“Lollapalooza ’92 is coming,” said the text beside a Rollins Band show advertisement in our alt-weekly. The anticipation had been building since the first Lollapalooza tour in 1991, and now, after a year of waiting and reminiscing, the second Lolla tour was set to roll through town.

“We naively thought this would be cool as a one-off,” Lollapalooza cofounder Ted Gardner told Spin. “We had no intention of doing it again.”

“Nothing was supposed to come of it,” cofounder Perry Farrell said. “I had no intention of doing it again. I mean, the thing was over, and William Morris and Marc and these guys are all really enthusiastic and saying, ‘We think we can get the Red Hot Chili Peppers for next year!’—and I went, ‘Wait, what? Next year?’”

The experimental music and culture tour proved too lucrative and fun to let go, so thankfully, organizers did it again in the summer of 1992. Like we had the first time, my friends and I went to that show, too.

I was 17.

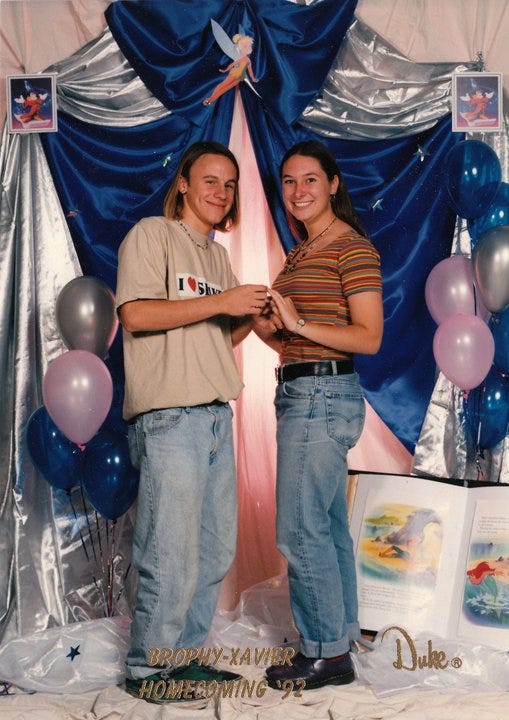

Where Lollapalooza launched its first tour in Phoenix, Arizona in July, the second, 30-city tour started at Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, California and would make one of its final stops in Phoenix in September. A lot had happened during that year. My friends and I were still in high school, but our hair was longer, we drank more beer, we’d grown confident in our coolness, and the alternative music culture that the first Lollapalooza helped build had taken over the world.

The 1991 tour was ahead of the curve. It was one of the few tickets that sold during what the media kept calling a “sluggish concert season.” It was also a test. “Music industry eyes were on the kick-off date,” wrote The Arizona Republic, “to see whether the blend of acts as diverse as rapper Ice-T and synthesizer dance band Nine Inch Nails could draw crowds in a concert season that has seen sluggish ticket sales nationwide for all but superstar acts.” It could. Some shows generated $1 million dollars. The second tour was slicker, better organized, and bigger.

In 1992, you no longer had to be cool to know about alternative music. You only had to be awake. Even if it wasn’t your thing, you couldn’t ignore it. Alternative music had arguably become the world’s biggest cultural commodity. By propelling bands like Nirvana and Soundgarden onto mainstream radio and MTV, Seattle music had spun the engines of global commerce and generated interest in similar, once-underground bands like Ministry, Lush, Pearl Jam, and the Jesus & Mary Chain—bands who were playing the second Lollapalooza. The tour packaged all the buzzy things up with a bow and sold it to you and 20,000 of your neighbors as counterculture. This was marketing magic at its finest: convincing us that, despite the crowds, this wasn’t mainstream! The mainstream media had a field day dissecting this emerging alternative music culture—marveling at music’s volume, gawking at the “weird” clothing, theorizing about the emotional place and generational wound that produced this—and consumers either ate it up or rolled their eyes. That was the climate of Lolla ’92.

“If the first year was an experiment, the next six were a victory lap,” wrote Spin. “As its popularity eclipsed its influence and the term ‘alternative rock’ lost its meaning, Lollapalooza became a summertime rite of passage for American teens rather than a platform for innovation.”

“What happened with Lollapalooza,” said Living Colour singer Vernon Reid, “and this is Perry Farrell’s genius, is it commodified ‘alternative,’ simultaneously carving out a new market and ending it.”

“In America, or any consumer-driven society,” said singer Henry Rollins, “anything that stands still long enough turns into a demographic and is marketed to. I can only speak for the first Lollapalooza, but I think it was very innocent. There’s no way the subsequent ones weren’t, in some way, calculated.”

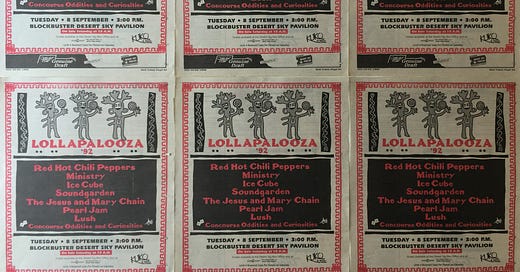

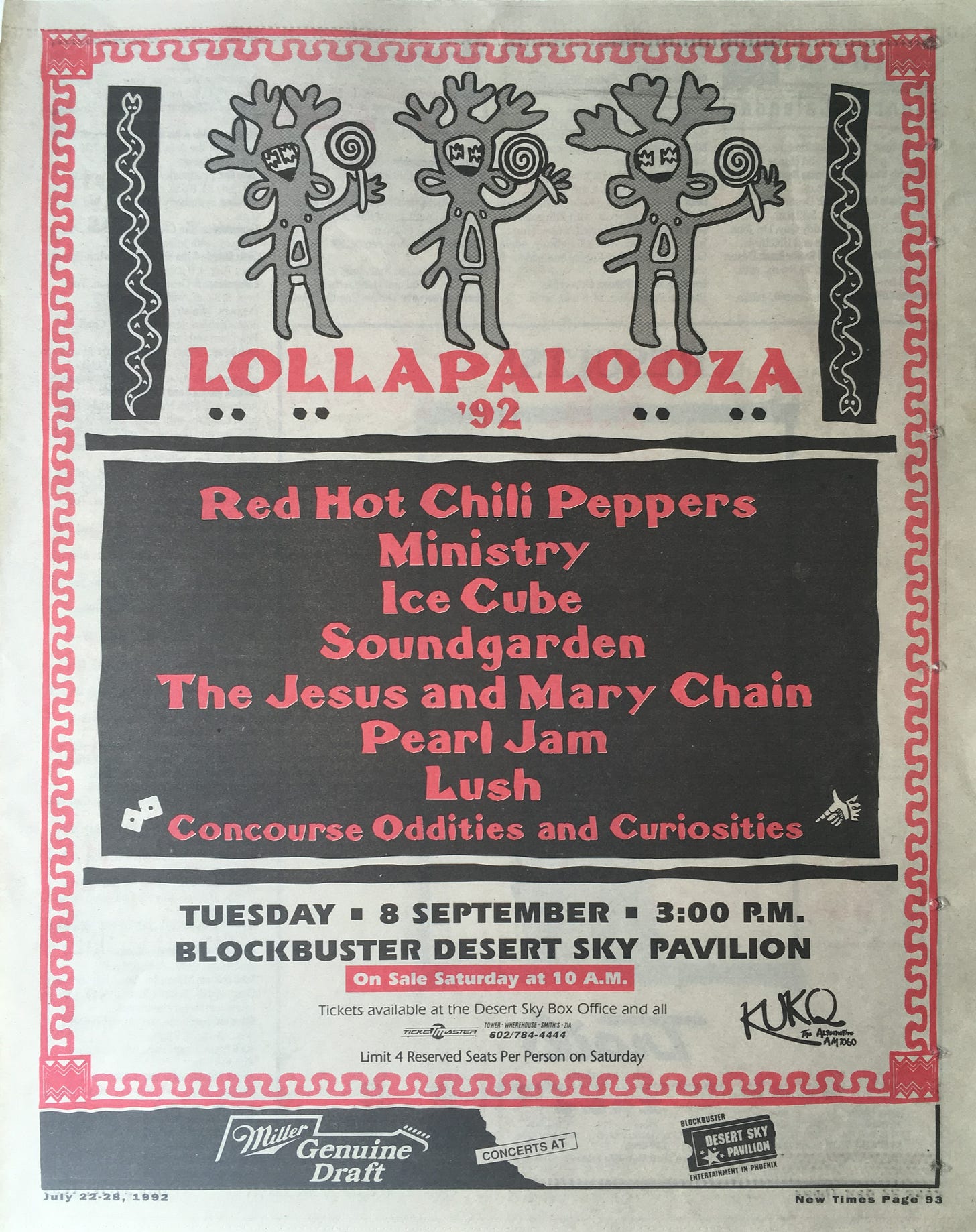

Set at Phoenix’s huge, impersonal outdoor Desert Sky Pavilion, the collective energy of this grand cultural moment was so invigorating that the bland location and scorching heat didn’t bother us. It turned our skin red. We sweated the entire nine hours, but it didn’t slow us down. The Chili Peppers and Ministry co-headlined. The Peppers’ album Blood Sugar Sex Magik had sold 2 million copies since we’d seen the band play the previous winter, and Ministry’s album Psalm 69: How to Succeed and How to Suck Eggs peaked, somehow, at No. 27 on the Billboard charts. “[N]ot bad for the rawest, angriest, most-intense rock band on the bill,” The Arizona Republic reported in their Lollapalooza guide. The middle of the bill included Soundgarden, The Jesus and Mary Chain, and Ice Cube—whose huge album The Predator wouldn’t even come out for six more months—and Pearl Jam. As popular as they were, Pearl Jam played the second slot, right after the underrated opener Lush, with their gorgeous, melodic pop. When the Lolla tour booked Pearl Jam, their debut album Ten hadn’t broken, but by the time the tour started in July, Ten had made Pearl Jam one of the most popular bands in the world. People were psyched to see this band they kept hearing so much about.

This second Lolla tour featured something new, a lively side-stage, where other bands played during the gaps between headliners. Bands included Perry’s new post-Jane’s band Porno for Pyros, the horrible Stone Temple Pilots, Chalk Circle, Shark Bait, the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow, Chris Cavacas, the keyboardist from Green on Red, a band I wouldn’t discover until a decade later (Cavacas was living in Tucson at the time), and an unlisted surprise performance by Temple Of The Dog for those of us lucky to catch it. That added up to nine hours of music.

As Megadeth said: Peace sells, but who’s buying? Lollapalooza proved that music sells, and kids were buying. And after last year’s test run, the second tour fixed the debut’s glitches. Desert Sky Pavilion had more shade than last year’s venue, Compton Terrace—meaning, it had shade at all. There was more food, more tents for activist groups, and more activities to entertain heatstroke’d kids between bands. “We’re proud of the fact that it’s closer to the Lollapalooza that we wanted to put on last year,” Lolla cofounder Marc Geiger told The Arizona Republic. “Last year, we accomplished 50% of what we wanted. This year, it’s closer to 80%. …Perry’s original idea was to have an entire day with a lot of music, art, media, and food.”

Now that Jane’s Addiction had disbanded, singer Perry Ferrell could focus on assembling a positively epic bill, and he decided to dial in his original vision for the festival and outdo himself. For this second year, MTV News, reported, Perry: “intended to be not just an annual celebration of music, but of youth culture too. He planned to have everything from ‘cyber-punk tents’ and Timothy Leary-sponsored computer raves aimed at, as he put it, ‘taking computers and making people high’ to debates between Democratic presidential hopefuls Bill Clinton and Jerry Brown. The idea was to make Lollapalooza ‘a coffeehouse for the youth to discuss what’s going on in their lifetimes,’ and while it may seem far-fetched today, back in the heady days of the early ’90s, all of this seemed not only possible, but downright imminent.”

“Cyber-punk” sounds so innocently dated. “Making people high” sounds like Perry.

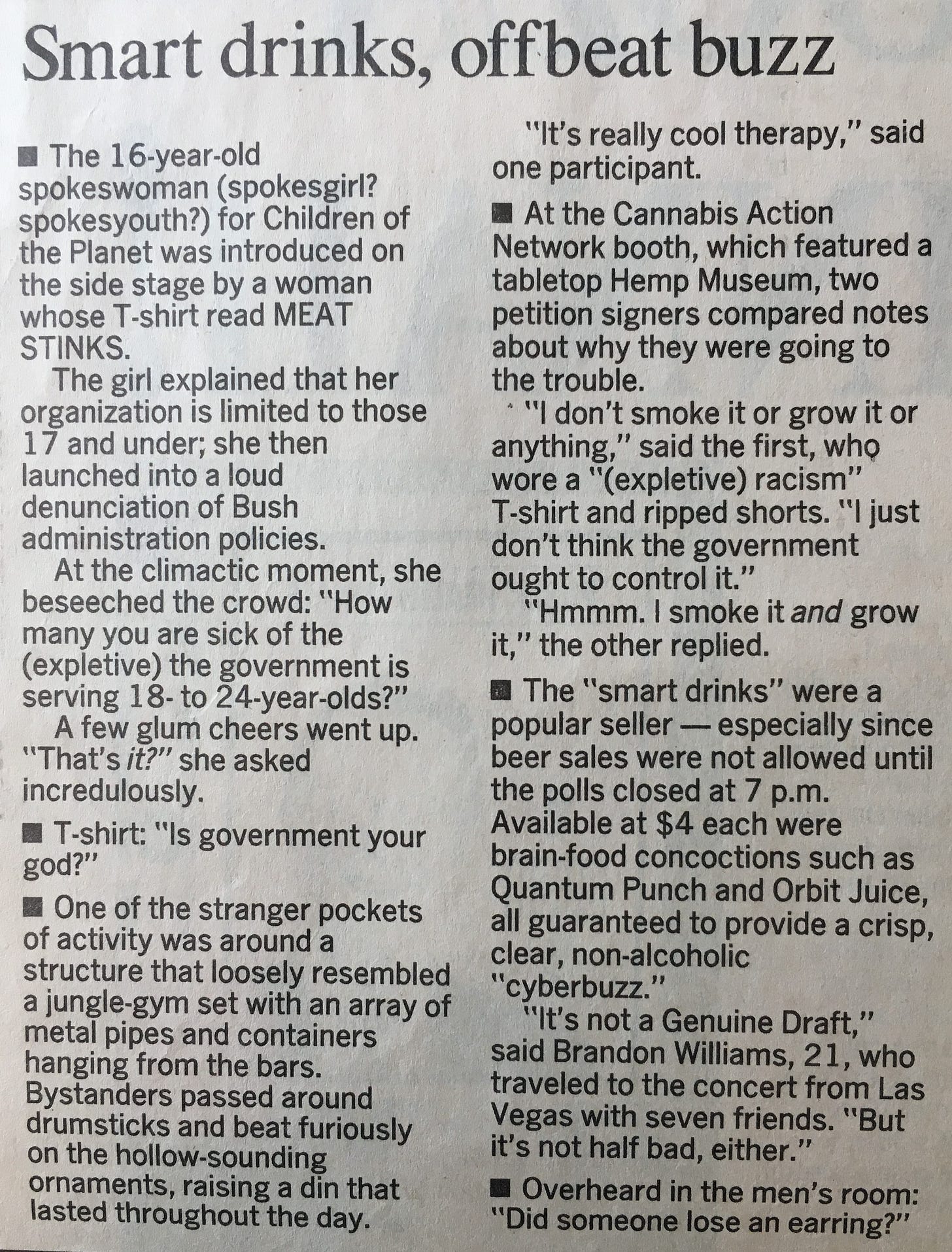

“Last year, a single tent and a number of concession stands represented all the non-musical aspects of the festival,” The Arizona Republic reported. Thanks to the involvement of mammoth rock promoter Bill Graham Presents, Lolla got a larger midway, which featured international food, a bookstore selling graphic novels, and tons of booths representing everyone from the Cannabis Action Network to Greenpeace, AIDS activists to People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Organizers went as far as creating the Lollapalooza Fund this year, which funded organizations that helped protect the rainforest, help the homeless, and fight AIDS. I don’t how much money the Fund provided those causes, but it sounded great on the surface.

“People are here for the music,” a 22-year-old Cannabis Action Network organizer told the paper, “but Lollapalooza is more than that. There is a new awareness out there that we’re tapping into.”

“Lollapalooza also consciously banned all corporations from participating through sponsorships, MTV broadcasts and radio syndicates shows,” New Route music magazine wrote in September 1991. “Hopefully Lollapalooza signals a turning point of the music industry’s excesses and greed. Making good music and treating the public with respect should be the agenda of the 1990s.” Change the greedy music industry? After a year of opportunity, it clearly did not. Instead, this tour made Perry and his fellow organizers RICH. And good for them. They’d never have day jobs again!

“We booked the Chili Peppers and worked our way backwards,” Geiger said. “We are as big as we want to be. We would never want to put this into venues that are not good for fearing music—like stadiums. But an amphitheater, an open field, is good.” It was also fucking hot.

The desert sun beat down on our sold-out crowd of 19,000 people like God was punishing us for our subcultural interests. This was the second largest crowd in the venue’s history. Only Billy Joel’s concert at Desert Sky’s opening night in November 1990 was bigger. The youth culture was out in force, and they had money to spend. Danny Zelisko, the Phoenix promoter who booked it at Desert Sky, said the secret to this tour’s success had been established already: “It’s basically a well-organized version of the parking lot at a Grateful Dead show.” The only Dead show my crew attended was actually here at Desert Sky, and we only came to buy drugs and experiences in the parking lot. We never went inside. My friend traded some hippie a gorgeous vintage Navajo squash blossom necklace for fake liquid mushrooms. That was an experience. At Lollapalooza, we arrived early so we wouldn’t miss a thing.

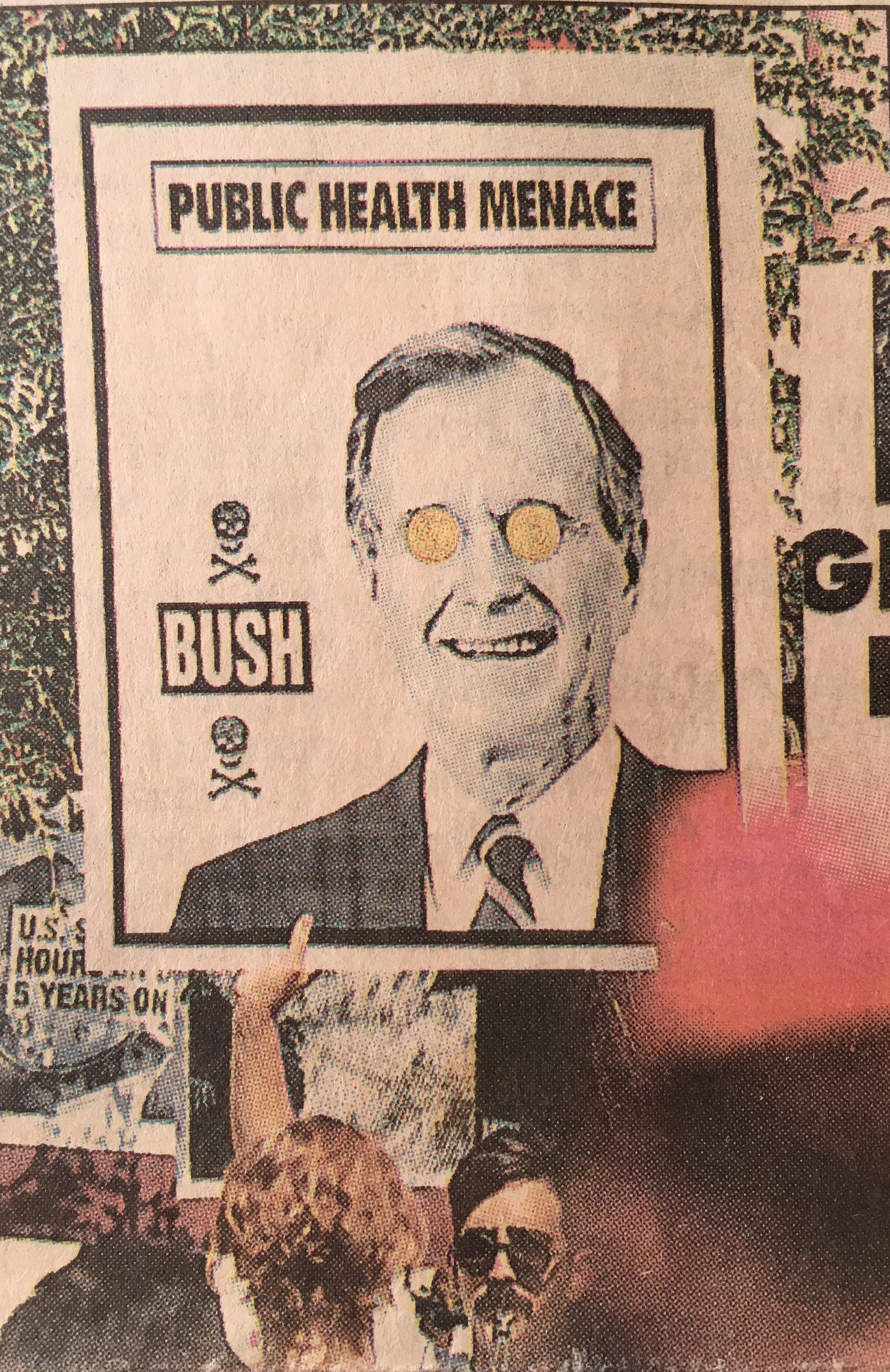

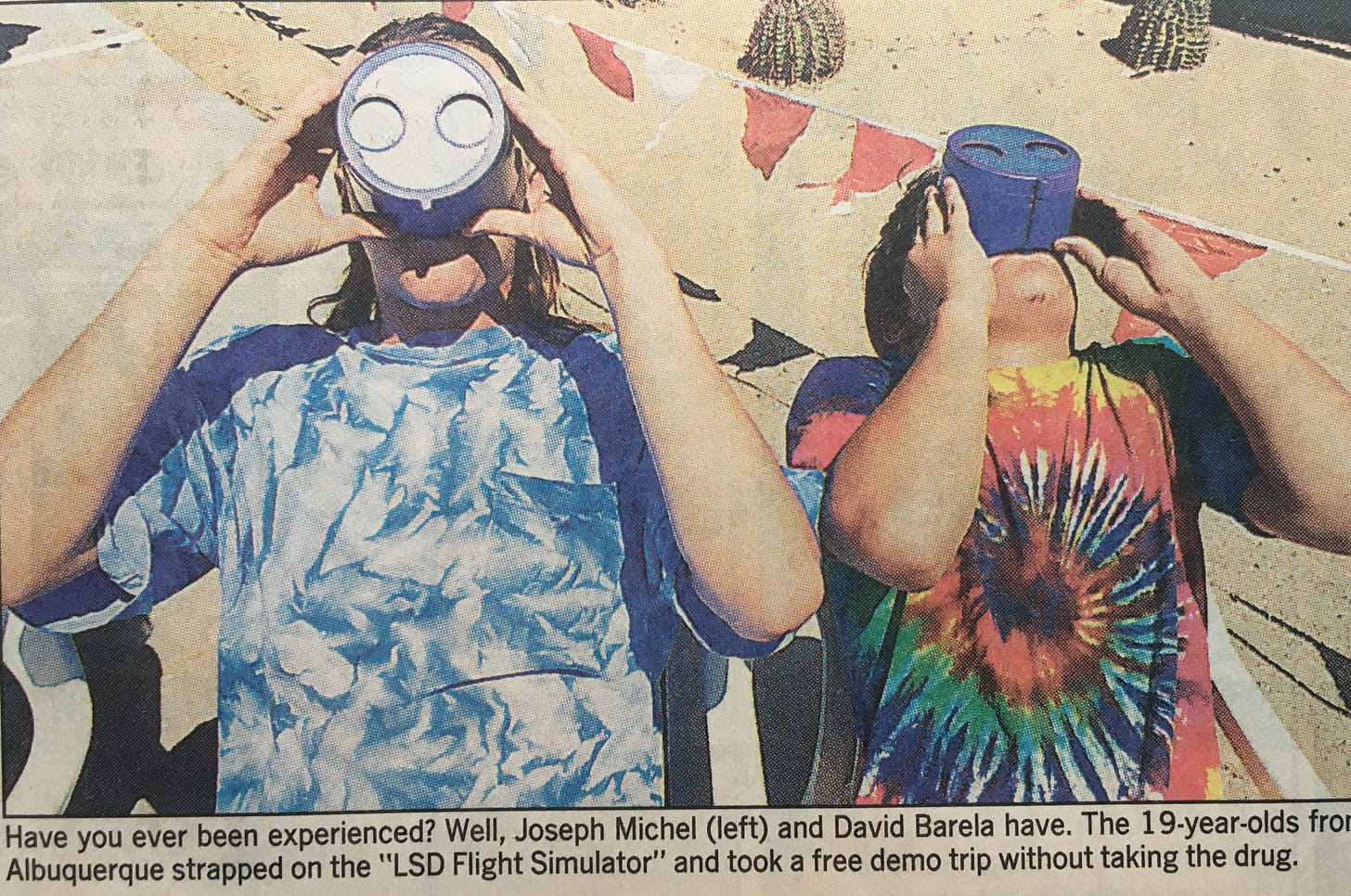

The parking lot opened at 10 for fans to line up. Doors opened at noon. Lush started the show around 1 p.m. You could bring in blankets and small plastic bottles of water, but no outside food, drinks, coolers, or lawn chairs. We stumbled around the sprawling property with the other sweat-soaked, empty handed teenagers. People stunk like hell. Everyone looked super ’90s: Shirtless dudes in their baggy shorts reaching over their kneecaps; women wearing flowing flower-pattern dresses and Doc Martins; blonde dreadlocks stinking of beeswax; beaded necklaces draped over sunburned clavicles, and more Doc Martins, always the Doc Martins. Some kids tied their long-sleeved flannels around their waists in the 100-degree heat! People wandered tent to tent. Some rode on a giant spinning gyroscope like at a fair. A dude had a prototype mask that simulated an LSD trip, which he called the “LSD Flight Simulator.” Kids lined up for that.

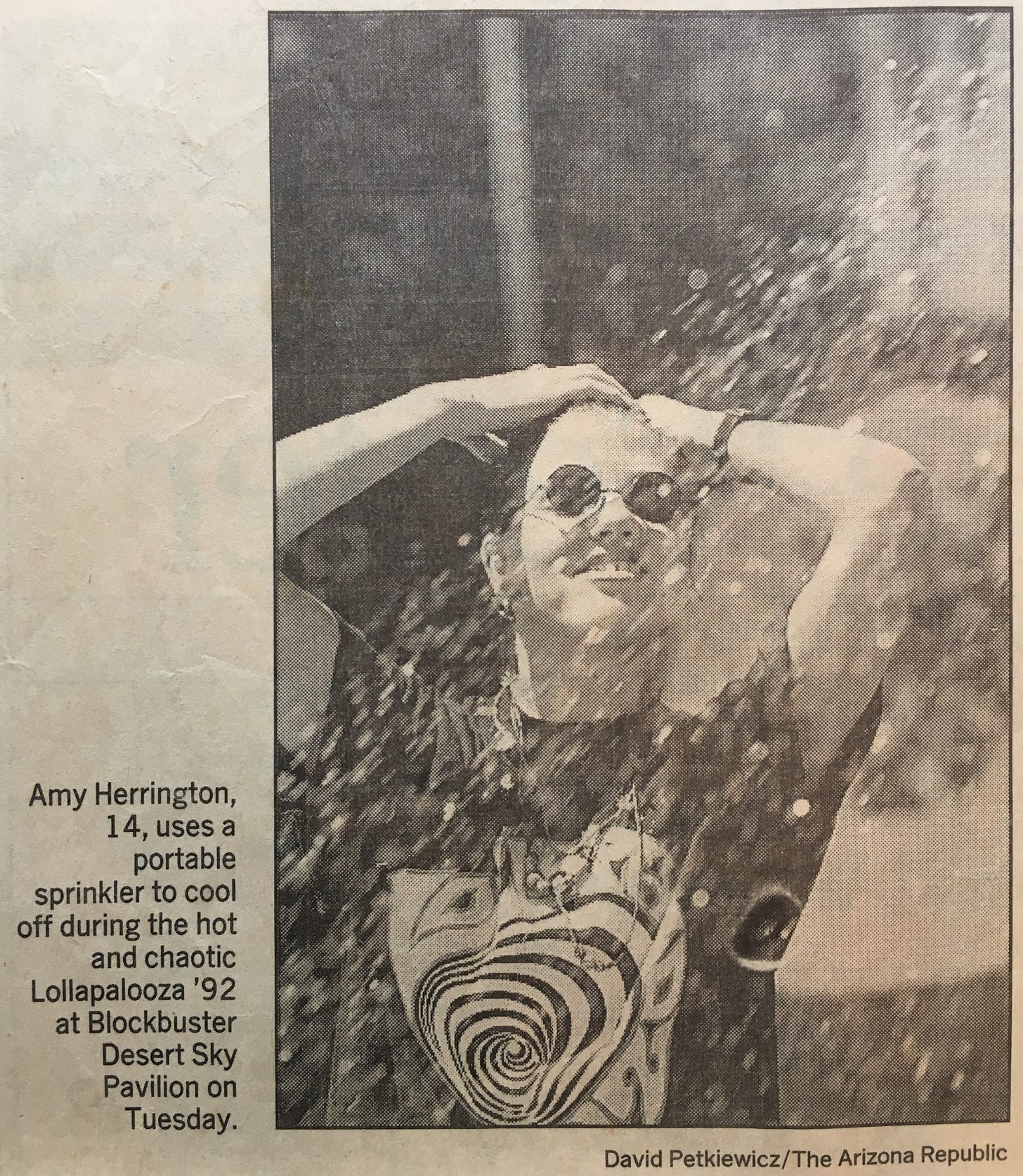

Life in the repackaged Dead show parking lot was all about drinking soda, eating overpriced food, and failing to find much shade. Between bands, we walked around, checking people out, soaking in what was clearly a scene. Temperatures stayed over 100 all day. People looked stoked. People looked trashed. Some had LSD eyes, others the worn faces of drunks about to pass out. According to The Arizona Republic, by 4 p.m., “paramedics had reported some 15 cases of heart exhaustion, including one 14-year-old girl who collapses while waiting in line, where thorough body searches were being conducted.”

I was sober. No matter how stoned and drunk I got on the weekends—which was a lot—I had a policy back then: stay sober at shows. I did this so I could fully embrace the experience and remember the details. I was a wild impulsive teen. Somehow I had the clarity to stick with this policy, and I still have so many show memories.

That said, I was tempted to try the Orbit Juice smart drink, which advertised a non-alcoholic “cyberbuzz.” I skipped it.

“Have you ever seen more earrings, tattoos, and dreadlocks in one place?” a 19-year-old Arizona State University commerce major told The Arizona Republic. She ditched “at least 40 classes” to attend this Tuesday show. She got in line in the parking lot to get in at 10 a.m.

People drove from as far away as Albuquerque and Las Vegas to attend. “It’s all here,” a 28-year-old San Diego ad agency executive said. “Music, people, freaks…what else could you ask for?”

Near a row of pay phones by one of the venue’s entrances, one Arizona Republic reporter overheard a guy from Berkeley, California saying, “Listen to me, man. This is a very definite vampire scene. They’re out here, man…”

The paper ran a lively sidebar of anecdotes and overheard conversations:

Alcohol didn’t go on sale until 7 p.m., so people had to come drunk or wait. Still, no one was arrested or seriously injured during the whole show. “It’s a mellow crowd,” one Phoenix police officer told The Arizona Republic. “We’ve been pleasantly surprised.” That was a sharp contrast to the huge Metallic and Guns N’ Roses show we went to the previous month at Phoenix International Raceway. “That concert drew 30,000,” the paper wrote, “spawned massive traffic delays, and resulted in the death of a 19-year-old man who drowned while trying to swim across a flooded Gila River near the concert site.” Jason, Chris, JR, and I went to that show to see Faith No More open. It was scorching. The heshers were mean in the pit, too, pushing us around during Faith No More—like we needed a reason to hate heshers anymore.

Lolla was the antithesis of that hesher show. This was our world, what Perry called the Alternative Nation, our kingdom of dyed blue hair and Docs, powered by music that swept heavy metal off commercial radio, as if retaliating for all the years we were subjected to trash like Poison.

Where last year we walked through a sparser crowd in a scorching spacious field, this year the crowd was packed shoulder-to-shoulder, and you could see the change: more people, more textbook alternative music outfits, and kids knew the lyrics. The Alternative Era was in full swing. It was clear how big this had become. Comparisons were drawn to London punk in 1977, to San Francisco in 1967, Athens, Georgia in the 1980s. But people were already pushing back against the idea of alternative music. Was it a real style? Was it a marketing gimmick people invented to sell and that the media had simply latched on? While covering it, mainstream media struggled to make sense of it. Journalists tried to define “alternative,” even as some admitted it couldn’t be defined.

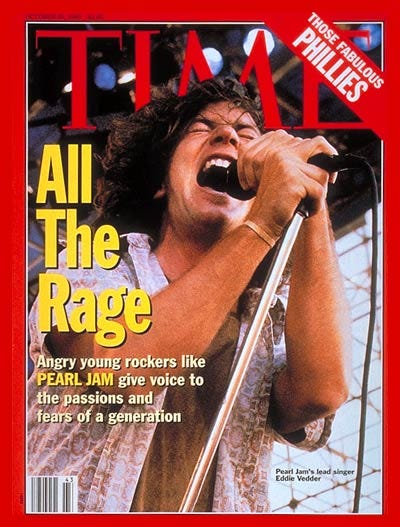

“Vedder is the product of the thriving world of alternative rock,” wrote Time in its October 25, 1993 cover story, “a musical genre that rejects the commercial values of mainstream pop. Alternative has no strict definition, but it has a feel. Its musicians reject show-biz glitz. They support progressive social causes. Many of them avoid dating groupies and models. Their music is usually guitar-driven, with experimental touches. While pop songs are often about love, alternative lyrics are usually about tougher feelings: despair, lust, confusion. Alternative rock is a reaction, especially among the twentysomething generation, to all the years of being subjected to Madonna’s changing hair color and MTV close-ups of George Michael’s butt.”

In 2021, I found this Time article in my box of music memorabilia in the basement. I’d clipped and saved it since 1993. This was my second time reading it. Now that I had done a lot of journalism myself, I could see the big journalistic fingerprints all over this story, the attempts to make sense of the new thing, to provide meaningful analysis, and in that could see the tendency to stitch elements together when there were only loose threads.

Time’s cover story was titled “All the Rage: Angry young rockers like Pearl Jam give voice to the passions and fears of a generation.” Rage wasn’t the music’s main ingredient. The article was really reaching for the universal story in the particulars, trying to make individuals like Vedder carry the weight of a generation. I wonder if my parents read that and feared for my friends and I. Rage was not my main experience of the music.

Time went on:

And therein lies the controversy: alternative music is currently one of the most potent forces in the mainstream, which has triggered an identity crisis and rancorous debate among musicians and fans. If these rockers are stars now, fans ask, haven’t they become everything we’re against? Nothing better symbolizes the struggle for this musical genre’s soul than the success of Pearl Jam, a band adored by followers but reviled by some fellow musicians as sellouts, poseurs or opportunists riding on the fame of their fellow Seattleites, Nirvana.

…In keeping with rock tradition, alternative is defiant. The twist is what it’s rebelling against. What angers today’s rockers and their fans is that life is so unjust, which they learned at a vulnerable age. Alternative rock is the sound of homes breaking. If you are in your teens or 20s, chances are your family has been through a divorce. Alternative music has become an emotional sound track (sic), speaking directly to unresolved issues of abandonment and unfairness. ‘I tried hard to have a father / But instead I had a dad,’ Nirvana’s Cobain sings on In Utero. One of Pearl Jam’s biggest hits, ‘Jeremy,’ is a song about a boy who kills himself in a classroom: ‘Daddy didn’t give attention / To the fact that Mommy didn’t care.’

I liked alternative music and I had a father. My parents weren’t divorced—although sometimes their fights sounded like they should be. I had other darkness in me, but Time didn’t capture what it was about my experience—vulnerability, disappointment, anger—that drew me to this music. It didn’t seem to be about something generational. It wasn’t about the culture. Like so much coverage of alternative music that the time, this article was trying to tie too many things together to make sense of things and tell a story. It’s meaning-making. It’s what humans do. Music doesn’t have to align with other quantifiable trends in the culture, like divorce rates or unemployment rates or George Bush’s presidency. Reading that “Alternative rock is a reaction,” I wondered: Is it really reacting to something at that moment in history? Couldn’t it just be the result of a particular set of peoples’ tastes in music at that time in their lives? The creative gestalt of a group of music-making friends? Maybe it’s not a genre or a feel, it’s just people with guitars making noise that appeases them. If we were going to react to anything with a generational movement, hopefully it would’ve been to something with more depth and social weight than pop stars like Madonna and George Michael on TV. What a load of crap that was.

Time was vaguely right about many alternative musicians’ value system, which rejects “show-biz glitz. They support progressive social causes. Many of them avoid dating groupies and models.” Many did. Not all. But the term “alternative” used to reference more than the music. Starting in the ’60s with garage bands and influential art bands like the Velvet Underground, underground bands were often underground because they rejected the trappings of mainstream stardom and conventional American life. That new sense of self—defining yourself in opposition to the mainstream—was initially a big part of what made early alternative bands “alternative” in the ’90s. It wasn’t about flannel, black nail polish, or dyed hair. It was about rejecting the life that was handed to you and creating your own. That is the definition of punk. It just had a different name in the early ’90s. It’s easier to sell something fresh and new. Media focused on clothes and a sense of generational pain. The clothes and music were different because the values were different, the approach was different, as all underground things are initially. Bands like Soundgarden and Mudhoney originally rejected convention, which often included materialism, sexism, racism, and rock star decadence, and they tried to find satisfaction and success differently than their rock predecessors. Pearl Jam is a great example.

When PJ drummer Dave Abbruzzese got to into the rock ‘n’ roll life as the band got famous, he started to clash with his bandmates. “Dave was a different egg for sure,” PJ bassist Jeff Ament told Spin. “There were a lot of things, personality wise, where I didn’t see eye to eye with him. He was more comfortable being a rock star than the rest of us. Partying, girls, cars. I don’t know if anyone was in the same space. Also, with Dave, musically, when you’d say, ‘I want this to sound more like the Buzzcocks,’ I don’t think he related to that at all. He was a technical guy, and we all played by feeling, or by seeing bands.” Enjoying the rock star trappings meant he no longer aligned with the band’s values or its public image, so they let him go.

So what to make of this term “alternative music”?

“It’s really a stupid word, actually,” Stone Temple Pilots’ singer Scott Weiland told Time. “It’s not underground anymore.”

Weiland would know. They never were.

Time quoted a great biting moment from Beavis and Butt-Head, where the two cartoon dumbasses watch Stone Temple Pilots’ “Plush” Video:

Beavis: “Is this Pearl Jam?”

Butt-Head: “This guy makes faces like Eddie Vedder.”

Beavis: “No way, Eddie Vedder makes faces like this guy.”

Butt-Head: “I heard these guys, like, came first and Pearl Jam ripped them off.”

Beavis: “No way, Pearl Jam came first.”

Butt-Head: “Well, they both suck.”

Beavis: “Hey Butt-Head, Pearl Jam doesn’t suck. They’re from Seattle.”

Butt-Head: “Oh yeah.”

In a 1993 interview, recording engineer and guitarist Steve Albini criticized Lollapalooza for marketing its music as alternative. “Lollapalooza is the worst example of corporate encroachment into what is supposed to be the underground,” he said. “It is just a large scale marketing of bands that pretend to be alternative but are in reality just another facet of the mass cultural exploitation scheme. I have no appreciation or affection for those bands and I have no interest in that whole circle. If Lollapalooza had Jesus Lizard and the Melvins and Fugazi and Slint then you could make a case that it was actually people on the vanguard of music. What it really is is the most popular bands on MTV that are not heavy metal.”

“Lollapalooza was a big alternative lie to begin with,” Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil told Rolling Stone. “They had a definite target demographic, and they hit that very well—white suburban people aged 18 to 24—which doesn’t seem very alternative to me. If you go to a Metallica or Guns n’ Roses show, you’ll see that the audience is actually more diverse socially and economically.” Thayil finds the perceived schism between metal and alternative “a ridiculous polarity. Look at the whole spectrum of music, and they are just a little bit apart. Look, we’re not talking about the difference between Moroccan music and hip-hop here.”

Thayil has always been one of the smartest, most measured voices in rock ‘n’ roll, with a mind that matches his guitar chops. It’s still easy to miss how much this music meant to us kids. Beneath the marketing, the listening experience was powerful, so the music was personal.

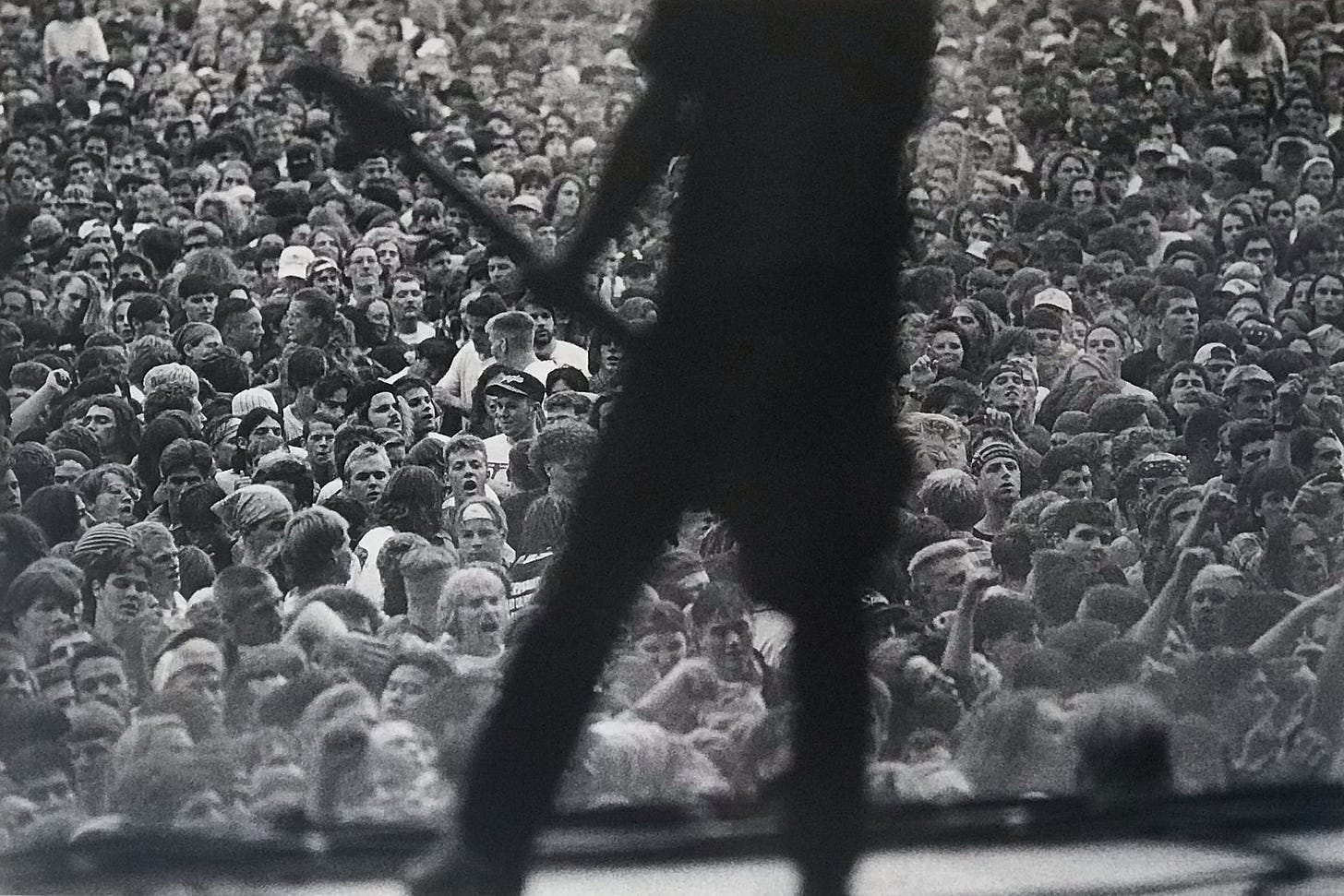

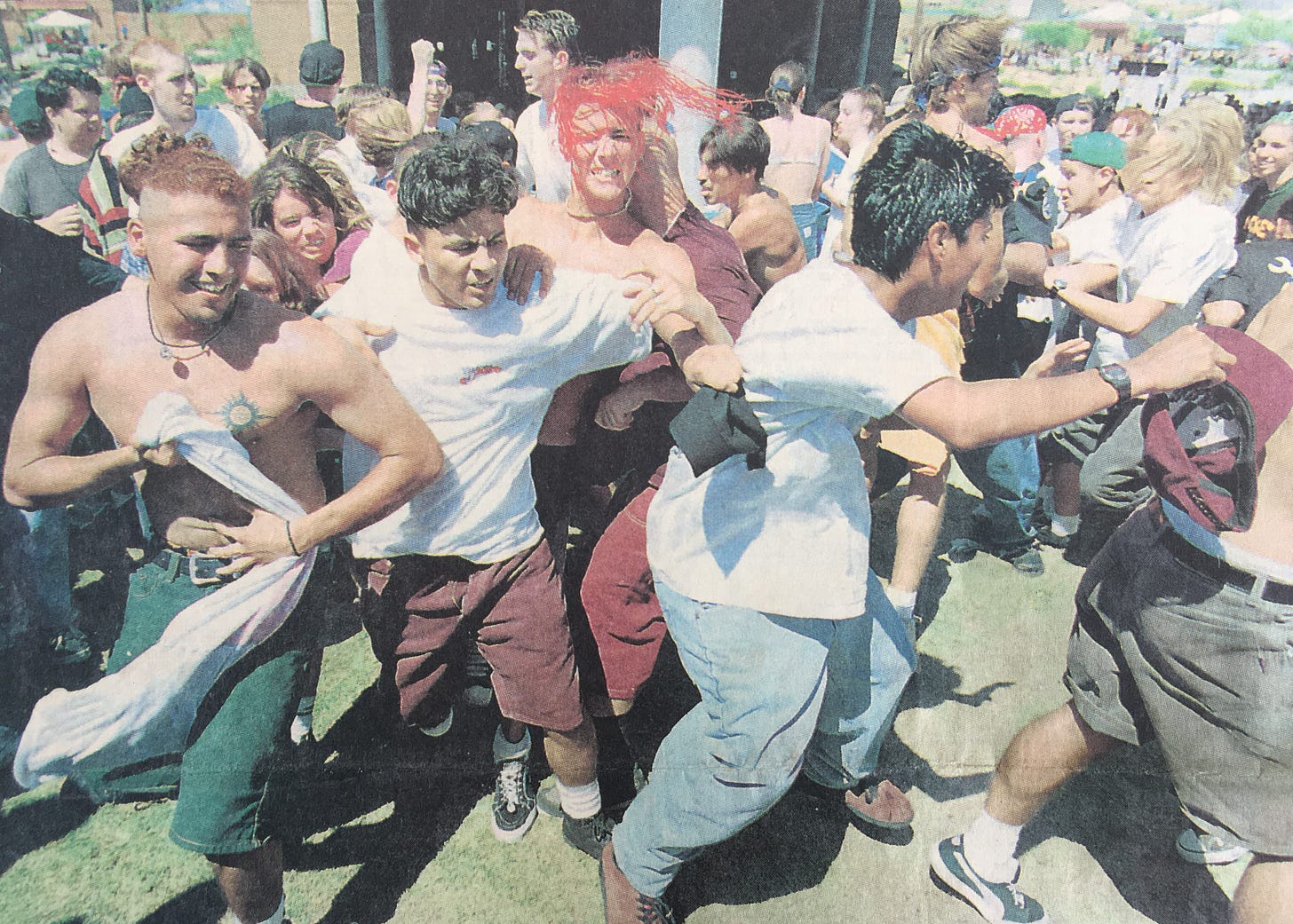

The kids in the crowd are easy to see as consumer demographics manipulated by marketing, but for some of us, this was the most exciting thing we’d ever experienced, not just the music but the crowds. Getting smashed is no fun. Being squeezed by the throngs till you can barely breath is terrifying, but being part of a surging unhinged crowd that big, being one of thousands of swaying, struggling, singing bodies pressed against a security barrier, all within feet of one of your rock ‘n’ roll idols? That’s electrifying. It’s cathartic. It’s primal. It’s like no other experience you can have. This is especially true for kids whose lives were quiet or mundane, defined by routine sports practice, Sunday mass, another plate of mac ‘n’ cheese.

It’s easy to lose sight of that from the stage. It’s easy to miss that when you’re just trading in ideas like Albini. Live music doesn’t exist in the realm of ideas any more than the listening experience does. It’s visceral. You feel it. That day, we felt a part of something huge. It was a cultural moment. It was special access. It was a collective experience. It was a teenage fantasy come true. Small club shows are almost always better than big shows, but when you looked around from your spot by the stage and saw a literal sea of humanity stretching infinitely around you, you felt how much bigger this was than your nightly homework, bigger than the sugary breakfast cereal in your bowl each morning, bigger than the stress of bullies harassing you for our acne or blue hair or torn black leggings at school. It was bigger than our average lives. Say what you want about the alternative music lie and Lollapalooza’s cunning marketing. As a kid, it was epic.

That’s why decades later, a Canadian photographer named Rick McGinnis remembered Lollapalooza’s crowd being more interesting to photograph than the bands. “The action in front of the stage looked brutal,” he said on his blog, but the kids “certainly seemed happy when I turned my camera on them, and I have dozens of frames of beaming, mugging faces picked out in the churning mass of bodies.”

It was the same in Phoenix.

Look at those faces. We were our wildest selves that day, too, and we were happy.

“It appealed to me and my friends because our generation is so dead to the world,” a young listener told Time. “There’s nothing waiting for us when we get out of school. …I don’t think all of these new fans know what they’re listening to. I hope it’s a short-term thing. I want my music back.”

That would never happen.

This music grew more mainstream every year, drawing in the jocks and meatheads we freaks defined ourselves in opposition to. Like every change in the culture, the alternative music thing got diluted, commodified, and tired as time went by. 1992, ’93, ’94, ’95—each subsequent Lollapalooza arrived in an environment where the alternative music it sold was less alternative, less subversive, more mainstream. Because really, if alternative music became popular mainstream music, then what was it alternative to?

Like every teenage phase, we grew up and moved on.

Defining “alternative music” was an important discussion. It still had no bearing on our experience of the show. When the bands came on, we were transfixed, because ultimately, only the music mattered.

When any band came on, the sea of people stilled, and those who were wandering around found a place to watch. Lush played and we waited for Pearl Jam. When they came on, the crowd erupted and eyes locked on the stage. The Seattle band had dressed for our desert summer, trading pants for shorts, but keeping their big ass boots. As always, Ament looked like he just finished a game of hoops. Their long hair must’ve been sweaty. I wouldn’t know. Mine never got as long as Veddar’s. Gossard had shaved his Love Bone hair off. It was a wise move for 100-degree weather. It was the look most of us would take soon, too, shaving off the long hair we’d meticulously grown in high school.

The band launched into their set with a cover of the Dead Boys’ “Sonic Reducer.” The place went nuts. We stood in back in general admission, under the punishing sun, and the mosh pits formed at different points throughout the crowd. We watched the band but also watched the people in front of the stage, who were having the most fun. Watching bands from Desert Sky’s general admission sucked. The huge grassy area was in full exposed sun and separated from the stage by the covered, shaded rows of reserve seats. To see the band, you stared at their distant figures, or you watched them on the Jumbotron screen thing. We hadn’t come to watch bands on a screen. We decided we’d be missing out if we stayed back there. So a few of us leapt the fence and cut through the crowd in the reserved section, squeezing past sweaty body after sweaty body, pressing against shirtless dudes with stringer wet hair, until we arrived right up front where we watched as the teeming mosh pits swirled around us. On paper, Lollapalooza would seem too big to feel intimate, but once we got up by the stage, the band had enough energy to make up for the scale. This was our third Pearl Jam show in less than a year. We’d just seem them headline a small outdoor venue four months earlier, and they were as energetic as the first time.

After the first song ended, Vedder hyped the crowd. “I don’t know about you,” he said, “but I’ve been really looking forward to this. Oh that’s right, you can’t be drinkin’ till 7 o’clock. I forgot. Well I hope you voted instead.” Then they tore into “Even Flow.”

We weren’t the only ones to sneak up front. Fans knocked over the low fence that security had erected around the general admission area, and they knocked over the steel barricades to flood the reserved front rows. Kids pressed against my back, pressing my ribs against the security barrier in front of the stage. But Vedder was right there in front of me once again, singing and flinging his hair from his face, while guitarist Stone Gossard danced and shimmied his feet in his weird way as he played. This was the incredible view we’d missed at our first Pearl Jam show in December 1991.

The band jumped up and down constantly. Their drummer was a badass up close. Bassist Jeff Ament launched himself so high off the drum riser you couldn’t believe his ankles didn’t snap when he landed. He was an athlete. His old singer Andrew Wood once described him as a jock, but even while leaping, you could hear what a good bassist he was. During the song “Porch,” he leapt off the riser but seemed unsatisfied with his landing. So he ran back and launched off it again, flying like Michael Jordan slam-dunking a ball, except while playing bass. The band clearly still enjoyed themselves. Vedder courted the fans, talking to us and slapping outstretched hands. I unsuccessfully searched for ways to get past security so I could lift myself up on stage and dive off. I couldn’t. Instead, I sang. I raised my silly fist, and I spent my time jumping up and down as the sweaty backs of other kids spun in the circular mosh pit.

In the four months that had passed since our last Pearl Jam show, the band had changed little, but their audience had changed a lot. They had officially become popular. “After a slow and steady build,” Rolling Stone wrote, ”Ten finally reached the upper echelons of the Billboard 200 in August 1992, nearly a full year after its release.” Ten would probably have reached close to the Billboard No. 1 spot if Billy Ray Cyrus’ Some Gave All hadn’t kept it out of there. The mullet-head’s debut spent 17 straight weeks at No. 1 during the spring, summer, and fall of 1992. Despite its interference, Ten landed the No. 2 spot during August, September, and October, which meant they peaked commercially during these Lollapalooza shows. By October 1993, over 90 weeks since its release, Ten had sold 6 million copies and remained on the Billboard Top 30 album chart.

All around us, people knew the words. They sang along. They copied the crowd surfing they’d seen on the videos. Jocks were into it now, too. Instead of being outside of underground circles and making fun of us freaks, they had those haircuts of people growing their hair long—the sort of preliminary cut, too short to put in a ponytail, but long enough they could barely tuck it behind their ears. Fuck them, we thought. They don’t have a clue. Strangers’ soda and alcohol sweat soaked our clothes so the effluence of strangers mixed together in a single toxic sludge, leaving a rank salty residue on our skin. My blonde hair quickly turned stringy and crusted with sweat. People were nuts for this band. This intensity would come to define their fanbase for the next three decades.

One measure of alternative music’s popularity at this pivotal moment can be measured in the faces of fans in the crowd. Twenty-four years later, I found footage of the whole show on YoutTube.

This show proved unique in the annals or Pearl Jam history. Lollapalooza co-founder Ted Gardner hired a bohemian named Flano as the tour’s official massage therapist. Flano brought a portable VHS camcorder with him. Although he wasn’t Pearl Jam’s official masseuse, he later said, “I just happened to get close with Dave Abbruzzese as he and most of the drummers, Chad and Bill R., would have me work on them before their set.” Like us, Pearl Jam’s energy impressed him, so he took advantage of his high level of access and shot bits of shows at different locations. For some reason, he shot Pearl Jam’s entire set at our show, right from the stage, and a bunch of Ministry’s set at night. As he told a crew member backstage during Ministry’s Phoenix set: “This is Flano in Flano homecam, and I will be showing this to my children.” While he stalked the stage beside Ministry’s guitarist and behind Ministry’s drummer that night, my friends and I were somewhere out there in the darkness, jamming to Ministry while kids lit bonfires in the audience nearby. At Irvine Meadows, Flano talks to two shirtless dudes wearing loud pants and leather boots. They aggressively yell the names of bands they’re excited to see and ask how he got his camera in. “I’m with the production,” Flano says. “And I’m making a documentary. ON YOU!” One yells, “You’ll be on MTV.” Flano says, “No no, bad word. Sorry guys. Wrong answer.” And he leaves. After the tour, from inside some kind of tropical beach hut, Flano turned the camera on himself and told viewers: “I just want to say, I really had a good time with all of you. So. So, hey. I hope your backs are feeling well. I hope someday you can visit Thailand.” And to Pearl Jam specifically, he said: “I’m really wishing the new album that you guys are going to cut in March to just kick ass.”

He edited his epic footage down to two, four-hour VHS tapes and gave copies to each band and the crew members. Thankfully, intrepid fans have sourced first-generation copies of Flano’s tapes and posted them, even combining the video with high quality digital audio. I don’t know much more about Flano than what he and fans have said on YouTube and fan sites, but there’s no greater gift than letting you re-watch a concert that’s been stuck in your brain for decades. He didn’t capture the bonfires people set in the crowd during Ministry’s show—which people talked about those for years—but Flano did film Flea play Black Sabbath’s song “Supernaut” with them. The following year, Flea and Ministry’s singer Al Jorgensen played in the short-lived super-group P that ended up performing at the Viper Room while Phoenix overdosed on a speedball outside.

Watching the footage in 2021—seeing it for the first time since I lived it—I can see the frenzy from the outside, as I would had I been the parents of us kids, or a reporter covering the event. Look at us. It was Beatlemania all over again.

As Vedder sang “Black,” kids in the crowd sang back “Sheets of empty canvas / Untouched sheets of clay.”

Versus:

Thank god for Flano.

As the images passed before my eyes and sparked ancient memories, I thought I saw myself on screen. I leaned forward and hit pause. There, on the top left corner at the 10:07 mark, Vedder leans at the foot of the stage and sings “Why go home?” and in front of him, a dude with a striped shirt and long blonde hair flashes in the crowd. So I craned my neck and leaned close to study face, played the brief segment over and over to see if it was me. Was it me? It wasn’t me. But was it? I studied the kid’s features—the shape of his nose, the way his hair draped as he leaned forward—studying him against Vedder’s silhouette as if I wanted proof that my youth wasn’t wasted like The Who sang, that I was there, man, at the big cultural happening.

It isn’t me. White dudes with blonde hair and striped shirts were a dime-a-dozen in 1992. My hair wasn’t that long that year anyway. It was on its way. It would never reach Vedder level. I didn’t have the follicles for it, so when my split ends got too bad and my future baldness became undeniable during college, I gave up trying and cut it in 1994. But in 1992, I wanted nothing more than to have long flowing locks like my friends and Mudhoney and Chris Cornell did. (And that all these middle aged rock ‘n’ rollers like Dave Grohl and J Mascis still have in 2021 thanks to good genetics. Damn, they’re lucky. I got shafted in the follicle department. Thanks, Grandpa Shapiro! Okay, sorry. Moving through my bald guy rage.)

Anyway, at that point in the show, my friends and I could’ve been anywhere in that crowd full of people wearing Cheshire cat hats and knee-length shorts so long you could trip over them. Anyone of those blurry pixelated faces could be mine.

And boom: As I watched the footage for the first time and crazily zeroed in on my doppelganger, someone bought two of the vintage Mr. Bungle flyers I was selling on eBay for $60. Wow, I thought, the ’90s lives!

I returned to the footage.

One Arizona Republic reporter heard Pearl Jam’s performance as “a strong, well-received set” and called “Lollapalooza a winnah!” The paper’s pop music reporter, Salvatore Caputo, heard hype. “Pearl Jam’s Vedder acted like an egotistical jerk,” Caputo wrote, before complaining about their decision to cover The Who’s “Baba O’Riley (Teenage Wasteland).” Caputo’s headline called Lollapalooza “a snooza.” “I’ve seen rock’s future and…it is boredom,” he wrote. For him, the show’s only excitement “came from watching my back to keep overeager fans from trampling me.” Oh, no! Everywhere Caputo went, he only found rude, aggressive fans, disorganization, and disappointment. He’d covered the first Lollapalooza. Somehow he didn’t experience this as an equally exciting version. About us fans who cut through the reserved section to reach the stage, he said, “If I had paid extra for reserved seats, I would be extremely angry about the way folks helped themselves to better seats than they paid for.” (Note: We didn’t sit.) “Somebody tell these bands that urge fans to violate the security arrangements that they’re putting their own fans in jeopardy and that they’re costing their own fans money. …If they want everyone up front, they should throw a free show and not hire security.” Welcome to a rock show, man. Security’s handling of fans in the crowd didn’t, as Caputo wanted, “make the situation any safer for the people who wanted to stay at their seats and enjoy the show.” If sitting in a chair during live music is your idea of enjoying the show, then don’t go to a loud, all-day rock show. Go to the beach or a mall food court. Even if he could sit quietly in his reserve seat, he wouldn’t have enjoyed it. He disliked nearly every band in the 9-hour show. Lush’s vocals were indecipherable to him, and the guitarist spent too much time sitting. (Caputo’s rating of Lush: C minus) The Jesus and Mary Chain, a so-called “noise-band,” “wasn’t loud enough or hard enough to move the crowd much.” (His rating: C) Ice Cube “emphasized dance energy over messages, despite all his brooding, angry lyrics.” (Huh?) Soundgarden tried and failed to “move the crowd” as much as Pearl Jam. (B minus.) “Ministry’s pseudo-tribal ritual was so calculatedly dumb and cynical,” he wrote, “like a noisy version of Gilligan’s Island—that I had to laugh.” And the headlining Red Hot Chili Peppers were “way overrated” to him, which is true. He said the band’s original songs pale in comparison to their Hendrix and Stevie Wonder convers. Finally something we agree on. (His rating: C plus) It seems he mistook being a columnist for being a grump; yet somehow he worked as the Republic’s pop music reporter from 1989 to 1997, by which time he must’ve looked so out of step.

Whatever. Flano’s footage shows how wrong Caputo was about Vedder’s arrogance.

After Pearl Jam’s set, we walked back to our friends in general admission. Waiting on the grass for Soundgarden to play, we heard people talking about how Vedder was strolling around in the audience. The nearby kids I asked didn’t know anything more about it than that—“Gossip,” they said with a shrug. “But cool.” So we went out walking, looking to see what other bands were strolling around. On the side stage we watched the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow pierce and poke their bodies, and we were like whatever, and after sunset, after hearing more gossip about it happening, we managed to catch Vedder and Chris Cornell playing Temple of the Dog songs in what proved to be one of that side-project’s few public performances. They just did it in Phoenix for some reason, and rarely did it again. Maybe the vibe was right. Maybe they knew the tour was ending soon. And again, someone filmed it. What a coupe for our teenage crew!

Grunge ruled this Lollapalooza.

The Jesus and Mary Chain shared the bill with all those loud, testosterone-driven, guitar bands. As singer Jim Reid told Option magazine in September 1992, “The idea behind the whole tour is to get people to listen to different kinds of music. But there’s just too much of one kind this year. And it’s not really just the music. There’s too much of this macho attitude out there, too much of a chest-beating kind of thing. Even with Ice Cube on the program, the audience is mostly male and certainly 99% white.”

“To be honest with you,” his brother William Reid said, “the whole thing has been much, much too hard. I’d like for there to have been a softer approach.” This from the guys who loved to talk shit and self-aggrandize, and who’d infamously started a riot at their North London Poly show in 1985. They’d changed. That’s a good thing. The Grunge era was anything but soft. In my youth, I needed music to help build up my hard shell and squelch my interior, but brilliant, sensitive songwriters like Cornell wouldn’t let me, because they played both hard and soft. He was one of the most gifted songwriters of his and any era, and partly because he had such emotional range.

Ministry mastermind Al Jourgenson liked the tour. “The only thing I said about Lollapalooza the whole time, is it was a tour I really wish I could hate, and I didn’t,” Al told MTV. “I wound up really liking it. I made some friendships on that tour that will last forever. …I really had a good time. Everyone was, like, really good. I met a lot of really nice people on this tour.”

Chicago Reader writer Bill Wyman hated the ’92 tour. Only Ministry was a “pretty good group” to him. The Jesus and Mary Chain were influential but passé, and the rest, he said in his article “Lollapaloser,” had “an ephemeral air about them.” Of course, he was wrong. Ice Cube enjoys a lucrative acting career, Pearl Jam is huge, and the Chili Peppers still release new music, no matter how bad it is. Wyman found the show too long. He didn’t like the non-musical program either. “The festival did offer its diversions,” he said, “but they weren’t enough: everywhere you went there were hordes of people, crowding around flower boxes, standing in lines for bathrooms, food, or drink, aimlessly pushing this way and that.” 30,000 people attended his Chicago show. That was nearly 30,000 too many.

My friends and I loved our show. We left the second Lollapalooza on a high. Unlike subsequent tours, the show was perfect, one of the best days of my life at one of the best shows of my life, and I’ve seen hundreds.

When the tour ended, the alternative era marched on, along with our teenage lives. Soon adolescence would end, and we’d graduate high school and go our own ways: into the navy, into college, the Pacific Northwest, drug addiction, marriage, parenting, before we’d reunite. For now, we kept listening to hip-hip, Soundgarden, and loud rock ‘n’ roll.

In 1993, Lollapalooza returned to Phoenix’s Compton Terrace, the venue where it started in 1991. The lineup included the most awesomely ’90s set: Alice in Chains, Arrested Development, Fishbone, Dinosaur Jr, Rage Against the Machine, Babes in Toyland, Tool, Primus, Front 242, and it featured Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore playing the second slot on the second stage, solo, in the middle of the day. The temperature reached 105.

“A mother with a baby nearly 3 months old tries to comfort the broiling child,” pop critic Salvatore Caputo and his Arizona Republic crew reported. “A girl wearing a T-shirt with a picture of Earth and the slogan ‘Love your mother,’ finished the bottle of natural spring water with a satisfied gasp, dropped the plastic bottle on the ground and moved on.”

18,000 people attended. Organizers had learned from their previous mistakes by offering fans relief from the heat. “Frying fans lined up to douse themselves under one of 10 shower heads—the wait in the sun was up to an hour. But said one dripping woman in a sizzling black Lollapalooza T-shirt, ‘It’s better than real rain.’”

Caputo still enjoyed taking jabs at attendees’ appearances. “As the odes to non-conformity blare,” he wrote, “it’s fun to note just how few people are wearing anything but black boots on their feet.” A substitute teacher named Ken, wearing a backwards ball cap and a Red Hot Chili Peppers shirt, told one reporter that he was going hard at this show because he’d missed last year. “I’m ready for the mosh pit to crank up,” he said, “cuz I’m ready to kick some heads.”

The ’93 tour was old enough to get described as an institution. The music it sold was still labeled alternative. By 1994, Caputo’s coverage asked “Is Lollapalooza getting old?” Me: No. The ’94 tour was stacked with killer bands like L7, Tribe Called Quest, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, George Clinton & the P-Funk Allstars, Beastie Boys, The Breeders, Shonen Knife, The Pharcyde, Stereolab, and it had The Smashing Pumpkins headline. It was old as in mature but the music was more popular than ever. “Security could not contain the crush of people who jumped the fence and the seats,” The Arizona Republic reported. “Rows of folding chairs set up in the orchestra pit immediately went down. Spectators at the front of the stage passed the seats over their heads. They looked like metal and plastic caterpillars as security men pulled the seats out of harm’s way. The crowd moshed furiously.” It was 1992 all over again. But the idea of alternative music had definitely lost currency, because it had become too mainstream to convivence anyone it was alternative to anything. “Mainstream Alternative,” was the title of Caputo’s article. “Lollapalooza blends idealism with commercialism in an embrace so tight,” he wrote, “it’s hard to discern that they are opposing forces.” Caputo was right about that.

Alternative music peaked around 1995 and ’96, and as it took a long slide down the toilet, the next new thing emerged: ska-punk, then the swing revival, then—thank god—alt-country.

People say Lollapalooza turned for the worst by ’95. Critics felt Lollapalooza had become too big, too much a carnival that made the music the side-show, and that it had drawn too much of the music industry bullshit and corporate sponsorship that it had initially prohibited. It embodied the tightrope that ’90s musicians had to walk: making a living without letting outside corporate interests take over—“selling out” people called in the ’90s. More about that later.

In 1995, Jonathan L, the KUKQ program director who organized the station’s popular annual music festivals, Q-Fest, told the Phoenix New Times:

“Lollapalooza was a great idea when it began,” KUKQ’s director says. “I don’t think it's that great anymore.” Not with soaring ticket prices. Not with an atmosphere that Jonathan describes as an industry feeding frenzy. Not at a festival where “all these record companies fight over who’s gonna have who on the bill.”

Once promoters start throwing in tattoo booths, body-piercing demonstrations and virtual-reality playgrounds, he says, the musicians become almost an inconvenient afterthought.

“I love tattoos,” Jonathan says, “but why have a tattoo booth while the music’s going on?”

So KUKQ Fest will have no tattooing. Instead, it will have free cigars for the first 50 people through the door; leather-clad women parading about with body jewelry; and a boxing ring stocked with hairy-backed brutes (a.k.a. bona fide pro/am boxers) taking shots at one another throughout this “nice night of aggression.”

Jonathan suggests his gimmicks are less offensive than Lollapalooza’s because they reinforce his event’s aggro-rock theme, which might be described as a Vegas fight night, postapocalypse. “People aren’t going [to Lollapalooza] for the music anymore,” he says. “They’re going for the event.”

In 1995, Jane’s Addiction bassist Eric Avery nailed it: “Alternative music has become the same thing as pop music. It was popular music. And then the word just became pop and now pop means something else. It’s no longer the original meaning of the term, and the same thing is true for alternative music. …alternative music, by definition, can’t be what you hear on the radio all the time. Because then, that’s not an alternative.” He knows. His band ushered in that era.

By 1996, alternative was dead.

“We started in ’91,” Marc Geiger told Spin, “and by ’96 underground music was over. Third Eye Blind was a cool band. Matchbox Twenty was the fucking next Radiohead.”

Perry sold his stakes and pulled out.

Rolling Stone: “With Farrell out of the picture, the festival’s most public face is Geiger, a former booking agent who must field endless questions about how long Lollapalooza can sustain its five-year run of solid profitability and whether it can retain its credibility at a time when the term ‘alternative rock’ seems to have lost all meaning. ‘It has been an uncomfortable couple of years for us,’ Geiger admits. ‘We think the majority of what’s called alternative music is such shit. Listen to any major-city radio station in this country—you’ll hear the same 10 to 12 bands. We don’t want to turn into a radio-station festival.’”

Rolling Stone talked with Perry about whether he or Lollapalooza hung around for too long:

“I did that to a point,” says the man whose gold credit card is embossed with the words ‘Perry Farrell/Lollapalooza.’ “There were a couple of years that I didn’t care. I probably should have given up before, but I had pride invested. It’s not 100% a bad thing giving the kids a chance to see these kinds of bands every year. But I mean, Metallica, who am I kidding? I thought, enough—at least I listened to the other bands. Maybe I don’t belong here. I didn’t feel my dreams and aspirations could be played out here.” ...“It’s not anger,” says Farrell of his current feelings toward Lollapalooza. “I just see where there’s progress to be made. I’m impatient, bored—that’s the extent of it. I’d work with Lollapalooza tomorrow. Let’s get away from the teamster venues, get away from the concrete and out to nature, get a contact high. You know, I hear Metallica’s got a haircut—so God bless ’em.”

In 1997, Lollapalooza went on a hiatus. It reemerged in 2003, but they canceled the 2004 due to low ticket sales. Touring was part of what originally set Lollapalooza apart from other music festivals. Perry and his crew reformulated the festival by grounding it and booked it as a stationary two-day festival in Chicago’s Grant Park in the summer of 2005. That worked. People came. People loved it. Now it happens there every summer, though it would never be what it once was. It didn’t have to be. Like music itself, it changed, and modern attendees have a different relationship with it. To people today, it’s a fun weekend festival, not a ’90s throwback. And frankly, it’s enjoyed a longer life than many of the bands that helped make it a cultural institution. Somehow Perry is still alive, too, still making music. Al from Ministry is alive, too, and sober. And Lollapalooza continues to make people happy. That’s a great legacy. It doesn’t hurt that people made good money, too.

As Perry sang in “Mountain Song:”

You better cash in!

Cash in now, honey

Cash in now

Cash in now, baby, yeah

Cash in now, honey

Cash in, Miss Smith

Cash in now, baby!

Oh-oh-oh, Oh-oh!