Lollapalooza: The First Show of the First Tour

Reliving the 1991 launch of a history making freak show

Before Coachella, before Bonnaroo, Warped Tour, and Pickathon, there was a crazy idea for a festival that combined art, activism, and underground music, called Lollapalooza. This festival didn’t take place in one location across one or two days, like Woodstock or Reading Festival. It distinguished itself in 1991 by taking seven bands to 26 cities for nearly six weeks—that’s 4.3 cities per week—and many of those were underground bands that had yet to get a big platform in the United States. These were the cool bands, the college radio bands you didn’t hear on FM stations yet and that attendees would eventually be able to say “I saw them before they were big!” And Lollapalooza did this right at that pivotal lucky moment when alternative music was crossing from the underground into the mainstream. However watered down and corporatized subsequent tours became, in the words of Jane’s Addiction’s manager, Tom Atencio: “The only real Lollapalooza was the first one. I think that was the genius one where you really had an eclectic mix of counterculture. Not a single cheese band on the bill. There was no crass commercialism them. It was fun. Thankfully, we also made a shitload of money.” Decades later, rock festivals have become a dime-a-dozen, it’s hard to gauge how groundbreaking this traveling freak show was in 1991, but as Spin said, it “changed the trajectory of the ’90s” and became “the template for what became the modern American festival.”

1991 was a pivotal year. It was to rock what 1957 was to jazz, and 1984 was to pop. By 1990, the five-year-old Jane’s Addiction had paved the way for innovative underground rock bands to work with major labels to reach a wider audience, just as Pixies and Sonic Youth did. But by 1990, Jane’s was dissolving. Guitarist Dave Navarro and singer Perry Farrell couldn’t stand each other. Perry and bassist Eric Avery barely spoke to each other, and they’d started the band. Spin called it a tailspin. “‘Tailspin’ is accurate,” said Navarro. The members were fried. As Jane’s planned their farewell tour as the headliners of this crazy festival, Nirvana was recording Nevermind. The first Lollapalooza tour started in July 1991. Nevermind came out in September 1991, after Lollapalooza wrapped up in Seattle that August. By October, Jane’s had broken up, and Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” had put underground music in so many consumers’ faces that it made them the biggest alternative band in the world and put the term “alternative music” into the American lexicon. Behind the scenes, Lollapalooza’s organizers were discussing what Lollapalooza’s second tour should look like, since it was perfectly positioned to sell more culture to the same hungry audience they helped create.

Lollapalooza gets deserved credit for its influence, but it had plenty of predecessors to model itself after. Jazz has had the Newport Jazz Festival since 1954, but the Woodstock and the Isle of Wright festivals pioneered the rock format in the 1960s. England’s Reading Festival started stayed modern by booking punk bands alongside progressive and hard rock in the late 1970s. Glastonbury’s five-day festival is as much a part of the English identity as the pub is, and it predates Lollapalooza by twenty years, drawing up to 200,000 people to a single patch of dirt. In one form or another, Seattle has had Bumbershoot since 1973, which has grown into one of North America’s largest rock festivals and featured early Northwest legends like the U-Men and Mother Love Bone. The global, sponsorship-free All Tomorrow’s Parties Festival started in 2001, and its lineup functioned as a mix-tape curated by a different band each year. Australia debuted its Big Day Out festival in 1992 with Violent Femmes and Nirvana, and provided Lollapalooza an important blueprint. So did the lesser-known Gathering of the Tribes.

The Cult’s singer Ian Astbury and promoter Bill Graham held this two-day music and culture event in both San Francisco and Costa Mesa, California in October 1990. A year before Lollapalooza booked Ice-T alongside white alternative rock bands, Gathering of the Tribes booked Ice-T, Public Enemy, and Queen Latifah alongside Soundgarden, The Cramps, and Iggy Pop. The goal was to experiment with diverse musical styles to show, as the LA Times put it, “that diversity has a constituency.” “I knew the scene in Seattle was going to happen. Nobody believed me,” Astbury said. “Hip-hop’s going to explode as well.” By providing tents for representatives of Greenpeace, Amnesty International, Rock the Vote, and Act Up, Tribes provided Lollapalooza a blueprint for its own mix of arts and activism. This novel combination proved popular. “To the surprise of the more jaded in the crowd,” Entertainment Weekly reported, “concertgoers could be found standing in long lines to sign up for causes or simply grab pamphlets. Elsewhere they could drop by pottery and silk-screen exhibits, receive an erasable tattoo, or relive their childhood with what was billed as the world’s largest bubble-blowing machine.” Tribes set the proverbial stage for the decade. “I never got credit.” Astbury said. “We didn’t do it for the money, we did it for the community.”

It could be said that Lollapalooza was more successful because of timing, while the opposite happened for Tribes. Lolla organizers made a killing while Tribes co-founder lost $50k of his own money.

“Nobody had ever toured that many bands,” said Jane’s former manager Tom Atencio. “Lollapalooza was such a major undertaking. There was no existing infrastructure.” There was only increasing interest in selling alternative music.

What got labeled alternative rock in the 1990s dates back to the 1960s counterculture, most notably with innovative, subversive bands like the Velvet Underground and Iggy and the Stooges. But the recast idea of this supposedly distinct genre started getting popular in the late-80s and early ’90s. Commercial radio stations started changing their programing to capitalize on the trend, creating a network of FM stations playing underground bands along with so-called college radio stations like LA’s pioneering KXLU—the first station to play Jane’s Addiction—and later KROQ—pronounced K-Rock—and Seattle’s KCMU, which had already been playing this music for years and broke Beck nationally.

A few American alternative radio stations hosted large local music festivals that predated Lollapalooza. My hometown Phoenix, Arizona seems so square, but Phoenix’s big alternative AM station, KUKQ, was ahead of its time. In 1989, it began hosting its annual Q-Fest, a format that it debuted at the Big Surf water park with Red Hot Chili Peppers and Camper Van Beethoven headlining. The show drew 10,000 attendees, which is how many people the first Lolla show drew. “We maxed the place out,” KUKQ program director Jonathan L. told the Phoenix New Times. Big Surf was down the street from my house. My friends and I swam there all the time. My dad knew the guy who designed its pioneering artificial wave pool. But I missed this show. My friends and I went to the next ones.

In April 1991, KUKQ did a two-day festival at Compadre Stadium called Birthday Bash, which featured a diverse assortment of industrial music, psychedelic pop, and straight ahead rock ‘n’ roll. The lineup included: The Jellyfish, Sisters of Mercy, Drivin’ N’ Cryin’, Havana 3 A.M., Front 242, Material Issue, Royal Crescent Mob, and The Feelies. In September 1991, KUKQ did two Q-Fest nights there, too. Meat Puppets headlined a package featuring incredible bands like Pere Ubu, The Wonder Stuff, Crowded House, and Candyskins. We went for the Wonder Stuff; Pere Ubu and Meat Puppets blew me away. MTV recognized that these innovative lineups represented a national trend. “[The] two-day bash with Front 242, Havana 3 A.M. and the Sisters of Mercy that brought MTV snooping around,” the Phoenix New Times wrote. “In fact, the network’s late-night program 120 Minutes devoted an entire hour to the Phoenix festival. Jonathan hand-picked the bill, saying he used ‘purism and passion,’ rather than commercial success, as the barometer to sort rock from schlock.”

The station kept upping its game. In 1992, 16,000 people showed for the third Q-Fest, which featured Social Distortion, Rollins Band, Material Issue (again!), and The Sugarcubes—Bjork’s band before she went solo. That was an epic show at a bigger venue. In 1993, KUKQ’s consolidated, one-night event drew 15,000 attendees. By then, Lollapalooza had codified the alternative music festival and drove more fans to local alternative music festivals, just as underground music culture was breaking.

“Lollapalooza was a culmination of things,” Fishbone bassist Norwood Fisher told Spin, “as what was happening on the fringes got more and more popular.”

Perry and his Jane’s crew were paying attention, because as an underground band that made good on a major label, they lived at the center of this cultural transformation. Perry was drugged out but he was ambitious, driven, and visionary. He sought opportunities, treating music like a job and a party, and as he sang in the song “Whores,” he knew that you had to take your chances if you get ’em.

Perry wanted to go out with a bang: “I told [our booking agent] Marc, ‘I’m out of here after the tour, so let’s do something good.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘Perry, you can do whatever the fuck you want.’ And I said, ‘I’m going to hold you to that.’”

After Jane’s released their third album, Ritual de la Habitual in August 1990, they flew to England to co-headline the Reading Festival. Ritual sold over one million copies in one year. That was huge for a so-called alternative band, and Reading was a huge opportunity to increase their international fanbase. But Perry’s voice gave out after their warm-up show at a small London club, so they canceled their Reading slot. Management tried to spin it as vocal strain, telling the media that Perry “came down with laryngitis,” but Perry didn’t tow that line. “I got too fucked up,” he admitted in Brendan Mullen’s book Whores: An Oral Biography of Perry Farrell and Jane’s Addiction. “So I didn’t make it to Reading. My voice was just shot. When you’re on heroin, you can’t really sing, your voice kind of clamps down.” Even though they canceled their set, their booker Marc Geiger represented a bunch of the bands at Reading, including the Pixies and Wonder Stuff. So some of the Jane’s crew attended the venerable festival for fun, and they had an idea.

“[Drummer] Stephen Perkins and I go down to Reading,” Marc Geiger told Spin, “and we’re hanging with all the bands and having an unbelievable time, and Perkins says, ‘This is so fucking great, why don’t we do this?’ And I said, ‘That’s the idea: Let’s bring Reading to America. And that will be your farewell tour.’”

The size and vibe of Reading left a huge impression on Geiger and William Morris Agency executive Don Muller. American security guards were used to roughing up audiences. Not here. “There were 40,000 kids going crazy over the Pixies,” Geiger told The Orlando Sentinel. “The kids weren’t being hassled, and everybody was having the time of their lives.” After an incredible day at the festival, Geiger said, “we go back to the hotel, where the band is sitting around pretty depressed, and said, ‘Man, you should have seen this. This is what we should try to do with the breakup tour.’ Perry said, ‘Absolutely,’ and we sat in the lobby sketching out the format and making lists of bands.”

“Marc brought the idea up of why don’t we invite a bunch of our friends to play on the American leg of the tour and try to create something like a Reading Festival, but take it on the road?” said Jane’s tour manager Ted Gardner. “The inspiration was a number of people, but Geiger was really the seed-planter. I thought it was a good idea and took it to Perry who watered the seed and came up with the name Lollapalooza.”

“Geiger and myself chose the bands,” Perry told Spin. “It might look like we were pooling from L.A. groups, but back in the day, L.A. was the epicenter of music.”

Well, not exactly. Geiger remembers sitting in the London hotel lobby, asking Jane’s members to suggest favorite bands to invite on the tour. “We started right there,” said Geiger. “I said, ‘Everybody pick a band. Let’s do this.’” Avery suggested Butthole Surfers. Navarro and Perry suggested Siouxsie and the Banshees. Geiger chose Nine Inch Nails. Perry picked Ice-T and his new thrash band Body Count. Perkins picked the Rollins Band.

After that, Geiger and Muller asked Perry to sketch more detailed non-musical ideas for this festival to serve as Jane’s farewell tour, folding in everything they’d seen at Reading, everything that previous festivals had done, and adding their own unique spin for the dawning alternative era. Perry eventually christened the festival demographic “the alternative nation.”

“Perry and his business people knew there was a large group of people out there—living like us—who were not represented by mass media,” said Thelonious Monster drummer Pete Weiss. “There was this huge swollen underbelly, this underground scene that had been fermenting for a decade since the early punk days that was already living like that. What Perry did with Lollapalooza was say, ‘You stick your flag up and say “Here we are” and everyone comes and rallies around the flag.’ Then they realized there’s this huge number of people willing to participate.”

“Lollapalooza became the business codification,” Tom Atencio said in Whores, “it was a consolidation, a new collective brand for many new marketing and promotional opportunities that were already out there. They just needed a credible spokesman, a PR figurehead to front the package…” They needed Perry.

“I’d call someone at 3 in the morning and say, ‘I want helium balloons surrounding the crowd,’” Perry told The Orlando Sentinel. “I’d say things like ‘We need Lollapalooza-sized burritos served in buckets—with buckets of Sprite.’ It all had to be different.”

He had so many crazy ideas: a marching band at each show; giving 10,000 attendees at each show a meal like a Krishna; spraying everyone with aromatherapy as they entered the venue, then providing different scents in different areas. “We’d tell him, ‘Look, Perry, this is outside,’” said Geiger, “‘they’re just going to dissipate!’” But that’s how Perry worked. He was a dreamer, an impractical adult with a childlike imagination and excitement that either irritated people or ignited their own excitement.

Promoter Jon Sidel told him, “Perry, you’re out of your mind, 10,000 plates, how are you going to do this?’”

“Perry always had fifty ideas,” said Warner Bros exec Steven Baker. “You’d listen to all of his incredible schemes and then pluck stuff out you felt you could actually help him with.”

“We’d have to discuss a lot of issues to figure out which were reality,” said Geiger. “Now he was saying his perfect evening touched all the senses: ears, nose, throat. He became less interested in the music and more interested in the culture and the other senses—whether it was smell, taste, or touch, and other pleasing experiences that were tangential to the music.”

“I’ve been told that I don’t always exactly see straight,” said Perry.

“There was conflict in nearly everything Perry thought,” said Geiger. “The best artists are nearly always the most out-of-touch with business reality, because it is polluting. I think it’s very difficult for somebody as creatively pure as Perry. The reality of what one can and can’t do, one’s liabilities, the intrusion of consequence was always an impediment to Perry’s artistic muse…”

But as the old saying goes: If you throw enough shit against a wall, some of it will stick.

Perry called Geiger at one in the morning saying, “Hey Marc, I got the name! Lollapalooza!”

Geiger said, “Where the fuck did you get that from?”

“I did hear the Three Stooges say it,” Perry later remembered, “but I didn’t have that in mind initially. I was flipping through the dictionary, and the definition of lollapalooza was something or someone great and/or wonderful. And definition two: a giant swirling lollipop.”

Perry was bored. Planning a farewell tour provided excitement, especially if he could turn the tour into a traveling party. “He was always like a party host,” Eric Avery told me, “and that’s what made him amazing when we were young, because he was toasting and bringing everybody into the party. That really is intrinsically who he is.”

“I like having a good time and being flamboyant and I like to throw parties,” Perry said in Whores, “that’s my forte.” Lolla was many things. By design it was an amalgamation. For Perry, it was also a giant party. He’d organized concerts as parties since Jane’s earliest days. Navarro and Perkins’ first show with the band was literally a party at a rented Silver Lake warehouse with a hot dog cart, smoke machines, a dance review, and a motorcycle exhibit. Barely anyone showed. Lolla came from the same place, except 10,000 people showed up at each event.

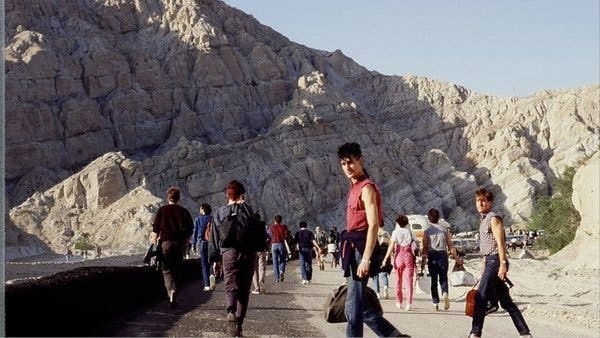

Remember, Perry had seen a lot of shows. He’d been an active part of Los Angeles’ underground music community during the 1980s, both as a listener and a musician. In January 1985, his first band Psi-Com played in the Mojave Desert with Sonic Youth and the Meat Puppets at the Gila Monster Jamboree, part of a string of 1980s guerilla art shows at what the founders called Desolation Center. Desolation Center’s co-founder Stuart Swezey booked post-punk bands like the Minutemen and Savage Republic in L.A. While driving through the Sonoran Desert listening to music, Swezey had a revelation: Why not take this music and put it into the desert as opposed to in a nightclub, which always just felt wrong? Those sorts of truly punk, DIY experiences leave a mark on people. They show you that anything is possible, especially with imagination and music industry support that Perry had. Perry roomed with Swezey and worked for his brother back in the day, building stages and doing what passed for security at some underground shows. “He always cites it as being his inspiration,” Swezey told KCET. “It’s where he learned about promoting, and all this stuff like that.” Hell, even one of Coachella’s co-founders went to Desolation Center shows. But Perry was different. He was charismatic. He was provocative, compelling to look at and hard not to listen to. And he was connected. “Perry was very lucky he had people around him like Don [Muller] and Marc [Geiger] on the agency side who so totally loved and believed in him,” said Steve Baker. But Perry was only the most obvious piece of the Lollapalooza puzzle.

Legit outlets like Spin carried the PR line to the public, calling the tour “the brainchild of Perry Ferrell and Marc Geiger,” and Perry gets—and freely takes—the credit for this festival as “his,” but the details were as much the product of his wild imagination as the basic concept was the collective brainchild of Perkins, Gardner, Geiger, and Muller. Perry just made the perfect spokesman—the famous, quotable, freak face of the alternative music world who ’90s kids respected and whose image embodied this festival enough that he could sell it to the world.

“Perry called me one day strung out of his brain,” said Sidel. “He was going on and on, super high talk. He was editing Gift and he was like ‘Dude I wanna meet with you. I got this idea and it’s kinda like [my club] Power Tools, and I’m calling it Lollapalooza, and it’s like I wanna do this fucking circus review thing, and I want you to do it with me.’ I thought he was out of his tree, but I guess he obviously wasn’t. I was like, ‘Perry, call me back later.’”

“Punk rock couldn’t last,” Perry told Spin, “only because their attitude was ‘Fuck everything.’ Mine is ‘Include everything.’” So they did.

The lineup was epic. MTV’s Kurt Loder called it “a package of acts whose only common characteristics are intensity and attitude.”

“We were hoping to kill hair bands and MTV,” Geiger said. “Get the crappy music out and the good music in.”

“When you look at that lineup, nobody was a stadium draw at that point. We certainly couldn’t have done that kind of draw that Lollapalooza did,” Avery said in Whores. “Lollapalooza was able to transcend the sum of its parts. That was the idea.”

Lolla proved both a commercial success and a blast, for the audience and the bands. That’s why Spin put the first Lollapalooza tour at the top of its list of “The 35 Greatest Concerts of the Last 35 Years,” where it beat the 2007 Led Zeppelin “reunion,” 2Pac and Biggie at Madison Square Garden in 1993, and Tom Petty’s final show. I was there. I agree.

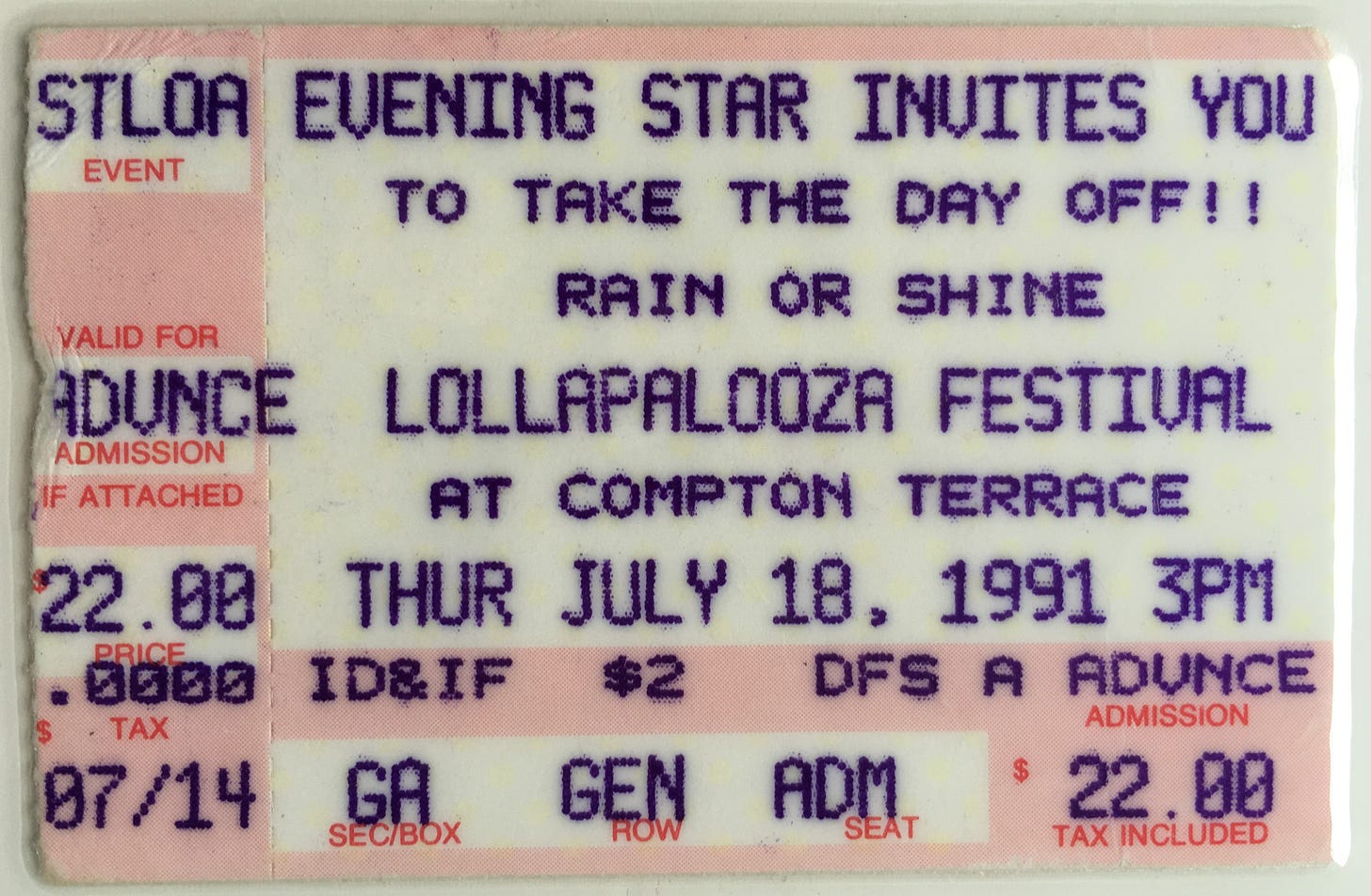

For some reason, Lollapalooza’s first tour started in Phoenix, Arizona.

Of all the cities that organizers could have debuted what became one of rock’s most influential, memorable tours, they didn’t choose New York or San Francisco. They didn’t go hip and small, like Minneapolis or Austin. They came to the Valley of the Sun, my flat sprawling hometown in the middle of July. It wasn’t because Perry loved Phoenix. Even though we boasted Stevie Nicks and the Meat Puppets as natives, if anyone thought Phoenix was cool, I hadn’t met them. And why July? The daytime temperature reached upwards of 111 degrees on this particular day. Our hottest day was 122, but anything over 110 was standard mid-summer. This bit of luck probably had to do with the way available dates at each venue helped create the map of the tour across time. “Well,” Perry joked to MTV, “it was my plan to get all the opening acts complete heat prostration and then we come in and clean up.” Whatever the reason, we were grateful. This show felt like the start of something.

My friends and I loved Jane’s Addiction and Butthole Surfers, and Nine Inch Nails’ debut album hit us like a revelation. Even if every other band sucked, attendance was a no-brainer: This was Jane’s last tour. And what else did we teenagers have to do on a summer day? All we did was skate, eat pizza, and play video games at the mall. For once, we got to the show early. We refused to miss anything.

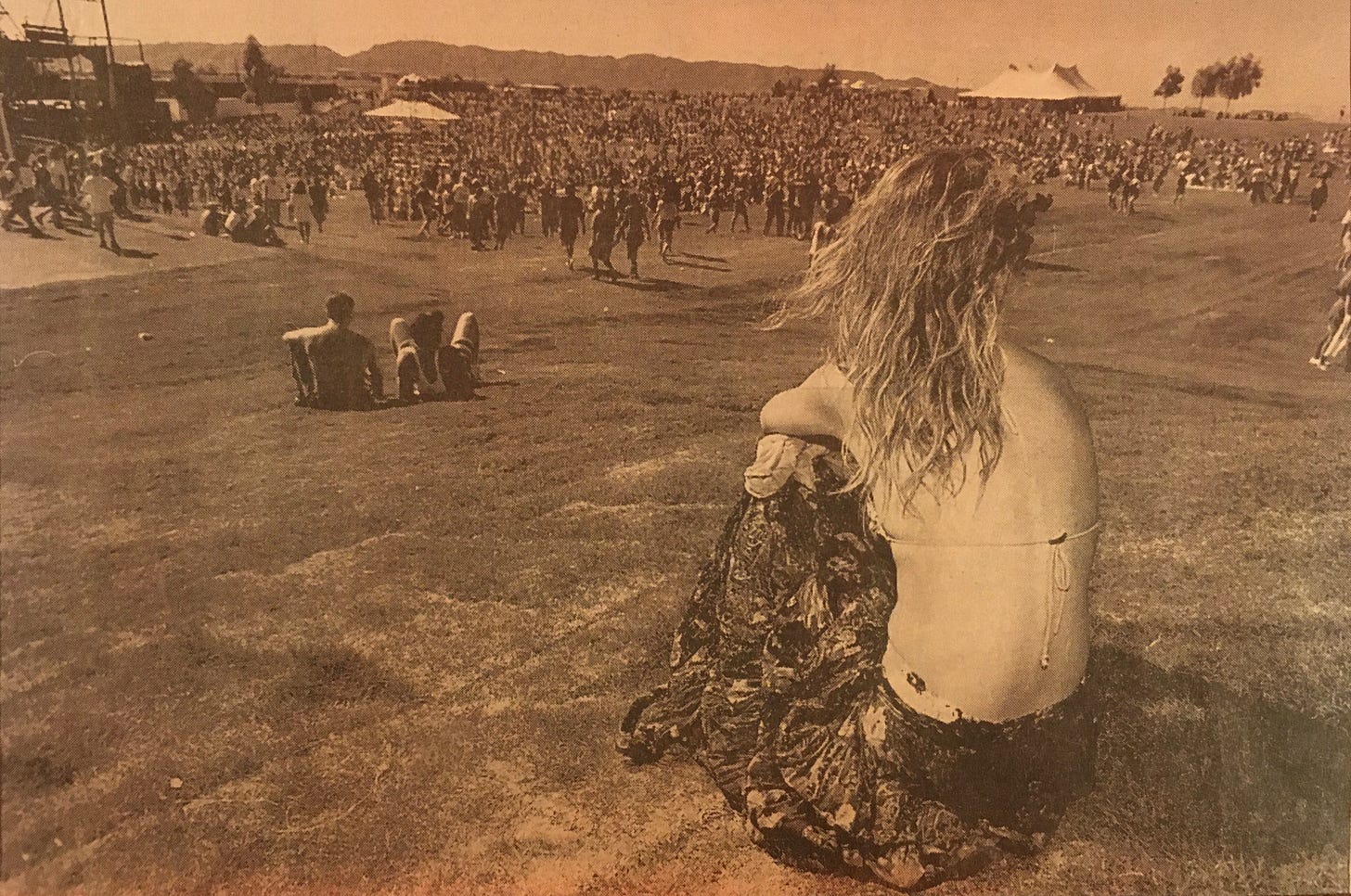

Compton Terrace opened at noon—near peak desert heat. With the sun at its zenith, the shadows were at their shortest. The venue was just grass, completely treeless. The only shade was behind the row of portable toilets and inside the one tent that organizers provided activists groups. We were left to stand around in the sun. It was brutal.

10,000 people eventually showed up, but when we arrived, the place was downright empty. The Arizona Republic’s pop columnist Salvatore Caputo’s published an account that paints a bleak picture: “Early arrivals clumped against the fence separating the lawn from the reserve seats.” Rollins Band didn’t start till 1, so we walked around. “The festival aspect of the show amounted mostly to one large tent that contained information booths for such political activists as Greenpeace and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals,” wrote Caputo. “People approaching the entrance to the amphitheater, in the Gila River Indian Community, were handed fliers by members of Rock the Vote, an anti-censorship group that urges rock listeners to register to vote.” We looked at the booth that included a Rock the Vote representative, and I grabbed some postcards. I might have only been 16, too young to register, but activism was an important part of the package, and I was all in.

Warners promotion staffer Paul V. said in Whores. “Perry thought, OK, if my name and my band can get 20,000 people here, maybe I can inspire a hundred of them to go vote or twenty of them to join Greenpeace or whatever is was that he believed in.”

“Farrell intended Lollapalooza to blend art and activism,” Spin wrote, “presenting the full spectrum of opposing viewpoints, from the ACLU to the KKK. Things didn’t pan out that way in the festival’s first year, but nascent organizations such as the Surfrider Foundation and Rock the Vote, among others, did gain national exposure.”

Navarro: “Instead of a Budweiser tent and a Nokia tent, it was local artists.”

Farrell: “Amok Books was a really progressive bookstore in L.A. Their books were really hedonistic and interesting, so we took them out on the road with us. Because I thought people should read — my people should read.”

Kevin Hanley, from Amok Books: “We carried everything from French theory to bomb-making manuals, snuff films to Tom of Finland gay-porn comics. It was pre-Internet; there was no way to get your hands on this stuff.”

That was the idea anyway.

“[The art and politics booths] were pretty pitiful, but it would have been hard to organize something like that and get high quality,” Butthole Surfers singer Gibby Haynes told Spin in October 1991. “You’d have to pay some really smart person a lot of money.”

Spin’s oral history was illuminating, and it give me a great sense of the festival’s inner workings, which complemented our experience of it as excited fans:

Eric Avery: “There was a good amount of naïveté in ’91. Lollapalooza was an experiment. I know I like Siouxsie and the Banshees and the Butthole Surfers and Ice-T, but who the fuck else does?”

Gibby Haynes: “People in the industry didn’t really have confidence in it. Perry knew it would work out. I knew it would work out.”

Booker Missy Worth: “Everybody was in it together because we wanted to prove that we were smarter than everyone else, that the alternative could be the mainstream but stay alternative.”

Backstage after his set that day in Phoenix, Lollapalooza’s inaugural rapper Ice-T saw the future. “I know this is gonna be a tour people are gonna talk about for a long time,” he told MTV. He was right.

“It was quite a big show from a public standpoint,” stage manager Michael “Curly” Jobson told Spin, “but production-wise it was relatively small—the fact that it wasn’t a slick, overproduced event gave it that element of cool. Lollapalooza was a little ramshackle errand.”

At 1 p.m., Rollins Band started the concert.

Shirtless, shoeless, wearing nothing but black gym shorts, singer Henry Rollins positioned himself at the center of the big bright stage and greeted the thin crowd. Between 1981 and 1986 he’d fronted Black Flag, one of punk rock’s most influential bands, but this was his new band, his own band, and they’d been tasked with not only starting the show, but essentially launching the entire Lollapalooza tour, and what became a cultural institution. Rollins did the trick. The band’s intensity grabbed the crowd’s attention and distracted from the heat. The sweaty Rollins talked and screamed and howled into the mic, squatting with the mic in his hand like he was doing squats in a gym, moving up and down like some kind of hunting spider, staring in a trance before belting out philosophical declarations and self-examinations like: “I’ll love you and hate you both at the same time / Heal you and hurt you and laugh as you cry!” After the set, it felt like we’d been through Primal Scream therapy followed by a punched in the face.

When they left the stage, my dizzy friends and I sat in the sun in the treeless field watching people and waiting for Butthole Surfers, or as many newspapers called them: the B***hole Surfers.

While the tour was figuring itself out at this debut show, we attendees were trying to figure out the tour. It’s amusing to read the Arizona Republic’s stiff pop critic’s description of the audience: “There were punk rockers in high spiked hairdos and mohawks. There were people dressed in clownlike makeup. Others looked relatively collegiate. Also, some skateboarders with their turned-around baseball caps and baggy shorts. And countless young women dressed all in black with their hair dyed red and their lipstick a similar shade.” Sounds right. And sounds like he wrote that from an elevated hunting blind while observing through binoculars.

MTV was there to cover this historic experiment, with MTV’s 120 Minutes host Dave Kendell prowling around the crowd doing little location spots from inside the sweaty audience. We recognized the British host from MTV, and that was a rare brush with a mainstream celebrity. At one point during the day, Kendell stood behind us doing a spot. “It’s a hundred and nine degrees,” Kendell told the camera, “but Arizonans have shown up in force for the opening date of Lollapalooza, not only one of America’s greatest ever and most diverse line ups of alternative rock, but also a touring carnival of music, information, and art.” The broadcast aired a week after the show. I recorded it on a VHS tape that I watched repeatedly, marveling at the tiny bits of concert footage and hoping that more footage would surface one day. You can hear some dude howling off camera, looking to disrupt the proceedings and get himself on TV. My crew wasn’t close enough to get in the shot, but lord knows I would’ve photo-bombed it if I could, 30 years before there was a term for that kind of adolescent disruption. Undeterred, Kendell told the world: “Lollapalooza could be the tour of the summer.”

When Butthole Surfers took the stage at 3, barely anyone was up front. Some people sat in their hot metal chairs in the small reserve section, but the grassy general admission area on the stage’s left side was essentially empty, so I stood there and watched. No pit. Few people around me. The heat kept it roomy. My friends hung back. It didn’t slow the band down. Playing their wild show to a handful of people in the middle of the day in a field with no shade wouldn’t seem like optimal Butthole Surfers conditions, but they were incredible. The stage was too big for a band like them, so Gibby roamed around, like a drunk lion stalking his next prey to provoke and confound. Wearing a black vest over his bare sweat-soaked chest, he cracked Budweiser after Budweiser. He’d turn dials on his sound effects machine. Then he’d stand there holding a Bud in one hand, the mic stand in the other, and scream through the bullhorn that had become one of his signatures. When he sang, he was in full control, and his demented stage persona was the center of attention. Butthole were one of the most original and inaccessible bands from the ’90s, and they managed to look so terrifying—so alien—in the white light of day. You either loved them or hated them, and even us fans couldn’t completely figure them out. Confusion was part of their charm, like listening to an acid trip. Some of us like that. They were so captivating I almost forgot about being on the cusp of heatstroke.

Gibby remembered the show. “That place was just a flat, thankless expanse of land. Fucking miserable.” Even to a Texan, our venue seemed desolate.

At a certain point on the Lollapalooza tour, Gibby started shooting blanks from a shotgun and taunting the audience. Spin:

Haynes: “I don’t know who said it — it might have been Duchamp — but someone said there’s nothing more surrealistic than firing a blank gun into a crowd of people.”

Henry Rollins: “It was full of rounds with no shot, just powder. And he would yell into the microphone, “I didn’t see you people moving when the Rollins Band played, you sons of bitches!” And he would cock the shotgun, and aim it directly into the audience and shoot it.”

Norwood Fish: I was like, “What the fuck!”

If he did at our show, I don’t remember. The volume of beer he drank while signing through that bullhorn was memorable enough.

Haynes: “Whatever band was onstage, we would walk into their dressing room and drink their beer and try on their clothes and shit. We’d always take the Banshees’ deli tray and say that we took Siouxsie and the band’s cheese.”

Budgie: “[Butthole Surfers’] dressing room was empty apart from beer. [The tour] was pretty much partying from day one. Ice-T’s bus was a constant up and down movement.”

Unbeknownst to us, the heat was driving organizers nuts behind the scenes.

“It was so hot you couldn’t even put your hand on the steel the stage was constructed from,” said stage manager Michael “Curly” Jobson. “And we’re in some rodeo shithole in Arizona. Someone really thought that one out.”

“Everybody backstage was in a bad mood and pissed off,” photographer Chris Cuffaro said in Whores. “The heat was just nasty. It was just too damned hot.”

“We were getting in fistfights amongst ourselves on how to treat the audience,” said Tom Atencio. “Should there be misting tents? Should there not be misting tents? Because it’s 114 fucking degrees in the middle of the desert. Some people said that misting tents would make people go into shock. Others were saying, ‘Are you fucking nuts….of course you’ve got to get water and shelter!’”

They set up a janky shower where people could cool themselves off. During the Butthole Surfers, someone started hosing down the audience with water, which was nice. With such fast evaporation rates, these were short-term solutions, although welcome.

Again, Caputo: “Here [along the fence by the reserved section] fans ‘moshed’ in small clusters and awaited some relief from the heat which came from water hoses from the stage area. Although more rugged individuals were dancing in the early going, the crowd seemed subdued.” As hot as I was, I’m more of a cat: I didn’t like being wet. I’d rather be hot and dry than wearing soaked cotton clothes. I avoided the hoses.

At 4 p.m., still hot as fuck, rapper and subsequent actor Ice-T and his metal band Body Count took the stage. “I’m here to prove to you that rock ‘n’ roll is not a black thing or a white thing,” T told the crowd, “but a music thing.” Caputo finally got something right when he took T’s statement as the festival’s “statement of purpose.” Blurring genres and blending audiences was one of the festival’s primary goals.

“A lot of white kids will not go to a black show,” Lollapalooza producer Ted Gardener told Time in 1993. “They’ll buy the records, but they won’t go see the band. They’re afraid they might get killed. And some black kids feel the same way about white shows. Our attempt is to try to bring new styles of music together.”

Rapping then headbanging then rapping some more, Body Count did just that. And they owned the crowd.

“People were ready for something different, something that pushed them a little outside of their comfort zone,” Eric Avery told Spin. “Like a reason to come out and see live music.”

At 5 p.m. NIN took the stage. My friends and I were so excited that we went so close to the stage that it was disorienting.

“And here come Nine Inch Nails,” remembered Zelisko, “walking up all in black and chains and safety pins. Pretty dark for the middle of the afternoon in Arizona.”

NIN was just breaking, and we were addicted to their debut album Pretty Hate Machine. We stared up from the front of the stage, our teenage eyes glued to these pasty-skinned goths dressed with a touch of Edward Scissorhands.

They ripped through an introductory song called “Now I’m Nothing” and got partway through their second, “Terrible Lies,” before their equipment malfunctioned.

“You use electronic equipment and you don’t have direct cooling for it and we’re doing a show in 115-degree heat,” said Jobson, “what’s going to happen?”

I was too excited to hear that anything was off, but the failing sound enraged front-man Trent Reznor so badly that he kicked over his keyboard and amp and stormed off stage. My friends and I looked at each other, wondering what that was about. Turns out, the Arizona heat had damaged the band’s sequencers.

“This power cable—a $15 thing called a quad box—kept short-circuiting and would shut everything off,” said Nine Inch Nails guitarist Richard Patrick. “Here we are, first show on the most important tour of our lives, and this whole thing goes down in a nightmare. So we trashed the stage and went on our crazy little punk-industrial rampage and stormed off. Blamed everybody, but it was really just one bad cable.”

This was the biggest show NIN had ever played at that point, and those expectations, coupled with the extreme heat, put everyone on a knife’s edge. The crew backstage was trying to diagnose the problem, and they believed they’d fixed it. After a few tense, confusing minutes, NIN reemerged and resumed their set, but part-way through “Sin,” their third song, the equipment failed again, and Reznor slammed down his mic and turned to the stacked amps, pushing them back and forth until they toppled over, and jumping on top of what had fallen over. Patrick’s guitar flew through the air and slammed against the stage. And they left, this time for good. Fans were pissed.

“No way!” people yelled. “Fuck you!” We waited there by the stage, hoping they’d try again, but they never did. NIN’s set was over. We got less than three songs from one of our favorite bands. We had no idea what happened.

As crew dismantled NIN’s stuff, Ice-T told some kids up front: “I guess what happened: Nine Inch was jammin’, and Trent started trippin’.” He made circles around his temples like Reznor was nuts.

Backstage, Reznor explained to MTV: “We couldn’t play because one of the power boxes had melted, and every time the low end of the PA would rumble, it would jiggle the cord and all power onstage would just shut off and turn back on. If you have a sampler, that means you’re down for a minute. And if you have a tape deck, ahem, that means it stops.” Between sets, some managerial dude with really bad hair apologized to the audience for NIN leaving early.

At 6:15, the band Living Colour started a blazing set during the last hours of blazing sun. Anyone who didn’t know their music left the show as a fan. They had the kind of energy and musical chops that required a big stage to hold it. And the audience ate it up.

Although the band had won two Grammys the previous year, one for their song “Cult of Personality,” and one for their second album Time’s Up, they weren’t widely known. Blending metal, punk, funk, hip-hop, Blues, and jazz into an energetic rock fusion that went by the name funk metal, they were one of the few rock bands at the time comprised solely of people of color, and they had the kind of stage presence and mainstream chart-topping success that Caucasian rock bands could only dream about.

Even though Black rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t that conspicuous, it had a long history. In the 1960s there had been the psychedelic rock band Love, led by Arthur Lee, which was one of America’s first racially diverse rock bands. There was Michigan’s short-lived Black proto-punk band Death. In the early 80’s, Bad Brains had started mixing punk and reggae in D.C., and influenced scores of musicians. There was Fishbone, who were so genre-spanning and inventive that they still defy classification. There was the South Bronx’s 24-7 Spyz, who shared a style with Red Hot Chili Peppers, yet Living Colours sound came with absolute freshness and technical virtuosity. They put on an incredible show and put Black rock ‘n’ roll in front of thousands of white faces during the summer of ’91. My friends and I had been jamming their debut Vivid. Live, we were rapt.

After their set, the sun fully set. The stars came out. Although the air stayed hot, the solar rays no longer burned through our pale, European skin.

Siouxsie & The Banshees came on at 7:45, in the blue twilight of the Arizona sky. They were incredible. Their iconic singer Siouxsie Sioux prowled the stage like a cat, strange and sinuous. Her beauty was obvious. Besides her singular voice, what captivated me most was her absolute presence. She had such personality, and her dancing entranced the audience. Backed by the Banshees’ hypnotic music, it was no wonder this band topped Navarro and Perry’s list of headliners. Even though we teenagers only knew the band from seductive radio hits like “Kiss Them for Me” and “Peek-a-Boo,” this band had been playing since 1976,and quickly transcended their post-punk origins. In the weeks following the show, I bought a few of their albums to hear more than their hits, albums I still own.

Jane’s Addiction was scheduled to take the stage at 9:15 pm. By 9, the entire audience stared in one direction, waiting for Jane’s. From my position, the anticipation was painful. My heart raced, and stomach knotted. Everyone was eager for the show to start, but once it started, the band was one step closer to its end, and no one wanted that. My friends and I debated going up front to watch. A thick crowd had gathered at the stage, and we were too heat-exhausted to make our way through the sweaty masses to get close, so we stayed in the middle of the slope behind the reserved section. We could see well from there, and I wanted to watch their performance rather than get tangled in a mess of sweat and hair.

Finally something happened. A high-pitched tribal drum banged a fast beat through the PA. The stage lights dimmed. Faint figures moved around up there, and a roar moved through the crowd. Then Avery’s baseline started. It was “Up the Beach.” Jane’s started all their shows with it now. It was one of my all-time favorite songs.

The sense of anticipation lifted, and euphoria took its place. The show I’d waited two years to see had finally started. But my first time seeing them would also be my last. How could I spend the rest of my life with only three Jane’s albums, I wondered? Why couldn’t they write one more? Smoke machines pumped white plumes that blew across the stage, and everything—the smoke, the band—got cast in a blueish purple light. Then the lights went on and there they were, the most popular alternative band in the world, the dark princes who’d helped usher in the alternative era and were about to plant the suffix –palooza into the lexicon, headlining a festival that people would talk about for decades and that had, at that moment, only existed for 9 hours.

A white spotlight illuminated Perry. Wearing a white hat and white tank-top, he clutched the mic stand with one hand and thrust a bottle of wine into the air. Behind him, Stephen Perkins pounded out the beat between a jungle of potted plants and white statues. Perkins drummed head-down, so he was just a whirling ball of curly hair. Navarro painted the night with his piercing guitar line as Avery grooved in place on the dark, opposite side of the stage. Beneath them, Perry laid the song’s only comprehensible lyric: “I’m home.” His banshee wail echoed through the field: “Home!” My friends and I looked at each other, thrilled. We were home.

One iconic bassline merged into another as they dove straight into “Whores,” the song that marked the true beginning of my love of rock ‘n’ roll.

They played their best songs one after another: “Standing in the Shower… Thinking,” “Ain’t No Right,” “Three Days,” “1%,” and “Then She Did.”

They were as intense live as they’d sounded on my bootleg recordings but hearing their music at this volume made the experience visceral, almost spiritual. It reverberated in the body. Perry shimmied and did his weird dances as he yelled lyrics out at the crowd: “He don’t like the place I’m heading / Same place he’s heading.” Navarro looked scary: dread-headed, wearing a pair of striped overalls over his shirtless chest, sunglasses on his face despite the dark night. Avery was the coolest to watch, shirtless, cutting circles while banging on his bass. How he danced, played bass, and swung his hair at different rhythms was a mystery, but you could tell he had the music in him from the way he moved his body.

To our left, MTV had their raised platform so they could film the bands play. That thrilled me: I assumed that meant we would see this all again one day, so even though Jane’s was ending, this night would live forever. I didn’t understand how TV shoots worked, how they filmed everything just to edit together selected parts, dispensing with the remaining footage. Where did all that unused footage go?

Only in 2019 did I see the full, raw Jane’s footage that someone leaked on YouTube. The scene looked just as I remembered it. As Perry sang: “Camera’s got them images, camera’s got them all. Nothing’s shocking.” MTV’s cameras didn’t capture one of the night’s highlights: Dave and Perry’s fight.

“Perry and David got into a fight onstage and it cut short our set,” Avery said in Whores. “Dave was out of his mind on Valium and shit and one of the two bumped into the other one and the other got so upset and so then they started taking runs bumping into each other. Then it turned into literally them entangled falling off the side of the stage fighting.”

I couldn’t see the fight on the side of the stage, only the initial tussle. Everyone remembers the details differently, and my memory is probably off. I remember them ramming each other shoulder-to-shoulder, then Perry wrapping his arms around Dave’s waist so the two swung around together. They twirled as Dave played guitar. It seemed playful at first. After Perry let go, Dave tossed his guitar into the crowd. The guitar disappeared among the silhouetted heads in the reserve section, and Dave stormed off-stage, pushing over his guitar stack on the way.

Things were tense.

Jane’s had exhausted themselves touring for a year straight for Ritual de lo Habitual. The band’s personal relationships were also poisoned. Perry and Dave couldn’t stand each other. Avery and Perry wouldn’t speak. Perry drank wine, smoked weed, and took acid. Eric was off dope and unhappy with life in a famous band. Dave had gone to rehab but relapsed before Lollapalooza. Without their old chemical coping strategies for getting along on touring, Perry and Avery avoided each other. Every member took the stage from a different direction. Avery often sat in the back of the tour van. While Perry was indulging in sex and intoxicants before shows, Avery did his own thing.

“We weren’t brothers,” Perry said in Whores, “we weren’t tight, we weren’t a team.”

“Dave was always in his closed dark world behind sunglasses,” said Cuffaro. “They were all in their separate little worlds. Stephen’s energy was the glue that kept it all together. Eric just came and did the shows and left. He didn’t want to be around. If you’re trying to stay clean, the last place you want to be is hanging around Jane’s Addiction backstage before a show!”

“Dave was doing three to four grams a day, sometimes more,” his cousin Johnny Navarro said in Whores. “We’re talking up to $700 dollars of dope in one day. …Dave would just shoot nonstop. He was addicted to bangin’ as much as he was to getting loaded.” Although Navarro completed rehab, he resumed using before Lollapalooza. The tour’s first day had started badly.

“The day of the show,” said Johnny Navarro, ‘Dave goes, ‘Do you have any shit?’ I’m like, ‘Well, yeah—’ I was trying to hoard for myself. I was like, ‘Yeah, aren’t you hooked up?’ Now we need to go score downtown on the fucking street so he can make it to the show. Otherwise there’s no Jane’s Addiction at Lollapalooza.”

When I started using dope years later, I would score south of downtown Phoenix as an innocuous, average looking guy. With his tattoos and dreadlocks, Navarro must have been quite a sight.

“Perry had been working very hard at putting together this Lollapalooza tour, getting all the bands together,” said Dave, “and on the very first night in Phoenix, Arizona, I was in no shape to perform.”

“I was in a testy mood,” Perry said. “Dave was sick and wanted to bail. He just didn’t want to play anymore.”

“The tension was unbelievable because the band was ending,” said Atencio. “Dave was so tender, fresh out of rehab, but we had no fucking concept of keeping people straight…he was flung headlong from rehab, straight into this grueling, vigorous tour.”

All this shit was going on while my friends and I were having the time of our lives that summer day.

The band was quitting for good reason. They couldn’t even get along on the first night of their farewell tour.

“I saw their last gig at Irvine Meadows at the end of Lollapalooza,” said Thelonious Monster singer Bob Forrest. “They were just awesome. And they weren’t even talking to each other anymore. I love things like that! Eric was standing over one way and Perry walked on another way and Dave was already on the other side. Three humans who don’t talk to each other, but as soon as they hit the opening chords of ‘Three Days’ it was magic, just unbelievable.”

Forrest had famously been in Dave’s position at the PinkPop Festival in 1993. Dependent on heroin, he had to wake up way too early and leave his dope supply in Amsterdam to perform in a different city. Heroin withdrawal led him to over-drink Jägermeister, and the performance was an infamous low point because he left abandoned the show early. Navarro secured dope and had powered through until this fight.

It just seemed too authentic to be true. Jane’s volatility had always powered the band—the sense that the band could fall apart at any time, even when the members got along—and that internal combustion was not only alive in the music. Here it was on stage, happening before our eyes.

“Perry walked off after the song was finished and they just started wailing on each other,” Cuffaro said, “punching each other out. Ted finally jumped in and broke it up. We didn’t know if they were going to come out for an encore.”

I couldn’t see Perry and Dave fighting from our angle, but while they fought, the crew stood Dave’s stacks back up in hopes of their return.

“Dave didn’t want to go back on,” Perry said in Whores, “and I felt that we should’ve given them a longer show. He said he’s not going, and I was like, “You are.” Then I picked him up—in those days, I used to watch pro wrestling—and I gave him a pretty good body slam. We ended up going back on.”

“It was a hell of a way to debut,” Andy Cirzan, vice president of Chicago’s Jam Productions, told The Chicago-Sun Times. Because Jam was producing the first Lollapalooza in Chicago’s suburbs, Cirzan flew to Phoenix to check the debut out. “The fight continued off-stage. There was some definite roundhousing going on. I don’t know if anyone landed a punch, but I specifically saw some punches flying as they left the stage.”

“Yeah, well, that’s why we were leaving,” Farrell said.

Rock ‘n’ roll is undoubtedly filled with stories of on-stage fights and internecine battles. An excellent example from that era comes from the Pixies, when singer Frank Black threw his guitar at bassist Kim Deal during a show in Stuttgart, Germany. They barely spoke after that, and like Jane’s, they finished their tour despite internal tensions, though barely. They broke up soon after.

Jane’s had another memorable show in Phoenix when they played Celebrity Theater in 1990. They had an elaborate set on that tour, crammed with dolls and plants, framed images and Santeria type candles and charms, stuffed to the gills like the cover of a Ritual. Bootleggers called the audience recording of that show “Riot in the Round,” because the circular theater’s circular stage slowly turned to provide consistent visibility throughout the venue. That design also provided fans access to the stage, which they pillaged, taking photos and doll parts back into the crowd as souvenirs. Once security cleared the stage, mitigating further damage, the band resumed the show.

During better times, Navarro and Perry used to goof around. Just look at the live 1990 footage that became the “Stop!” video. At one point Perry sings while crouched at Dave’s knee, stroking his leg while he solos. Later, Perry creeps behind Navarro and tries to de-pants him during a problematic guitar solo, and with Dave eventually kicking him off. Perry came back smiling, but by July 1991, things weren’t so playful.

At Lollapalooza, Avery and Perkins hung around on stage by themselves, seeming as confused as the audience was about what would happen next. “I was nearly clean and I was like, ‘This is the first night?’ said Avery. They eventually ducked backstage, too. A crew member went into the audience to retrieve Dave’s guitar.

We felt relieved to see Navarro strap back on his guitar again and Perry take the mic. We prayed that this would not be another truncated NIN set. But as the band played “Mountain Song”—or maybe it was “Oceansize”?—something happened. Instead of strumming, Navarro reached for Perry, trying to get ahold of him. My memory is hazy. Chris Cuffaro remembers “Dave started body-slamming Perry while he was trying to sing.” When he couldn’t take him down, a frustrated Navarro knocked over his stacks, smashed his guitar against the stage, tossed it into the crowd, and stormed off again. That wasn’t rock ‘n’ roll. It was pitiful exasperation, like a temper tantrum instead of punk rock nihilism: I quit. That made two bands in one concert who’d left prematurely.

If I remember correctly, the others finished the song without him. And that was how the first Lollapalooza ended, in a mass of toppled speakers and expectations. And that was how the legendary festival, which became the gold standard for music festivals for the next six consecutive years, began.

“Ted [Gardner] was weeping like a baby,” Tom Atencio remembered. “He was blubbering, ‘It’s all blown up in smoke, everything that I’ve been working for, for two years. The fucking tour is going into the shitter.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with losing your temper,” Perry said in Whores, “you can always make up.”

Apparently they forged a way forward.

“From that point on, everything went smooth,” Navarro said. “We didn’t necessarily iron anything out, we just got past it.”

Avery: “That’s just so…that is Jane’s Addiction right there.”

If they’d planned to close the set with songs like “Summertime Rolls” and “Chip Away,” we never got there. My friends and I looked at each other. Was that it? Everyone waited. And waited and waited. Then the lights went on, and a collective groan rose from the audience. That was it. We were disappointed, but we had to be happy with the songs we got. Time proved we got a good story, too.

The venue had an 11 p.m. curfew. The fight ensured they made that.

Jane’s tensions didn’t affect the tour’s success. Playing to over 430,000 people during its almost six-week run, this first Lollapalooza tour grossed over $10 million dollars, making it the highest-grossing concert of 1991. Just as Lolla built from past festivals, it spawned a number of so-called imitators, like Warped Tour and H.O.R.D.E. (coyly nicknamed Lollapatchouli)—and even Perry’s own ENIT festival—which hoped to capitalize on different genres, different mind-sets, and segments of the same youth demographic, to reproduce the lucrative magic. They made money, but every subsequent Lolla was more slick and less authentic than the first. For me, that July day marked the beginning of a decade we spent going to a dizzying number of concerts.

“Lollapalooza was cool,” Gibby Haynes told Spin. “A vindication, if you will. As far as musicians go, I think they value attention more than money. Instantly, managers, labels, bigger bands were pushing to get on the next year’s. When there’s a paradigm shift like that, there’s only a moment before what’s shifting gets absorbed into the bigger body.”

The first Lollapalooza tour ended in rainy Seattle five weeks after it started in Arizona. Seattle seemed a fitting end, considering that the biggest rock bands in the world were coming from that city, a city being marketed as the epicenter of the new rock ‘n’ roll by what would become the juggernaut indie label Sub Pop.

“In Seattle, me and Perry went to the [Pike Street] market where there’s tons of shops and crap,” Haynes remembered. “Perry was just shoplifting at will, taking whatever he wanted. I followed behind and managed to pay for a few of the things. He was just so blatant about it, screaming through the store with that maniacal look on his face—wide-eyed, fucking high on who knows what.” And that was the tour’s last stop. After that Jane’s played some shows in Australia and New Zealand, and played their last show in Hawaii. And that was that. The ’90s continued without them, but undeniably because of them.

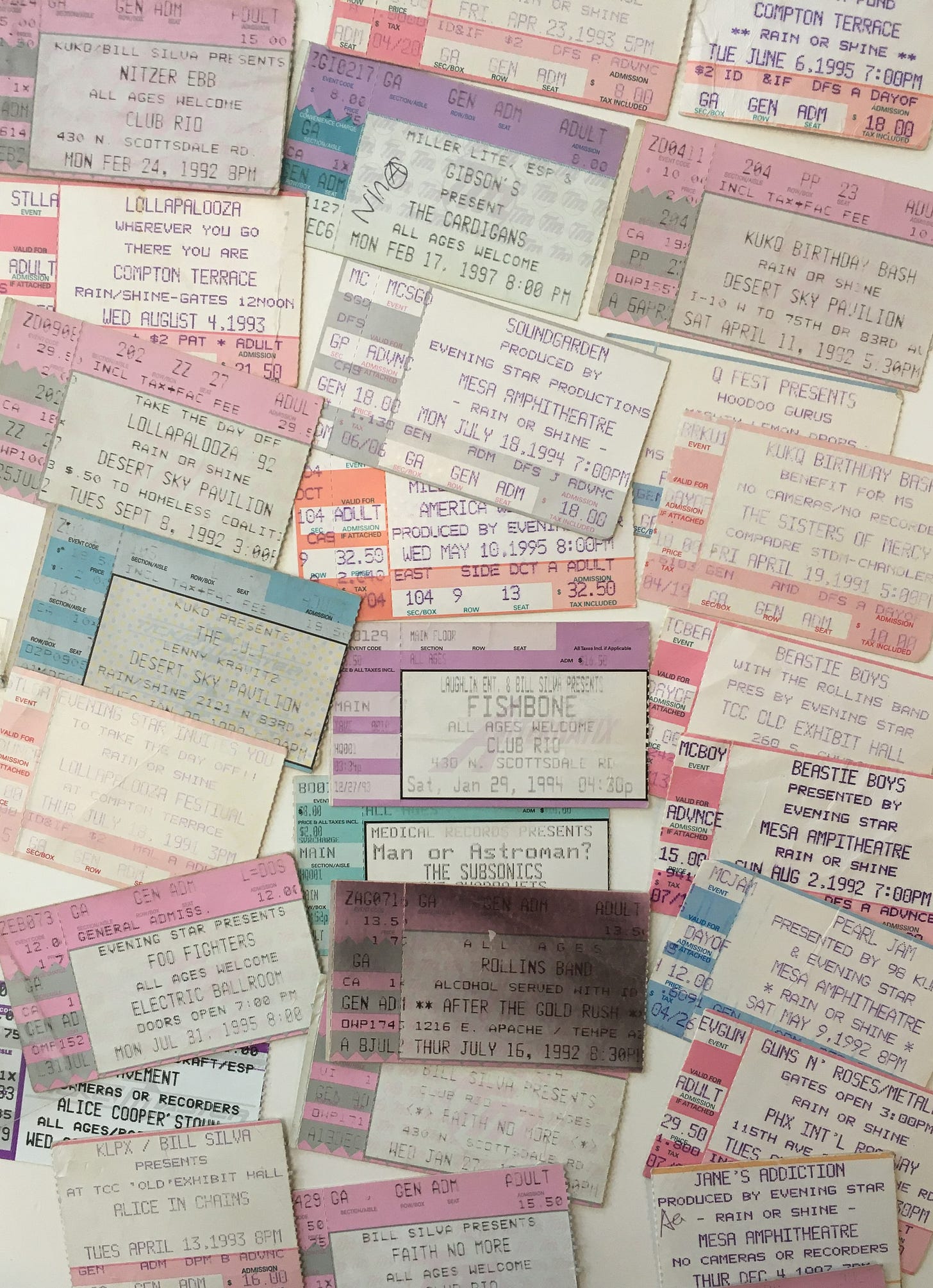

Starting in 1991, my friends and I went to as many shows as we could, because that was the year we got our driver’s licenses. Our teenager days of watching bands through the back window of Long Wong’s Hot Wings on Mill Avenue were over. We even drove a hundred miles to catch shows in Tucson, two hours to the south. My mom liked to say, “Once you got cars, we rarely saw you.” That’s because we started hanging out at other peoples’ homes, drinking beer, and crashing house parties. We didn’t need parental permission to see bands on weekends.

From 1991 to 2000, my friends and I saw: Soundgarden, L7, Fishbone, Primus, Violent Femmes, The Cramps, The Meat Puppets, The Dead Milkmen, The Jellyfish, The Wonder Stuff, The Samples, The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Cult with Lenny Kravitz, Faith No More (four times), Mr. Bungle (five times), White Zombie (one time too many), Green Day, Beastie Boys, Bad Brains, Belly, Hole, Babes In Toyland, Fugazi, The Breeders, Foo Fighters, Cypress Hill, Arrested Development, De La Soul (maybe?), House of Pain (painful), Social Distortion, Beck, Rollins Band (three times in less than two years, but Black Flag zero times, sadly), Tool opening for Rollins Band, Monster Magnet, Porno for Pyros, Alice in Chains, The Smashing Pumpkins (great band, horrible show), Temple of the Dog, The Mighty Lemon Drops, Pere Ubu, Hoodoo Gurus, Material Issue, Dramarama, The Sugarcubes before Bjork became a famous solo artist, Ministry, Front 242, The Sisters of Mercy, Nitzer Ebb, Ethyl Meatplow, Melt Banana, The Bomboras, Man or Astroman? The Subsonics, The Quadrajets, The Cardigans, Calexico, Pavement, The Dirty Three, Melt-Banana, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant, Dylan’s 1999 Blood on the Tracks Tour, Lollapalooza 2, 3, and 4, and Pearl Jam twice in 1992. Some of these shows changed my life. But because of their numbers, I wouldn’t remember some of these shows if I hadn’t saved my ticket stubs.

As my friends and I have aged, our crew pooled memories, creating a fuller memory than our hazy individual recollections could provide. Someone would remember jumping the security barrier to reach the second Lollapalooza stage. Someone else would remember how Nate got kicked out of the Mr. Bungle show for jumping off stage during the first song. Then YouTube footage would corroborate hazy memories of Temple of the Dog playing a few songs and other things that resemble inventions 30 years after we experienced them. JR remembered so many pieces of the puzzle; unfortunately, he died in 2018. After his death, I inherited the Wonder Stuff setlist that he printed on a dot-matrix printer at his dad’s Alphagraphics print shop in 1991 and framed with a scrap of paper that he managed to get the entire band to sign. Man, JR loved that band. Now in midlife, when I wish the bootleg recordings I made weren’t so shitty. It wasn’t so much about the music itself. Deep down, I still want the same feeling of exhilaration we felt in those early years of the ’90s, which was a light shining at the dawn of a new world, a time that just happened to be the beginning of our adult lives, when everything was exciting and music was our vocabulary, our familial bond, our whole lives.

“All the affection I poured into bands, into films, into actors and musicians,” musician Carrie Brownstein writes in her memoir Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl, “was about me and about my friends. …That’s why all those records from high school sound so good. It’s not that the songs were better—it’s that we were listening to them with our friends, drunk for the first time on liqueurs, touching sweaty palms, staring for hours at a poster on the wall, not grossed out by carpet or dirt or crumbled, oily bedsheets. These songs and albums were the best ones because of how huge adolescence felt then, and how nostalgia recasts it now.” No one I’ve read has said it better than Brownstein.

Even random memories like the show where Dramarama’s singer announced “So this is our last song. It’s called ‘Last Cigarette” take on a different kind of heft. His announcement turned the kids in the mosh pit aggressively rowdy and began spinning the pit hard, knocking elbows into ribcages. It’s the only song of Dramarama’s that I even knew. That moment, like that entire July day at Lollapalooza, is one more random memory from a decade of shows that compose my long weird life of music.

*Speaking of friends, I’d like to thank my long-time friend Jim Yue for his precise, thoughtful edits of this piece. We saw a lot of shows together in our youth. Who would’ve thought that one day he’d be editing something I write about them. Thanks, Jim!

Hey Aaron, this is Jonathan Zwickel, the writer who compiled the Lolla oral history for SPIN in 2011. This is a really powerful piece of writing--personal, historical, descriptive... Glad I came across it!

Yes I was. Lived in South Scottsdale. By when you write of getting your drivers license, I’m thinking I’m close to 10 years older than you. There was a place near Big Surf, too, it seems, where we’d go see bands. Seems like it was kind of secret. There was a mosh pit - seems like it was a small building. Can’t quite picture it. Lol… can remember my brother having to pull me out of that pit a couple of times. Moved to Seattle not too long after that first Lollapalooza. Been around here ever since.