In Praise of a Derelict Teen Sanctuary

How one ’90s kid found herself slightly off to the side, looking in

There’s a particular kind of longing that comes with being too young to drive but old enough to desperately want to be somewhere other than where you are. The longing is outsized when you live in a place where, even with the luxury of a ride, you are hard-pressed to think of a place to go that is not the mall or somebody’s unfinished, TV-lit basement. Some days, during this unimaginably long stretch of adolescence, I’d walk 40 minutes along the divided highway to a CVS, just to make a call on their payphone.

It was during this era that my friends and I discovered a place called the Teen Center, a scrappy, under-21 hangout that operated out of a derelict police station. Having nothing better to do with the space, the town had offered it to some local moms in the late 1980s as a place for their kids to hopefully not do drugs. Half a decade later it had become synonymous with a series of neon flyers that circulated the usual bulletin boards, advertising something called “teen night,” which sounded to us like the social equivalent of an after-school special. When in the history of teenagers has the word “teen” indicated something worth participating in? Despite its wholly unappealing terminology, a group of us ventured there one Friday night, likely out of vast, agonizing boredom.

We walked on the shoulders of our small Connecticut town’s narrow rural roads, singing Alanis Morissette loud enough to make every dog bark along the way. We were a cloud of ringer tees and drawstring backpacks and low top Chuck Taylors that let the spring rain into their every pore.

The Teen Center was oddly sandwiched on a busy commercial strip between a Valero gas station and a store that sold patio furniture. It looked like an abandoned house and stuck out strangely among the neon lights of commerce. I’d likely driven past it a thousand times and never noticed. Our town was dotted with the vestiges of other eras, rural outposts that would soon be washed away by a relentless tide of box stores.

On the inside, the Teen Center resembled what production designers create when tasked with constructing a rundown, suburban drug den: missing ceiling tiles, threadbare carpet peeling from the staircase, graffiti covering every wall. Dimly lit by primary-colored par can lights and the glowing facades of vending machines, the main floor had a pool table, some pinball machines, and a 10-disc stereo system usually blasting something popular but tolerable. Upstairs there were a half dozen dusty, second-hand couches, each waiting to become a surface upon which someone is unintentionally impregnated.

For a five-dollar cover you could go to the Teen Center and just… hang. This sounds boring, but the pull to be somewhere new or different was strong. Plus the rich kids wouldn’t be caught dead there, which meant the space was free from the hierarchies that defined most of us during the school week. We were the social dregs of our high school, the kids who had single moms and paid for their school meals with free-lunch tickets. To the spectator, it may have looked pathetic that all the town could offer its teens was an abandoned building in disrepair, but we embraced it the way a small child finds value in a discarded toilet paper roll. By way of existing, the Teen Center exuded a kind of delicious irony that pleased us: give the dregs the space they deserve.

I can now see that it served us by virtue of its ruin: It was our grungy den of iniquity.

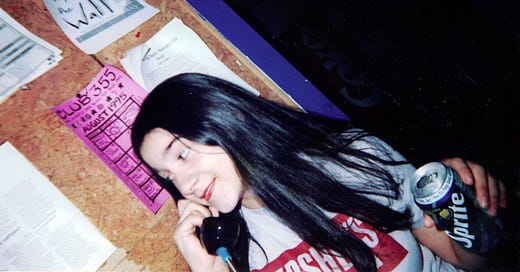

Fifteen or 20 of us began showing up every Friday night to drink Sprites and fumble around each other, testing the opposite—or same—sex for responses. It was kind of like a school dance but with fewer chaperones. A brash Italian American woman named Anne Marie collected our money at the door and patrolled the place for “funny business,” which I think mostly meant making out or smoking schwag on the fire escape. Anne Marie was probably 27 but could have been 40 or 70 for all we knew, an anonymous authority figure hovering in the no man’s land of adulthood. Sometimes she would order a couple pizzas, and we’d devour them like the voracious teenagers on snack commercials. It was a public, social space that demanded nothing of us and offered a rare, fleeting echo of our particular moment. We hadn’t had that since the great roller rink extinction of 1989.

It went on like this for a while, long enough for Anne Marie to familiarize herself with our names and the snippets of our personalities we’d let slip. Someone had a birthday party there, then a Halloween party. On Thursdays they hosted a game of D&D, but that wasn’t my friends’ thing. We were into Pearl Jam and Elastica and identified hard with Angela Chase from My So-Called Life, meaning, we spent our lives waiting for our lives to happen.

As time passed our pants got baggier, our eyeliner darker, our backpacks more obscured by patches. Eventually, the local bands arrived. Most of them came from Milford, the marginally more urban municipality next door. Milford had a public transit system and a stop on the Metro North Railroad to New York City, which I guess made it seem more cultured, or at least connected to something more significant.

When the Teen Center started hosting band nights, the space suddenly filled with Milford kids, who seemed cooler than us in every way. They rode skateboards and made zines and had part time jobs in the mall food court. At face value we may have appeared similar, but Milford kids had an urban scrappiness that even the poorest of us sub-rural specimens couldn’t claim.

Their bands had names like Miss Nancy and Seven Rounds of Space Doo-Doo Pistols. They mostly played a kind of hardcore-punk hybrid, which I wasn’t really into but pretended to be. I didn’t ask if my friends were into it. We’d stand in the crowd and headbang appropriately, looking interested. We were mostly interested in the boys, sweaty and slightly older creatures whose scent made us dig our bitten fingernails into each other’s forearms. We studied the way their bodies moved, waiting patiently for that glimpse of exposed abdomen when they jumped with the music. We each chose a boy at random to latch onto, as though picking a racehorse based on its catchy name. (It was an unspoken code, of course, that none of us would choose the same boy.)

Mine was called Ben, the singer for The Kowalskis. He looked a bit like Ewan McGregor circa Trainspotting. Ben’s phone number spelled out the phrase TRUCK 19. When I overheard him giving it out to people, I could tell he thought this made him a goddam treasure, but I called him anyway to say I thought The Kowalskis were really good. That was an unresearched hypothesis.

We talked a few times, but nothing came of it. I found out he was going out with a girl from my high school who never let anyone forget that she’d once been a child actor with a minor role in a John Candy movie. She was rich and blond and never came to the Teen Center. I don’t know how they met but wasn’t surprised that she’d snatched him up, the same way the rich kids had begun to snag all the good finds at the salvation army thrift store.

On band nights the space filled with what seemed like hundreds of kids. If there was a maximum capacity no one cared to enforce it—not even Anne Marie, who otherwise wasn’t afraid to tell kids to get the fuck out if they rubbed her the wrong way. The police were called about the occasional fight, but for the most part we were left alone to move in our throngs, packing into the main room when a band was playing and spilling out to the parking lot between sets.

Kids climbed the fire escape, scaled the roof, and fooled around on the fuck couches. The bands smoked joints behind the dumpsters with girls whose belly button rings gleamed in the yellow light of streetlamps. My friends and I longingly watched it all unfold from the safety of our invisibility. It felt as though we were glimpsing a version of adolescence that was just outside our reach, one in which people acted instead of reflected, pursued instead of pined for—the inverse of Angela on My So-Called Life. I would later play in bands and kiss people and do stupid shit I could get arrested for, but I’m not sure it ever looked as good as it did on those kids.

Shortly after I turned 16, the town decided to demolish its ramshackle police station to build a shiny new station for the volunteer fire department: an inevitability, I suppose. We protested, but a handful of scrappy teens is no match for a team of volunteer firefighters.

Uncoupled from its original location, the Teen Center briefly lived on as a nomadic entity, hosting its band nights in the brightly lit auditoriums of community centers before eventually, many years after my adolescence, taking up residence in a building that used to be a duck pin bowling alley. While the current iteration does still host bands, it also has a snack bar and a basketball court and a room full of computers. It is the obvious result of strategically planned resources instead of an incidental space that barely transcended neglect.

For the original location’s last event, we wore our favorite band tee shirts and put drugstore barrettes in our hair. We walked our usual route, passing a shitty joint back and forth and narrating the evolving levels of our buzz. When we got there our band boys were already leaving. They were over it, off to someone’s house party in a different universe. We slunk through the crowd, trying to find the night’s nucleus. The pressure to make the experience memorable came at us from all sides, and the force illuminated a severance inside me, a separating of self in two: one in the moment and one watching the moment unfold. I was high, sure, but I was also beginning to embrace my role as an observer and not a doer.

One of the only things I remember about the night is slipping outside at some point and sitting with my back against the patio furniture emporium. A constellation of kids stood in the parking lot, blowing cigarette smoke into the October darkness. From there I could see it: the ending of an era, the sliver of a generation, the fleeting of our adolescence. I pulled a notepad out of my backpack and wrote a poem. It was awful and self-indulgent in all the appropriate 16-year-old ways, but I’d found where I fit: slightly off to the side, looking in.

I love how small town communities will figure out some way to save the kids from the boredom of small towns. The grownups DO understand it turns out.....

Wow. Makes me nostalgic for my blacked out 90s youth. Reminds me of a placed called the Cobalt Cafe in the Canoga Park neighborhood of the San Fernando Valley. Doesn't exist anymore.