Where Have All the Music Magazines Gone?

Inside music journalism post-2008 recession, and how media consumption in the 21st century offers a road map for the continuation of the once-robust medium.

When other writers and I get together, we sometimes mourn the state of music writing. Not its quality—the music section of any good indie bookstore offers proof of its vigor—but what seems like the reduced number of publications running longer music stories.

In the United States, music coverage now often comes in the form of “20 songs you need right now.” Websites offer features that masquerade as listicles detailing “10 reasons you should listen to so-and-so” or brief posts built around new singles, new videos, artistic feuds, and trending memes. Don’t get me wrong—I need music news, and I love a good list ranking ABBA’s 25 best songs, which is 23 more than I knew existed. I also love being whisked away in a story. Music is the thing that unites all people, and immersive music writing can provide as pleasurable an experience as an hour alone with your streaming service.

This isn’t an uncommon opinion: Many people I know enjoy reading and writing narratives about bands old and new. We love stories about memorable tours, obscure historical incidents, influential songs, personal obsessions, and overlooked music, like Julian Brimmers’s oral history of the short-lived genre Chipmunk Soul. We love career retrospectives and in-depth examinations of gender, race, culture, and our own identities as listeners; same for stories about lost albums, underappreciated musicians, and personalized political pieces like Ellen Willis’s “Beginning to See the Light,” an important dissection of feminism, fandom, and punk rock. These narratives aren’t pegged to a local show, or built around an upcoming album release or Super Bowl performance, which then highlights an increasingly relevant question: Without these news pegs, where do writers send them? For those of us who will likely never write for big slicks like The New Yorker or GQ, and who can’t just write books about the music we want, it’s very difficult to find nationally distributed magazines willing to publish unpegged longform music pieces. Many stories are important enough for us to try to tell, but American newsstands are now practically devoid of music magazines. Where did they go? Assessing the state of music writing requires a look at recent history, which can easily seduce you into discouraging nostalgia.

American music journalism started in the 1960s at the Village Voice and Crawdaddy but quickly became so popular that, in 1968, The New Yorker hired Ellen Willis as its first pop music critic. The decade saw an explosion in the genre’s exploration, thriving at newly established titles like Rolling Stone, Creem, Bomp!, and Cheetah, a proliferation which continued well into the 1970s. By the 1980s, it crossed from outlets like the original Bitch: The Woman’s Rock Mag with Bite into the mainstream at Spin, Hullabaloo, The Face, Right On!, MTV, and Black Beat, and at Option, Chunklet, Ray Gun, BAM, and The Rocket in the ’90s. While Rolling Stone first began in the attic of a printing press, nearly going bankrupt within its initial five years, music journalism proved to be extremely profitable.

You didn’t have to search long to find the zine-like Maximumrocknroll and Punk Planet, both as punk in their editorial independence as their musical tastes. If you went to Tower Records, you could pick up their free magazine Pulse!. Even the skate mag Thrasher published band profiles and music news. (One 1989 issue reported: “Rumor from Texas tells of a New Kids on the Block gig gone awry when Kerry King of Slayer threw beer on the New Kids’ lead singer. Kerry and Kid then proceeded to beat each other up while security held the other New Kids back.”) The Source and Vibe were the rap scene’s ultimate taste arbiters, and artists featured in The Source’s “Unsigned Hype” column often became some of the generation’s leading hitmakers, from Notorious BIG to Big Pun and DMX. But hip-hop magazines also featured those bubbling in the underground, rappers that received acclaim in Rap Pages, Stress, Straight No Chaser, and The Bomb Hip-Hop Magazine.

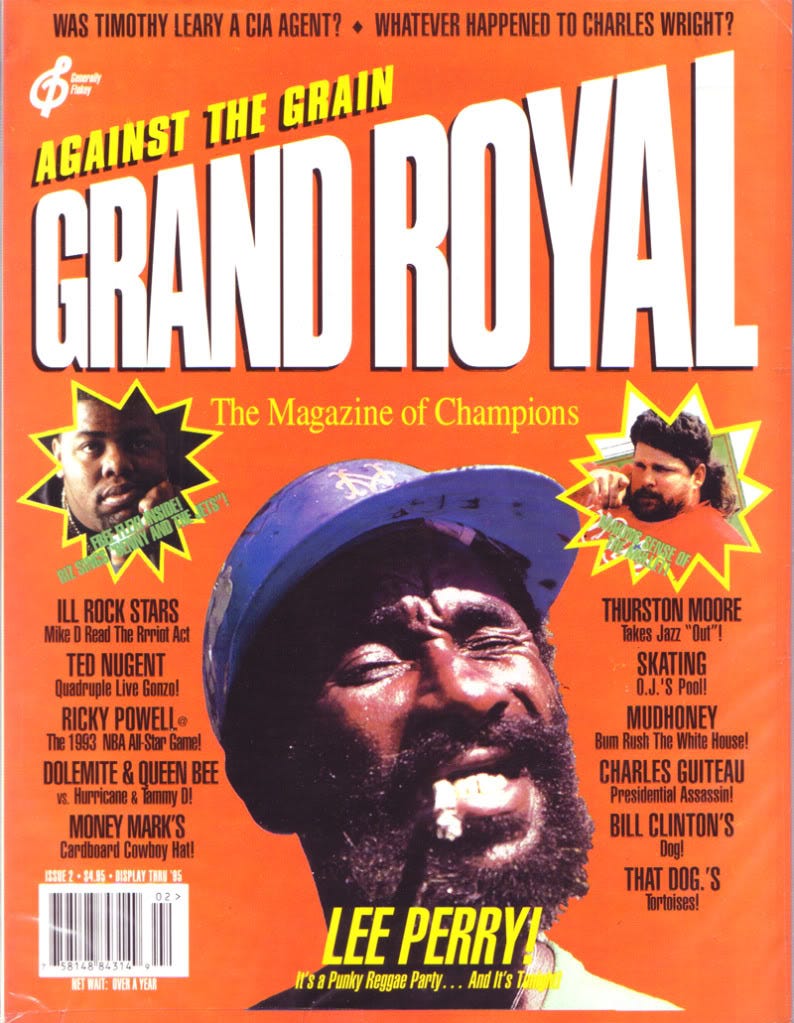

We can’t forget the Beastie Boys’ eclectic six-issue run with Grand Royal, and of course, all the fan zines across the decades, from Flipside and Forced Exposure to Chemical Imbalance. To me, this list of titles shows an unwavering appreciation for music news and stories. As one of Tower Records’ old slogans put it: “No Music, No Life.”

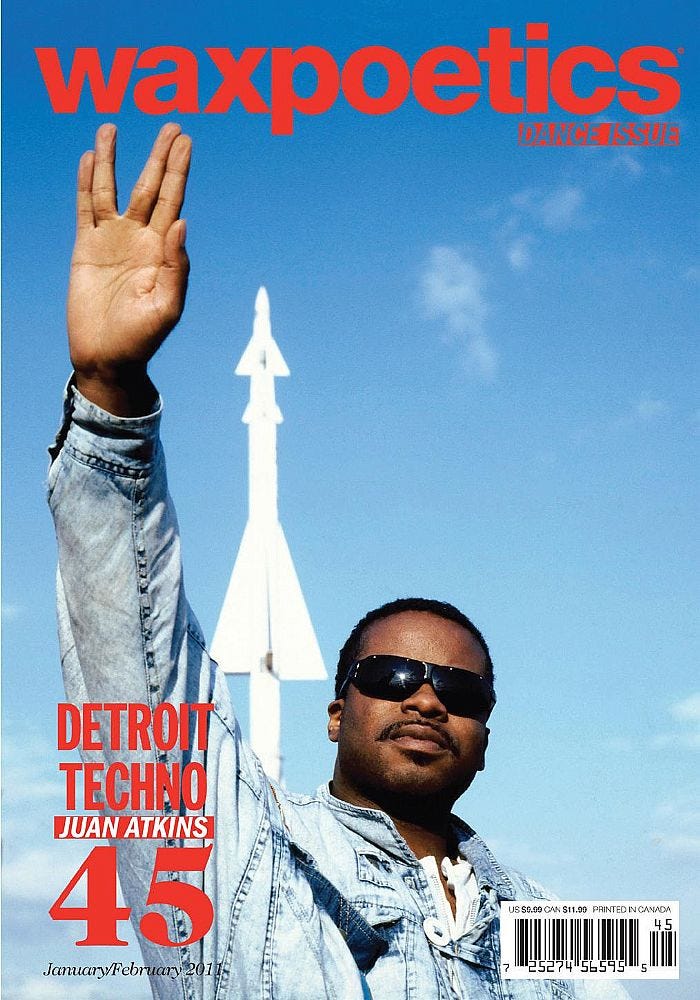

In hindsight, the 1990s and early aughts now resemble the salad days of traditional magazine publishing. It was a time when a writer like Ann Powers could reasonably hope to work as a pop music critic at the Los Angeles Times, and hip-hop journalists could launch their own print magazines like Sacha Jenkins’s ego trip. Da Capo Press’ beloved Best Music Writing anthology was an annual mainstay, and chain bookstores everywhere from Manhattan to Bakersfield stocked a wealth of glossy titles. Spin, Blender, Harp, Magnet, Paste, FILTER, The Big Takeover, Under the Radar, Alternative Press, and Rolling Stone covered rock and pop. The Source, Vibe, Wax Poetics, The Fader, Mass Appeal, XXL, and URB covered hip-hop, soul, jazz, electronic, and R&B. Decibel did metal. Relix did live, improvisational music, No Depression roots music, and Down Beat and JazzTimes sat alongside British stalwarts The Wire and NME.

Hell, there was even a magazine called Ferret Fancy—which I read! It had nothing to do with music, but its niche focus embodied these vibrant times. The quality of stories wasn’t universally high, but at least these titles formed a diverse journalistic ecosystem. Alt-weeklies like Chicago Reader, Washington City Paper, and Minnesota City Pages didn’t limit themselves to short criticism or Q&As, and they continued to publish solid music stories, while The Believer loved music so much it eventually launched an annual music issue, following the Oxford American’s lead, which had been publishing music issues with CDs since its 16th issue in 1997. The OA itself followed the lead of CMJ New Music Monthly, which was the first print pub to include a free CD. Stories from many of these publications got reprinted or noted in Best Music Writing.

And though mainstream general interest magazines like Vanity Fair and Esquire, equipped with a greater reach than music magazines, often published what seemed like PR pieces disguised as profiles, they could also surprise you. Vanity Fair contributor David Kamp wrote vividly about L.A.’s infamous Whisky A-Go-Go in 2000. Elizabeth Gilbert profiled Tom Waits for GQ in 2002. For Vibe, Karen R. Good wrote about groupies, materialism, and misogyny in hip-hop in 1999. Mary Gaitskill wrote about her complex attraction to sexist Axl Rose for Details back in 1992. I had barely learned how to pitch magazine stories by 2007, yet it was a glorious time to read and write about music. Then the 2008 recession hit.

You know the details: Residential construction ground to a halt. Manufacturing jobs got cut. Wall Street spiraled into chaos, and Main Street footed the bill. Amid the financial carnage, magazine advertising revenues plummeted. Total ad pages dropped from 255,667 in 2007 to 172,240 by 2010. Magazine newsstand sales had been declining before the recession, but magazines’ advertising revenues precipitously fell from $13.9 billion in 2008 to $10 billion in 2009, in part because online ad revenue kept cutting into print revenue—31 percent from 22.3 million in 2002 to 15.4 million in 2008. Ad sales in U.S. national magazines fell over 20 percent compared to the previous year during the first quarter of 2009 alone. When advertising shrunk, magazine budgets shrunk. Once reliable publications like Rolling Stone cut back their page numbers, not to mention dimensions. Others like Harp and Blender flat out died. To streamline operations, magazines restructured sales departments and reduced print schedules and staff. Vibe briefly shuttered in 2009, then resumed publishing just six issues a year. Others, like URB, converted from a print to an online magazine. Paste traded print for web in 2010 in an effort to stave off its demise, but only after first installing a failed pay-what-you-wish subscription system modeled after the one Radiohead used for its 2007 album In Rainbows. Spin stayed with its print model until 2012, the year Spin Media’s new CEO laid off 11 editorial staffers and reframed the magazine as “a media company with a print property,” further distancing themselves from print journalism. When the recession’s dust settled, after a period of almost two years, newsstands looked very different, and that’s largely how they’ve remained.

Magazines rise and fall. They lose relevance, their founders move on, or get revamped or shut down by new owners. Some speak for their generation, then the next generation finds a way to speak for themselves. The internet has shaped how current generations speak about music.

Before the internet, when people bought records, tapes, and CDs, they found new music from professional music critics, record store clerks, MTV, and word of mouth. This meant that record labels needed magazines to advertise their newest offerings. Labels hung big promotional posters in record stores, and chains like Tower and Virgin had sizeable magazines racks. As music critic Simon Reynolds described that era: “All music and most information were things you literally got your hands on: they came only an analogue form, as tangible objects like records or magazines.” If you wanted to discover records by the loud scuzzy garage bands that mainstream media ignored, like Nights and Days, you read a zine like Jay Hinman’s Superdope. If you wanted to know if the mainstream albums that just came out were good, you read Option, which ran hundreds of reviews. One 1988 issue I have contains 37 pages of album reviews, five pages dedicated to cassette reviews, and a six-page ad from SST records! “The net destroyed the model,” editor Jack Rabid told me via email.

Rabid has run his rock magazine The Big Takeover since 1980, and he believes the mainstream adoption of the internet in the mid 1990s irrevocably changed our listening habits. Instead of buying albums, we could listen to songs online and download them on file-sharing sites. It was fantastic, but it also crippled the music industry: Album sales declined and record label budgets plummeted, which meant they had less to spend on print ads for promotion. The listening public quickly got used to getting music and news for free, and many became less willing to regularly pay for things. As Justin Timberlake’s Sean Parker remarked in The Social Network upon being told the record companies defeated Napster in court, “You want to buy a Tower Records?”

“Because the more content that could be accessed for free on the net,” Rabid told me, “the less people were willing to keep buying physical mags as they had in the past, no matter how good. And that not only hurt mags; most of all, it hurt the stores we counted on to sell us, especially the sort of indie book and record stores and magazine racks all over the country that went out of business the last 20 years. That was our other lifeblood and it’s nearly all gone now. We lost half our sales over the last 15–20 years to such closings, half of them to Tower, Virgin, Hastings, etcetera, and most of all Borders, but the other half to little mom and pop concerns that were the lifeblood of their communities and offered something more tangible culturally and socially than the more passive net.” He called it “an endless loop of deterioration of the funding and structure.”

To freelance journalist Annie Zaleski, the hyperabundance of digital entertainment has lessened music’s popularity and cut into magazine readership. Even though Zaleski, who has contributed to Billboard and Rolling Stone, subscribes to the print editions of Entertainment Weekly and Guitar World, she sees music playing less of a role in people’s lives. “There is simply so much media competing with music,” she says. “TV, movies, video games, even social media itself—that music isn’t as central to the lives of many people, so it follows that there are fewer music-only publications. People’s cultural consumption habits tend to be broader today, simply because there is so much great, creative art to seek out and enjoy—and so much of this art is available online and accessible to more people.”

The internet freed information from specialists. Why do you need a magazine to tell you what Wikipedia and blogs can for free? “An interview with your favorite artist used to be sacred but now it’s mundane,” Brian DiGenti, the cofounder of Wax Poetics, told me. “The idea of people being excited about finding out the tracklist of an upcoming album is now absurd. As is waiting months for a new album to drop.”

Amy Linden, who wrote prolifically about hip-hop during the ’90s, recognized similar issues with readers’ desires and attention spans. “I don’t think people are curious they way that they used to be,” Linden told Pitchfork in an epic piece about hip-hop journalism. “How can we expect thoughtfulness when we’re interested in hashtags and tweets and fast thoughts?”

Some of those I spoke with for this piece, like DiGenti, also believe digital natives read less in general. Caryn Rose writes extensively about music, but she’s also beholden to new music journalism, having recently published a thrillingly exhaustive “All 218 U2 Songs, Ranked From Worst to Best” at Vulture. “The challenge is that while more people than ever listen to popular music, its ubiquity means that less people than ever want to do the deep dive.” Back in the analogue era, acquiring information and music required effort. You had to visit record stores to hunt for it or ask your cool older sister for recommendations, fleeing when she caught you pillaging her record collection while she was in the shower. “We didn’t really need gatekeepers anymore,” Amos Barshad wrote in Slate. “The monoculture weakened; a million little tribes sprung up in its place. How could any one person claim a universal authority over all of that?”

Back when we needed specialists, music magazines provided part of readers’ identities. We find our people and identify with a group, and music provides a particular plumage to advertise our tastes and tribal affiliation—be it punk or pop or hip-hop. When you’re young, you need to be in the know to earn cred. Jonah Weiner captured this well: “Picture that mythical orange-haired girl walking around a nowheresville suburb in 1994 with a rolled-up Spin in her back pocket—it’s not just a magazine but a badge, an amulet, a pipeline to a world far removed from her local food court.” Journalist and Longreads editor Danielle Jackson was one of those teenagers.

“For a long time I decorated my walls with different artists pulled from the magazines,” Jackson recalled, “like Word Up! and Right On!. Then in high school I had a group of girlfriends who were all very invested in what was happening in music at the time, and we wrote and performed poetry different places. It was a thing in the mid ’90s, and it was bad stuff. When a new Vibe came out, we’d have sleepovers or these long phone calls to dissect pieces and turn around the arguments with each other. It was nurturing to be around other people who took art, music and writing seriously, and the writers we read taught us that we weren’t weird to care so much.” This intense relationship with the printed word helped cultivate her affinity for pop culture and stories, which proved essential to how she built her career into the kind of journalist and cultural critic she once read as a teen.

Online chat rooms, Twitter, Facebook, and blogs reduced the role magazines played in exchanging information and constructing identities. As Weiner wrote in 2009, “Music magazines were an early version of social networking. But now there’s this thing called ‘social networking.’”

“Pop music used to be something people had to seek out: Find the right FM station, watch [the TV variety show] Midnight Special late at night, drive to a venue and buy a concert ticket,” former Blender music editor and Rolling Stone contributing editor Rob Tannenbaum told me by email. “Now, music is everywhere. It’s mobile, it’s accessible, it’s ever-present, it’s playing at Walgreens. It’s possible we’re so full of music, and surrounded by it so continuously, that we take it for granted. Music is air. Reading a music magazine, at this point, might be like reading about air, and no one would do that.”

But even for those of us who still liked reading about air, reading habits have changed, and print struggled to compete with expanding online coverage.

Access to personal computers became more common in the early 1990s, and people began reading more online. Some magazines were quick to transition. Ex–Rolling Stone staffer Michael Goldberg capitalized on this shift by launching the first online multimedia music magazine Addicted to Noise in his bedroom in 1994. “Rock journalism had just dried up,” the forward-thinking Goldberg told MTV News. “Most of the stuff was professional but soulless. Reviews had become consumer reports. Interviews that got the artist to open up and talk about their work and what they were trying to do and what it was about just weren’t there. … I also felt like a whole piece of rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t being documented—the kind of music that is eccentric, underground or overground, but has a spirit in it. I wanted that.” ATN went deep, and was a harbinger—by the time it folded in 2000, others had started experimenting with digital publishing to create the sorts of websites they wanted to read and to capture the readership that was migrating online. One such adopter was Ryan Schreiber, a recent high school graduate who founded Pitchfork in 1996 as a music news and reviews site. Another was Sara Zupko founded PopMatters in 1999 to cover all forms of culture.

But by the Great Recession, many web-savvy tastemakers had expanded upon the medium, launching music blogs—aka audioblogs or mp3 blogs—like Fluxblog, Stereogum, Aquarium Drunkard, Brooklyn Vegan, Gorilla vs. Bear, and Tiny Mix Tapes. Bloggers could respond to breaking news and post reviews more quickly than print journalists. Rather than a business, this was often pleasure; many blogs eschewed advertising completely, and the model was dependent on creating communities explicitly through sharing favorite songs. Besides a new publishing model, one unique thing blogs offered was music itself.

Sites like Aquarium Drunkard could post rare live recordings that bands hadn’t released, creating niches even more unique than rock or rap magazines. The web specializes in immediacy, and with fewer print publications to promote bands’ music, publicists sent music bloggers songs to share, making some blogs so popular that a posted song functioned the way a band’s single had in previous decades. Blogs’ curation served listeners the way record stores once did. The internet had become, as Nick Hornby put it, “one giant independent record shop.” Most blogs were for music, though, not for longform music writing.

The internet created a frontier where consumer desires were no longer clear. Did people want stories anymore or just brief posts? Did they want playlists instead of album reviews?

As reading habits changed during the early 2000s, the issue of what exactly people will pay for emerged. So did the issue of how we read online, for free or not. Theorists feared technology had ruined us. Some cultural critics diagnosed us all with ADHD, no longer able to focus on stories. The generalization was unfair: The way we consume and digest information in print differs greatly from the way we do online, and that affected music magazines’ performance. Simon Reynolds, who grew up reading England’s music weeklies like NME and Melody Maker, articulated the different reading experiences perfectly: “Concentration of a different kind was involved in reading the frequently very long features. It’s perfectly possible, of course, to flick desultorily through a printed magazine in just the same way one drifts shiftlessly across the infosphere. But something about the bound nature of the magazine encourages getting pulled into a story, and staying with it until the end.”

This isn’t to say the past was some high point in music literature. I reread a bunch of long stories from CMJ New Music Monthly, Option, Spin, Under the Radar, and DownBeat. I found lots of amateurish sentences, bland takes, adolescent humor, insider jargon, and writers rehashing the narrative that publicists sent. I did find some jewels: Eve Babitz on the death of Gram Parsons; Gina Arnold on Nirvana in 1991, right before they broke; Mark Kemp on Meat Puppets in 1995. But just like today, story quality varied. Sure, there were more of them, but the fluff was abundant.

So then what is the function of a music magazine now? Album reviews? Profiles or best-of lists? “I think many companies are still trying to figure this out,” DiGenti told me.

“I’d like to believe that people still want what music magazines provided best,” Rose said, “which was providing more information through which you could appreciate a band or a song or a record.”

One thing that the internet hasn’t erased are album reviews. As evidenced by Pitchfork’s growth since the site launched in 1996, people still seek music critics’ guidance. Following the site’s debut, when it was known as Turntable, readers came to expect articulate and compelling album reviews and insightful monthly interviews. Schreiber’s background spoke to the music journalism ethos established by Paul Williams, Jann Wenner, and others: in his late teens, Schreiber was doubly influenced by zines and the musical history of his native Minneapolis. Upon moving to Chicago, Pitchfork expanded into a hub of daily music news and album reviews, focusing on indie and underground music; while the writing was occasionally snarky, it’s decisive tone and cutting edge taste helped establish Pitchfork as the internet’s most influential source of music criticism. Eventually, the site began publishing in-depth features like Aaron Leitko’s 2012 profile of the tireless Ty Segall. I read music magazines for lively stories like Leitko’s, and Pitchfork amplified the reading experience by floating images and text on top of each other using parallax scrolling, something magazines could only do online.

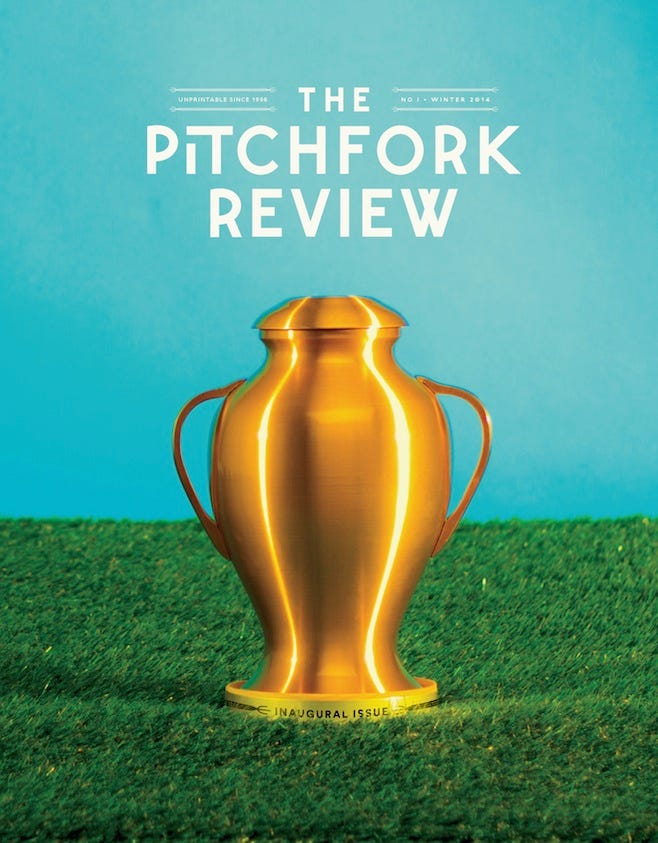

In the fall of 2013, the site further tested the limits of longform and launched a quarterly magazine called The Pitchfork Review. Despite the challenges of print journalism, it was an ambitious experiment—one website referred to the quarterly as “New Yorker meets Paris Review meets Adbusters.” Newsstand copies cost $19.96—a nod to the year of Pitchfork’s founding—and focused on long stories about everything from Otis Redding to English music weeklies to the history of the jukebox.

It was a bold move, but the Review wasn’t recreating early music magazines. It was tweaking the model to see what it could still do, and to gauge if readers wanted the journalistic equivalent of slow food in a fast-paced era. The site handled breaking news and first takes, while print shined through the thoughtful handling of stories like a profile of Kansas’ infamous DIY venue, The Outhouse. In Issue 2, editor J.C. Gabel clarified the magazine’s mission: “We love the speed and community of the internet, but there’s so much noise (and far too few filters) that important stories can get lost.”

By Issue 5, the Review had hired its first official editor in chief—Jessica Hopper, who had previously been a staff editor. The move was insightful: Hopper started her own music zine, Hit It Or Quit It, at age 15, only to begin freelancing for an alt-weekly a year later. She then launched a PR company around the time Pitchfork debuted, representing both bands and labels, so when she was hired as EIC, Hopper was one of the most visible, versatile, and dynamic music journalists working.

For the Review, she said she planned to publish “stuff that’s not even doable anymore because it doesn’t fit into people’s verticals,” like a 20,000-word oral history of the band Jawbreaker, as well as “longer pieces on contemporary artists that we think are going to be canonical.” She wanted it to be “the kind of magazine where you pull it off the shelf in 10 years and you know who everybody is.”

When I visited Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, in July 2018, the rack had 14 music magazines. Of course Rolling Stone was there, now under new ownership for the first time since its 1967 founding, but most titles at the world’s largest new and used bookstore targeted working musicians and industry professionals rather than the curious listener: Guitar World, Fretboard Journal, DRUM!, Sound on Sound, Future Music, American Songwriter, and Tape Op. It was weird. DownBeat stood near JazzTimes, both as thin as tourist brochures. For a splash of rock and pop culture, it had Maximumrocknroll, The FADER, and The Big Takeover. By chance, The Believer had just released its newest Music Issue. It included one of the best pieces of music writing I’d seen all year: Steve Silberman’s essay about jazz pianist Bill Evans’s enormous and tragic talent.

Sadly, The Pitchfork Review was no longer among them. It folded in 2016, after just 11 issues. The Review wasn’t a failure. Just as Pitchfork had proven that some people still wanted album reviews, their print experiment confirmed that a handful of hardcore folks still wanted to read about music in a beautiful literary object, just maybe not enough of us to keep that object alive.

“I really miss doing the Review,” Hopper told me, “making a thing with the cool cabal of those three women (and my longtime collaborator Michael Catano). It was hard, but not for any of the typical reasons. I do not know why it folded, that was after my time, but I think about it a few times a month, and at events I hear from people who loved it or found it educational or meaningful. That’s what mattered most to me, it being a seed, rather than an institution.”

The Pitchfork Review believed that print music journalism wasn’t dead; it just needed to adapt to the times. What Tower Records’ old slogan said is still true: “No Music, No Life.” We still have music, and listeners didn’t lose our lives when magazines lost theirs. Music journalism survived by becoming niche, and by focusing its coverage, deepening our listening experience, and broadening our musical tastes. And as much as the internet has affixed media’s attachment to the news cycle, it has also allowed niche publications to detach themselves from that cycle, and rather focus on creating stories that are evergreen, stories whose subjects and themes exist, like the internet itself, in a realm beyond the bounds of time. They can just tell good stories.

In a 2009 piece for Slate, Weiner points out another reason music writing often fails to engage a large general audience. “Many readers who are otherwise passionate about culture have little time for music writing, irritated that it speaks in abstract, jargon-stuffed language about ostensibly mainstream entertainment,” he wrote. “Music writers are charged with describing more ineffable things, and the frequent result is a pile-up of slang and shorthand references, purplish gushing, and tedious emphasis on lyrics.” As a consumer and creator of music writing, that’s expressly what I liked about the Review’s experiment, which wasn’t bound by an outdated subset of rules. It could be inventive in its voice and with a range of musical styles and approaches it chose to cover.

When writers focus on musicians or their lives as listeners, they focus on the people who make or consume music, on the music’s historical context, its time and place, rather than on dissecting the music itself. That brings the abstract out of the abstract. By transporting characters and scenes in a concrete recognizable world, music stories draw readers into a narrative that appeals to a broader audience, one capable of reaching beyond the small cadre of hardcore music fans who speak jargon. Then we can think of music stories as another form of compelling entertainment—not necessarily music journalism, but good storytelling. That’s what the films 20 Feet from Stardom, The Last Waltz, Searching for Sugarman, and Stretch and Bobbito are: masterful, popular, human stories about people that also involve music. That’s also what the internet can do for music journalism—stories like J.P. Robinson’s incredibly original, absorbing feature about the mysterious hippie William Jellett, who danced for decades at countless rock shows in the U.K.

Or that Red Bull’s sponsored online magazine has published some of the best online features about hip-hop, beats, and pop music around. During the past two years, British producer Kirk Degiorgio wrote about “The Roots of Dub,” and Benjamin Meadows-Ingram wrote about the way the Showboys’ 1986 song “Drag Rap” shaped Southern rap. But what’s fascinating about the funding from a lucrative global beverage company is the absence of #sponcon.

The Powell’s newsstand’s biggest surprise was Ugly Things, a 35-year-old magazine dedicated to ’60s and ’70s rock, garage, and psyche, what it calls “Wild Sounds from Past Dimensions.” Born in England, Mike Stax started Ugly Things as a fanzine in San Diego in 1980, using, in his words, “an electric typewriter, Letraset, scissors, and glue.” It now prints 5,000 copies of each issue. (For comparison, Rolling Stone had a total circulation of roughly 1.5 million.) Ugly Things has endured partially because of its specialty. Nearly four decades of passionate examination of one musical niche has created a devoted readership. Second, it caters to a subset of readers who want long, thoughtful stories they can touch and return to. This type of reading appeals to people who enjoy listening to records: It’s tactile, slow, has arguably greater fidelity.

“It’s like the difference between listening to music on vinyl verses streaming it online or downloading an mp3,” Stax told me. “Part of it is the possession of a physical artifact, a tactile embodiment of the work that went into its creation—the cover art, the layout, even the ads, are all part of it, and all help provide a personal connection between reader and writer. In the case of Ugly Things, it’s something our readers want to hold onto, keep on a bookshelf, and return to again and again.” Stax recognizes the unique advantages of online publishing, but he committed himself to offering a reading experience that the web cannot. “That is where I see print’s most important role. We can publish the kind of lengthy, deeply researched stories that you can’t find online. Storytelling is a huge part of what Ugly Things is all about. Our stories range from two or three thousand words up to thirty or forty thousand words. We’ve even serialized stories of up to one hundred thousand words. Some of these stories take years of research and detective work. You won’t find that kind of music writing anywhere online.” Jack Rabid at The Big Takeover has a similar perspective, explaining that the magazine’s survival depends on investing “a lot of thought, knowledge, experience and taste into something built to last longer and dig deeper.”

He continues, “My proviso is that I never let our print content appear on the net, not only because I have never bought into the fallacious model that people will pay for what they can easily get for free, but also because I feel like people experience arguments and writing differently when they read it on a page than on a screen.”

In a sense, digitization has made print media not only quaint, but a prestige item. As the world around both Ugly Things and The Big Takeover changed, it reframed their offering as a distinct art form enriched by an aura of vintageness, even craftsmanship, a rock ‘n’ roll version of small-batch coffee or hand-churned butter, one that particular people seek out since it’s no longer the default of day-to-day life. I like that about them, but I’m biased.

Billboard and the redesigned Rolling Stone have since taken a similar approach to The Pitchfork Review, making themselves into collector’s items. Billboard prints its issues on thick, glossy stock to give them staying power and the sort of tactile, collectible appeal of vinyl records. “The issues are more like keepsakes,” Zaleski says, “like a book you’d display on a coffee table or shelf.” As one grave New York Times article put it, print magazines “might eventually gain a cult following akin to the interest around other obsolete media, like vinyl records.” “Eventually, they’ll become like sailboats,” former New York magazine editor Kurt Andersen told the Times. “They don’t need to exist anymore. But people will still love them, and make them and buy them.”

Those are the people DiGenti wants his magazine to appeal to. “My goal is to return Wax Poetics to its roots,” he told me, “where we again are a collectible journal—more like a book—something that’s fun to flip through.”

And while collectability isn’t a new strategy—Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair have employed this business model for years with special issues that target baby boomer nostalgia by putting vintage bands, like The Who and the Beatles, on the cover over and over again—the print reading experience is different enough from the online experience that people seek it out.

Aquarium Drunkard contributor Tyler Wilcox likes the way British print magazines mix old and new music with bold design and offer a way to consume information privately. “The physical, tactile experience is still important to me,” he said. “There’s also just a (primal? paranoid?) need to be offline from time to time that keeps me reading them. There’s nothing ‘tracking’ me when I’m flipping The Wire, it’s more of a private experience. Sites like Aquarium Drunkard I see as an evolution of the zine culture of the ’80s and ’90s—niche, free-form, immediate, low-key.”

In an era where people just stream—and don’t own—music, collectible magazines may seem anachronistic, regardless of production values and subject matter. Ultimately, these publications endure because of their enduring, universal subject. “Music is something found in every country in the world,” said Rabid. “People need music; people make music, always have. It’s how we feel alive. It’s no secret that when people are happiest, like when they fall in love and it first hits them, they sing little songs to themselves, and music speaks to them the most… I sing to myself all the time. I know I am not alone.”

In New York in 2001, DiGenti cofounded Wax Poetics. A friend had recognized that no magazines covered the culture of crate-digging, in which collectors search for old records to sample beats. As Andre Torres, DiGenti’s partner, told one interviewer, “No one was even touching jazz, soul, funk, or anything like that.” Wax Poeticsreimagined music journalism by connecting vintage and contemporary jazz, soul, reggae, and hip-hop, carving a niche that showed the ingenious ways present-day musicians used vintage music to create a completely new art form.

“It’s like a time machine. You use hip-hop to travel back and pick up on everything that’s happened before,” Torres told Current TV. Wax Poetics was also designed like a book: to last. “I wanted to create something that, when you finished reading it, there would be no way that you would ever think about putting it in the trash.”

Their formula worked. “People held onto them as research material. Kept them in crates next to their records,” DiGenti told me. “We were either too obscure or too smart for the masses. But we thrived within our niche. And we had the music industry on our side. Our buzz was always hot because musicians, producers, DJs, and labels loved us. Even other magazines respected us.”

T: The New York Times Style Magazine called Wax Poetics “the best and most exquisitely laid-out music bimonthly in America.” They published anthologies, released records, and introduced readers to classics through each issue’s regular “re:Discovery” feature. But in 2016, Torres left to work at Universal Music Enterprises. “Hip-hop is now 40 years old,” he told Billboard. “With that data, we can clearly see there’s a group of fans out there who have been underserved out there. There is a desire for deluxe packaging, creative marketing campaigns around catalog.” The magazine hasn’t fared well since his departure.

In early 2018, Wax Poetics subscribers received a terse email: “After sixteen years in print, we will cease being a traditional newsstand publication.” The email detailed how financial issues forced the magazine to restructure and relaunch with print-on-demand issues. They apologized that they couldn’t fulfill existing subscriptions, but they promised what other music magazines had before: that their new business model would let them to stay committed to in-depth music writing.

Maybe in the end, most music publications are ephemeral expressions of their time and place, rather than fixtures. Maybe it’s best that music magazines be like the timeless musicians they cover: bright, brilliant flashes that grace the earth for only a brief amount of time rather than overstay their welcome, more Iguanas and MC5 than The Rolling Stones.

In 2008, music blogger Jace Clayton spoke with The Guardian about early mp3 blogs. He created one titled Mudd Up!, where he covered music and other topics, including his own recordings. What he said remains relevant a decade later: “Maybe the album is dead, but people love songs more than ever and hold them closer to their heart. That’s what makes this pursuit seem worthwhile.” The same is true of music writing. The print magazine might be dead, but music journalism is continually evolving, impacting listeners on various levels. People will always hold music and stories close to their hearts, which makes storytelling eternally relevant, no matter the medium. But before music writing can thrive, music must be valued, not just heard. Jason Pierce, of Spacemen 3, put it well: “I mean, now we can download the whole Neu! or Steve Reich catalogue immediately. People can have their lives stuffed with music, but that’s not the same as it knocking you sideways and becoming part of who you are.”

This story originally appeared at Longreads in 2018. Matt Giles edited it, Ethan Chiel fact-checked, and Jacob Gross copy edited it. And Katie Kosma created the original header artwork for it!

Intellectually, I know the problem is structural economic issues. I guess I just feel like the unconditional victory of poptimism, its takeover of essentially the entire industry as the dominant paradigm, left all of the publications out there sounding exactly the same. How many times can you read the same piece about how Taylor Swift is the greatest musical genius since Beethoven?

This is so good. Aaron, thanks for writing it.