Unity and Resistance: The Message of Bad Brains

Revolutionary times call for revolutionary music

Those of us who love the Bad Brains always will love Bad Brains, but America’s continued, vocal protests to end the violent, systematic oppression of Black Americans have revitalized the band’s message of unity and resistance.

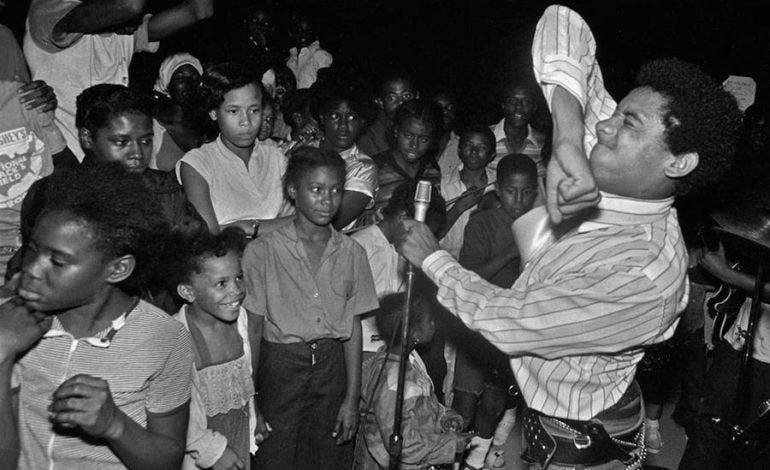

Founded in 1977 by four Black men in Washington D.C., Bad Brains blends punk, reggae, metal, and funk, a mix you hear most across the course of their first three landmark albums, Bad Brains, Rock for Light, and I Against I. Darryl Jenifer plays bass. Gary “Dr. Know” Miller plays guitar. Earl Hudson plays drums, and Earl’s brother Paul “HR” Hudson sings. HR stands for Human Rights, which tells you where they’re at. During 40 tumultuous years of playing and breaking up, their revolutionary unit pushed rock music’s sonic and racial boundaries and inspired countless musicians.

“If you ever saw the Bad Brains live, it’s not something you would ever forget,” D.C. filmmaker Scott Crawford told WTOP News in 2016, 39 years after their formation. He first saw them perform when he was 12. He later included Bad Brains in his 2014 documentary Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, D.C. “It changed my life, and anyone that’s ever heard the Bad Brains, or seen them live, would probably say the exact same thing.” That includes me, a Jewish kid from Arizona. And it includes influential artists like Fishbone, Beastie Boys, Lauryn Hill, The Roots, Wu-Tang Clan, Smashing Pumpkins, and Living Colour—to name a few.

The Cars’ singer Rick Ocasek loved Bad Brains’ debut cassette so much that he played it on tour to get psyched for shows, then he asked to produce the band’s second album, Rock for Light, in 1983. A single Bad Brains show turned Black Flag’s Henry Rollins into a singer. Bad Brains’ approach to life pushed Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye to be more dedicated to his ideals as a working musician. Kurt Cobain included Rock for Light on a list of his top 50 albums that he wrote in his journal, and Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl learned fills by listening to Bad Brains’ drummer Earl Hudson. As Vice put it: “Calling Bad Brains influential to late-20th century rock music is like calling Abraham influential to Western religion.” They’re also just one of the greatest rock bands of all time, and predictably underrated. “If they’d been on a major label and H.R. had kept it together,” producer Ron St. Germain told the Washington Post, “they could have made a major mark as a pioneering group in the fashion of Led Zeppelin.”

Their influence is two-fold.

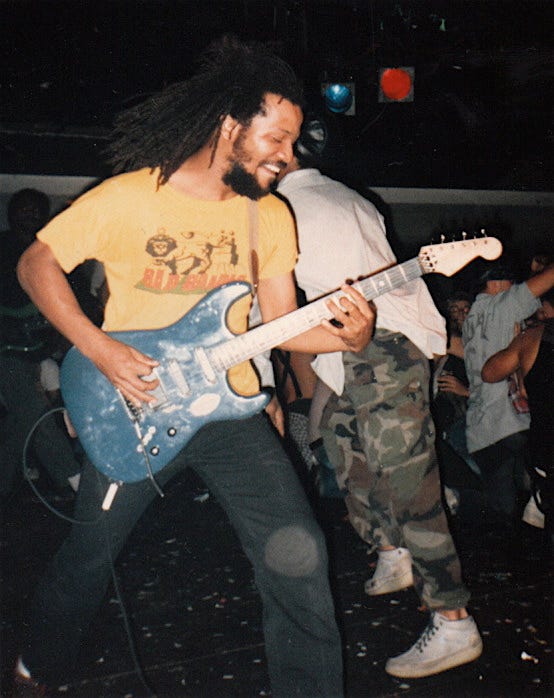

First there’s the music. Bad Brains play punk songs alongside reggae. Precise, passionate musicians with jazz roots, their early live sets tore through dizzyingly fast tunes whose lyrics were screamed by the charismatic, stage-diving singer HR, only to suddenly switch to buoyant, mid-tempo reggae jams. “They’d do their hardcore,” their Saint Germain told Vice, “and then they would just kind of turn a page and it was instant reggae mode.” They played covers like “I and I Rasta” and original reggae tunes like “I And I Survive” and “The Meek.” Dr. Know’s twinkling guitars on tracks like “I Luv I Jah” will make you tingle, while HR’s tenderness and range will make you cry. Jamaican music had influenced the sound and DIY business practices of early London punk bands like The Clash, but before Bad Brains, no Black American bands played punk and reggae.

The second reason is the band. Bad Brains’ racial composition and essential hybridity challenged racial stereotypes and America’s idea that riff-heavy rock was white music, because Bad Brains’ memorable songs proved otherwise. Their scorching performances garnered instant respect and the envy of fellow musicians. People watched and wondered how anyone, Black or white, could play that fast and that precisely. Most first wave punk bands were sloppy or limited in their abilities. In a very white punk world, Black punks had to carve their own space.

As the Hudson Valley, New York news outlet Echo Sixty6 wrote:

“Punk music is not the sole property of whiteness, even though to people of my generation it may appear that way at first glance. Like many facets of pop culture, its historical image has been whitewashed,” writes Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff for Dazed, pointing to Bad Brains as “obvious co-conspirators.”

Brinkhurst-Cuff continues: “In many ways, Black people were the original counter-cultural figures, racially excluded from a domineering white society, albeit not out of choice. Our music and culture has been intimately linked with the punk genre since its inception.”

In an article for PROHBTD, entitled “The Very Black History of Punk Music,” [journalist, producer, and filmmaker] Sacha Jenkins adds, “I’m not saying Black people created punk rock. I’m saying we are punk rock without even trying.”

“Back in that time,” bassist Jenifer told Vice, “a cat like me from D.C. was supposed to play funk, a cat from Jamaica’s only supposed to play reggae, and a white cat’s supposed to play Zeppelin… But for Bad Brains to jump out and be this punk rock band and push it the way we did, I can see that we were used as a tool to spread the spirit of versatility. The Beastie Boys started rapping, The Chili Peppers were funky, all of that—‘Well damn, if these black dudes from D.C. can be a punk band, maybe me, a white dude, I could be an ill rapper.’”

Bad Brains empowered many musicians to follow their artistic vision. “They were going into a different area, the rock vein, on [I Against I],” Fishbone’s lead singer Angelo Moore told Vice, “and I like what their music evolved into. And plus, as a Black man playing rock ’n’ roll in America, hearing them was liberating. ‘This is what we’re gonna do, and we’re gonna stand for it no matter what anyone else says’—that’s the feeling I got when I would listen to that album.”

“We represent fearless creativity,” Jenifer said in a 2019 interview, “void of race, creed, color—all the isms.”

Bad Brains didn’t set out to play rock and reggae. It wasn’t some concept to distinguish themselves in a formulaic genre. “It was what the Great Spirit had in the wind for us to do,” Jenifer told one interviewer. “It’s the Great Spirit making us go, ‘You could play go-go or funk, but then you could play whatever the hell you want!’” Their original singer Sid McCray played them The Ramones and the no wave compilation No New York in the late-70s, and the musicians were taken by the musics’ energy. “When I discovered punk rock, I was attracted to it because it was free in every way,” Jenifer said. “We just had the essential albums of punk: The Sex Pistols, The Damned, and The Dead Boys, and we took it from there. H.R. really liked it, and we jumped into being punks—leather pants and all that. I really liked punk because I was shy, but once I saw people who couldn’t play were playing it, I was like, ‘Fuck that! If these dudes sound like this, I’m going to sound like a monster!’”

Rasta entered their life in a way that the members view as destiny. In 1978 they went to see jazz-fusion bassist Stanley Clarke perform at D.C.’s Capital Centre, opening for Bob Marley. The guys weren’t into Marley. But his performance blew them away, and as they began studying Rastafarianism, it became the center of their personal and musical lives. As evolving artists, they quickly outgrew punk rock and pulled in dub, soul, hair metal riffs, and funk’s rhythmic sensibilities. For a time, bassist Darryl Jenifer was more inspired by Winger than punk. By expanding their sound, they created hardcore. Their album I Against I helped create funk-metal. Asked how they’d describe their music in 1990, Dr. Know didn’t use the terms fusion, hardcore, reggae, or punk. He said, “Actually, we just play Jah music—Jah Rock.” Jenifer doesn’t even see most of their music as punk either.

“I was only a punk or interested in punk rock music for a year—maybe two years—as a teenager,” Jenifer said in a 2019 interview, “it’s interesting how some things can stick with you, or become you. I remember when Bad Brains was called hardcore, I was like, ‘Really, what’s that?’ I actually recall thinking it was porn related, so when you say I am a pioneer of punk I think, ‘Damn, I wonder what Johnny Rotten thinks of that?’ I consider myself a multi-styled instrumentalist, known for a brief encounter with punk rock as a teen.’” All the members have what Jenifer calls the “blessing of versatility.” Fast, furious, serene, transcendent—their multifaceted musical personalities even caused internal tensions between the members who wanted more metal and the members who insisted on a less aggressive sound. They sang about the unity of all people, and they modeled that ideal by merging musical genres into a unified sound, showing how seemingly disparate styles could coexist as one. This message is arguably their most important.

It’s easy to focus so much on Bad Brains’ ground-breaking music that you miss their role as activists. Their music is their activism, because their music is their message. As Rastafarians, they don’t play reggae to cool down between fast songs or to let the audience catch its breath. They play both styles because there’s no separation between their spirituality and themselves. Jenifer calls his band “The thinking man’s punk.” A lot of HR’s lyrics center around the Bible as interpreted by Rastafarianism, and an idea that the band famously calls PMA, or “Positive Mental Attitude.” “So we know our message is that of peace and love and Positive Mental Attitude,” Jenifer said. “That’s what we really stood and stand for.”

“The punk music of England was informative,” guitarist Dr. Know said in the 2012 documentary Bad Brains: A Band In D.C., “but it was more like, you know, ‘Fuck this, fuck that.’ We wanted to try and give an alternative and unify the people: ‘Yes, we can make a change if we unify people,’ as opposed to just saying, you know, ‘This is screwed up, and that is screwed up, and that’s just the way it is.’ I think that was the difference, initially, in our message: just being positive as opposed to destructive.”

“When we first came out, [punk] was kind of on some vulgar shit,” Jenifer told one interviewer. “We started kicking PMA in our music, and the message was different than the regular punk rock. You know, a punk rocker can write a song about hate—I hate my mom or some shit, you know? We wasn’t on no shit like that. Some kids who wanted to see some regular shit saw us, and every kid’s heart and mind was opened. It’s like you’re just going to see some regular reggae music, and Bob Marley is playing. You might walk away from that and go, ‘Damn, that’s some consciousness in this music.’ When we would play, you’d see, [sings] ‘I got that PMA,’ and there was a whole mode of consciousness that was coming through it.”

PMA comes from Napoleon Hill’s 1937 self-improvement book Think and Grow Rich, which claims “Nothing great was ever achieved without a positive mental attitude.” Hill presented billionaire industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie as a model for how ordinary Americans could use positive thinking to achieve both financial and personal greatness—not by simply visualizing ones’ own success to make it come true, but actually living with what he called a Positive Mental Attitude. HR’s dad gave him a copy of Hill’s book. “And it made sense,” HR said in Bad Brains: A Band In D.C., “to stay positive, not to worry, and it would show how people who refrain from living violently will get a good response.” Part of the message for HR was the importance of having something to believe in. Decades after first reading that book, HR still had a key quote memorized: “Anything the mind can conceive and believe, the mind can achieve.”

“The philosophy in essence, man,” Earl Hudson said, “was really about God, about the Lord, but it also was a thing where you have to make a plan in life, and you have to visualize this plan. But it was all about keeping a Positive Mental Attitude, you know?”

“What we discovered was PMA was really the Great Spirit,” Jenifer said in Wax Poetics. “PMA—that was big on us. That would keep us cool in the hood. And then, guess what PMA was? It was Rasta. It’s like an advancement of a concept about making money being pushed into, ‘Okay, now there’s a Black Jesus,’ so to speak—something I can identify with in terms of spirituality.”

When their spirituality and ideology fused with fast music in the early ’80s, it became what their live EP called “spirit electricity,” and what Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid called “a kind of spiritual anarchy” that “was literally a religious experience.”

John Joseph, singer of the New York hardcore band Cro-Mags, personally witnessed HR’s religious devotion in Bad Brains’ early days. “He traveled with such a conviction, spiritually,” Joseph said, “to his beliefs, and lived it. He wasn’t just talkin’ shit. He was livin’ it. He was getting up every day and meditating and reading the bible and living the life.”

Singer Israel Joseph, HR’s brief replacement in Bad Brains, said, “Now what is HR? A prophet, a man who leads people spiritually. He is a shaman.”

“Just like what Bob [Marley] shows us,” HR said in a 1989 interview, “music is gonna teach the people a lesson.”

Classic Bad Brains song titles like “Rock for Light,” “Coptic Times,” and “Right Brigade” convey a clear sense of cosmic purpose. Many songs like “The Big Takeover” position the band against oppression and fascism, and challenge everything that is so fundamental and flawed about America: racism, classism, materialism, and spiritual vacancy.

On recording of a 1985 show in San Diego, a voice that sounds like Darryl Jenifer’s tells the crowd: “We’re mad because there are still slaves on the planet, so…Just know that if you want.” Then ty tear into “The Big Takeover.”

All throughout this so-called nation

Prepare yourself for that final quest

The world is doomed with its own segregation

Just another Nazi test, yeah.

The big takeover

In addition to the actual enslavement, possession, and subjugation of Black people, too many of us so-called “free” people remain slaves to our ideas, our wealth, greed, hatred, complacency, and possessions. That capitalistic, materialistic life is a fantasy that HR compared to “living in a movie.” Many lyrics were calls to action, like “At the Movies,” which encouraged listeners to dismantle the fantasies Americans hid themselves inside: “Doesn’t matter what they say, never give in, never give in.”

At Pitchfork Eric Carr described the 1979 song “Pay to Cum” as the band’s “famously anthemic, idealistic tirade against systems of control and the prevention of free expression.”

In “Fearless Vampire Killers,” HR builds his lyrics around Karl Marx’s infamous comparison of capitalism to vampirism. “Capital is dead labor,” Marx wrote, “which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.” HR sings:

The bourgeoisie had better watch out for me

All throughout this so-called nation

We don’t want your filthy money

We don’t need your innocent bloodshed

We just wanna end your world

HR’s indictment of American capitalism and me-me-me culture in “I Against I” still ring too true:

In the quest for the test to fulfill an achievement

Everybody’s only in it all for themselves

When the fact of the matter is they just don’t care

To extend a helping hand to anyone else

So tell me why, did you have to lie

And try to make me all confused about the U.S.A.

When the fact of the matter is you just don’t care

To comprehend or understand a single word I say

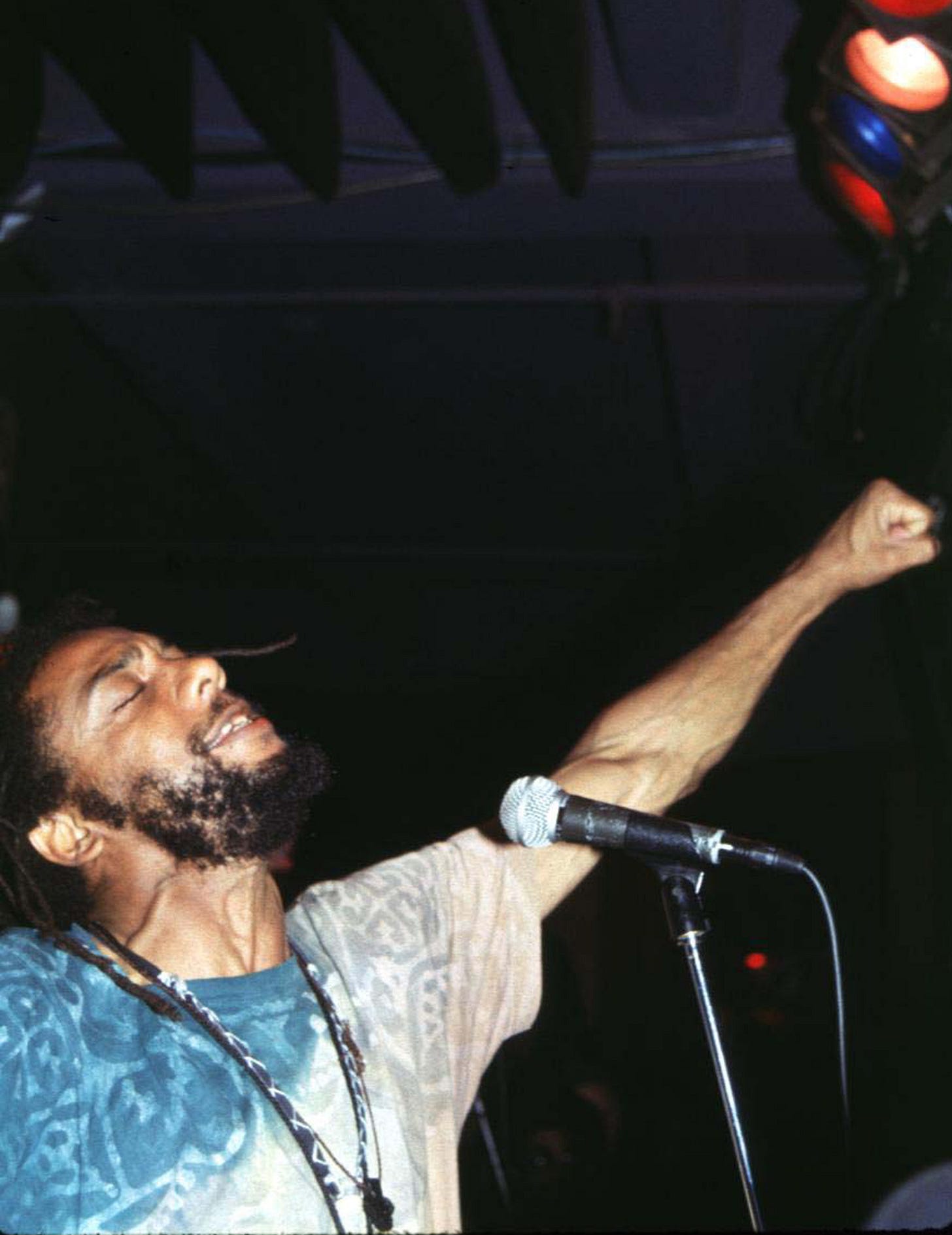

In addition to being a formidable lyricist, HR was one of the greatest lead singers in the history of rock music. “Nobody sounded like him,” producer Ron St. Germain said in Finding Joseph I. “Nobody moved like him.” Yet his unbelievable stage presence rarely gets mentioned alongside the usual greats like Iggy Pop and Prince. Lithe and aggressive, during the band’s heyday in the 1980s, HR dove off monitors, engaged audiences from the start of the first song, pounded his chest, danced so his head moved at different frequencies than his hips, legs, and hands, as he swung his dreads back and forth. Watch him move at the 7:22-minute mark at this 1987 performance. Or how he ends songs with a backflip. He did that regularly. “HR and Iggy Pop,” said Black Flag’s Henry Rollins, “to me, are the two most charismatic, I-want-to-be-that-dude frontmen I’ve ever seen.”

Along with singing, HR sometimes just spoke his message to the audience between songs, chanting: “Black and white, we come to unite! Black and white, we come to unite!”

Many of us fans received the message. The band tee I’m wearing while typing this has a small PMA patch on it, and I rarely wear band shirts. Whether or not HR is a prophet, his is, like Israel Joseph said, a man who leads people spiritually. I’m one of the people he’s help see.

I first discovered Bad Brains in high school. I listened to punk rock in middle school, because that’s what we skaters did, but bands like Circle Jerks, Dead Kennedys, and JFA didn’t speak to me. So much of punk was unimaginative and predictable, like formulaic television. The adolescent lyrics rebelled against the empty, fleeting enemies of youth or the Regan Era’s obvious symbols of repression. I liked fast loud guitar music, but I also liked melodies, harmonies, something more complicated that what passed for punk. Then I found Bad Brains.

They gave me music and a sense of perspective. They weren’t more angry youths abiding by punk codes. They were artists and thinkers. As people of color who grew up in racist America, they had reasons to be angry. And yet they weren’t simply angry. They were spiritual. Their complexity challenged you. Initially their melodies and guitar riffs gripped me. Soon I heard how they were empowered, welcoming, and striving for something beyond the physical realm, and they wanted to get listeners to reach for it, too.

I’m firmly Gen X. I can still hear the magic in my favorite albums from high school. Meat Puppets’ II, Jane’s Addiction’s Triple X, A Tribe Called Quest’s Midnight Marauders, and Smashing Pumpkins’ Gish permanently expanded my musical taste and, like all music in our formative years, imprinted themselves so deeply in my memory that they trigger feel good nostalgia.

Bad Brains’ album The Youth Are Getting Restless is the exception. Only Bad Brains expanded my mind.

Although I owned all their early studio albums in high school, this live album is the version of Bad Brains that I keep playing in mid-life. Recorded live at Amsterdam’s Paradiso Theater in 1987, The Youth Are Getting Restless includes most of their best songs performed with the precision and energy of a band at their peak. That makes it the perfect album, a live best-of that equals, and arguably transcends, any studio attempt to capture their fire. When I drive to the skate park now in my 40s, those blazing versions of “At the Movies” and “Banned in D.C” get me amped. When I’m trying to keep focused in bowls that are deeper than I’m able to safely skate, I play “The Big Takeover” and prepare myself for injury. And when I need to recover from a fall, I play the reggae as balm. The way the band mixed The Beatles’ “Day Tripper” and The Rolling Stones’ “She’s a Rainbow” into a dancehall masterpiece is pure genius.

Anything Bad Brains released before 1993 is essential, but they never sounded better than they do on this live recording. The albums’ reggae songs were the ones that let reggae penetrate my rock ’n’ roll mindset and convert me into a fan. They also transformed the idea of peace and love from laughable hippie rhetoric into a legitimate ideal that even tough posturing rockers could get behind. Bad Brains gave people like me permission to take down my adolescent armor and expose my desire for harmony and human connection. Just as HR intended, his music has taught me some of life’s greatest lessons: to love first, and to let that love extend to all of humanity. To choose peace, even when you feel anger. To live non-violently, even when your insides rage as punk speed.

Unfortunately, the world was not fully ready to receive the band’s message any more than it was ready to receive Dr. King’s message, or Shirley Chisholm’s message, or James Baldwin’s message, or Audre Lorde’s message, which is why Bad Brains’ lyrics sound like they were written yesterday about today’s plagues.

It’s too easy to only hear the fast songs, too easy to see HR hurling himself off the monitors in old live footage. Just as fans did back at Bad Brains’ legendary 1982 CBGB shows, many fans want to slam dance on-stage, to push strangers in the pit, and have their cinematic rock ’n’ roll moment flinging themselves atop people’s heads in the crowd. Even if fans love the reggae tunes, too many seem to miss that the furiously fast songs are not calls for violence; they’re the flip side of the slow songs’ coin, an expression of the human dichotomy, and a validation of the need to vent one’s anger without causing others harm. Yes, HR is screaming “We’ve got that attitude!” but he’s also screaming “We’ve got that PMA!” Screaming about unity. Screaming about peace. Smaller minds seem to perceive this combination as a contradiction, and they hear more of the Bad than the Brains. Bad Brains’ “spiritual anarchy” isn’t an oxymoron. Rather than existing in opposition, fury, love, anger, and enlightenment create a complex whole. How else could Dr. Know play guitar that fast with a smile on his face? Author F. Scott Fitzgerald said “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Bad Brains’ ability to do that — to build a band around it — isn’t always matched by their fans’ ability. Too many of us miss the message because we separate the musicians from the music.

What poet and critic Amiri Baraka wrote about jazz in his 1960 essay “Jazz and the White Critic” applies to Bad Brains now: “[T]his music cannot be completely understood (in critical terms) without some attention to the attitudes which produced it.” Baraka arguedthat that kind of listening “…strips the music too ingenuously of its social and cultural intent.” You can’t isolate Bad Brains’ sound from their Rastafarianism or their experience as Black American any more than you can understand their music by focusing on the punk and ignoring the divinity in their message.

“This is the whole thing with Rasta in our life,” HR said in a 1989 interview. “Without God, we feel we would not be able to give the people music that we have. Our spirit would be boring, dull, and it would reflect in the music.” Bad Brains are spiritual emissaries whose mission isn’t simply to push musical boundaries or put on an energetic show. It is to challenge listeners to question and examine themselves in order to evolve. That includes challenging the recreational fury of the fans who still come to shows to mosh without concern for how their flying fists and stage-diving can injure other fans. Bad Brains’ isn’t simply revolutionary music because it dissolves genre barriers. It is a music of personal revolution. “Revolution, this a revolution,” HR sang on their song “The Youth Are Getting Restless.” “You better watch out because here it come. Whether you’re white, it doesn’t matter if you’re brown. If you’re black, yellow, or red, revolution time come down.”

Bad Brains’ racial identity baffled people as much as their music does. “It’s kind of confusing them,” Jenifer told a camera crew on an upstate New York golf course. “I’m confusin’ to begin with, to be the dread out here. And then when they finally realize I’m on some rock shit, they just probably say, ‘Boy, that Darryl Jenifer’s all over the fuckin’ place.’” But it’s as simple as this: Bad Brains gives listeners a place to put their anger and the opportunity for healing. Being angry isn’t the same as being hateful or destructive. Anger is legitimate. Anger has a purpose. Centuries of oppression and violence breed righteous anger. Bad Brains’ slow songs of unity and peace aren’t attempts to silence anger or invalidate peoples’ responses to oppression and suffering. In Bad Brains’ music, peace coexists with anger. That combination was the whole point. As writer Matthew Salesses so perfectly pointed out, “…Aristotle said: that anger shows us not only that we feel we have suffered injustice, but also that we consider justice within reach.” He concludes: “Stay angry.” Anger is not the same as destruction. The path of spiritual and social progress often involves tearing things down to rebuild them, be they systems of oppression or systems within ourselves. Peaceful protesters have recently removed confederate statues in numerous U.S. states. Now officials must replace them with statues of leaders and artists of color. Bad Brains chose to process their own energy and experience through music and Rastafarianism. Rage alone was never enough for them. For the doctrine of Bad Brains, personal and social progress requires transforming that punk energy into something constructive.

As the 1980s progressed, Bad Brains’ energy had started inciting what HR perceived as violence at shows, and he struggled to reconcile the fans’ aggressive responses with his own role in inciting it. He played simultaneously in pure reggae bands, including Human Rights and Zion Train. When he seemed to realize his audience wasn’t able to reconcile these seemingly opposing impulses—or that fast rock was no longer an effective vehicle for his message—he left the band. His personality was also problematic. It caused tension. So did the idea of commercial interests in their music, and the way corporatizing their art effected its authenticity. He didn’t trust the music industry. “There are a lot of people telling you what they think you should do, and it is demanding on one’s talent and psyche and one’s lifestyle,” the Washington Post quotes H.R. as saying. “One man wants you to sound one way and another wants you to sound another way. You don’t really want to come out after a while.”

During the 1990s, HR drifted in and out of his bandmates’ lives, and in and out of homelessness, and became unreliable, even as Bad Brains’ international fan base grew. To erase any negative associations with the word ‘bad,’ HR got his band-mates to change their name to Soul Brains, though some part of this may have involved legal issues with past management. The band’s original lineup returned under their original name in 2007 and tried to give the fans the music they wanted without compromising their own beliefs. Ultimately, time has shown that the HR’s message was inseparable from his personal search for inner peace, which got wrapped up with his own struggle with mental health, and maybe the challenges of unifying so many sides of his personality and life. But his message is not the result of illness. As his Rastafarian musician Ras Michael put it, “The love, it flows over the sickness.”

And so it’s now we choose to fight

To stick up for our bloody right

The right to sing, the right to dance

The right is ours… We’ll take the chance

A peace together

A piece apart

A piece of wisdom

From our hearts

In 2016, Bad Brains was nominated for inclusion in The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. They did not make it in. “Our notoriety was achieved through a relentless quest to spread the message of PMA, peace and love to all,” Jenifer told WTOP News. “Rock Hall honors are not for Bad Brains.” But the music is for us all. Or in Dr. Know’s words: “What we do is for everybody.” My family are some of those people. My daughter, who turns three in July, knows all the band members’ names. She also sings the chorus to “I and I Rasta,” adding a banshee howl at the end for flourish. As a father, it makes me proud.

So, if you see a white sedan car driving around Portland, Oregon sporting a Bad Brains sticker, say hi. It’s the only band sticker I’ve ever put on any car I’ve owned. It’s meant to signal peace and love to everyone, even those people who remain filled with hate. For those of us pushing back against racism and violence in the small gestures that make up our daily lives, do as HR urged us: Never give in.

When I finally met HR at a show of his in April, 2022, we shook hands and I thanked him for filling my life with music, and for playing “I Luv I Jah” on this night. “I Luv I Jah” was always a personal favorite, but it was also the song I listened to on repeat during the days leading up to my Dad’s passing, so it’s been hard to listen to since—until this night.

I teared up at this HR show, singing and dancing to it in the colorful lights. HR listened as I thanked him for showing me the importance of non-violence and PMA. Grinning, he watched me behind his dark sunglasses, then he pulled my hand close to his heart and said “Thank you.” After we took a pic, I said goodbye to him with his own lyrics: “Peace and love.” That is the message: Peace and love. He stared at me smiling then held up one finger, toward the Creator.

I will always love this man.