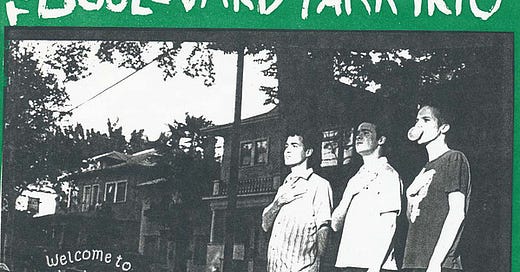

The Boulevard Park Trio: One and Done

This obscure Sacramento band's only record embodies the timeless beauty of bored, talented youth entertaining themselves in a hot, flat city in the 1990s.

“In some ways I like that every day is just one long day here.” —Scott Miller

The song “Another Crush” by Sacramento’s The Boulevard Park Trio evokes such distinct, cinematic feelings in me that it’s hard to believe I have no personal connection to it beyond the music. I’ve never lived in Sacramento. I didn’t listen to this band during my impressionable …