them were “my” CDs.

My mom liked the Seattle scene emerging 40 minutes from our rural Washington outpost, as well as select alternative rock songs that popped up on the radio. But she wasn’t especially interested in digging through an alternative compilation to try to find a new favorite band and, all of a sudden, I was. So the album serves as a mile marker in my memoir in music: the moment my tastes diverged from the adults around me.

More broadly, though, No Alternative marks what I see as the beginning of a cultural shift. While the undeniable weight of Nirvana’s Nevermind almost exactly two years prior was one major catalyst, No Alternative has always felt like the turning point, the place where alternative music changed, where coverage around the AIDS crisis ever-so-slightly evolved, where do-it-yourself strategies of political fundraising started being used on a larger scale, and the place where the disaffected machismo of underground rock scenes intersected with queers and feminists.

Another reason No Alternative signals a turning point to me is how immediately dated the compilation became. For the album’s 20th-anniversary piece on Stereogum, Michael Nelson wrote, “If you were around at the time of its release, you’re almost certainly familiar with the CD’s striking cover (two versions of which were available, boy and/or girl), if not at least a handful of the songs included therein. Furthermore, there’s a pretty good chance you haven’t heard or even thought about most of those songs—say, Soul Asylum’s cover of ‘Sexual Healing’—in at least 19 years.”

I think he has a point, especially regarding his math. If Nelson’s right that most No Alternative listeners spent at most a year with the compilation before moving on to other things, that’s because what came out under the broad banner of alternative music and culture in the 12 months following No Alternative’s release was so earth-shaking.

Think about this: Three months after No Alternative, Green Day released their mainstream breakthrough Dookie one day in February, then Pavement released their indie-scene masterwork, Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, a couple weeks later. A few days later, Reality Bites opened in theaters, establishing the slacker movie—and, by extension, what was thought of as the alternative-rock lifestyle—as a mainstream genre, while also making Lisa Loeb the first unsigned artist in history to have a Billboard number one song. Two weeks after that, Beck broke into the mainstream with his album Mellow Gold and “Loser” became a cultural anthem. The week after, Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral was released on the same day as Soundgarden’s Superunknown—albums that made these already popular bands into full-blown stars. Exactly a month later, Kurt Cobain was found dead. The Offspring’s breakthrough, Smash, was released three days later, and Hole’s breakthrough, Live Through This, four days after that. Less than a month later, Weezer’s debut made nerd-rock its own musical subgenre and particular way to slack. No Alternative had been out for only six months, and already everything in the alternative rock world was completely different.

In the next six months, Oasis, Veruca Salt, Soul Coughing, Bush, Sunny Day Real Estate, Jeff Buckley, The Halo Benders, Shellac, and Elliott Smith released their debut albums. Long-running underground heroes like Meat Puppets, Dinosaur Jr., and Guided by Voices broke through to the mainstream for the first time. And all over the alternative map, artists were putting out albums that redefined their sound and image—Sonic Youth, Liz Phair, Ween, The Cranberries, Sebadoh, Sugar, Lush, Beastie Boys, R.E.M., The Melvins, Blur, Alice in Chains, Ani Difranco, Rollins Band, Superchunk, Stone Temple Pilots, The Stone Roses, Built to Spill, Shudder to Think, and Tori Amos all released career-changing records. That same period saw the adult-alternative subgenre reaching new heights of success, with the understandably forgotten album Throwing Copper by Live (which outsold almost all of the aforementioned albums) and Hootie and the Blowfish’s wildly successful Cracked Rear View (which sold 20 times of most of the aforementioned albums).

The ultimate beloved alternative-era TV drama, My So-Called Life, debuted on network television that fall and, perhaps appropriately, on the one-year anniversary of No Alternative, Kevin Smith’s low-budget debut film Clerks was released, its surprise success helping to open opportunities for indie filmmakers for years to come, and furthering the slacker genre’s brief reign. By the time Nirvana’s massively successful posthumous release, MTV Unplugged in New York, came out a week later, No Alternative was firmly a relic of the past. In a year’s time, a different era had begun.

When looking at the alternative genre—which was really just an umbrella term to hold a lot of new sub-genres that corporate America and the majority of music listeners didn’t know how to make sense of—there’s perhaps no better place to view what came before and what came after than No Alternative.

While most people seemed to read No Alternative as a big-budget compilation put together by industry insiders with connections, this was only part of the story. It was the third compilation from the Red Hot organization, an HIV/AIDs advocacy non-profit that used music to spread awareness and try to dissolve common stigmas. The profit from their CD sales and royalties went to a variety of organizations doing hands-on work in communities, advocating to change public policy, forward research, and support queer people (including groups like ACT UP, AmFAR, and T.A.G.). Their first two compilations had been aimed at far different audiences—a technique the organization has seemingly used across to their now-30+ compilations to bring new people to their message with each release—with 1990’s Red Hot + Blue, a tribute to early twentieth century American songwriter Cole Porter, and 1992’s Red Hot + Dance, a club-inspired compilation led by a George Michael hit.

But while No Alternative had the backing of an organization who had the connections necessary to bring it to a wide audience, it was largely compiled by a few inspired college students. Over the course of two years, Paul Heck, Chris Mundy, and Jessica Kowal gathered previously unreleased tracks—a number of them written specifically for the compilation—from twenty-one artists.

“I was just a kid in New York who was a music fan,” Heck said in a 20-year anniversary interview with Radio New Zealand. “I would go see the bands every time they came to New York and personally go up to them and be like, ‘Hi, I’m making a record. Would you guys be on it?’”

The album’s title was meant to work on a few different levels. It signaled that the AIDS crisis was something that could no longer be ignored, it was a poke at Margaret Thatcher’s infamous “there is no alternative” pro-globalization position on market economies, and it was a questioning of the genre label as a whole. But by the time the compilation was in production, one of those levels—according to Heck—was the fact that these so-called alternative bands were becoming the hit-makers of the day and were no longer the alternative to the mainstream. They were the mainstream itself.

I think it’s important that No Alternative was decidedly not an indie-rock compilation, even if some of its most lasting tracks were from indie bands. Like its parent organization, the compilation was interested in pushing into the mainstream, knowing that HIV/AIDS research and awareness was more important than any indie cool cred. But particularly with No Alternative, the curators seemed to be offering a challenge to the alternative scene as a whole: You’ve got everyone’s attention. What can you do with that?

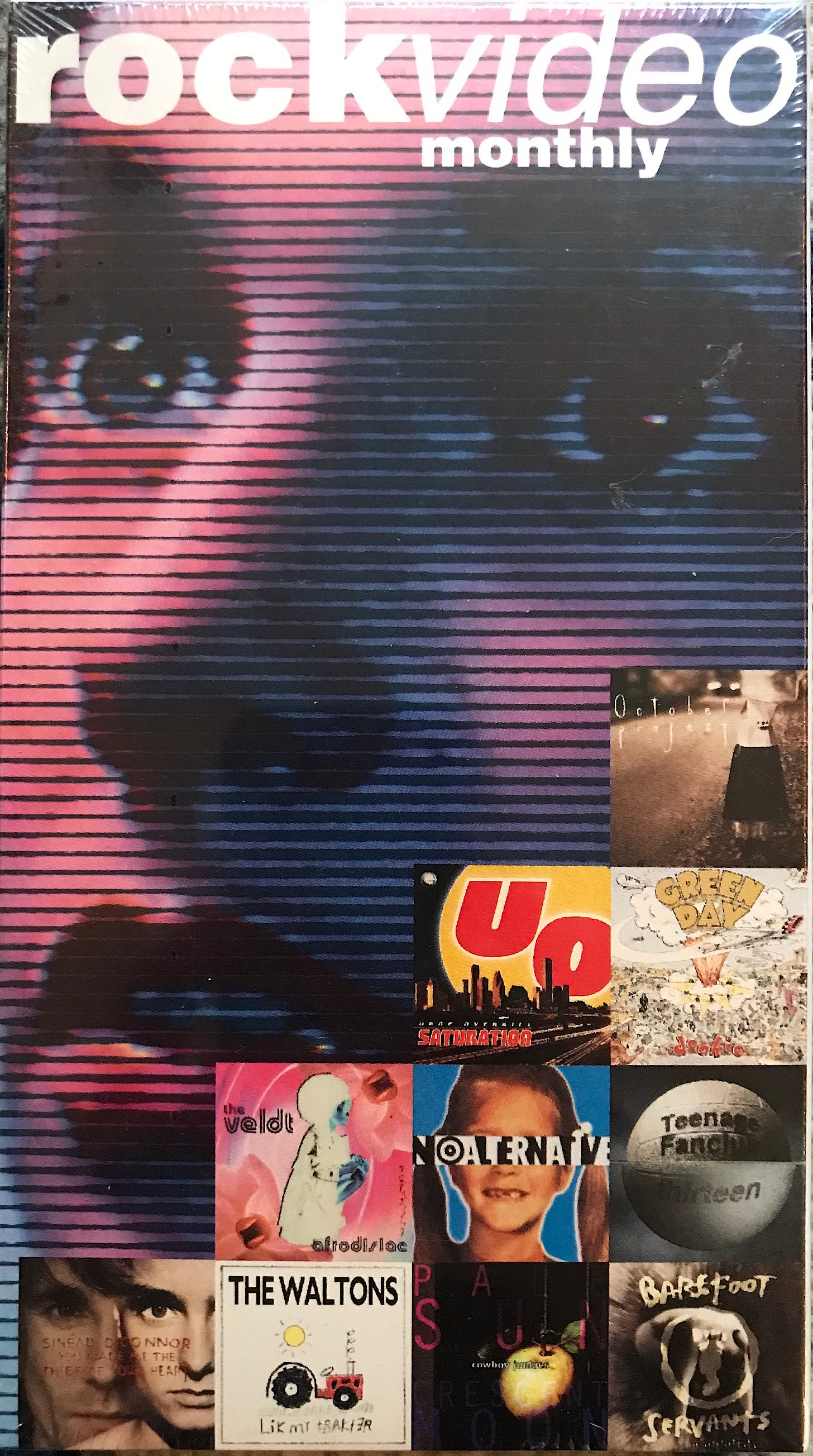

No Alternative’s legacy—at least in terms of how nostalgic people like me are about it—is maybe mostly due to good design. It’s also due to how impressive the compilation’s track listing appears and how, up until that point, alternative compilations didn’t have the same finger on the pulse.

Comps that included alternative bands were already becoming part of the culture then, if mostly by way of soundtracks, but neither Pump Up the Volume’s eclectic pirate-radio-esque assortment or Singles’ loose take on the grunge scene were actually advertising themselves as alternative. Most non-soundtrack comps that attempted that advertising were hilariously clueless, like 1991’s widely marketed Theodore: An Alternative Music Sampler that lumped Kate Bush, Social Distortion, Public Enemy, and Indigo Girls together.

While the compilations released in 1993 were getting closer to the direction the term ‘alternative’ was headed, and even the possibilities of the alternative comp-as-fundraiser—the Sweet Relief benefit for singer-songwriter Victoria Williams’ multiple-sclerosis treatments came out a few months prior, and Born to Choose, a pro-choice and anti-rape advocacy benefit, released the same day as No Alternative—No Alternative ended up reaching the furthest.

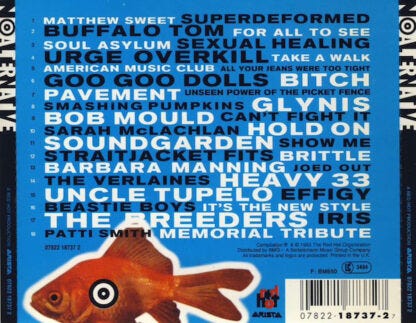

Regardless of how I think No Alternative plays as a whole, the curators did a great job capturing where things were at. The comp had alternative groups that had recently become mainstream, like Smashing Pumpkins, Soundgarden, Soul Asylum, and (in the hidden-track slot) Nirvana. Alternative groups that were a year or two off from becoming mainstream pop groups and losing their former edge, like Goo Goo Dolls, Urge Overkill, and Sarah McLachlan. There were some forerunners to ’90s alternative—some great aunts and uncles, if you will—such as Patti Smith, Bob Mould, Sonic Youth, The Verlaines, The Beastie Boys, and Jonathan Richman. And there were the alternative groups that most often got couched as college rock, like Pavement, The Breeders, Buffalo Tom, American Music Club, Matthew Sweet, Uncle Tupelo, Straightjacket Fits, and Barbara Manning & the SF Seals.

The fact that every group contributed a previously unreleased track—many, according to No Alternative compiler Paul Heck, wrote songs specifically for the compilation—feels like an astounding feat, especially at a moment when so many of the groups were getting flooded with more attention than they were previously used to.

I loved that its popularity made compilations a far more viable industry. In the months and years that followed, I bought countless alternative compilations. Like most preteens, I was on a limited budget—I got a five dollar allowance each week and had a couple low-paying lawn-mowing jobs—so I had to be careful with my music purchases and compilations were cheap, often being a small fraction of the typical $16.98 price tag that most CDs carried in the mid-’90s. Living in an age where we couldn’t stream, each purchase was a risk. Beyond singles on the radio and MTV, the only way to preview an album was at a listening station at a record store. The small-town record store nearest to us didn’t have one and the store in the closest mall mostly had albums I was uninterested in on their listening station. A couple times a year, I could convince my mom to use her one day off for a Sunday day trip to Seattle, and I would hit the record stores I knew about—Cellophane Square, Tower Records, the Sub Pop Megastore—listening to any of the sample songs I could, reading every staff review, trying to soak up as much as possible until my next opportunity.

Compilations were less of a risk, because there was a better chance that I would like something. There were a number of CDs I’d purchased based solely on a magazine or zine review that I ended up not liking at all. But, like many low-income kids in the ‘90s who were taking similar risks in the sudden deluge of musical artists and options, I would be stuck listening to it over and over, trying to get my money’s worth, hoping it would eventually grow on me. But even the worst, most poorly imagined and sequenced compilations had at least one song I liked.

Even if no one I knew still listened to No Alternative by the end of 1994, it lingered in collections for years to come. As a person who, upon entering someone’s home or room, gravitates immediately to bookshelves and music collections, I saw it on dozens of wall racks and in messy CD and cassette stacks throughout high school. Each time it was a nice surprise, and the compilation opener, “Superdeformed”—Matthew Sweet’s attempt at being dangerous and heavy instead of that moment’s golden boy of power-pop—would run through my head. Seeing it felt like nodding to an old friend, someone you didn’t have much in common with anymore but who had helped you become the person you became.

Terrific read about an album I thought no one else cared about but me. Believe it or not, I still listen to it from time to time and it never fails to bring me back to the days when I was listening to it with fresh ears and tons of excitement. I appreciate your take (and questions) about the alternative genre at the time. I remember those days well and tend to agree with your description of the sound and the fact that no one really knew how to describe a good chunk of the music being made then.