Sublime Played Their Most Powerful Song at Their Last Show

“The Ballad of Johnny Butt” is one of the California band’s most moving songs, even if it’s the least-serious sounding

“Lovin’ is what I got. Said remember that.” —Bradley Nowell

For a perpetually stoned band that took very little seriously, the California band Sublime played some seriously powerful music.

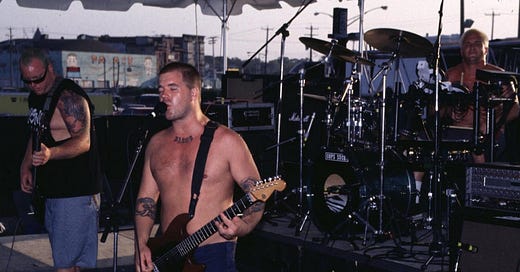

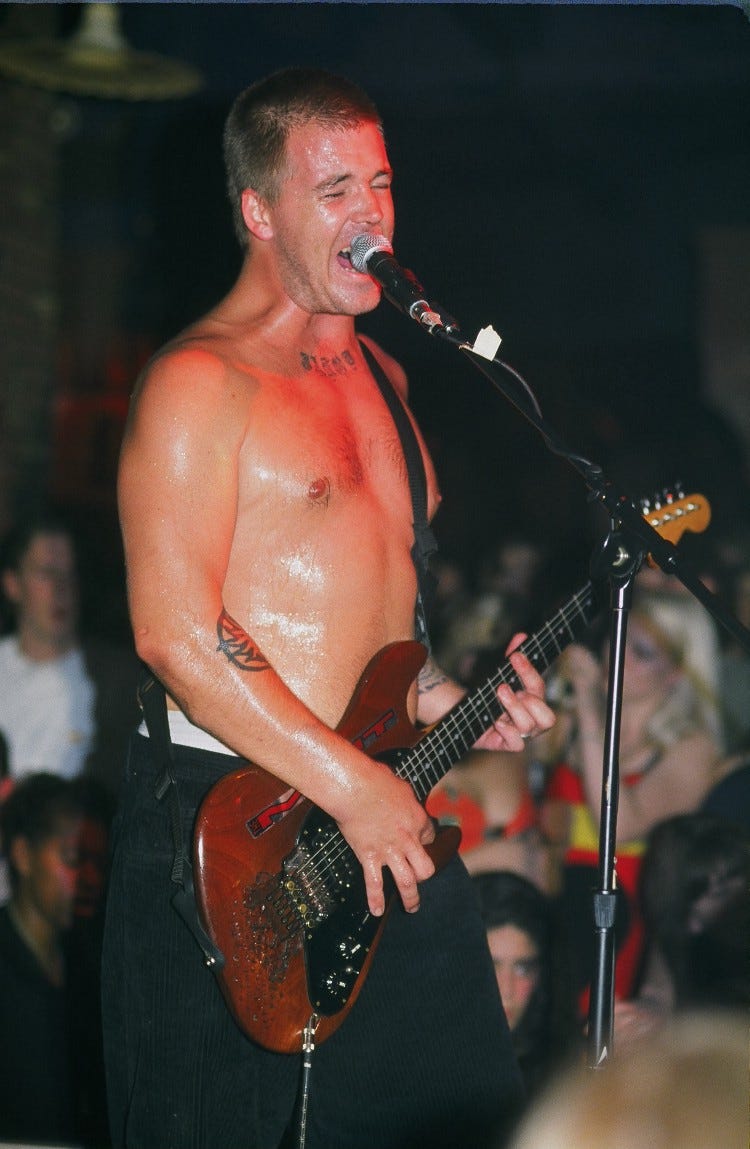

Twenty-plus years after their dissolution, you might not think it’s cool to like Sublime. You might think of them as a white boy reggae-punk “SoCal” band for backwards hat frat boys who smoke herb but hate peace and ride longboards to their college classes even though they live in Ohio. And in many ways, that’s what Sublime represents to some people. But Sublime’s music still means a lot to many people. It’s the soundtrack to their lives. It’s the sound of southern California in the ’90s that still sounds like southern California today. It’s the sound of freedom, rebellion, youthful good times, of sobriety for some and permanent summer for others. Twenty years on, you can still hear fierce originality in many songs and surprising depth in others. Because trust me when I say that underneath Sublime’s cool, tattooed beach dude image—always holding beers, rarely wearing shirts—and beneath the proud Long Beach, low-rider, cholo-style regionalism—was some incredibly tender, emotionally charged music, some of it built from the same improvisational abilities as jazz, except drunker. Not the fast songs that spun the moshpit, like “New Thrash” and “Seed,” which are awesome. Not the irie, upbeat, joyous jams like “Foolish Fool,” “Doin’ Time,” and the reggae cover“ Kingstep,” which are timeless, too. I mean the pained, heartfelt songs like “Badfish,” “Pool Shark,” “Jailhouse,” and “Pawn Shop.” Sublime’s music mixed reggae, dub, punk rock, surf rock, hip-hop, acoustic porch jams, even Blues. It was diverse, and within that range of styles you find songs that inhabit the more sensitive side of the musical spectrum, especially their final live performance of “The Ballad of Johnny Butt.” A fan recorded them playing it the night before singer Bradley Nowell died of a heroin overdose in his motel room at age 28, in the bed next to his drummer Bud Gaugh. To me, few songs capture Sublime’s maturing talents and wounded beauty as this final live version, and few songs embody the band’s contradictory essence more clearly: dudes playing cheery party music while courting death by the beach.

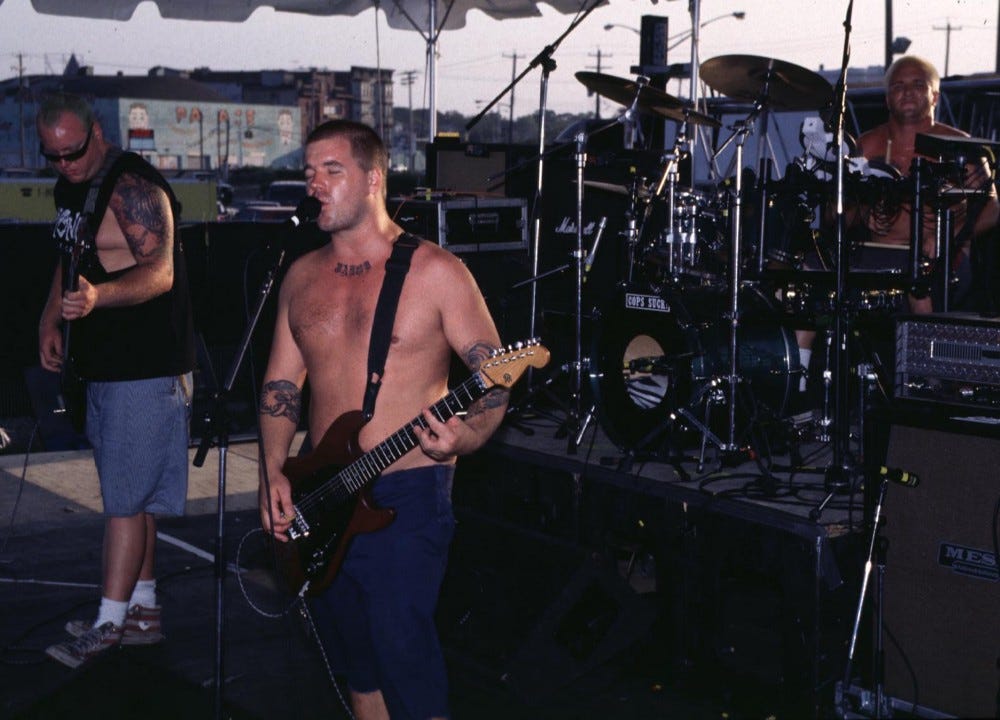

Despite being in his twenties, Nowell was a powerful vocalist with tons of feeling and an astounding range. He had sweetness and gravel in his voice. He could freestyle over anything, adlibbing beautiful melodies over short passages, on camera, or in front of an audience, or with only a few minutes of expensive studio time to deliver. He sang about a lot of stupid adolescent shit involving punani, weed, guns, his dick, his asshole, planting his seed, and 40ounces to freedom, lyrics which haven’t aged well to those of us who have grown more sensitive and empathetic with age. But he also sang against date rape. He sang about loving his dog. He sang about spreading the love he’d found in his music and in his friends. He urged listeners to “start uniting,” “be the best you can be,” and “stay positive.” He urged people to embrace our short, unpredictable lives because “you might get run over or you might get shot,” and he sang about having soul, which he had in spades. You can hear it. Soul is especially palpable in Sublime’s last performance of “The Ballad of Johnny Butt.”

The original trio played their last show on May 24, 1996 at the Phoenix Theater in Petaluma, California, north of San Francisco. It’s a sloppy performance. A concert promoter named Lil’ Mike, who’d professionally recorded previous Sublime performances, encouraged his girlfriend “Badfish” to record the show, so she sat up in the balcony and taped what she could on her handheld Sony Walkman. Her cassette captures a band that isn’t as enthusiastic, tight, or fun as they were at their best. Sometimes they’re on fire. Sometimes they sound tired. They go through the motions on some old favorites. Bradley forgets lyrics to new songs they’d recorded a few months earlier for their major label debut. He often forgot lyrics, and he just as often made them up. Improvisation was part of Sublime’s charm. But something about the band was off. Maybe the crack they’d smoked that morning in Chico set a dark pall over the whole day. Maybe death has a way of darkening a room before it leads you away.

It’s odd, because Bradley called his wife Troy Dendekker after the show, raving about their performance. “It was the happiest I had ever heard him,” she remembered on a VH1 special. Jason Boggs, singer and saxophonist of the opening band Filibuster, agreed. “Sublime killed it that night. They did a great, great job. Considering how much we’d all been partying before the show, I was very, very impressed at how tight they sounded.” Other listeners had a different impression.

“I recall feeling sheer disappointment,” said a fan named Sara Sugrue. “I thought it sounded awful, especially Brad. I feel a little bad saying it, being that he’s passed.”

Tom Gaffey, who managed the Phoenix Theater agreed. “I don’t want to go against what common belief is, but I do recall that I was kind of bored with that show. I’m sorry to say that. It just didn’t have the energy the other shows had had.” Thanks to Badfish’s recording, fans can decide for themselves.

Sublime professionally recorded a number of their shows on analog tape and DAT through the mixing board, getting crystal clear audio through multiple tracks, and later officially released some of these concert recordings. The band also allowed fans to record their shows, as long as tapers provided a copy for their archives. Bootlegging was a sizeable pirate economy in the 1990s, and Sublime’s policy was an innovative, punk rock approach to combating it, and also a way of giving fans what they wanted: a souvenir of their experience. In the process, the band got a free video and audio library, documenting their evolution without investing additional time or equipment. This aligned with their DIY approach to everything, from recording for free in their friend Miguel’s college studio in 1990 and 1991, sleeping on peoples’ floors on tour, self-promoting by printing their own flyers and distributing their own homemade cassette tapes. Their success was largely grassroots. Listening to Badfish’s audio recording from Petaluma, I hear a mediocre show—not their drunken worst, but far from their tightest best, like the 1994 show Lil’ Mike recorded at San Francisco’s Klub Kommotion—but there were some serious highlights, especially “The Ballad of Johnny Butt.” Combined with the song’s gravity, this version’s dark tone contrasts so profoundly with the bulk of the band’s reggae-based music that it stands out as an oddity in their oeuvre, even if listeners can’t identify why. To call it a serious song would miss its power. It contains Nowell’s entire struggle in five lines:

So, Johnny just keep pushin’ ’cause the streets are yours

There’s come a day when all that shit won’t matter

So, shoot it up, shoot it up

It just don’t matter

When you’re resisting anyway

Although “The Ballad of Johnny Butt” is a cover of a song by the obscure Long Beach punk band Secret Hate, the lyrics that Nowell added lift the song from an obscurity to a classic, transforming a fun but forgettable tale of teenage rebellion into a sophisticated anthem about addiction. Nowell sings from the miserable space between temptation and defiance, endurance and defeat. Knowing what happened to him the next morning makes this final version even more poignant, but the song’s power lies not simply in his fate or in the lyrics. It lies in Nowell’s delivery—how he sings those lyrics—and his guitar work.

“The Ballad of Johnny Butt” encapsulates everything Sublime was during their brief reign. Frequently intoxicated yet clear about their artistic vision, they were confident musicians spiraling in and out of control. They were vulnerability and bravado; love and anger; laughter and tears; carefree and burdened; the high and the hangover; a keg at a funeral; mischief and disease. This song is evidence of how young men can conceal great hurt beneath scatological humor, or rise above the joke. This song, like many of the songs Sublime covered or incorporated into their own material, became a Sublime song as much as their original compositions, because they imprinted it with their unique musical style. As a cover, it’s also a searing example of the way the best borrowed music no longer belongs to its songwriters, and proof of the artistry required to make other musicians’ material your own, in the great reggae, hip-hop, and Blues traditions. In reggae, countless people recycled other peoples’ music, from drum beats to basslines, even lyrics. The free exchange of ideas is integral to the genre—which makes it almost open source. Sublime went further than recycling. A true American, multicultural mutt, they built entirely original, modern-sounding songs from different genres, glued together by hip-hop and reggae, alluding to the past while documenting their present in a way that charted music’s multicultural future. The haunting way Bradley played “Johnny Butt” that final night almost seemed to unconsciously channel the unavoidable fact of his impending doom, standing like a bridge between this world and the next. The bootleg doesn’t sound great, but it’s clear enough to feel the life that Nowell put into it.

You wouldn’t expect that from such stoned beach rats, but letting peoples’ looks determine your expectations is always an egregious error. Just like you wouldn’t expect such depth from a song with such a juvenile name, but my ears don’t lie: That last version of “Johnny Butt” offers a rare moment when a tatted up, 1990s-era southern California beach dude tears open his macho exterior to make himself vulnerable. This version drips with pathos, longing, and fatigue. It’s tempting to conclude from his lyrics that he knew he was going to die, that he expected it. But anyone who uses needles knows death is close. They just don’t know how close. In this song, Nowell is not simply confronting death or exposing himself on stage. He’s enacting his inner life up there, working through his troubles in front of a room full of strangers who idolize and deify him and think he’s cool as shit. And he was cool as shit. Look at him: the textbook 90s beach god, living the coastal dream, free from a desk job, able to surf, enviably uninhibited in the way true punks are by having no concern for what you think, even though things inside, in his words, “weren’t so cool to me.” Instead of boasting about surviving addiction or celebrating his subversive behavior with some lyrical middle finger, he’s singing his shame, singing his self-loathing, singing his truth beyond his badass reputation. Nowell transformed “Johnny Butt” from a passing butt joke into a proxy for himself—and for all of us who have struggled with addiction—for being a butthead, a dumbass, a fool foolishly doing what he knows he shouldn’t be doing—and hating himself for it. That makes this song an existential quandary by a person who’s had the fight knocked out of him, a young man worn down by years of indulgence, remorse, missteps, and struggle. Like Johnny, Bradley just keeps pushing on, as he sings, even though he’s barely alive, because as the chorus says, “we’s gots to overcome.” This is the sound of a person laying himself bare before he lays down forever. It’s pure and it’s captivating, and its humanity gives me chills. Because despite everything else Bradley Nowell was, he was also a deeply sensitive person. You hear it in Sublime’s original songs, and in the covers they chose. Never mind the stoned college fans in Billabong tees who hang Sublime posters next to Bob Marley posters in their fraternity houses. The broey reputation they give the band has nothing to do with why Sublime played the music they played.

Sublime made listeners feel good, and their recklessness turned them into one of the most tragic stories in modern rock history. Nowell, the original, charming, irreplaceable front-man, died two months before the release of the major label album that catapulted the band to international fame. Imagine: As his body rested in Westminster Memorial Park, his band achieved a level of success he could never enjoy or imagine. Two months after Nowell’s death, drummer Bud Gaugh told the Los Angeles Times, “Sublime died when Brad did.” But their self-titled album gave Sublime a life of its own, turning them into the biggest band of 1997, winning them an MTV video music award for a video that could only include archival footage of Bradley, an album that sold millions of copies and generated four hit singles which played all over the radio and MTV, in clothing stores and open car windows for the rest of the 1990s, to the point that Nowell’s friends and family had difficulty mourning, since they still heard his voice everywhere they went.

A lot went into that powerful song at Sublime’s mediocre final performance. By the time their never-ending tour arrived in Petaluma in May 1996, they’d been playing up and down the West Coast for nearly ten years, and Nowell was trying to stay away from heroin.

Sublime started in 1988 in Long Beach off Ocean Boulevard, at the house where Bradley’s father Jim still lives. Bassist Eric Wilson and drummer Bud Gaugh lived across the alley from each other nearby, in Long Beach’s Belmont Shore neighborhood. Eric and Bud hit it off. They formed a few garage bands, including the Juice Bros. They both got kicked out of high school for what was likely drug possession, though they refuse to say so. Eric had also been jamming with a neighborhood guitarist named Bradley, who lived down Ocean Boulevard in the upscale Peninsula neighborhood. Bradley’s parents had divorced when he was 10. His mother deemed him too much trouble to handle, so she sent him to live with his dad, a rock steady, practical-minded, soft-spoken contractor who lived on the beach, wore Hawaiian shirts, and played guitar. When Jim Nowell took his 11-year-old son sailing to the Virgin Islands, Bradley heard the Island music that would define his life.

Wilson was a quiet guy. Gaugh was rowdy. Nowell was both sensitive and vocal, so he sang in their short-lived bands. “When I met Brad, he was trying out for this junior-high-school band, and the highlight of their career was this talent show,” Wilson remembered. “He tried out for them, and they didn’t want him because they said he wasn’t good enough.” Eric and Bud had lots of time on their hands. When Bud got out of jail for some kind of mischief in 1988, Eric introduced Brad to Bud during Brad’s college spring break, and the three jammed for a week at Nowell’s dad’s house, wrote three new songs (“Romeo,” “Roots of Creation,” and “New Realization”), and recorded two old tunes of Nowell’s: “Date Rape” and “Ebin.” To start booking shows, they put those demos, their band name Sublime, and Bradley’s phone number on what became known as the Zapeda Tape. “It just clicked,” Wilson said, “just like that.” They were friends for life.

Sublime started as a party band, literally playing house parties in Long Beach backyards, and they took that circus energy with them everywhere they went. Their tour van was a party. Backstage green rooms were parties. Recording sessions were parties. Even group interviews descended into a chaos of jokes and banter and people drunkenly talking over each other while Nowell struggled to answer the interviewer’s questions thoughtfully. Before shows, they’d skate and drink and smoke cigs with fans, and wander the venues hanging out before taking the stage. Of course, the shows themselves were ragers.

Their July 4, 1988 show set the tone for their professional lives. Barely months old, they played on the beach in front of Nowell’s house. The concert devolved in what the OC Weekly called “a rowdy good time into a full-fledged riot.” “Brad liked riots,” his stepsister Katie Gibson remembered. “When they played that show, kids were totally destroying property, and the cops had to come in and shut the band down, clear the streets and kick everybody off the Peninsula.” Sublime “caused chaos wherever they went,” she says. “It was awesome.”

To Blaine Kaplan, who later became Sublime’s booking agent and co-manager, their December 1994 Klub Kommotion show epitomized Sublime’s appeal. “That was my first real experience going to some dirtbag, punk rock underground show, paying two bucks and walking in with a 12-pack. …There must’ve been about 25 friends on stage with them while they were playing. They’ve got this one friend, Buddy, who was part of the Church of Rock N Roll in the East Bay, and he was actually passed out on stage. Brad was straddling him while he was playing, and everyone was yelling, ‘Buddy, get up, you #@$^, and do 20 push-ups!’ He started waking up, and when he came to he grabbed the mic and said, ‘There’s no need for push-ups.’ It was so funny. They played ‘Scarlet Begonias’ and Buddy was singing along in the drunken stupor. It was chaos, and it was classic Sublime. The party’s on stage, off the stage, around the stage, everywhere.” I can’t deny how fun that would have sounded had my friends and I known about Sublime in their heyday. We embraced that kind of drunken pandemonium during our teens and early twenties, drinking beer and smoking tons of weed and gobbling mushrooms whenever we could. It made sense that Sublime’s record label named one short tour the 3 Ring Circus.

Like the original Iggy and The Stooges, Sublime could play an incredible show one night, and a horrid one the next, even play one killer song before slaughtering the next. You never knew what you’d get. Some people loathed that about them, including certain bands who watched them bumble through their drunken sets on Warped tour. Other people liked that. “It was a hit-and-miss thing for us,” remembered bassist Eric Wilson. “We used to drink a lot. A lot of my older acquaintances would say, ‘I would never know if you guys were going to sound like total shit or play great.’ We didn’t have our professional skills going on back then. We just thought the world was ours, or whatever.”

As promoter Lil’ Mike put it, “Of course, part of their appeal was the element of don’t give a fuck danger and unpredictability, which could play out in various ways. Whether it was a skate ramp in Sacramento or a near riot in San Pedro with no notes played…each gig was a thrill, and these were genuinely fun young guys to be around.” But that aura came at a cost.

They arrived late to gigs. They missed others. Botched interviews. Even got too trashed to do simple free recordings. The day after their Robbin’ the Hood record release party in 1994, Sublime opened for No Doubt in San Bernardino, and their tattoo artist friend Opie Ortiz—the dude who tattooed the word ‘Sublime’ on Nowell’s back and drew the famous sun on 40 Oz to Freedom—had to play drums because Gaugh never showed. At another gig, Wilson and Gaugh arrived so late that Nowell played part of the show solo, which people loved.

“People used to come to our shows and stand outside while we played our first song,” Gaugh told the OC Weekly in 2010, “just to see if we sounded like shit before they went in.”

“Or to see if we even showed up,” Wilson added.

Most of 1994 and 1995 was a blur of back-to-back performances in a different city every night, crisscrossing the country multiple times as headliners or as an opening band. In 1995, Sublime co-headlined the first Vans Warped Tour. At a drunken show in upstate New York, Nowell’s dog kept biting people, and the band got in a mud-ball fight with the audience, so management kicked Sublime off tour for a week. “Basically,” Gaugh remembered, “our daily regimen was wake up, drink, drink more, play, and then drink a lot more. We’d call people names. Nobody got our sense of humor. Then we brought the dog out and he bit a few skaters, and that was the last straw.” That kind of life wears people out. Home life was no tamer.

Back in Long Beach, Sublime would wake up to drinks and do breakfast bong rips. Sometimes they’d surf. Sometimes they’d skate, get tattoos or jam in the yard. It was the southern California dream, the lifestyle that many of us aspirational outsiders envy, especially young dudes in their teens and twenties who grow up skating, snowboarding, and yearning to live someplace cooler than home. Even if you didn’t like neck tattoos or shorts hung below peoples’ knees—and I don’t—how could you not envy these guys? Sitting outside on a long brown sofa at the Warped Tour’s Northampton, Massachusetts show, Nowell holds a draft beer in his hand and has his arm around Lou Dog, as he tells the interviewer that even though they’ve been working hard at their music for a decade, “None of us have ever had a real job, like, with the exception of Bud who used to work at a hardware store.” Bradley said that making the video for their song “Date Rape” felt like the start of something bigger. “I’m ready to do this the rest of my life, so this is the beginning of my career, so.” Unfortunately, like many of us wild city kids who found our identities in underground sports and music culture, hard drugs eventually made their way in the band’s life.

Gaugh went to rehab for speed and heroin in 1990, 1991, and 1992, when the band was trying to the tour the US with their first full album, 40 Oz. to Freedom. Gaugh’s mother remembers the horror she felt every time the phone rang at night in the band’s early days. She thought: Bud’s in jail; Bud’s in trouble; Bud needs bail. “He was drinkin’ way too much,” she said. She also remembers the relief she felt when the phone rang one time around 3am. “Hey mom,” said Bud, “I’m just callin’ to tell ya I’m not in jail.” Gaugh struggled to steer clear of the hard stuff after that, but it didn’t always work.

In June 1993, Bad Religion’s guitarist Brett W. Gurewitz let Sublime record demos at his Hollywood studio, for free, while he was away, because he loved their music. “When I got back from tour,” Gurewitz remembered, “the tapes were killer, but my partner said, ‘Hey man, these guys are drinking 40s and smoking crack in the studio.’” That freaked them both out, especially Gurewitz, who was trying to stay sober, but these demos ended up on Sublime’s second album Robbin the Hood and helped get them signed to MCA. That blasé behavior also helped put Nowell in rehab like Gaugh.

Nowell resisted heroin for a while. After he finally gave in, he went all in, believing it improved his creativity. Granted, he wrote some incredible songs that became Sublime standards like “STP,” “Pool Shark,” “Greatest Hits,” and “Saw Red.” He even tried to release a rushed, homemade demo named Chiva Kenevil, until his band-mates stopped it. They weren’t happy about his habit or the way his advertising of it appeared professionally. But from then on, heroin was an unwelcome member of the band and Nowell’s life, alternately a shipmate or an anchor. “It ran the whole show,” his widow Troy told the Los Angeles Times in 1996, while their one year old son Jakob napped in his crib. “Everything revolved around whether Brad was using or not. If he was not, it was a struggle to keep him from using. And if he was using, it was a struggle to help him quit.”

1993 though the 1994 recording of their Robbin’ the Hood album was a period of serious use. Things started disappearing from Bradley’s father’s house. When Bradley’s stepsister Katie Gibson came into her brother’s bedroom to search for her missing CDs, she found a bunch of needles. She kept those secret. After Jim realized why his son had lost weight and kept falling asleep while speaking, he forced him into rehab. Things kept disappearing, so Jim kicked out Brad, who started couch-surfing and staying with his friend and manager Miguel at various flophouses around Long Beach and Orange County.

One place where Bradley spent his time was a San Clamente house that meth users took over after an earthquake damaged it. People nicknamed it STP, for “secret tweeker pad,” and the band recorded part of Robbin’ the Hood in it, on some equipment they’d stolen during the 1992 L.A. Riots. Middle class from a nice home in an upscale, coastal area, Nowell was an intelligent, articulate, intellectually curious guy who enjoyed history books and getting into deep conversions with friends and strangers. And yet, he clearly romanticized drug use and bulked up his musical identity with the aesthetics of squalor. And he was naïve. When he and his future wife Troy first met at a show in 1993, he didn’t hide the fact that he was on heroin from her or other people. He would blurt it out.

“I felt like kicking his ass,” Bud Gaugh told Rolling Stone. “I mean, I’d been there and was still struggling with it. So I was all things that I could be to him during that time. I tried to be his conscience; I tried to be his nurse. I even tried to be his drug buddy; I mean, we got loaded together a couple of times.”

Few in Sublime’s social circle had much leverage, though. Theirs was a party culture. But in Troy, he found someone he could speak to candidly. She understood addicts. Both her parents had been speed users, and her childhood home was so frequently filled with bikers and drug users that she became drawn to them later in life. “I love drug addicts,” she explained to Rolling Stone. “I guess they’re just the kind of people I’m used to being around. They’re great; they’re crazy.”

Of course, Nowell would promise to quit heroin. Then he’d keep using. He’d even pawn the band’s equipment, let their manager Miguel figure out a way to buy it back on the day of a show, and the cycle would start again. He alienated his bandmates and family, burned his proverbial bridges. “It really consumed us,” Troy later said. “Not in a productive way, but in an angry, scared, fearful way. We were always afraid he was going to use again. Afraid that one day it would be the last time.” Brad went into rehab in 1994. “While I was pregnant, he stayed clean for six months, which was the longest he’d ever stayed clean,” Troy told OC Weekly. He struggled.

“He had a patch that was supposed to go on his back to sedate him,” a friend named Shea remembered, “and then he’d take off his shirt, and you’d see he’d stuck these patches all over his back. He was a mess.” Even during his clean periods, his environment never changed.

“It’s not that we didn’t put him in recovery,” Jim Nowell remembered in 2019. “It’s not that he didn’t recover. He just always went back to the music. I would always plead with him: ‘Don’t go back to that damned band, because that’s where your problems are, because everyone wants to party with you.” What changed was the band.

They got so popular, their song-writing so sophisticated, that MCA, a major label, signed them in the summer of 95. MCA’s lucrative advance released them from the need to sneak into Miguel’s school recording studio or set up in a drug house, no matter how much they enjoyed that cat-and-mouse game. It also attached many corporate strings to their disorganized wild lives. “He decided on his own that he wanted to go to rehab,” Troy told Rolling Stone. “He knew he had to get clean before the MCA thing could happen.”

MCA planned to release their major label debut, Sublime, on July 30, 1996. The label poured a lot of money into the band, sending them to Willie Nelson’s Texas recording studio and Total Access Studios in Redondo Beach, preparing marketing campaigns. MCA expected a return on their investment. People were relying on them. Sublime felt pressure to produce. Nowell and Troy bought an expensive beach house in a gated community on a narrow strip of sand in exclusive Sunset Beach, south of Long Beach. Before they even got married, Troy gave birth to their son Jakob on June 25, 1995. Nowell told people he had to straighten up for Jakob. Nowell planned to teach his son how to surf. And he was determined to make this new album the greatest album Sublime he’d made. “He wanted his band to have glory,” Troy said.

Things had gotten serious.

The band wasn’t known for seriousness.

When MCA paid for them to record at Total Access Studios in Redondo Beach in 1995, the band’s partying nearly ruined everything. “They went into a studio with [engineer] David Kahne and recorded ‘What I Got,’ ‘Caress Me Down,’ ‘Doin’ Time,’ and ‘ April 29, 1992 (Miami),’” Sublime’s co-manager Blaine Kaplan remembered. “The morning after the first night in the studio, David called both me and Jon [Phillips] at six in the morning and he was freaking out. He almost quit, he wasn’t going to finish it. The guys were raging, partying, hardcore. Jon talked him down, telling him, ‘I know things seem crazy, but I know they really want to make this music. It seems hectic now but once you get down to it, it’ll be cool.’” Three of those songs turned into Sublime classics, two of them became hits, but this was how Sublime approached everything: with a drink in one hand, and trail of havoc behind them. The fun, unpredictable reputation that created an attractive aura to their growing fanbase also made them unattractive to music industry professionals who understood the challenges of dealing with wild musicians, particularly one with a history of heroin use.

Complicating the physiology of opioid addiction was the way heroin got bound up in Nowell’s ideas about creativity and the strain of being a frontman. Jazz genius Charlie Parker had unintentionally propagated this false connection between heroin and creativity in the 1940s and 50s, when tons of Parker’s Bebop acolytes took heroin hoping they could achieve Parker’s level of creativity. They did not. During the 90s,for whatever reason, heroin was everywhere, too. Maybe Mexican drug cartels had expanded their opium-growing operations by then. Maybe they figured out more successful ways of smuggling it into the US and keeping prices low. Whatever the reasons, anyone paying attention to underground music in the 90s saw many talented people using, dying from, or trying to quit dope.

Andrew Wood from Seattle’s Mother Love Bone set this deadly decade’s tone when he overdosed on heroin in 1990, right before the band’s breakout debut album. The infamous GG Allin overdosed in 1993 a month before The Wonder Stuff’s bassist Rob Jones did. Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain and Hole’s bassist Kristen Pfaff died in 94. Heroin took the life of Smashing Pumpkin’s touring keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin in 96 and got their drummer Jimmy Chamberlain kicked out of the band he helped found. By 1997 dope was so epidemic that Portland, Oregon’s Dandy Warhols sang “I never thought you’d be a junkie, because heroin is so passé.” For all the lives that heroin claimed, many musicians managed to save themselves: Blur singer David Albarn; Everclear singer Art Alexakis; Pantera singer Phil Anselmo; Dave Gahan of Depeche Mode; Gibby Hayes of Butthole Surfers; Cris Kirkwood of Meat Puppets; Scott Weiland of Stone Temple Pilots. Bombarded with stories of so many users’ death or survival, Nowell came to believe heroin could enhance his creativity. Jim Nowell told an installation artist that his son “started using drugs as an experiment on his music … because of guys like Kurt Cobain and Shannon Hoon of Blind Melon.” Jim told VH1: “His excuse for taking the heroin was that he felt like he had to be larger than life. He was leading the band, leading his fans, and he had to put on this persona.”

At the time, popular alternative musicians like Kurt Cobain, Sonic Youth, John Cale, and Ministry had turned Beat Generation novelist William Burroughs, another icon of opioid endurance, into a punk icon. Burroughs wrote the iconic books Naked Lunch, Junkie, and Queer. He’d inspired a character in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, had fascinating ideas about the occult, the mind, magic, and authority. He created the influential cut-up method of composition, and he’d aged into a literary figure and intellectual who knew how to manage both his heroin habit and artistic career. He’d always enjoyed notoriety as a so-called high priest of pleasure-seeking and subversion, dating back to The Beatles, but he experienced a renewed interest in the early 90s. Nowell thought highly of Burroughs. Look, Burroughs’ life seemed to say, if you do it right, you can use dope and still make art throughout your long life, too! Never mind that Burroughs was a rare example. Nowell thought less highly of 90s drug causalities. Nowell thought less highly of 90s drug causalities.

When Blind Melon’s singer Shannon Hoon died from cocaine toxicity after an all-night bender in October, 1995, it terrified Troy. Nowell refused to acknowledge any connection. He thought Hoon was weak, telling Troy, “That guy was just stupid. He just fucked up.” Like Bradley, Hoon was 28 years old and had a child. According so Spin, “even when Nowell was shitting in his pants from the five clonodine patches he’d slapped on to help him kick, he couldn’t give up the illusion that heroin was indelibly cool.”

“He got this elitist attitude because he was a junkie,” Troy told Spin magazine. “He always used to say, ‘You guys don’t understand, because you don’t do heroin. …A lot of junkies are like that. They think they’re doing the most hard-core thing, sticking needles in their arm. We could say anything—‘We understand what you’re going through’—but we really don’t, and they know what. They like that.”

Some of us know. Like Nowell, many of us ’90s kids developed our own heroin habits during that very blasted decade. I’ve smoked, snorted, and injected heroin. I’ve craved it and pushed it away, laid with my eyes closed reminiscing about times I’d passed out, doped out of my mind, and I played music just to take me back to those euphoric moments, since after my arrest and probation, I couldn’t go back there in real life. I understand the hunger, and I understood the emptiness of both indulging and resisting, how neither delivers the satisfaction you crave until you’ve resisted long enough that one craving dulls enough to endure, and I know how that dichotomous life makes you hate yourself and crave escape even more. Thankfully, some of Gen X kids lived long enough to sort things out. The Baby Boomers we found so bland are now the people we’ve grown into: house, job, mortgage, kids. That life’s actually pretty sweet. Now we play music for fun and introduce our kids to the albums we jammed in our youth, and we work hard to keep our own kids from ending up with the same deadly disease we carry.

Nowell’s childhood friend Todd “Z-Man” Zalkins eventually had the opportunity to reflect, too. After years of partying, he succumbed to a 17-year opioid addiction. He’s now turned his sobriety into the center of his career as an addiction specialist. One of the first people Zalkins helped was Bradley’s son Jakob, when Jakob quit his own addiction to alcohol and weed. You wonder what 50-year-old Nowell would have thought of his son struggling like he did, or his friend marketing himself as a counselor and public speaker. Old age fucks with you that way, but often in a good way. For example: Gaugh now plays drums in a kid’s band named The Jelly of the Month Club, with Burt Suzanka from the The Ziggens, a band that Bradley loved.

Even as Bradley challenged his limitations, he recognized them. As he sang, “The boss DJ ain’t nuthin’ but a man.” Whatever resolve Brad developed in late 1995 dissolved after MCA sent the band to record the rest of their self-titled debut at Willie Nelson’s beautiful Pedernales Studios outside Austin, Texas, in February 1996.

“They’re the sweetest bunch of guys,” producer Paul Leary told Rolling Stone, “[but] it was chaos in the studio. …There were times where someone had to go into the bathroom to see if Brad was still alive.” According to Rolling Stone, “On good days, they’d show up at 9 a.m. with margaritas in one hand and instruments in the other and go to work; on bad days, they nearly burned the place down.”

Partying was their reflex. They were also stressed. “Brad felt a lot of pressure for the self-titled album,” Troy told VH1. “He didn’t have a lot of songs written when he went out there to start recording it.”

Studying their track list closely, I can sense that: Sublime seemed determined to deliver strong tunes on their major label debut, so they did one of the things they did best: repurposed some of their old songs, combined bits of existing reggae they’d been jamming for years, and mixed their ideas with other peoples’ music. They repurposed a previously released jam called “Lincoln Highway Dub” and remade it into a song with lyrics called “Santeria.” They turned their very old song “Fighting Blindly” into the new fast song “Burritos.” “Caress Me Down” is an almost pure cover of Clement Irie’s original early 90s reggae song “Caress Me Down,” with the same name and same chorus, but some different lyrics about Sublime’s own lives. They built Half Pint’s 1986 reggae song “Loving” into “What I Got,” just as they’d previously used the baseline in reggae musician Courtney Melody’s “Ninja me Ninja” as their baseline on “Garden Grove,” the opening track on Sublime. They mixed The Wailers’ 1965 song “Jailhouse” with the lyrical structure of Tenor Saw’s song “Roll Call,” to create their song “Jailhouse.” The Wailing Souls’ 1984 song “War Deh Round A John Shop” became “Pawn Shop’.” Sublime made them their own.

Their song “Doin’ Time” is arguably the ultimate example of their approach: it mixes a sample of George Gershwin’s song “Summertime,” performed by jazz flutest Herbie Mann live, with Beastie Boys samples and a 16th note reggae beat by Marshal RAS MG. Then Brad sings over it. Jon Phillips, who signed Sublime to MCA and managed them during their third album, breaks down the brilliance of Sublime: “It was one of those situations where the band, in true Sublime style, the music that they were making—you can tell from 40oz to Freedom and Robbin’ the Hood before it—sampling and interpolations were a big part of their craft. And like a lot of great lyric writers will allude or even take a passage from somebody who came before them, Brad did that with music, and Sublime’s music became an amalgamation of a lot of things that came before it.”

Nowell is an example of a brilliant musician who could have written about anything, but drugs became central motifs in his material. Drugs are not the reason he was talented. He played well despite the drugs. But his struggle with drugs are a major force behind some of his most emotionally fraught performances and lyrics.

Bradley rewrote “Pawn Shop” to tell the story of his secret life: stealing and pawning the band’s equipment to score dope, and letting their manager Miguel figure out a way to buy the equipment back. “Down here at the pawn shop / What has been sold / Not strictly made of stone / Just remember that it’s flesh and bone.”

“Garden Grove” tells of “Waking up to an alarm / Sticking needles in your arm / Picking up trash on the freeway / Feeling depressed every day.”

“Pool Shark” is the most blatant. An ode to addiction, its candor is haunting. “Now I’ve got the needle and I can shake, but I can’t breathe / I take it away / but I want more and more / One day I’m gonna lose the war.” Nowell makes it easy to read his lyrics as prophetic, to claim that he knew he would die, but most intravenous drug users acknowledge the dangers. The way he sings it, though, holds the true pathos. It’s haunted. His delivery, so charged.

Other songs are subtly about death. In their cover of the reggae song “Great Stone,” Bradley sings: “It shall be done, all my troubles and triumphs. When I get over, over on the other side. I’m gonna shake my hands with the elders. I’m gonna tell all the people good morning. Burn my telephone trial list, yes I will.” The great stone is a headstone. He’s singing from inside his grave.

In “Badfish” he sings that he’s a parasite that creeps and crawls as he steps into the night. “Lord knows I’m weak / Won’t somebody get me off of this reef.”

The central idea of the song “Same in the End” is very morbid, a kind of fatalistic giving up: why bother, what’s it matter?

Seemingly playful on the surface, “Burritos” lists all the fun things he refuses to do today, because we assume, he’s depressed: “I ain’t gettin’ out of bed today.”

Among the bullshit lyrics about making a girl bleed, “Seed” contains prophetic thoughts about the dubious prospect of aging:

Well, if you live you wanna give or get old

And if you never knew that we get old

Live it up, you live it up, you get old

Believe, believe me when I say

That every people it’s the same shit everyday

But I got to know my place

And if you can’t it smacks you in your face

And then there’s “Johnny Butt.”

Secret Hate formed in Long Beach in 1980. In 1983, they recorded “The Ballad of Johnny Butt” along with an album worth of material. Then they broke up by 1985. Like many kids in the area, they’d gotten into drugs and into trouble. Their guitarist Reggie Rector eventually got murdered. Local musicians at the time cited them as influences, but Secret Hate never earned much reputation outside the area. They were, as Mark S wrote, “one of many bands who released one great album, contributed a few tracks to various comps, and unceremoniously faded away, disappeared into time, and were forgotten.” Same with the Long Beach punk band Falling Idols, who formed in 1981 and started to unofficially fade away by 1985 without ever officially disbanding. Both bands left their mark on Nowell. In college at UC Santa Cruz, Nowell had a 1982 compilation called When Men Were Men And Sheep Were Scared, which included two Secret Hate songs and two Falling Idols songs. He learned them on acoustic guitar, and Sublime eventually covered songs by both bands, in concert, in practice sessions, and on their albums. The tape probably led him to Secret Hate’s small back catalogue, where he found “The Ballad of Johnny Butt.”

Secret Hate’s original version is a cool, fairly simple impression of The Clash, mixing punk rock energy with ska guitar licks. The original is about kids being silenced and harassed: “Shake him up / Shake him down / You know it’s not that right / Johnny says he’s gonna go and do it, he says I want to kill a cop.” Overcoming authority and living in “A time when we find a right to exist” is a pretty standard 1980s, Reagan Era punk storyline, especially by white kids. Bradley heard something else.

By the time Sublime played KUCI’s Ska Parade show on March 5, 1994, he’d transposed his own issues onto it: “Shoot it up, shoot it up / It just don’t matter / When you’re resisting anyway!” His version is about overcoming, too, except against an internal oppressor.

Now “Johnny Butt” is to Sublime what the Meat Puppets’ “Lake of Fire” is to Nirvana. Ever since Nirvana played “Lake of Fire” on their 1994 acoustic album, people think it’s one of Cobain’s originals. It’s the Meat Puppets recorded it in 1984. People assume the same about Sublime’s “Johnny Butt.” Covers are often a questionable idea: Why recreate something that is already perfect? It’s a gamble. But the best covers don’t simply recreate the original like some Realist painting. They transform the original into something new, something that reflects the other artist’s own image.

By the time Sublime played Ventura’s Majestic Theater on November 9, 1995, Nowell had his lyrics dialed in. It’s a simple song: mostly three bar chords. Eric’s bass carries it. It’s sad, serious, and weirdly short—more like a sketch or fragment than the usual verse-chorus-verse pop song. It runs for 2:11 minutes on the Sublime album. Most live versions last around 1:55. By Petaluma, he’d eased so far into the song that he inhabited it. He no longer sang it stiff in 4–4, no longer fumbled over verses. He stretched it to a full 3 minutes and learned to pace his delivery in a way that allowed great emotional range. Secret Hate may be Long Beach legends, but Sublime’s version is enduring art. The band’s last live version is the most powerful there is.

Eventually, the band’s partying brought their Texas session to an abrupt end. “The amount of time that Brad spent shooting up started turning into long periods of time where I didn’t know if he was okay or not,” producer Paul Leary remembered. “It came a point to where it scared me and I just called the label and said, ‘Bring these guys home.’ They were scaring me, and Brad was scaring me, and I didn’t know what to do.”

Things worsened after a woman showed them all the pills they could easily get from Mexico. “They came back with hundreds of Valium,” said engineer Stuart Sullivan, “and that was the end. That was when it all started to crater.”

Paul Leary felt bad and conflicted. “I didn’t know what to do. Do you say, ‘We can’t make a record, let’s wait,’ and nobody works and everybody’s left hungry? Or do you make a record and wonder if you’re exploiting a junkie, or—It’s not easy working with a junkie.”

When Leary finally told Bradley that he had to go home, he fired Leary and Stuart and everybody else.

MCA sent Bradley back home five weeks into the session, days before they would have finished. Troy had never seen him so strung out. Frustrated and concerned, she moved herself and their infant son out of their new house and back in with her mom. She didn’t want Jakob around his dad in that condition. Bradley’s father came to his Sunset Beach house, where Bradley apologized for disappointing him again. Jim Nowell had never seen his son in such bad shape. “It took him three days to get back on his feet,” Jim Nowell told Rolling Stone. Hugging in the kitchen, his father told him, “I couldn’t be prouder of your music and all the things that you’ve done, but at the same time I’m definitely afraid you’re going to kill yourself.”

As Bradley sings in “Badfish”: “Baby you’re a big blue whale / Grab the reef when all duck-diving fails / I swim, but I wish I’d never learned. Water’s too polluted with germs.” The metaphor becomes so clear in hindsight: It’s about feeling stuck, not about swimming. “Lord knows I’m weak / Won’t somebody get me off of this reef.”

Brad voluntarily went into rehab. Along with recording and production, MCA is rumored to have poured upwards of half a million dollars into Bradley’s rehab alone. That came out of the band’s advance. Some claim that Nowell’s rehab helped put the band so deep into debt with MCA that, after he died, the first single big check Gaugh and Wilson received was a combined $2,000 from a fan’s bootleg CD release. They owed MCA money and had no income without the shows to play. Nowell did emerge clean and stayed clean for possibly three months. “It was the happiest I’d ever seen Brad,” Troy remembered. He spent time with his infant son, spent time with his parents, time on the beach, carrying Jakob in a baby backpack. As a father myself now, seeing the photos of he and his son together kills me in a way it didn’t when I first saw the photos in the late-90s. From the distance of a fan, it looks like the last best time of his life, the only time he’d get to spend with Jakob.

Feeling hopeful, Nowell and Troy planned to get married that May. The band returned to Texas in March to finish the album, and the band resumed touring that spring. As usual, the circus followed.

The road is not an environment that encourages healthy living, and the road stretched infinitely before them. The band was scheduled to begin their first European tour, in Saarbrücken, Germany, on June 1st. MCA scheduled their album’s release for July 30, 1996. As Bradley had sung at their recent Texas session: “Daddy was a rollin’, rollin’ stone / He rolled away one day and he never came home.”

Bradley was clearly an intelligent, thoughtful person. From what few interviews exist, you hear his intellect, wit, and humility. Of all the band members, he gives the most thoughtful, articulate answers. Eric barely talks. When he does, he mumbles or jokes. Gaugh can answer serious questions but prefers to fuck around. But Nowell makes excellent points and historical references, even frames the Hong Kong Phooey cartoon character through the lens of Greek tragedy. I wish fans had more opportunities to listen to him think.

In 2018, the OC Weekly published an article entitled “On What Would Be His 50th Birthday, Bradley Nowell’s Spirit Finds Sublime Reincarnation.” In it, the author speculates about what Nowell and Sublime’s music would have been like at middle age. It also describes him as “a front man that was both charisma incarnate and a shy, well-read introvert who never quite knew if what he was doing would catch on.” That’s a welcome contrast to the band’s beery image.

It’s hard to imagine the shirtless dude jumping around on stage as an introvert, but he was a complex person whose depth reached far beyond a rock ’n’ roll lifestyle. Another unfortunate side effect of his addiction was that he didn’t live long enough to give many interviews where he talks about his songwriting process or ideas about art. At the KROQ Weenie Roast in 1995, he did tell an interviewer that he wrote their popular song “Date Rape” when he was 19. “You know why I wrote it?” Nowell says. “I wasn’t even in a band or nothing. I was just messing around with the guitar, writing something I thought sounded cool. Go figure, right? I guess it’s because it’s straight from, you know, a spontaneous type of thing, like I was trying to say. Makes it all good. I wouldn’t say it was [about] anything. It’s just this song that I think rhymes, that’s cool. I liked the way it went. I wasn’t trying to say anything. If anybody else wants to say something about it, that’s their own problem. I guess everybody’s gotta say something, right?”

An interviewer on the Warped Tour asked about this popular song too, wondering if people misunderstood the lyrics. “Oh, most likely,” Nowell said. “If I could write more songs like that to make people just at least get off their butt and think about somethin’, damn, I’d do more. But it certainly wasn’t one of those songs where you can just reach down into your soul and make a statement. No. Sorry.” Meaning, you can’t engineer depth. Your best songs are often accidents, or at least, they start unexpectedly if you jam a lot. Good songs take time, luck, and come from mysterious places. Nowell had many deep places inside his surfer exterior.

“Whenever he’d write something new, he’d play it over and over again and go, ‘Do you think people are gonna like it?’” Troy told the OC Weekly. “He was never totally sure; he couldn’t really see it through other people’s eyes.”

At that KROQ Weenie Roast, Nowell sits on a long couch next to Gaugh, their friend Z-Man, and Skunk Records co-founder Michael Miguel Happoldt while an unseen interviewer tries to ask him serious questions about their music. Gaugh lights a joint. Porn star Ron Jeremy stands behind them. Z-Man interrupts, asking if they’re interviewing them or him. Nowell laughs and plays along, letting his dog Lou lick his face, but he also tries to give her thoughtful answers and pay respects to the alternative radio station who played “Date Rape” enough to help build the band’s popularity. Everyone else was goofing off, waving beers and joints at the camera, talking over him. Nowell finally had to cover Bud’s mouth and tell a rambunctious Z-Man, “She’s talking to me goddammit.”

Thankfully, Bradley is determined to get a word in. Asked about filming the “Date Rape” video, Bradley says: “I think we’re gonna do videos for the rest of our lives and keep writing songs till the day we die, pretty much. Been doin’ it since we were 13, right? Hahaha. How we gonna stop now?”

Behind him Z-Man yells, “Somebody call Dominos pizza!”

Gaugh reclines on the couch and says, “I need a large sausage with extra cheese.”

In March, the Sublime circus rolled through New York City, Philadelphia, DC, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago. On April 30, their tour returned to California, taking them to San Francisco, Orange County, Santa Barbara, Las Vegas, and Santa Cruz. Troy and Bradley got married in Las Vegas on May 18. On May 23rd, Sublime played an open-air show at Plaza Park in downtown Chico, at an event called Cheekopalooka, a combination of the words Chico with Lollapalooza with a type of buffoon called a palooka.

“That was one of the most insane, crazy rock ’n’ roll shows I’ve ever seen in my life,” booking agent Rick Bonde remembered. “There were probably 2,000 people there. The fence got torn down, security was overwhelmed.”

“It was in a park,” Eric Wilson said, “with a traveling circus. All these people with tattoos and piercings, the freakshow thing.” For an opening act, one of the Jim Rose Circus guys pushed nails through his nose and swallowed swords on stage, but the other show was off-stage.

“At one point I saw an opening in the crowd and I thought someone had gotten hurt and gone down,” said Rick Bonde. “So I jumped off the stage, right in the middle of this crowd, and there was nothing there, but everyone was looking on the ground. I’m like, ‘What are we looking for?” And some guy yells out, ‘A finger! A fuckin’ finger!’ And I’m like, ‘What do you mean, a finger?!’ So we’re all there looking around for this guy’s finger.”

Chico was arguably California’s number one party school at that time. According to Bud Gaugh, the Chico show’s promoter “offered us a veritable smorgasbord of every drug under the sun,” Bud Gaugh recalled.

“At the afterparty,” Bonde said, “Brad came up to Mitch, who was the bodyguard we’d hired to protect Brad from himself. Brad walked up and said, ‘Gimme some money.’ And Mitch was like, ‘No, I’m not giving you any money.’ And Brad got really upset and was like, ‘It’s my money! Gimme my fuckin’ money!’ And Mitch was like, ‘I’m not giving you any money.’ Because we all knew what that was about. But the unfortunate thing is that Brad didn’t need money to score, you know what I mean? So I’m convinced he got it that night.”

“We stayed over at some college girls’ house and smoked crack for breakfast,” Wilson remembered. “So it wasn’t really surprising that that’s where Brad found his last bag.”

Johnny Butt could not resist.

“He wanted to party one more time to kinda celebrate this album release,” Gaugh told VH1. “Both Eric and I had both told him, ‘No, you don’t need that.’”

“I slept hungover on the way to Petaluma,” said Wilson. “And so did anybody else that was in the van. We had a big old junker motor home and we had our own bunks. That was like a tour bus to us.”

Sublime headlined at Petaluma. Fillibuster opened, followed by Sublime’s friends from Orange County, the genre-hopping Ziggens. The bands had been playing together since at least 1989. At shows, the Ziggens often performed Sublime’s “Badfish.” and Bradley loved playing The Ziggens’ “Big Salty Tears.” Their relationship was as much a friendship as a mutual musical appreciation.

“We had a 27-foot 1967 school bus that we took around on tour,” said Filibuster singer Jason Boggs, “so we rolled up in that, and all the guys from the band hung out in there. That was like our little backstage party zone.”

“I remember lots of frat boys,” said Hollie Simons, who was 19 at the time and drank beer from a 7–11 Big Gulp cup, “which was weird for the Phoenix, and the crowd that usually went there. It was never the college boys, it was the punk rockers and skaters. I went with my girlfriends.”

“Brad was hanging out with people out front,” said a young fan named Tyson Engel. “He was excited with the new record coming out. I gave him a cigarette, but I didn’t really talk to him that much.”

“I thought it was incredibly cool that before they played, Brad was in the crowd, drinking and hanging out,” said Hollie Simons.

But a few people like Tom Gaffey noticed some differences. “The first couple times that they came through, they’d get here early, they’d do their soundcheck and then they’d hang out with all the skater kids. The skater kids would be going onto their RV and watching videos with them and hanging out. The last time through, the RV was not open to skaters. They weren’t hanging out as much. Bradley wasn’t skating with the kids like he had before. That was the first sign that something was a little bit wrong.”

You hear the weight of all of this in Nowell’s delivery of “Johnny Butt.”

Gaugh usually starts this song with a drum roll, which Wilson and Nowell follow. In Petaluma, Nowell starts with a dark guitar chord. It is eerie, almost gothic, and clashes completely with the usual punk ska flavors. He seems to be checking if his guitar’s in tune, or testing his effects. He probably didn’t even think of this as the song, just the warm up between songs. The dark note only rings for a few seconds, clearly an afterthought that Nowell tossed off, but attached to what follows, it becomes a new intro for a song they’ll never play again.

After the chord fades, Nowell strums the song’s basic three-chord sequence. The guitar is drenched in reverb, so it rings out like a ghost, chillingly, spookily, into the night. It sounds nothing like the Clash type song that Secret Hate wrote, just a slow deconstruction of it. For once the guitar isn’t buried under lyrics. Now free for all to hear, the sound hangs in the air, and Nowell drags his fingers down his guitar’s neck into the higher registers, releasing a squeal that sounds like a ghoul’s. The place turns strangely silent. No one talks. Only one distant voice screams after a few quiet seconds. It’s as if Bradly himself stood alone on stage, and the sound had commanded everyone’s attention.

Nowell plays that chord sequence again, this time without reverb. At that, people start howling, excited that another song’s about to start.

Nowell is clearly just screwing around before getting the band’s attention, but these throwaway 46 seconds turn into some of the most stirring, darkly evocative music he left behind. It feels personal. And it’s a taste of the musical directions he could have gone had he lived to write another album. In it, I hear hints of the seasoned, mature musician he was turning into: complex, sophisticated, moving beyond dub and ska, beyond genital references and easy laughs, into tender and unsettling territory, experimenting with guitar effects and new ways to play melodies, maybe simpler ways. Because no matter what you think about the bros you associate with it—the joints and suns and whole fuck yeah, whateva whateva of it all—this live version is a glimpse of an authentic songwriter who was evolving. Of course it’s speculation. Maybe he would have fallen so far into addiction that his songwriting would have suffered the way so many musicians’ had, like Crazy Horses’ guitarist Danny Whitten, who died just as he was getting started with Neil Young. Or maybe heroin would have left Nowell to even leave the house, like Alice In Chains’ lead singer Layne Stayley, who disappeared despite his success and died alone at home.

Underneath the guitar, Bradley says “Yo” to someone, maybe Eric. You can’t tell. He seems to be trying to get the other guys’ attention to let them know he’s ready, because Eric plays the chorus’ melody on his bass, slowly, as if eulogizing it, before Bud hits the drums and the band kicks in.

Bradley starts singing quietly, at a whisper: “Johnny Butt was a man with a real strong will to survive. He just kept pushin’ on even though he was barely alive.” Dub involves saturating vocals, drums, and guitars with echo effects, which make even the most sober listener feel stoned. When Nowell sings “barely alive,” the word “alive” trails into the background, bouncing off the theater walls like a spirit escaping a body. Matter-of-factly, he states, “Shoot it up. Shoot it up,” like he’s telling strangers directions: “On Fifth Street, to the left.” But when he sings those words, he’s dangling the secret he carried with him from Chico, up on to the stage.

He shouts the second verse with more force: “Johnny, just keep pushin’ ’cause the,” recounting his years, even encouraging himself to go on, before he dips down softly to sing “streets are yours.” Yours echoes behind him. Over yours yours yours yours, he unfurls the next lines sweetly, savoring his improvised variation on the melody as he finds the little pockets where the emotion lies: “And there will come a day when all that shit won’t matter.” That day, we think, has arrived. Again he whispers the deadly words, “Shoot it up, shoot it up,” trapped in the ritual of the lyrics, knowing where the song leads and knowing he has to follow its preordained course—three verses, three choruses, then out—even though destiny has not yet locked his own journey into place, that is, unless you believe in fate. Underneath him, Eric’s thick low bassline plods along, coaxing Nowell through the verses, leading the singer as if comforting him on his journey, as Wilson had in life. As the word “Up” echoes behind him, Nowell yells “When you’re!” before whispering “resisting anyway.”

It took me a while to notice, but the way Nowell starts quietly and raises the volume with each verse, builds tension that helps enact Johnny Butt’s story, and embodies the song’s emotional extremes: calm and enraged; peaceful and frustrated; sweet and screaming. Such attention to detail is another hallmark of a sophisticated artist, one who operates on the level of nuance. It’s not necessarily something listeners might hear—especially at a live show where people are distracted by the pit or their friends—but it’s something the singer feels and that registers on a emotional level.

As Nowell plays the chorus’ bluesy guitar lick, he sings: “We’ve got a brand new dance it’s called we’ve got to overcome.”

Here is not a man flexing his punk rock muscle, not a man showing how fast he can play or how funny on stage. He’s tearing down his walls to reveal his softest center. The stage held him there above the fans, but he was on their level, as wounded and needy as us all, broken and beautiful.

“Brad was so tired,” Troy told Rolling Stone the year after his death, “he really was. He was tired of letting everyone down, of letting himself down; he was tired of trying to stay clean, tired of everything.”

Although the band is only 27 minutes into their set, to me, this song is a career crescendo.

“Brad had accomplished everything he wanted,” she says. “He always wanted to have a baby: ‘We gotta have a kid,’ he said. He wanted to get his family back, ’cause he had hurt them so bad with his drug use. And he did. He wanted to get this album written, and he wanted it to be the best one he ever wrote. And he did. He wanted his band to have glory. And they did.” She lights another cigarette. “I’m not saying that it’s OK that Brad died, because it’s not OK. So many things have happened that I wish he could see—Sublime being nominated for awards and their videos being on MTV all the time and their songs played on the radio. Or things will happen with me, and Brad’s the first person I want to tell, ’cause we were best friends. I want to see his reaction to all this. What’s OK is [that] there’s no more struggle, no more war. That struggle took up a lot of our energy and our time, and it was horrible. He’s at peace now.”

For the third verse, he ratchets up the volume and belts it out. He sounds like he’s gargling broken glass in his throat. When he screams, “So, shoot up! Shoot it up!” you hear the desire, the fact that he wants to. Just like when he screams, “It just don’t matter,” you know he knows it does matter, but the longtime, impulsive, party-hound rebel wants him to think otherwise. I feel all of that in this performance.

As Bradley sings to “resist it anyway,” the word “anyway” echoes on top of the music, carrying on far longer than you’d expect, and clearer than you’d expect from a Walkman recording, as they finish the song.

We’ve got a brand new dance,

It’s called we’ve got to overcome.

Even if some attendees say the show was sloppy, that sloppiness may have helped Nowell’s delivery, loosening him enough to free him to adlib, rather than stick to the studio version, and in that experimental mode they found something potent. Their studio version of “Johnny Butt” is good but peppy. It still sounds like an upbeat, almost innocuous mid-tempo reggae-rock song. The music lets you dismiss the lyrics’ gravity. The slick fidelity does, too. Nowell’s vocals are mostly clean of effects. At Petaluma, he’s not signing it to get the best take. He’s singing it because he’s living it, right there that very night.

A handmade poster was taped to the wall over the Phoenix Theater’s moshpit, with the words “Play Nice In The Pit.” After the show, Badfish wrote that slogan on her cassette tape. Using money she made as a stripper, Badfish and her boyfriend, concert promoter Lil’ Mike, put five of those live Petaluma songs on an unofficial CD called It All Seems So Silly In The Long Run, which they mastered and released just before MCA released Sublime. “The band heard about the disc and called Revolver distro to get distribution stopped,” Lil’ Mike remembered, “but when they heard who was behind it, and that we had a limited number of copies circulating, they let it peter out and run its course before any lawsuits could get started. We truly did it out of love & respect and I think it shows in the care we took making it; and why people still contact me about it over 15 years later.”

Some fans kept asking Lil’ Mike for a copy of the whole recording, and once he gave them a copy, it started appearing online and on a bootleg that took that motto Play Nice in the Pit as its name. The recording is considered an important piece of Sublime history. To me, it also contains sublime beauty. Thank god for fans who go through the trouble of taping their favorite bands, and for circulating it with other fans.

By chance, the band seems to have professionally recorded their final concert, too. In 2006 they officially released a posthumous three-CD box set called Everything Under the Sun, which included demos, outtakes, live tracks, and tons of unreleased music. It included their five-minute soundcheck from that night, a propulsive, upbeat jam that mixes a slow dub with an instrumental version of what become their hit song “Santeria” with some of “Caress Me Down.” Before the recording ends, you hear Nowell telling the engineer, “We all done? We’re cool, too.” Officially named “Soundcheck Jam,” the fidelity sounds tinny but it’s still fun. This suggests the band has a recording of the entire show. Why would Skunk Records tape the soundcheck and not the rest of the performance? A board tape of “Johnny Butt” would be a huge improvement from the audience recording. No one can say if and when the band will officially release it.

According to the LA Times and a super fan named Eddie Villa, who shares rare Sublime material on YouTube, Skunk filmed part of the show, and a DJ named Albino Brown filmed the whole thing. An early advocate of the band, Brown DJ’d at KUCI 88.9 FM in Irving, California and had Sublime on his Ska Parade Radio Show a few times. Unfortunately, Brown’s footage from Petaluma got snarled in controversy with Nowell’s family and Skunk Records, who represented the band. After Nowell died, Brown tried to get them to sign a letter before he shared the footage with them. Skunk and Nowell’s family took that as insult. They were grieving. Couldn’t he just share the footage of their deceased son and friend? The bad blood remains, and Brown has never released the full footage. He might have showed it to a few friends. He seems to have finally sent Nowell’s family four songs. But during the last two decades, he’s kept it in his possession, doing little with it. Hopefully he digitized it to protect the magnetic VHS tape from decaying.

“I’m sure it’ll come out sometime,” Eric Wilson told KQED, “but I don’t know anything about the politics of it.”

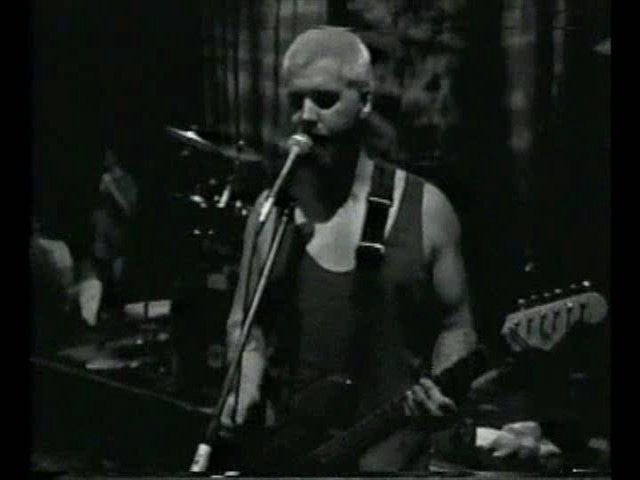

Thankfully, Brown licensed a few snippets to VH1 for their Sublime episode of Behind the Music. It’s black and white, and fans have frequently recycled it, slowing it down, freeze-framing, and looping these few precious seconds to pair images with audio on YouTube. Stretching what little material they have creates these jittery sequences that make the images even eerier.

VH1 features Brown’s footage of the band closing the show with their song “Work That We Do.” It’s another hypnotic mid-tempo jam, with lyrics about how playing music is their job. Nowell sings the line “Is it ever going to be the last show?” Instead of just singing the next line as usual, though, this time he first screams “No!” Then they left the stage for good.

“It was always a scene backstage,” Eric Wilson remembered. “We had our guard down, so we didn’t see what [Brad] was up to.”

Sublime and the Ziggens were scheduled to play together at the Maritime Hall in San Francisco the following night, so the band got rooms at the Oceanview Motel. It was right near the beach, on the western edge of San Francisco, just south of Golden Gate Park. Brad and Bud shared a room. Miguel got his own room. Eric slept in the RV out front.

VH1 says Nowell had been clean for three months. Co-manager says he’d cleaned up on April 30. VH1 says Bradley shot up before the show. These conflicting accounts no longer matter.

What we know is that Nowell called Troy after the show: “He called me and he was just so happy, and he wanted to tell me how much he loved Jacob and me, and that they had the best show ever that night. It was the happiest I had ever heard him. I could tell that he’d been partying, you know, and I was a little concerned. But I didn’t want to argue with him, because he was so happy.” Heroin has that effect. As she’d said elsewhere, “And the thing that was so horrible is that when he would get high, he’d be so euphoric and so happy. I was like, ‘Why can’t you be this happy when you’re not on it?’”

After the show Brad wanted to keep the party going. He tried to lure Bud outside with him sometimearound2am, but Bud refused.

“He asked me if I was gonna go out and party with him and, you know, I just wasn’t into it. I was tired. And I didn’t want to egg him on or support him in using.” Bud: “Brad tried to convince me we had all the reasons to party & it was worth celebrating, ‘We owe it to ourselves,’ I can remember him telling me. It was 2:00 am & I declined, falling asleep, Brad left to go walk on the beach with Lou Dog.”

Troy said, “His whole attitude was, ‘Look at everything we’ve got—I can have a reward every now and then.’ He wanted to reward himself. It was like, ‘I’m not hurting anyone, I’m just doing it this one day.’”

Although Gaugh doesn’t talk about it in subsequent interviews, Gaugh admitted to one reporter that when Brad had left their room that night, he’d stolen some of Brad’s dope, shot up, and passed out in bed. Brad walked the beach until sunrise, doing who knows what. Ten-foot waves were crashing on the shore, and as the sun lit the sky, he tried to wake up his friends to get them to join him.

“Mikey,” Bradley told Miguel, “you gotta see this. You’re gonna trip. Can’t you hear it?’” Miguel could hear those waves like explosives, but he told Bradley to come get him later.

“Man, it’s beautiful out,” he told a hungover Eric. “Let’s take Louie down to the beach” Eric told him go away and fell back asleep. Eric was the last person to see him alive.

Around 4am, Bradley called booking agent and co-manager Blaine Kaplan to talk with his childhood party animal friend Z-Man, but Kaplan couldn’t rouse Z-Man enough to talk. He was wasted on pills and alcohol.

Brad seems to have taken Lou Dog to the beach, then went back to his room where he sat on the bed near a sleeping Bud and shot up.

Although he doesn’t talk about it in subsequent interviews, Gaugh admitted to one reporter that when Brad had left the room the first time that night, he’d shot some of Brad’s heroin and passed out in bed. When he woke up, he found his dead friend. “I thought I was in hell,” Gaugh, told the Los Angeles Times. “I thought, ‘That was probably supposed to be me.’ The Grim Reaper saw him lying on his side, saw the tattoos and thought, ‘That must be Bud.’ It was Brad’s turn, though.”

Gaugh recounted that “Brad was laying on the bed, and he had his feet on the floor and was undressed, and I kinda like started laughing, like ‘You know, huhu, you must’ve had a good time. You couldn’t even make it all the way into bed.’ I didn’t hear him snorin’, or groaning from his hangover or anything. Lou Dog was like curled up on the end of the bed, kinda like whimperin’, looking really sad. So I got up and noticed he had like a film around his mouth, some yellow and white foamy mucus, and instantly I knew that he had overdosed.” He tried to resuscitate his best friend, but Nowell was unresponsive. “I began crying out loud for help, ran downstairs & down the road looking for the rest of the guys. This was the worse news I ever had to deliver in my life.” The paramedics couldn’t save him. They pronounced him dead at 11:30am. The bus ride home was also “the longest bus ride of all of our lives.”

“I was asleep in the motor home,” bassist Eric Wilson told KQED Arts. “We woke up to have bloody marys, and I sent my friend inside the hotel to get some ice for the bloody marys. And he came back frantically crying.”

Even if paramedics saved Nowell in San Francisco, most users continue using. Nowell had overdosed before. Gaugh had, too. “We all knew that one day it would probably come to this,” Gaugh said. “It was always a question of when. …The problem with drugs is, they’re a one-way street. Unfortunately, this is usually where they lead.”

“I’m convinced he got it in Chico,” Rick Bonde said. “And here’s my theory. I think that Brad knew that he was going to be home, seeing his wife and baby in a few days, and I think that he got high that night and probably decided he needed to just finish it off so he wasn’t tempted to do it the next day. So he could clean up for a couple days before he needed to see his family. That’s been my gut this whole time, and believe me, I’ve thought about it a million times in the last 20 years.” It’s a reasonable theory. Quitting now was wise. He certainly couldn’t take a habit with him across the Atlantic to Europe.

Instead of a European tour, they had Nowell’s memorial. Friends paddled their surfboards out in the ocean from his and Troy’s Surfside home and sprinkled his ashes in the water he loved.

Burt Susanka, of The Ziggens: “In some ways you kinda knew something like this was maybe gonna happen. For years. But, you know, you’re never really prepared for it or anything like that.”

In the LA Times, Troy took the opportunity to tell readers: “I want to make people aware that this is not what being a musician is about. I want to tell kids that Brad had a gift long before he ever did drugs—but drugs robbed him of that gift.”

Artist-musician Opie Ortiz, who tattooed the word ‘Sublime’ on Nowell’s back, who drew the sun on 40 Oz to Freedom, and the flowers on the self-titled cover, and created what now stands as the whole Sublime design aesthetic, said: “He fuckin’ spit his heart and soul onto that album. That’s what we have. He wasn’t just, like, a guitar player-singer. He had a musical vision.”

“It killed part of me,” Eric Wilson said. “I don’t really like talking about it.”

On the morning of May 25, 1996, as Bradley’s family and friends were dealing with the horrible news, I was waking up in Tucson, Arizona, to my first day as a legal drinker. I wasn’t a Sublime fan. I didn’t know they had a big album coming out. I didn’t know anything about them. In those days, if it sounded like ska, I skipped it. I hated Mighty Mighty Bosstones, hated Rancid, Less Than Jake, Reel Big Fish, all that corny crap with horns. White boy reggae hadn’t yet led me back to the originators like King Tubby or Scientist or the legends Sublime loved when I saw the news on MTV: Sublime singer Bradley Nowell had died on the eve of their major label debut. It was the first time I’d heard of them. To me, he was one more musician that heroin had killed during my musical adolescence, and by then, I had smoked and snorted enough heroin that this news scared me. It wasn’t a loss of a band to me. It was a warning: quit while you’re ahead, kid. Despite coming of age in a decade decimated by addiction, I had to learn the hard way. During the next two years I got strung out. I got arrested. Twice. When the city of Phoenix put me on a year’s probation to avoid incarceration, I was grateful. The threat helped me stay clean and remain clean, and I now look back on those who were not too lucky and wonder if that person who scored dope daily was even me. It wasn’t until my first year of sobriety that I heard the pathos on “Johnny Butt” and realized that Brad’s proxy was my proxy, too. I’d become Johnny Butt. But I had lived to see it clearly.

Sublime’s co-manager Jon Phillips, who signed them to MCA, told a reporter: “It looked like the band was ready to explode. The stage was set for greatness.”

The band exploded without Nowell. Sublime came out on July 30, 1996, two months after his death. Within two weeks of its release, the first single “What I Got” became the most requested song on LA’s alternative station KROQ. Two months later, Bud Gaugh and Eric Wilson did three-days’ worth of interviews in New York City, with everyone from Newsweek to People to Time. Sublime was the perfect summer album. It still is. Things kept building.