Mr. Bungle

Breathing Through a Tiny Straw

“Often I feel that the public that took to this [debut] album had pre-existing mental problems that the wide distribution of the CD only exacerbated. So when I hear about how this music affected these youngsters, it really just makes me sad.” ─Mr. Bungle guitarist Trey Spruance

For a brief time during their 1992 tour, Mr. Bungle played one of rock ‘n roll’s weirdest cover songs.

The drummer starts with a simple marching beat, rolling his sticks atop the snare and hitting the floor tom every second measure, back and forth with no musical accompaniment. Boom, clack, boom—beat builds tension. It also puts you in a trance. Then singer Mike Patton destroys the calm when he starts snarling lyrics.

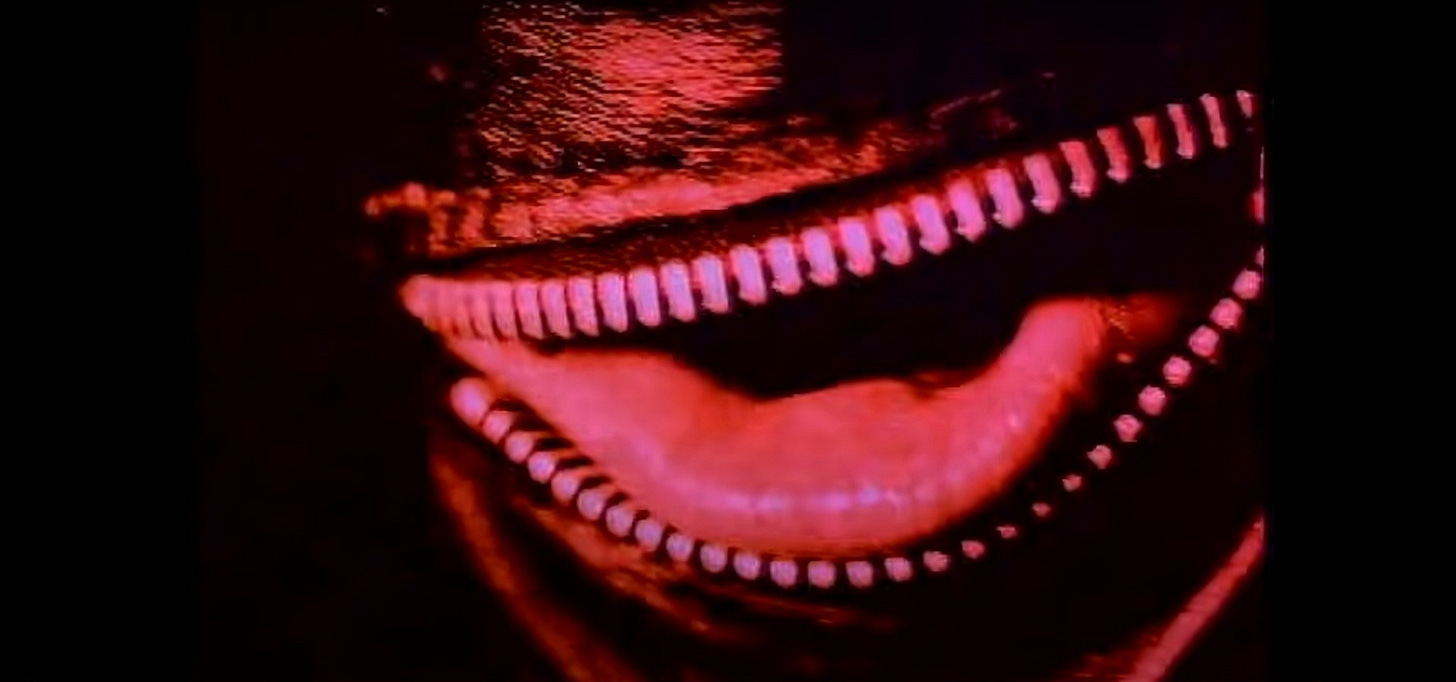

The sound comes as a shock. Instead of a voice, he delivers a breathless jumble of unintelligible words distorted beyond recognition, terrifying and demonic, sounding the way The Kraken would if someone gave the legendary sea monster a microphone. After a few bars, guitarist Trey Spruance slides in and starts tossing out thick, devious riffs. If it weren’t for the song title listed on the 7-inch record, you’d never know that Patton is singing: “Now everybody, have you heard / If you’re in the game / Then the stroke’s the word.”

This is a death metal version of Billy Squire’s 1981 hit “The Stroke.”

As a band defined by a dizzying array of influences, from funk to ska to avant-garde jazz, Mr. Bungle’s choice of covers reflects their earliest influence: death metal. In place of the playful mix of horns and circus motifs that define their debut album, here they redo “The Stroke” in the style of Godflesh, with vocals like Carcass. And it’s this cover song’s loony originality that embodies everything that earned Bungle a cult following. It’s not just a funny experiment. It’s actually good. Every time I hear it, after decades of playing it, I still bang my head to those devious guitar riffs.

People often think Squire’s song is about masturbating, but Squire said ‘stroking’ referred to the way corporate record companies shower musicians with false compliments and overblown praise to do business. Bungle’s warped delivery imbues the benign lyrics with a murderous rage, turning the arena rocker’s weak metaphors into BDSM innuendo that puts listeners on all fours in a windowless basement with a gag in their mouth, like the scene with The Gimp in Pulp Fiction. It helps that Patton sometimes performed this song live while wearing one of those leather gimp bondage masks. Of course, Bungle would cover a song supposedly about masturbation. They’d already written the ultimate jerk off anthem, “Love Is a Fist.”

Clenched emotions / ‘Round my ween / Feel my heart beat / Off and your head in.

It’s adolescent, yes, but the music’s good.

By the time the band started playing “The Stroke,” they knew heavy music inside and out and had written their own nightmarish dirge called “Everyone I Went To High School With Is Dead.” Played with similarly grinding guitar and distorted vocals, maybe the band thought it’d be fun to give something slick the same sludge rock treatment. Or better yet, after Warner Brothers records signed the band, maybe label executives started feeding these young Californians too much of the same saccharine praise that irritated Squire: You guys are so original. You guys are the next big thing. You’re gonna be huge! The band knew they were original but could not have thought they’d be huge. Listen to them. They played ska-funk-circus-metal on an album whose insert features a drunk clown wielding a whisky bottle at a children’s birthday party. If Bungle felt stroked, maybe they decided to make a statement by turning one of the early-80’s biggest commercial hits into the least commercial form they could, killing the music’s mass appeal and reminding Warner Brothers executives who they were dealing with.

“Stroke me, stroke me,” Patton growls. “Stroke!”

They might have also just liked the song. They liked a lot of music.

Someone recorded the band playing “The Stroke” through the Cabaret Metro’s soundboard in Chicago in 1992, and bootleggers released it in Italy on a low-budget limited edition 7-inch record of 500. The band eventually bought as many copies of the record as they could find and sold them at shows in 1995—another highly uncommercial move, though also a great way to shut down bootleggers.

When I played “The Stroke” for my wife recently, she scowled. “I don’t like that,” she said. “Nobody likes that.”

That made me laugh. I liked it! It’s brilliant and way more listenable than the original. As someone on YouTube put it so perfectly: “There is no other band on earth that could / would think to do this.”

Bungle played “The Stroke” at the show my friends and I saw in Phoenix in 1992, but I didn’t recognize it then. I didn’t recognize half the songs they played that night, which I realize now included some of their many early covers: “Time” by the Alan Parsons Project; “Third Floor Dungeon” from Dr. Seuss’ 1953 film 5,000 Fingers Of Dr. T.; Henry Mancini’s “The Thing Strikes Back.” They gave us the songs we knew and loved, but they also kept us guessing, challenging us to hear the simple musical beauty of songs like the themes from the original Super Mario Brothers and Welcome Back Kotter, which they would open a show with and then turn around and play again in Spanish.

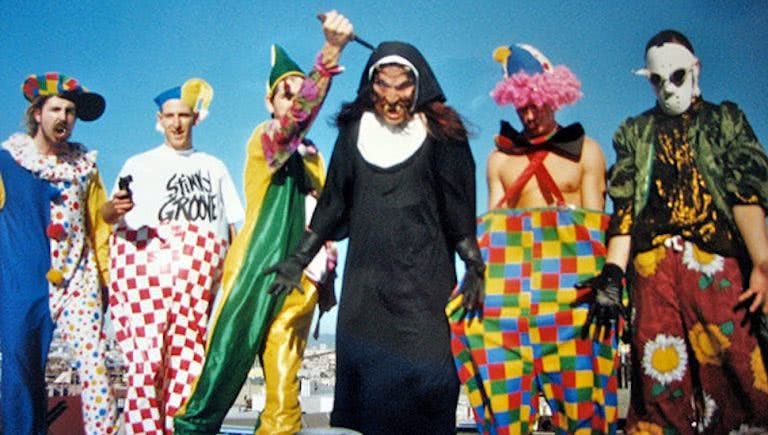

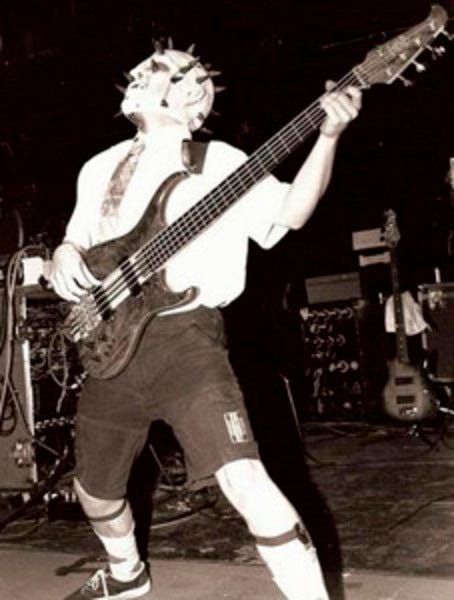

Hearing Bungle’s version of Squire now, nearly 30 years after they recorded it, makes me proud to have seen them play anything during a period when they became renowned for their unhinged performances dressed in clown costumes and rubber masks. Of the hundreds of shows I’ve seen in my life, their 1992 show remains one of the most electrifying and terrifying, in terms of originality and energy. When you’re a kid, rock ’n roll can scare you. You want it to, but scary easily crossed into camp. Bungle never became cartoons the way Danzig’s horror punk did. Bungle seemed genuinely scary, because they seemed unwell, more escapees from the asylum than punks dressed in Halloween costumes, even though Bungle’s were basically Halloween costumes.

It was less how they dress than how they moved on stage back then, which was truly creepy.

When Mr. Bungle’s debut album, Mr. Bungle, came out in 1991, I was a junior in high school. Already a fan of Faith No More, someone told me that the lead singer, Mike Patton, had a new band. It turns out that the opposite was true. Bungle was Patton’s old band. After Faith No More fired their original lead singer in 1988, they hired Patton as his replacement in 1989 because they’d heard Bungle. When I finally heard Mr. Bungle, I became an instant fan and was also confused. Listening, I kept thinking, What the hell is this?

It made me an instant fan.

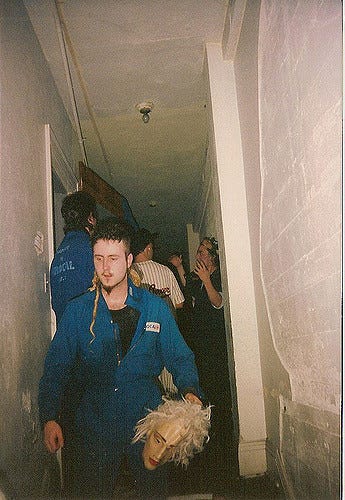

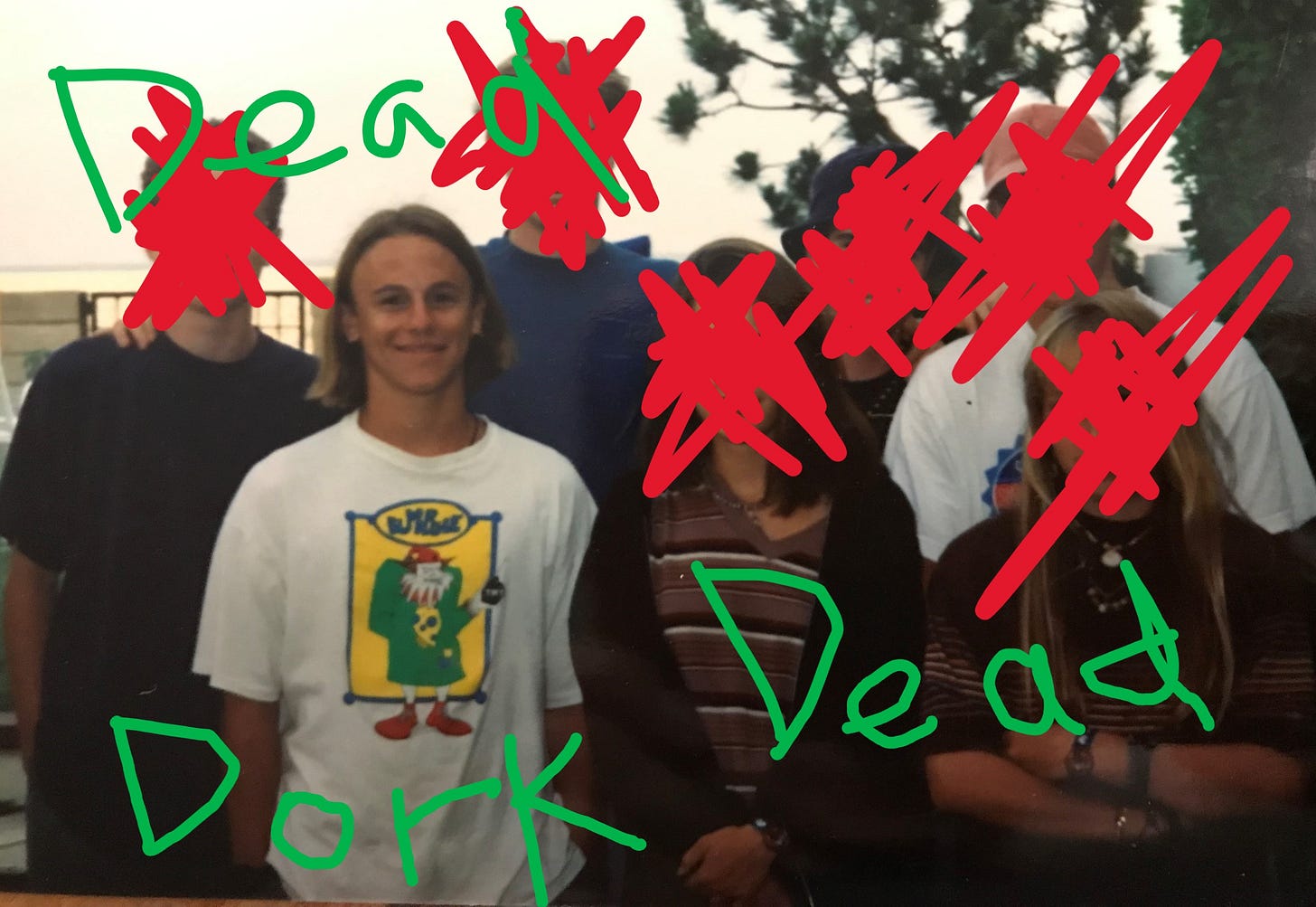

I wore my Bungle shirt everywhere, including this dress-up family dinner in 1992:

Somehow my sweet Jewish grandmother still wanted to touch my shoulder.

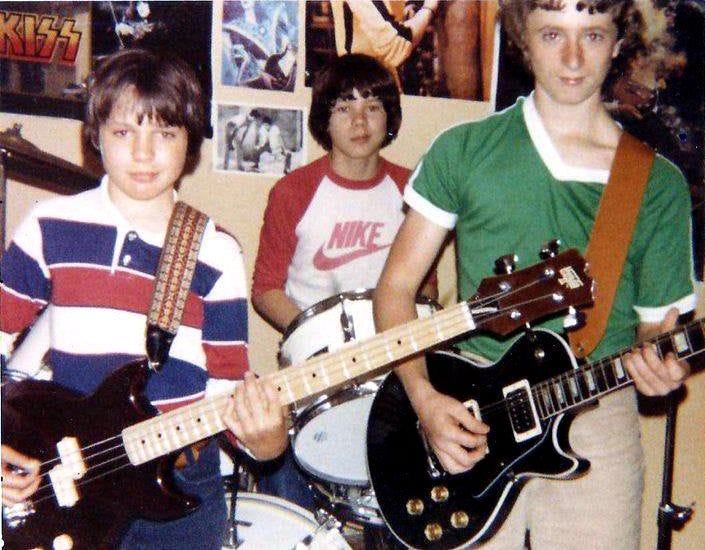

Mike Patton’s group of high friends formed Mr. Bungle in Eureka, California in 1985. Built from the ashes of a series of metal bands, fringe musical tastes and adventurous creativity drew Patton, bassist Trevor Dunn, and guitarist Trey Spruance together in this isolated town of hippies and dairy farmers. As Dunn told one interviewer: “I met Mike in junior high school where we were gradually seceding from our respective cliques (he from basketball jocks, I from D&D geeks) and started trading rock records. I suppose he saw that I was playing in a band and saw something in common between us.”

Dunn had started playing bass in 1981 at age thirteen. When he and Patton met in junior high, they swapped favorite rock records as they drifted from the Dungeons & Dragons nerds and basketball players they each hung out with and drifted towards their new weird center. “I suppose he saw that I was playing in a band and saw something in common between us,” Dunn said. They built a brotherhood around that mutually adventurous sense of creativity.

In 1984, Dunn and Patton joined a metal cover band called Gemini. They performed at that year’s Eureka High Talent Night. Someone filmed it. Dunn is dressed like a Kiss fan, with a hair helmet and straps across this chest. Patton is a head banger with chains draped across this leather pants, but even as a teen, he has stage presence. He’s possessed by confidence, a knack for showmanship—strutting around the stage like he already owns it, kneeling beside the guitarist during a solo. Although his hammy theater geek style doesn’t hint at his future repertoire of terrifyingly aggressive moves, at times he grips the mic with both hands in front of his face like he’d one day grip it while he screamed “Stroke!” Patton always ruled.

While Dunn and Patton were striking their hair metal poses, a fellow freak named Trey Spruance was getting his ass kicked for being an outsider. In 1981, kids all around Spruance’s rural junior high wore AC/DC shirts and got drunk, but Spruance joined the Devo fan club in order to get one of the new wave band’s signature red plastic hats, called the energy dome. When he wore his dome to school, some metalhead bully beat him up and shoved him into a garbage can. “And I think it was at the bottom of the garbage can,” Spruance recalled, “with my face, like, in the garbage, when I realized I had to be a musician. ‘Cause I was gonna get those people back somehow. I went through a period where I thought I would probably be a serial killer, or something like that. It made sense. I became like, an environmental terrorist for a while, too. But music was going to be the career for me, ‘cause environmental terrorism is effective in some things, but it’s not so effective in others. And being a serial killer doesn’t really do anybody any good. So, my choice ended up being music.”

Spruance’s junior high was way out in the economically depressed countryside, where a struggling logging and fishing industry had left many families destitute and their kids angry. Students didn’t like Trey’s or his brothers’ velour shirts or proper English, so they repeatedly beat up the Spruances up. Trey’s brother got harassed so badly that he ditched half of the school year. “You wouldn’t even call it ‘bullying,’” Spruance said years later. “Kids were hanging cats from ropes and cutting their bellies open and flinging them around like a helicopter so their guts would fly out all over the basketball area. Hijinx like that were pretty everyday there.” As an adult, he sympathized with logging families’ lack of prospects, but the area’s grisly vibes and violence still haunted him. A future band mate of his, John Law, grew up a block from that school, and a man got both of his hands cut off and face peeled clean of skin right in front of Law’s house. Fortunately for Spruance, authorities closed the school, so he transferred to Eureka, and the bullying ended.

“I met Mike and Trevor a few years later under very different circumstances at Eureka High School,” Spruance said, “a comparative paradise.” For years the school building still sat vacant outside Eureka, which pleased him to see. It seemed like retribution, though it couldn’t erase him traumatic memories. He had terrible memories. That macabre period reappeared in his music as comic death metal with scary circus elements.

In town, with his Beach Boys records and Devo hat, Spruance started playing an instrument and continued discovering new music. He joined high school jazz band and an experimental death metal band called Torcher at age 15. “We had this idea that we were going to play a bunch of ska tunes for a bunch of metalheads,” Spruance told The Georgia Straight, “and that’ll be amazing. Half of the audience hated us, but there was definitely a joy in confronting that wall between styles.”

Back then, you were either into metal or punk. You couldn’t like both. Things were so siloed in the 1980s, unlike the way they are now. Jocks harassed “freaks,” and you were one or the other. As Spruance broke the code in his band, Dunn and Patton broke the code in their metal band Fiend. The weird brotherhood encouraged the other members to mix some thrash songs by D.R.I. and Corrosion of Conformity into their Slayer- and Metallica-heavy sets. The band treated this as heresy and kicked the two out for trying to make the band too punk, and also for wanting to change the band name to Turd. “That division always seemed ridiculous to me and still does,” Dunn said. “Trey, on the other hand, couldn’t find an apt bass player for his weird, harmonically adventurous metal band ‘Torcher.’ Thus, we gravitated toward a central unit.”

Genre distinctions meant nothing to them. They liked what they liked, and everything could potentially blend into the other. It’s that philosophy that came to define Bungle’s sound as Patton and Dunn found other people who shared their eclectic taste.

Dunn and Spruance got to know each other in musical theory class and the school’s jazz big band. After Spruance introduced him to Poulenc’s Organ Concerto and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, they played together in the school’s big band.

“We certainly encouraged each other,” Dunn said later, “even into our college years and beyond (not just in music but also in literature, art and general discourse). We were all fortunate enough to be blessed with curiosity. …The eccentric quality seemed natural to us, it wasn’t forced.”

Freed from the tyranny of genre and close-mindedness, the boys started jamming together and sharing records, creating their own world. “The other thing is that Mike and Trevor were pretty well-adjusted and well-liked by their peers,” Spruance said. “Prior to high school I had a really different experience than them.” People in high school liked Patton, but ultimately, all the boys’ musical tastes and expansive ways of thinking made them outsiders, so they hung out with each other. Social isolation fused them further.

“Once Trey, Mike, Jed and I got together (’84 or ’85),” Dunn remembered, “it was pretty much unanimous to start a band. I remember our first session being a haphazard jam of various metal covers such as ‘Whiplash’ and ‘Chemical Warfare.’ We contemplated naming the band Summer Breeze for a moment. It seemed like the most un-metal thing we could imagine.”

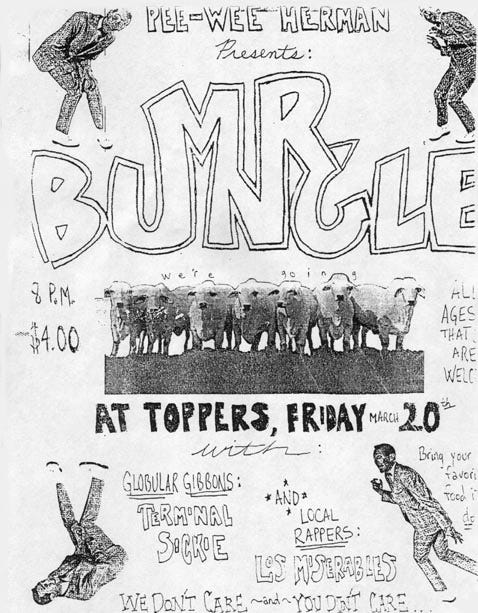

They named their new band Mr. Bungle, after a character in the educational children’s film Beginning Responsibility: Lunchroom Manners from 1951. The was designed to teach kids hygiene and good manners. Mr. Bungle was the main character, a puppet who always caused trouble, representing the impolite, dirty, uncouth kind of person it warned against becoming. The 1981 HBO special The Pee-wee Herman Show included Beginning Responsibility, the band later sampled audio from the show between their songs “Love Is a Fist” and “Dead Goon.” I guess the band ran against the conventional grain of polite society the way the puppet did. And bam, they had a name.

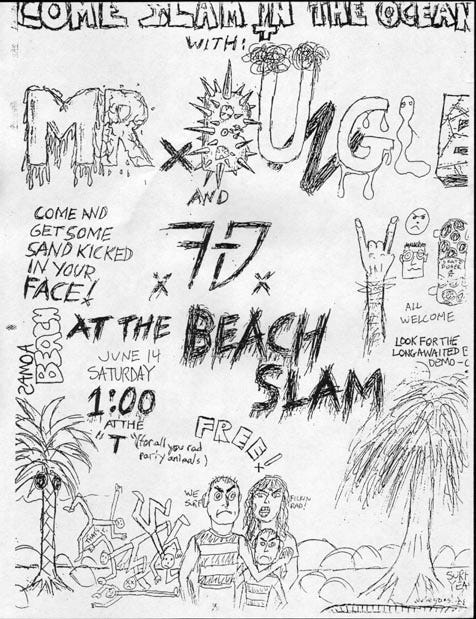

In November 1985, a year after Gemini played those metal covers, the guys had shape-shifted and played their first show as Mr. Bungle at the Bayside Grange off Highway 101. Soon after, they played at Eureka High School in 1985. As Spruance played “Chopsticks” on guitar, Dunn played bass upside on his back, and two kids on skateboards rolled Patton on stage, where they continued to jump around and skate, skidding and doing spins and falling as the band played.

Back then, before the internet, Eureka was a bubble. Perched between the frigid Pacific Ocean and Highway 101 on the northern California coast, Eureka is shrouded by fog, hemmed in by redwoods and dairy farms, stinking of manure. Bungle developed their repertoire and lunatic sound in this isolating cocoon. As Dunn put it: “I would say that every song reflects, in some way, our collective introspection, confusion, disdain and resultant social commentary and self-reflection that developed as teenagers in the ’80s. While many of our peers were turning to drugs and alcohol, we found comfort in music.” Which is funny, because when you listen to their music, it’s easy to think it could only result from drugs, mental illness, or alcohol. The complete opposite is true. These are talented musicians, wildly imaginative and experimental, and they play technically difficult music. Yes, it’s difficult to listen to, too, as frenetic and mashed-up as some of it is, but playing it requires clarity and vision. Not surprisingly, they outgrew their tiny hippie dairy town fast.

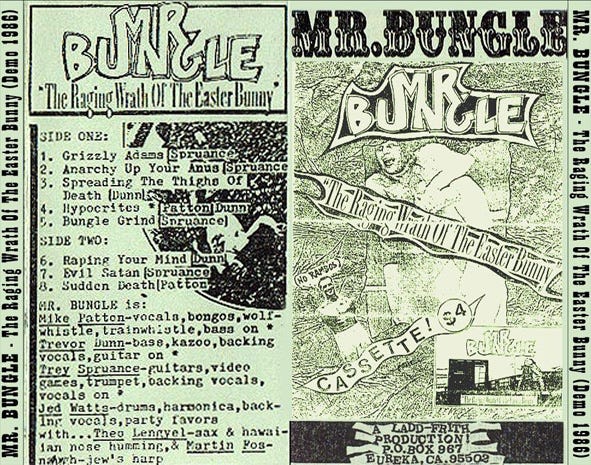

What became their first demo, The Raging Wrath Of The Easter Bunny, came out in 1986. The 16-year-old Trey recorded it on his Tascam four-track at home, which they listed on the tape as F.O.S. Studios (meaning, “full of shit”), and he mixed it during Easter, hence the name. They tried to release it in April, but production took more time than they expected. It featured original songs like “Anarchy Up Your Anus,” “Spreading The Thighs Of Death,” and ‘Bungle Grind.” Although they retired these early songs as they wrote new ones, the album itself contained many of the musical influences and design aesthetic that would define their first commercial album, namely, armless torsos and creepy photocopied images pasted together like a ransom note. Clown murder, beheadings, sharp blades, John Wayne Gacey—that would come later. They also figured out their logo by 1986, when it appeared on the demo’s cover: the words stacked on top of each other, with the legs of the M running into the top of the U, and the R into the N and G.

The Times Standard newspaper, which covers Humboldt County, covered Bungle back in 1986. “…Patton says Mr. Bungle’s new music is ‘funkadelic, thrashing, circus, ska,’” the paper wrote. “The band’s new direction is more challenging to Patton. ‘Now I actually sing instead of vomiting.’…The young, outspoken bandmates describe their old music as ‘speed-thrash metal,’ ‘music to fight to,’ and ‘a fast cartoon.’”

“Our first demo was total death metal, basically,” Dunn told Decibel. “But at the same time, we were all interested in different kinds of music. Trey and I were checking out jazz and classical. Patton was into all kinds of different stuff, too, and eventually we got burnt out on metal and started doing other weird stuff.”

A local dude named Brian Ladd offered to help with the tape’s artwork and marketing. He played in the band Psyclones, helped run the local Ladd-Frith label, and he liked the Bungle shows he went to enough to help out these strange teenagers.

The band sold copies of Easter Bunny for $4 apiece, by mail and in a few local record stores. The band played a few shows, but they were in high school. They mostly practiced after class, creating their own parallel universe of weirdness, with their instruments as a forcefield to repel Eureka’s ugliness. When they graduated, they started college at Humboldt State and kept playing.

Important things were happening to the south that would change their musical careers.

On October 4, 1986, eighteen-year-old Mike Patton and Trey Spruance drove to Humboldt State College to see Faith No More play in a pizza joint. Five hours north of San Francisco, the northern California country felt so far away that FNM drummer Mike Bordin said the gig was “Literally so far out, it was almost in Oregon!”

“There were six people there and three of them were my friends,” Patton remembered in the band biography, The Real Story. “It was really bad,” Patton said, “a really pathetic show and I remember them standing around the van really upset. [Drummer] Puffy was really uptight wanting to know where to get weed. Nobody was talking to him, I think he asked us because we were just hanging around.”

Drummer Mike Bordin’s childhood afro earned him the nickname Puffy. What Patton didn’t know was that internal problems between Faith No More’s members would soon lead to them ousting singer Chuck Mosley, and they’d need a new singer to fill the vacancy.

Milling around under the cold, moist Eureka sky after the show, Patton wanted to give Faith No More a copy of their demo, The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny but hesitated. Spruance encouraged him. Spruance was the person who convinced him to come to the show in the first place. Patton didn’t like FNM’s first album, but Spruance do, so they came.

Talking by the van, Spruance thanked Bordin for playing up there and apologized for the low turnout. College wasn’t in session, Spruance explained. The students were on vacation. Patton gave Bordin the tape. The band was probably like, Thanks kid, we’ll check it out, then marveled at the blurry photocopied green and black cover that looked like another crap demo from a teenage band. Bungle had played this pizza parlor a few times, but Bungle was one year old. Faith No More had released its debut We Care a Lot the previous year on a major label and would release its next major label album the following year. Here they were, hyped and ready to embark on a national tour, and playing an empty pizza joint. “But their situation then never even registered with me,” Patton said, “touring was unreal, Warner Bros was like a Tom And Jerry cartoon. At that time I didn’t wanna know about any of that shit. I gave them a tape and told them, ‘This is what music from around here sounds like, from this region.’”

Bordin liked the tape and shared it with the rest of the band back in San Francisco. Keyboardist Roddy Bottum hated it. Guitarist Jim Martin liked it because it was thrash metal. In fact, once Martin heard it, he told the rest of the band, “This guy has got to be this giant fat guy with all the power that he’s got in his voice!”

Even at his young age, Patton’s voice stood out.

Mr. Bungle never heard more from Bordin, and Bungle went back to their random rehearsal spaces where they recorded new songs on Trey’s four-track. They recorded their Bowl of Chiley demo in 1987, which someone illegally leaked as a misspelled bootleg.

“After about a year we got tired of playing speed metal and wanted to do something a little more creative,” Dunn told Sounds magazine in 1991. “So we just stopped and started writing our own style of music, which was influenced by bands like Camper Van Beethoven, Oingo Boingo, Bad Manners and kind of ska funk-ish oriented stuff. Then we added a two-piece horn section and a new drummer, so now we don’t really have any kind of limit on the music we play.”

Trevor worked at a pizza joint at the time. Patton worked at a record store while earning his English degree. They sold their demo cassettes at shows and through the mail. This fed the buzz. Their range of personas was even vast back then, moving from song titles that were menacing (“Evil Satan”) to cryptic (“Definition of Shapes”), adolescent (“Fart in a Bag”) to playfully sweet (“Hi!”) in the span of a single tape. It’s hard to picture kids in Arcata blasting “Evil Satan” in their dad’s pickup truck and not getting weird looks.

In 1987, the year after the pizza parlor show, the Bungle boys drove to San Francisco to see Faith No More open for the Red Hot Chili Peppers at The Fillmore. Patton took a copy of their new demo, Bowl of Chiley, to give to drummer Mike Bordin.

“So this tour comes to San Francisco and we’re playing The Fillmore,” Bordin remembered in Noisy, “and I see Mike Patton. So I go to him, ‘Hey, Jim really likes you and you should sing in our band.’ But then Mike says to me, ‘Oh we don’t sound like that anymore.’ So he gives me another demo tape, which was Bowel of Chiley, and it was like fucking Madness meets James Bond. It was this secret super spy ska music, and it was awesome. And I was like, ‘Oh dude, I’m so glad you don’t sound like that anymore, because who wants to be one dimensional?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, man.’ That was the one thing that gave him maybe even a second of thinking about joining our band, that we would be available or open to evolution. Because I didn’t say, ‘Oh fuck that, you gotta sound like The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny, because that’s what you do!’ I just think in that regard right there, that’s really the thing that happened with Mr. Bungle. They evolved, and we applauded it. Well, three of the four guys in the band applauded it.”

“I remember it was one of our first San Francisco experiences,” Patton said, “y’know, ‘Oakies go to the big city’ thing. It was a fuckin’ nightmare! We were gawking around like we were on Mars. We were going to a big show in the city, we were driving, no parents, no chauffeur, and we parked right outside The Fillmore in an ugly neighborhood. We came outside after the gig and our tire had been slashed. We were staying with Trey’s grandparents, who were preachers, so we changed to the spare and drove to his grandparent’s place, left the car and decided to deal with it the next morning. Where we came from, you parked where you wanted, but I guess we’d parked in someone’s driveway and the car was gone. So we thought, ‘someone’s stolen our car!’ God-fuckin’-dammit, we hated the place, we hated the people, we just wanted to leave! We called the police and they told us to try City Tow, which we didn’t understand. What had we done to anyone? It was, of course, there and the tire had gone flat again. They wouldn’t tow us to a service station. They just wanted us out. We found a tire place nearby and just got the fuck outta there. I remember we were just yelling at people, yelling anything at them ‘YOU SUCK!’ We were driving across the bridge, all bummed out. And I looked over to my right and in this BMW was a businessman jacking off! He was waving his dick at us, grinning, and it was like, ‘FUCK! LOOK AT THAT FUCKING GUY!’ We were his stimulus, young country boys! We got the full city treatment.”

Back then they rehearsed inside a chicken coop with four- to five-foot ceilings. Talk about country boys.

Nowadays young people are savvy. They know how to promote themselves. They’ve seen enough biopics to know how important it is for your career to get your music in the right hands at the right time, that networking is okay and that you can never give your stuff to too many people or have coffee with too many future connections. Patton wasn’t thinking like that. “I suppose I was just living a miserably content life,” he said, “knowing there was nothing I would be able to do about it and not willing to go out of my way to change it at all. I never thought or planned anything l never looked through any ‘big windows’ like that. Even now I don’t. I think it’s a big fuckin’ mistake. I don’t WANNA know!”

When FNM fired their original singer, Mosley, they auditioned potential lead singers, and guitarist Jim Martin told the band, “Let’s get that big fat guy from Mr. Bungle!”

“He was such a ridiculously good singer,” Bordin remembered.

Keyboardist Roddy Bottum said, “We wanted someone that had a really good voice and a lot of energy.” Bottum hated the music but loved the singer’s range and respected how uncommercial this “total psycho-maniac band” was.

So Martin called Patton.

“Then one day I get this call from this old-man-sounding guy,” Pattom remembered. “‘Hey man, wanna come down and jam? This is Jim from Faith No More.’ I just really resisted at first, I was really flabbergasted, like, ‘Wow, I can’t do this’ I wasn’t in a situation that I wanted to change.”

“We called him and told him to come down,” said Jim, “we wanted him to go to work immediately. He was very hesitant, like: ‘I can’t do this right now; it’s not a good day. I have a school box social to go to. And tomorrow is show and tell. If I had plenty of advance warning, I might be able to come down for a little while, but today is not good.’ I told him he was at a crossroads in life: one way was to become a singer, the other way was to be a record store clerk in a shitty little town in Northern California. He really was like that. Very clean and shiny, nice kid. Milk and cookies type.”

It’s hard to imagine a guy who would one day snarl “The Stroke” in a bondage mask ever being all milk and cookies, unless he was pouring the milk over a mutilated clown corpse for breakfast.

Patton stayed resistant. Then Bordin called.

“Yeah, Puffy called,” Patton said, “the band diplomat. And I think the reason I did it was opportunity, to have a laugh, I’m not sure. I know my first reaction was ‘I can’t.’ I was going to school, I was in a band, maybe I could do it on my summer vacation, but I didn’t want it interfering with what I was doing up there. As I remember, Puffy was greasing me in a peculiar way like, ‘We really like your tape and we’re thinking of a couple of guys, maybe you could come down and practice.’”

When the call ended, Patton called bassist Trevor Dunn: “It was like someone calling and saying, ‘Hey wanna work in the mail room at The White House. Yeah right what are you talking about?’ I was very negative towards the idea. But l knew the band and knew there was no way I could fit into that scheme of things. I liked their second LP, but the first one was just bad hippy music. I hated it. The guy who egged me on to see them was Trey, who really liked their first record. And somewhere along the line I thought it wasn’t going to hurt to do this. I felt it’d be an interesting musical experiment, it was two separate worlds. I didn’t want it to be an audition thing though, ‘here let me sing your songs.’”

Patton wanted to get finish college and earn his degree. He was enjoying the direction his band was going. “I didn’t see Faith No More as some yellow brick road to success or failure anything,” Patton said. “I just thought I would try it. The music wasn’t quite what I was about at the time, but I took it as a challenge.” But his Bungle bandmates encouraged him, saying, “Just do this. It doesn’t mean you have to leave our band.”

Unlike so many bands riddled with in-fighting and egotism, Bungle’s members were close friends who encouraged and appreciated each other. For how psychotic their whole look was, Bungle was actually filled with—gulp—love.

“At the time Mr. Bungle was just a garage band,” Dunn said. “We played a few shows in town, but none of us had any great visions of being rock stars. We knew our music was weird. But Faith No More was hardly known at that time as well. They were a local band in San Francisco. They did have a couple of records out, though. And the idea of being in multiple bands was nothing new to us. I quit working in a pizza joint so I could join a local bar band, which ended up being my job all through college. So, joining Faith No More was just a great opportunity for Mike. We were all fans of theirs, so the rest of us were excited about it.”

To calm Patton’s nerves, Trevor and Trey drove to SF for the audition with him. “He [Trevor] was laughing at me singing,” Patton said, “he’d never heard me ‘sing’ before because all I ever used to do was scream. Which is, funnily enough, what they hired me for. That was the only thing they’d heard. If I was to take out an ad, all that would be on it would be ‘growling, shouting.’”

Patton was their first audition.

“It ended up being OK,” he said. “They’d play me this riff they were thinking of and just ask me to sing something with it. So I’d just start singing something that came into my head. It was hard to say whether it was good or bad, but it turned out to be a positive experience. I had, up to that point, never played with anyone else in my life. It was like having the same girlfriend for 20 years and all of a sudden seeing someone else too. So anything that was different, for better or for worse, was certainly eye-opening. But I don’t think it went particularly well or anything. Let’s face it, Mr. Bungle cannot write songs. We’ve never been able to write songs. Everything we’ve ever done has been like LEGOS, whereas their stuff were real songs, verse/chorus, structured, rock music. It was so weird to me. So for me to try and sing in that way was funny and challenging at the same time.”

FNM jammed with four or five other applicants afterwards, including Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, but they always knew Patton was their guy. As Jim put it: “[It] was pretty clear that Patton had superior natural ability.”

“I was against the idea,” FNM bassist and founding member Bill Gould said in The Real Story biography. “But then he came down and tried out. We told him to just sing with our music, whatever the first idea off the top of his head was to just sing it, and he had a million ideas. He totally understood what we were doing in a real physical sense. He took cues off the music and sang over it. We tried out a few other guys, but he was the one, although I felt a bit guilty about it. Guilty because it seemed too easy. It seemed like he was gonna get exploited to death; a young innocent with long hair. Too easy to sell! But he could sing, he knew what we were doing and he was the most natural choice.”

Patton couldn’t believe that Jim liked his tape. When he got to know Jim as a band member, it only amazed him more. “It always kinda makes me wonder,” Patton said, “because he likes maybe five or six bands in the whole world. So why would he like Mr. Bungle ever in any form? It may well have been savage tape, but the world is filled with savage music so why would he like this one? I always wondered about that, right to this day. How does Mr. Bungle fit in with Pink Floyd, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, the Dune soundtrack, the Platoon soundtrack and Celtic Folk music? I don’t get it, although it was obviously some weird misfortune, a twist of fate.”

As Faith No More entered their second phase as a commercial band, Mr. Bungle kept recording new songs. Their third demo, Goddamit I Love America!!!$ɫ!!, came out in 1988, featuring songs like “Egg” and “Waltz For Grandma’s Sake.” By then they’d found their sound, a complex fusion that one flyer described as “funkadelic thrashing circus ska.”

“The thing is, every now and then while driving around aimlessly as teenagers blasting Sodom’s ‘Obsessed by Cruelty’ album at 3AM,” Spruance remembered, “Patton and I would run across these redneck carnivals popping up overnight on the periphery of town, in the middle of nowhere. We called them ‘Satanic Carnivals’ due to their unexplained phantasmic arrival, and their pointless neon lights no one was around to appreciate as they sparkled up against the dreary fog. The next night, when they’d be open, we’d actually go to these god-damned things. There was certainly a malice to the toothless meth-heads running the barely-functioning rides, and the fights that would break out among drunken loggers and various shades of hashers could get pretty dark, but it was all pretty standard fare—no evil clowns.”

Still, Bungle’s clown phase had begun.

To promote their new tape, they did an interview for a radio show called For Locals Only, on Humboldt County radio KFMI.

To promote their tape, they also recorded a 1988 show to broadcast on the radio.

“Snap, crackle, pop!” Patton sings over ska music. “I’m addicted to a breakfast cereal!” They also played a crazy cover of GNR’s “Welcome to the Jungle.”

Of-stage, they practiced wherever they could.

“One of those places was ‘The Chicken Coops’ out in Manila,” Dunn remembered, “which is a frightening little ‘beach town’ of white-trash hillbillies. My dad used to work at a lumber mill out there. The place was literally an old, abandoned chicken coop with ceilings about 5 1/2 feet high. It was rented by a weird family who used to send their half-wit, stuttering son out to collect the ‘went money’ from us. The song ‘Dead Goon’ was conceived, almost in its entirety, from a free-form jam session one cold, damp night in those coops. We also used to rehearse in the big band room in the music department at HSU. We would drive our cars right through campus up to the music building and rehearse until wee hours of the night, long after any piano students had finished with their Beethoven sonatas. There was a creepy custodian who worked nights we liked to call ‘The Metal Janitor.’ He looked like a cross between John Oats and Charles Bronson with a handle-bar mustache and leather jacket. He would peer at us for hours through a small square window in the door and watch us practice. We tried to pretend he wasn’t there. I specifically remember working on ‘Stubb-a-Dub’ in that room. We also started working on an instrumental tune called ‘Captain Asshole’ that never saw the light of day.”

To make some money on the side, Dunn also played in a shitty bar band, and the experience led to the lyrics for “Waltz For Grandma’s Sake” and “Slowly Growing Deaf.”

“I got a lot of inspiration from bar hags,” Dunn said. “‘Slowly’ was inspired by the ironic need to wear earplugs while listening to music and also people’s inability to listen.”

Bungle also rehearsed at their drummer Danny Heifetz’s house in Arcata. “It was a house full of college students or people that had graduated already and were just hanging around,” said Dunn. “Anyway, Danny had an old reel-to-reel 4-track machine and we made a demo there once called ‘The Tape’ that included early versions of ‘Platypus’ and ‘My Ass is On Fire’ and the Mario Bros video game music. Once, the rest of us overstayed our welcome after practice so Danny shit into a Styrofoam cup and chased us out of the house with it.”

In 1989, they recorded their fourth demo tape, OU818, at Dancing Dog Studios. This tape contained a lot of what they’d include on Mr. Bungle and helped them further refine their unique sound and stage presence.

“‘Mr. Nice Guy was probably my favorite song on OU818,” said Dunn, “but for some reason it didn't make the cut for the CD. We also recorded ‘Platypus’ and a cover of ‘Thunderball,’ neither of which made it on to the album.” David Bryson, the studio’s owner, engineered the session. “He was a decent engineer and put up with our shit, so we asked him to work on the CD.”

Even at their young age, they were on a creative tear.

When Bungle released OU818, Patton was officially Faith No More’s their singer. Two weeks after joining, he’d written all of the lyrics to their next album, The Real Thing. When the record came out in June of ’89, it became a huge hit. No longer just a longhaired freak in a cow-town playing thrash about feces, Patton was now all over glossy music magazines, jumping around in Faith No More’s “Epic” video on MTV, and opening shows for bigger bands in huge venues. It’s what he’d been training to do since strutting around that high school talent contest in 1984. Wisely, he made sure to use the opportunity to publicize Mr. Bungle: He even wore his Bungle t-shirt in the “Epic” video, which played constantly back then. The “Epic” single went gold in 1990.

When FNM signed to Warner Brothers, they had built a big Bay Area following. And that relationship helped grease the wheel enough for Warner Brothers to sign Mr. Bungle, too.

At the time, Warner Brothers was signing underground bands that had little to no history of mainstream record sales, and they Warner a reputation for taking risks on artists and taking time to grow with them. They’d signed X. They’d signed Devo, Hendrix, and The Talking Heads, and they let Husker Du produce their own two records. Before alternative music went mainstream in the early 1990s, Warner Brothers was the corporate label that supported innovative bands who were ahead of the curve. Signing Bungle was also a sign of the times.

As underground music started to creep closer into the lucrative mainstream, corporate labels quickly recognized that they no longer knew what would sell in the alternative era. The audience was changing. The old way of doing things eventually stopped worked, so labels started signing everyone, throwing money at weirdoes and copycats as well as at originals, to see what resonated with consumers. Was it Pixies? Was it Primus? Pere Ubu, Mekons, The Cure, Ian McCulloch, or Tragically Hip? Bungle was an experiment. But still, some doubted that any label would have taken a chance on a band like Bungle were it not for that relationship with FNM.

“Under normal circumstances,” The Los Angeles Times wrote in 1991, “you’d have to describe Mr. Bungle’s chances of landing a major label deal as... a long shot.”

“There is no denying that we were handed an otherwise unlikely opportunity,” Dunn told the Faith No More Followers website. “We were certainly looking for a label at that time and I doubt that, if it weren’t for that FNM video in which Mike wears a Bungle t-shirt, no one would have been interested or curious about us. We may or may not have continued on depending on how difficult it would have been without that hype. It was a golden chance to make the records we wanted with a real budget from a label that had no interest (i.e no meddling) in what we were doing.”

Still, can you imagine what those corporate board meetings sounded like? “Hi Bob, I read your proposal about this Bungle group and your projections. The demo is... strange, yes. But original. I think they’re on to something different. The tide is shifting from Van Halen and Warrant, and we need to get on this new ‘alternative movement’ with the severed heads and mangled clowns. I think ‘My Ass Is On Fire’ has potential. But is there a song on the album that could get radio play beyond college stations? I don’t think ‘Love Is a Fist’ will do that. I mean, everyone masturbates, but still.”

The FNM experience taught Bungle an important business lesson: The more bands you’re in, the more income you have, and the more visibility. Each band can feed the others, and the feedback loop feeds you. Most band members played in other bands on the side to earn money. And to succeed in corporate America without sacrificing their unique musical vision, they recognized that he had to work extra hard. Plus, with Patton’s range of musical interests and voices, he learned to have many outlets to express himself. Bungle and Faith No More were very different entities with different fan bases. Later Patton expanded further, collaborating with different musicians to form other bands such as Tomahawk and Fantômas, producing albums and doing one-off projects and recording with artists like Bjork. He embodies the term workaholic, thankfully, because he has a lot to say.

Now that Bungle had material and a big corporate budget, they needed to find a suitable producer for their debut. Who was on their warped wavelength enough to bring out their best? They wanted Thomas Dolby or Frank Zappa, but one was too expensive and the other too busy. So Spruance approached John Zorn in San Francisco.

“We were all appreciative of Naked City, Spillane and Spy Vs Spy—Zorn’s projects of the late-80s that found their way onto the Nonesuch label,” Dunn said. “I think it was Danny and Trey who approached Zorn when he was in SF and handed him a cassette tape of some songs and improv sessions we had made in Eureka (the “legendary” Chicken Coop Sessions that were recorded in an actual chicken coop with 4-ft ceilings where we used to rehearse). He tried to convince us that he wasn’t ‘commercial’ and we might find a more apt producer somewhere else, but we were persistent as we felt that—due to his understanding of many genres—that he would understand us.”

With Zorn on board, they’d found one of the few professionals who could actually capture their essence while helping control their chaos.

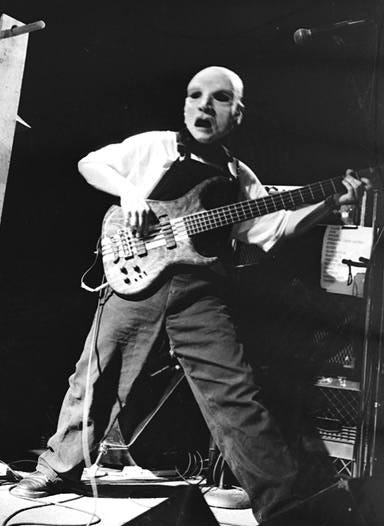

The band recorded live in the studio, then, once they had the drum track and sometimes the bass, they rerecorded the individual instruments around the rhythm section. After that, they added layer upon obsessive layer in post-production. Most bands spend as much time recording their album as Bungle spent in post-production.

Zorn’s schedule kept him from the recording sessions, but he came to mix the album.

“We mixed one song per day,” Dunn said. “Zorn and Bryson would set up a mix and then we’d show up in the afternoon and put in our two cents until we were happy with it. We did some additional recording then as well: Zorn had us use a real B-3 organ, brought out David Shea to add some turntables and got a great solo out of Bar. We forced Zorn to play a solo on ‘Love is a Fist.’”

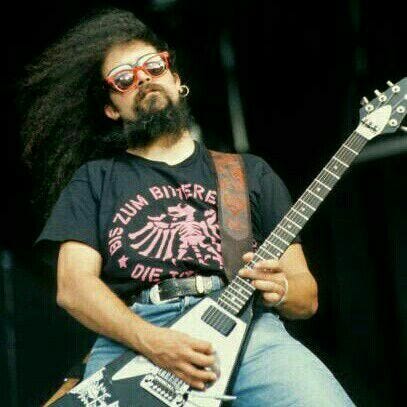

“I had only one amp, a shitty little Peavey ‘Renown,’” Spruance remembered. “So both heavy and clean parts were initially tracked on that. When Zorn came in (he came in at the mixing of the record, to our elation), and heard the pathetic heavy guitar tones we’d done ourselves, he rented a Marshall halfstack on the spot and made me re-do all of the heavy guitar parts. That was a great move. I’d never even really seen a proper ‘heavy’ amp in real life at that point, much less plugged in to one. From that day forward, even up to the present, I get more juxtaposition out of an A/B box switching between a dirty and clean amp than you could ever get with even an infinite chain of effects.”

Just as important, Zorn made sure they didn’t get lost in post-production and kept their adolescent impulses in-check.

“Later, he had us re-do some things and gave us a general guidance,” Dunn said. “Essentially he put the brakes on a bunch of hyper and overly-excited small town kids who tried, almost successfully to fill up every nano-second of space will some kind of sound. He kept us true to our spirit, however, always deferring to our desires, which was encouraging.”

“This is the first CD I was ever on,” said Dunn. “I was 23 and still lived at my parents’ house when we recorded it. That’s kind of embarrassing.”

By the time Warner Brothers put Bungle in the studio in 1990, they’d written most of the album. They’d written “Carousel” and “Egg” in 1988. Thinner versions of “Squeeze Me Macaroni,” “Slowing Growing Deaf,” “The Girls of Porn,” and “Love Is a Fist” appear on their 1989 cassette EP OU818. They’d refined “Carousel” on two different demos, but every song really grew into its own when they recorded them in a proper studio on Warner’s dime.

“Parts of ‘Egg’ and ‘Girls of Porn’ were conceived in my bedroom with Mike and Trey playing guitar and me on bass,” Dunn wrote on his website. “I was about 19 then. I played in this horrible bar band, so I never got to hang out much on the weekends. The three of us would jam for a while, then I’d go off to my bar gig and Trey and Mike would go vandalize various parts of the town.”

They wrote “Stubb (A Dub)” about Spruance’s dog, Stubb, who was dying. For all the album’s ultra-violence, this song contains moments of surprising tenderness.

Do you remember

We called you puppy?

Now you’re one of us

We call you family

But only moments. The song quickly resumes its scatological, comical exploration of life:

Dog Rastafari, do you know

That you’re a fucking dog?

If you can hear me, then throw up

Give me a sign

And I’ll throw a stick, bring it back

Roll over and die

You taught me a lesson. Thanks mom!Do you understand me

Do you think about me when you’re peeing?

Do you really think you’re gonna grow

Into a human being?This dog has seen better days

You’re gonna die

How does it feel, Stubb?

“That picture was taken about 25 yards to the west of ‘Butt Hill,’” Dunn told one interviewer, “where Stubb would wipe her ass. She would start at the top of the hill, grind her butt on the way down the hill and be turned around by the time she got to the bottom, so she could walk right up back to the top and do it again... endlessly. It was so perfectly choreographed and orderly, graceful almost.”

It’s a weird song idea, but lyrically and musically, it’s inventive.

The band always wrote collaboratively. No one was the songwriter, and no one’s ego dominated the publishing rights. One member might write a nearly finished song, like Dunn did with “Egg,” but other members would add to it. Mostly, people brought ideas and riffs to practice or on tape, and the band merged them together. When Patton said Bungle can’t write songs, they made things out of LEGOS, this is what he meant. Their songs were modular. Everyone added blocks to the construction, often too many.

Mr. Bungle called their strings of combined riffs ‘snakes’ and their abandoned ideas ‘graveyards.’ “The trick,” Spruance told one interviewer, “was always in the morphing of complimentary riff ideas that came from different worlds into a coherent song. From this first record, ‘Dead Goon’ is a good example of a song where riffs from everyone in the band were worked together into a song. ‘Dead Goon’ concluded with a recreation of a collective improv we’d done at some earlier point. That process was a bit unto itself, actually. The truth is that there was almost always a different writing process for each song we did.”

Dunn called “Dead Goon” one of the hardest basslines he’d ever learned. And that was partly because a bassist didn’t write it. Their drummer Heifitz did!

“Dead Goon” is also possibly the world’s only song about autoerotic asphyxiation, not that the world needs two.

The song “Carousel” has a scary carnival theme, so it seems like the ultimate embodiment of this Bungle era:

If you want to know what’s behind the show

You ride my carousel and enter life’s jail cell

Love and blood begin to meld, you’ve lost the self that you once held

Merry go round your head, awake, asleep, alive or dead.The clown that painted a smile on you

Is now the one unmasking you

Animated scenes unwind

Dormant figures come to life

That’s a fun song. It takes the psycho Eureka experience to its furthest extent. But for me, “Travolta” epitomizes early Bungle.

“All behold the spectacle,” Patton sings, “a fleshly limbless rectangle / Sitting on a pedestal / so nasal-handicapable.”

It reads as beautifully imagined nonsense, and it’s pure lyrical gold. But how did this relate to John Travolta exactly? Only some of the lyrics seemed to.

Spruance described their writing process, including writing “Travolta”:

“‘Travolta,’” Spruance said, “another collaborative composition, started life as a series/chain of riffs I wrote in college called ‘A Walk Through Necropolis,’ which had been scored and part-written for the university jazz band but to me never had a satisfying bridge section. Later on Patton had written a riff that contrasted perfectly if inserted into this piece, and it was 100 times better and more inspired than any of my own hitherto uninspired solutions. With that addition, and the magic glue of the atonal ‘come-down’ section (‘Grease is the Word’ etc) which came from a collective improv, the ‘snake’ was complete. By myself, in the context of an independent study college composition class, I’d trapped myself in a morbid snafu with some promising but dead riffs—but looking back, maybe those were always destined to be resurrected in a Mr. Bungle song.

This is the appropriate metaphor, because we always referred to our unfinished sketches as ‘graveyards’ of riffs. At first Patton and I especially compiled these endless mortuaries of ideas on cassette and would hand copies out to everyone in the band. It was almost like a cry for help. Later on, Bär caught that bug too. For sure, the collective song writing was always more like a resurrection of ‘parts’ stitched together, given life by a Frankenstein possession to make it all finally LIVE.

But other songs arrived with fully written chords and lyrics: Trevor’s ‘Slowly Growing Deaf’ and ‘Egg,’ Patton’s ‘My Ass Is on Fire’ and ‘Squeeze me Macaroni,’ with instrument voicings and other details being collaboratively worked out. Patton did the lyric writing on songs I wrote the music for, like ‘Carousel,’ and I think most of ‘Stubb [a Dub].’ Pretty sure those songs would be unbearable now otherwise.

Differently, Travolta’s lyric concept (which was very well redacted by Patton), came about in a very unique way. There was a spontaneous brainstorm by the whole band during a long night drive somewhere. For some reason we were obsessing on the hypothetical inner experience of a person who lacks almost all sensory input (deaf, blind, limbless and with mouth sewn shut). Everything he experiences is tunneled through a highly developed, almost miraculously compensatory sense of smell. He is thrown onto a trampoline—by who? a sick torturer laughing at him? loving parents attempting to provide something joyful that ‘normal’ kids do? How would it matter in either case? As you might expect from a bunch of alienated teenage delinquent heshers pondering over such questions, we were in collective hysterics over all of this. The truth, though, looking back is that we very much identified with this tragically monstrous character, who in his extreme sensory isolation was effectively living outside of time and space. I say this now, but 400 miles from anywhere, pre-internet, we were receiving our cultural referents in a way that could be compared to breathing through a tiny straw. And in some way, therefore, we were therefore free from their actual influence, free to imagine them any way we wanted to. We weren’t thinking this about ourselves at the time, but the Travolta figure exemplifies the idea that when left only with one’s imagination, and some vague other impressions from far off, such a suffocated entity might not feel deprived so much as take advantage of the elasticity of his state. To become something of a shapeshifter. In our adolescent gloom, therefore, ‘Travolta’ would of course take on the identities of various megalomaniacs; Hitler and Trump are mentioned, and there’s something prescient there about pathological narcissism mixing with the unbounded entrepreneurial spirit, peppered with a life mission of compensatory revenge.

Anyhow, somehow Patton managed to capture the mass evocation of this unfortunate/fortunate hallucinatory character in his lyric, and the song became ‘Travolta.’”

See? Travolta is one of the ultimate early Bungle songs.

Then again, so is “My Ass Is On Fire.” It’s built around a heavy metal riff, and the guitar alternates with eerie ice-skating rink plunges on the organ and bursts of horns.

In a break between verses, the music dissolves and Patton’s voice takes the lead. First you hear a quiet muttering in the background, like a madman whispering in your ear. “...Huh, wha?” He seems to be waking up. He’s confused. Then he directs his ire at you: “What’chu looking at, fuck? What’chu looking at, FUCK?” Here’s the proof, you think, he’s clinically insane. Why’s he yelling? Who’s looking at him? I can’t even see him. This is a CD. The hard consonant echos slightly: fuckkkk. He draws it out. Then the scene shifts. The rhythm changes, the guitar riff. In a higher register he howls: “Don’t. You. FUCKing look at me!” Different voices, with the accent in each sentence falling on different words, before a mess of voices come in to create a tangled mess that sounds nuts, but the way Patton puts emphasis on different words and parts of words, shows what a talented singer he is. And the babbling layers of voices here is the sonic equivalent of a horror movie, the sound inside a traumatized mind. It’s skillfully done, especially for 20-year-olds. Then the band falls back into one of the main riffs to get back to the music. It’s one of the weirdest interludes in rock ’n roll. I loved it as a teenager, and I loved how Patton could play so many characters on one album while still singing seriously with such soul and power when he wanted to, even if it’s on the Welcome Back Kotter theme.

Patton’s many characters include the psycho, the clown, the headbanger, the comedian, the thespian, the smooth jazz crooner. Maybe he contained all of those personalities at once.

After demanding that we don’t fucking look at him, he switches from the menacing violent character to the apologetic ejaculator. Over a killer guitar riff, he screams, “It’s beyond my control. It’s beyond my control. It’s beyond my control. I’m coming!” Every teenage boy can relate to that. But is that really what he’s singing about? Who knows. It doesn’t matter. The chorus sweeps you away: “It’s not funny my ass is on fire! Paraplegic inhuman liar.”

Where does stuff like that come from? Maybe he had a spicy burrito one day, and when he came out of the bathroom, his friends laughed and he said, “It’s not funny, my ass is on fire.” The magic is that stuff like this comes at all.

The nearly eight-minute song’s ending is just as brilliant as the rest. Patton sings the word ‘redundant’ over and over and over, in different voices, over the same chugging guitar riff and heaving monster voices, as the drummer hits things wildly and the song falls apart, degenerating into a cacophony of crashing sounds and growls.

That’s them having fun and being as annoying as possible.

“This is the first CD I was ever on,” said Dunn. “I was 23 and still lived at my parents’ house when we recorded it. That’s kind of embarrassing.”

But by the time they were recording, they’d played some of these songs so much—some for three years—that they were sick of them. “That might have something to do with why we started dumping samples of pinball machines and dialogue from Blue Velvet into the songs,” Dunn said.

They sampled videogames like Super Mario Bros, Smash TV, and RBI Baseball, and the pinball games Earthshaker and Cyclone. “Love Is a Fist” includes samples from the old school porno Sharon’s Sex Party. At the end of the line “I’m gonna pinch a ravioli on the Pillsbury dough boy” in “Squeeze Me Macaroni,” you can hear a sample of actor Angus Scrimm from the movie Phantasm.

“All the samples were recorded by Trey on a portable DAT recorder,” said Dunn, “the arcade games from Sharkey’s [Arcade in Eureka]; the screeching tires of Trey’s car (heard in ‘Stubb’); the quarters dropping into the porn booths at the Century Theater in SF. I recorded the train sequence and the domestic violence blurb (just before Love is a Fist) on my Sony cassette recorder with a condenser mic. Yep, those were the days of our lives...”

They even recorded audio of themselves jumping a train and included it at the end of the song “Egg.”

The friends they’d made in San Francisco also added layers of sound to the songs.

“Our friend and fellow Eurkean Rob Green was hanging around and became obsessed with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet so it was ALWAYS on in the lounge at the studio,” Dunn wrote. “We subsequently befriended a couple of strippers who would hang out in the recording studio and say lewd things into the microphones for us. We really got a kick out of that. We were also friends with a band called The Deli Creeps whose guitar player went by the name of Buckethead. The singer, Maximum Bob, was a big guy who used to light his farts with matches. You can hear him chanting ‘over and over’ at the end of ‘My Ass Is On Fire.’ So, yeah, there were some weirdos hanging around.”

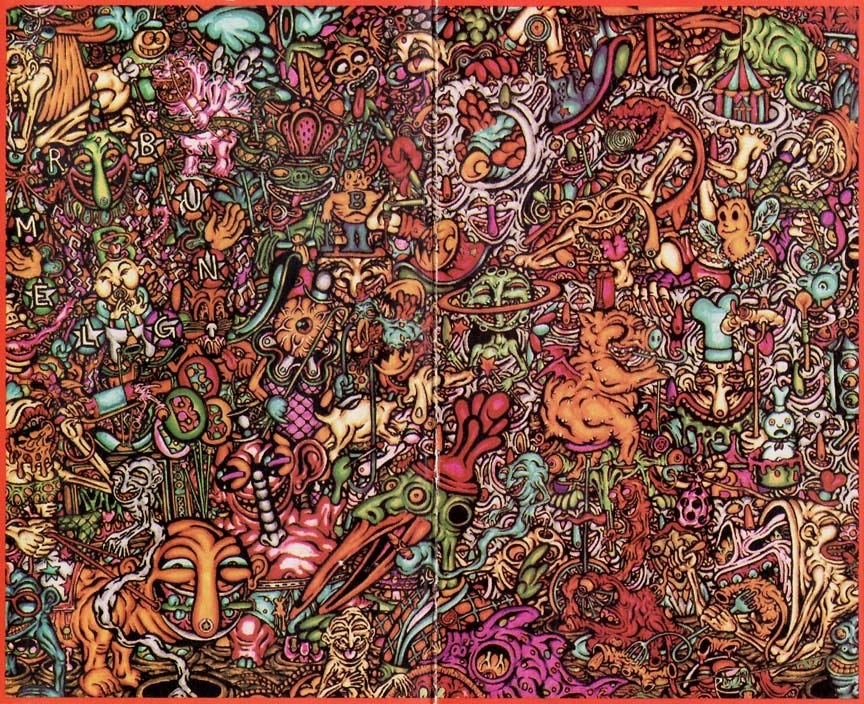

On August 13, 1991, Warner Brothers released Mr. Bungle. There has never been anything like it. Still a cult classic, it’s one of the strongest debuts in American underground music, and one of the weirdest. The record’s imagery and lyrics are filled with what Spruance called “a tornado of sociopathic escapism and scatological ultraviolence.” That aesthetic became the band’s brand, one that they worked hard to shake as they grew up and their music evolved in the following years.

“Though I look back on some of this music with horror I think it really represented us in our youthful, small-town escapism,” Dunn wrote of the album. “All we had to think about in those days was music, sex, food, quadriplegics, the circus, dogs and auto-asphyxiation. A glimpse of Eureka through the eyes of kids who had to get out.”

These educated rural California weirdoes made a masterpiece from that childish mess of impulses, which is why it still speaks to the weird post-teen period in many young peoples’ lives.

It certainly did mine in the early ’90s.

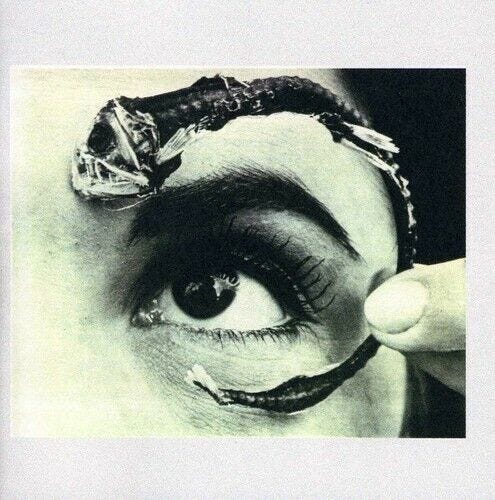

A pudgy clown face greets you on the album cover. He’s up to something—you can’t tell what. Arsen? Murder? Turns out the image comes from the story “A Cotton Candy Autopsy.” It’s the first issue of the DC comic book series called Beautiful Stories for Ugly Children, written by Dave Louapre and illustrated by Dan Sweetman, from 1989. This clown’s face is the first in what will be an endless series of what the fuck moments for listeners.

From the first terrifying notes of “Travolta,” I was entranced. This music was so dark and propulsive that Patton could’ve been singing about anything. The pounding rhythm pulled you inside and left you thinking: More, please.

All ten songs went that way: music matched with bizarre, inventive wordsmithing atop a symphony of audio clips of Patton straining on the toilet, soundbites, field recordings, and, I think, a Vietnamese language learning tape.

Lots of my friends’ extended friend group thought Mr. Bungle was too weird to listen to. Sure, it was interesting, but the music? Unlistenable, they said. I could understand that. It jarred the nervous system. That’s partly what I liked about it, and how it always surprised you. My adolescent sense of humor also matched the album’s poop jokes, porn jokes, and Satan references. I played that Mr. Bungle CD constantly in my Pontiac LeMans.

The thing about the early ’90s is that there were so many different types of bands, and as an alternative kid, you could like them all. You didn’t just have to be goth or punk or rock ’n roll the way people tried to make you in the early 1980s. You could like this weird circus music, and Beck, The Cure, De La Soul, and Mazzy Star, and still love some GN’R. You’d get shit for liking headbanger music, but you could still get away with it.

As miraculous as it was that any major label signed Bungle, it was just as wondrous how Warner Brothers chose to promote them.

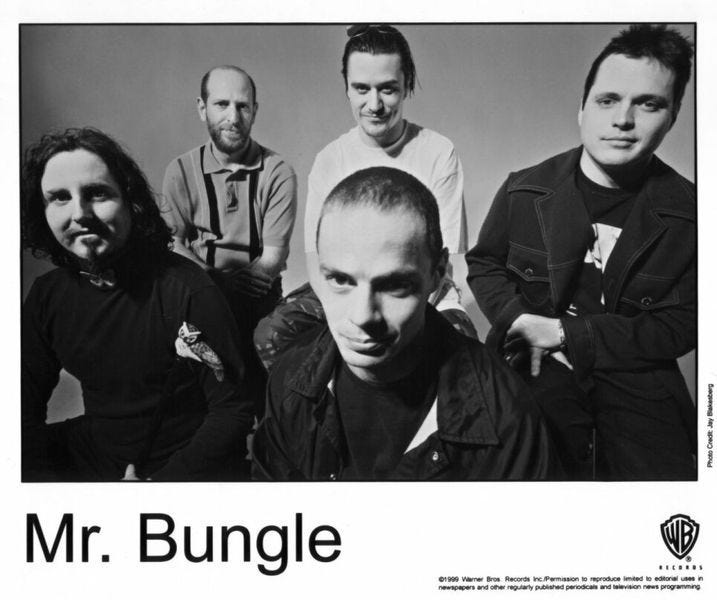

Some record stores gave customers a free bottle of Mr. Bungle bubble bath when they bought the record. Along with a glossy band photo, Warner Brothers sent radio stations and record stores written publicity material where the label’s business folks struggle to describe the band and its appeal: “Featuring such apocalyptic anthems as ‘Slowly Growing Deaf,’ ‘Love Is A Fist,’ ‘The Girls Of Porn’ and the terrifyingly original ‘Quote Unquote,’ Mr. Bungle by Mr. Bungle makes hamburger out of every cherished cow within rifle range...and cooks up something compelling, totally committed music in the process.”

Music “this weird deserves an air of mystery,” one reviewer said of the press photo. And this album, it said, “is a brash, unpredictable punk-carnival-jazz-cabaret-horror mix in which melodies, instruments and time signatures play wild games of chutes and ladders while sound bites and obscure samples scurry underfoot.”

Before the internet, that press photo was about all you could find about the musicians. Their identities were a black hole, and in that vacuum, they played a wise game: create a whole entertaining universe while concealing the truth.

They weren’t the first band to wear masks. Since the 1970s, The Residents had done this, too, wearing giant eyeball helmets and other costumes to preserve their anonymity and keep the focus on the music, but Bungle took the idea to the Alternative Era.

Besides having fun, the masks helped them try to avoid promoters capitalizing on Patton’s role in the more visible Faith No More and trying to sell Bungle as Patton’s other band—like, Look, come see the singer of Faith No More in Mr. Bungle! So on this album, Patton went by the name Vlad Drac, and for fun, Spruance went by Scummy.

“We wanted to be our own thing,” said Dunn. “We were never ‘Mike Patton’s other band’ and aside from sharing a singer we had nothing to do with them. We were a collective that Mike was a part of from the beginning.”

Everything about them was mysterious, but the music was more than weird. The songs themselves were well constructed and musicians talented. Mr. Bungle is one of those albums that delivers something new with each listening: whole universes of sound beneath the lyrics and instruments. Back when you’re a teen, you would actually put on headphones and lay on your bedroom floor listening to music, and you would always hear new things. Mr. Bungle was a well whose bottom you couldn’t reach. While my friends and I drove around Phoenix on weekend nights, smoking weed and looking for parties, we’d also blast this album so loud that our car speakers tore and made our nights feel wilder.

The album’s initial pressing lists the first song as “Travolta,” but Warner Bros. had the band change the title to avoid legal action from actor John Travolta.

“Interestingly, Travolta, as a Scientologist, struck fear into the hearts of the Warner Brothers legal department,” Spruance explained, “so after the initial pressing of 20,000 CDs, we were summoned to the legal office and told that the song had to be renamed. Hence, ‘Quote Unquote.’”

The new title alludes to the missing name. Quote Unquote is also the title of an unauthorized John Travolta biography, so the reference is still in there, for those in the know.

The band made a music video for it, but MTV wouldn’t air it because if featured bodies dangling from meat hooks, disturbing gimp mask closeups, and a creepy clown wielding a kitchen knife. Radio stations didn’t play the album, either. It was just too weird. It still sold well despite these mainstream channels’ cold shoulder. Bungle didn’t care. Their wild live shows would continue creating buzz word of mouth, which is the best way.

They recorded three other songs for Warner Brothers but kept them off the album: The old originals “Mr. Nice Guy” and “Platypus,” and a Tom Jones cover called “Thunderball,” from the James Bond film. They put “Platypus” on their second album. The others remained outtakes.

Twenty-five years after recording the song “Dead Goon,” Spruance was still proud of it. “I think the end of ‘Dead Goon’ holds up really well,” he said. “The scene where the stereo auto-panner has the dying kid (vocals and creaking rope) swinging one way and the whole world (the band/music) swinging the other. I realized awhile back that it’s a perspective trick not unlike Wozzeck’s death in Berg’s Opera, where the sound of rising instruments is in relation to Wozzeck’s perspective going down, sinking and drowning. In ‘Dead Goon’ there’s an ecstatic (out of body) sense in that whole section that really worked. Partially, I think, because after a whole album of over-determined indulgences of male musical angst, the arrangement becomes indeterminate and free as eros and thanatos finally collide in an aleatoric suspension. If nothing else, it’s got to be the most lucid depiction of autoerotic asphyxiation ever attempted, and what a fitting end to such a ‘libido charged’ record.”

Dunn got asked about the infamously difficult “Dead Goon” bassline so much he posted a transcript of it, with instructions, on his website. “Good luck,” he wrote, “and let us never speak of this bass-line again.”

Mr. Bungle was the perfect album for that time: adolescent, scatological, cartoonish, filled with curse words, yet musically advanced and stylistically sophisticated, and its warped sensibility appealed to the increasingly warped state of mind that weed, keg parties, and psychedelics put my friend group in, never mind how the album’s sense of wanton abandon appealed to our own feral approaches to life.

In hindsight, I wish my friends and I had poured ourselves into making music or something the way the Bungle boys did. Instead, we had fun and made memories and relegated ourselves to fans.

Naturally, as a young listener, I also assumed the band was on drugs. What kind of mind created music like this? In 1992, my best friends and I spent our weekends getting trashed at parties. We assumed a band as weird as Bungle got trashed up, too. Hard drugs were rampant in the early 1990s and would kill many well-known musicians. Everything about Bungle seemed too warped to be sober. We were too young to realize that theirs was pure originality and creativity.

My assumption was not simply we imposing my own party lifestyle on every wild artist I saw. It was that many teens and early 20-somethings like me actually don’t understand how creativity works. You’re naïve at that age. You think creativity comes easily, that it’s about “altering your conscious” to see the world in a new way. You fail to recognize how much hard work and clarity goes into a creative life, that art involves discipline and practice, and that routine inebriation can’t provide the material that artists build their lives around. It’s so easy to confuse creativity with intoxication. Turns out, Bungle was not drug music. Sure, this music was fun to listen to while on drugs, but it wasn’t the kind you made on them. You certainly don’t play this highly technical music intoxicated. Playing it required proficiency. The fact that these musicians weren’t drug users made them a thousand times cooler and weirder to me.

Being drug-free in the 1990s was one of the most punk things you could do. Patton is famously sober. He drank energy drinks and coffee before shows. These Bungle guys didn’t even seem to smoke cigarettes, and like their musical itself, they were very un-90s. This was a lesson I took years to recognize, but once I did, it shaped my whole life. Back in high school, I’d get stoned and try to draw things like Bungle’s CD insert, and it never came out as well.

At Bay Area shows in 1991, the band played covers songs by Mariah Carey, Queen, Elton John, Belle Biv DeVoe, Mötley Crüe, Journey, and Tom “T-Bone” Stankus, and they dialed in their performances of Mr. Bungle.

Their profile was growing, and they were ready to leave the North Coast.

After WB signed them, the horn players still lived in Eureka. As Dunn told the crowd at The Omni in Oakland in 1991, after “My Ass Is On Fire”: “Hey, check this out, man. K. The two guys that play sax in this band, you know, their name’s Bär and Theo, well, they’re going to school up north, and they got classes tomorrow at nine in the morning—yeah, it’s pretty cool. I get to drive back after the show, and I’m pretty stoked about that, and I’d just like to share that with you.” Then they rip into “Platypus.”

“By 1992 Danny was living in San Francisco,” Dunn recounted on his website, “and I remember crashing on his couch in the Haight the whole time we were recording. What a drag. Trey had his car and we’d have to drive around looking for parking all night. Then we'd set up plastic army men on the mantle of Danny’s living room and shoot them off with rubber-band guns. I also remember eating a lot of burritos and Thai food. Our friend and fellow Eurkean Rob Green was hanging around and became obsessed with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet so it was ALWAYS on in the lounge at the studio.”

Later that year, Dunn finally moved to San Francisco, too, and two months later, the band hit the road on their first U.S. They were all in their early 20s.

When other members moved from Arcata and Eureka to SF, they earned money playing in bands and elsewhere. They had to hustle to survive and still create Bungle music. Spruance remembered:

“When Patton was around, we never consciously rushed to get things going. It’d happen more naturally than that. He’d come home and there was always catching up to do. Show n’ tell. Mutual inspirations. Eventually we’d start piecing things together... spontaneously freak out on organs and record the good parts. Trade those graveyard cassette tapes of ideas and ponder on each other’s riffs for the months we never or rarely saw each other (meaning all of us). Nothing was ever on hold.

I can paint the picture better for you. All the rest of us had very active lives in music in San Francisco in the early ’90s. Danny was in a really popular local band called Dieselhed. Trevor, once he moved down from Eureka, had real gigs with real musicians almost every night. I rarely ever saw him. Bär was holding down multiple jobs. For myself, I was immersed in a scene of I guess ‘post-punk’ something-or-other that was pretty vital at the time. Gregg Turkington came out of this scene. Caroliner Rainbow. Thinking Fellers Union Local 6. Three Day Stubble. I made some good friends in that world & once I finally stopped fucking around living in my car, I went pretty full on into honing my recording/production skills. Got happily lost in a billion odd projects, with many very brilliant not-so-known people, many of whom are too shy or too unimpressed with their own creative output to assert themselves very much.

So to me (and the rest of the band I’m sure), Mr. Bungle in the early ’90s was like an orbiting satellite that we the band members all had in common. It benefited from each of our separate musical forays.”

In ’91 and ’92, Bungle wasn’t a satellite for. It was my center.

I went to an all-boys Jesuit high school. I had long hair and earrings and wore band tees under my regulation collared shirts. I pull into school each morning blasting my music. Since it was Arizona, I often had my car windows down, so the sound escaped with the cigarette smoke: Alice In Chains’ “We Die Young,” Nirvana’s “Dive,” Smashing Pumpkins “Tristessa.” Bungle definitely took a few ticks off my long-term hearing. “Travolta” and “My Ass Is One Fire” had the most devilish riffs.

When I played Bungle for some my classmates, though, many looked at me and said, “You’re into some weird shit, man.”

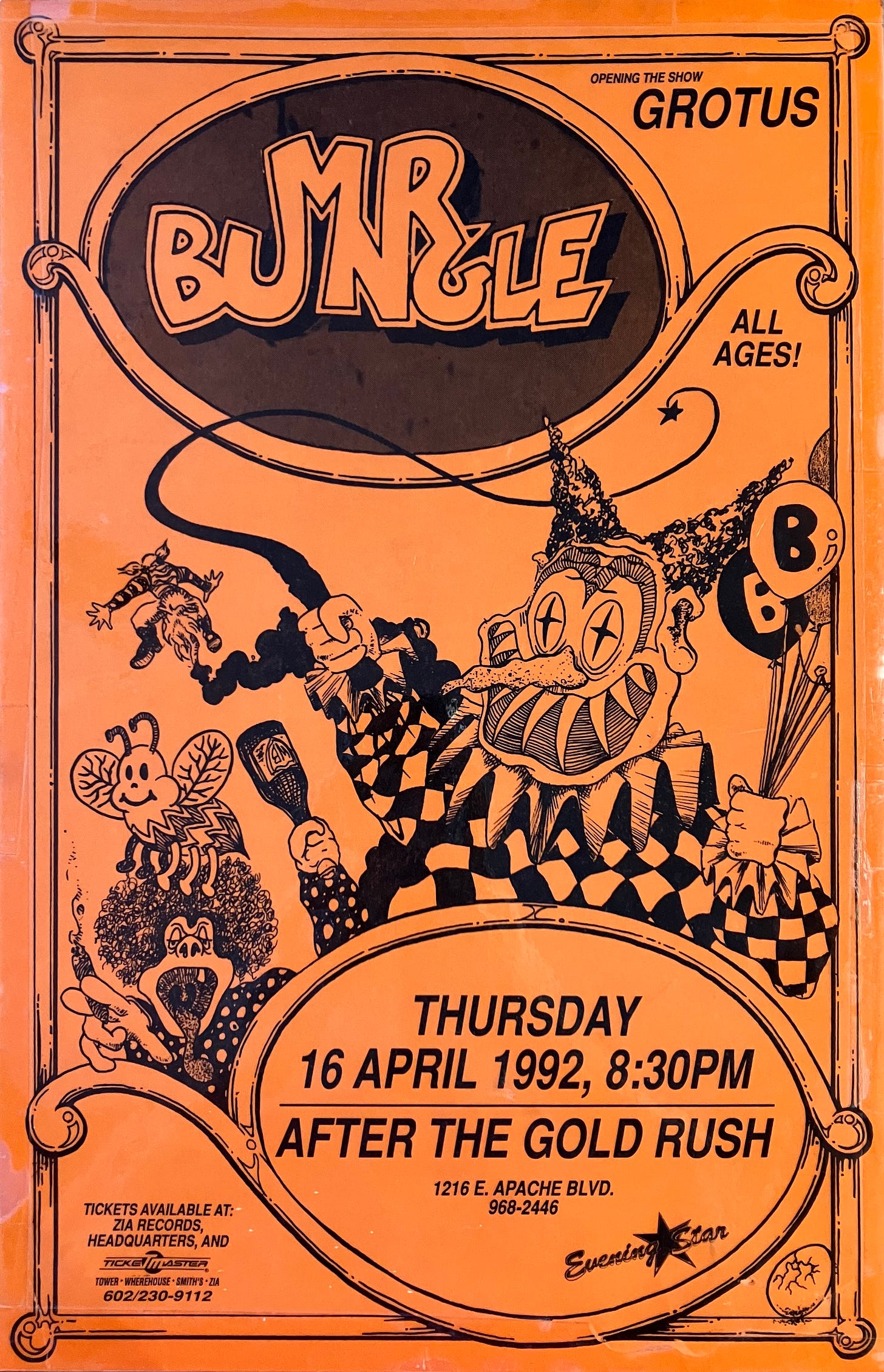

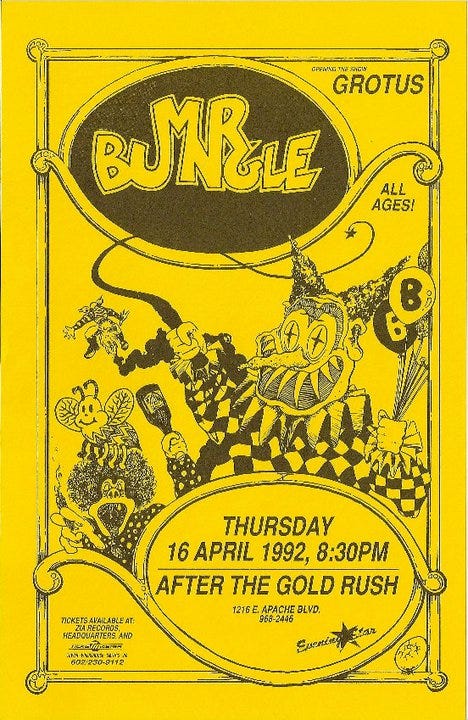

On April 16, 1992, 21 days after someone recorded Mr. Bungle playing “The Stroke” in Chicago, they played a club called After The Gold Rush in Tempe, Arizona. I lived nearby and would later attend college down the street. My friends and I had noticed the concert poster hanging in the window of a nearby head shop.

Decked in our Fresh Jive t-shirts and sagging jean cutoffs, my crew went to this head shop all the time to buy screens for our pipes and rolling papers for joints, and buy concert tickets, so we got to know the manager, Ted. Tall and soft spoken, Ted had thick brown hair that hung down the front of his tie dye shirts. His long hair was way cooler than mine, which could only go as far as my shoulders according to my Jesuit school’s dress code. Ted also didn’t have all the split ends I did, and he was actually old enough to buy beer. My friends and I still had to fish from strangers outside convenience stores.

This was not only way before you could legally buy weed in a store. This was back when you couldn’t talk about weed in a head shop. You spoke in code, referring to bongs as “tobacco water pipes.” Any repeated allusions to illicit substances got you kicked out quick—never mind that the small glass pipes with the rounded ends were only used for smoking speed or cocaine. Yes officer, we often joked, we come here weekly because we love tobacco enough to buy a four-foot bong so smoke it.

On the day we spotted the Bungle poster, I asked Ted if I could have the poster after the show. Sure, he said, and penciled my name on the back of it. “Just pick it up soon after so it won’t get lost,” he said. That was generous. He was impressed that my teenage friends and I liked Bungle. We loved Bungle, I told him. In fact, if he could keep a secret, I planned to bootleg the show myself. I’d just recorded Nirvana playing with Pearl Jam at the big auditorium down the street. My recording sounded like shit, but I still had to try bootlegging Bungle. Ted asked about my equipment. It was a regular old handheld Panasonic cassette recorder, I said, but I recently upgraded by buying an external stereo microphone from Radio Shack. He must have known that any recording made on that setup would also sound like shit, especially a loud band with horns and distorted guitars, because he then did something more generous than I ever expected of an elder stoner: offered to smuggle in the tape recorder for me.

“Really?’ I said. “You wouldn’t mind doing that?”

“Not at all,” he said.

Ted explained that he knew the band somehow, and he described their past shows: how they’d brought full-size dummies on stage to tear into piece and throw into the audience once. Since they were going to put him on the guest list, he would bypass security and smuggle in my equipment without a hitch. That would spare me the bootlegger’s biggest hurdle: entry. I knew from experience that if security caught me smuggling in a tape recorder, they might not let me into the show. That would be my worst nightmare, way worse than having my equipment confiscated. The whole reason I wanted to tape the show was so I could relive it over and over for the rest of my life and give my children something to inherit one day besides my old Powell Peralta skateboard and the stories of killer rock shows I would tell them about to the point of irritation. I had to see it.

Ted nodded his slow Deadhead nod and tucked his hair behind his ears. All I had to do was bring him the equipment before the show.

In fact, Ted said, the band had filmed one of their shows at a small Los Angeles club, called Club Lingerie, so they could impress Warner Brothers. It was a soundboard recording shot on multiple cameras. He promised to try to get me a copy of it. He had it on VHS. On the way out, I grabbed a huge stack of small yellow concert flyers and left the store feeling higher than I ever did under the influence of the dirt weed we smoked through this head shop’s pipes. For one of the first times in my life, I felt cool enough to think I was truly on the inside. I was a stoner and a slacker and couldn’t get a date, but now I had prospects. I was a bootlegger at last: in love with the energy of live recordings, obsessed with creating a record of these passing musical moments, and having a souvenir of our fun nights out. Now I would create a Bungle bootleg. Sure as shit no one else in our friend group could say they’d done that.

I went back to the headshop a few times before the show, once to give Ted my equipment, the rest of the time just to talk to him about music. During one visit, the Bungle drummer, Danny Heifetz, called to talk to Ted about when they were coming to town. When he told me who it was, I stood there in awe, thinking This guy is so cool.

We agreed to meet inside the club so he could give me my tape recorder and mic.

The night of the show, my friends and I waited outside the club in the cool spring air. After the Gold Rush held 700 people. As fans trickled through security, people crowded around the entrance smoking cigarettes and waiting for friends.