Selling Out

Nineties bands contended with harsh ideas about mainstream popularity and signing with major labels. Being a listener involved equally harsh ideas about being cool.

In the tiny Seattle clubs where Pearl Jam performed before Ten came out, some people in the audience felt magic.

“I was kind of in awe,” KISW disc jockey Damon Stewart said about Pearl Jam’s first show. “I just tried to soak it all in. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, that was different.’” Pearl Jam shot the video for “Alive” by playing the song three times at an August 3, 1991 show at RKCNDY. KISW music director Cathy Faulkner felt each version was more powerful than the last. “I was crying,” she said. “I was just crying because there was so much energy, such a rawness. You knew you were part of something special.” Vedder liked to hang from that club’s rafters. Maybe that power diluted once Pearl Jam took their show to arenas and had played those songs too many times, but watching them play a giant, echoey sports arena in December 1991, my friends and I felt something special, too.

When we bought those concert tickets, I didn’t understand much about the music industry. I was 16. We just wanted to see good bands play. Looking back, it’s interesting what my teenage perception of early Pearl Jam reveals about notions of underground culture verses mainstream culture and the very dated idea of “selling out.”

A kid’s view of the world is small. Early ’90s kids were far less woke than kids today. We knew about saving the whales and rainforest clearcutting, but economic exploitation and social justice were not big enough parts of the cultural conversation to reach many of us white middle class kids yet. Even as teens, we mostly saw what was in front of us. In capitalist America that meant we saw products more than production. With the music business’ many wizards hidden behind the proverbial curtain, our music could sound pure and our musicians could be artists, or better yet, superhumans.

Hearing Pearl Jam’s “Once” for the first time, blasting on our friend Jessica’s speakers while her mom was at work, the band seemed so powerful, so underground. It turns out, that was only because our parents and the jocks at school hadn’t heard of them yet, not because they were an indie band. Unlike their basement rehearsal space, Pearl Jam was never “underground.” Thanks to members’ Love Bone days, they had major label interest since they’d first recorded those “Stone and Co.” demos in 1990. Talent coupled with drive and existing industry connections got Pearl Jam signed quickly. Vedder first flew to Seattle on October 8, 1990. They recorded Ten during March and April 1991. Epic Records released “Alive” as their first single on July 7 and released Ten on August 27, 51 days later. Although Pearl Jam briefly played small clubs like any new, emerging band, they were never some struggling emerging upstart like many of us thought they were. This kind of trivial thing was important in the early ’90s.

Once the manufactured term “alternative music” started gaining traction, businesses started selling us alternative music, and it was our job to recognize the fakes from the true alternatives. Pearl Jam got picked on a lot.

“There are a lot of really mainstream bands, who sound just like Poison or resemble Poison very much,” Kurt Cobain once said, “and they’re being promoted as alternative bands. I find that really offensive. I think one of the biggest examples of that would be Pearl Jam.”

“We were coming from a punk rock standpoint,” Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl told Spin. “And Pearl Jam might have been as well. But we wore it on our sleeve a little more heavily than they did. Kurt had made his opinions known: ‘How could you consider Pearl Jam alternative?’ Because their music had, like, guitar leads or whatever. It was pretty ridiculous. And the thing that was so funny to me was that it seemed Kurt and Eddie would have gotten along really well.”

“The media was kind of trying to make Pearl Jam and Nirvana diametrically opposed to each other,” said Mudhoney guitarist Steve Turner, “like Nirvana’s the real deal, Pearl Jam’s the made-for-TV kind of band. Even Cobain was saying that.” Others parroted this idea.

Time magazine’s October 1993 cover story was titled “All the Rage: Angry young rockers like Pearl Jam give voice to the passions and fears of a generation.” Featuring a screaming Vedder on the cover, the story explored alternative music through the lens of Pearl Jam’s success and the third Lollapalooza. “And therein lies the controversy,” wrote Time, “alternative music is currently one of the most potent forces in the mainstream, which has triggered an identity crisis and rancorous debate among musicians and fans. If these rockers are stars now, fans ask, haven’t they become everything we’re against? Nothing better symbolizes the struggle for this musical genre’s soul than the success of Pearl Jam, a band adored by followers but reviled by some fellow musicians as sellouts, poseurs or opportunists riding on the fame of their fellow Seattleites, Nirvana.”

“When me and Jeff were at Sub Pop [with Green River],” said Pearl Jam guitarist Stone Gossard, “we left in our wake a rift. That rift was what Kurt attached himself to, and it was perceived in the media as this huge line in the sand. I remember feeling blindsided by that, particularly because when I heard his record, it sounded so good and so immediate, I wanted him to like our band. That stressed everybody out. He crystallized a negative viewpoint of the band. I think all of us didn’t know if we deserved the hype aspect of what was going on. Why me? I know fucking a hundred great guitar players. What am I doing that’s different? There’s a lot of that mindplay that starts to come into existence once we do well.”

“Mark Arm in particular was bitter about us leaving Green River,” said bassist Jeff Ament. Ament and Gossard had played with Arm in the underground sludge band Green River before forming Mother Love Bone and Pearl Jam. “Then I heard what he was saying about us. That’s kind of what started the whole ‘Jeff, in particular, and Stone, being careerists’ thing. The fact of the matter is, in Green River I was the only guy who had a job. Those other guys, they had trust funds, were getting financial help from their parents. I was the one who was hungry to have my rent paid for. With Kurt Cobain, that’s what got misconstrued. Maybe I was the one who wasn’t going to get bailed out by anyone if I was 30 years old and still working in a restaurant. I was paying back student loans. Those things that Mark, or Kurt said, they hurt quite a bit initially. It was almost portrayed like at a young age I decided I was going to be a rock star. And that definitely wasn’t the case. I made several attempts to talk to Kurt and he would put his head down and walk away. I’m sure some of it was based on them getting asked about us. We were getting asked about them a lot, and you get sick of it.”

Selling out, stardom, being a corporate shill—these were divisive issues back then. Generally speaking, bands sold out if they signed with a major label to cater to the masses, or got too popular. Sellouts were traitors who’d betrayed certain principles for money. In the early ’90s, you heard this derogatory phrase constantly: They used to be good but now they suck. They sold out. Or redemptively: Majors came knocking, but the band ignored them because they refused to sell out. This idea formed the root of many alternative rock values about what was real, what was good, who was an artist and who a poser. It shaped listeners’ tastes. Yeah, people would say, I liked their early stuff, meaning, liked it before it was commercial enough for you to hear. Selling out was all about visibility, mass consumption, and bands’ financial objectives. It was as much a part of the lexicon as ‘aiight’ and ‘bling,’ except with a longer shelf-life.

In the ’90s, journalists constantly asked musicians about signing to major labels and getting popular. It was a reflex, like asking “How are you doing?” instead of saying “Hello.” When the free music magazine New Route asked Meat Puppets’ bassist Cris Kirkwood “if they worried about getting popular for the wrong reasons now with a major label pushing their most obvious hard rock qualities,” Cris said, “Naah, I mean we already got signed for the wrong reasons. To say what’s right or wrong is going to put me in punk rock land. I’m not that. So to say, ‘the wrong reason’ would imply that there are right reasons to be signed. …We don’t stop at the rock boundaries at all, or the human boundaries.” Other times, reporters smuggled in their opinions. When Depeche Mode played Phoenix’s huge Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum in 1990, one local paper wrote “Can you still call it alternative music if it fills the Coliseum? We’re not sure, but it’s a good beat and it’s easy to sulk to.” It’s a good question about the era’s “alternative music” label, but DM had been playing arenas for years, including the famous Rose Bowl two years earlier. Who said DM was alternative? Whatever. The dichotomy was clear: Major labels ruined good music by marketing it to the masses, and anonymity was purer than artistically vacuous success. Why get in bed with capitalist pigs? The dudes in suits who ran major labels from skyscrapers were the same people who called the cops on your teenage house party and kicked skaters out of the mall parking lot. Fuck those people.

Part of this was the era. During this period in American music culture, capitalism had run amuck. Once Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” hit big in late-91, corporate label talent scouts searched clubs for the next Nirvana and Pearl Jam—scouts, who some people imaged as mullet-headed squares who only wanted to make money off your band but didn’t get you at all, or care to. Music magazines and MTV overflowed with stories of bands making it or failing to, of hometown darlings and indie stalwarts, of big label hopes and big label advances, of bands who shot expensive videos trying to “crossover” from tiny clubs, and of surprise Billboard hits “that couldn’t have happened to a nicer band.” Even when teens missed the nuance and understood it in stereotype, we couldn’t miss all this blatant business activity. Of course journalists asked bands about major labels and popularity. This was the story of the time. Big labels changed the soundtrack of America. During the 1980s, underground bands and independent labels had fostered a thriving universe of bands outside mainstream radio and TV. Really good bands suddenly had opportunities to be heard, and listeners were able to discover different kinds of powerful underground music more easily. That made that time exciting. “Back in the early ’90s, there was a sense of urgency,” said Nine Inch Nails guitarist Brian Liesegang. “It felt like it was the ’60s again.” But capitalism became a vacuum sucking musicians out of underground scenes across the country. This was what people considered the music industry’s last gold rush. One response was to reject capitalism and fetishize purity, smallness, independence, even failure, and celebrate those who managed to stay underground. Anyway, there were countless reasons to watch out for success.

Rock ‘n’ roll has always ruined people. While rock culture and the music business can foster creativity, they also inject people with a potent speedball of money, access, encouragement, protection, idle time, unbearable pressure, ego stroking, criticism, infantilism, and fuel for delusion. America builds you up and enjoys tearing you down. Rock encourages immaturity then punishes bad behavior. It takes a strong personality, a tight group of friends, luck, and age to navigate all this and still manage to create new music.

Trent Reznor descended into addiction early in Nine Inch Nail’s success. Touring for their second studio album The Downward Spiral, which was their breakout album, they called their tour The Self Destruct Tour. “On that tour, I was a mess, quite honestly. This was the peak of Nine Inch Nails’ newfound rocket ship of fame,” Reznor told Rolling Stone. “It distorted my personality and became overwhelming: to deal with having everyone treat you different, to going from not being able to afford a gas bill to show up to arenas full of people, who kind of think they know you. The line starts to blur between the guy onstage and the person you used to be.” Fame doesn’t destroy everyone. But Reznor initially believed that music and live performance would provide cathartic creative outlets that would let him expel the “rage and self-loathing” that filled him at that age. “I thought I could get through by putting everything into my music, standing in front of an audience and screaming emotions at them from my guts,” he said. It didn’t. Because, in his words, “I wasn’t equipped to deal with any sort of the weirdness of fame. Alcohol, drugs and what not became a tool to help cope and did for a while until they didn’t.”

In the Ministry documentary, Fix—itself a study of pitiful excess and impressive creativity—Maynard from Tool discussed this issue: “If all of the sudden you’re selling a million records, and you’re 22, that’s going to affect you. You’re going to believe your own press, and you’re going to become the person that you’re being told to be in print, and with everyday ass-kissers and yes-men. You’re going to become that monster. You see it all the time. The guys who get popular when they’re 21, 22, 23, they’re the worst. They’re just monsters.” Maynard was grateful that his bandmates formed Tool in 1990 at the more stable ages of 27 and 28, when their cerebellums had developed enough to handle success’s demands. (He also credits military experience for providing certain adaptive—ahem—tools.)

And of course, after a few intense famous years, 27-year-old Kurt Cobain was done. He held ideas about artistic authenticity which conflicted with the complicated issues of fame, aging, and success. He quoted Neil Young in his suicide note: “It’s better to burn out than to fade away.” Had he lived, Cobain would’ve eventually shared the elder Young’s career dilemma about staying connected to young listeners while presenting yourself and your beloved back catalogue to the world in a dignified way. You didn’t want to be The Rolling Stones, who’d written incredible songs but become caricatures, overstaying their welcome. But you couldn’t neglect your adult financial responsibilities either. The bills complicated the optics, even as the joy of playing music could make retirement unappealing.

There were plenty of artistic reasons not to sign to major labels. Corporate relationships bring heavy pressure and obligations which can change the music. Expectations can hamper the same creative freedom that got the band signed in the first place. “It starts going through those channels,” Eddie Vedder said in the 1996 documentary Hype!, “those money-making channels, everything changes.”

There were also financial reasons not to sign to major labels. Corporate labels could pay big advances. They had marketing muscle and relationships that got bands on MTV, radio, late night talk shows, and big tours. And as Mudhoney mocked, didn’t you want your very own spotlight just like some real rock star? But corporations were also scummy. They abused power. They exploited third world laborers, wasted natural resources, and polluted the environment. They used intimidation, lawyers, and dirty tricks to squash their opponents—all for profit. How could musicians feel good taking dirty corporate money? And why feel safe making a deal with the devil? If musicians didn’t earn back their advance, they could end up thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of dollars in debt, which was worse than the obscurity big labels could rescue bands from. In their search for the next Nirvana, big labels didn’t necessarily care about bands’ lives. They cared what sold. If a band’s music didn’t sell, well, they often got dropped from the label, because business is business. Early on, even Nirvana feared getting dropped. Along with debt was the personal burden of failure, which is a story that everyone would hear thanks to MTV: You tried. You failed. Your album didn’t sell well. It’s back to doing bad Eddie Vedder impressions inside dingy bars for you, The Nixons, except with debt. Maybe the disappointment got to one-hit wonders like Dishwalla, and they fell into the drink or took their life, like Material Issue’s brilliant lead singer Jim Ellison did in 1995. (God, Ellison’s band was good!) Then the purity police could mumble Told you so. But if you kept the proverbial bar lower, you could never fail, and you could keep your day job and keep playing local clubs and drinking beer with your friends, as low-key as you always had. No harm, no foul. But wait, was that success or was that failure? That depends who you ask.

Selling out wasn’t simply about rejecting big business and fame. There was a lot to embrace about the musical underground. The culture that got labeled “alternative” had long provided a fertile environment where artists could find themselves musically and personally. Outside of the spotlight, free of corporate pressure, musicians could experiment and explore. As Smashing Pumpkins’ singer Billy Corgan told Time: “[In] the beginning, at least, it seemed to me that I could be whoever and whatever I wanted to be.”

“I don’t like labels,” Jane Hatfield said about the alternative music label. “But if you want to put me in that category, it’s O.K. with me, because being labeled alternative has a certain amount of respect that goes along with it. It means that you’ve started out on your own, the ethic of doing everything yourself.”

Indie bands had long taken pride in doing things themselves: writing their own music, recording their own albums, finding a label who appreciated and supported their vision, and booking their own tours. Their musical life was their thing. They made it, uncompromised. We ’90s listeners were forced to grapple with these issues, too.

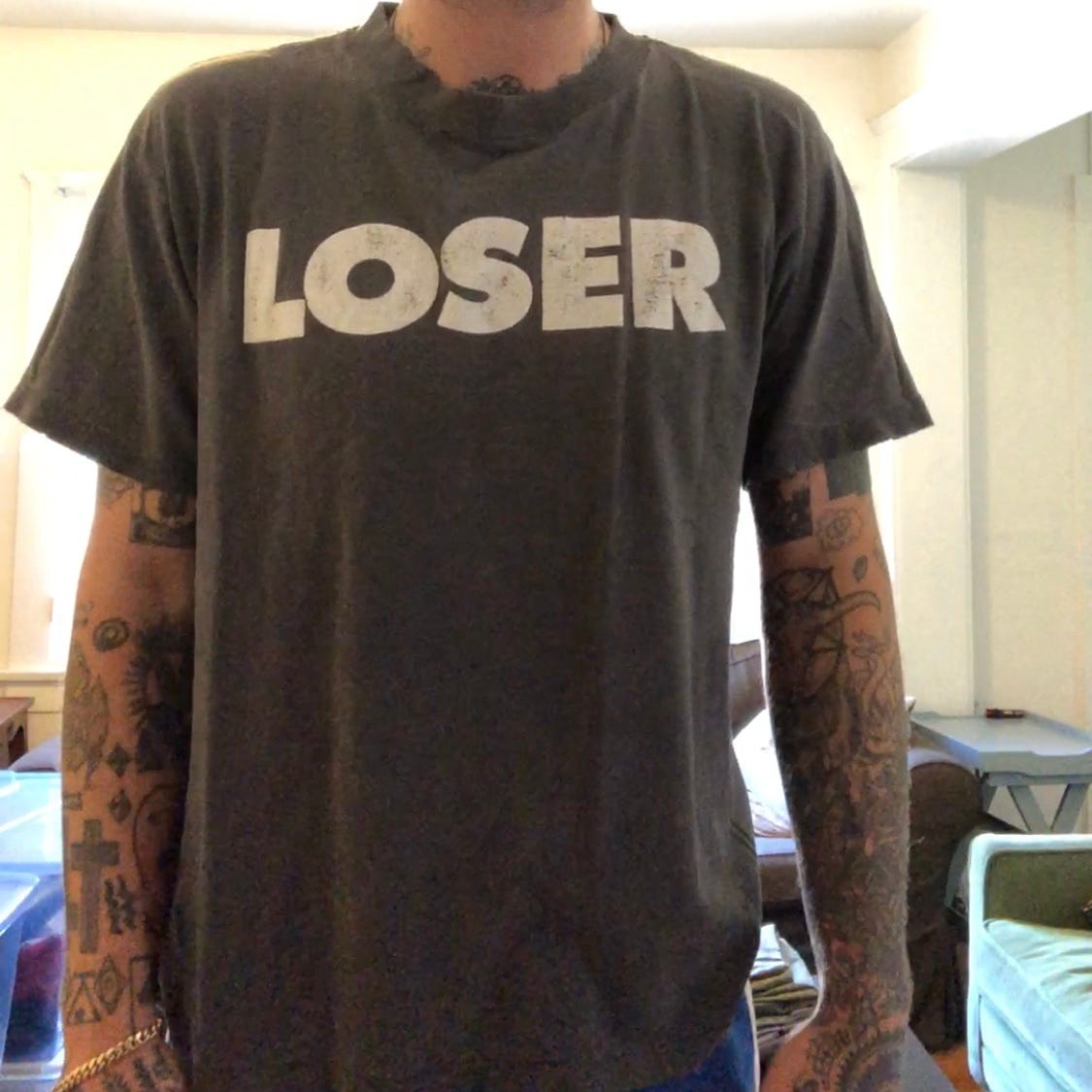

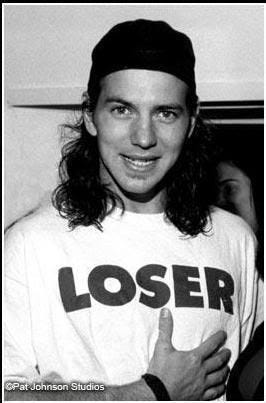

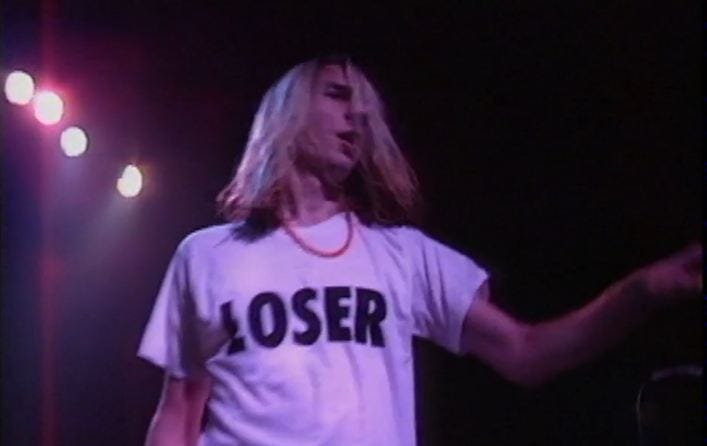

I’m no expert on the band experience, but having lived this as a listener, selling out put you in a bind: If Gen X was supposedly the slacker generation, that was partly because we couldn’t appear too ambitious. Otherwise we were no better than our Boomer parents, and we weren’t supposed to want that. Supposedly the ’80s sucked. I was in elementary and middle school, so what did I know? The punk we listened to as kids raged against Reagan and ’80s economics so much that albums constantly had Reagan’s face on them, and nukes and dollar bills. If you defined yourself in opposition to your parents’ adult world, then you had to reject certain trappings of their lives. Supposedly that included ambition? It didn’t seem as clear in practice as historians make it seem in retrospect. I mean, we didn’t slack more than kids inherently do. We skated, biked, hiked, went to shows, built dirt bike tracks, drew, made covers for mixtapes, collected flyers, and records. It’s not like we lived on the couch. This slacker label is too broad a brushstroke to paint any generation with, but somehow in the ’90s, ambition got so linked to corporate entities, tribal loyalty, and the idea of “corporate things,” that ‘corporate’ became a derogatory term, and musicians were held to a certain standard defined by the idea of authenticity and how they earned their money. How could you sport that classic Sub Pop loser shirt if you were winning big? Cobain should not have cast stones, but that’s partly why stones appealed: He projected his own issues onto Pearl Jam. He had become commercial, and he railed against them for that. Therapists call this projective identification. Cobain was in a bind.

Cobain was a hugely successful punk rocker, a millionaire with K Records values who hated the trappings of fame but appreciated the large musical platform and lived in the kind of gorgeous lakeside mansion that his talent deserved. But he struggled to have it both ways: punk values, mainstream success. He tried to manage the optics with little gestures like writing “Corporate Magazines Still Suck” on the white t-shirt he wore on the cover of Rolling Stone. When bands got dragged over to the other side, then they had to deal with public perception. Raking in too much dough on a lucrative major label sounds pretty sweet when you share a tiny rental with smelly roommates and wash dishes for a living, but big bucks also made your shirt ironic. Irony was also very popular in the ’90s. The line between irony and reality blurred hard in the Frankenstinian corporate-indie world that Sub Pop created. Tongues stayed planted in cheeks, but those tongues’ owners were trying to make the cash registers ring, too, which seems to describe Cobain’s difficult situation as a successful subversive, and helps explain his beef with Pearl Jam. To be true, you couldn’t win too big, so you couldn’t let people see you try too hard. Sure, play shows. Make a name locally. Be your town’s coolest band, but if you reach too far beyond that, people with these values could turn on you. Don’t be like those corporate flunky hairbands on MTV. If you even aligned yourself with certain elements of mainstream culture and capitalist economics, you had been compromised. Traitor. Sell out. Actual loser. You had to stay less visible. There in the underground, cool people could still see you. Sure, indie labels didn’t have the staff or money to print enough records or reach the right customers, but at least some kids could hear your music. At least you weren’t the clown dancing shirtless on MTV, or in Mudhoney’s words “up there, shirtless and flexing / Display of a macho freak.” You still worked at the restaurant and shared an apartment, because that’s what real artists do. To win with the subculture, you didn’t have to necessarily lose, but you at least had to struggle and maintain a certain medium level. And the subculture were the votes that mattered. Those were the cool people, the young people, the interesting people to talk to at parties. Didn’t you want to be cool?

Although my friends entered our adolescence in this confusing environment, the idea of selling out had existed for decades.

“The use of the verb to sell to mean ‘to betray’ is as old as the English language,” writes musician Franz Nicolay in Slate. “The Oxford English Dictionary cites examples stretching as far back as the 10th century. …The OED’s first citation is a private, colloquial use in a Civil War–era diary, in which the Southerner Mary Chesnut lamented ‘Another sellout to the devil.’” But American leftist politics started to change the phrase’s pejorative usage in the late 1950s when, Nicolay writes, an “anti-corporate usage became concentrated in the emerging labor union movement, paranoid about loyalty. ‘You, as a Communist party-liner, probably think I am a softie, a sellout to the capitalist world, a Trotskyite, a rat, et cetera,’ wrote critic John Chamberlain in a book review in Scribner’s magazine in 1938.” Nicolay’s enlightening article highlights the value people placed on loyalty. In music, the term referred to good ticket sales, since it was good business when no tickets went unsold. That changed in the 1950s, when the phrase “appears to have been first applied to musicians by black audiences and fellow musicians criticizing black gospel and jazz performers,” he writes, “who were perceived as having tailored their acts to appeal to white audiences. Reflecting later on the commercial successes of saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, jazz critic Doug Ramsey wrote, ‘Cannonball was subjected to the standard abuse of jazz artists who win public acceptance; he was called a sellout. Show me a solvent jazz band and I’ll show you a band accused of selling out.’”

Mid-century jazz’s conflation of popularity with musical quality carried over into folk and rock culture. Folkies damned Bob Dylan as a sellout for going electric, and The Who tried to take the sting out of the term with their 1967 album The Who Sell Out. That conflation maintained agency into the 1980s when, Nicolay points out, artists addressed this openly:

In one 1989 edition of Musician magazine, one could find both Tone Loc and the Replacements defending themselves against the charge. “People get panicky when you’re not their little pocket group anymore—their favorite little group that only they know about,” said the Replacements’ Paul Westerberg, “People panic whenever things change,” added guitarist Slim Dunlap. “If you try and stay pigeonholed and please the old fans, that’s the kiss of death. You can’t please everybody. But we didn’t sell out, I know that … What is a sellout, anyway?” Already, exhaustion with the term had begun to set in. In 1984, Harper’s called it “an old Stalinist term, redolent of class struggle.” By 1989, one letter-writer to the fundamentalist punk zine Maximum Rocknroll had grown sick of it, even as the editors and contributors circled their wagons: “One of the most obnoxious terms around has to be ‘selling out.’ This along with ‘trendy’ needs to be retired. If a band that is considered ‘underground’ gets played on a big city San Francisco radio station then they’ve ‘sold out.’ That’s really weak.”

Or in ’90s parlance: That’s weak sauce. Yet during the ’90s that idea gained traction. Besides the era, maybe this had something to do with listeners’ age.

Although Fugazi, the Riot Girrl movement, and indie labels like Dischord and K operated according to strong, thought-out values, there didn’t seem to be a clear punk or anti-capitalist ideology beneath the general idea of selling out. It was more reflexive, and it blurred with a teenage ideology. That makes sense. Selling out’s plot points parallel the narrative of adolescence, built around fixations about popularity, the social hierarchy, and how kids change. Teenagers are obsessed with rank and change. She’s popular. He’s a loser. As they grow, they change styles, change friends, change schools, change their tastes, even change how they talk. Others notice. They point it out, tease you, or at least hold you accountable. In ’90s terms: What, you think you’re all that and a bag of chips now because you made rich friends? Or: She used to be hella cool until she met Alissa. Growth often moves teens further from their past style and old friends, which breaks allegiances, violates certain codes, and disappoints people. Kids go from average to cool, from geeky to sexy, from regular to popular, from goth to pink mall rat, from shy high school hiker-type in a hemp choker to rowdy college frat boy in a hemp choker, from college rock ‘n’ roller to boring middle-aged banker. Major labels were signing countless underground bands in those bands’ youth. With media stories centered around record deals turning nobodies into somebodies, you can say that the theme of the early ’90s itself was growth, hype, popularity, change. Music echoed teenage life. It’s like Cobain sang: “You’re in high school again!” Bands were going from your teenage secret to everyone’s darling, and in the process of reaching your little brothers’ ears and your parents’ lame friends, bands’ growth threatened what you liked about them, because part of what you liked was your hold on them. They were yours, but like your friends, they were changing. That was uncomfortable. Bomb bands were no longer fly. (Did I used those terms correctly?) They were buggin’, so it was time to bounce. (I’ll stop now.) Bands’ popularity felt like when your close friend got a serious boyfriend or girlfriend, and you didn’t see them as much as you used to. Traitor!

This petty stuff mattered because when you’re young, music stands for something. It represents your independence from your parents, your rebellion against social norms, your outsider status. Music is the way you define yourself in opposition to the adult world and convention. It represents how tough, tender, depressed, angry, or nihilistic you are. It bonds your friend group. It designates your identities, your personalities, all that you are and all you’re trying to be, including your tribe: goth, rebel, skater, artist, jock, queer, computer programmer, band geek, sorority sister, class president, Mr. Nobody, or Mr. Popularity. Music makes a statement: Fuck you, I’m me, defiant and free. Or: Hello, I’m me, who’s just like you, a sheep. The Circle Jerks’ song “Wild In the Streets” always struck me as a fitting anthem. I didn’t literally run wild in the streets, smashing car windows or beating on mailboxes, but I was wild at heart, thinking myself irrepressibly individual, a sovereign state outside mainstream America, and I liked that song title’s message more than the music. Music was personal.

When author Michael Azerrad borrowed the Minutemen’s lyric for the title of his book Our Band Could Be Your Life, he recognized the role music plays at the center of our youth, how popularity and commercial success were one barometer of a band’s importance, and that personal relationships were a more important barometer. Like guitarist D Boon who wrote that lyric, Azerrad knew the absolute cosmic importance of music for young people. You don’t mess with that. It’s sacred. It’s who we are. The band unit itself was the glue that held together D Boon’s and bassist Mike Watt’s friendship, just like music and going to shows was the glue holding together me and my friends’ relationships. Music was bigger than music. It was life.

Some friends play sports. Some spend their time playing D&D or wrenching on cars. We went to shows. Music fused us. If a band we liked came, we went. It didn’t matter how far the drive. My friend Jim and I drove four hours roundtrip to Tucson to try to get into Alice In Chains’ sold-out April 1993 show at the Tucson Convention Center. No one would sell their tickets, so we listened to a few songs through a gap in a loading door behind the venue—just booming reverberations over Layne Staley’s voice—then we drove home. It was awesome. The previous year, our crew saw the Beastie Boys play their Check Your Head tour in Mesa, Arizona, then we drove to Tucson to see it again three months later. When Faith No More opened for Guns N’ Roses and Metallica on a notorious package metal tour that had caused a riot in Montreal weeks earlier, we drove way the hell out to Phoenix International Raceway on the edge of town. The stage was as big as a barge. The heshers aggressively pushed us Faith No More fans in the pit. The line of cars was so huge that it took four hours for some people to get in, and some tried to walk across the flooded Gila River to avoid traffic on the way out. One teenager drowned. Authorities rescued eleven others. Since we left during Metallica, we only heard about it the next day. Our entire adolescence looked like that: show after memorable show. It seemed like we saw one every other weekend. At one point we realized we’d seen The Rollins Band five times in less than two years.

This is why it was so offensive when so-called alternative music went mainstream. If selling out violated some peoples’ principles, it also violated many kids’ sense of self. It’s so corny to say that as an adult when you have perspective—especially as I write this during a pandemic—but as I said, kids’ worlds are smaller. Rebel kids laid a territorial claim on music. Music was us versus them. This was our music. That was your music. That’s how cool we thought we were. We weren’t jerks about it. We were fun-loving, jovial guys who were constantly laughing and making friends, but our musical taste gave us an elevated sense of rank. When mainstream America started to like our music, cool bands could became lame bands, even when those bands still sounded good. As Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein put it, “I never was quite able to look as much a freak on the outside as I felt on the inside.” I felt that way in ’91 before my hair grew out. But cool music gave me the confidence to take this Moses-on-the-mountain posture while I dressed like a dork during my gangly, zitty, early Catholic school days, when I paired plaid surf shorts with DM shirts with Birkenstocks and black socks in a total WTF ensemble, and while my hair remained the shortest among my friends. We were in the know and had a glow.

Teens often turned on music just because it “caught on,” no matter how hard it was to let go. As the Alternative Era progressed, the people many of us freaks defined ourselves in opposition to—the jocks and meat heads, hippies, heshers, and hicks—started to like our music, but we always found new bands that hadn’t caught on, or bands that were too abrasive, sophisticated, or weird for the masses. Cliques existed. Freaks were freaks. Jocks were jocks. But as underground culture got commodified and sold to the masses during the early ’90s, the worst thing happened: Jocks eventually started thinking they were cool. When they started to know cool bands from MTV and started to grow out their hair like those bands, they actually mistook themselves as a more subversive, left-of-center breed. To us, they still acted like small-minded dicks who spouted racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-Semitic trash. Our clothes weren’t what ultimately divided us. It was how we thought. They bought what was sold to them, and subculture was the new commodity. You couldn’t dress yourselves out of small-mindedness. For kids like Cobain and Novoselic, rednecks were the face of this. “[R]ednecks weren’t just dicks,” Novoselic said, “they were total dicks.” For me it was jocks.

Just as they always had, the jocks at my all-boys catholic high school operated according to the group-think embodied by their beloved team sports. To me, teams were sheep. I didn’t play team anything. I liked to think that no one told me what to do, even though people absolutely did. Meat heads may have been A-list in the small ecosystem of school, but when they saw real subversives who took risks and favored independence, meat heads had to see that they weren’t objectively cool like that. They were peaking in high school. They liked cock rock. They called Jews like me kikes, and called soft kids queers, and if you didn’t like macho, chest-beating rock bands like theirs, you were probably queer, too. Social strata marked everything as a teen, but we thought they were a joke, just like their music. When one jock said someone “tried to Jew” him then mumbled “But, sorry Aaron, you’re not like that,” I went off, getting in his face and threatening to beat him physically the next time he said that—even though I’ve never beaten anyone physically—and he never said that again, but it was clear that’s what mainstream white dude culture was all about, and we weren’t that. We questioned authority, related to outsiders, skated, drank beer, smoked cigs and weed and took acid, and did what we felt was best for us, even when it did damage. Suddenly they liked Nirvana and had transformed their essence? Not a fucking chance! But that’s how it went.

The early ’90s were a period of massive cultural transformation, where what was once the subculture became mainstream. This was a national phenomenon, and my friends and I were one of millions of kids who now had a way to feel superior to somebody. Like jocks, the existence of sellouts let insecure youths like me feel cooler than you, by validating our loyalty to our own outsider herd. And sadly, that change was inadvertently ushered in by Nirvana’s popularity, a band led by a guy who wore dresses on stage and was outspoken about feminism, punk ideas, racism, and gay rights. In Our Band Could Be Your Life, Azerrad said Cobain lashed out at the “jock numbskulls, frat boys, and metal kids” who now attended his popular band’s shows. In fact, as much gibberish as they contain, Cobain’s lyrics to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” are a skewering of college meathead party culture, aimed specifically at the jocks he felt ran counter to his values. The music was a Pixies rip-off—getting loud then going quiet again—but the song mocked bland mainstream culture, even rock itself. That very song became the thing that converted jocks into fans, and helped sell the underground to the world.

Cobain tried to use his platform for good. He naïvely hoped to use fandom to change small minds. “I wanted to fool people at first,” Cobain said. “I wanted people to think that we were no different than Guns N’ Roses. Because that way they would listen to the music first, accept us, and then maybe start listening to a few things that we had to say.” That couldn’t work. Hendrix said, “If there is something to be changed in this world, then it can only happen through music.” But fighting homophobia, racism, and misogyny was too complex for a strictly musical approach, though apparently Cobain was pleased that ’90s high school kids briefly fell into two camps: Nirvana kids and Guns N’ Roses kids. Even Cobain got tired of this. In the Incesticide liner notes, Nirvana wrote: “If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us—leave us the fuck alone! Don’t come to our shows and don’t buy our records.” In Utero’s liner notes too: “If you’re a sexist, racist, homophobe or basically an asshole, don’t buy this CD. I don’t care if you like me, I hate you.” It was a beautiful, bold move. Maybe his sense of powerlessness overwhelmed him.

Watching the jocks at my private high school steadily grow out their hair in 1993 made me want to abandon certain “alternative” bands completely, dumping them like the embarrassing pleated slacks my parents made me wear to weddings. Jock guys’ vibe became, Oh, Aaron, you like Alice in Chains, what’s up. And mine stayed the friendly neutral, Hey, what’s up back at you, brother. We had a friendly rapport. We treated each other with respect. It was like a détente across a cultural border fence. But when I first grew my hair out, they called me “scrub.” Scrub was a scruffy dude, a stoner or bohemian, not a clean-cut type in a Reyn Spooner Hawaiian shirt like them. I always thought: If you call people scrubs, you’ll never understand anything. Other towns had their own word for the non-conforming cliques. In Olympia, Washington, where Carrie Brownstein lived, they called these outsiders “batcavers.” “Instead of this big umbrella of alternatives,” she told NPR of life before 1990, “there were rockers and heshers, punks and SHARPS, which was the nonracist skinheads—Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice. There were all these microcategories, but you had to find your own umbrella term for them. That was batcavers at my high school. That was the goth. It was everyone that wasn’t normal.” At my high school they were goths or scrubs. After the jocks started taking cues from the cool MTV bands, they dropped that scrub moniker. I wasn’t gonna tell them that long hair wouldn’t change their small minds—especially since in hindsight, my divisiveness meant that my mind was smaller than it should be—but I did maintain my distance. Selling out wasn’t just for bands that went for the money. That spirit was embodied by people who chose that small-minded mainstream lifestyle.

At least that’s how I remember it. It gets weirdly theoretical in hindsight. Daily life is now material for cultural critics and sociologists. All I’m trying to say is that music and life merged for us back then, and our vision could be myopic.

When my friends and I saw Pearl Jam play in December ’91, they were relative unknowns, so we perceived them as underground. But when Ten came out, skeptics already called them sellouts. As an article in Goldmine wrote:

“Annoying,” wrote Robert Hilburn [about Ten] in the L.A. Times. “Offensive,” added Bob Keyes of the Argus-Leader.

“(They) flail about in search of a groove and a song,” concluded David Browne in Entertainment Weekly.

…And from the offended to the disgusted: “Pearl Jam—a hopeless Seattle Sub Pop wannabe band. Ick,” courtesy of Steve Bojanowski, a Triangle staff writer.

Wannabes? I don’t even know what Triangle is, but that review sounded like my judgy teen-self wrote it.

“Many of the too-cool-for-school Nirvana fans were suspicious of Pearl Jam’s success,” The Seattle Times wrote around the band’s 2017 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction. “Kurt Cobain said he didn’t like Pearl Jam’s music. Cobain and Vedder eventually made up, sort of, though they never were what you’d call friends. Pearl Jam, the Seattle band, just didn’t do things the Seattle way.”

Charles R. Cross, the former editor of The Rocket, and author of Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain, detailed this response in The Seattle Times. “They were criticized by Kurt Cobain and others as careerists, but every band in town wanted success,” Cross said. “For some reason, the populism of Pearl Jam—writing anthematic rock, striving to be a band that gets on the radio—these were things that, in Seattle, were not the way people acted. You were supposed to play a bunch of shows nobody saw, release three or four crappy singles on alternative labels and not be a success, and THEN break through. Pearl Jam didn’t follow those rules.”

In VH1’s Grunge special, someone whose name I didn’t catch says, “There was so much suspicion, and so much heat that came down on Pearl Jam for being fake grunge, and for being the ones who could cash in on Nirvana’s success, who really worked their way up and worked for it.” And in a comical twist of fate, both bands ended up playing the same package tour in the winter of 1991. Knowing how Cobain eventually thought of Pearl Jam, he must have hated how Vedder sometimes dove off the stage during Nirvana’s set.

Cobain was wrong that Pearl Jam were sellouts. But he wasn’t entirely wrong about them being commercial. Pearl Jam’s mainstream success starts with Mother Love Bone’s career ambitions. Smelling money in the college radio consumer, PolyGram Records created a whole new label for Mother Love Bone, titled Stardog records, because to make the band seem underground, they decided to erase their corporate label name so not to lower the band’s cachet. In press material, PolyGram announced that “We loved the band so much that we actually bought the Stardog label to get them.” “In reality,” Goldmine revealed, “the company Created Stardog specifically for the band, to give the EP that important ‘underground’ feel.” Marketing is all about shaping perception. Jane’s Addiction had already signed with the megalithic Warner Brothers when they recorded their debut album on an independent label. That’s something few people know. And with Mother Love Bone, PolyGram thought this illusion would increase sales, but only because it thought it understood youth culture. And when Love Bone’s singer died in 1990, two of his band members used their label support to build Pearl Jam’s new audience from their Love Bone foundation, and used the Love Bone fan club to create anticipation for their debut album. That seems smart to me, especially when you consider this was a one-time opportunity for these young musicians’ to put themselves in business for themselves for life. Remember, bassist Jeff Ament was the only member of Green River with a job and no parental assistance. He wanted to make a living making music, not paying off his student loans while working at a restaurant at age 30. I’m glad he did.

Right after Nirvana left Sub Pop to release Nevermind on Geffen’s subsidiary DGC, Cobain was not only reconciling with the change, he was apologizing for it. “The main thing is that we’re just as happy playing our music now as we were when I was cleaning fireplaces in Aberdeen.” he told Option magazine by the pool at Hollywood’s Beverly Garland Hotel. The band was waiting to mix the rest of Nevermind. “There’s still the same excitement,” Cobain said, “so the level of success we’re on doesn’t really matter to us. It’s a fine thing, a flattering thing, to have major labels wanting you. But it doesn’t really matter. We could be dropped in two years, go back to putting out records ourselves, and it wouldn’t matter. ’Cause this is not what we were looking for. We didn’t want to be staying at the Beverly Garland Hotel.”

Even though Nirvana appreciated how Sub Pop’s hype machine increased their visibility and touring activity, Sub Pop had failed on the business side. Sub Pop had taken a full year to release Nirvana’s first record, Bleach! That experience took the bloom off the rose. “We waited for Sub Pop to get enough money to put [Bleach] out,” Cobain said, “and we ended up paying for the record ourselves—$600. Still, when we go on tour, kids come up to us in flocks, going, ‘Where can we ge the record? We can’t find it.’ That’s the only reason we decided to go with a major; it’s just the assurance of getting our records into small towns like Aberdeen.” It was a wise move, but the changes in perception came with costs.

“I don’t blame the average seventeen-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout. I understand that,” Cobain told Rolling Stone during a period of exhaustion. “And maybe when they grow up a little bit, they’ll realize there’s more things to life than living out your rock ‘n’ roll identity so righteously.”

He was right about that, too. But the thing many of us ’90s kids didn’t realize was how economics were the invisible member of so many bands like Pearl Jam and Nirvana. Perry Farrell and company made a killing by creating a music festival called Lollapalooza. He saw 1991 as a cultural moment and business opportunity, and he had the creative vision and the industry connections to execute his crazy idea. When I was a kid, my dad’s attempts to explain how the world worked often fell on deaf ears. When he tried to prepare me to butt heads with the world’s unchangeable forces, he’d revert to his maxims: That’s the way the world works, and It is what it is. In 1991 and ’92, I clung to my righteous rock identity while being unaware of myself a target demographic shaped by marketing messages. Sure, our Stussy shirts were made in factories, just like bad pop music was, but our new breed of rock didn’t sound manufactured like Warrant. In my young mind, you weren’t sold cool music. You “discovered” it, as free agents. How naïve I was.

As much as I love the bands Sub Pop gave us, Sub Pop became a glaring example of how to project an indie image while running yourself like a corporate entity, of how cool underground people function as the salesmen in suits we were supposed to be rebelling against. Granted, Sub Pop’s founders were selling us cool stuff, and they had great musical taste, but the selling process was the same, and to some people it could negate their zine/indie cassette/Evergreen State College pedigree. Even as I devoured whatever Sub Pop sold me, I was totally unaware of how our musical taste and identities were partially the products of marketing, boardroom meetings, media placements, press conferences, distribution channels, and social engineering. If the world’s meat heads were still playing Van Halen and Motley Crüe, then Pearl Jam must be underground.

If someone had drawn a map of the machinery behind my underground music, I still would have only seen the long-haired dudes and punk women in baby doll dresses shredding on stage. I would’ve heard the story of the mysterious surfer who worked as a security guard and recorded “Alive,” “Once,” and “Footsteps” to music written by strangers he’d never met. We often hear magic, because music is magic. But it took a while to fully understand what Fugazi was trying to tell us: “You’re a target.”

Merchandise, it keeps us in line

Common sense says it’s by design

What could a businessman ever want more

That to have us sucking in his store.

Alternative music was the store. Pearl Jam was the merchandise. I bought it and sold it to other people because it was good, becoming a word-of-mouth gear in the underground music economy. Of course it doesn’t matter if it was underground or not. As Ministry singer Al Jourgensen told MTV: “I think there’s two kinds of music: I think there’s good and there’s bad. And hopefully, I’d like to be affiliated with the good side.” Louis Armstrong said that first: “There is two kinds of music, the good, and the bad. I play the good kind.” And if it sounds good, Armstrong added, it is good.

Pearl Jam is good.

Selling out—It was all so overblown. As people said in the ’90s: Whateva, whateva. But it was hard to just brush it off.

Shaped by fame and concerns about losing control of what they’d created, Pearl Jam created their own rules to take back their music and identities. They had to. Vedder ended up having stalkers, panic attacks, and getting mobbed so hard by fans and paparazzi that he became terrified to leave his house. “Maybe I wasn’t ready for attention to be placed on me,” Vedder said, “you know? Also I think it was the practical things that I wasn’t ready for, or the legal things that I wasn’t ready for. I never knew that someone could put you on the cover of a magazine without asking you, that they could sell magazines and make money and you didn’t have a copyright on your face or something.” Saturation often dilutes great music. “When you hear a song that’s a great song,” said Vedder, “play it a million times you never want to hear it again.” So they put on the breaks. Pearl Jam decided to quit relying on traditional promotional channels like MTV videos and record singles. They started doing things Eddie’s way, which was a very punk way—something too few critics gave him credit for.

As their manager Kelly Curtis told Spin: “When ‘Jeremy’ happened and they played at the MTV Video Music Awards, [Sony Music CEO Tommy] Mottola was at the Sony after-party saying, ‘You have to release “Black.”’ And the band was saying, ‘No. Enough. This is big enough.’”

“‘Black’ was kind of a sore subject,” said their A&R guy Michael Goldstone, “a lot of other people in the company really wanted ‘Black’ as the next single.”

“We turned down inaugurals, TV specials, stadium tours, every kind of merchandise you could think of,” said Curtis. “I got a call from Calvin Klein, wanting Eddie to be in an ad. I learned how to say no really well. *I was proud of the band, proud of their stances. We were starting to use the power for more political, more charitable type things.”

“Ed was trying to break up our formula from early on,” said Gossard, “he immediately realized that getting bigger wasn’t necessarily going to make any of us any happier.”

Not everyone approved of the band’s response to fame. “I’ve heard Eddie Vedder complain about MTV, as if he had been bound and gagged to make a video for ‘Jeremy’ and forced to sign a record contract with a major label,” MTV Alternative Nation veejay Kennedy told Time. “Don’t bite the hand that feeds you, and if you’re not hungry, get the hell out of the kitchen.’”

They were in such a confrontational mode that they even named their second album Five Against One, before changing it to Vs.

There’s only so much any famous band can control. At a certain point, your music and identity become things that the public shapes.

“Everyone was kind of taken aback because Pearl Jam was such a complete success right away,” Urge Overkill singer Eddie Roeser told Time in 1993. “They want to make honest music—it’s not their fault that they’re commercially huge.”

One very satisfying thing about the commodification of underground music was the way so-called alternative music pushed so much commercial hair metal off the air waves and out of our faces.

After Nirvana broke in late-91, it seemed like MTV played one incredible new band after another, but that was partly becauseI was paying closer attention. Magazines were plastered with kids in flannel and “best new band” stories. MTV ran alternative music on various shows such a Dave Kendall’s 120 Minutes. Metal remained a huge money-maker, filling arenas with little effort, but it was no longer the sole ruler of the airwaves.

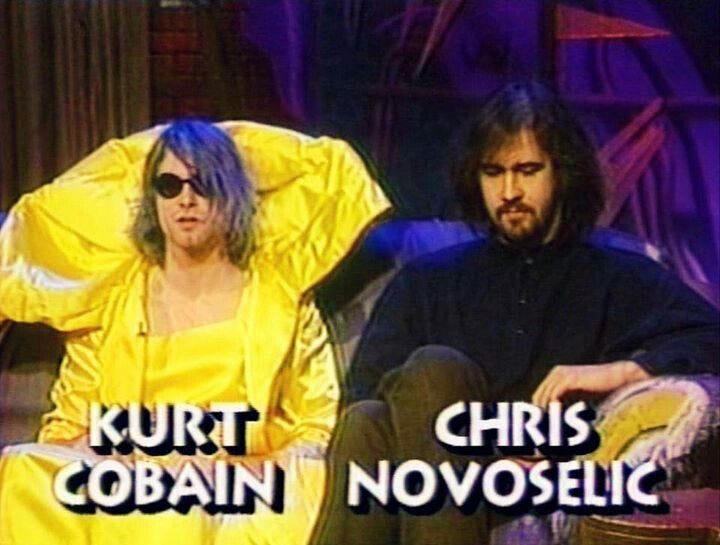

Confused and increasingly outmoded, metal magazines like Rip featured Alice in Chains and Temple of the Dog alongside LA Guns and Mr. Big. MTV’s Headbangers Ball got in on it, famously inviting Nirvana onto the show that made its name from bands like Skid Row. The month after Nevermind came out, Cobain appeared on the show wearing an over-the-top yellow dress with a garishly large collar. “It’s Headbangers Ball,” he told host Riki Rachtman, “so I thought I’d wear a gown.” Look at Rachtman’s hair. How could Cobain not fuck with him? Nirvana were not into headbangers. Noveselic told listeners “There’s more bands out there than just these, like, mainstream, giant, Harley-riding rock bands. That’s kind of one of our missions.” He was being diplomatic in order to reach people and turned them onto a range of music. Asked about what he was listening to, Cobain told Rachtman: “We like all kinds of stuff: Leadbelly, Bikini Kill, The Breeders, The Pixies, R.E.M., The Melvins.” Rachtman said, “I’ve heard of three of those bands.” And he told them that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” had ranked as Headbangers Ball’s “Number Five Skull Crusher.” The band was nonplussed.

Nirvana was in good company. When Rachtman interviewed Glen Danzig in 1992, Danzig took to subtly diss the longhaired sellout host, and he mentioned his love of the Velvet Underground and Bauhaus and cut into the mainstream press’ lack of vision: “There was a time those bands were around and …[the press] should have asked questions about those bands at that time. And they didn’t ask the questions then. Now they want to ask the questions. Well, you blew it.” And when Rachtman interviewed Ministry in 1992, it was because their album Psalm 69 earned them some metal fans, even though Uncle Al always dismissed fame and genre as things people construct after-the-fact.

Speaking of Al: Not everyone thought selling out was bad.

“Usually you have, like, artists going ten years,” a young, more handsome Al told MTV, “beatin’ their head against the wall writing great music, and they just get tired of being poor and they sell out, make lots of money, get on a major label—blah. You know the story a million times over, right? With us, we sold out from when we started, which is, you know, kind of interesting.”

Musicians have financial demands, too, few more than parents or drug addicts. They can’t live these pure artistic lives for listeners’ sake. Instead of working at Tower Records and B Dalton Books to pay for rent and food, why couldn’t ’90s musicians make music their job so they could also enjoy how they spent their working hours? That’s not a philosophical betrayal. That’s living your best life. Ministry’s Uncle Al knew that. That said, he also brazenly held loaded syringes during interviews and talked about his wild intoxicated antics like it was enviable. Of course he was happy to sell his music. Drug habits require money. He stayed so loaded during the ’90s that he claims not to remember much about writing Ministry’s incredible albums Psalm 69 and A Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste, which stand the test of time. Al looks like shit now. And you know who looks physically fit? Pearl Jam. The professionals have aged well. Vedder is worth approximately $120 million dollars, and time has proven his band to be the artists that many denied they were.

Remember, Pearl Jam wrote 11 new songs during their first week practicing in Seattle together. It might be a myth, but I remember reading that Vedder spontaneously composed the lyrics to “Release” as he sang them in a demo session. And Vedder famously scribbled the lyrics to “Ocean” on a scrap of paper in the rain. He got locked out of the studio after he went to put change in the parking meter. He wasn’t dressed for the rain, but no one could hear him pounding on the studio door. He thought, Fuck it, I might as well write something. So he scribbled lyrics to Ament’s bass, which was all he could hear through the boarded up window. Their first songs didn’t all come out at once, like “Deep.” “I was walking in Seattle,” Vedder told the audience at a 2012 Manchester show, “I’d only lived there less than a year, and a lighter fell out of the sky onto the sidewalk. I looked up to see where it was coming from and about four storeys up there was a guy—real skinny, kind of scabby looking dude—in a windowsill with a band around his arm, putting a needle into the inside of his elbow. Once I saw that, I just knew I would never fucking do that. It was the most pathetic thing I’d ever seen.”

In 2021, I watched footage of Pearl Jam playing “Breath” in Seattle in 1991, right before Ten came out. There’s no doubt: This is a real band. Sorry Kurt, as brilliant as you were, their music came from the same powerful, mysterious place that yours did. You can feel it. And knowing how they wrote their first songs only confirms it. Popularity isn’t an indication of their early music’s potency any more than popularity is proof that something sucks. You can tell from their stage presence those guys were into this.

“The biggest thing that really stuck out in our minds was we [Mudhoney] had a horrible time on the Nirvana tour,” Mudhoney guitarist Steve Turner told Spin. “Cause it was just really unorganized and everybody was unhappy, crew members were being fired left and right, they were trying to tell us that we couldn't have beer backstage because they were trying to make it a dry tour. So then we were like, fuck, if that’s what the Nirvana tour was like, what the hell’s the Pearl Jam tour gonna be like? But we did it, and immediately it was such a better atmosphere. We were absolutely bummed for Nirvana, but God, they’re having such a horrible time, everything sucks, ya know. And it shouldn’t. Just watching Pearl Jam. The crew was really happy and really nice people, a lot of them are still with them today, since day one. It was just really pleasant, really fun. There were some skateboards, I remember skateboarding around with Jeff backstage. It really did change my perceptions of the whole thing. It just seemed like they’d actually worked for it and so they weren’t going to pretend like they didn't want it. And they also weren’t going to act like big stupid rock stars.”

Like Nirvana trading Sub Pop for a major, Pearl Jam were talented and driven and wanted a music career. They deserved their success. They’re incredible songwriters, tireless performers, and they care about their music and fans. Early skeptics questioned the band’s authenticity, but Pearl Jam kept evolving. They tried new sounds and didn’t lock themselves into one style. Only in my late 30s did I discover the power of their mid- to late-90s albums No Code and Yield, and even the later one fans call the avocado album, all of which I ignored when they came out. When I listen lately, I don’t listen to Ten. I listen to Vitalogy, Live on Two Legs, and their live pirate radio broadcasts, which contain firey versions of “Do the Evolution,” “Brain of J,” “Red Mosquito,” “Hail, Hail,” “Indifference,” “Off He Goes,” “and “Satan’s Bed.” However you cut it, that’s good rock ‘n’ roll. Even when Stone Gossard quit trying to look cool, choosing to wear gym shorts and jogging shoes on festival stages, those late-90s songs are way better than anything on Ten. After 30 years, Pearl Jam still gets listeners through good times and bad, and that’s something that transcends the old ’90s value system. The band has also used their wealth and visibility for countless social and environmental causes. They don’t have to do that, but they did. Cobain would’ve appreciated that. It’s safe to assume that young Cobain would have disliked hearing Iggy Pop’s music on car commercials, but had he lived, Cobain and Pearl Jam might have seen eye-to-eye in middle age.

It isn’t widely known, but Cobain and Vedder did have a truce.

“I remember that at the MTV Awards in ’92, Eddie and Kurt kind of made up,” said MTV/VH1 producer Rick Krim. “I almost remember them underneath the stage, grabbing each other. Clapton was playing ‘Tears in Heaven,’ I think, and they embraced under the stage. Kind of a magic moment.”

“Yeah, some kind of fucking summit,” said Grohl, “it had blown so out of proportion. I remember the two of them smiling and hugging each other—[sarcastically] and then, all of a sudden, Seattle was okay!”

“That’s all been taken care of now,” Vedder told Melody Maker, “that whole relationship.”

Then Cobain died.

“I remember tearing up my hotel room in a complete rage when I found out,” Vedder told Spin. “We played that night [near Washington, D.C.], and I still question that. [Fugazi’s] Ian MacKaye was there, and he offered to take me in that night. So I went to get my suitcase from the hotel, but I didn’t have a key, so I had to go up with the maintenance guy to let me in the room. When he opened the door, I just looked at him and said, ‘You have to understand what happened today.’”

And Cobain probably would’ve stayed connected enough with youth culture to have learned from Millennials and Gen Z.

“After its ’90s peak,” Slate writes, “the stigma of ‘selling out’ went into remission. The commercial licensing of all 18 tracks on Moby’s 1999 album Play is often cited as the tipping point, as the collapse of the music industry sent artists looking for new licensing revenue and corporate touring partnerships.”

Millennials and Gen Z don’t think in these terms. For them, there is no selling out. There’s not enough physical media to sell to make a living. Without album sales to generate revenue, touring and corporate sponsors are two of the few reliable ways for musicians to make money. Sell a song to a commercial and go congratulation yourself. Success isn’t staying independent. It’s licensing music to brands to keep making music. In fact, many artists already work for big brands as designers, copywriters, and photographers. They call themselves ‘creatives,’ not sell outs. As James Wolcott wrote in Vanity Fair in 2007, “Today, ‘selling out’ is so commonplace it doesn’t even seem like a syndrome.”

Hip-hop wasn’t selling out by selling their music. They were making a living and a place for themselves in white America that systematically oppressed and robbed them of opportunity. With hip-hop money, artists build more than musical careers. They build businesses, corporations, empires, selling everything from production services to clothing to cologne. Some build enough power to leverage meetings with the United States Presidents. Now that’s smart. Why let an ideal keep you down when racist America does that for you? You can be both an artist and entrepreneur. Rap artists and younger generations have a lot to teach us ’90s kids.

If music offered evidence of how cool my friends were, music’s cachet also worked against me by amplifying the subtle arrogance and negativity that already poisoned my mind. During the early ’90s, I hated your bands. We had taste. We needed proof that you did, too. Back then my teenage heart was filled with hate. I didn’t express it by insulting or teasing anyone. I cuddled my pet gerbils and made homemade holiday carts for my grandparents, but my anger came through music. The 45-year-old me apologizes if your favorite song was on my hate list, but back in the day, I defined myself in opposition to so many of the alternative era one-hit-wonders that played everywhere we went. I hated: Blind Melon’s “No Rain.” I hated Tonic’s “If You Could Only See.” I hated Jesus Jones’ “Right Here, Right Now,” hated Eagle-Eye Cherry’s “Save Tonight,” Seven Mary Three’s “Cumbersome,” Toadies’ “Possum Kingdom,” Dishwalla’s “Counting Blue Cars,” Collective Soul’s “December,” Soul Asylum’s “Runaway Train,” Lit’s “Miserable.” Barenaked Ladies’ “One Week.” I hated that Australian Nirvana copycat named Silverchair and anything by 311, Live, STP, Jimmy Eat World, Cherry Poppin’ Daddies, and Smash Mouth. I didn’t know many of these bands’ names, only the songs, and they were horrible. I’m sorry for being such an opinionated little prick. I’m sorry if I hurt peoples’ feelings by making them feel small. I’m all about love now, and I don’t care what music anyone likes, as long as it moves their spirit and their booty in some way. But I had internalized this teenage value system, and I had to free myself of it. Inevitably, I turned on Pearl Jam.

By 1994, I’d distanced myself. Ten was great initially but it was old music now, of a time, and I’d moved on. I treated the band like kindergarteners treat potty training: as an embarrassing artifact from early times. I was in college now. I didn’t listen to that stuff. I’d grown into my big boy rock and jazz pants, thank you. It got lonely on Too Cool Island.

I’m glad I eventually came back to Pearl Jam.

Whatever Pearl Jam was to people in the ’90s, however invisible they may be to Gen Z, in 2021, the band remains an active one. You have to respect that.

“American rock bands, they break up,” Chris Cornell said at Ten’s twentieth anniversary. “Pearl Jam managed to stay together.”

On March 27, 2020, Pearl Jam released their eleventh studio album, Gigaton, seven years after their last one. “Pearl Jam unhip?” an LA Times headline read. “Yes, but new album…” It was a dick headline, but PJ didn’t need the Times’ love. They had their fans. Once Pearl Jam started playing big venues, they never stopped filling them. Somehow, unlike other bands whose star lowers and fanbase shrinks, PJ never lost fans or went back to playing small clubs. As one fan wrote at Consequence of Sound, die-hard Pearl Jam fans are unique because, “At the risk of sounding creepy, I might draw the distinction that I don’t love this band — I’m in love with this band. Following them feels more like being in a relationship than merely being a fan of a rock band.” They have few contemporaries. Mudhoney still tours. The Melvins still tour. Mark Lanagan still tours. L7 reunited in 2015 to tour. Soundgarden dissolved after Cornell took his life. And Nirvana ended with Cobain in 1994. Pearl Jam outlasted them all.

In July 2020, COVID-19 forced Pearl Jam to reschedule their European tour for June and July of 2021. That date proved optimistic, as the pandemic raged on. So they rescheduled for 2022, putting four years between that tour and their last live show. They have time. If fans can wait, the band can.

“American rock bands, they break up,” Chris Cornell around the twentieth anniversary of Ten. “Pearl Jam managed to stay together.”

As one fan said in their documentary, Pearl Jam Twenty: “I didn’t realize how much they’d given to us as a band, and how much we appreciate that.”

As someone who’d quit paying attention, their sustained creativity is incredible. They’re one of the greatest rock bands in history. As a YouTube commenter said about a video of Eddie Vedder at home:

kurt: dead

layne: dead

chris: dead

scott: dead

eddie: “Ohh, I’m still alive”

Another commenter chimed in: “The last living grunge man. We must protect him at all costs.” A thousand likes agreed.

But they neglected to mention Mark Arm from Mudhoney. It’s okay. He works doing shipping fulfillment in the Sub Pop warehouse, and he doesn’t need recognition. He predates all those motherfuckers. And he and Pearl Jam get along.

You might find it interesting that Paul Skallas plagiarized this article for publication at his newsletter: https://www.getrevue.co/profile/Lindy_Newsletter/issues/weekend-reads-1402275

This was a fun read for me; I graduated high school in 92. Part of me is proud that the bands I "discovered" never made it big (e.g. Swervedriver, Ride, Adorable), yet at the same time, in hindsight, it's sad.