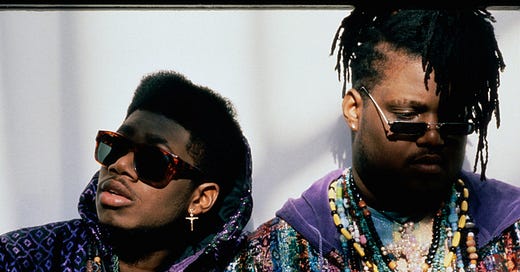

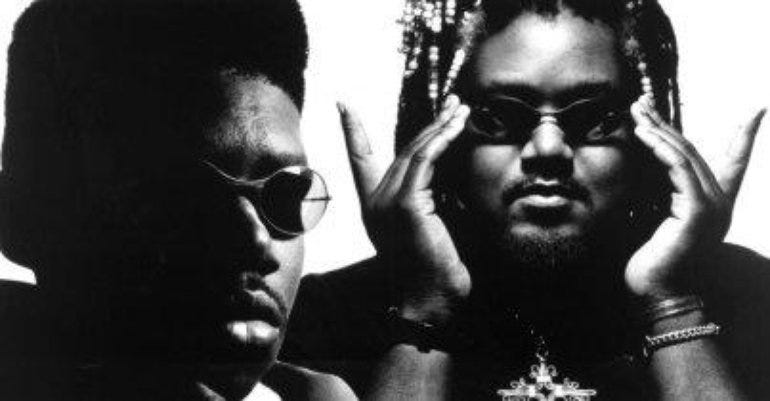

“If P.M. Dawn came out today they would be Gods,” someone once posted on Twitter, and, as a fan of the group’s avant-garde hip-hop soul sound since the beginning of their careers, I agree. Unlike the closed minds of decades past that had a problem with the cosmic freakiness that Prince Be (Attrell Cordes) and his younger brother DJ Minutemix (Jarrett Cordes) introduced in 1991, new-millennium fans are more open towards experimentation. In addition, artists such as Kanye West and Childish Gambino, who once covered the duo’s wondrous soul track “I’d Die Without You,” have celebrated the P.M. Dawn’s innovation and taken it as inspiration.

These days we can hear and see P.M. Dawn’s influence in artists such as Solange, Frank Ocean, and other kooky creatives who have no problem waving their freak flags in stereo. Certainly, as Record Redux book series author and Albumism columnist Quentin Harrison says, “P.M. Dawn’s sound and visual aesthetics always felt like the something from another time and that ‘against the grain’ motif they wielded fearlessly has been taken up en masse by others. At the same time (in the 1990s) acts like Maxwell, Erykah Badu, and D’Angelo (among others) were reaping the benefits of the path P.M. Dawn helped pave for neo-soul.”

Back in the day, things weren’t always so diverse. As someone who lived through the gritty boom-bap era of the 1990s’ realness, when roughness equaled righteousness, rap music could be a brutal, sometimes deadly, profession, and the slightest dis could lead to the coldest response either on record or in person. In P.M. Dawn’s case, their 1992 clash with self-proclaimed teacher KRS-One was unexpected. “I never knew there was a beef until that night,” Prince Be told me when I interviewed him for Vibe magazine in 1995. Be was flopped down onto a comfortable white leather sofa in the living room of his Jersey City penthouse. A signed lithograph self-portrait of John Lennon hung over a table. “Even when we saw him that night we were like, ‘Oh shit, there goes KRS-One.’ We were excited, but he just looked at us like we were insane.”

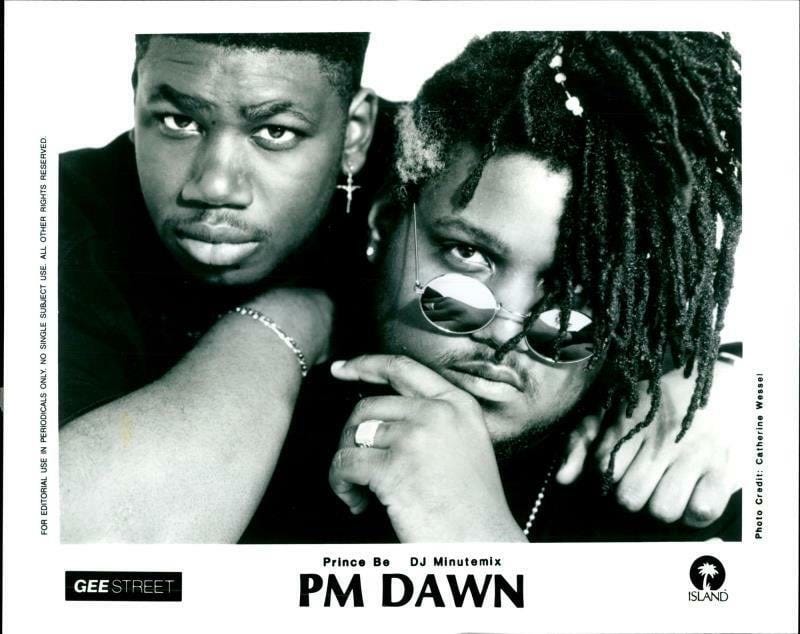

It was an MTV-sponsored event at New York’s Sound Factory nightclub. The eclectic duo was already onstage and had performed one song. The year before they’d released their groundbreaking debut, Of the Heart, of the Soul and of the Cross: The Utopian Experience. They recorded the album in England, where the brothers had relocated after signing with Gee Street Records in 1989. New York Daily News music columnist Jim Farber defined Of the Heart… as “a kind of soft revolution, critiquing the world by refusing any involvement. Instead they’ve proposed a kind of defiant hedonism, a purposeful apathy. For rap that’s a first: expressing rebellion through escape rather than anger.”

However, that night they played the Sound Factory, there was anger in the air. Just as P.M. Dawn were about to do their mega-hit “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss,” a track that sampled Spandau Ballet’s 1983 New Romantic plastic-soul ballad “True,” things quickly went askew. While the song was P.M. Dawn’s second single, following the trippy bounce of “A Watcher’s Point of View (Don’t ’Cha Think),” it was “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss” that became a major crossover smash and the first Black rap single to reach number one on the pop charts. Still, P.M. Dawn’s pop/MTV success did little to endear them the hard-core hip-hop gatekeepers.

While the perceived softness of P.M. Dawn’s music and Afro-psychedelic personas (Lennonesque shades, hippy beads, cloud-covered clothing) already made them suspect, it didn’t help that months before their Sound Factory appearance, in the pages of Details magazine, Be questioned KRS-One’s scholarly credentials (“KRS-One wants to be a teacher, but a teacher of what?”), which gave the rapper, along with his Boogie Down Productions posse, carte blanche to crash the duo’s set. Along with his brother Kenny, the two stormed P.M. Dawn’s set and KRS-One shoved Prince Be off the stage. Meanwhile, Kenny jacked the turntables and started spinning the BDP battle cry “The Bridge Is Over.”

Recording engineer and producer Scott Harding (aka Scotty Hard), who worked with the Cordes brothers at Calliope Studios, where he engineered the demo recording of “Reality Used to Be a Friend of Mine,” was at that show. Years later, he is still disgusted by what he witnessed. “Prince Be was a big guy, but he was like a teddy bear, so KRS-One found no resistance there,” Harding recalls. “It was a real invasion, and Prince Be didn’t deserve that. But, P.M. Dawn was blowing up, they had a pop hit and people resented that.”

Former Rush Management publicist Bill Adler, who had previously worked with alternative hip-hop/Native Tongue rappers De La Soul, was the Island Records press agent in 1992 and worked with P.M. Dawn on their first project. “When De La put out ‘Me, Myself and I,’ they clowned the limitations and aggressiveness of acts like Run-DMC,” Alder says. “But, Run-DMC merely brushed it off, while KRS-One lost his mind. But, he has always had a dual identity between having good politics and being a thug. I wasn’t at the show, but the next day the office was crazy and it generated a bunch of press. But it puzzled me that why so many people were taking KRS’s side.”

As though the beatdown wasn’t enough bad luck early in Prince Be’s career, diabetes sunk Be in a 3-day coma that same year, during what proved to be their longest marathon of hit songs. Diabetes hounded him his whole life.

“Prince Be was an early blurrer of the lines between rapping and singing, and between the earthly and the spiritual.”

Twenty-six years later, younger brother Jarrett Cordes says, “When all of that KRS-One stuff happened, it had a real effect on my brother. KRS could’ve pulled my brother to the side and talked to him, or anything else besides a physical altercation. Afterwards, Be even started calling himself the Nocturnal, because, he claimed it was a way to balance his positivity and negativity. All of that KRS stuff brought out a darkness in him that you can hear on tracks he made later that year like ‘The Nocturnal is in the House’ and ‘Plastic.’”

Both songs appeared on P.M. Dawn’s sophomore 1993 release The Bliss Album…? In an interview with Melody Maker that same year, Prince Be explained, “It’s like a documentary of what happened to me since the last album. I’m looking for the reasons for everything. I’d like an answer. To what, I have no idea. But I came up with no answers, no reasons. It’s called The Bliss Album sarcastically. The music is very out and laid back, but at times it gets to be real angry.”

Decades later, the KRS-One attack often seems to be more celebrated than the innovative music Prince Be left behind when he passed away on June 17, 2016, at the age of forty-six. Jarrett sang the P.M. Dawn soul hit “I’ll Die Without You” at Be’s homegoing services, shocking many in the church who didn’t realize that he had the chops. “Be and I sang together on many of those songs,” he says. “People just assumed that it was just him.”

Be’s underappreciated aural legacy can be heard in P.M. Dawn’s four commercially released albums, with Jesus Wept being my personal favorite, as well their remixes and outside productions for acts that included Elton John (“When I Think About Love”), Philip Bailey (“I Won’t Open My Arms”), George Michael (“Killer/Papa Was A Rollin’ Stone”), Cathy Dennis (“Falling”), Ambersunshower (“Running Song”), and a little-known rap group, Moodswingaz, that featured Be’s baby bro Jason.

Journalist Jon Caramanica noted Be’s New York Times obituary, “Even in an era of earnest bohemianism in hip-hop, P.M. Dawn stood out for its hippie-esque mysticism, fantastical imagery, crypto-Christian references and ethereal musical aesthetic. Prince Be was an early blurrer of the lines between rapping and singing, and between the earthly and the spiritual.”

When he was healthy, Prince Be was like a mountain with feet. Standing six feet four inches tall, he was a giant of a man with the talent to match. A welcoming collaborator in every aspect of P.M. Dawn’s music, he worked closely with everyone from the musicians to the engineers to the graphic designers. “I thought of P.M. Dawn as De La Soul meets the Beach Boys,” says writer Amy Linden. “Production-wise, Prince Be was like Brian Wilson, but without the mental illness and drugs.”

Still, while Be was the chief auteur behind their sound, he and Jarrett collaborated closely when it came to choosing samples. “A sample can make or break a song,” Jarrett says. According to the younger Cordes brother, it was his idea to use elements of the Gil Scott-Heron track “Angola, Louisiana” to construct “Paper Doll” and suggested the drums from the Soul Searchers’ “Ashley’s Roachclip” for “Set Adrift…” Jarrett laughs at the memory. “We always fought over samples, and with the planning of each album, we would break up. Jon Baker [Gee Street founder/president] used to call and ask if we had finished fighting. He’d say, ‘Can y’all brothers get your shit out so we can actually get some work done.’ He did that with every project.”

According to engineer Michael Fossenkemper, who worked closely with P.M. Dawn, “Be relied on Jarrett to get stuff on tape and to be another set of ears. Jarrett was instrumental and Be needed to have him around. I don’t think he could function without Jarrett around.”

“I think the songs should be interpretations of the emotions,” Be explained to me, “so we make the music first and, whatever the music brings out is what the lyrics are about. I’m like a kite and Jarrett keeps me from going too far out there. If I go way out there, I will either fall or keep going.”

In fact, no matter how much they might’ve argued about loops and beats, once the smoke cleared, the brothers realized that they were blessed to be doing exactly what they always dreamt when they was MTV watching boys. “We were just two kids from Lincoln Park, New Jersey, who came from nothing and literally made our way to be part of musical history,” Jarrett says. “We were brothers, so we fought and went through our stupid brother shit, but we also had number one records and got to work with our heroes. When we left Jersey for England, all we had was guts and a dream. I think that says a lot.”

In the beginning, there was MTV. Launched in 1981 when the Cordes brothers weren’t yet teenagers, the twenty-four-hour video channel started the ball rolling on the “second British Invasion” that introduced them to Culture Club, Duran Duran, the Human League, the Police, Depeche Mode, and Spandau Ballet. “When we became conscious of music it was the ’80s,” Prince Be said a few months before their third album, Jesus Wept, which critic Jim DeRogatis has called “a psychedelic masterpiece,” was released.

“I was an ’80s kid listening to Michael Jackson, George Michael, Prince, and Cyndi Lauper,” Be said, “but we were from an urban area and there was hip-hop everywhere. Some of the biggest innovations in music were coming out of hip-hop and we were witnesses to that.” Still, as much as they liked the new pop and hip-hop of the ’80s, Prince Be was always digging deeper and discovering the dusty sounds of Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, Harry Nilsson, Joni Mitchell, Sly Stone, Paul Williams, Brian Wilson, and Phil Spector.

“To me, my brother was Brian Spector,” Jarrett jokes. “He experimented a lot, because he never wanted P.M. Dawn to sound too normal.” A few years before our meeting, Island Records (Gee Street’s parent company) publicist Bill Adler gave me an advance of P.M. Dawn’s breathtaking debut. I assumed they were British and was surprised to learn that they hailed from Jersey right across the Hudson from me.

“My mom had six boys, so she worked a lot,” Jarrett says. “Somebody had to cook and clean, and that was me. Be would help them with their homework, and us being responsible for the kids made our bond that much closer. We started our first group with my uncle Tim, who called himself Courageous Cuts. I was Minutemix [an homage to ’60s cartoon Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse] and there was Prince Be. My uncle was in it just to have fun, but as Be and I got more serious, it became just the two of us.”

During those years, the brothers performed at house parties where Be gained a rep for being an awesome MC and a crazy beatboxer. Jarrett says, “He would have beatbox battles and just slay people.” It was during that time that the brothers decided to try to make records for real. “We actually sat down one day after school and talked about what we wanted to do with the rest of our lives. We were totally consumed by rap music and decided to produce some tracks. Prince Be was reading a religious magazine called The Plain Truth, and had seen the slogan that read, ‘In the darkest hours comes the light.’ Be said, ‘That’s phat. That’s kind of like P.M. Dawn.’ That’s how we got our name.”

Although the brothers were fans of everyone from Big Daddy Kane to future foe KRS-One, it was their love for the Jungle Brothers’ 1988 album Straight out the Jungle that gave them the courage to submit their cassette demo to the group’s label Warlock Records. “To this day, Uncle Tim is a garbage man, and he knew we were looking for different kinds of records to sample,” Jarrett explains. “One day, he found this crate of records that someone had dumped in the trash. We listened to them and found this Ruby Andrews album and found a sample on there that was just crazy.

“Back in those days, we didn’t have anything to sample with, so we used a cassette deck. We would just record little pieces of what we needed and paused it then did it again until we had this three-minute piece of sample. We did all those early demos like that.” The homemade tape found its way to the label’s A&R man Al “T” McLaran, who was undecided on whether he should sign P.M. Dawn. Al called his homeboy Ben “Cozmo D” Cenac, a founding member and producer behind electro rap group Newcleus whose “Jam On Revenge (The Wikki-Wikki Song)” was a hit in 1983.

“His philosophy was simple—he was just about peace, love, and making records.”

“After a while, Al decided to sign them,” Cozmo says from his home in Brooklyn, “but he needed someone to work with them in the studio, so that was my introduction to the group.” McLaran and Cozmo were also partners in Pet Project Records, a subsidiary of Warlock, and the label P.M. Dawn was eventually signed too. Located in Cozmo’s mother’s basement in Park Slope, Brooklyn, his Transitions Studios was where they recorded “Ode to a Forgetful Mind (It’s a Shame),” which was released in 1989. Cozmo remembers, “They were completely raw, they knew nothing yet. But, Jarrett only came to the studio one time. It was just me and Be doing all the work.”

Eleven years older, Cozmo adopted Be as his little brother. “He was only seventeen, but he was a big kid. At the same time, he was also very deep,” says Cozmo. “We would talk for hours, having these metaphysical conversations. He was into the Native Tongues and he wanted to meet those guys, but I told him, ‘You have to up [politically], because those guys are conscious.’ Be was the type of guy who would be conscious one minute and upsetting people the next. I tried to school him on the complexities of life, especially when it comes to the music business, but he wasn’t trying to hear that. His philosophy was simple—he was just about peace, love, and making records.”

The recording process went smoothly, though Cozmo does recall that when Prince Be told him he wanted to sing on the track, he laughed. “I said, ‘Man, you can’t sing.’ He insisted that he could, but it didn’t come out quite right. Later, I was shocked when they started releasing songs that were mostly singing. When I heard ‘I’d Die Without You,’ I was blown away, because I didn’t know he had those kinds of chops. We didn’t work long enough to get into an R&B side. Ours was strictly hip-hop, which he was dope as hell at doing. If he had decided to, Be could’ve been one of the all-time best rappers, because his skills were that good.”

In the meantime, McLaran got Jarrett a mailroom job at Warlock where Prince Be also hung out on the regular. It was in the office where they befriended labelmate and future collaborator Todd Terry, a dance-music artist and remixer whose energetic track “I Love the Way You Shake” they would later sample for their hip-house track “Shake.” Warlock/Pet Project released the 12-inch of “Ode to a Forgetful Mind (It’s A Shame),” whose label only had Prince Be’s name listed as the artist although Jarrett was credited as one of the producers alongside Be and Cozmo.

Unfortunately, Warlock did very little to promote the record. “Basically, they didn’t push it at all,” Cozmo says. U.K. partners Gee Street Records, who licensed the Warlock roster overseas, was having success with P.M. Dawn, getting their single radio spins and positive press. One afternoon when Gee Street president Jon Baker was visiting the Warlock office, he and Prince Be began talking about P.M. Dawn signing with his label. According to Jarrett, “Jon just told him straight, ‘Listen, I’m on your record more than Warlock is. You guys are awesome, but Warlock is not doing shit for you. I would like you guys to sign with me.’ Prince Be told me about their conversation and suggested we meet. Jon had already given him a [U.K.] magazine that was giving critical acclaim to ‘Ode…’and it was obvious he was busting his ass.”

Yet, somehow in the conversation, Pet Project Records owners McLaran and Cozmo were divided. “We were not moving any records, and Al wanted to sell their contract to Gee Street, but I was trying to start a new label called Black & Electric with P.M. Dawn as our star act,” Cozmo says. “Next thing I knew, Be said they were going to England. I told them they couldn’t go, because they were signed to me, but he just ignored me. We ended up with our lawyer signing over our rights to them. We got paid, but it was a bad separation. Be and I stopped talking for years. That happened in 1988, but we didn’t speak again until 2001. In the late ’90s, there was a P.M. Dawn website, and Prince Be would pop up on the forum. Eventually, I sent him a letter apologizing. Back then, he was a seventeen-year-old kid from Jersey struggling to get by. Really, I shouldn’t have blamed him for wanting to leave.”

The brothers were raised in a religious household, attended Catholic school, and sang in church on Sundays. That sense of spirituality spilled over into their music like forty days of rain, from The Creation of Adam/Sistine Chapel imagery of the cover of The Bliss Album to naming their third album Jesus Wept to Be giving out crosses to close friends and family. “I can remember him giving me a cross once,” says writer/filmmaker Vivien Goldman, who first met the boys in London when she was hired by Jon Baker to make P.M. Dawn’s video press kit. “I think we were at some gathering at Jon’s house, and Be gave me a cross that he designed himself and had crafted out of heavy silver.”

At the time Jon Baker was married to Ziggi Golding, founder of the Z Agency, which reps models and photographers. Vivian Goldman worked with P.M. Dawn to get the duo ready for prime time. Through it all, Be and Jarrett kept their spiritual side in check, never slipping down slopes of coke, weed, or sex. “They were not very worldly when they got to London,” Goldman continues, “and Jon and Ziggi took a caring interest in them. I filmed them a lot, but I was also their media trainer preparing them for interviews. Be was unconventional, but very natural and real, projecting a different sort of masculinity in living color.”

When I asked Be about his religious views, he answered, “Well, we both went to Catholic school, but I learned more about religion from going to the library. I used to play hooky and go to the library. For me, reading was better than going to school.” An avid reader, one of Be’s favorite books was Jonathan Livingston Seagull. “People always perceive Jesus as someone bigger than life,” Be said, “but they forget he was also a man. It’s that people are afraid to find religion within themselves. People have to realize that they are important to themselves and to each other. That’s the message I’m trying to get across. I found out last year that I have diabetes and all of that has affected me as an artist. In terms of life and death, I believe in reincarnation, I just don’t want to come back here.”

“Be was unconventional, but very natural and real, projecting a different sort of masculinity in living color.”

In the U.K., Black Brits Jazzie B, A.R. Kane (can’t nothing in the cosmos convince me that Prince Be didn’t spend hours in his flat listening to the dreamy pop of 69 through Bose speakers), and Loose Ends were encouraged to be different, and P.M. Dawn was on that same vibe. England was the perfect place for them to be free. Be developed a studio relationship with engineer/instrumentalist (guitar mainly, but also bass and keyboards) Tyrrell as they worked out of Berwick Street Studios in London.

“Right from the first session for ‘A Watcher’s Point of View,’ Prince Be and I got on extremely well,” Tyrrell remembers. “I had just turned twenty-three, and we were just kids left on our own. The first session was such a success that we booked in for the rest of the album over the next three months. Jarrett was only really called upon when Prince wanted scratching and cutting on sections of tracks. Jarrett was a real master on the decks.”

Although the brothers were new to London, there wasn’t much time for sightseeing. “Since our time in the studio was so precious, the boys would come to the studio right after waking up and not leave until after midnight,” Tyrrell says. “Prince Be had previously recorded demos of about half of the tracks, so he had an idea of some of the things that could be possible with sampling. I think my workflow speed and knowledge of the Akai S1000 sampler really opened his eyes a lot to new things that could be possible, which allowed for us to have much more creative freedom. Prince soon began to just play me three or four snippets off different records and asked me to make them fit together. He loved my ‘Paper Doll’ strings so much that every time after that when we wanted strings he’d say, ‘Let’s use the “Paper Doll” strings.’

“We were soon experimenting with guitar parts over some of the tracks, too, like ‘On a Clear Day’ and ‘The Beautiful,’” Tyrrell continues. “At first, he wasn’t too keen on my suggestion to layer many tracks of his voice [something he called the ‘Donny Osmond effect’] to create an ethereal vocal sound, but this soon became P.M. Dawn’s signature. I would layer eight or more tracks on every harmony then sample and re-trigger them through the track.”

After the worldwide success of “Set Adrift…,” the brothers were in France promoting Of the Heart… when they got a call from their management explaining that Eddie Murphy wanted to work with them. Although he initially wanted them to contribute to an album project of his own, their meeting led to Murphy asking them to create a song for the soundtrack of his then-upcoming movie Boomerang. “Eddie told us that L.A. and Babyface had the whole album locked down,” Jarrett says, “but, if we gave him a song, he’d make sure it was on the record.”

After returning to London, Prince Be summoned Jarrett to his room one night to share his latest inspiration. “Be was into Bobby Brown and Guy, but he had never written a straight R&B track,” Jarrett recalls. “But, when I got to his room, he said, ‘You’re not going to believe this shit, but I did a fucking R&B song. He started singing the song (‘Is it my turn, to wish you were lying here? / I tend to dream you when I’m not sleeping…’), and that was the beginning of ‘I’d Die Without You.’ We went to the studio [Strongroom] and started building the track with Tyrrell.”

“In the studio, he would just vibe out to the groove and next thing he would come up with a melody…”

Tyrrell recalls, “I was always trying to convince Prince Be to do a song without any sampling, so the music for ‘I’d Die Without You’ started just from the chords I did on a synth-pad sound. The melody and lyrics he wrote over top were so great, as was his performance. I built up the song with programmed drums, synth bass, and some electric guitar, then we wanted live piano, so I suggested a colleague of mine, James Barnett, to come in and put down some dreamy improvisations down the track. They even asked him to be in the video.”

Graphic designer David Calderley, who began working with the group with his stunning cover for “I’d Die Without You,” says, “Be was into the Storm Thorgerson album art for Pink Floyd, the Roger Dean paintings for Yes, and he wanted his own packaging to reflect that aesthetic. He had an affinity for the afterlife and cosmic experiences, and that became a part of the imaginary.” Calderley designed most of P.M. Dawn’s album, singles, and CD art during their Gee Street period, with his last commission being their greatest hits package. “Prince Be would tell me his thoughts and overview, and I’d take his words and try to make it into a visual story. The only disagreement we had was the Dearest Christian… [album] cover, because, originally, the album had a different title.”

Eddie Murphy’s soundtrack song “I’d Die Without You” came out so well, P.M. Dawn had considered saving it for their second project, but, according to Jarrett, the Gee Street/Island Record executives weren’t feeling it. “They said, ‘You guys don’t usually sing like that, where’s the rapping? You can give that shit to Eddie, we don’t need it.’ Of course, that record became a big hit and changed the sound of the group. After its success, we got a lot of flowers and apologies from the label. When we went to meet about the second album, they said, ‘We need more singing. We even want ballads, let’s get this shit going.’”

Returning to the Strongroom studio with Tyrrell, who also received credit for his musical contributions to the project, The Bliss Album was their last collaboration with one another. “I was pulled from the mixing session due to disagreements between our managements and lawyers,” Tyrell says. “This was a real shame, because Prince Be and I actually got on so well when creating together and I felt there was so much more we could have achieved.”

During the making of 1993’s The Bliss Album, Be decided he wanted different scratch sounds incorporated into the tracks “Beyond Infinite Affections” and “The Nocturnal Is in the House,” so he reached out to Philadelphia native DJ Cash Money and asked him to fly to England to work on the project. A few years before, the turntablist was signed to Sleeping Bag Records, where he’d released Where’s the Party At? with MC Marvelous in 1988. By 1992, he was spinning solo.

“Our mutual friend DJ Crash put us in touch,” says Cash Money, whose latest album, Street Cash, was released in August 2018. “I had seen the ‘Set Adrift’ video and I figured, ‘Ahhh man, let me go get this check.’ I thought they were going to be some spacey dudes, but we just hit it off so great. They were just regular dudes, and, when it was time for my studio session, I just went in there and knocked it out. I learned so much from Be about songwriting and layering voices. In the studio, he would just vibe out to the groove and next thing he would come up with a melody, build on that melody, and just start writing. He’d take it home with him and, next thing you know, he had a masterpiece.”

Cash Money and Prince Be became so close that the DJ was asked to become a member of P.M. Dawn, which involved him touring with them and remixing the “The Ways of the Wind.” The track was made into a video by a young Hype Williams. Film critic Armond White, who in 2006 presented the Williams retrospective Believe the Hype: An Auteur Study of Hype Williams at Lincoln Center, says of the video, “Hype is, of course, a genius. I can see what René Elizondo learned from that P.M. Dawn video (rhythm and color texture) and applied to Janet Jackson’s ‘That’s the Way Love Goes’ video the same year. Everybody learns from Hype.”

Be saw himself as a “sampling artist,” which meant that, like his new friend Cash Money, he was a crate digger who had a serious passion for record shopping. “We would go record shopping in London, but I knew a lot of the dealers personally, so we’d go to their house and buy records they didn’t have in the store,” Cash says. “Once, me, him, and Jarrett traveled for hours to a farm where the owner had the best record collection I’ve ever seen.” Jarrett, too, remembers the trip well. “The guy had the records inside of a barn, and the entire barn, every inch of the place, was covered in vinyl. It was unbelievable. I thought Cash was going to faint.”

Cash toured with P.M. Dawn, who had put together a band as big as Earth, Wind & Fire’s that included backup-singing women and percussionists, and also appeared with them on The Arsenio Hall Show, The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, and in the video for “Plastic.” “We shot that under some bridge in New York,” Cash remembers, “and it was cold as shit. First, my jacket caught on fire, then the pigeons shit on me. I guess it wasn’t meant for me to wear that jacket.” But, whatever city they were in, Cash knew where to buy records.

In New York City, Cash introduced Be to Roosevelt Hotel Record Convention where Q-Tip, Pete Rock, Large Professor, DJ Clark Kent, and countless others bought rare vinyl. If a bomb had fallen on that building back in the ’90s, New York City hip-hop would’ve been over. “I introduced Be to a lot of the dealers, and Be’s policy was never to haggle,” Cash says. “He paid whatever they asked. He had money like that. If a dealer asked a $1,000 for the record, he’d give it to them. No bullshit, he would drop like ten Gs on records. Pete Rock and all those guys would be mad as shit, because the dealers would be holding special records for him. When we first started hanging, he was buying a lot of Blue Note records, but I schooled him on other things the same way he used to school me.”

Writer, Ego Trip cofounder, and internationally known DJ Jeff “Chairman” Mao was a regular at the record conventions, and once sold Prince Be a copy of Mark Murphy Sings. “It wasn’t a rare record, it went for about forty dollars,” Jeff says. “There was a sense of resentment toward Prince Be from the other producers, because they didn’t understand what he was doing with all those beats. I don’t think many of them paid attention to his productions as well as all the songwriting and remixing he was doing.”

Although P.M. Dawn often used musicians, sampling was a major component of their sound. Being a student and buyer of such diverse music gave Be a wider palette when it came to sampling. “In many cases, sampling artistry is still looked at as thievery,” Prince Be said, “which was why we did ‘Norwegian Wood’ on the album.” The song was released as a single with a video directed by future Wes Anderson collaborator Roman Coppola. “It’s completely put together from samples,” Be continued, “but it’s a cover, so we didn’t need permission to record it. I think sampling depends on a certain level of creativity. When EPMD sampled [Zapp’s] ‘More Bounce to the Ounce,’ as much as some people thought that was thievery, I thought that was so creative, because of the way it was presented from a totally different perspective the original.

“Same thing with ‘Set Adrift...,’ because when it came out people said, ‘Them rap kids stole from Spandau Ballet.’ Even our record company thought we were a one-off until we delivered ‘I’d Die Without You.’ To me, you can’t be a sampling artist and not be a hip-hop artist. I would never exclude myself from being a hip-hop artist. I just wanted hip-hop to be bigger than it was.”

As much as Prince Be loved crate digging and recording, it equaled his disdain for being on the road. One night, he and Cash were in a studio in Los Angeles, and the DJ was supposed to drive them both to a show. “Be decided he wasn’t going to go, because his psychic advised him not to. The manager was begging me to get him to the venue and I had to push his big ass into the car. I had rented a [Nissan] 300ZX and I literally had to push his big ass into the car and do a hundred miles per hour to get us to the venue. Luckily, I was only ten minutes late.”

Released on March 23, 1993, The Bliss Album...? (Vibrations of Love and Anger and the Ponderance of Life and Existence) was another sonic marvel. “For me, the project possessed a dizzying array of aural vibes,” says critic says Quentin Harrison, “that includes funk (‘So On and So On’), hip-hop (‘Plastic’), pop (‘About Love of Nothing’) and contemporary soul (‘I’d Die Without You’).” It remains one of the boldest and most flavorful records of 1993.

Although P.M. Dawn could’ve gone anywhere on the planet to live and work, the otherworldly brothers returned to New Jersey. Prince Be married Mary Sierra and settled in a Jersey City penthouse where engineer Michael Fossenkemper built him a portable studio. Fossenkemperhad met the brothers the year before when he worked on parts of The Bliss Album at his then-usual home-base Chung King. “That studio was one of those places where everybody kind of went through there,” Fossenkemper says of the lab where Run-DMC, Brand Nubian, and RZA once recorded. “It was one of those places that many people ended up. It was popular in the hip-hop music scene.” Fossenkemper, who had worked with Color Me Badd, was known what he could do with vocals. “I think one reason Be liked working with me was because I had a lot of experience in harmonies and things like that. He really wanted to get more into that kind of thing.”

In the beginning of the relationship, Fossenkemper was a bit baffled by Prince Be’s work methods, not believing that certain samples or sounds would work or if his instructions were clear to the musicians. “After a while, I had to stop second-guessing him, because all his ideas worked,” Fossenkemper says. “I’m convinced that he had the whole song recorded in his head already. He just needed someone to help him mechanically put it together. When I build the portable studio, I had an endorsement with Roland and they came up with the DM-80, the first digital hard-disc recorder. It had eight tracks. I also had racks of samplers and a laptop with sequencing software.

“All his ideas worked.”

“Be toured with the studio, but most of time we were working out of his place,” Fossenkemper continues. “He converted a closet into a vocal booth. When you’re at someone’s house every day, you become like a member of the family. You watch the kids grow up, you’re there for family arguments and the happy times. Every once in a while, especially if he was producing for someone else, we’d go to a conventional studio. You couldn’t really ask Elton John to come to your house.”

While Prince Be worked hard on the 1995 album Jesus Wept, he and Jarrett were also in the studio with artists he once worshipped from afar. “When we were in the studio with [Earth, Wind & Fire vocalist] Philip Bailey, he was schooling us on how Earth, Wind & Fire wrote songs together,” Jarrett says. “Be and I would be sitting on the floor in the lotus position taking detailed notes. Then we were in the studio with Elton John working on his duets album. He thought Be was a great songwriter, so he gave us advice on how to further succeed and survive. When we worked with the Bee Gees, it was just weird having Barry Gibb asking us how we thought he sounded. It was weird, but we went there.”

Fittingly enough, P.M. Dawn’s cover of “You Got Me Floatin’” for the Jimi Hendrix tribute album Stone Free was recorded at the guitar legend’s own Electric Lady Studios. According to Fossenkemper, “Be got selected for that project because [former Hendrix producer and engineer] Eddie Kramer, who spearheaded the project, picked Be because he like the way he panned on some songs. Eddie loved panning.”

Releasing Jesus Wept in 1995, the brothers created an album inspired by heaven, love, and the afterlife as much as it’s influenced by the Cali pop, Prince parables, and the Greenwich Village era of Bob Dylan. Jesus Wept combined cool existentialism, religious symbolism, and romantic ecstasy, and was exquisitely recorded at their home studio. The experimental and loopy album was on a mission to take hip-hop to new heights no matter how much the world resisted. With its blaring guitars (courtesy of Cameron Greider), retro go-go flow, graffiti-covered walls of sound, layered vocals, trippy lyrics, and the Holy Ghost floating above, the entire album was like a Victor Moscoso–illustrated acid trip in Zap comics that took the listener around the world in a day.

Jesus Wept was also a testament to Be’s diverse sampling savvy as he mixed in beats ranging from Al B. Sure’s new jack “Nite and Day” swoon on “Sometimes I Miss You So Much (Dedicated to the Christ Consciousness)” to Deep Purple’s boogie “Hush” on the glam “Downtown Venus,” first single. “There’s a solo on ‘Downtown Venus’ that Be helped pull out of me,” says Greider. “It’s crazy and over the top, but I never would’ve played it without his direction. Because of his sense of architecture, timing, and phrasing. He knew so much about constructing pop music and was a master without having an instrumental ability.”

Meanwhile, showing that they could still swirl straight soul if need be, “Miles from Anything” has the appeal of a Delfonics/Thom Bell song while “Fantasia’s Confidential Ghetto” partially covers Prince, the Talking Heads, and Harry Nilsson while throwing in some Charlie Brown cartoon samples as well.

In a four-star Rolling Stone review, it was written, “On their third album, P.M. Dawn completed their transformation from a rap-based pop group to something altogether different and wonderful. It’s not that P.M. Dawn…don’t operate in the hip-hop arena. Indeed they do. But…the duo has taken the sound of hip-hop so far beyond rap that it would be simplistic to discuss its music in those terms alone.”

The album was released on October 3, 1995, but two weeks before it was due to drop, Jarrett was arrested on charges of aggravated sexual assault after allegedly having sex with a fourteen-year-old cousin. Although charges were eventually dropped due to lack of evidence, P.M. Dawn’s reputation was tarnished regardless of the rave reviews the record received. Despite what Prince Be, Gee Street, or anyone else tried to do, Jesus Wept was overshadowed by the devil’s mischief.

“For the record, my brother didn’t rape anyone,” Prince Be told MTV News in November 1996, “but my family is highly dysfunctional, which is the reason why I like to deal with the spiritual rather than the realistic.” Four years later, P.M Dawn released their last Gee Street album Dearest Christian, I’m So Very Sorry for Bringing You Here. Love, Dad, a disc that Entertainment Weekly writer Matt Diehl called “a truly ambitious pop album.” Unfortunately, the project sank like a lead balloon and P.M. Dawn was dropped from the label.

In 2000, the brothers released Fucked Music, an album released on their label Positive Plain Music and only available through mail order. A few years later, as Be’s sickness began to worsen, Jarrett began feeling as though he was having a spiritual crisis and left the group to return to church. Having met Reverend Run when P.M. Dawn performed “I’d Die Without You” at his wedding in 1994, Jarrett went to the former superstar rapper for guidance. It was during that period that their cousin Gregory Carr began backing up the group under the name Doc G.

In 2014, Doc G told me he was one of B’s caregivers and that he had trademarked the group’s name in his own name. It all sounded suspect to me, but as Anil Dash wrote on Medium.com, it only got worse: “Today, most of P.M. Dawn’s social media presence is maintained by Doc G, who also put out a handful of unremarkable releases using the P.M. Dawn name, with no apparent input from Prince Be. In the final half decade of Prince Be’s life, Doc G carried on the P.M. Dawn name (perhaps not entirely with the blessing of Prince Be’s family, depending on the accuracy of online rumors), while Prince Be endured a further series of health setbacks. Another stroke, dialysis, and a leg amputation all took a heavy toll.”

Since Prince Be’s death in 2016, Doc G has recruited a partner named K-R.O.K., and the two are conducting interviews and touring as P.M. Dawn. While this is a bizarre chapter in the book of P.M. Dawn, I doubt that this will be the end. Currently, Jarrett has been recording music for his purposed solo project, Back to My Roots, an album that will, in its own way, keep the musical memory of the original P.M. Dawn alive.

In the spring of 2024 someone wrote on Twitter, ‘If P.M. Dawn came out today they would be the biggest thing in music’” Although that sounds great, being ‘the next Michael Jackson’ was never Prince Be’s mission. The humble but brilliant man I met simply wanted to be appreciated as an artist and acknowledged—like J. Dilla, like Marley Marl, like so many of the greats—as someone who advanced the aural language of hip-hop, unafraid of taking the music one step beyond.

Note: A different version of this beautiful story originally appeared in Wax Poetics #68, in the winter of 2020. Republished here with the permission of author Michael Gonzales.

This is a great read. Coincidentally, I heard PM Dawn for the first time in years when I was at Petco a few weeks ago and was immediately a bit more joyful. I was also reminded of just how good they were. In a way, they were almost a "fever dream." They were just so unique, in sound, style, and feeling, almost to the point where it felt like they couldn't possibly have existed. They truly were ahead of their time and I agree with the article that they would've been huge if only they had arrived on the scene now. Anyway, great read and thanks!

Thank You for the great write up ! Much love 🙏🏽❤️