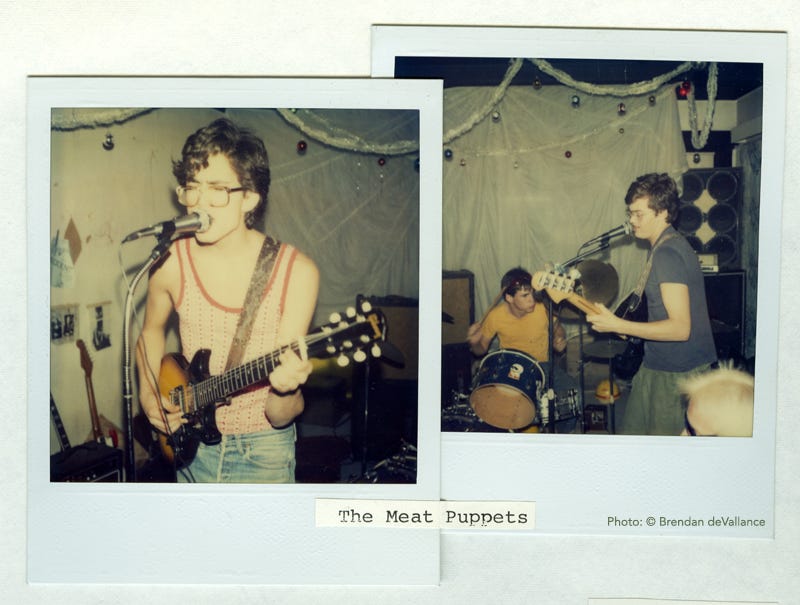

The Meat Puppets

Seeing the Kirkwood brothers perform together for the first time in eleven years was a powerful experience for a longtime fan like me. They are a band that transcends time.

Midway through their March 14, 2007 SXSW gig, Meat Puppets bassist Cris Kirkwood told the crowd, “This just happens to be the first time in 11 years that Curt and I are gonna play together, so.” A roar reminiscent of a NASCAR rally echoed through the small, outdoor club, and Cris raised his arms, both visibly dotted with the white scars of old burns and needle marks, in what seemed part gratitude, part inauguration. “It’s pretty coooool,” he chuckled.

Half bluegrass, half electric, the 30-minute set was part of a string of warm-ups leading to the July 17, 2007 release of Rise To Your Knees, the first album Cris and his guitarist brother Curt recorded together since Cris’ spiral put the legendary band on hiatus. Hiatus, Curt insisted. Cris was never kicked out, and Curt never retired the band. “I don’t have to check my interest in this shit,” Curt told me from his Austin, Texas home the week before the show. “It doesn’t seem old to me in any way.”

I felt the same about his music. Few bands have managed to move me as consistently through the decades as the Meat Puppets. Their early music sounded as fresh as their new stuff, and they just kept making more.

That’s why I went nuts when a post appeared on the Meat Puppets’ Myspace page in April 2006, written by what seemed to be Curt Kirkwood: “Question for all! Would the original line up of the Meat Puppets interest anyone?” Turns out his daughter wrote that. She was his “internet assistant.” He used Myspace for publicity but despised it. “I don’t have any need for networking. I am a network,” he told me. “I understand how much I’m missing not being Paris Hilton and not living in California, and I’m going to commit suicide if you don’t read this.”

The Kirkwood’s reunion was a huge deal. That’s why I’d flown to Texas just to see this show and the all electric one at The Parish the following day.

Formed in 1980 in Phoenix, Arizona, the Meat Puppets built their reputation on a carefree embrace of experimentation and evolution. Self-satisfying creativity was job one. Before Uncle Tupelo ever provided the name No Depression to the now defunct music magazine and the this-isn’t-your-pappy’s-country-music sensibility, the Puppets were mixing country, thrash, and Americana with hard-charging rock and Jerry Garcia-ish psychedelia. They played over-amplified versions of “Dixie Fried” and “Blue Bayou” in Phoenix punk clubs in ’81, and they covered everyone from Kris Kristofferson to George Jones at a time when singing to Hank Williams was still something to hide from many of your friends. In one show they plunged into The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” after Patsy Kline’s “I Fall to Pieces.” Along with the Brothers’ verging-on-off-key harmonies and Curt’s nimble guitar work, the Puppets’ one constant has always been change. Up On the Sun is a jazzy, jam-based trip into acid daylight that consistently ranks as a fan favorite. Huevos is guitar-driven, ZZ-top rock that many fans complain sounds too thin and commercial. Too High To Die is the band’s catchy, moody, fuzz-heavy commercial cross-over loaded with infectiously memorable hooks. That’s range. “I don’t care if any of my fans want to hear anything,” Curt said of their music. “That’s not how this works. They have a good time at all the shows. The other side is completely self-indulgent stuff.” That fierce independence—making art for yourself, not your audience—certainly moved musicians like Kurt Cobain to proclaim: “The Meat Puppets gave me a completely different attitude toward music. I owe them so much.”

Cobain reciprocated by inviting the Kirkwood brothers onstage to record “Oh, Me,” “Plateau,” and “Lake of Fire” on Nirvana’s Unplugged, not only lining their pockets with impressive royalties, but introducing the band to incalculable listeners. Too High went gold, produced the band’s only charting single, “Backwater,” and the band played sold out stadiums on Nirvana’s U.S. In Utero tour. Despite the increased recognition, in 1994, the Puppets’ 14 coherent years began to unravel.

Following Too High’s release, they toured with then-Alterna-darlings Cracker and Soul Asylum, and during that summer’s Stone Temple Pilots tour, Cris developed a cocaine habit. Hit-makers STP were already multimillionaires, and as Curt recalled in a 1998 Phoenix New Times article, ounce bags of coke and boxes of straws fueled that tour. Singer Scott Weiland struggled with addiction for years after, doing jail time, ruining his marriage. He eventually died of an overdose at age 48. Cris fared only slightly better. Period concert recordings capture a band full of energy: forceful harmonies, tight renditions, and what sounds like fun. But listen closely to the intro of the 1994 Fillmore show, and you’ll hear Cris greet the crowd with, “I am so fucked up.” He stayed fucked until 2004.

While age was busy graying Curt’s thick hair and carving lines into his cheeks, technology was busy changing the music business. YouTube became the new MTV, social media the new marketing platform, and file-sharing threw record labels’ roles into question. Like Miles Davis said, “If you aren’t appearing, you’re disappearing.” Curt never disappeared. True to his musical vision, he reformed the Puppets with new members for 2000’s Golden Lies, played a 2001 solo tour, formed the short-lived Eyes Adrift with Nirvana’s Krist Novoselic and Sublime’s Bud Gaugh, Gaugh formed another one-off side project called Vocano with members of Long Beach’s music community, and released his first solo effort, Snow, in 2005. Eyes Adrift’s only album contains some of Curt’s catchiest songs. “It’s not really a comeback,” said Curt. “It’s more like, Cris was really sick.”

It’s true. When I showed up at Portland, Oregon’s Aladdin Theater in 2001, Curt was generous enough to let me film his solo performance that night. He was as inspired and brilliant as he had always been.

But by the time Cris last abandoned rehab, Curt had distanced himself and moved from Phoenix to Austin. “I always had good friends here, like Paul [Leary] and Gibby [Haynes] and Stuart Sullivan.” Leary, who co-produced Too High To Die and its follow-up No Joke!, might have produced Rise had Curt thought to ask. “That would’ve been cool,” Curt told me in his stoney, laconic. “I don’t know if he woulda’ charged me any money or not. I don’t have any money.”

Being on the indie Anodyne Records, the Puppets approached Rise as they did classic SST albums like Up On the Sun: really fast, really cheap. “It’s like the old days,” Curt said, “like punk rock: You didn’t see them chargin’ any less for their records did ya? They didn’t fuckin’ cost anything, but they sure charged the same as someone who put a couple hundred grand into it.” Curt would know. No Joke! cost London Records over 200,000 dollars. Rise only cost a few thousand. “We took five days to record it,” Curt said, “and a couple days to mix it.” As an exercise in fiscal restraint and artistic independence, they tracked mainly at Austin’s Wire Recording, operated by Curt’s engineer buddy, Stuart Sullivan. Curt was pleased. “It’s song-for-song one of my more successful things.”

“With Meat Puppets in the ’80s it was a lot of, ‘Well, that’s cool,’” Curt recalled. Later, amped on coffee or playing to the record, he often found renditions too slow and wondered, “‘Why didn’t I think to record that to my liking now?’” Meaning, moodier or faster. Thinking songs should’ve been played faster is Curt’s Achilles heel. But a high thrash-capacity sparked the band’s recording career.

When L.A. punk band Monitor couldn’t play their song ‘Hair’ fast enough, they asked the Puppets to record it. Monitor provided studio time and, like good friends do, eventually released the session’s five Puppets originals on their own label, re-released later as In A Car. Rolling Stone writer Michael Azerrad called the Puppets “one of an elite group of pioneering bands that …[blazed] an underground railroad of indie-oriented clubs, stores, radio stations and fanzines.” Radio and records were never Curt’s deal. “I was more of a band guy. I just liked to have a band, liked to play a lot of music.” Curt dropped out of college to play. After he, Cris, and original Meat Puppets drummer Derrick Bostrom teamed up, Derrick’s punk rock merged with Cris’ art rock-fusion jazz and Curt’s straight Zeppelin rock. Derrick also upped the Kirkwoods’ anemic indie-business sense. “We’re from Phoenix,” Curt told me. “We weren’t thinking, ‘We’ll get a video and blah blah blah,’ or, ‘Oh, we’re gonna make a record.’” As a native Phoenician, I knew what he meant. He described playing Average White Band and The Blackbyrds in a bar band where everyone wore powder blue, three-piece suits. “I think Derrick knew a little bit more about the actual ‘bands that are cool make records.’” During breaks between tours, the Puppets recorded seven records for SST. Label-mates may have included punk bands like Black Flag, and the Puppets’ twelve-song debut may have totaled, in typical punk fashion, twenty minutes, but the curveball inclusion of “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” and Doc Watson’s “Walking Boss” foretold the genre-bending, countrified vastness of their entire career. It wasn’t a curve for the band. They always played that stuff live, and Jerry Garcia was a huge influence on Curt.

Fans consider Too High a classic, and London predicted big sales for No Joke!, but with Cris nodding in the sessions, record execs eventually pulled promotion. Between No Joke!’s October, ’95 release and the Puppets’ final tour with Primus, Cris and his new wife Michelle retreated to their Tempe, Arizona house, smoking coke and shooting dope delivered by dealers like Chinese food. Cris’ two No Joke! songs boast of newfound escapism, as in “Inflatable” where he sings, “Gotta run gotta hide / Gotta get away / Gotta run gotta get away.”

While the tips of Cris’ fingers turned scaly black from pressing rock onto Brillo, Derrick bowed out of music entirely to work at a Phoenix Whole Foods, and Michelle fatally overdosed. Cris’ woes wouldn’t end there. In 2004, he received a twenty-one-month prison sentence for assaulting a security officer in a Phoenix post office; during the bizarre incident he also got shot in the abdomen. Curt, unwilling to retire, moved on without them.

“Just my experience as a professional musician,” he told me. “You pretty much have to stay on it unless you’re stupid successful.” He characterized No Joke! as “kind of a lost record in a way,” though he wouldn’t describe it, or success, as stolen. “You’re balancing on top of people who are just completely insincere and all this shit, your own insincerity. It’s not that great a place to be anyway.”

In a sense, the Meat Puppets peaked commercially in the mid-90s, playing to their largest crowds while opening for Nirvana, and grossing their biggest bucks. But maybe it’s the other way around: The 90s peaked with the Meat Puppets’ Too High To Die. They remain one zenith of musical creativity, and one that couldn’t be contained in any genre any more than they could maintain mainstream popularity. The 90s were all about turning underground bands into mainstream money-makers. To me, the 90s peaked in the scorching version of “Oh, Me” that the Puppets played at The Roxy in Los Angeles in 1994, which is one of the best of the countless versions I’ve heard them play.

It was unfortunate but not tragic that their career temporarily ended in 1995, because their creativity had been going strong for the previous 15 years. Few ’90s bands could boast such a flawless pile of albums. To their art, a decade was an irrelevant measure of time, because their consciousness expanded infinitely in all directions, essentially dissolving notions of time and progress and success entirely, making their music timeless. It was just a shame the band couldn’t keep capitalizing on that. After finally earning the kind of money their talent deserves, the money dried up.

As the Kirkwood brother’s 2007 reunion proved it was still fresh, relevant music.

Even though their punk phase was short-lived, the Puppets came up as a punk band in Phoenix.

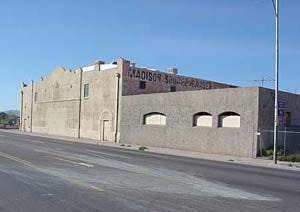

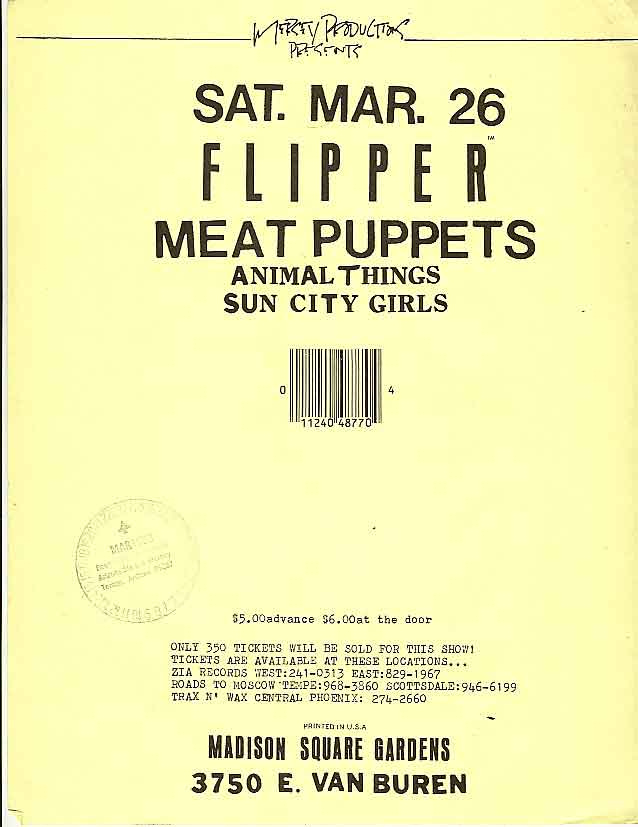

Anyone who thinks the original incarnation of punk rock passed entirely over Phoenix just weren’t there. I wasn’t there either—I was in elementary school nearby—but apparently 1979-1984 were the golden years, and at the center of it all sat Mad Garden. Short for Madison Square Garden, this seminal punk club took its name not only from the New York landmark, but from a cavernous, 1929, brick wrestling and boxing arena on 7th Ave and Van Buren Street. When Tony Victor, owner of Placebo Records, the Valley’s sole, period punk label, started booking shows in ’81, he booked them at another old wrestling dive. It stood on 37th Street and Van Buren, across from Bill Johnson’s Big Apple, and it too was called Mad Garden.

Bands played in the wrestling ring at the building’s center, setting their amps and drums on the padded floor between rubberized ropes. The stage wobbled during performances, adding visible bounce to the already agro musicians’ antics. Scratched wooden bleachers lined walls decorated with black and white publicity photos of small-time, largely deceased wrestlers in period regalia. A chain link fence enclosed the stage in order to protect fans from flying wrestlers; a previous owner installed it after a wrestler landed on someone in the front row. Instead of protection, the fence provided the perfect monkey-bars for punks to climb during shows.

While London and NYC already boasted legendary punk scenes by 1975, Phoenix’s started in ’78 with the birth of The Consumers and largely ended with Mad Garden’s closing in ’84. In the interim, local bands like JFA, The Feederz and Mighty Sphincter left a lasting impression on their generation, with Mad Garden serving as the center of the action. For big-name touring acts, the rowdy ring provided a reliable playground. Everyone played there: Bad Brains, Black Flag, Violent Femmes, The Minutemen, Butthole Surfers, Minor Threat, Bad Religion, Husker Dü, and, of course, locals like Meat Puppets, Victory Acres, and Sun City Girls. As JFA’s singer Brian Brannon sang in a song penned specifically for the club’s closing night, Mad Garden was “A hall where weirdoes sometimes wrestle/A fitting place for us freaks to nestle.” The word ‘freaks’ was key. That early crowd wasn’t punk in the formulaic fashion sense—liberty spikes, combat boots, Clash patches on jean jackets—it was equal parts skater, student and New Wave.

Victor made a natural booking agent. His uncle leased the 37th Street building for wrestling events, and being a music fan with a bassist for a business partner, Victor knew all the angles: keep covers cheap and Mad Garden BYOB so minors could attend; blanket the city with hand-drawn fliers; use your uncle’s karate school employees as security; then sell beer inside where cops couldn’t see. The result was a grubby, grassroots, communal atmosphere that one clubber described as “the rowdy punk rock equivalent of the company family picnic.” Like any killer picnic, though, the ants eventually arrived to carry off the food.

Police surveillance, obstinate neighbors, and a raucous parking lot party squad sealed The Garden’s fate. Fire regulations kept crowds under 350, but a few gigs, like two back-to-back Dead Kennedys shows, drew over 500 people, along with the Fire Marshall. Despite fliers bearing desperate warnings (“Please! Help keep the Garden from closing down! Don’t show up until you’re actually ready to go inside!! Okay?”) The Garden closed in January, 1984, after a beer-soaked, full-house, adrenalized goodbye gig featuring JFA, TSOL, and Crucifucks.

Then the building became a Spanish bible study center. Or was it a plastic flower warehouse? It depends who you ask.

The Puppets quickly outgrew all of that. Punk was too restrictive. “It’s kind of like, we were into pot and LSD,” Cris Kirkwood told one interviewer, “and it wasn’t really around in the punk rock scene when we first came around. People were maybe more into crank or something. I don’t know.” Besides the acid and weed, the band dreamed music that had as many colors as their own musical tastes, which included pop, country, dinosaur rock, and ABBA. “Parts of [Meat Puppets I] are exceedingly fast and screeching shit—but it ain’t straightforward punk rock at all, it’s our own version of it. Then we also did Sons of the Pioneers’ “Tumbling Tumbleweed” on that and “Walking Boss” from Doc Watson. We were willing to go to different places and we showed a side of ourselves that took everybody by surprise, but it was also profession. There’s the influence from the Dead in doing what the fuck we want to do. We were always kind of the outcast hippies of the punk rock scene anyways, you know.”

The Puppets were not only outsiders to the punk world. They challenged narrow punk thinking by playing decidedly non-punk covers, which antagonized audiences. Punks thought yelling their songs while wearing a dog collar was rebellious. Try playing the Grateful Dead’s “Scarlett Begonias” to an early 80s punk crowd. The Puppets went beyond covering Hank Williams and Little Richard. At one 1982 show, they covered songs by Neil Young, Fleetwood Mac, ZZ Top, Led Zeppelin, CCR, The Feederz, Grateful Dead, The Olympics, and Vox Pop. That was over half of their set! “Hello,” Curt said when they came on stage, “we’re the meat puppets and we suck.” Drummer Derrick Bostrom challenged punk audiences further by wearing tie-dye and a headband.

Fortunately, before they left the punk world, the band recorded numerous early shows of theirs through small clubs’ soundboards, including a blazing 3/23/83 show at Mad Garden. I found it two decades after it was recorded. It’s timeless.

Having grown up in Phoenix, the Meat Puppets were always around me, before I even noticed they were there. They grew up there. They still lived there. The Arizona desert appeared on the back of their iconic second album, II. They played shows at clubs my family drove past before I was old enough to recognize them as clubs. The Puppets played a show at the Big Surf waterpark down the street from my house, where friends and I went all the time. One of the Kirkwood brothers even went to my high school. The legend is that he got kicked out after he rode his motorcycle through hall and stairwells of the main building. The Puppets were one of the few Phoenix bands that got popular and that locals could proudly say were from here. As I got older and into music, they became the fluoride in the water, fortifying my musical tastes against the way commercial music could destroy it.

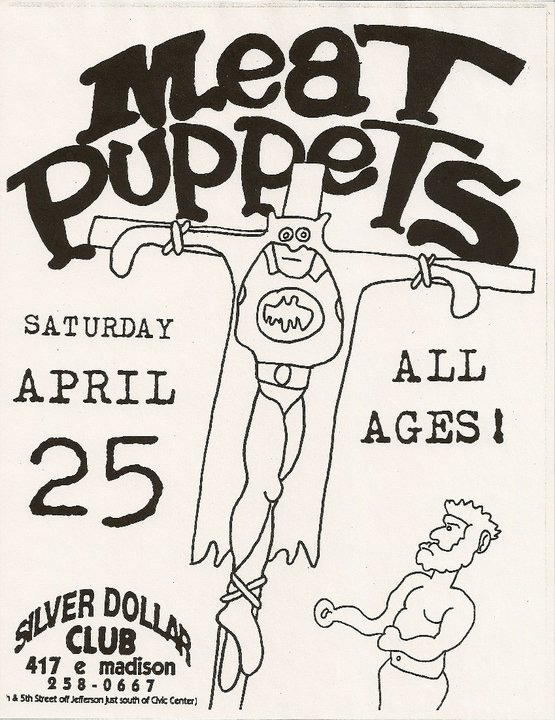

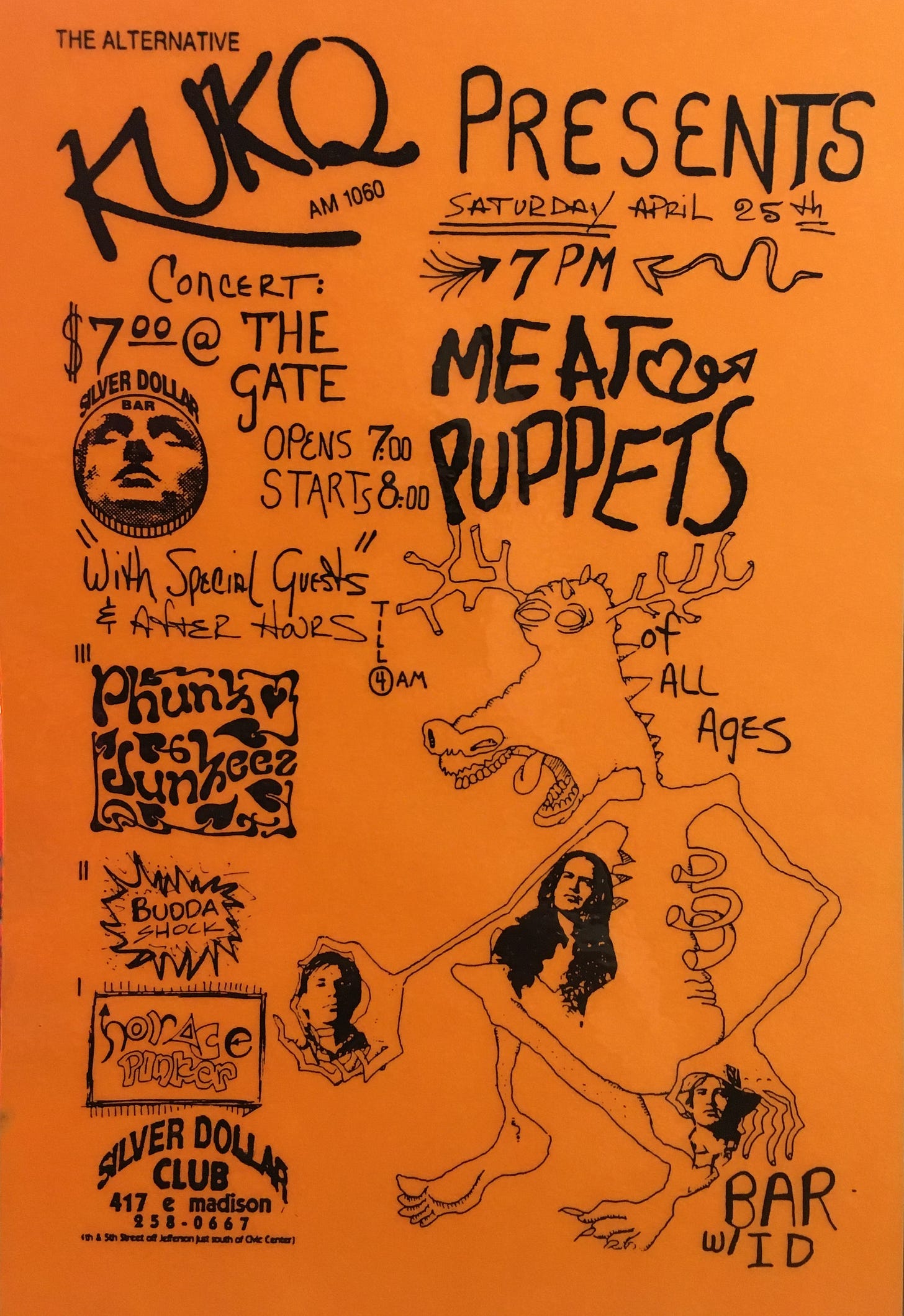

Before I became a fan, I loved their flyers. I loved their weird artwork, the line drawings of monsters with misshapen heads and impossible numbers of eyes, something I understand as acid-induced before I’d ever taken acid, so I collected them.

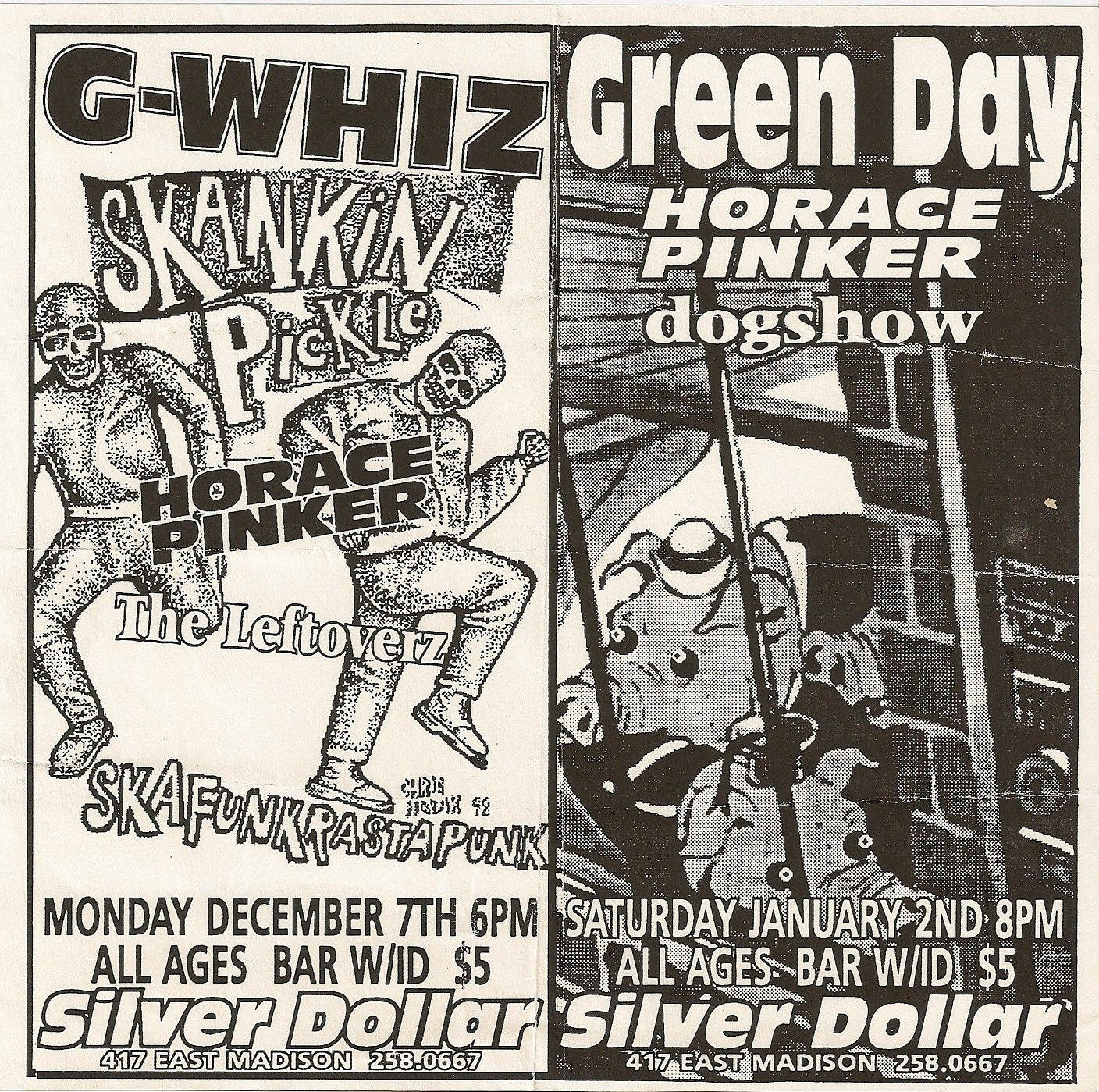

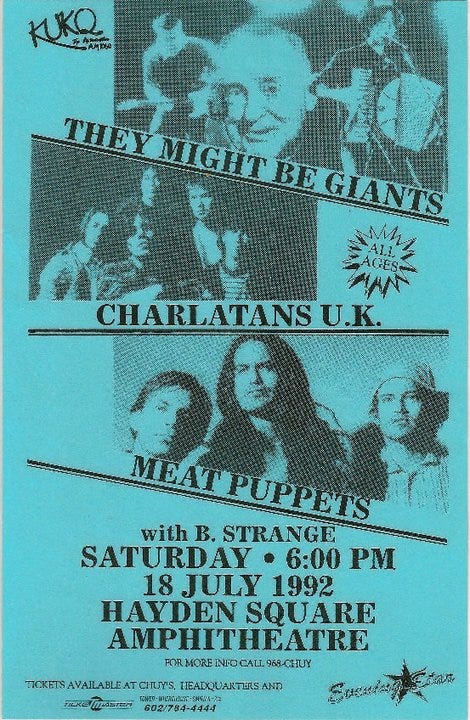

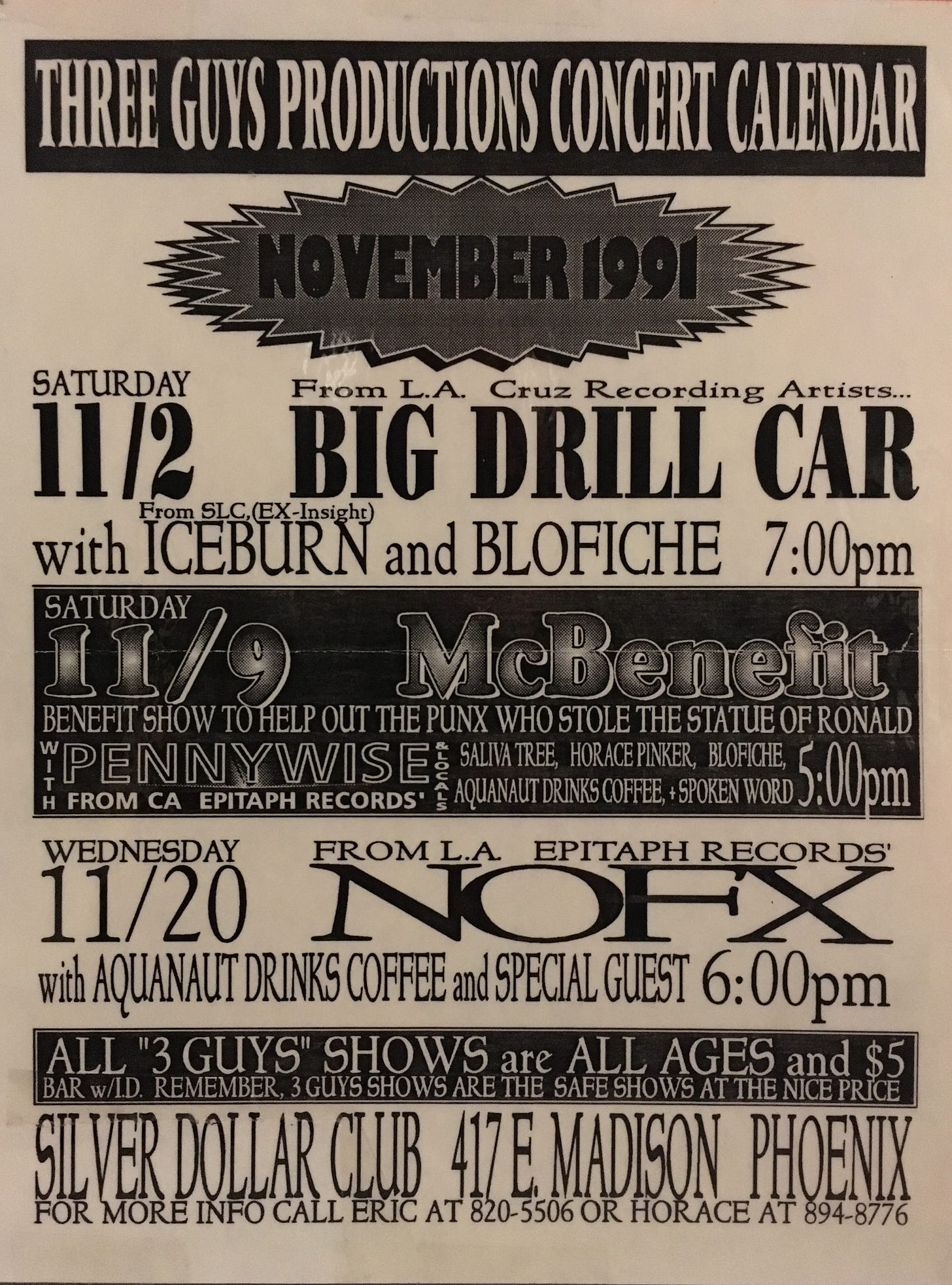

Before my friends and I got our driver’s licenses, we had a weekend routine. We rode our bikes from our houses in south Scottsdale to Tempe. The area around Arizona State University was five miles from our houses. It had multiple record stores, a resale shop, a Mexican-style grilled chicken restaurant, a video game arcade, and most of all, opportunity for autonomy. We’d bike down through a series of interconnected parks, go eat greasy bacon burgers at Carl’s Jr, then buy imports of Depeche Mode, The Wonder Stuff, Red Hot Chili Peppers at Zia and Eastside records. Because we’d started going to shows, we paused to check the concert flyers. Most stores stacked flyers by the front door. Most belong to local bands with awful heavy metal names, but I grabbed ones by underground bands I knew, even when I couldn’t attend the shows. The graphics were cool. Like these:

After discovering Meat Puppets flyers, I started checking for Puppets flyers specifically. I drew all the time, so I appreciated others’ drawings, especially strange ones. By my high school freshman year, the band had been playing for nine years. None of my friends listened to them yet, but we somehow came to understand that the Meat Puppets were a special band with clout. I didn’t understand until my junior year that the Puppets toured constantly and internationally and had influenced other cool international bands like Sonic Youth and Minutemen. My teenage worldview was too narrow for that. Since they were from Phoenix, they were just a Phoenix band to me. Their name was THE MEAT PUPPETS, after all, which amused my adolescent sensibilities and phonetic obsession with words like ‘meat.’ Their hometown flyers listed shows at small clubs like the Silver Dollar Club, Hollywood Alley, Long Wong’s Hot Wings, the Sun Devil House, and the Mason Jar.

The Puppets had played the Mason Jar since the early ’80s, but I’d never been in it. I knew the club because we drove by it on the way to high school many mornings. Of course looking back, I only wished I’d collected flyers from their earlier shows at long-defunct venues like Salty’s and Merlin’s on Mill Avenue, or better yet, went to those little local shows! In 1989, ’90, and ’91, I was only old enough to grab flyers. When my friends and I got our driver’s licenses, we frequented the same record stores on weekends and visits ones like Stinkweeds that we couldn’t reach on our bikes.

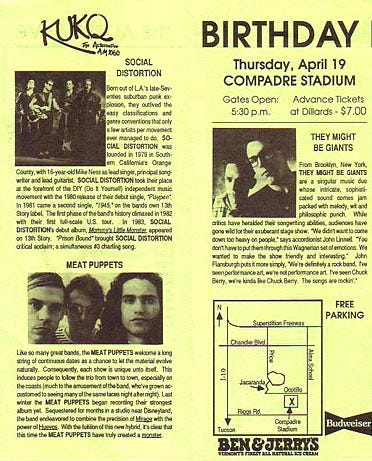

After orbiting the band for years, my friends and a 1991 concert turned me into a fan. The Puppets shared the bill at the local Q-Fest “alternative music festival” hosted by our local alternative radio station, KUKQ AM 1060. Crowded House played with the influential Pere Ubu, who were confusing and amazing, along with Richard Thompson, and The Candyskins, whoever they were. We came for The Wonder Stuff. My best friend JR had turned us all onto them, and this was the first show on their North America tour for their album Never Loved Elvis. They were incredible. But the Meat Puppets were just as energetic on stage, rawer, banging their heads the whole time, just whizzing balls of hair. They blew me away, even though it would take Too High To Die to turn them into one of my favorite bands and send me deep into their back catalogue.

After their set, JR and I prowled along the chain link fence that separated the backstage area from general admission, and there they were, the two Meat Puppets brothers who’d just played “Automatic Mojo.” The Kirkwoods stood smoking cigarettes in the dark. So we approached them and asked, “Are you the Meat Puppets?” They came closer and said yes, they were. “Would you sign our tickets?” They said: Of course! They were all smiles. Cris set his cig in his mouth and asked us our names and if we were having fun. Hell yeah we were, especially now. They took JR’s ticket and my flyer through the chain link fence and hung back in the darkness for a moment, scribbling. JR and stood there grinning, trying not to stare but unable not to. We shot each other excited looks. I’d rarely talked to any real musicians. When they pushed our stuff back through the fence, they wished us well and I literally waved goodbye—waved, like a dork.

JR and I shuffled out of sight. Over by a light, we greedily looked at our tickets. One Kirkwood wrote “Kill!” on one ticket. The other wrote “Destroy!” Oh my god, we said. How rad. That signed flyer became my prized possession. Until I lost it.

But that show and encounter left a big impression on me. Curt Kirwood’s own fleeting interaction with his beloved Jerry Garcia left an equally big impression on him. “[I]t’s just music and we’re just people,” Curt told an interviewer, “but there’s a few people that really stick out for me, and Jerry Garcia was definitely one of them. I remember here in Phoenix one time as they were walking off stage, and he walked right in front of me and we made eye contact and he was just like, ‘Hey man!’” Every fan knows that feeling. Music makes you want to get close enough to the musician to feel more of their energy, to brush just slightly against greatness.

As I started actually listening to the Meat Puppets, someone told me that one of the Kirkwood brothers went to my private Jesuit high school, Brophy College Preparatory, back in the day, but he got expelled when he rode his motorcycle through Loyola Hall, the school’s main building. He’d raced up one set of carpeted stairs, stalled on the landing, and ripped back down while leaving tire tracks on the carpet. After I heard that story, I frequently walked through Loyola on my way to and from classes and thought, These stairs? The same nasty red ones all those jocks trudged their Nikes on daily? These were the stairs where a priest and I spoke about the drawings he caught me making during his English class when I got bored. Those stairs became a sacred rock ‘n’ roll location that had no historical marker. Decades later, I couldn’t remember if that story was true. I vaguely remembered returning to campus during college to search for the truth, and maybe finding bassist Cris Kirkwood’s face in a framed graduating class photo hanging in Loyola. I’d walked the entire hall, searching the walls for him among the hundreds of students’ faces, and there he was: smiling, his hair standing tall in a poofy afro. Which would mean he didn’t get expelled. I could no longer remember if that was a real or false memory, but I preferred the motorcycle story.

What is true is that there was a record store called Tracks in Wax next door.

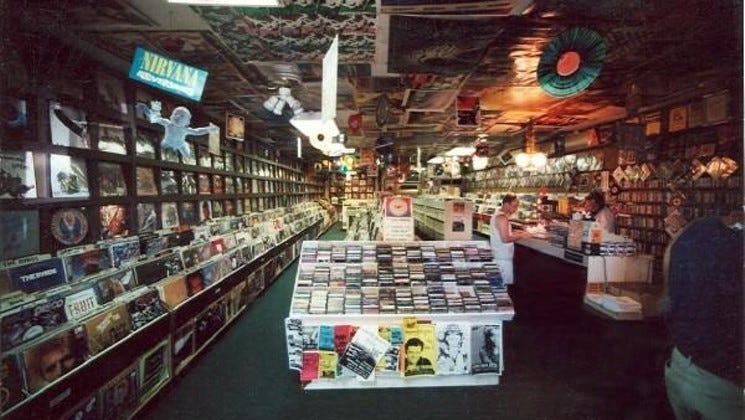

Before I got my license, my parents drove me to high school during my first two years, so I waited for them on the front steps after class. Sometimes I did homework and hung out with friends. Sometimes I went to the Tracks in Wax. It stood like a freak between a psychic and a nail salon, in a low one-story commercial strip. The long narrow interior had little natural light. Posters covered the ceiling. Wooden racks filled with twelve inch records lined every wall, and customers browsed under mobiles of colored vinyl suspended from strings. To a teenager, this felt like a place that had wisdom to impart.

Tracks in Wax sold cheap stuff and pricey collectibles along with tons of bootlegs. I was still learning about bootlegs. Bootlegging is an old tradition. Fans taped The Grateful Dead on reel-to-reel tapes and microphones set on stilts in the middle of dancing crowds. Fans taped Zeppelin and Dylan, sometimes in the audience, sometimes by patching into the venue’s sound system, as one fan famously did in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1969 on Zep’s first North American tour, and helped launch the black market bootleg economy. English pen pals had sent me copies of bootleg Depeche Mode recordings during my DM phase in middle school, but I didn’t understand how unofficial recordings ended up in stores like this.

Two brothers, Don and Dennis, opened Tracks in Wax in 1982. They both kept packs of cigarettes in the front shirt pockets. Sometimes they’d pull a wad of bills from their pockets to make change and have one of the kids who did inventory go get them take-out. Dennis was a grump. Smoking had dried his skin. He scowled a lot, tilting his head to look at you over the top of his glasses—not menacingly, just skeptical, as if too many school kids had destroyed his patience. As clueless kids do, I labeled him a dick. He definitely wasn’t cool looking like stereotypical record store clerks should be. Instead of wearing black clothes and sunglasses, he was a jowly, middle-aged man with dyed black hair who wore the kind of boring button-up denim shirts I refused to wear to Christmas dinner when my parents tried to make me. He had the same receded hairline that I didn’t realize I’d have in a few short years. Which is to say, I didn’t respect his surliness. Never mind that the guy had actually lived a life.

When I first started shopping there, I came to find Depeche Mode bootlegs. Wearing my DM tees and Birkenstocks, I thought I was the cool one. Unlike me, Dennis had actually earned his attitude. He went to tons of live shows, knew all the local musicians, and had a vast scholastic knowledge of 1950s and ’60s 45rpm records that complimented his brother’s knowledge of 1970s and ’80s bands. I avoided him and talked to Don instead.

Rotund and slow-moving, Don parked himself on a stool behind the register whenever I visited. He had a pinched nasal voice and you could hear him drawing breaths. Don was sweaty, scratching his pudgy forearms and lighting cigarettes. Only later did I learn what the sores on his arms were. But his disposition was sweet and visibly injured. Because he didn’t intimidate me, I quickly took a liking to him.

Some record store clerks, like Barry in the movie High Fidelity, make young customers feel inferior with their elitist tone and intimidating knowledge, acting like we offend them with what Barry calls our “terrible taste.” Other clerks enlighten customers, turning kids on to The Velvet Underground or handing them a must-have Big Star album the way Buzz Osborne turned Kurt Cobain onto to Black Flag and Flipper, and they save us from our own worst teenage impulses by directing us to the music we’ll appreciate later. Don didn’t turn me on to new bands initially. Once he found out I had every legitimate Depeche Mode recording, he suggested a bunch of bootlegs and then ordered more once I bought those.

Tracks in Wax kept their bootlegs mixed with the official releases, right in the open. I admired their subversive spirit and aspired to tell authority to fuck off as easily they did. They didn't give a shit. I also loved this place because you never knew what you'd find there, only that what you found would be cool. I had a routine: get out of class, rummage through the bins, see what I found. The store gave me the room to enter the world of adult music at my own pace, navigating and investigating without intimidation or smothering recommendations. Don ignored me until I asked for something, then he had a lot to say. Don never made me feel dumb for knowing so little about rock music. He never smirked judgmentally when I slipped through that front door again and again, looking for more of the same. He was an adult. I was a child. What did I know? He’d nod his head hello, maybe whisper a “Hey,” and let me scan the shelves. Predictable types were probably great for business, but he could see my curiosity, and once my tastes expanded, he helped expand them further.

As I outgrew DM in 1990 and got into rock ‘n’ roll, Don hooked me up with Jane’s Addiction and other bootlegs. The older I got, the more comfortable I felt talking to someone as knowledgeable as him. He’d stay wedged between the wall and register, and I’d lean against the counter to talk. He’d pull something out from under the counter that he thought was cool, or that I might like. “This just came in,” he’d say, his voice pinched, and hand me a copy of The Replacements playing live on Valentine’s Day, 1991. Or: “Check this out,” and hand me a soundboard bootleg of the Chili Peppers playing in LA in the mid-80s. Later on, I bought a copy of Bob Dylan’s famous Royal Albert Hall show, which Don said was cool but that I didn’t like until a decade later. The infamous Smokin’ Pig pirate label released the CD. The store always stocked tons of Smokin’ Pig bootlegs. This wasn’t like stores they had in New York or Chicago, but I wouldn’t have known about any of this music without Don. It was important stuff to know as the Alternative Era took over the world and rock music took over my life.

When the Puppet’s breakout album, Too High To Die, came out on a big commercial label in 1994, it became my favorite album. It spoke of other worlds. Sounded like no other. The lyrics suggested wisdom and a cosmology I was starting to unravel, and the music felt bright and cosmic. Because Kurt Cobain called them “The Brothers Meat” on the MTV Unplugged performance, I called them that, too. After they played with Nirvana, the Puppets were suddenly getting interviewed everywhere: MTV, late night talk shows like Conan O’Brien, mainstream magazines. The band whose weird flyers attracted me as a kid were famous enough to play David Letterman. Their Phoenix origins became a point of pride: These cosmic travelers came from our sprawling boring town. These people who influenced Nirvana, from Phoenix! Yeah, Buck Owens lived in Phoenix for a while, and so did Dave Mustane from Megadeth, who was a dick, and the coolest of all, Stevie Nicks. Of course, the popular 1950s instrumental guitar twanger Duane Eddy grew up south of here. And Phoenix’s Jimmy Eat World Gin Blossoms got famous for a second. But as far as we were concerned, nobody famous or cool came from Phoenix except the Meat Puppets. And no band made me more proud to be a Phoenician than the Meat Puppets. They were proof that our maligned, scorching hot city had some culture, proof that you could sit in the same classrooms as I did at my Jesuit high school and one day end up on stage with Nirvana, the most popular band in the world, if you kept at it: creating, touring, promoting, imagining, tirelessly pushing your own artistic vision. But the art of music often clashes with the business of music, and things can sour when you’re in top form.

But even in the throws of the Meat Puppets’ lysergic influence, it took decades to recognize the lesson of this innovative band’s only philosophy: Forget genre, like what you like. After they outgrew their original punk rock sound, the Puppets embodied the true punk spirit, which isn’t about clinging to genre or styles of clothes, but is all about thinking for yourself, self-definition. For the Puppets, that meant expansion. It meant dissolving genre distinctions and absorbing any appealing musical influences, to create something unique that defied boundaries and pleased only themselves.

Covering John Denver’s “Country Road” and the C&H Pure Cane Sugar commercial jingle, all while writing distinctly original songs with warped names like “Enchanted Porkfist”—nothing’s more punk than shamelessly embracing what you like. Only after my formative teen years passed and my hard parts softened did I see how the Puppets’ genre-defying style charted a way to live my own life.

When an interviewer in the ’90s asked how Puppets guitarist Curt Kirkwood would categorize his band’s music, Kirkwood said that rock ‘n’ roll had so many subcategories that categorizing no longer mattered. “The proliferation of branches is gonna become so dense that it really means nothing, eventually. I think we’re world beat, actually.”

The interviewer faced the camera. “World Beat,” she said. “I like that. So you’re going to take over the world.”

Grinning, Kirkwood said, “Pretty much, yeah. I don’t exclude any influence.”

That, not punk rock credibility or fantasies of youthful freedom, was true liberation.

But back in 1994 and ’95, I listened to Too High to Die constantly and still thought genre allegiances mattered. I was a rock dude. When their follow-up No Joke! came out, I was stoked. Even though fans don’t talk as much about it as they do other albums, it’s one of their best. Curt was right: It’s a lost record. Granted, it has a horrific cover, but still. Despite its dark overtones and minor keys, it has incredible, memorable guitar riffs like on “Taste of the Sun,” gorgeous Kirkwood harmonies like “Chemical Garden,” and ripping solos that would fit on Too High To Die. Curt delivers classic Curt lines like “Touched by some hand / Born stupid / There's no way that I’ll ever win. People think of II as a desert album, but No Joke! is the perfect album to drive through the desert to. Songs like “Predator” and ominous sing-alongs like “Sweet Ammonia” really deserved their chance to circulate widely the way their single “Backwater” did, but things weren’t going well for the band at the time.

While touring with then-popular Stone Temple Pilots, huge bags of cocaine were always around, and Cris got too into it. The band played all the popular TV shows of the era: David Letterman, Conan O’Brien. Meat Puppet CDs started to carry a sticker with a quote from Kurt Cobain, citing the band’s influence. But just as the band’s proverbial star reaches its zenith, the band started to dissolve, turning back into the same cosmic dust that their songs were made of. Soon they just disappeared. No tours. No new albums. No news about what happened. After decades of pounding the pavement, decades of posting psychedelic fliers everywhere you looked, the Puppets were suddenly gone.

When I moved back to Phoenix after graduating from college in 1999, Don was still sitting at the counter. We talked bootlegs a lot. One day he pulled out a book from under the counter called Bootleg: The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry, by Clinton Heylin. “You’ll like this,” he said. Then he lent it to me to read. When I brought it back months later, my mind blown on this secret history, he said, “Just keep it.”

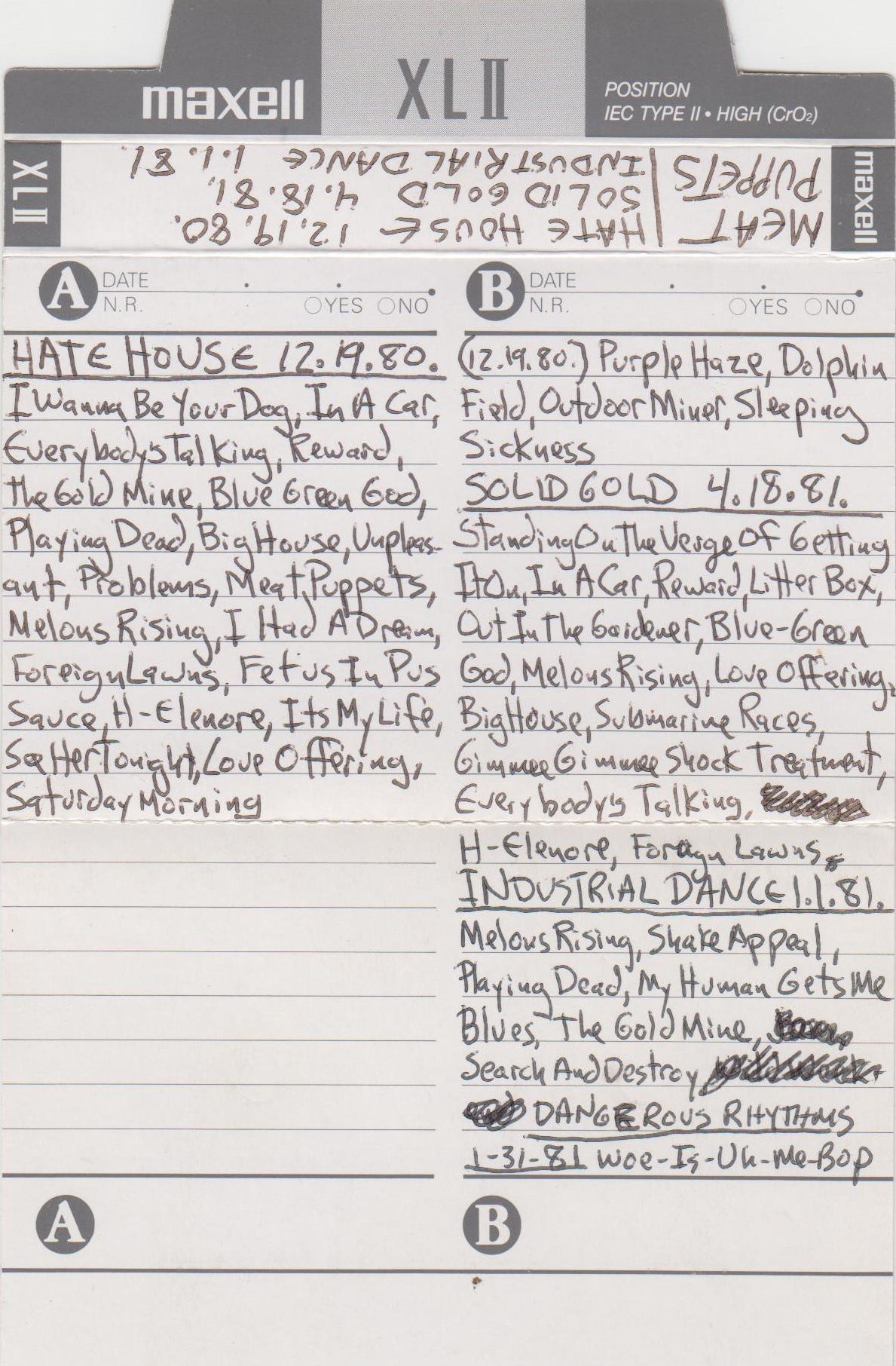

When Don found out I loved the Puppets, he pulled a box from underneath the counter and handed me six cassette tapes. They were live soundboard recordings that drummer Derrick Bostrom had copied for him. Dating between 1980 and ’84, the live recordings contained shows from defunct Arizona clubs like Star System, Solid Gold, Industrial Dance, and Hate House, even a house party, and they covered the band’s earliest years and the fertile period when they transformed from a punk band to a psychedelic band on their incredible Meat Puppets II. One tape was labeled “spring 1980 demos” and featured covers of The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” The Ramones’ “Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment,” Black Flag’s “Class War,” Neil Young’s Cinnamon Girl,” and Magazine’s “Shot By Both Sides,” none of it officially released.

“Take them,” Don told me. “Make copies, and bring them back when you’re done.” I was floored. He believed these were a good introduction to early Puppets and a way to show me that, as much as I wanted to move away from Phoenix, there were things about our city to appreciate. His kindness changed my listening life. I still feel indebted to him. When I brought back his tapes, he wasn’t there to receive them. He wasn’t at the store the next time either. That fall, I moved from Arizona to Oregon and never saw Don again. He apparently passed away. I still have his tapes.

Listening to those tapes was like discovering another planet. Live, they opened shows with Ma Rainey’s “See See Rider.” They mixed their hallucinogenic original “Aurora Borealis” with The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows.” and paired Slim Whitman’s “Una Paloma Blanca” with Pink Floyd’s “Astronomy Domine.” I’d never heard of half their covers before, and until I had, I didn’t fully understand the band’s aesthetic or approach. I didn’t even realize that some of their songs like “China Cat Sunflower” weren’t theirs. They were Grateful Dead songs, so I started listening to the Dead and found things to love rather than make fun of.

Bostrom’s live tapes also contained what the weird side of my seemingly dull Phoenix sounded like. Here were sonic photographs of what culture was happening when I was still playing with Star Wars figures. Here’s what it sounded like inside all those early Phoenix and Tempe clubs that closed before I’d ever gotten old enough to appreciate the bands who played in them. It was unbelievably cool.

Traders and fans had circulated other live Puppets tapes for years, and the finally, Derrick Bostrom posted some on his website. And fans shared others on Archive.org, which contained the biggest selection. But until I digitized them, I never saw the shows Don gave me in circulation anywhere. Introducing 1982 soundboard recordings from Salty’s and Merlin’s, one generous tape-trading fan detailed the story of how these recordings, and the ones Don gave me, came into circulation. They came from the collection of fan named Dave Homes:

…These shows represent some of the earliest material to surface from the Meat Puppets, and they are quite spectacular.

The story goes that a friend of Mr. Homes worked at a local record store in Phoenix and got to know Derrick Bostrom pretty well; well enough fer Derrick to give him live tapes of the band. Since Dave then was able to transfer them straight from the tapes Derrick gave out, and not from his pal’s copies, these are the lowest generation around.

Now, figuring that Derrick was (and still really IS) the archivist of the original band, these are almost certainly from 1st generation tapes. Since there are usually a couple of shows (or excerpts of shows) on each tape, we can kinda deduce that Derrick made copies from his masters, making these most certainly 2nd gen copies…in other words, pristine.

The tapes were labeled, which really helps when yer dealing with early Meat Puppets shows, but, but some tapes contain a couple of excerpts of shows that were only labeled by date. Until further info can be brought to light on the filler material, which I’ll seed separately, all known info will be given in the info files of each seed

There are a bunch of these, so I decided to seed them in Volume sequence for you to keep track of what ya have and what ya may want, especially those who want to get them all. They are, fer Meat Puppets fans, true Holy Grail material…

Please note, no enhancement has been done to these recordings. I may have been able to tweak some minor dropouts and eliminate hiss and some other minor stuff, but I left them as is. As always, azimuth correction was applied ensuring the best transfer possible, but that is it…

To me, these recordings capture not only the early days of the band, but the early days of the Phoenix punk scene, just as Tony Victor, who later founded Placebo Records, was beginning to book local bands, and eventually, out of town punk bands passing through to get to L.A.

The gorgeous melodies and intricate song structures are still here, ya just may need to listen little harder to decipher them fer the folks who only know the later stuff…or not at all (is that possible?)

I certainly don’t look at the early band as one still trying to find their niche, as some folks may. The ‘break through’ Meat Puppets II, while still containing some of the reckless abandonment of the earlier stuff, refined the sound a lot. Yet these recordings prove, without a doubt, that they were always a great band.

Meaning: Dave worked at Tracks In Wax.

After that, I tracked down as many live Meat recordings as possible. Bostrom made that easy by posting a bunch from his collection online. The best live recordings had more fire than their best studio albums, because the guitar solos were imaginative intense, the banter hilarious, and the variety of covers songs was staggering and only available here.

With a name like Meat Puppets, it’s natural to dismiss them, but no one can ignore their musicianship. They’re incredible musicians. They learned so many cover songs that they seemed to play different covers at every show on every tour. Their live archive contains few duplicates. And you can’t separate the size of their repertoire from their ability to interpret those covers in their own way. They had such imagination. You could assemble entire Puppets playlist albums composed only of cover songs. In fact, I have. I made another album solely of their country music covers. I don’t think any band in history mixed those kind of chops with that kind of warped imagination the way the Meat Puppets did.

Listen to their 1990 cover of “The Penny and the Pole.” It embodies their entire approach: Musically, each instrument is locked is tight. But the band’s still loose, so happily messy—the cartoonish, spazzy harmonies of Cris behind Curt, barking out words like a cartoon Disney dog. It’s serious. It’s a joke. It’s catchy and bad ass. It’s easy to wonder if they’re celebrating these old country tunes or laughing at them? But Curt loved these songs, and their appreciation is serious, but their spirit is punk. Their tongue’s in their cheek, because they never took anything too seriously. No one pairs psychedelic guitar solos with serious country music like Curt Kirkwood. “The way that we play stuff is way more Sedona than Texas,” he told me. “We know where the vortexes are man.” You can’t play that loose—can’t deviate from the song’s structure to improvise or explore—unless you are that tight of a musician. It takes chops to play that light and free. They’re not loose because they’re sloppy. Their loose because they’re skilled.

Curt’s guitar playing makes it easy to miss his powerful lyrics, which reveal a profound attention to Nature and the kind of revelations that psychedelics can afford: songs like “Leaves,” “Aurora Borealis,” “Another Moon,” “Whirlpool,” “Swimming Ground,” “Two Rivers.” In “Leaves” he drops lyrics so wise, so cosmic, they leave your head spinning while the song charges on to the next revelation.

Who ever made up the calendar was wrong

It’s new year’s all year long

Each year is a minute

Only full of the leaves in it

The Meat Puppets never wrote a love song. Kurt told me himself. But a few of the songs they covered were about love, like The Marcels’ 1961 hit “Blue Moon.”

Blue Moon, now I’m no longer alone

Without a dream in my heart

Without a love of my own

Performing “Blue Moon” at Tempe’s Sun Club in 1990, Curt plays it straight. He clearly loves the melody, its old pop sweetness. Maybe he liked it from childhood. He was born in 1959, so two years old when the song hit the radio, but maybe he heard it as a kid and liked it. When he played it at the Sun Club in 1990, he was an unground rock icon, weird and handsome. And he was only 31. Thirty-one was impossibly old to 20-somethings like me in 1990. But I didn’t think of my musical idols that way. Thirty-one is actually young. Do-wop and golden oldies seemed like music for old people, but the Puppets were cool enough to turn that into psychedelia worthy of a young punk’s time. He takes the solo so seriously. What he plays is gorgeous, tender, haunting. It’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard. It sounds like childhood, the way innocence feels. It’s the solo that would play while two teen lovers walked through a park in 1959. And he takes its beauty seriously. Even as he flubs the lyrics and does his fuck-it-all Kirkwood mumble, he keeps the solo pure golden sunlight. That’s why listeners like me were excited about the 2007 Meat Puppets reunion.

The Millennium fostered a reunion renaissance: Pixies, The Stooges, Dinosaur Jr. “I’m sure that’s lucrative for them,” Curt told me. “There’s no guarantee for the Meat Puppets that it would be lucrative.”

“The Meat Puppets have always done what they’ve done and never been very popular,” Cris said in a 1994 Boston Globe article, “but we’ve been popular enough to keep doing it. I’ve always considered myself really fortunate.” According to his then-girlfriend’s 2004 blog, Cris felt like a failure for becoming “the guy that wrecked the Meat Puppets.” But once Curt learned of Cris’ recovery, he played some new songs over the phone, and they started rehearsing.

“Cris was pretty much, very very adaptable to the situation.” Curt told me. “He understood I wanted to have a fairly autonomous reign on what was goin’ down this time.” Cris didn’t have trouble remembering the songs. Both Brothers had to relearn things. “That’s the nature of having a large catalog,” Curt said. “I don’t remember a lot of stuff.” Like “New Leaf,” the song he recorded for Rise but previously released on Golden Lies. “It’s one of those things that you just go, ‘Oooo.’ But it’s a different arrangement,” he snickered, “so I forgot.” Performing in public doesn’t scare Cris either. “He’s been in fuckin’ federal penitentiary. If anything’s gonna make you nervous it’s being around a bunch of murders and thugs like that.” Curt’s philosophy now is: “We just wanted to make a record pretty much for ourselves and for anybody who wanted to hear it. We don’t have any ambition. We don’t have anything to prove. We figure, you know, we’ll probably be given whatever we’re due, because we have a good name and if we play good people will kiss our asses as much as we deserve.”

As usual, Curt wrote all their new album’s material, some of it having laid around for years. Surprisingly, Curt plays drums on nearly half the record, even drums andbass on three tracks. Although asked to participate, Derrick declined the invitation, favoring the settled pace and steady pay of a Phoenix Whole Foods market. Luck delivered Ted Markus, a New York-based engineer doing audio on a Puppets documentary. Markus, drumming since age eight, previously played with two New York bands and owns a sizeable collection of live Meat recordings. “Nothing needs to be filled in,” Curt said. “He knows the stuff better than Cris and I do easily.”

Interviewed for a 1993 PhD dissertation, Derrick described touring as a drag. “You drive all day and eat shitty food and take weird hours,” he said. “Nobody likes living out of a suitcase.” But his other interests had also started assuming importance. Jazz clarinetist Artie Shaw’s autobiography, The Trouble with Cinderella, seemed to resonate with Derrick because Shaw, Derrick explained, “kept saying, ‘Man, if I could only get a lot of money I would just quit.’ And he finally realized that he was in the weird vicious circle.” Yearning to write but feeling trapped, Derrick says Shaw eventually “gave up music and began to write.” Having overseen the Rykodisc reissue of the Puppets’ SST albums, Derrick spent his time traveling, hosting a web-radio show and the Puppets’ website. Time had also revealed his own love of writing, in the form of a voluminous and eloquent blog covering everything from Scottish castles to classic country. He also collected stamps.

“[If] if you get out of the business,” Curt told me, “and a lot of people will tell you this, it’s hard to get back in. It’s hard to get your head back in it.” As much as he wanted Derrick onboard, Curt knew, “If somebody hadn’t played the drums in ten years, they’re probably not playing the drums very well.”

The band raged that night I saw them in Austin.

After banjoing through “Lost,” Cris shouldered his bass, Ted hit the floor tom, and fans screamed to a blaring “Lake of Fire.” “Where do bad folks go when they die?”

“People notice when you’re away more than you do,” Curt said.

Hearing the new songs live, it hardly felt like a year, let alone 11, had passed.

Years after the brothers’ reunion in Texas, I still had Don’s cassette tapes. I wanted to give them back to drummer Derrick Bostrom. What if these were the only copies in existence? What if he hadn’t made dupes? Bostrom eventually rejoined his old friends on stage in 2017, when the Meat Puppets got inducted in the Arizona Music & Entertainment Hall of Fame. Thankfully, he even resumed touring and recording with them in 2018 in a band that now included Curt’s talented guitarist son, Elmo. But at this time, around 2009, Bostrom hadn’t spoken with the Kirkwoods or played drums in years, preferring his quiet steady life in Phoenix off-stage.

So I kept made copies and tried to drop off the tapes for Bostrom at his Whole Foods, but he wasn’t working during my two visits. I asked other staff if Bostrom was around. I explained I had some recordings to give to him, his recordings, but coworkers treated my request with caution and all shook their heads. “Employee schedules are confidential,” they said. Clearly they understood the effect of their coworkers’ old musical life. Maybe other fans had bothered him before. Maybe they were just protective.

I went to the produce section, which is where Curt said Bostrom worked. A guy in an apron was stacking fruit. I said I had some ancient tapes from his coworker Derrick Bostrom and wanted to return them. “He doesn’t know me,” I explained in a way that must have sounded stranger than I’d intended. Then I rattled off something that may or may not have come out like: “I’m an old fan. I wrote an article about his band. These ended up in my possession and I thought he might like to have copies. For his archives.” I don’t know what I said. His hard suspicious stare made me nervously ramble.

“Sure,” he said nodding his head. “I’ll pass that info along to him.” He stared at me suspiciously, studying my face as if it would reveal some sign of my character, some hint of my true intentions.

“That’s fine,” I said. “I understand his need for privacy.” I thanked him, bought some fruit, and clutched the tapes. Then I left.

I really enjoyed the article, and I can really relate to it as I grew up in the same period but in southern California. Rage against the machine was my Meat puppets, as were Janes, Mary’s Danish, Liquid Jesus, and so many others. Thanks for writing this! I came away with the knowledge that so many little seemingly unimportant places,people, and things, can have a profound effect on a kid growing up. I remember my tracks on wax was alternative groove in hermosa beach, and Lou’s records in San Diego county. I kept all my ticket stubs and flyers from 1990-95 and have them tucked away. I also got to meet some of my musical idols and was trusted with some original master tapes of a band I’m sure you would know. Anyways , I have to ask what is the story with Horace Pinker? They were on the nil for almost every show and I have never heard of them. Reminds me of some similar bands in LA that would play at all the great shows but remain forgotten in rock history.

"We know where the vortexes are man" -- great stuff, Aaron!