Pearl Jam, Nirvana, and Trying to Capture Magic

No recordings can preserve the experience of a killer concert, but at least they help you remember.

As usual, it was a person, not MTV or Rolling Stone, who tipped us off to my next favorite band: Pearl Jam. Her name was Jessica. She and our friend Jason were dating.

Jessica had joined Mother Love Bone’s badly named Earth Affair fan club, but after the band dissolved in 1990, she signed onto their new band’s fan club, called the Pearl Jam Ten Club. The promotional machinery had clued her into about Pearl Jam’s major label debut, Ten, before it even came out, and it clued her in about their supporting tour. Then she clued us in.

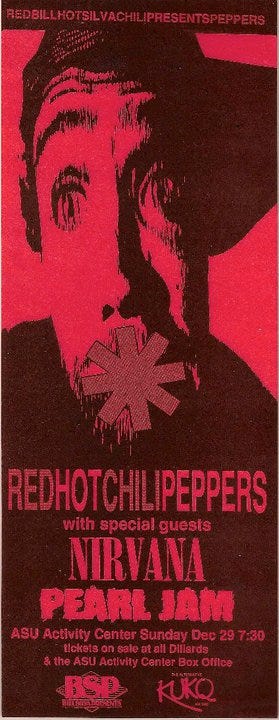

My friends and I went over to her mom’s apartment one day. It stood near the string of public parks that we’d been riding our bikes through for years, first just to play as kids, later as teenagers riding to record stores and video arcades. Bright Arizona sunlight flooded Jessica’s living room, and she explained how in December, Love Bone’s new band was opening for Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers at ASU Activity Center. “They will blow you away,” she said. We already loved Nirvana’s Bleach and had just started digging their new catchy one Nevermind. It came out in September. We’d grown up listening to the Chili Peppers, whose whole “me and my friends” deep brotherly love thing resonated with our tight male friend group, although their spazztic brand of sexist, white boy funk-rap quickly ruined the band for me.

On this day, Jessica played us Ten. After the weird, almost New Agey intro music, the song “Once” blasted through her mother’s speakers. First came the guitar riff—just by itself. Then the drums and bass locked the band into a raucous jam. “I admit it,” the singer snarled, “what’s to say?” At the time, fluff like Michael Bolton poured out of mall and car stereo speakers everywhere you went. “Once” was a revelation. We were rapt.

Song after memorable song hammered us like that. The front-man sang with the kind of seductive urgency that appeals to raging teenagers. The two guitarists wove together their solos and pounded out powerful riffs like the one on my instant favorite song, “Deep.” Ten was rocking, catchy, angry, and fresh. It was more aggressive vocally than Andrew Wood’s Love Bone, less playful, but also less corny than Wood’s occasionally cringe-worthy metal lines like “I need your smooth dog lovin’, oh yeah.”

It’s easy to think Pearl Jam’s first single “Alive” as the song that launched their career. But as the first song on Ten, “Once” was many listeners’ introduction, so for me, “Once” was this band.

Apparently we’d missed Pearl Jam two months earlier on their first tour, when they played Phoenix’s tiny metal venue The Mason Jar. ASU Activity Center wasn’t the intimate club setting that Sub Pop’s highly curated photography had started marketing as the face of the new rock ‘n’ roll. It wasn’t the gorgeous Moore Theater in Pearl Jam’s “Even Flow” video, which would appear in 1992, where singer Eddie Vedder drops from the balcony onto the crowds’ outstretched like a fallen angel. ASU Activity Center was a big cavernous sports venue located on a university campus. It didn’t have character. But it was as cool as a band’s presence made it, and Nirvana was the coolest band in the fall of ’91.

My friends had seen Jane’s Addiction play the ASU Activity Center in January, 11 months earlier. My parents wouldn’t let me go because it was a school night, and I had homework to do. My loving folks were so generous in many ways that I only faintly resented them for this. But as I sat on my bed, reading school books that night, my digital bedside clock clicked to 9 p.m., I pictured my friends jumping around in the pit as Dave Navarro wailed on his guitar in front of them, wearing his signature sunglasses and surrounded by smoke machine fog. Bastards, I thought. At least I got a flyer.

We bought the Nirvana-Pearl Jam tickets immediately. Only nose bleed seats were left.

At the time, I didn’t know Pearl Jam’s story. Their story is this: After Mother Love Bone’s singer Andrew Wood died in March 1990, his friends wondered what to do. They were distraught. Of course, the record company was disappointed, too. PolyGram had invested a lot of money and hope in Love Bone’s success. Wood’s friends like Chris Cornell and Love Bone guitarist Stone Gossard grieved by playing music. “I had the personality type that said ‘Let’s just keep going,’” Gossard said.

One night, Gossard and KISW disc jockey Damon Stewart were having beers at the Oxford Tavern near Pike Place Market. Stewart hosted the “New Music Hour” show and asked Gossard what he was up to. “He said he was doing a little writing,” Stewart remembered, “just noodling around.” When they went outside to hit another bar, they ran into local guitarist Mike McCready. He and Gossard had known each other since middle school, when they’d traded photos of rock bands they liked with each other. McCready’s hairband Shadow had failed to get a record deal in LA in the 1980s, but Gossard had seen McCready play a blazing cover of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Couldn’t Stand the Weather” in his little Seattle band Love Chile, and Gossard loved it.

This night, the guitarists ducked back into the Oxford Tavern and talked music for a while. McCready suggested Gossard should start playing with Love Bone bassist Jeff Ament again. McCready told him, “We’ve got to get Jeff, because you guys together are really great.”

“I was going through a major identity crisis at that point,” said Ament. “I’d put my heart and soul into Mother Love Bone, gave up school, and to have it be snuffed out so quickly. All summer, Stone and I would meet up, mountain bike and just talk. We aired our grievances with one another. He told me that I needed to lighten up a bit and I told him that he needed to take it more seriously.”

Soon, Gossard, Ament, and McCready were jamming in Gossard’s parents’ attic in Capitol Hill, where his other bands Green River and Mother Love Bone had jammed, too. Together they refined some of their riffs and sketches into instrumental songs. Some were new, like the music McCready wrote that became “Yellow Ledbetter” and Ament’s music that became “Jeremy.” Others Gossard had carried over from Love Bone, including one jam named “Dollar Short.” Andrew Wood had even written full lyrics for “Dollar Short” before he died. “I think we played it at the last Mother Love Bone show at Satyricon,” Gossard told one interviewer. “There’s a taper down in Portland who might have it. I’ve never heard it [again], but I’m super curious.”

Eventually, the three added the best drummer in Seattle, Soundgarden’s Matt Cameron, to make a 12-song demo at Chris Hanzsek’s Reciprocal Studio in Seattle. Hanzsek had made Seattle’s first modern rock compilation Deep Six there in 1986, which predated the influential albums Nirvana, Mudhoney, and Soundgarden would soon record at Reciprocal with engineer Jack Endino. Mother Love Bone recorded their first demos at Reciprocal in 1988. Hanzsek labeled Gossard and Ament’s new session tapes “Stone and Co.” The guys reduced the material to a five-song cassette composed of “Dollar Short,” “Richard’s E,” “E Ballad,” “Footsteps,” and “Agytian Crave.” The tape contained no vocals. To find a new singer and permanent drummer, the musicians passed their instrumental tape around to friends and industry contacts. They gave a copy to Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell. Gossard mailed a copy to Michael Goldstone, the A&R guy who signed Mother Love Bone to PolyGram Records and recently transferred to Epic Records. The band sent a copy to drummer Jack Irons, who’d co-founded the Red Hot Chili Peppers, to try to entice him to be their drummer. He couldn’t do it, but he gave the tape to a San Diego surfer he played basketball with, named Eddie Vedder.

Vedder was working overnight shifts as a security guard at a Chevron petroleum warehouse in San Diego. His local band Bad Radio had just folded. But he was ambitious and searching for opportunities.

On September 13, 1990, Vedder listened to the tape during his overnight shift. He played it over and over. After work the next morning, he went surfing at Pacific Beach and composed lyrics to three of Gossard’s instrumentals. The melodies, the words—they came to him nearly complete.

“When you haven’t slept for days, you get so sensitive that it feels like every nerve is directly exposed,” Vedder later said. "I went surfing in that sleep-deprived state and totally started dealing with a few things that I hadn’t dealt with. I was really getting focused on this one thing, and I had this music in my mind at the same time. I was literally writing some of these words as I was going up against a wave.”

Still wet from the ocean, he raced his black ’89 Toyota pick-up to his girlfriend’s place in Mission Beach to record his vocals before he forgot them. All he had was Merle Haggard’s Best of The 80s cassette compilation, so he used his four-track to mix the music and vocals together on that. During his next overnight shift, he used White Out and his office copy machine to make cover art for the cassette. The next day, Friday, September 14th, he sent the guys back the tape, scribbling “For Stone + Jeff” across the top. The tape contained “Alive,” “Once,” and “Footsteps,” two of which became some of their most famous songs.

Ament listened to the tape first. He played it three times then called Gossard. “Stone,” he said, “you better get over here.”

Vedder’s vocal versions blew the Seattle musicians away. Mike McCready listened and asked: “This is a real guy?”

Contrary to Pearl Jam lore, Vedder didn’t first meet the band in Seattle after separately writing these songs. Ament and Gossard actually arranged to meet Vedder in Los Angeles before flying him north. To promote Love Bone’s album Apple, they did a press event at the Concrete Foundations Forum metal convention, at a hotel near LAX, in mid-September. Irons facilitated. “We met him at the Hyatt hotel and said hello and just got to look at each other,” Gossard told one interviewer. “Immediately, he was a humble guy and really excited. He played it pretty cool and it seemed right.”

“Stone and Jeff saw talent in Eddie that no one else did,” Rocket editor Charles R. Cross said. “One part of the story that never, ever gets told, is they could have picked 20 other lead singers. There were other people in Seattle that certainly would have approached them.”

On September 19th, they invited him to Seattle. By the time Vedder arrived on October 8th, he’d written lyrics to the song “Black” over Gossard’s “E Ballad” instrumental. They spent their first week jamming in the band’s Belltown basement rehearsal space. They called it Galleria Potatohead. It stood in an alley between Second and Third avenues, underneath the Black Dog Forge ironworks. The Forge’s owners, Mary Gioia and Louie Raffloer, didn’t pay the band much attention. Musicians all over downtown practiced in tiny basement rooms, and these ones were polite and benign.

“It’s not like we had Steven Tyler downstairs,” Gioia told The Seattle Times.

“They were working on a record that was going to make them world-famous, and we didn’t even know it,” said Raffloer.

During that first week together, the guys wrote 11 new songs. The instrumental “The King” became “Even Flow.” “Richard’s ‘E’” became “Alone.” “Evil ‘E’ became “Just a Girl.”

“I’d never been in a situation where it clicks. It all happened in seven days,” McCready said. “It was very punk rock. Eddie would stay there in the rehearsal studio, writing all night. We’d show up and there was another one. And then he had to get back [to San Diego]. I remember giving him a ride back, at about five in the morning, to Sea-Tac Airport. I remember him saying ‘Don’t be late!’ He had to get back to work.”

“The minute we started rehearsing,” Ament said, “and Ed started singing—which was within an hour of him landing in Seattle—was the first time I was like, ‘Wow, this is a band that I’d play at home on my stereo.’ What he was writing about was the space Stone and I were in. We’d just lost one of our friends to a dark and evil addiction, and he was putting that feeling to words. I saw him as a brother. That’s what pulled me back in [to making music]. It’s like when you read a book and there’s something describing something you’ve felt all your life.”

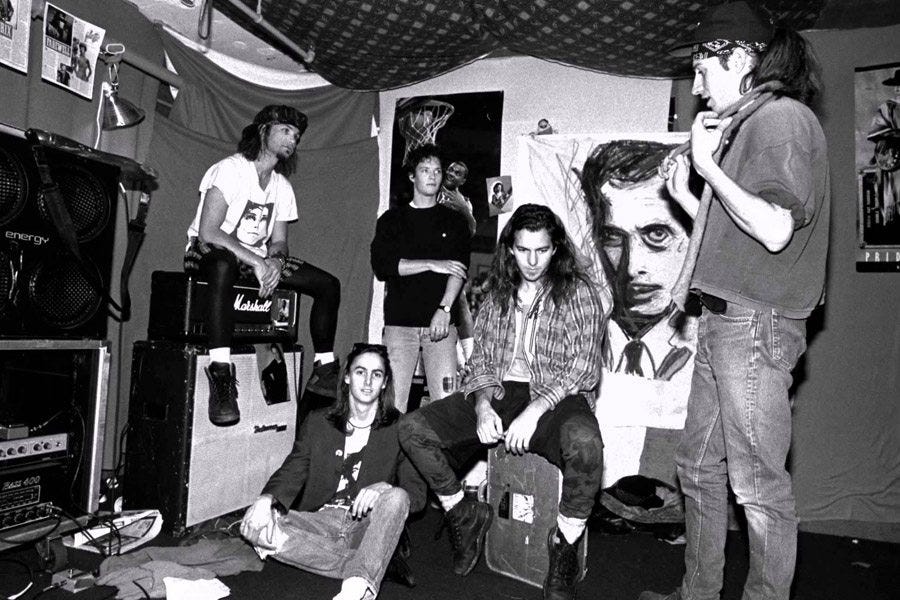

On October 22nd, the band played their new songs to an audience for the first time. The show was at the Off Ramp Cafe. They didn’t advertise it. About 200 people showed up. Thankfully one filmed it. This was what Gossard and Ament had hoped for: a musical life after Love Bone, a way to keep playing through their grief. Wood had only died eight months earlier.

“They just said, ‘We’re going to go down to this club and play,’” their first drummer Dave Krusen said. “We were still learning the songs. It was nerve-wracking. They just wanted to set up and play, get on stage and see how it felt.”

“By the time we were done, it had filled up a little,” Krusen said of their debut. “I thought it was great—the energy was there, and I was really blown away with Eddie.”

They’d named their band Mookie Blaylock, after a basketball player, but renamed themselves Pearl Jam to avoid a lawsuit. Because their previous A&R guy had their tape, they already had major label interest, and he eventually signed them to Epic Records, where the songs they’d written that fall became their international success, Ten.

Whether you think of this band as a ’90s artifacts or you loath the over-played singles from Ten, you have to admit that’s an incredible origin story. Something powerful sparked between these musicians. As creative events go, that is one in a million.

At the time this was happening, Chris Cornell was writing his own music about his fallen friend Wood.

“That was the only thing I could really think of to do,” Cornell said. “The songs I wrote weren’t really stylistically like something my band Soundgarden would be used to playing or be natural for us to do, but it was material that Andy really would have liked, so I didn’t really want to just throw it out the window or put it away in a box, y’know, put the tape away and never listen to it again.” Cornell had watched Gossard turn his mourning into art, so he kept writing, too, and he shared his demos with friends.

“I had written ‘Say Hello to Heaven’ and ‘Reach Down,’” Cornell told Spin, “and I had recorded them by myself at home. My initial thought was I could record them with the ex-members of Mother Love Bone as a tribute single to Andy. And I got a phone call from Jeff, saying he just thought the songs were amazing and let’s make a whole record.”

Soon Cornell turned two of Gossard’s instrumentals into the songs “Times of Trouble” and “Pushin’ Forward Back.” Before the month-old Pearl Jam had recorded anything in a studio, Cornell pulled the band’s two guitarists, their bassist, and his own Soundgarden drummer Matt Cameron, into what in hindsight resembles a super-group. They called their one-off project Temple of the Dog, using Wood’s lyric from Love Bone’s song “Man of Golden Words.” In less than three weeks in November and December, 1990, the band recorded their only album.

“Yeah, the whole situation was just so non-pressure filled,” Gossard told KISW radio in 1991, “nobody expected this to be anything, so when we just went in and did it the record company wasn’t around, we basically paid for it ourselves to start out with and are still in the process of getting reimbursed for that.”

It was just friends playing with friends.

“I first met Eddie in a waiting room [outside our common rehearsal space] the day he first got to Seattle,” Cornell remembered. “He was very quiet and very shy and didn’t have a lot to say. He was under a lot of pressure, a lonely guy away from home in a room full of people who had a lot of experience in bands.”

People described Vedder as painfully shy. Walking into this situation in Seattle would have challenged the most extroverted personalities. Because people were still mourning Wood, some folks were skeptical about this new arrival playing with Gossard and Ament. As club owner and Soundgarden manager Susan Silver put it: “[T]he feeling I was picking up from the audience was ‘Who is this guy? Is he good enough to fill Andy’s shoes?’” Surely Vedder felt that. His newness also helped fuel this album’s magic.

“When we started rehearsing the songs,” Cornell remembered, “I had pulled out ‘Hunger Strike’ and I had this feeling it was just kind of gonna be filler, it didn’t feel like a real song. Eddie was sitting there kind of waiting for a [Mookie Blaylock] rehearsal and I was singing parts, and he kind of humbly—but with some balls—walked up to the mic and started singing the low parts for me because he saw it was kind of hard.” By singing those low parts, Vedder freed Cornell to sing the high parts. The result sounded exactly how Cornell had envisioned it, and he’d never described anything. “History wrote itself after that,” said Cornell, “that became the single.”

“That was the first time I heard myself on a real record,” Vedder later said of their “Hunger Strike” duet. “It could be one of my favorite songs that I’ve ever been on—or the most meaningful.” “Hunger Strike” became the band’s big calling card. For Vedder, that duet was a hell of a whirlwind welcome to Seattle.

Temple was also the first full-length album that Mike McCready ever recorded. “That was my first lead on an album, and I was so excited,” McCready remembered. “I’d been in a studio before, but never to record an album or anything.”

When it was time to record “Reach Down,” McCready got the entire five-and-a-half minute section in the middle to solo on, but he was so diplomatic, so green, that he was concerned about overstepping. Cornell had to tell him: This is your slot. Do whatever you want with it. As McCready’s idols Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan had before him, McCready took the opportunity to wail. “I did that in one take! I soloed through the whole thing and ended up with the headphones wrapped around my face.” With the headphones off his ears, he couldn’t hear the music, so he played most of that solo without hearing the backing track. “The guitar work in that track represents one of my proudest moments.”

Temple of the Dog came out in April 1991. It only sold 70,000 copies of its initial print run. Although the album was eclipsed by Soundgarden and Pearl Jam’s own albums, those bands’ mega-visibility eventually brought attention back to this incredible album that they’d slipped in before everyone was looking. And many listeners, myself included, hold it up as one of the best albums of the ’90s.

“I still listen to it and think that it’s the best thing I’ve ever been involved with,” Gossard told Spin. “Whatever that combination of people was, I’d never been in a situation where it was that easy. I’ve almost been looking for that ever since. The very first thing we did was a very high water mark, the way that our two bands complemented each other. And it was a bunch of songs that Chris wrote totally from the heart. He wrote these songs without any preconceived notions of where they might end up or what they were going to be. That’s where the real gold is. In terms of writing music, being self-conscious is the worst place to be.”

In 1991, “Hunger Strike” played regularly on MTV, even before Pearl Jam did, which confused me: Why were these two Seattle bands all in this song? What was this band? I was young. What had initially confused me eventually made sense as a side-project, and the one-off albums’s best songs like “Pushin’ Forward Back,” “Reach Down,” and “Times of Trouble” are as good as the member bands’ best songs. But by the time it came out, the musicians had all charged off into their main musical projects and raced into their futures, which is how we found them at the 1991 show: fresh and new, excited about what they were creating.

Pearl Jam approached their first tours the way they approached their first show: as a chance to have fun. “We told the record company, ‘We know we can be a great band, so let’s just get the opportunity to get out and play,’” Ament remembered. They did a string of dates along the West Coast opening for Alice in Chains. They played clubs back East and out West. They eventually toured for Ten to the point of exhaustion.

“People didn’t know what it was,” Pearl Jam manager Kelly Curtis said about Ten. “Once people came and saw them live, this lightbulb would go on. Doing their first tour, you kind of knew it was happening and there was no stopping it.”

“The first thing I remember of Pearl Jam was hearing ‘Alive’ on the radio while I was living in Seattle,” said Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl. “I pictured Mountain or some serious ’70s throwback. The music just seemed like classic rock to me, so I pictured the singer being some husky, fuckin’ bearded, leather-jacketed Tad type, big and fat and tortured and scary.” No. It was a shy surfer.

Behind the scenes, people helped lift them from tiny clubs to huge stadiums. Drummer Jack Irons—the same friend who gave their demo tape to Vedder—had urged his Chili Pepper friends to add Eddie’s new band as openers on their big fall Blood Sugar Sex Magik tour. Irons insisted: PJ was good.

In 1991, the Chili Peppers’ music was all over MTV. This follow up to their 1989 album Mother’s Milk would deliver them to the mainstream audiences where they’d remain. And these would be the biggest venues Pearl Jam had played, and a way to quickly build their audience. The Chilis accepted Irons’ suggestion, but tour promoters, concerned with ticket sales, insisted on adding The Smashing Pumpkins and Nirvana to the lineup, going so far as to suggest they replace the unknown Pearl Jam with an established band. Pearl Jam took the chance. They canceled the rest of their first North American tour halfway through to take the opening slot. The Smashing Pumpkins only played a few shows on this tour, and thankfully, both Pearl Jam and Nirvana stayed on. That made the Chili Peppers the oldest musicians on the tour, the glue that held the rest of this uneasy musical union together. In hindsight, Spin called this tour too short but “the Holy Grail of early ’90s alt shows.”

That means that, barely over a year after Vedder first listened to Stone and Co’s demo during his night shift, the band was playing this huge arena in front of teens like us. Magic happens fast.

Once I’d gotten deep into listening to live recordings of Jane’s Addiction and Depeche Mode, I wanted to record something myself. I imagined my friends and me creating bootleg tapes with nice artwork and packaging like the ones in our collections. I envisioned fans listening to our recordings in their bedrooms and how the experience would permanently change them, the way live music had changed me. We’d make our own fake label modeled after the famous bootlegging company the Smokin’ Pig (I later chose the name Hissing Gila) and release other concerts too. Somehow we’d send them around the country. Maybe Tracks in Wax, the record store next to my high school, would even sell copies.

As a music obsessed teen, I loved the singular power of live music. I loved the things musicians said on stage between songs, the way fans rushed the stage and the band egged us on. And I liked how live recordings were a document of particular moments in bands’ lives that combined into a historic record of art in America in different eras. For me, this went beyond music fandom. Because my sentimental streak intersected with my documentarian impulse, I’d long tried to capture bits of daily life. As a kid I recorded the radio on my stereo, the sounds of birds in a park, even ambient noise on the sidewalk. These were sonic photographs. It was time to do that to rock ‘n’ roll.

My parents had given me a Panasonic handheld cassette recorder and a microcassette recorder to play with. The micro was what people used for dictation in their offices. Its tapes were too small to play on anything but those proprietary machines. I don’t know what I planned to do with it: transfer it to a larger cassette? I tested them out, standing it in different locations in my bedroom to see how clearly it captured loud music from my record player—not well, but it seemed good enough. The main challenge was access: How did people smuggle recording equipment into shows? The Panasonic was the size of a brick. Security had been tight at the big Depeche Mode, Lollapalooza, and KUKQ music festival shows that year. Guards searched our shoes for drugs and patted between our legs. I couldn’t Google “how to record a rock show” back then. If certain zines discussed techniques for smuggling in recording equipment, I wasn’t cool enough to find them, so my friends and I brainstormed.

Someone suggested I tuck the equipment under my balls, since guards might not check there.

My balls were too small.

Someone suggested I slip the recorders inside of some tall boots. After all, that’s where the name “bootleg” came from, so it had to work, right?

I wore Vans, though. I didn’t own boots.

Someone said: What about a hat with a thick band or flower arrangement that could conceal the equipment, like Perry Farrell’s weird stovetop hat in the Soul Kiss video?

But bold fashion would only attract scrutiny.

If someone had a wheelchair, we could roll the equipment right in. Or crutches. Can’t someone break their leg for the cause?

I got nervous. What if security caught me? Did I get arrested or just barred from entrance? Not getting to see the show would be worse than incarceration.

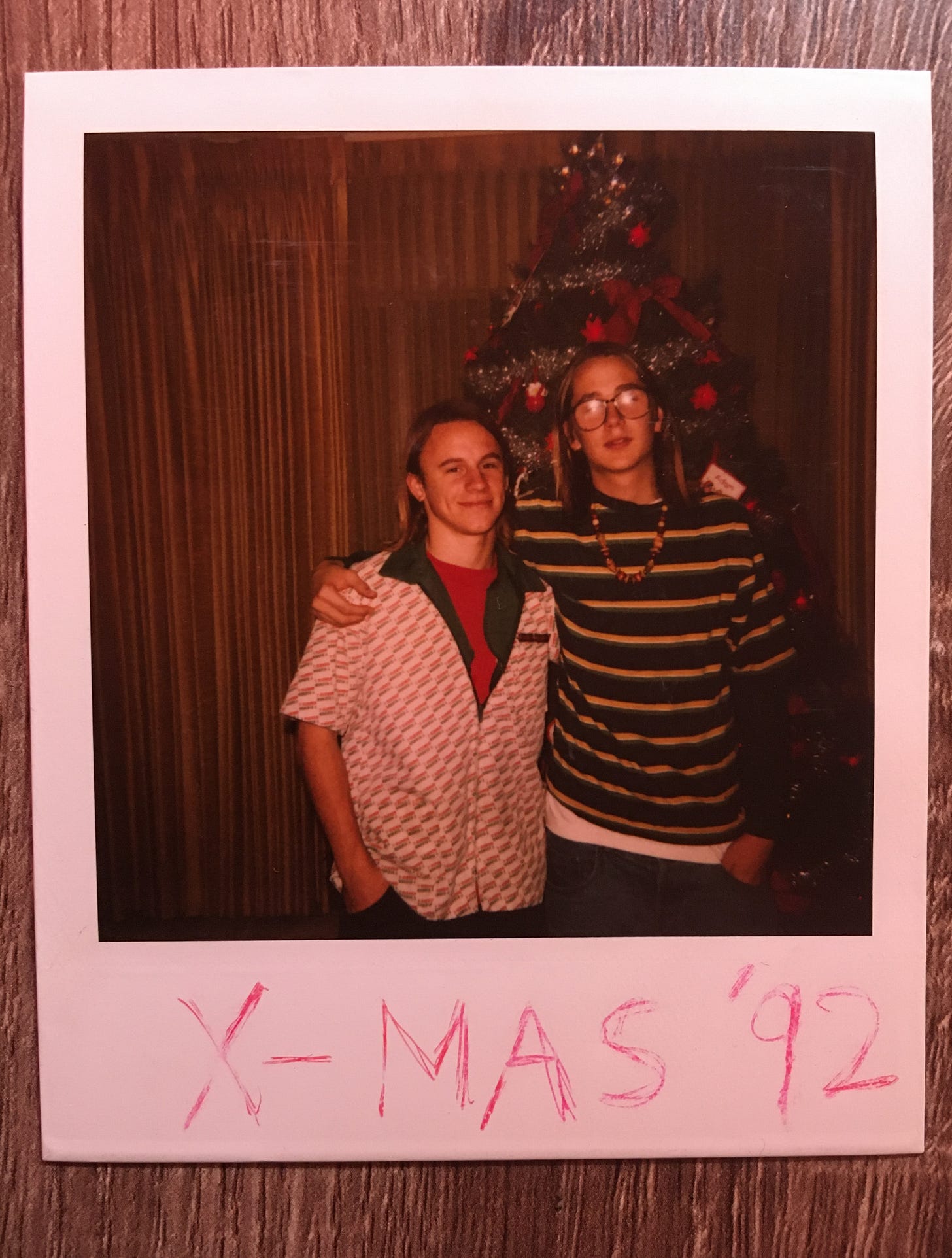

Our friend Liz had a suggestion: “Maybe I could put them between my boobs?” She sheepishly shrugged and raised her thick brows. Cleavage—that made sense. Liz was another close friend whose cool tastes influenced me. In 1991, she wore a Meat Puppets shirt with one of the band’s signature, acid-induced monster drawings on it. I only knew the band from the flyers. She actually listened to them. She knew tons of other bands. She played vibes in her high school band, eventually became a professional musician and teacher, and turned me on to lots of music, as friends do. Tonight, she offered her body for the cause, and we hoped that no security guard would violate her privacy while checking for contraband. I didn’t want to get her in trouble, but she insisted: I’ve got this. We decided to split it: She’d take the big recorder. I’d take the microcassette.

I listened to Nirvana and Pearl Jam constantly during the weeks before the show, and I worried as we drove to the venue. What if they don’t let us in? What if some scumbag feels up Liz?

A huge line of kids had formed outside the coliseum. They were dressed to impress, with eye liner and dark gothic lace dresses over black leggings, black boots, and many, like us, wearing flannels, Doc Martin’s, and baggy jeans. No one in our crew did that cliché Grunge thing where they wore thermal underwear and shorts with Docs. I didn’t do the super-90s clown-sized baggy clothes thing, either. As Phife Dawg from Tribe Called Quest said: “Word to God, hon. I don’t get down like that.” I mean, my big pants definitely sagged. It’s embarrassing to admit, but I’m proud to say I favored thrift store button-ups with huge collars, Stussy tees, and cut-off jean shorts. That said, I committed my own fashion crimes: black socks with Birkenstocks. In line at the show, though, nerves made me wish we had gone for the baggy clown clothes look. It would’ve provided more room to conceal the machines.

Liz and I exchanged looks. “Okay,” we said, “here it goes.”

As we stood in line, I turned toward the wall and shoved the micro recorder into my pants, tucking it under my balls in a way that the ball moisture seemed to hold it in place. The boys circled Liz as she wedged the big recorder into her ample cleavage. The security guard lightly patted me down and never touched my crotch. No one touched Liz’s chest. I don’t remember where my extra blank microcassettes went, maybe inside Jason’s Doc Martin boots, but somehow we got them in. It was so easy that I regretted not buying a fancy external microphone, but I didn’t know they existed.

Safely inside, we pulled out the equipment and found our seats high on the back side of the venue, in section P, row 18. This area was distant but at least afforded an unobstructed view of the stage, directly over the crowded floor. As we sat, general admission people filled the area right in front of the stage. I envied the floor people. They’d see all the details we missed: the musician’s expressions, the glistening sweat. They’d get to jump together in the pit while we sat up here like elderly chaperones. Another part of me knew how hard it was for us short kids to see over peoples’ heads, and, I told myself, back here, far from the speakers, I could get a clear-sounding recording.

I tested the gear, searching for the best way to hold both recorders so the microphones aimed at the stage without hovering so close to neighboring fans that the mics heard their screams. I had to keep the equipment close to my chest, too, so security wouldn’t see. In the dark arena, the red ‘record’ lights would give me away. Since we’d made it this far in the bootlegging process, it would sting worse to get the tape snatched halfway through the show. That would happen to me ten years later, and it sucked.

When the house lights went dark, the stage lit up, and the crowd erupted in applause. After a few charged seconds, a long-haired guy in cut-off army shorts skateboarded onto the stage, rolled right into a monitor, and flung himself onto his side. It was Eddie Vedder. The band strutted out behind him and picked up their instruments. When Vedder popped back onto his feet, he flung his hair from his face like you would fling a curtain, and he waved to the crowd. I hit record. The red lights glowed, and my eyes locked on the stage. It was so far that the band looked like tiny action figures in a mobile.

They started with “Wash,” a slow moody song that didn’t make Ten but that directed everyone’s attention at them. Then they tore into “Once.” From the first notes, the band made it clear why Jack Irons lobbied so hard for them. They ripped through “Even Flow,” “Alive,” “Jeremy,” “Why Go,” all of which I recognized thanks to Jessica.

They leapt off the drum riser. The guitarists ran back and forth across the stage past each other, launching into the air, sometimes leaving four of the five members suspended mid-air at once. Vedder flung his body around, his flannel shirt tangling around his arms, sometimes taking his whole body down. He flung around so hard that it looked like his shirt was attacking him. He seemed to like the abandon. At one point he dropped the mic and dove into the audience, where the spotlight zigzagged back and forth trying to find him. When it did, it locked on the cinematic image of his body floating atop peoples’ hands. I’d never seen stage-diving like this. It was one of the images that would define the ’90s.

The way the band jumped around, they played like they had something to prove, because they did. They were the opening band. Their album hadn’t hit big yet. They were singing to many kids who wouldn’t know their songs until the following year. Some were still the songs Eddie had written on the beach.

Between songs, Pearl Jam played a few bars of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and told the crowd, “Remember, we played it first!” That hit song had just come out in September.

This might have been something I heard on another show recording, but I have a vague memory of Vedder taking the time to speak up for women between songs, too, and informing all the boys in the audience about what the men in their lives may never have said: “Hey, there’s a thing called date rate. Don’t go partying on someone’s pussy unless they invite you.” Veddar was referencing the Chili Peppers’ misogynistic song “Party on Your Pussy” and all the offensive sex-rap crap like it. Whether that was at our show or another, I’ve always loved Vedder for that.

The highlight was when Vedder climbed all the way up a hanging rope ladder during the instrumental bridge in “Porch” and hung upside, over the crowd. He strained as he climbed. In the spotlight you could see how much effort it took, with the thin rope ladder swinging back and forth as he went. It seemed too dangerous to be real. If he fell, he would die, and the band would have to break up. That would make to deceased lead singers. Every so often I glanced at the red lights to make sure my tapes were rolling. Vedder hung upside from the ladder, above everyone’s awe-struck heads, and sang the last lines of “Porch” from the top of the venue. If only I had a video camera, I thought.

Apparently, climbing had become his thing. “Early on, we always made bets on where Eddie would climb to jump from,” KISW music director Cathy Faulkner remembered.

Vedder kept outdoing himself. The escalation got scary.

The day before our show — on December 28, in San Diego — Vedder realized he’d gone too far.

“I had climbed an I-beam that you could kind of wrap your hand around,” Vedder remembered. So he climbed up this vertical beam until he reached a thick metal crossbeam that ran along the venue’s ceiling. That one was moist and dusty, but he managed to get a grip and inch along it upside down, above the crowd, parallel to the ground. “And all I remembered was that I had people that were in my family that were there, and I already committed, and I was upside down doin’ this thing, and I thought, This could go wrong.” At the top he also wondered, Well, how do I get down? “I either just give it up and look like an idiot,” he said, “or I go for it. So I decided to try it, and it was really ridiculously high, like 100 feet, something mortal. I was thinking that my mother was there, and I didn’t want her to see me die.”

“There’s that whole aspect of him,” McCready said of that show. “He used to make me crazy.”

The band kept playing the instrumental bridge, often while staring straight up, wondering how this would end.

“I knew that was really stupid,” Vedder said, “beyond ridiculous. But to be honest, we were playing before Nirvana. You had to do something. Our first record was good, but their first record was better.”

“I didn’t sit and watch them play until the show in San Diego, where Eddie climbed the fuckin’ lighting rig,” said drummer Dave Grohl. “It was one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen live in my entire life. I’ve seen people cut themselves, I’ve seen people shit, I’ve seen people get beat up onstage, and I’ve seen people break bones, break their backs, and get concussions. Honestly, I was horrified.”

My friend Peter watched from the audience, rapt.

“I mean, I had this thing,” Vedder said smirking, “if you cut your arm off and waved it around and slattered blood all over the front rows or whatever, that would be a legendary performance. And then if you were known for that, well you’d only have three more good gigs in you. You’re going to have to taper it down at some point.” He managed to get down. He finished singing “Porch,” then he vomited off-stage. “Because I knew that was the one. That was the one I was—” He held up his fingers to show the margin of error. “Centimeters—This was my life. I was on the edge.”

And yet, the very next night at our show, he sang “Porch” while hanging upside down over our crowd, too.

My friends and I stared in awe.

When Vedder descended back onto our stage, the band waved and left. A collective sign left the stadium. A stadium full of people had been holding our breath. We traded amazed glances. That was one of the most energetic shows we’d ever seen. I couldn’t believe I’d captured it on tape! I had big plans for these tapes. When Nirvana came on, I did the exact same thing: held a recorder in each hand and watched both the show and the red lights.

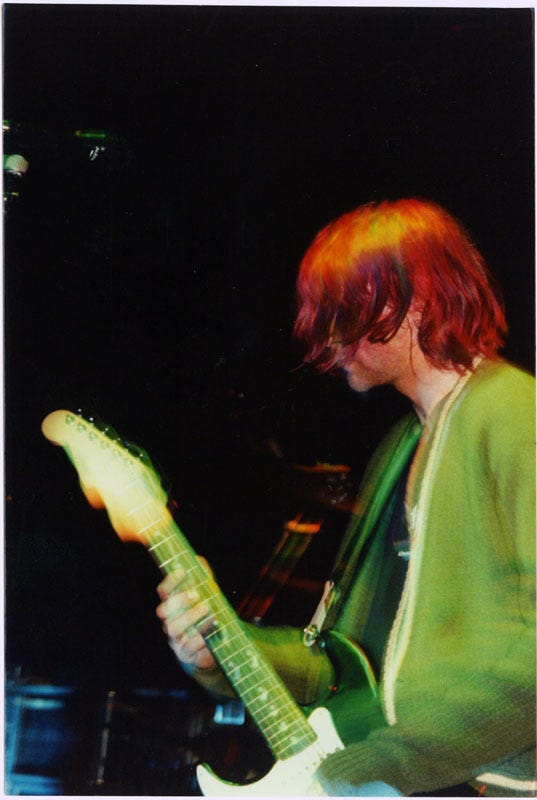

The stadium went dark. Nirvana walked on stage. Kurt Cobain leaned into the mic and said, “Good morning,” then they tore into “Drain You.” For a mesmerizing hour, they played songs like “Aneurysm,” “Floyd the Barber,” “Silver,” “School,” and “About a Girl,” some of my favorites. I didn’t realize that I would never hear these songs live again. At that age, without the benefit of experience, you just figure a band this good will be around forever.

Grohl had joined the band a year earlier, and he was all swinging hair and sticks. In the summer of 1990, Grohl’s band Scream had suddenly broken up on tour. When he sought advice from Melvins’ singer Buzz Osborne, Osborne gave him Cobain and Novoselic’s phone numbers. Nirvana was looking to replace their last drummer Chad Channing. They invited Grohl to audition in Seattle. “We knew in two minutes that he was the right drummer,” Novoselic said. They played their first show together at Olympia, Washington’s North Shore Surf Club on October 11th, two days after Vedder arrived in Seattle to audition for Pearl Jam. When the owner booked Nirvana, he thought they were just a local band, until he saw the line of fans snaking around the block. Of course, the Live Nirvana Archive crew unearthed multiple video sources of Grohl’s first Nirvana show.

Dave was the right choice.

Even from our distance in Phoenix, you could see how hard Grohl played his drums, putting so much force into every hit. Novoselic jumped up and down in his lithe, top-heavy way, awkwardly lunging and keeping time with his thrusting body. Nevermind had sold 3 million during the last four months. The band had just returned from touring the UK. They were about to become the biggest band in the world. Yet Cobain barely moved. He sounded great. He flailed around during “Aneurysm.” He swung his guitar back and forth as he strummed. I think he wore a white lab tech coat, but the leader of the band that Option magazine said “throw [their energy] off in enormous bursts” was pretty sedate. He stood in one place, occasionally pushing his hair from his face and adjusting his effects pedals. Novoselic and Grohl did the moving for him. Then during the solo in “School,” he suddenly ran toward Novoselic, leapt into the air, and landed on his knees, sliding across the stage with the neck of his guitar straight in the air. Even as a skater used to landing on my knees, that looked painful. The crowd went nuts. The crowd went nuts again when Vedder ran onstage during “Breed” and dove into the crowd. Vedder couldn’t seem to get enough.

“Aneurysm” was and remains one of my favorite rock songs. Hearing the band play it live, at that volume, remains one of the highlights of my musical life. And it only lasted four and a half minutes.

Nirvana finished with “Come As You Are,” “Lithium,” and “Territorial Pissings.” Then Cobain whispered “Thank you” and left.

Again my friends and I looked at each other, stunned. Between Nirvana’s set and Vedder hanging dangerously, it was clear that we’d witnessed magic.

Before the Chili Peppers came on, I slunk down in my seat and held the recorder to my ear. I had to hear some of this performance again. I listened to the playback. It just sounded like crowd noise: hissing, static, loud booms overlaid with fuzz. Uh oh, I thought. Adrenalin filled my chest. Maybe it’s the tiny Panasonic speakers, I told myself. Maybe I need big home stereo speakers to handle the volume. I put aside my worries to tape the Chili Peppers, but with much less attention or interest. The shirtless band strutted and flailed away down there, singing their new caveman songs about “suck my kiss” and “put it in you” and all that. After they left the stage, I leaned close to my speaker and listened again.

“It doesn’t sound good,” I told everyone.

It might just be the speakers, someone said.

Out in the parking lot, we played the tapes in our car’s cassette deck. It wasn’t my speakers. Loud rock ‘n’ roll had overwhelmed my equipment’s primitive microphones. The tapes were unlistenable. I had fucked up my one chance to preserve this! Why had I believed these toys could accommodate the strength of amplified guitars?

The disappointment lingered for days.

Despite this, we stuck to our plan to sell copies at school. JR worked at an Alphagraphics copy shop. To make a cover, I cut up the concert flyer, combined it with a band photo against a lipstick red background, and JR shrunk it down so we could fold it into the cassette case. We made duplicate tapes on our home stereo system and handwrote the setlist on the master. Nirvana’s “Polly” was the only song in all three sets that sounded good. Since it was mostly Cobain strumming guitar, there were no drums or low-end to distort anything. That one song made me proud. Instead of seeing our debut concert recording sold in stores like Track in Wax, this piece of shit recordingbecame a memento of our momentous event, a sonic photo of our fun night, and it was proof that we’d evaded security and captured one of the world’s most famous bands, if only as a trophy. Even though I sucked at it, I was now officially a bootlegger, a member of an elite, elusive club of black market documentarians who made the illicit masterpieces I kept buying at Tracks in Wax. At least our cover looked great.

One thing Depeche Mode bootlegs had taught me freshman year was that cover art mattered. The worse the fidelity, the better the packaging had to be. Anyway, bootlegs were a niche market. They were for collectors and extremists, not the average fan, which is why barely anyone at school wanted to buy our tape.

I’d always doubted the Van Halen fans at my private school would even know what Nirvana or the Chili Peppers were. I didn’t talk to them enough to find out.

I sold one copy, to my buddy Bo. He liked DM and alternative music. He came back the next day to complain.

“It sounds like shit,” he said. “It’s unlistenable.”

I shrugged. “It’s a bootleg.”

He stared at me for a few seconds too long. “Okay,” he said. “Whatever. Rip-off.”

It worked out. Bo and I played in a short-lived band together. But I never refunded his money. Maybe I turned him onto Pearl Jam the way Jessica had turned me on? That’s how this all worked back then. “The band did such an amazing job opening the Chili Peppers tour that it opened doors at radio,” said A&R man Michael Goldstone. “You look at how long that record took to explode, and it was exactly how they would have wanted it—not having it shoved down everyone’s throats the first five minutes. People got to discover Pearl Jam on their own: The kid on the street took all of his friends, and then the next time through everyone came.”

Twenty-five years later, JR took to Facebook to post live footage of Pearl Jam playing in Daly City, California two days after the show we saw in Phoenix. JR was celebrating our show’s 25th anniversary. Celebrating was better than mourning how much time in our lives had passed. I tweeted about taping it. David, the busy German student who volunteered for the Live Nirvana web archive project, contacted me for a copy. Now here we are, still talking about. It didn’t matter that my recording sucked. Countless soundboard live Pearl Jam and Nirvana recordings have surfaced over the year, most more inspired shows than ours, like Nirvana’s 1991 show at Chicago’s Cabaret Metro. My bootlegging errors were no great musical loss.

So yeah. We saw Nirvana. From way too far away, but goddamn, was it good. Students I’ve had at various teaching jobs have marveled: “Whoa, you saw Nirvana?” Hey, it trips me out too. It’s a twist of perception. Every generation looks back at the glow of the previous one’s summer sun, marveling at the parts of the grass that seemed greener. I love Jimi Hendrix. I’ve meet people who saw Hendrix play. I wish I could have seen Hendrix, until I think how much closer to death I’d be now if I had. Instead, I’m the legacy band’s target demographic, one of the middle-aged throngs screaming too loudly on the bootleg, the head bobbing in the way of the camera footage. My friend Peter sent me a YouTube link of Nirvana playing an in-store in San Diego: That’s me at the six-second mark, he said. He’s a few rows back from the front, still magically close to Cobain. Shows leave a mark on you. “Negative Creep” and “Dive” are incredible songs at any age. But many YouTube videos of Nirvana playing “School” are more dynamic than the show I saw. In a sense, watching something that powerful from that far away was like watching it on TV while it was happening. That’s why arena shows can suck. The physical distance cools the heat and reduces the band to characters on a screen, almost like images in someone else’s eyes. That’s partly why I still wish I had a single photo from this show, just one clear image of the way the stage looked from our nose bleed seats, to confirm the way it appears in my increasingly hazy memory.

Even more, I wish I could ask share the joy of remembering with JR, but he died two years ago, at age forty-three.

Middle age is the center of a circle. The circle of life is incomplete.

Naturally, the first Nirvana song my wife and I played for our daughter had to be “Aneurysm.” She’s three and a half. She danced and banged her head in the living room so hard that she had to hold onto a bookshelf to brace herself.

“Girl,” I said, “I know the feeling.” We were all dancing around the living room, playing air guitar. If JR was alive, he would have loved to see me headbanging my bald head with her. Maybe Cobain would’ve too. He’d be 54. Vedder’s 57.

Sometimes I envy that magic of accidental collaboration that courses through the music. We don’t have that in the writing world, I think. Loved learning that backstory to Pearl Jam.