Chokin’ on a Breath Mint: The Sound of Early Beck

Celebrating Beck's weird youthful lyrics, a breath of fresh air in the serious grunge '90s

Nirvana: Our lyrics make no sense

Beck: Hold my beefcake pantyhose

—YouTube commenter

Twenty-seven years after first falling hard for Beck’s “Loser” as a stoned, thrift-store-shopping college freshman, I played Beck’s 2005 album Guero for my three-year-old daughter, Vivian. I’d found the CD in a box in our basement, and I brought it on a whim to pick her up from daycare. That afternoon, we sat in our parked station wagon, she in the passenger seat eating soba noodles for snack, me in the driver’s seat, and we played each song in our parked car.

“What’s that sound?” Vivian repeatedly asked as things bleeped and blooped. “What’s he saying?”

“Well,” I said, “it’s complicated.” How do you explain “Perfunctory idols rewriting their bibles” to someone who’s the Muppet Babies’ target demographic? Something about metaphor, rhyming, and playful word salad? Whatever the lyrics’ meaning, she quickly learned some of them, rattling off lines in a semi-accurate pantomime, like people do basic Japanese phrases while traveling abroad: Black hearts in effigy. Irashaimase. The way she could recite gibberish without knowing its meaning reminded me of Beck’s lyric “Karaoke / Vomiting morons,” which reminded me how much I used to love Beck’s early lyrics for that exact reason: He treated language as an instrument whose pleasures lay beyond meaning.

Playing Guero for Vivian made me dig Odelay out of the basement the next day. This was the same CD I’d had since the album came out in 1996. The broken lid slid off the jewel case, and the scuffed disc fell out. When I found myself jamming “Hotwax” and “Minus” on the drive to and from school, I jammed Mellow Gold at home, too, and Stereopathetic Soulmanure, and various singles. “SA-5,” “Motherfucker,” the dark jangly “Erase the Sun,” the discordant “Lemonade,” the fuzz-pop “Electric Music and the Summer People”—damn, I’d loved these songs. There was the music, and there were those lyrics.

“Tell me where you want me to go / If I’m gone, then I’ll get there soon.” And: “Waking up delicious ghosts / They’ll eat themselves from coast to coast / Dancing in their bandages / The victims grow, leaving messages.” And who can forget: “Chain smoke Kansas flashdance asspants.” Twenty-five years after memorizing it, that line still cracked me up. If the road-weary, heartbroken Beck of Sea Change who sings “This town is crazy / Nobody cares” is the one I love now, it was that surrealist “Bogusflow” Beck who first won me over, singing “Like a force field of multiplying meat / Cut a hole in the floor to see / How close to hell we’re standin’.”

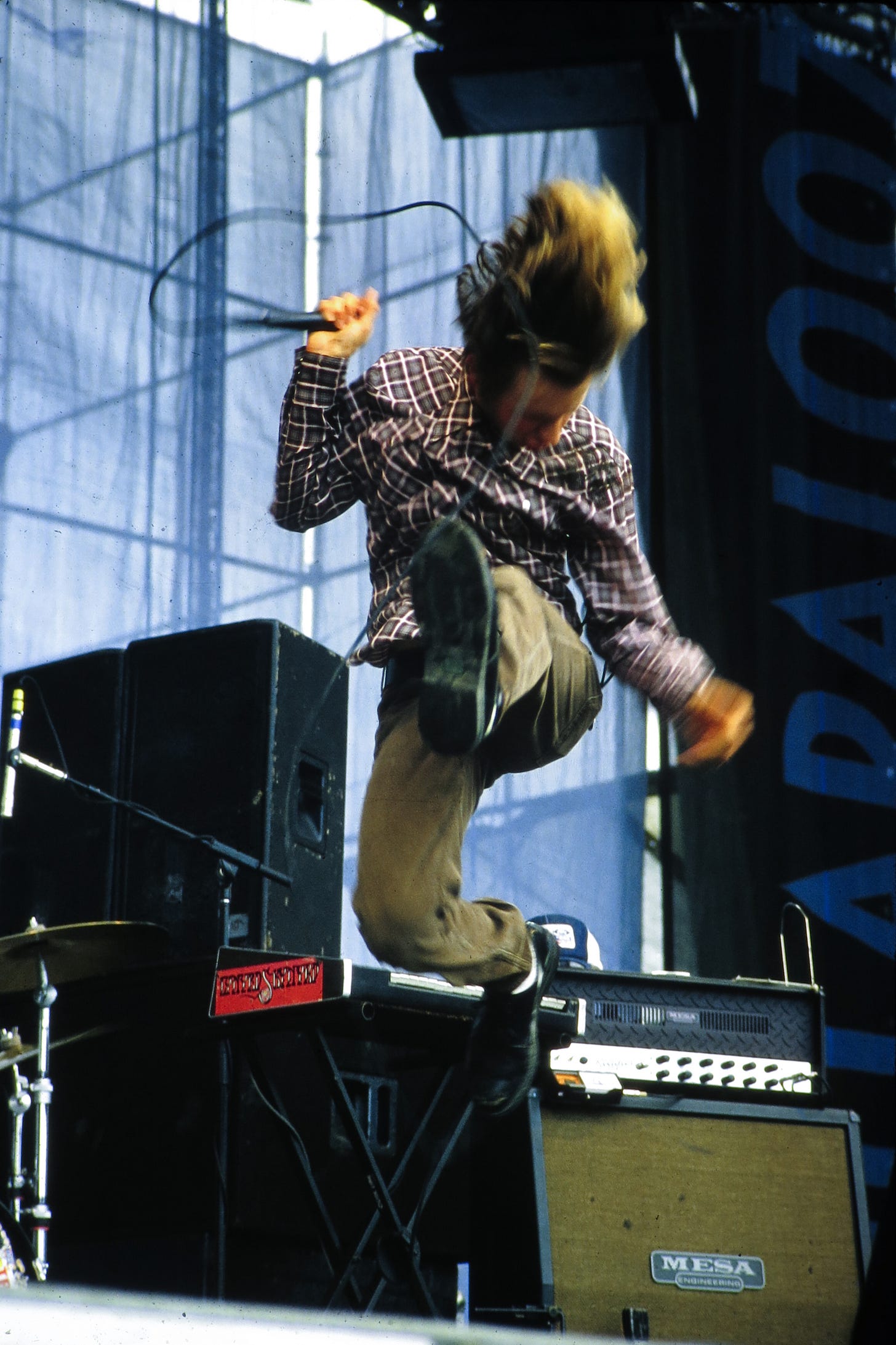

Like many ’90s kids, I discovered Beck when “Loser” hit it big in 1994, and I immediately gravitated to his lunatic aesthetic. He sang in my vernacular, about tacos, malt liquor, and the devil. He thought Ozzy was as comical as I did, telling a coffee shop crowd “Ozzy, you’re the man / How can I grasp your power? There’s mascara bleeding out of your eyes.” Videos and photos showed young Beck perpetually in motion: swinging things; smashing things; breakdancing; laying on the ground beside beer cans and an axe; running a flaming squeegee across a windshield; answering an unplugged phone during an MTV interview, only to smash it on the ground; holding a pitchfork while wearing goggles that made him look like a giant insect in a flannel. Basically, he looked like me and my spastic friends, except with musical talent. Watching him was like discovering an entire universe where people spoke their own language and had their own codes, so seeing him drag a coffin through the woods in the “Loser” video made it seem like it wasn’t a video at all, just a documentary of his daily life. Beck confirmed my hunch that the world was filled with many strange parallel universes that existed right beside your own, and that, if you were lucky, you occasionally stumbled into them. Now could we create our own?

“Loser” led me to his full-length debut Mellow Gold. After that, I bought everything I could find, from the Stereopathetic Soulmanure CD to the A Western Harvest at Midnight 10-inch in 1995. When Odelay shot into the mainstream in 1996, I listened to that and every new single constantly. I stayed devoted through Mutations, Sea Change, Modern Guilt, The Information, all the way to Colors in 2017. My wife and I still listen to Sea Change, and we saw Beck play on his 2015 Morning Phase tour. Band members’ kids came on stage, dancing and handing the bassist his instrument. It was adorable. But I lived my 20s to the Beck who sang “Unglued, depressed / The meatloaf in my chest,” as he browsed through Modesto, a “supermarket town” where “the girls don’t talk when I’m around.” Until that day with Vivian, I hadn’t listened to early ’90s favorites like that in ages.

Pawing through my box of old bootlegs, I laughed at all the memorable titles that decorated Beck releases: “Corvette Bummer,” “Aphid Manure Heist,” “New Age Blowjob,” “Cyanide Breath Mint.” Titles like “Steve Nicks Licked Me” told a warped story, as did the refreshingly literal “Today Has Been a Fucked-Up Day.” The words sent me through a wormhole back to my youth. I was excited to listen but unsure if Beck’s adolescent lyrics would appeal to the 45-year-old father version of me the way they did the college kid version. Beck laughs while singing “California white boy sound” on “Bogusflow,” but would I? To my relief, I did. “Rocket powered and nailed to the ground,” I sang as I had in ’95. Like Beck, I had changed, but my sense of humor hadn’t matured as much as I liked to think.

Somehow, Beck’s old stuff held up. No matter how many times you’ve heard “Loser,” and how fucking sick of it you got, the lyrics are brilliant fun that sound as fresh in 2021 as they did in 1994 when many of us were the “losers at the cruise control.” “’Cause one’s got a weasel and the other’s got a flag / One’s on the pole, shove the other in a bag / With the rerun shows and the cocaine nose-job / The daytime crap of the folksinger slob / He hung himself with a guitar string / Slab of turkey neck and it’s hangin’ from a pigeon wing.” Each line is its own comic universe. Together, they create a cosmos. So many Beck songs are like that. Killer Beck lines are a dime a dozen. It’s hard to believe anyone dismissed him as a one-hit wonder.

Back then, he excelled at putting unlikely words together to see how they behaved as strange bed fellows. Collage is a very youthful activity. You hear a lot of cut-and-paste in student poetry. You can buy refrigerator magnets to perform the same experiments in your kitchen. Naturally, many of Beck’s juxtapositions read as nonsense, but the comedy of nonsense was much of their appeal, and his fearless experimentation is exactly the spirit young people need to help set them free.

“Don’t believe everything that you breathe / You get a parking violation and a maggot on your sleeve” set the standard of lyrical collage. And he followed “Loser” with countless lines that set a new high-water mark for weirdness. In “Minus” he sings: “The janitor vandals they bark in your face / Juveniles with the piles and paste.” In “New Pollution” he sings: “She’s got cigarette on each arm / She’s got the lily-white cavity crazes / She’s got a carburetor tied to the moon / Pink eyes looking to the fruit of the ages.” For years I thought he sang “cigarette army charm.” It didn’t matter. Beck made that kind of stuff up on the spot. “Most of the vocals on the record [Odelay] were scratch vocals,” he told Rolling Stone. “We just grew attached to them.” He’d spit out lyrics after recording the music during Odelay’s initial recording, and instead of replacing the draft, place-holder lyrics, he kept many of them, because his improv generated some unusual stuff. It often had.

I did a lot of drugs in the ’90s. Anything weird appealed. Unfortunately, drugs didn’t make Beck’s lyrics make sense. Sense wasn’t the point. The words sound great together, and sometimes, in the process, they painted a picture or suggested a deeper meaning. Early on, words seemed to primarily be another instrument for Beck, less a source of meaning than another source of sounds. He always played with their sounds, stretching, twisting, squeezing, and warping them. He chose words that were as funny to hear as to say: slab, neck, mangle, bucket, and strike. Saying them out loud was the point. They weren’t meant to be printed in a book to read as poetry. They weren’t their best selves recited in silence in your head. You had to say them. Feel them in your mouth. Roll your tongue over their contours, elongating the vowels and hammering the consonants, bouncing their syllables with some put-on twang. Beck is a sampler. Listen to Odelay. He’s a DJ collagist trash compactor. He mixes things together, from his own instruments to samples from songs, movies, field recordings, and ambient noises. Lyrics are just one more sonic thread in a song’s tapestry. They aren’t all designed to mean something like Michelle, ma belle / These are words that go together well. Some stand alone. Some narrate a story. But the ones he spooled out spontaneously are meant only as one more part of the instrumentation. The main meaning you’ll find is the meaning you put in them. Beck kept the best lyrics because he grew attached to them. In the process, they attached themselves to fans like me. As kid who was fixated on the way words felt in my mouth—middle school favorites were ‘corn,’ ‘pork,’ ‘slab,’ and ‘cheese’—finding a musician who played phonetics like a harmonica was a great match as an adult.

The 1990s were filled by a lot of innovative musicians, from Sonic Youth to Radiohead. There was nobody—is nobody—who spoke like Beck. Like the iconic faces of Winona Rider and Ethan Hawke in Reality Bites and girls wearing Doc Martins with skirts and plastic chokers, the line “You get a parking violation and a maggot on your sleeve” is the iconic ’90s—as ’90s as Lollapalooza and the short-lived, bottled, lemon-lime alcoholic drink Zima. But Beck’s best early lyrics continues to outlive the decade of their birth, because their beautiful, singular oddity still resonates today. Why?

First off, Beck is funny. After playing with a fire in a stove in “Modesto,” he sings: “Well it’s real and it’s fake / And it’s flamin’ like a steak / And she’s puttin’ out my face with the rake.”

In “Puttin’ It Down” he sings: “I’ll be better at kissin’ when my teeth are all missin’ / And the silverware’s burnt / And I’m eating with my fingers.”

You gotta love someone with a sense of humor.

Second, he surprises you, both with original lyrics and by delivering the unexpected. He twists familiar sayings like “Monkey see / Monkey do” into “Monkey see / Monkey die.” And by improvising crazy word combinations, he gives birth to crazy concepts, letting you view your world in a fresh, sidelong way just as comedians do. He sings out ideas like a drive-by body piercing. He invents “Rollins Power Sauce,” an imaginary thing inspired by Black Flag’s muscular, sweaty lead singer Henry Rollins. He sings the idea of “taking a leak into your brother’s cup,” and the self-effacing line: “Personality test / I failed with the best.” He scoffs at capitalism: “When they ask you for credit / Give them a branch.” He mixes the earthly and the existential: “Cut a hole a floor and see / Just how close to hell we’re standin’.” In “The Spirit Moves Me” he sang, “You can call me once a week / Tell me where I been.” Look at that on paper, as an idea: that someone can be so lost, or drunk, or spaced out, that they rely on others to narrate their life for them. Where have I been? Please tell me. What a funny idea. (It’s reminiscent of his other line: “There’s no map that can tell you where you were.”) And don’t forget the great ideas packed into the song “Sissyneck”: “Sitting in the jail house / Trying to learn some good manners,” and “If I could only find a nickel I would pay myself off tonight,” and how “Nobody knows when the good times have passed out cold.” “Sissyneck” is a lyrical treasure-trove. The chorus:

I’m writing my will

On a three dollar bill

In the evening time

Beck’s teenage comedy went beyond lyrics. Besides its title, the 1994 Steve Threw Up single included comical, scatological info on the insert. It said it was “Made in 19666,” recorded at Poop Alley Studio, and it listed Side A as “Side 2,” and Side B as “Side 3,” just to fuck with you. Never mind that it was released on a record label named Bong Load. The Loser single said the B-side “Alcohol” was recorded in 1958. It’s completely adolescent, and it’s fun.

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, by the mid-90s, I needed levity. Hardcore Bad Brains and serious Pearl Jam and screeching Smashing Pumpkins fed my spirit and energized my life, but a diet of loud fast guitar music had deprived me of certain nutrients, or at least, it revved my nervous system harder than it could handle for that long. It was the same way I’d deprived myself of guitars during my Depeche Mode years: Deprivation made the pendulum swing, and it swung hard for goofy Beck. I’ve always been serious and deep, a Gemini who broods and laughs in equal measure. Beck helped direct me toward a healthier middle ground, where I could embrace solemn, dark, moody stuff and then flip the switch to wacky, slapstick, nonsensical stuff that also made your booty move. These opposing sides all resides in one vessel now, rather than silos as they did during adolescence. But before I could rediscover silly me, I needed to court my own darkness with songs like Jane’s Addiction “Kettle Whistle.” I needed to embrace self-destruction with Alice in Chains and explore reality’s hazier dimensions with Monster Magnet’s Spine of God album. As Jane’s singer Perry Farrell said, “Just playing with darkness, that’s like half an idea. I need to know more.” While Beck sang about choking on a breath mint, his lyrics cleansed my palate during the Grunge years.

His early lyrics also work because they’re fresh. Countless musicians wrote incredible lyrics, from Jeff Tweedy to Patti Smith to Wu-Tang Clan, but no one talked like Beck, combining Blues motifs (“Clean my headstone when I’m gone”) with blue-collar American culture (food stamps, trailer parks) and indie rock language.

The scalps of zero hear the call

Rubbing in a blind man’s running hall

With the canker sores and the robot pill

Throwing imbeciles on the window sills

Over the course of his 30-plus year career, certain words reappear in his songs: brains, bones, matchsticks, cigarettes (“cigarettes were smoking by themselves”), transistors, tongues, hollow trees, hollow logs, cold (cold brains, cold bread), and piles. He loved the word ‘pile’ because he could enunciate it: PI-yull or PIIII-yu-lll. As much as he marble-mouthed certain words and could slur, he was ultimately about enunciation, about stretching sounds. Back in the ’90s, there were a lot of cans, whisky, whisky in cans, waste cans, recycled cans, brains, bread, disease, hostages, suitcases, force fields, toast, hobos, winos, steaks, trash, flapjacks, fast-food, beige, and brown, Satan, trucks, and snakes. Numerous snakes. And not just a snake, a “snake on the ceiling.”

His obsession with animals runs through all his early stuff.

In “Corvette Bummer” he sings: “Gonna fly like a squirrel, gonna swing like a chicken / Gonna weed-whack a plate of noodles in the afternoon.”

Pigs stand on levees in “Electric Music and the Summer People.” People run “like a flamin’ pig” in “Beercan.” In “Minus” he sings: “In the garbage glasses / With the crutches of frogs.” Elsewhere he’s “Riding the scapegoat.”

He was especially enamored by chickens and birds. In “Beercan” there are “Swirling chickens get caught in flight / Out of focus and much too bright.” In “Soul Suckin’ Jerk” he throws “chicken in a bucket with a soda pop can.” Silver chickens make a fuss in “Lemonade.” He even wrote a song called “Styrofoam Chicken.” His most famous animals might be the slab of turkey neck that’s hanging from a pigeon wing in “Loser.” Another famous Beck line is “Hijacked flavors that I’m flipping like birds.”

His songs feature lots of flipping, flapping, leaping, and flying. And laminating, decapitating, limping, throwing, and melting. He loved strong verbs because of their specificity and how they felt in his mouth: “I stomped and I stormed / And I passed out in your dorm / Then you hustled me outside / I couldn’t catch a ride.” Just like he liked the word ‘busting’ because he could over-enunciate it: “She’s busting out on to the scene / With nitemare bogus poetry.” The same held true with hard consonants in ‘chuck’ and ‘bucket,’ though he’d gladly accept any soft word like ‘manure’ with the bonus scatlogy sprinkled on. He was in that youthful stage of discovering the sonic joy of words while discovering his own power and celebrating bodily functions: rancid, squalid, moldy meat.

His adolescent sense of humor resonated with me as much as his youthful self-esteem did, on display in his song “Feel Like A Piece of Shit (Mind Control).” But some lyrics implied a wisdom you didn’t expect from someone singing about chickens, like in “Cyanide Breath Mint,” where he sings that people are “Shaking hands with themselves, hanging onto themselves” and how “It’s the positive people running from their time / Searching for some feeling.” He was an observer, a traveler, a person of the world. At his best, he transformed his observations into something poetic. “Like a frying pan when the fire’s gone” is evocative and unique. So is the idea of “Waiting like an ashtray for the butt” and “Chockin’ like a one-man Dust Bowl.” (Or is it ‘dust ball’? I can’t tell.) “Will you put me inside your TV tonight,” he sings, “’Cause you’re treating me like a re-run.” A guillotine in your libido sounds like a brilliant way of framing religious guilt around sexual urges, even if he didn’t mean it that way. In “Soul Sucking Jerk” he sings “I got bent, like a wet cigarette.” That line always grabbed me. I smoked. I’d doused cigarettes and knew exactly what he meant. “Getting bent” was an old description of getting angry and getting intoxicated. And it was one he’d clearly encountered during his days listening to old folk and Blues records and hanging with other musicians. He even named a homemade tape Don’t Get Bent Out of Shape. Even if it wasn’t an original description because he’d inherited it from the wider world, it was original to me, because this was the first time I’d heard it. And its visual power and concision encouraged me to write better descriptions as I started trying to become a writer myself.

No matter how much “good” poetry you read by legends like e.e. cummings, and whatever you think of Beck’s wackiest lyrics, the first verse in “Pay No Mind (Snoozer)” is powerful stuff:

Tonight the city is full of morgues

And all the toilets are overflowing

There’s shopping malls coming out of the walls

As we walk out among the manure

You can call his collages “free verse,” as AllMusic critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine did in his review of Mellow Gold, but that phrase implies pure improvisation, even a lack of control, and his lyrics are more than a guy whose head is spinning around like in the Exorcist, haphazardly spewing words. Sure, Beck tossed off countless songs. So many in fact, that they sound in-the-moment. But unlike free verse, he labored over so many more. He had an agency that “free verse” doesn’t credit him for, suggesting that he never sat down to revise any lyrics, that he didn’t test them at different shows or work them out. Come on. He didn’t just keep the first thing that came to mind every time. He wrote “Pay No Mind” at age 18 or 19 and released it at 23. Those lyrics are powerful because he revised so many different versions of them. Like the best poetry, his most potent lyrics surprise you, and their freshness rewires your brain, blowing cobwebs off your tired, worn down, repetitive synapses. Beck’s synapses don’t seem to ever tire.

Even his songs which have the most beautiful music have insane lyrics.

Musically, “Modesto” is beautiful. Its mixing of acoustic and steel guitar is a simple country dirge, breezy and shimmering. It’s a country song and tells as a sad story, if you can piece it together. But the way he sings his wacked out words is part of its beauty. He pronounces, over-emphasizes, holds them like he’d play a guitar. If he’d written any of those lyrics in a simple, free-associating improvisation, the words that made the final cut were clearly the result of labor—if not revised for meaning, then revised for how they sounded coming out of his mouth. Who else could sing “staring through a bag of Frito-Lays” with such heartfelt, lonesome, mournful beauty? Melody and intonation are some of the reasons his lyrics’ meaning doesn’t undermine their effect on the listener, just as intonation was why he loved singing words like “bag of Frito-Lays.” He was young. He loved messing with musical convention as much as he loved eating cheap junk food. You don’t hear Frito-Lays in songs, so he put it there, and in that way, he birthed something new.

Mike D of the Beastie Boys heard a natural fusion of eccentric, random lyrics and acoustic guitar. “He fits into the nomadic folk tradition of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, the whole traditional coffeehouse balladeer tip,” he told Spin. “But his hip-hop side legitimizes Public Enemy as the real folk music of the ’80s, because he draws on that aspect just as much as on anything else that he’s picked up along the way.”

It’s no surprise that he sustained this level of creativity for the past 30 years. As an imaginative original who was consciously laboring over his music, lyrics, and videos, he’s been able to create a vast, varied catalogue that includes weird raps, Grammy-winners, and melancholic albums like Sea Change, an album that Hank Williams would love and that doesn’t sound a bit like Mellow Gold.

But who was this lunatic lyricist? And where did he come from?

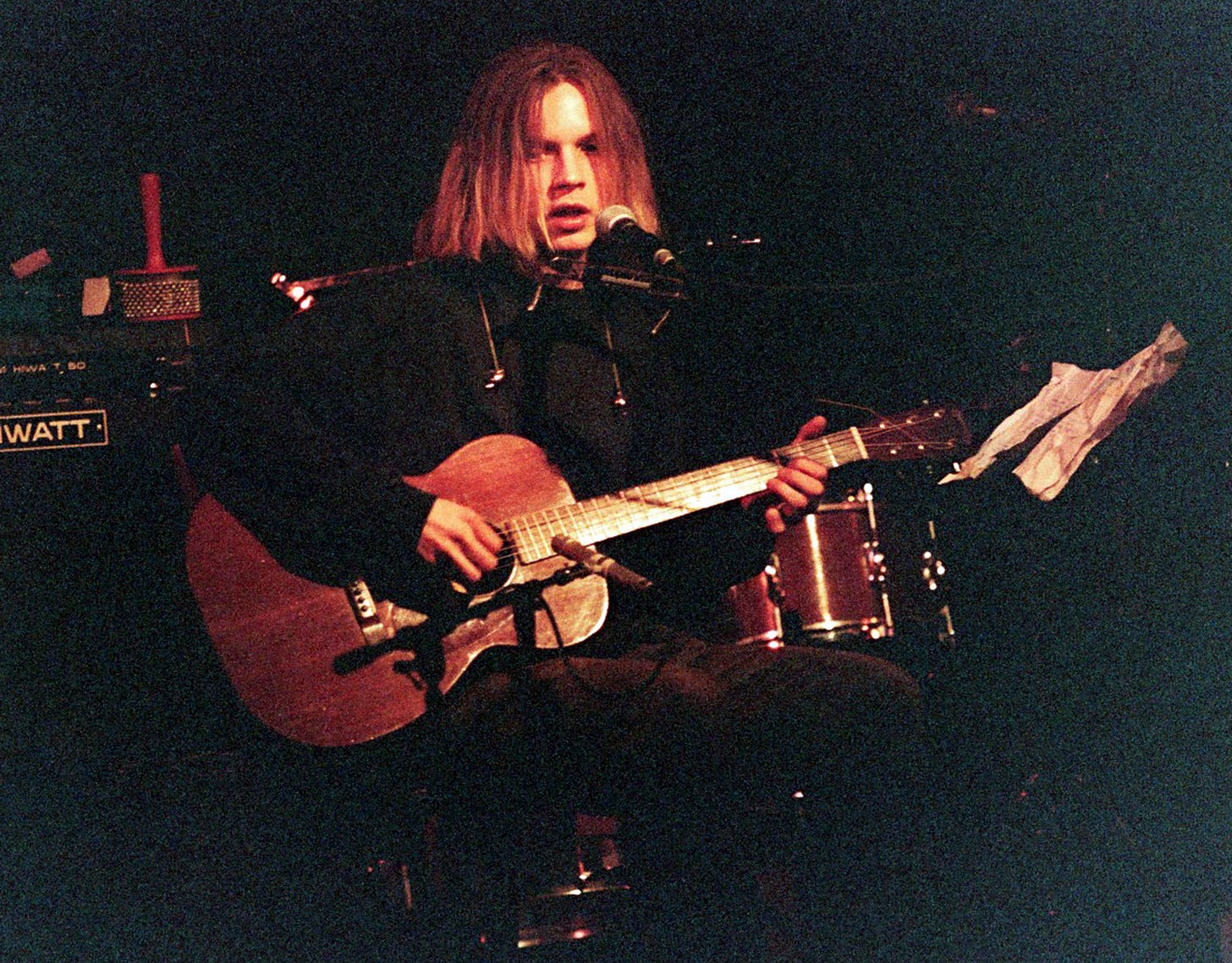

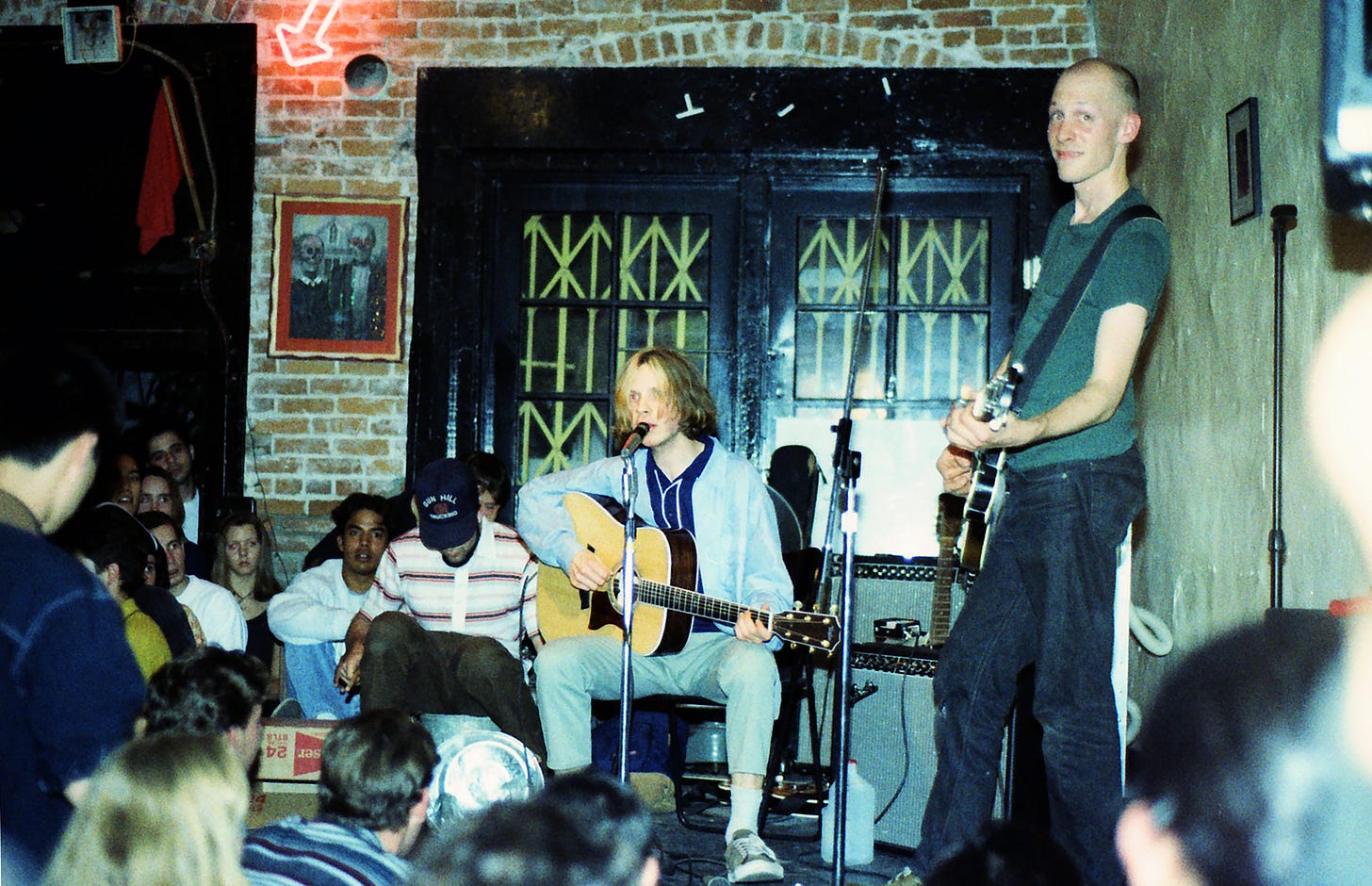

Before Beck became a sophisticated, seven-time Grammy winning songwriter, he was a beer-drinking, messy-haired, ramshackle poet whose lyrics were as loose as his acoustic guitar strings. He famously used a leaf blower to blow debris off the small coffee shop and club stages where he played—joints like Al’s Bar, the Gaslight, Onyx, and Raji’s—wore a Stormtrooper helmet and got onstage between local bands’ sets, often doing warmups for Possum Dixon and Ethyl Meatplow, to improvise acoustic songs about everything from the devil to minimum wage labor—whatever came to mind. He probably used his own leaf blower, since blowing leaves was one of his day jobs. He was trying to get audiences’ attention.

“I’d be banging away on a Son House tune and the whole audience would be talking,” he told Entertainment Weekly in 1997. “So maybe out of desperation or boredom, or the audience’s boredom, I’d make up these ridiculous songs just to see if people were listening.” In “One Foot in the Grave” he sang: “I was sittin’ at home cooking up a steak / Satan came down dressed like a snake / Well, he called my name as I turned up the flames / Then I realized I was out of mayonnaise.” You can hear the audience laugh on the recording. You’d have to be joyless not to laugh. In the early ’90s, he had countless one-offs like that, including “Weak Ass Shit” and “Lefty’s Dead,” that he threw at audiences and never took back. “I would always sing my goofy stuff, because everybody was drunk, and I’d only have two minutes,” he said. “That was my whole shot.”

Even as he grabbed audiences’ attention with his goofy stuff like “Mmmmmmmmmm,” he wrote loads of very not-goofy-stuff, like the moving acoustic Blues “Static 1,” “The Way It Seems,” “Hard to Compete,” and “It’s All In Your Mind.” Beck was primed for this mix of depth and nonsense. His life, like his art, was warped, free-range, unconfined. For us kids in the ’90s, Beck came out of nowhere, but his emergence was a long time coming.

Born Bek David Campbell in 1970, his family initially lived in a boarding house in downtown Los Angeles before moving to a seedy area behind the famous Egyptian Theatre, off Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. His mother Bibbe Hansen was an actor and visual artist who worked office jobs and had appeared in an Andy Warhol films as a teenager. His father David Campbell was a composer who’d written string sections for musicians like Carole King and played bluegrass on the street. Beck had seen different sides of the music industry and artists’ life throughout his childhood. Riding his bike down Hollywood Boulevard as a kid also exposed him to street musicians and punks. After his parents divorced when Beck was nine, he barely saw his father, who started a new family, and Beck shuffled between his mom’s in Los Angeles and his maternal grandparents’ house outside Kansas City, Kansas. “I had kind of a weird home,” he told Rolling Stone. “I think they were kind of concerned.” Beck’s grandfather was a Presbyterian preacher who played church music and hymns at home. “That music influenced me a lot,” he said, “but not consciously.” His grandfather kept encouraging him to become a Christian, so by age 12, Beck quit visiting. Instead, his multicultural, hip-hop Los Angeles of taco trucks and alienation would influence him as much as his family.

After the divorce, Beck’s mom moved him and his half-brother Channing to Hoover and Ninth streets in the rough Pico-Vermont area of central L.A. “It’s closest to the vibrant-but-tough area of MacArthur Park,” writes The Ringer, “if you had to pick a place, but it’s really something of a no-man’s-land, connecting Westlake with Koreatown and the historically Salvadoran neighborhood of Pico-Union. Beck’s five-person household, which often included his aunt and soon included his first-generation Mexican American stepfather, stayed in a one-bedroom apartment. Beck and Channing slept on the couch or in a sleeping bag on the floor.”

“I would say we were economically depressed,” Beck said in Rob Jovanovic’s 2000 biography, Beck! On a Backwards River. “We were basically living in a ghetto. But I wouldn’t want to sell myself as some kind of rags to riches story because that reduces it to something soulless. It was an impoverished childhood, but it was rich in other ways. Where I grew up wasn’t your typical, homogenized, one-track frame of mind—there were a lot of other things going on. Everyone was outside all the time, there were mariachi bands, animals running down the middle of the street.”

He was the güero—the golden-haired white boy—he sang about in 2005. The experience was formative. Animals came to run through his songs. He learned hip-hop and sang in Spanish. But it was tough. He felt like “a total outcast.” Kids constantly threatened to beat him up, chased him with lead pipes, so he dropped out after junior high at age 14, working odd jobs loading trucks, driving a forklift in a South-Central warehouse, and blowing leaves. “I was left to my own devices a lot,” Beck said. That freedom came to define his musical aesthetic.

As a teen, he liked punk rock, Pussy Galore, and owned the Xanadu soundtrack. Blues changed his life at 17.“I was at a friend’s house and we were hanging out and his dad had a bunch of records,” Beck told the LA Times. “He had this Mississippi John Hurt record and the cover was just a close-up shot of his sweating, old face and it looked pretty cool. So, I stole it. It totally blew me away. I’d never heard music like that before, but it was exactly the kind of music I wanted to hear. I wasn’t into that much music before.” He’d never heard music like Hurt’s. “This wasn’t some hippie guy fingerpicking in the ’70s, singing about rainbows. This was the real stuff. I stopped everything for six months and was in my room finger picking until I got it right.” The Blues’ humanity defied expectations. He first thought, Wow, this is going to be crazy. “But when I took it home and put it on the record player, it was this droning, deep, slow, warm world that just let you come in and be there with him. All the music I’d ever heard before that was just big beats and drums pumping and everything. It never really gave you any room to step in, look around, and breathe the fresh air.” Mississippi John Hurt led him to Skip James and Blind Willie Johnson and folk by Woody Guthrie. Alone, all he needed was an acoustic guitar to entertain himself for hours. “My first shows were on [city] buses,” Beck remembered. “I’d get on the bus and start playing Mississippi John Hurt with totally improvised lyrics. Some drunk would start yelling at me, calling me Axl Rose. So I’d start singing about Axl Rose and the levee and bus passes and strychnine, mixing the whole thing up.”

In addition to L.A. and K.C., Beck spent time with his paternal grandfather Al Hansen in Europe, a member of the experimental Fluxus art movement. “He collects cigarette butts and glues them together and makes pictures of naked ladies, then sprays the whole thing silver,” Beck said after he got famous. “His stuff was taking trash and making it art. I guess I try to do that, too.” That came later. At first he was a folkie.

“I was just constantly romantically envisioning Woody Guthrie-type America — just traveling around and singing,” he told Option magazine in 1994. The reporter conducted the interview while Beck folded clean clothes at the Super Giant Wash laundromat in Highland Park. He described the vintage Sesame Street, Bert Reynolds, and Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup t-shirts in his collection, and described his formative years. “So one day I saw this commercial on TV about a Greyhound bus ticket to anywhere in the U.S. for like $40.”

In 1989 he and his girlfriend left LA on a bus with only his guitar and eight dollars in his pocket and moved to New York City. “She disappeared and I was kinda left to my own devices again,” he remembered. “So I kinda started hanging out on the street in the Lower East Side.” There he found kinship in what became known as the anti-folk movement but which he described as “this whole kinda punk-rock-folk scene and noise-music-chaos-poetry-underground-basement-40-ounce-malt-liquor-being-crazy scene”. That mix of acoustic music and punk spirit was his kind of mix. “Punk was always sort of my favorite,” he said. “Here was a whole scene with people with just acoustic guitars punking out really hard.” Despite remaining creative, he found little stability. He couch surfed. He worked odd jobs like he always had. He couldn’t even find a job that first New York summer, but he played music constantly. “The whole mission was to destroy all the clichés and make up some new ones,” Beck told Guitar Player about his anti-folk friends. “Everybody knew each other. You could go up onstage and say anything, and you wouldn’t feel weird or feel any pressure.” That gave him the freedom to write the way he wanted, like he had the freedom to live however he wanted, and it set the stage for the music he’d write in the coming years. “I dunno,” he told Option, “maybe for me it was just my age—I was 18 or something—but it just felt great. It was such a special time. Suddenly I was turned on to the whole world. Being 18 really is such a turning point. And being in New York at that time made it so much better. You could write your own music, get drunk, and not really care about anything.” This period before “Loser” has become the stuff of myth, and his New York period was when folkie Beck became what one fan described as “psychedelic hillbilly Beck.”

“I would go to the Chameleon [club in the East Village] for the open-mic night and play Woody Guthrie or Mississippi John Hurt songs—which was my whole world at the time,” said Beck. “I didn’t even want to know about anything else. But [the booker] Lach wouldn’t book me for a whole night unless I wrote my own songs. So I said, ‘OK.’ And I went and got a pen and paper and wrote five songs about stuff like pizza, or waking up after having been chain-sawed in half by a maniac—stuff like that. He finally gave me a Friday night.” But he barely scraped by.

For a while he slept on the couch of a musician named Paleface, and they played open mic shows together. When he tried to rent his own apartment in Manhattan, it didn’t go well. “When I met the woman to exchange the money and the key, she somehow convinced me to give her the money, and that she was going to give me the key in two days—she disappeared,” he told Pitchfork. There was no apartment. She was addicted to crack. “I really loved living in New York; if things had worked out differently, I would have stayed there.” But after two broke years hustling, he couldn’t stomach the idea of another broke-ass winter without his own place, so he moved back to Los Angeles in early 1991. “I was tired of being cold, tired of getting beat up,” he said. “It was hard to be in New York with no money, no place, no honey, no thermostats, no spoons, no Cheerios.”

Over the years, he’d worked as a mover, a YMCA photo ID assistant, had painted houses, washed dishes at a bakery, and stocked merch at a gift shop. In LA, he worked more low-paying jobs, specifically, as Vulture tells it, “bouncing between a video store in a strip mall, a garment factory in South-Central, a movie theater, and a restaurant dish room [in 1991].”

While Sub Pop was taking over the world with their screaming longhaired bands who stomped their combat boots on the stage, Beck was doing his own weird thing. He struggled to get gigs. “If you were around the scene in Los Angeles at that time,” Beck said, “I was the least likely tipped for success. Every band I knew or played with had flyers and properly recorded demos and contacts; I couldn’t even get a gig. …The only way I was allowed to play was by convincing bands to let me do a few songs while they set up. That went on for years.”

He played music however he could, be it at a backyard party or in a city park. He drank cheap beer, wrote uncommercial songs, and perfected his fingerpicking. Sometimes he rapped between songs at shows and got people in the audience to beat-box into the mic. He eventually caught the attention of someone with music industry ambitions: Tom Rothcock.

“What hit me about Beck was that here was this self-contained folk artist who’d be great to make records with,” Rothrock told Rolling Stone. Rothrock had started the indie label Bong Load with Rob Schnapf and Brad Lambert, and he happened to see Beck play at Jabberjaw in the summer of 1991, shortly after Beck left New York. “And in between bands this guy bum-rushed the stage with a jazzercise sticker on his acoustic guitar,” Rothcock recalled, “and I was blown away. I just started Bong Load, and we had stuff in the can. But I went out back to talk to him after he finished performing and asked him if he was into hip-hop. I knew it was a longshot, because the set he played was straight up Lead Belly/Woody Guthrie/early Bob Dylan folk presentation. But he says to me, ‘Oh yeah, yeah. I really like Public Enemy and Chuck D.’ And I was like, ‘Oh perfect!’ We were trying to do some kind of hip-hop folk album and we tried it once, but it flipped the songwriter out because we changed it up so much. Beck, meanwhile, got a huge grin when I approached him with this [idea], and he says, ‘Wait a minute, you can fuck stuff up?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah, that’s the idea.’”

They traded phone numbers.

Rothrock suggested Beck play his folk songs for a guy named Carl Stephensen who’d worked as a hip-hop producer for Rap-A-Lot Records in Houston and now had a home studio. Stephenson’s home studio was an eight-track tape recorder in his living room.

A symphony kid from Washington State, Stephensen left his grocery story job in Olympia to work for Rap-A-Lot in Houston, home to the popular Geto Boys. As much as he loved seeing how DJs like Ready Red pulled samples from old soul and funk records, he didn’t jive with that scene’s violent misogyny, so he moved to LA to keep working in music.

“So we went to this guy’s house and I played him a few of my folk songs,” Beck told Option. “He seemed pretty all-around unimpressed. Then I started playing this slide guitar part and he started taping it. He put a drum track to it and it was, you know, the ‘Loser’ riff. I started writing these lyrics to the verse part. When he played it back, I thought, ‘Man, I’m the worst rapper in the world—I’m just a loser. So I started singing, ‘I’m a loser baby, so why don’t you kill me.’ I’m always kinda putting myself down like that.”

Over the course of six hours, with Beck’s $60 guitar and Stephenson’s $30 Radio Shack microphone, they recorded one of the most iconic songs of the 90s. As Pitchfork wrote, “Beck later remembered having to finish vocal takes before Stephenson’s girlfriend wanted to get in and cook dinner.”

As Pitchfork wrote:

The way Stephenson remembers it, Beck Hansen was a street busker with a bad haircut. But he had a mischievous sense of creativity and no attachments to his own artistic self-image… After all, he liked rap—the immediacy, the beat, the sense of performance. …Mostly though, fashioning himself as a kind of rapper was a chance for Beck to undermine the sanctity of what it meant to be a white guy with an acoustic guitar. That he understood hip-hop as an extension of folk music rather than a betrayal of it—the way rap spun meaningful, entertaining stories out of everyday life using equipment anyone could get their hands on—felt insightful, even subversive, especially at a time when we were starting to digest the reality that grunge was just classic rock after all: the same quest for glory, the same macho, self-serious dream.

When they dashed off “Loser,” Beck lived in a rooming house in Los Feliz and alphabetized VHS tapes at a video store for $4.25 an hour. According Vulture, “his single goal in life was for his friend who ran a house-painting business to take him on so that he could make $5.” After the session, he got back to writing his free-form folk songs like “Scabmeatfaceliftsuctionmonkeyetc” and recording weird homemade demo tapes like We Like Folk...Who Cares...Destroy Us, Buck Fuck Iowa, and Don’t Get Bent Out of Shape to sell at shows. He literally forgot about the session until Rothcock called him a year later, saying he wanted to put “Loser” out as a single.

Bong Load released 500 copies of the “Loser” single in March of 1993. At the time, Beck was, in his words, “living in a shed behind a house with a bunch of rats, next to an alley downtown. I had zero money and zero possibilities.” Beck recorded more homemade tapes, including Fresh Meat + Old Slabs (song: “Deep Fried Love”) and Golden Feelings. Local fans passed those tapes around. As Bong Load worked to get “Loser” on the radio, Bong Load also released Beck’s Steve Threw Up single in 1993, and the independent Fingerpaint Records released his A Western Harvest Field by Moonlight 10-inch. A decade later, those all became artifacts of his oddity, because the tossed-off, folk-rap experiment turned the impoverished obscurity into an international star in 1994, at age 23.

LA’s college radio station KXLU played the single first. Soon after, Geffen A&R man Tony Berg heard it and played it for Santa Monica College radio station KCRW music director Chris Douridas, who played it on its popular show Morning Becomes Eclectic, which was broadcast by NPR. Then LA’s larger commercial alternative station KROQ picked it up. “It was one of those unbelievable finds,” said Douridas. “I called the record label that day and asked to have Beck play live on the air. He came in that Friday, rapped to a tape of ‘Loser’, and did his song ‘MTV Makes Me Want to Smoke Crack.” That night Beck played a gig at Café Troy, the small poetry club that his mother Bibbe started, and record label talent scouts came to check him out. Suddenly everyone wanted him. A bidding war ensued, with Warner and Capitol trying to sign the hit-maker enigma.

“I didn’t really know what an A&R person was until maybe last July,” he told the LA Times. “I thought an A&R person was like somebody who worked at A&M [Records]. I had A&R and A&M mixed up.” He knew enough to be wary.

As major-label executives and what he called “people in their BMWs” descended on his little shows, he brought his leaf blower to keep them in check. “I came out and blew the leaves at these people,” he told The Guardian in 1999. “It was sort of a statement. Like: I know where they come from, and what kind of world they live in. They all have some guy, some undocumented worker, who comes to their house once a week and blows their leaves for them. I wanted to let them know that I wasn’t going to be their leaf-blower. …I wasn’t just some ready, willing musician, just aching to be exploited.”

“Loser” caught on so fast that people started bootlegging the single faster than Bong Load could press it. “I thought of ‘Loser’ as this fluke that I’d done messing around at a guy’s house in 1991,” said Beck. “I didn’t even have a copy of the song. I just remember it being a laugh, but some people heard it and liked it.” One YouTube commenter described the song as “a one-song-musical-genre…a sonic cul-de-sac.” Thanks to alternative stations like Seattle’s KNDD 107.7 FM, The End, the local hit got played up and down the West Coast and quickly went national across the growing network of alternative rock radio stations, helping, according to Billboard, “the song reach the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 as well as the top spot on the Alternative Songs chart.” Wisely, Bong Long got Beck to record his full-length debut, Mellow Gold, on an 8-track in his living room, as cheap and DIY as he’d always been.

“And it got to the point where there was nobody who could front the money to print [more] copies [of ‘Loser’] to get it out there,” Beck said. “So I just ignored it for six months and thought it would go away. I told all the labels no, or had stopped returning their calls. But then we’d put together all these demos, which became Mellow Gold, and the only way to put it out was through one of these labels that had the interest and the money. I literally didn’t have the $4,000 to print the copies. Now, I wish I’d borrowed the money and done it myself, but at the time, there was a really good group of people at Geffen, people who had been at indie labels like SST and Blast First in the ’80s and had worked with people like Sonic Youth. Plus, indie labels didn’t want anything to do with me because ‘Loser’ had already become a big hit song. There was such a stigma with that. And Geffen understood the indie world, but they were putting out big records and selling a lot of copies and getting videos on MTV at the same time.”

In December 1993, A&R executive Mark Kates signed Beck to the Geffen subsidiary DGC. Anchored to lucrative rock dinosaurs like Aerosmith, the fact that Geffen had also signed modern bands like Weezer, Hole, and Veruca Salt helped sweeten the deal. Ultimately, Beck chose Geffen because the label provided him the most creative freedom. Even though it paid him less, it allowed him to do things like release two other albums on two different indies the same year he released Mellow Gold. Bong Long released it, and DGC picked it up.

Corporate support gave him money to keep writing and recording, to release innovative videos for the MTV generation, and tour the US, Europe, Japan, and Australia in 1994 and 95. It also gave him the freedom to be his weird, shape-shifting self.

“I remember seeing Beck play this live at a little coffee shop called The Haven in Pomona back in 1994 when Loser had just hit the airwaves,” said a fan on YouTube. “He played a dozen songs or so, but not Loser! LOL, he was getting ready to pack up, the crowd got restless at not hearing the song that had brought them there, then he finally relented and played it. He signed my flyer for the show with ‘666’ surrounded by a heart. Freaking weirdo.”

Mellow Gold came out in March 1994 and went gold that May. By August 1995 it was certified platinum. In Rolling Stone, writer Michael Azzerad, author of the incredible book Our Band Could Be Your Life, called Mellow Gold “Ultra-surreal hip-hop folk.” Azzerad wasn’t fully convinced by it, but he felt it captured the feel of the times, some sort of gestalt. “Virtually everything embodies the stereotypically manic-depressive slacker mind-set,” Azerrad wrote.

In the same year in the same magazine, Beck described the first time he saw the “Loser” video on TV and heard himself labeled a slacker spokesman for Generation X. “I was up in Olympia, Washington,” he said, “and someone called up and said they were going to premiere the video. The guy on the air was talking about all this slacker stuff, saying that ‘Loser’ was like some slacker anthem or something. I was like ‘What?’ I said, ‘Turn off the TV.’ Slacker my ass. I mean, I never had any slack. I was working a $4-an-hour job trying to stay alive. That slacker stuff is for people who have the time to be depressed about everything.” Beck didn’t even have much time to watch TV. “I’ve always tried to get money to eat and pay my rent and shit, and it’s always been real hard for me,” he told Spin.

So many critics needed “Loser” and Beck to mean something more than they did, just like we listeners need lyrics to mean more than they often do—or mean anything. Many journalists had inherited this question about whether the 23-year-old wunderkind was a one-hit wonder, or if his debut album captured the zeitgeist in some wide angle lens way. Otherwise, if the music didn’t capture the spirit of the early ’90s, and if Beck was capable of offering the world more than a single joke song, then those critics would just be reviewing another record by a weird young dude who they couldn’t easily figure out. Discussing Mellow Gold in Option magazine, Marc Kemp called Beck “an amalgam of late-20th century multi-media fallout.” “If Dylan had his finger on the pulse of his inquisitive generation back in 1966 when he declared, ‘Everybody must get stoned,’” wrote Kemp, “Beck seems every bit as in tune with his own cynical peers when in ‘Loser’ he commands, ‘Get crazy with the Cheese Whiz.’” The slacker generation/one-hit-wonder thing was all BS-meaning-making, some mass media version of cultural studies or something over my non-academic head. There was no issue there. “Loser” didn’t speak for a generation. It was just beautiful perfect nonsense. Couldn’t anyone write a revolutionary word salad song without it suggesting they were either lucky hacks or cultural spokespeople? And couldn’t their jokes appear on the same albums as deep, haunting songs like “Pay No Mind” or “Blackhole,” without one undermining the other? It was all such simplistic thinking. “It was a fun song to make,” Beck said. “It’s tongue-in-cheek, you know. It’s not some anguished, transcendental ‘cry of a generation.’ It’s just like sitting in someone’s living room eating pizza and Doritos.”

In 1994, music industry people gave Beck advice to ensure his longevity. Enjoy your anonymity, they said. People are going to recognize you on the street for the rest of your life. Don’t get angry and bitter like Eddie Vedder. Don’t choke on your own vomit like Jimi Hendrix. Kates, the Geffen exec who signed him, told him, “You gotta make sure this isn’t the peak of your career.” Kates also said: “He’s a smart guy. I’m not that worried about him.”

Kates was right. As Beck’s oeuvre shows, more of Beck’s best work laid ahead of him. By 1995, he played England’s famous Reading Festival. In 1997, he played Letterman. And in 1998 and 99, he blew peoples’ minds with two very different albums Mutations and Midnite Vultures, respectively. That was just the ’90s. And no matter how many times early critics called him a one-hit wonder, he worked hard to create music and imagery that proved them wrong. The fact that we still talk about early Beck in 2021 proves his abilities. He refused to be labeled a generational spokesman, a slacker, or a one-hit wonder. He spent a lot of time proving them wrong. In a sense, he spent his whole career proving them wrong, because he could never get over the ridiculousness of his career’s beginning. That’s one reason there are these two different Becks: the psychedelic, hillbilly folk weirdo at the beginning, and the mature, funny but sophisticated songwriter after Mutations. Another reason is the age when he got famous: 23. Guys are spazzes at 23. He released Sea Change at 32. The other reason for this divide is the biggest: He just has countless sides to his musical personality. And it is why fans can still argue about which Beck they like best. I’m not the only one who still loves early Beck. People around the world only listen to early Beck, finding his later stuff too polished, or lacking the necessary weirdness. Tape traders search only for demos and live recordings from before 1995. Some fans say that acoustic Beck is best Beck. Others like me say any Beck is the best Beck. There are so many Becks that you can take your pick and still enjoy agreeing to disagree.

He didn’t plan this.

“Believe me,” he told Rolling Stone in 1994, “all of this has fallen in my lap. I was never good at getting jobs or girls or anything. I never even made flyers for my shows.” He couldn’t believe the attention. He laughed it off, called it “all this ridiculous stuff,” smirked at the hype while being grateful for the opportunities and revenue that success brought. How could he believe that a one-off experiment in a stranger’s living room would afford him and his future wife, actress Marissa Ribisi, a historic, $3 million Tudor in Brentwood?

Early Beck responded to this in early Beck language, saying, “You just gotta rage against the appliance, man. The toast is burning, and you just gotta rip it out and free it before it fills the house with smoke.”

Later Beck responded in hindsight more conventionally: “It was disturbing to me that an idea or a song [like ‘Loser’] could become something so different from what you originally intended. It’s like if a friend took a stupid picture of you at a party on their phone, and the next thing you knew, it was on every billboard.”

Beck held his record release party for Stereopathetic Soulmanure at a run-down bowling alley. The records weren’t ready though, so they couldn’t sell any, but the band set up at the end of one of the lanes and the crowd loved it. Beck introduced “Loser” as “K-Rock Set My Dick on Fire” and clicked an overhead Miller Genuine Draft neon sign on and off to the beat. The next night was the last night before they started their long Mellow Gold tour. They played at Fuzzland, an underground club that changed locations for each show. Then they hit the road.

Even as his weird, one-off rap catapulted him to fame, he cultivated the other sides of his personality, which were always there, grafted to his roots. In March 1994, before beginning his world tour for Mellow Gold, Beck went into Sun Studios in Memphis to record some old Blues. In that hallowed room where Elvis Presley was discovered and Howlin’ Wolf cut some of his best songs, the 23-year-old Angelino performed “Stagolee” by his beloved Mississippi John Hurt, did Skip James’ immortal “Devil Got My Woman,” and who knows how many more. Beck kept all but two of these recordings to himself. Imagine. The longhaired kid who did the splits on stage and told audiences “Shave your face with some mace in the dark,” sitting in Sun Studios, privately playing some of the deepest Blues around. He’d already recorded James’ “He’s a Mighty Good Leader” for K Records. Even in this 20s, he was both an old soul and an adolescent, a coffeehouse teen, and a traveling Bluesman, or in his words: “I was over and under my age.”

Mellow Gold started with “Loser,” and the music that came after was gold but not mellow. The album ranged from noisy barn burners like “Motherfuker” to folk, bad acid trips to some very danceable jams like “Beercan.” It was insane. My friends and I were devoted to rock ‘n’ roll, and we had strong, asshole opinions about everything, which is why we saw so many killer bands play so many killer shows, from Nirvana to Mr. Bungle. Beck’s music stormed my snobby castle. Mellow Gold led me to potent B-Sides like “Alcohol” and his nitrous-huffing narrative “Fume,” (“There’s a fume in the truck / And I don’t know if we’re dead / Or what the fuck”) and to his freakier indie albums Stereopathetic Soulmanure and One Foot in the Grave, which mixed country, folk, Blues, and lo-fi surrealism, and which he also released in 1994, to prove his artistic range. He shouted some of my favorite lines of all time. “Drink my coffee with a hubcap! Yeah!” I’d sing that and the “Fume” lyrics around my friend Chris’s house and he’d get irritated, grumbling “What the fuck are you talking about?” I had no idea. Early Beck liked it that way.

In Rolling Stone in 1994, he explained: “The whole concept of Mellow Gold is that it’s like a satanic K-Tel record that’s been found in a trash dumpster. …Someone played poker with it, someone tried to smoke it. Then the record was taken to Morocco and covered with hummus and tabouli. Then it was flown back to a convention of water-skiers, who skied on it and played Frisbee with it. Then the record was put on the turntable, and the original K-Tel album had reached a whole new level. I was just taking that whole Freedom Rock feeling, you understand.”

When Odelay came out in 1996, I listened to it constantly. Funky songs that infectious don’t lose their booty juice. They contained too many sonic layers to exhaust. Albums can be riddles that provide endless fun. All the sounds that Vivian now asks me to identify had mystified me, too, and Odelay’s lyrics took months to learn. On my endless quest for more Beck, I found a whole 1994 radio broadcast from Olympia, Washington. I found songs on obscure ass compilations by Jabberjaw, Poop Alley Studio, DGC, and KXLU, and, best of all, on the bootleg Quodlibet, which contained four songs from a 1995 British Radio 1 session that were as good as anything he’d officially released. This early Beck accompanied me through my early life.

As a college undergrad, “Soul Suckin’ Jerk” had the thunder drums and explosive fuzz-tone bass I loved. The lyrics also spoke to my perceived sense of suppression as a low-pay laborer. Beck tells a wacky story about freeing himself from work. It had a beginning, middle, and end, even though many plot twists only connected to the last line chronologically, not logically. But “Big fat fingers pointing into my face / Telling me to get busy cleaning up this place” totally resonated with my idiot college attitude. I was a creative person. I photographed the city and explored the outdoors. With so much to create and discover, I didn’t think it was “right” to keep me at a Subway franchise on weekends and in a windowless university office during the week, stuffing professors’ travel vouchers into a spinning file cabinet. These professors got to travel with university money? For work? Fuck that. Beck lit his uniform on fire in a vat of chicken fat and ran away. Although no mean bosses yelled at me, Beck’s boss was a stand-in for every external force that demanded my time and forced me to act responsibly. “Well they got me in a birdcage / Flapping my jaw…” Working shitty jobs can definitely sell you short of your potential, but in college, that mostly meant keeping me from getting stoned with my friends in the middle of the day. I only had plans for big artistic things, not discipline. In the song’s middle section where he turns up the bass, yells through affects, and just jams, obnoxiously, aggressively: “I’m standing right here with a beer in my hand / And my mouth is full of sand / And I don’t understand.” I didn’t understand anything either! The difference was, when Beck sang “I ain’t gonna work for no soul sucking jerk / I’m gonna take it all back / And I ain’t saying jack,” he’d earned it. My coworkers in the university mail room were some sweet office drones who were surprisingly patient with the stoned longhaired file clerk who skated all sweaty to work. And the Subways where I worked? Two of my half-brothers owned them, both very nice guys. Yet I clung to my rebellion, because I was special, dammit, and I deserved to “take it all back.” Take what back, my free time? I got my first job in high school. Free time was all I’d ever had! This sense that work was the enemy of my freedom and creativity was the same reason Beck’s other anthem for wandering rebels, “Electric Music and the Summer People,” spoke to me: “Let’s don’t be like everyone else / With the one trip rooms / And the halfway house / Big black drums beating the night / Running away, that’s what I like.” Those were words to try to live by. “Out on the highway,” he sings, “I’m doing it my way.”

At age 21, when I started taking solo trips through rural California to write what would eventually become my book about the region 20 years later, Beck’s weird acoustic country songs “Rowboat” and “Modesto” kept me company. As I drove endless miles between farms that dominated the whole horizon, a lap steel wailed and Beck sang “Pick me up, gimme some alcohol / In your truck, playin’ the radio.” When he sang “This town is filled / With thousand-dollar-bills / Laminated songs / Contaminated lawns,” I knew what he meant. When he sang, “You’ll be strange / You’ll be far away,” he captured how I felt, parked in my truck on a narrow country road, alone among the fields of rural California, feeling like a freak for how my interests alienated me from my friends and the rest of humanity.

When I briefly got strung out on heroin (long story), Beck’s “Deadweight” played while I lay on the front seat of that same red Toyota pickup in Tucson, sweating through my first serious withdrawal, in 1998. As listeners do, I processed his lyrics through my own experience, interpreting his references to chemistry, drinks, disease, freaks, and parasites as allusions to a drug-using life like my own. “Deadweight” wasn’t about anything I could discern, but the lyrics spoke to my suffering, so they soothed: “You’re so alone today.” Yes, I was alone. In my car. And in bed and in the bathtub vomiting with cold sweats, aching bones, headaches, deadweight. Withdrawal symptoms resembled Beck lyrics. Beck saw right through me: “Is it true what they say? / You can’t behave / You gamble your soul away / Measuring the dreams, of this life seems / Like the gristle of loneliness.” What they said was true: I felt so alone with my poor decision to discard my dreams and gamble my soul away on heroin. Why couldn’t I behave? It was the 90s. Smack was everywhere, but that was an excuse. My misery transfigured “There’s no belief, no salt in the sea” into “There’s no relief, no soul to mercy,” because after three days of this there seemed no end in sight. “Don’t let the sun catch you cryin’.” In Arizona, the sun always found me. It’s a four and a half minute song, I thought, sprawled out in my truck. How many times would it have to play before my aching body felt better? Too many. But when he sang, “Like an ice age, nice days are on their way,” I hoped he was right.

I missed him on the Odelay tour. I skipped the 1995 Lollapalooza where he played the side stage, because my friends and I saw the first four Lollapaloozas, but when his Midnite Vultures tour came through Phoenix in 2000, friends and I went. He danced. We sang. The place went nuts for his brass menagerie. When he slowed down to play “Jackass,” my eyes teared up. It was one of my favorite songs of all time, and the first song to make me cry at a show. I didn’t understand the effect it had on the newly sober me, but I went with it, and once it opened the emotional floodgates, I cried at other shows, too. As he sang on an early album: “Late at night and the spirit moves me / And I don’t mind bein’ afraid.” Beck showed me not to fear my emotional responses to music or my range of musical tastes. But for me, early Beck wasn’t about emotion. It was about weirdness, surprises, and laughs.

The ’90s were a particular time and place that had a particular feeling. Every decade’s like that. Our ’90s was like the one you see in Heathers and My So Called Life. It was a lot of baggy pants, ugly-colored thrift store t-shirts with Mountain Dew logos on them. It was wearing a striped long-sleeved tee under a striped collared shirt. People smoked cloves. We bought overpriced import singles at Tower Records. MTV played on rotation, often just in the background while you played Nintendo. And of course, there was irony, and lots and lots of drugs. Beck’s early lyrics contain many ’90s motifs—cancelled checks, mini-malls, low-sodium diets, meth references (yellow sweat from his speed-takin’, truck drivin’ neighbors downstairs), and how MTV makes him want to smoke crack. Crack jokes are themselves very ’90s. Few things were as ’90s as hippies and the urge to antagonize them. Beck’s song “Nitemare Hippie Girl” nails the archetype perfectly:

It’s a new-age letdown in my face

She’s so spaced out, and there ain’t no space

She’s got marijuana on the bathroom tile

I’m caught in a vortex, she’s changing my styleShe’s a nitemare hippy girl

With her skinny fingers fondlin’ my worldShe’s a whimsical, tragical beauty

Uptight and a little bit snootyShe’s a magical, sparkling tease

She’s a rainbow choking the breeze

Yeah oh, she’s busting out onto the scene

With nitemare bogus poetryShe’s a melted avocado on the shelf

She’s the science of herself

She’s spazzing out on a cosmic level

And she’s meditating with the devilShe’s cooking salad for breakfast

She’s got tofu the size of Texas

She’s a witness to her own glory

She’s a never-ending storyShe’s a frolicking depression

She’s a self-inflicted obsession

She’s got a thousand lonely husbands

She’s playing footsie in another dimension

If you ever got stoned in a dorm room near a tie-dye wall tapestry, you know how accurate these lyrics are. I can’t even pick a favorite part.

Even as a surrealist, he wrote from real life. The B-side “Fume” went: “We had a can of nitrous and we rolled the windows up. …And I don’t know if we’re dead, or what. The fuck.” Oh, I thought when I heard that, he gets trashed like we do. No wonder his stuff’s so warped. But the song didn’t explain his aesthetic. He wrote “Fume” after reading a newspaper article about two kids who died from filling their truck with nitrous to get high. “The original idea of the song that I wanted to try to get at,” Beck said, “but it didn’t really work, (was) just that moment when they were crossing over from that highest peak, that highest nitrous high, that second that it turned to death. Just that second, I think, was the thing that I wanted to put into song.” He wasn’t glamorizing drug use. He was trying to understand peoples’ lives. Unlike me, he didn’t use drugs to try to engineer creativity. He was his own superpower.

He’d done the same thing in “Truckdrivin’ Neighbors Downstairs (Yellow Sweat).” Beck lived above two abusive speed-users. One day they got in a heated fight in front of the apartment building. It lasted 40 minutes. Beck was trying to record music in his apartment but the noise was too distracting, so he recorded them fighting with a tape recorder, then he left. “I had to stop recording my song. And it was strange because I was recording the music for the song; I hadn’t written words yet. And I couldn’t record anymore because they were too loud and I just left. I had to leave ’cause it was too hectic.” Driving around, the violence and dialogue stayed with him. “I was so shook up by the thing that I pulled over on the freeway and I just wrote the lyrics out, and then the next day came back and sang the lyrics over the song,” he said. “It was one of those experiences where life writes the songs. Which is good.” He put a few seconds of real fighting audio on the song, too, and another Beck classic was born: “Acid casualty with a repossessed car / Vietnam vet playin’ air guitar.”

That’s the thing: Beck had depth. He showed you your world in a fresh way. No matter how wacky he got, he’d still throw you a serious song like “Alcohol,” where he reckons with the drug that he’d constantly been boasting about on and before Mellow Gold. In “Beercan” he sings “Alcohol on my hands, I got plans to ditch myself and get outside” because “I got a drug / And I got a bug / And I got somethin’ better than love.” Beer was as much a part of his lyrical landscape as chickens. He even named a homemade cassette Beck, Like the Beer. But the song “Alcohol” is his mature counterpoint to “Beercan,” the sound of a young adult examining the flipside of fun and wondering if it’s time to put the can down. “Alcohol leavin’ me dry,” he sings over an ethereal strum. “Now it is time for pie / Taking them as they come / Alcohol, please give me some.”

Mark Kates at Geffen was right not to worry about him.

In “Thunderpeel” he screams: “Now I’m rolling in sweat / With a loaf of cold bread / And a taco in my jeans.” Maybe as he got famous and recognized the power of his platform, he also sensed that, as much fun as he was having, he’d have to write something serious if he wanted staying power.

“I didn’t take it all that seriously when I started,” Beck told Pitchfork. “It was a little bit of a stigma to being a songwriter or a folkie back then, so you had to hide that with a lot of humor.” The more comfortable he got wearing his heart on his sleeve, the more powerful his music became. That’s why Modern Guilt starts with three of his best—“Orphans,” “Gamma Ray,” and “Chemtrails”—and leads to another, “Profanity Prayers.” That’s why he came at us in 2002 with such crushers as “The Golden Age,” and why in “Lost Cause” he could sing: “This town is crazy. Nobody cares.” That line still slays me. It’s so pained, so forlorn. I felt it every time a car cut me off or I got stuck in traffic and looked around at all of us drivers, stuck in our cars so close to each other, yet out of reach. His lyric proves the power of concision, which the length of this essay surely proves further. All the lonely people, Paul McCartney sang, where do they all come from? A killer line, but it was Beck’s I come back to.

No matter how frequently he hid behind humor, his wisdom was always there. Measured in a sense of alienation, that 2002 Sea Change lyric is a lot like the 1994 lyric from “Crystal Clear (Beer)”: “There’s no kindness in this land.” So what does this mean for the weird songs? If the serious songs were deep, were the rest just a joke? How could one song sound like such a throwaway and another sound so polished and profound? When you laughed at the couple of couches asleep on the loveseat, you couldn’t tell if Beck was laughing at the whole idea of music itself. I think it just means he only got better with time. He quietly cultivated both sides of his personality: the plaintive finger-picker, and the adolescent spaz. Even in the ’90s, his music had such range that it includes comedy and poetry, jokes and tears, and by his own admission, he often hid chose humor because it was easier to laugh that be serious. Of course musicians evolve. Anyone who does anything long enough gets better at it. I’m talking about his oeuvre as a complex personality whose lyrics show completely distinct characters—the feral weasel and the striped-shirt sophisticate—and it somehow coheres.

Later Beck doesn’t undermine his weird lyrics. You just can’t look for too much meaning in them. We all tend to decipher the language, because that’s what language is supposedly for: communicating meaning, stories, ideas. Not with Beck. As people, we can’t help ourselves.

Just like publications love to rank songs by artists—“Top 30 Beck Songs, Ranked!”—fans spend a lot of time trying to decipher his lyrics, or in my case, going on and on about them. On his blog, one fan examined the lyrics to “Elevator Music” on The Information. When Beck sings “The ambulance sings along,” the fan writes: “A magnificent Beck line. The suggestion is that the ambient background noise of the wailing siren is meshing with Beck’s music-making in the foreground. But the emergency services vehicle isn’t disturbing the rhythm – it is integrated with the music (“sings along”). Life (music) and death (ambulance) are fused together here. The awareness of our mortality conditions both the creation and reception of art; art springs out of the mystery that is revealed to human consciousness.” It goes on for pages, just like this essay, maybe too long: “When Beck sings “I shake a leg on the ground / Like an epileptic battery man,” the fan writes. “‘Battery’ is also a military term, meaning a unit of artillery pieces (guns, missiles). This suggests bombardment: Beck is launching music at us. A ‘battery’ is also a power source. Beck will fill us, the listeners, with power through the grace of his music. This is what art can do: transfer energy from person to person, what is otherwise known as inspiration.”

Some people are lyric people, and some are music people. Music people don’t care as much about what the singer’s saying as long as we like the rhythm or melody. That’s why I love instrumental music as much as sing-alongs. But lyric people can tolerate bleh music if they like the lyrics’ message, or if the words tell a story or move them in a profound way. For them, lyrics are the song—like my very philosophical father-in-law, who loves songs like Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is.” (“I want you to show me!”) Many lyric people can’t get past early Beck. They’re the kind of listeners who can enjoy Sea Change or Morning Phase, because those albums’ lyrics are the most comprehensible, their song structures the most conventional. I get that. Beck’s babble can get in the way of the music, like in “Crystal Clear (Beer).” It’s a beautiful Blues, fingerpicked like Mississippi John Hurt. But Beck sings:

Plastic donut, can of spam

There’s no kindness in this land

Better not let my good girl catch you here

He could erase the vocal track and have an ethereal, eerie Blues with a graveyard kind of beauty. But it seems like he ruins the atmosphere with lines like “Just a muscle in a bag / Throw my baby, don’t let her sag.” It’s the Blues meets high school, and that doesn’t always work. It took me a while to get past these lyrics, but the more I sang them, the more they faded into the background, becoming one more element of this song’s haunting melody, until I no longer heard them at all. Bag. Sag. Spam. The guitar picking eventually came to dominate my experience of the song, not the gibberish. It’s a strange process, but it happens if you let it.

After decades of mystifying listeners with his music, Beck’s lines in “The Spirit Moves Me” couldn’t be less true:

Lately I been spittin’ out things

That I didn’t mean to say

But that’s alright, now

You don’t listen to me anyway.

Ultimately what I’ve learned is that Beck has matured, and I have too, but not completely. I still enjoy saying “multiplying meat.” Oddity still surprises me. Early Beck’s particular oddity conjures my past, and after years of resistance, I’ve finally accepted that a little nostalgia can be fun sometimes, if you just go with it. As he sang in 1994: “New age, old age, totally lame / Straight to the middle of the road.”

Now I’m passing the torch to Vivian, just as Beck was “Passing the dutchie from coast to coast / Like my man Gary Wilson, I rock the most.” And in a robot voice, while breakdancing, the next generation sings:

Where it’s at

I got two turntables and a microphone

For Vulture, the 42-year-old Beck looked back on “Loser”:

“You wouldn’t in a million years go, ‘This is my statement to the world, this is going to be my obituary,’” he says of “Loser” and the “kind of disturbing” reaction that thrust him into fame. “But in a way, sometimes when you’re making music, you’re a conduit for what’s in the air. So that’s what came out, and that’s what people responded to. It’s a weird song. It wasn’t explicitly commercial. That’s the strongest thing about it. It’s like, ‘Whoa, this song is popular, and pretty much anyone could write this.’”

He said the same in 1994: “It’s pretty funny, if you ask me. It kinda seems like anybody can just get up and make a racket these days. Anything goes now, I guess.” Or in other words: “Give yourself a call / Let your bottom dollars fall / Throwin’ your two bit cares down the drain.”