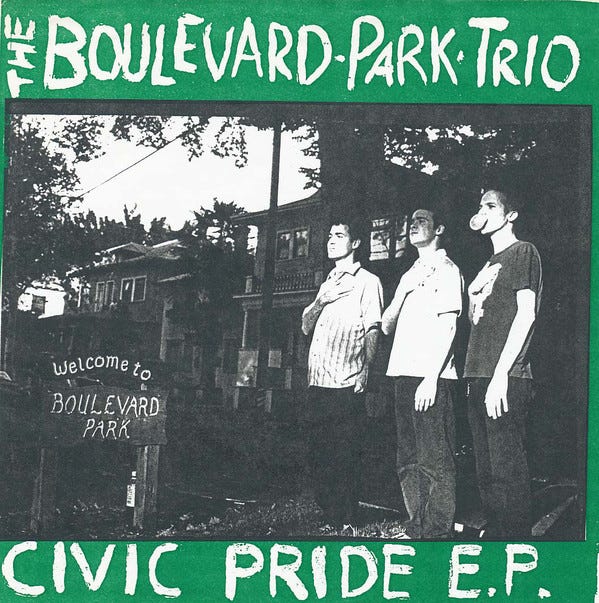

The Boulevard Park Trio: Part Two

The longest music story in the world continues whether you want it to or not.

(CONTINUED FROM PART 1)

The Yah Mos got booked to headline a three-day punk festival in Shasta, California in 1995 or ’96. They were flattered but also bummed: Three days of punk? During three days of any one musical style, every band starts to blend together. How do you close three days of punk? The Yah Mos decided to open their set with a straight up r…