In 1993, the year I graduated high school, a young woman took me for my first lunch at a natural foods store and changed my life. Her name was Jamie. We met on vacation in Newport Beach, California.

To reward my high school friends and me for graduating, our parents rented us a house right on Newport Beach for a whole week in May. It was a simple, one-story, three-bedroom house with janky blinds that wouldn’t fully close. Before the glass mansions sprung up on many of those beachside lots, long before developers added a second story to little old 1414 W. Oceanfront Way where we stayed—with gauche rock accents and ostentatious ceiling beams—Newport had many tiny working-class houses that would have looked at home in Reseda. Despite the lack of luxury, ours had a royal location: right on the boardwalk facing the beach.

As if it wasn’t obvious enough that we weren’t locals, a “Summer For Rent” sign hung above the entrance.

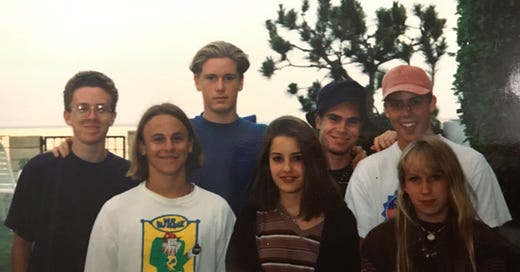

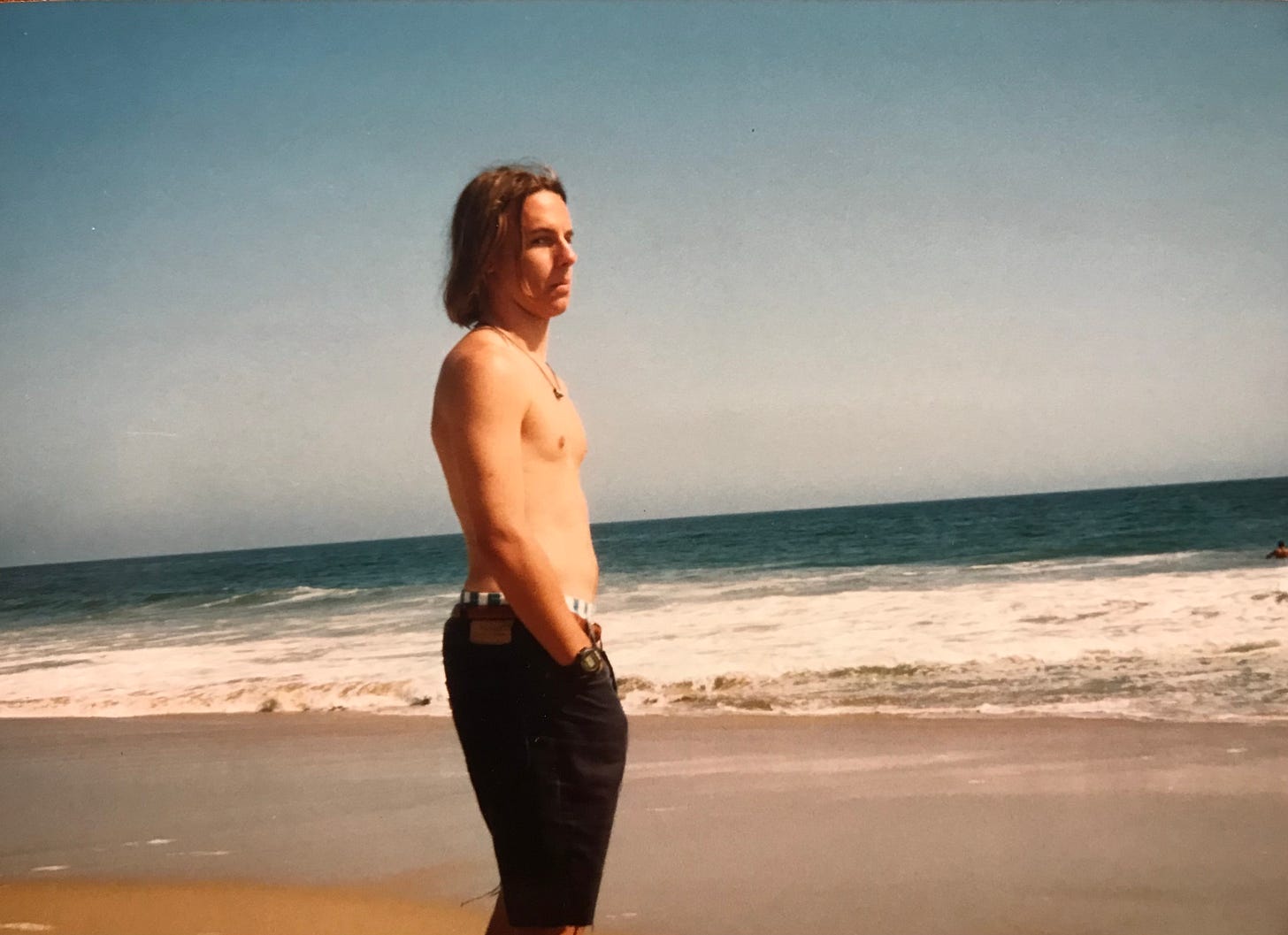

For one week, with no adult supervision, we were left to our own devices but were too nerdy to get in trouble. My friends Jeff, Alex, Ryan, and Rich brought cigars to smoke while playing poker. We brought board games, wetsuits, and boogieboards. Alex brought a few loose beers that rolled around in a box, but no one brought weed—not even me, and I smoked too much of it back then. During the day, we sat in the front yard, marveling at the endless procession of scantily clad bicyclists who passed on our boardwalk. We swam in the waves, flew a kite, and ate grease and junk food. Jeff spent a lot of time reading on the shady front porch, avoiding direct sunlight like some kind of vampire. Then we watched movies and the guys played poker at night. I never liked poker. I was the only one who didn’t play. We were the kind of kids who glued a quarter to the boardwalk and watched people try to pick it up, the kind who de-pantsed Rich when we ran into the ocean with all his clothes on. Cigars were our one indulgence.

While the Stone Temple Pilot’s Grunge-rip-off song “Plush” played constantly on MTV in the living room, some of us giggled about the prospect of all the beautiful women we’d get to admire from our yard during these dreamy days leading up to Memorial Day. We’d just spent the last four years in an all-boys Catholic high school in Arizona, deprived of basic interactions with girls, let alone campus courtship rituals or romance. That’s four years pining for girls we were unable to speak with in class. Our same-sex Catholic schools like Brophy College Preparatory believed that when you removed distracting sexual dynamics from campus, students could focus better on learning. Turns out that’s a dumb idea.

“What good is a homecoming dance when you have no one to dance with,” I wrote in a sophomore year English assignment. “I am not going to dance with a Priest.”

Students got smart. They took senior physics and Latin just to get in certain coed classes at the neighboring all-girls Catholic school. Ryan did. He met his first real girlfriend in coed French class. I didn’t have a serious girlfriend until senior year, and I’d taken physics just to share a room with smart young women!

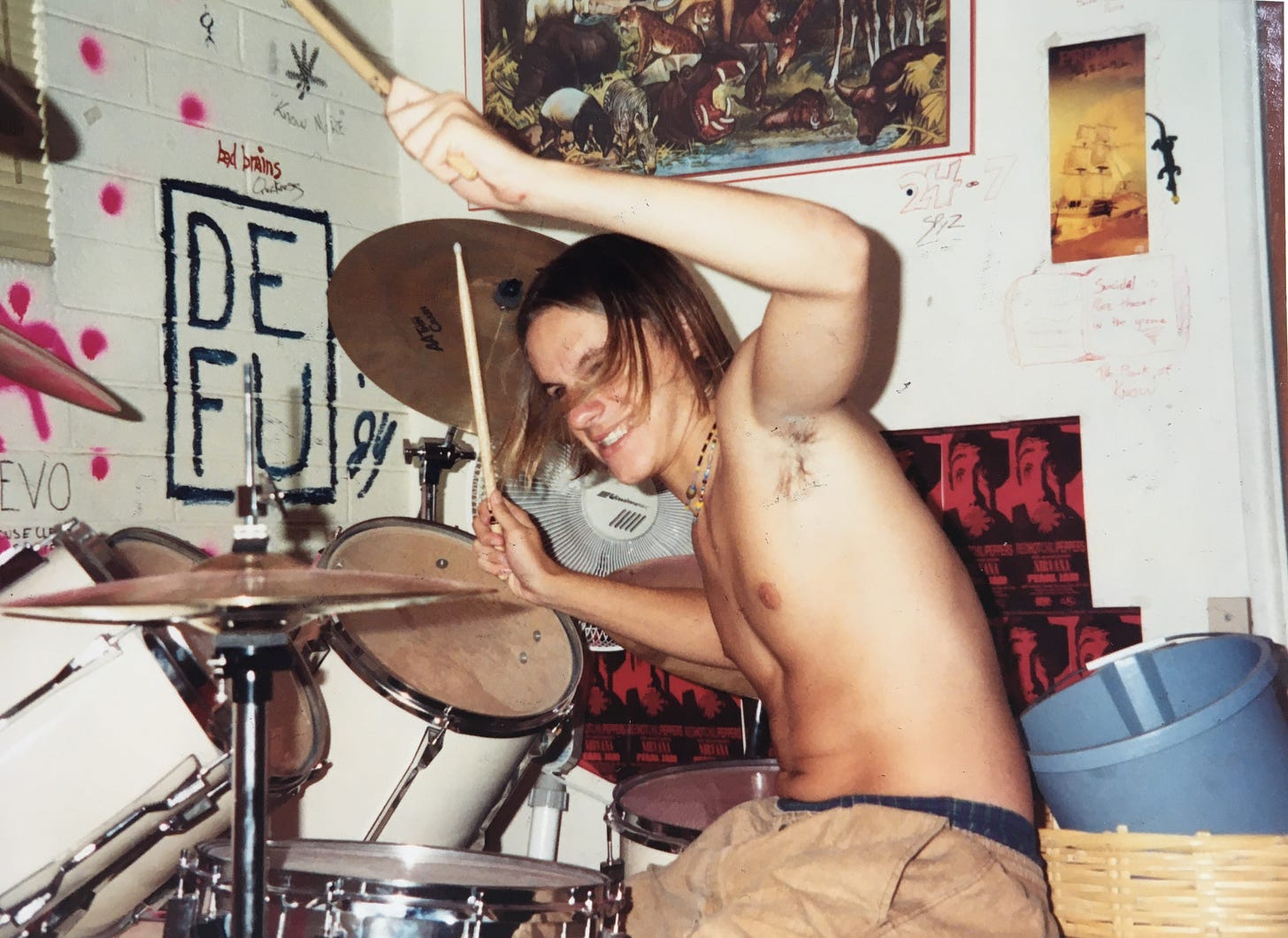

Although many Brophy boys were the beer-guzzling, sexist, sporty types destined to become frat boys with liver problems, most were just regular harmless kids like us. My crew was the kind who joked about robots and the name “Crab Nebula.” We laughed at words with hard consonant like ‘corn’ and regularly worked Star Wars into conversations. Although I was the raw, rock ‘n’ roll one who smoked weed and took shrooms and saw bands like Nirvana play, I also loved manga comics, and we drew pictures of creatures with tentacles that our crew gave names like Tenticulus and Mr. Meatmorph. My Brophy friends loved music, too, of course. Jeff had a full half-pipe in his backyard during middle school, which is serious shit, and more than I had as a skater. But he outgrew skating, and as we aged, we naturally changed, and their cool guy exteriors came on in college while I tried to mellow out.

In Newport Beach, we dorks soon noticed a young brunette and her friend over the low cinderblock wall that separated our front yards. The brunette and her mother either rented or lived in the small house next door—I can’t remember. I’m ashamed to say, but I’d forgotten the young woman’s name until Alex recently reminded me it was Jamie. Strangely, I never wrote Jamie’s name on the back of the three photos I have of her. But she is one of those strangers who, if you’re lucky enough to meet one of them in your life, make a big enough impact that you still think of them decades later.

I’m a 46-year-old father now, living in Oregon a 1,000 miles from Newport. During the many years when I couldn’t remember Jamie’s name, I thought of her as Beach Goth. Maybe Jamie wouldn’t have liked that nickname. Who knows what she would have liked. We only spent a few days together. As someone recently told me after hearing this story, she and all the other strangers who pass through our lives “will always be ageless in our memories, which is almost better than learning who they are now.” It’s true. She could be a Trumper now. She could have gotten decimated by the opioid epidemic or become a materialistic suburbanite with a five-car-garage. After all, it is Orange County. For me, she remains a singular figure in a life I’ve tried to constantly improve. I’d love to know how she is.

To state the obvious: Jamie was radiant. She had dark shiny hair, deep brown eyes, and lush red lips—truly model features—but she wore loose Hang Ten striped surf tees like I did and red Converse All-Stars like many of us alternative rock kids. Her presence struck everyone in our sheepish crew, and her poise probably intimidated them as much as it did me.

So from our side of the fence, here were these two young woman staying a few feet away from our vacation paradise but who we don’t know how to talk to. From the girls’ perspective, here was this excited pack of uncollared puppies on the other side of a wall that wasn’t tall enough to block their noise and advances. They probably wondered if we could be trusted. The girls quickly learned that we didn’t know what to do with ourselves. It’s embarrassing to image how long they may have watched us live our dorky lives in that yard: us rinsing saltwater from our scrawny bodies and wetsuits in the outdoor shower; us having loud conversations about Robosaurus, which was a real robot that crushed cars and breathed fire at monster truck rallies; us watching the quarter we glued to the boardwalk. After we noticed them, we probably simultaneously performed for them and ignored them, interacting from a distance without directly engaging. We didn’t know how else to impress them.

Then one day, we started nervously chatting over the wall. Hi! Hi. I’m Aaron. Hi. Do you live here? I mean, like, all year-long? That sort of thing.

Whatever we said, Jamie and her friend joined us in our yard. Alex compared their arrival to them landing deep in the Amazonian jungle and us being this dumbstruck woman-less tribe, like:

“Who is this mystical being?”

“It’s called a girl.”

Like Dark Vader moving silently through the corridors of the Death Star, Jamie arrived in our yard, beach sand grinding beneath her Converse in place of Vader’s flowing cape, and the place went silent. She nodded, held up an awkward hand, and quietly muttered “Hi” under a self-conscious snicker. She let the nervous energy hang in the air and seemed comfortable with it, arguably in control of it. Then the guys’ eyes lowered back to their poker hand. In hindsight, Alex wondered if she was as intrigued by us as we were by her: Maybe she’d never seen a group of such unthreatening, wide-eyed, ‘golly gee’ boys in rambunctious, punk rock, beer-and-a-joint SoCal before. Maybe our particular species mystified her: Cigars and poker and boogieboards? What kind of boys were these?

Um, we brought a kite?

Jamie and I started hanging out.

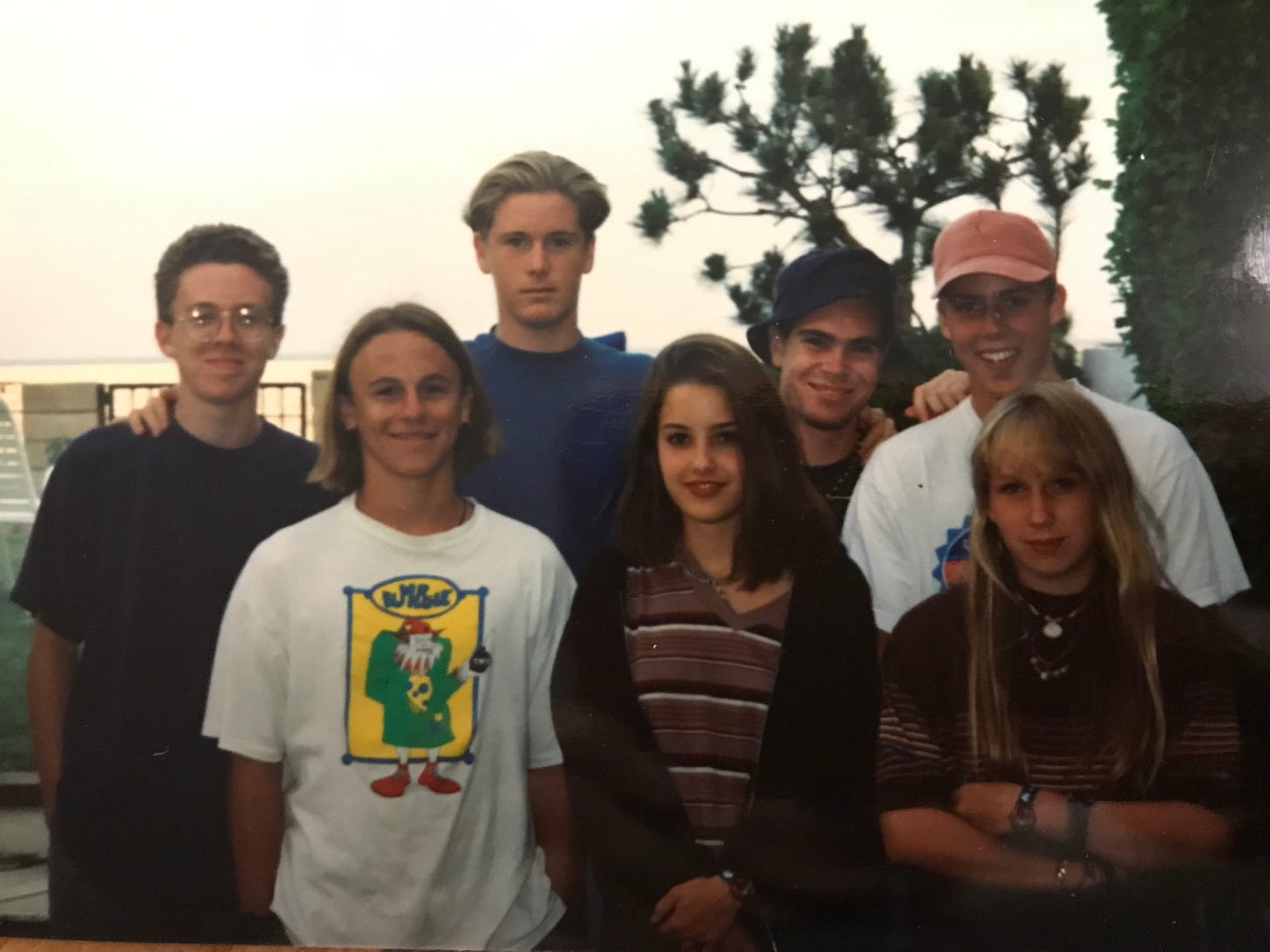

At age 18, I felt as comfortable in my sweet geek tribe as I felt at this beach. I’d been vacationing in Newport since a friend first took me there in fifth grade. In early high school, my parents and I used to stay in a little motel here for a long weekend each summer, eating Balboa Bars covered in nuts, and I’d spend entire days in the ocean, in a half-wetsuit, learning to ride large waves between Newport’s jetties. I even tried to boogie board the famously steep wave at The Wedge, until it slammed my head into the sand. I got pretty good at riding waves, though. The beach was my element, even if I spent the other 51 weeks of the year in Phoenix. Although I was a born subversive into visibly “cool” things—bands, beer, skating—deep down, I was a sensitive cerebral person, and I related to my crews’ sweetness, quirkiness, intellectualism, and sometimes their shyness. Teens are inherently awkward. I just housed these traits inside a rough, countercultural exterior, protecting myself under the kind of tough fuck-all skater shell they didn’t have. What seemed like contradictions were my nature. Maybe that’s why I had two groups of friends: my crew at my high school, and my crew outside of school. I am a Gemini after all.

My Catholic school friends are some of the smartest, funniest, coolest guys I’ve ever met. One was on swim team. One was a brilliant computer programmer back when that was niche. One loved drawing and music as much as I did. Coming from middle to upper-middle class families, everyone was expected to attend college.

My other friends were wilder, rebel types. I lived far from high school campus, so I already knew people from my neighborhood and had an existing local friend group when I started high school—friends I’d never been in a single class with. Those guys became my tightest friends, even when it was harmful. They came over after school. We crashed on each other’s bedroom floors on weekends. We skated. We went to rock shows. We drank beer, smoked weed, and took mushrooms for the first time together. My Catholic high school friends didn’t skate, they didn’t party, and they occasionally went to rock shows. Most of us weren’t even Catholic! We bonded in other ways.

At this point, I was perched between two worlds: The world of subversive, drug-taking partiers, and the strait-laced world of kids going to college to build respectable careers. I was just independent minded. And my natural curiosity applied to everything, from the scholarly to the subversive.

It’s funny how my high school classmates were alternately encouraging and concerned. “Let’s smoke what’s left of our brains away,” one classmate wrote in my senior yearbook. “Keep your brain healthy and alert,” Ryan wrote a few pages later. “Thanks for calling me this year...geez!” That hurts to read now. I was partying with my other friends and had let this relationship faulter. “I wish you good luck at ASU,” Jeff wrote. “Take care of your brain—it’s more valuable than you think. PS: lay off the buddha—you’ve already conquered cigarettes.” He was right. The smart kids could see my trajectory. Like every high schooler, I was growing, and I wasn’t entirely sure in which direction. Unlike others, I was open to both the destruction and the creation involved in growth, happy to steer my ship into to the rocks to get on any tantalizing shore. Besides needing to lay off the beer and weed, which wasn’t going to happen for a while, I guess I needed a way to protect my body from my diet.

This is what Jamie stepped into when we met.

Now that 30 years have passed, my memories could be wrong. But I remember she said her mother was an old school beach hippie, possibly one of those kinds who ate a lot of strong acid in the 1960s, which might explain why Jamie had gone a different direction and cultivated a slightly beach goth aesthetic much darker than you’d expect for a coastal town composed of tan, half-naked people. The Gothic part was more her aura than her look. She wasn’t a Bauhaus fan dressed in black leggings, black eyeliner, and black boots. She wore black eyeliner, but she presented as an average early-90s alternative rock girl. One day her friend wore five watches and lots of beaded necklaces over her striped tees. The watches were a fad thing. But Jamie had a quiet power about her, a brooding, watchful demeaner that reminded me of the stereotypical goth’s internality and cool, measured distance, even sophistication, which contrasted with what I thought of as the loud, outgoing, party spirit of a beach town. It certainly contrasted with me. I liked being loud. I mistook wildness for coolness. Beach Goth often hid her fair skin under a black baggy hoodie. Maybe all the bikini-wearing women made her self-conscious. Maybe she thought it was dumb to show so much skin. I’ll never know. What I know was that she was quiet, reserved, had that blinking watchful beauty of someone who observed deeply, had many complex ideas, and who accustomed to being subjected to the male gaze and appreciated breaks from all the unwelcome admiration. I would have fallen in love with her—I may already have—had we lived close enough to really get to know each other. I liked feeling the heat of her fierce intelligence. Her poise made me excited and nervous, but our conversations set me at ease. She seemed so genuinely cool. Next to her, I felt like an aspirant.

Back in Arizona I thought I was cool. Here on the beach, I was just another Arizona tourist taking up space, trying to earn my place in Newport’s big breaking waves. A few years earlier, I’d decorated my bedroom with ads and images I cut from surf magazines, because I was obsessed with surf culture, and hung the phrase “Summer is an attitude not a season” on my bedroom door. On this trip I wore concert tees along with baggy board shorts, Billabong t-shirts, and Rainbow brand flip-flops that I got at a skate shop, creating a costume that was meant to celebrate my beloved coastal culture and blend in. It didn’t. Instead, I looked desperate to advertise my interests—ooh, a Mr. Bungle t-shirt! How edgy and abrasive!—and looked like I bought my clothes right off the rack, which I did.

I was just starting to shop thrift stores, so I had both cut-off uniform pants and store-bought reproduction Hang Ten shirts, stuck in that purgatory between creating my own fashion from resale finds and wearing a uniform. Because I’d only started growing it sophomore year, my hair wasn’t long enough to be cool—and all our favorite bands and hardcore beach rats had hair down their backs. I looked like a cool kid in incubation—a pupae. This girl seemed the real deal. She lived so close to the beach she could actually grow bored with it, even reject the surf culture that I fetishized back home. She didn’t have to vacation here. She had to tolerate it. I had a lot to learn. She was a year younger than us, but her ideas were far more sophisticated than mine. That made me want to know her even more.

Like most people my age, I’d lived on fast food during the last four years, particularly on burgers. The Stuft Surfer Café stood a few houses down on the boardwalk, on 15th street. Serving breakfast and lunch since 1963, this tiny old school diner had a counter that ran along the front window, facing the boardwalk, and it felt like I imagined the wholesome 1950s felt. Their sourdough burger was greasy and delicious, a high quality, homemade version of the fast food I ate. So I literally ate a sourdough cheeseburger there every day. Jamie said she was vegetarian. A vegetarian? I was curious what that entailed.

The high school vegetarians I knew in Phoenix literally had Burger King workers make them Whoppers without the meat. Cheap iceberg lettuce, mealy tomato, and a bun—that seemed like more than torture that vegetarianism, like one of those orgasms that fizzles right as it begins. It also seemed misguided. Wasn’t nutrition more than removing the meat from things? Bread and lettuce sandwiches couldn’t sustain you, but that’s how unsophisticated vegetarianism was for many people in the early-90s. We had so few easily available products that we resorted to extremes. Jamie had a more complex understanding of the intersection of human health and social responsibility, and she lived in California, the creator of culture and trends, always ahead of the curve, so she had options. At 18, I didn’t even know the term “social responsibility.”

One afternoon, Jamie joined me at the diner counter while I ate my daily burger. She didn’t snarl. She didn’t say ‘yuck’ or deride me for all the cows that died to sustain teenagers like me. She did tease me in her quiet way about how these burgers were filling my arteries with mud, and I teased her back, probably saying some cliched easy jokes about how she couldn’t live on lettuce and tofu alone—even though I had literally never seen tofu. Smirking, she studied me like she’d heard it all before.

She’d already met our dumb jokes with better jokes and deflected our comments with lacerating responses:

Oooooh, my friends would say, are you eating a tofu sandwich covered with twigs and dirt today?

She’d fire back: No, are you eating your cow corpses in stinky ashtray sauce?

When she and I would come back to the house, they’d say: Ooooh, Aaron and Jamie sure went for a long walk!

No, she’d say, it was just a regular walk.

Despite my meat-fueled bravado, I was curious about what vegetarianism did for her, physically and philosophically. I was a dumbass, but I wasn’t stupid. She explained the dietary and environmental reasons she abstained from meat and name-brand, mass-produced stuff. Killing animals, inhumane living conditions, sick bovines pumped with antibiotics, never mind the way industrial meat production wasted water and polluted the landscape. Worst of all, industrial food polluted the human body. Okay, I said, even if it did, why did I care? I polluted my body every week with weed and beer. Couldn’t I enjoy my food, too?

Back then I still lived by the 1980s nihilistic skateboarding motto “Skate and destroy.” That idea appealed to loud, aggressive boys. Chaos was power. Destroying property was a battle we privileged kids could win, because without true social causes or actual oppression to contend with, we created causes by battling mall security guards over the malls’ “No Skateboarding.” Self-destruction was performance. It seemed cool to court death, but only because I was young enough to avoid actually dying, and cops wouldn’t shoot white kids like me for flipping them off while skating away from the scene. Drug overdoses and heart attacks lay a few years off, but they were coming. At that age, we could get drunk, eat garbage, and wake up to do it again. I was too young to see the real harm that lifestyle caused. Cumulative damage took years. I clung to my wanton behavior, as if being careless was the same as being free. I confused wildness with coolness. This posturing was part of my experimenting with identities to find the one that fit, but I didn’t yet factor in personality or actual artistic accomplishments with authentic coolness until I met someone genuinely cool like Jamie. Just eating this burger in front of this girl was my way of enacting rebellion: Fuck my life. I’m too cool to care. But as the band Cake sang that very year in small clubs in Sacramento: “Excess ain’t rebellion / You’re drinking what they’re selling / Your self-destruction doesn’t hurt them.” Boys with my dumb attitude were a dime-a-dozen. Jamie must have recognized genuine curiosity beneath my blowhard responses, because we kept hanging out.

How many days did we spend together: Two? Three? It’s amazing how much life teenagers can lead in a few hours.

She asked if I knew about all the other delicious things there were to eat besides meat. Like what? Noodles and curry, she said. Burgers made from vegetables, she said. Cheese made from non-dairy ingredients. Tofutti Cuties vanilla ice cream. No, I didn’t know about those things. She said I could pile Gardenburger, A1 Sauce, mustard, and sauerkraut on golden grilled bread like The Stuft Surfer’s bread, except without the butter. When I asked what she liked to eat, she listed tofu, veggie sandwiches, bean burritos, lentil soup, Tofutti Imitation Cream Cheese smeared on bagels, fruit smoothies, something called humus, and another thing I’d never heard of: tempeh. She even ate—dare I say it—salads. I never ate salads. Salads were obligations. Adults ate salads like they went to work.

“So you eat like a hippie,” I said.

I’d used that phrase countless times. This time it fell flat.

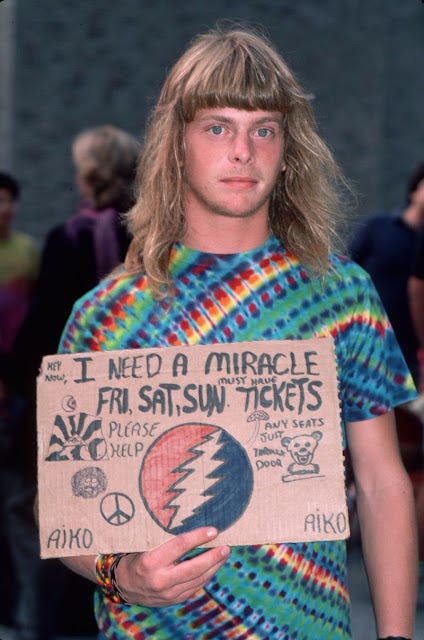

As a textbook ’90s alternative rock kid, I was supposed to hate hippies. Our ’90s indie culture rejected Baby Boomer’s flower power crap. Instead of seeing the 1960s as an era as a musical explosion and cultural awakening, I saw outdated iconography like “Mr. Tambourine Man,” saw dudes riding unicycles while wearing top hats in Haight-Ashbury, and saw images of wiggling, whirling dervish Woodstock attendees with faces painted with paisleys, and I thought that was old people’s stuff. We were right now. So the cool kids thought hippies sucked.

Jamie’s looked defied hippie convention. Jamie didn’t wear tie dye. She didn’t jam Grateful Dead. She dressed like the girls at the first two Lollapaloozas, which means she dressed like me, except cooler. The music we early-90s kids listened to at that time got labeled “alternative music,” because marketing forces hadn’t completely converted it into mainstream pop music by 1993. But what was alternative about the rest of me, like my food? My rock ‘n’ roll partying friends and I thought of ourselves as these subversive kids, rebelling against mainstream America and the many traps in thinking and behavior that adults set for us. To me, my music, clothes, and skateboarding all reflected my dedication to creating a different kind of life than the brainwashed, materialistic, 9-5 bondage that America sold you into, so basically the same things 1960s kids thought about themselves, which I only recognized later. But the point is, we rejected mainstream America, but look at what I ate: Wendy’s, Taco Bell, this industrial cow sandwich. Suddenly my sourdough burger seemed like groupthink. It was as mass produced as the mall rat culture and Stone Temple Pilots I rejected. The pepperoni on my pizza, the ground beef in my microwaveable burrito, all the stuff I ate without thinking? Poison. And worse: mainstream. Mainstream was worth than death. Jamie opened the doors of perception so I could see our world more clearly. She was LSD. Somewhere I’d heard that the singer of the very lysergic band The Flaming Lips didn’t take drugs. He advised people to “be a drug.” Jamie was. I felt so common. Her dietary choices were truly the cooler alternative to conventional American habits. Hey adults, remember: Never underestimate a high schooler.

In a college philosophy class, I eventually learned something called modus ponens logic. Applied to Jamie: Jamie was badass. She ate hippie food. If Jamie was badass and ate hippie food, then being hippie was badass.

Maybe some hippie things weren’t so bad?

To educate me, she took me to a local grocer called Mother’s the next day. The big stucco-sided store was part of a small southern California chain of natural grocers, with a large location not far down the street from us, so we borrowed her mom’s car and drove there, just the two of us.

She led me through the aisles: honey-sweetened cereals with unfamiliar logos; powdered tofu scramble seasoning and veggie burger mixes; a refrigerator filled with bottled juices and brands of drinks I didn’t recognize; unusual tropical fruit in the produce section. My crew had literally stopped at a Del Taco on the California border to celebrate our in arrival in California. Mother’s was a revelation.

America’s original natural foods industry began as a small, renegade marketplace that subverted the dominant, profit-driven paradigm and its slick advertising to cater to consumers who wanted purer food. Committed visionaries built companies like Erewhon Natural Foods (founded in 1966), Cascadian Farm (1972), and Bob’s Red Mill (1978)—people who might have described their original business model as “people not profit” and described themselves the way WhiteWave Foods founder Steve Demos described his younger self in Joe Dobrow’s book Natural Prophets: as an “idealistic hippie out to change the world.”

My mom was into her health. In the late 1970s and early-80s, Mom took me to the kind of small health food stores that had names like One Life and Food for Thought. They catered to people known as “health nuts.” In the age of the Moosewood Cookbook and Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet, healthy eating frequently meant eating buckwheat groats and cottage cheese loaf. Health food was more pragmatic than indulgent. You ate ice cream for pleasure. You ate wheat germ for vitamins, and, however naively, you felt good about yourself. Granola was a huge thing. That’s why people in the ’90s called anything vaguely hippie-ish ‘granola.’ Dude, she’s so granola. As a kid with my mom amid the bulk muesli dispensers and hand-packed bags of carob chips sealed with twist-ties, I would eat Tiger’s Milk protein bars and drink cans of Kern’s Strawberry Nectar, as if they were something other than sugary stand-ins for the usual crap. Mom ate the real health food.

The industry evolved over time, and health food became more sophisticated. But in the early ’90s, you still couldn’t find good imitation bacon. People were still sautéing whole Portobello mushrooms and grilling them as hamburgers. Vegetarians made meaty breakfast gravy from shitakes and nutritional yeast. We didn’t have Field Roast. We didn’t have Soyrizo™. Early-90s, veggie life felt like one big Gardenburger® covered with alfalfa sprouts. Before health food went mainstream and upscale, product labels were often sloppy, the fonts unattractive, either too busy or too businesslike, printed atop excessive white space or swirly, tie-dye type backdrops belonging to an aesthetic you could call “People Doodling on Cardboard at Grateful Dead Shows.” Appearances didn’t seem to matter. What mattered was the food, in this case, soy and wheat protein shaped into a Chik’n patty inside a can. Exceptions existed. Cascadian Farms had attractive packaging, but overall, the natural foods marketplace was only beginning to show signs of its mainstream sophistication. (Tofutti Cuties and Vegenaise® still show no sign of that, and I love them for it.) Prepared and frozen foods occupied a sort of “nuts for this and seeds of that” marketing style, with brands playing on consumer desire to make informed, ethical purchases by incorporating the word ‘rainforest’ into their packaging yet limiting their ingredients to largely familiar items.

There was Alta Dena dairy yogurt and Nancy’s soy yogurt but no coconut yogurt. There were tofu dogs but no Tofurky. Boxes of Fantastic Foods tofu scrambler seasoning mix and jars of Joyva Tahini were kitchen staples, but Annie’s hadn’t yet imagined boxes of gluten-free mac ‘n cheese. Even the name of the natural grocery chain Sprouts reflected the innocence of the era. But this was also the start of an era of innovation, when brands rapidly diversified to capitalize on increasing consumer interest in the health food sector, and eventually carried health food across the cultural blood-brain barrier from hippies and outdoor types who received Land’s End catalogs, to the cool kids and urbanites—an exciting time to eat what some of my friends called “twigs and berries.”

Thankfully, things have changed.

The Kellogg Company eventually bought the Kashi cereal company in 2000, and General Mills bought the independent company Annie’s for $820 million dollars in 2014. There were numerous soymilks in the early-90s, but between 2013 and 2014, almond milk saw $738 million in sales, and in 2013, retail plant-based beverage sales reached approximately $1.4 billion in the U.S. Nowadays you can get milk from flax, cashews, sesame, hemp, coconut, chia, hazelnut, quinoa, and walnut. It’s an incredible time. Avoiding over-sweetened, processed brands rarely requires effort. You can buy cashew cream pot de crème at mainstream grocers! You can find soy creamer at the convenience store! They make Soynog, faux bologna, and garbanzo-based breakfast cereal!

Turns out, a group of yoga practitioners founded Mother’s in 1978 with a 2,500-square-foot store in Costa Mesa. They expanded to seven stores around southern California locations. “At the time, it was one of the only large-scale health and natural food stores operating in Orange County,” wrote the Orange County Register. “While first catering to vegetarians, the market has since grown its shoppers to include those seeking organic, preservative-free and non-genetically modified foods. It has seven locations in Orange County. In 2010, the flagship Mother’s Market closed and relocated to a larger location in Costa Mesa.”

Since those days, the organic and natural foods industry has grown into an $88 billion dollar business that often resembles the corporate culture that it professes to subvert. Back when Jamie took me into her world, natural foods were like underground music had been: Something of an exclusive club, where you had to know someone to get you in. No matter how high the ceiling was at Mother’s and how slick the endcap displays, inside it, I felt like I’d entered a secret club.

Standing side-by-side at the deli cold case, Jamie told me to reach in and grab a pack of tempeh. I didn’t know what tempeh looked like. She pointed. Her request was a challenge and a tease, and she was savoring the act of nudging me from my comfort zone.

She bought us a veggie sandwich, a wheatgrass shot, some sugar-free soda, and some soymilk to drink, and we sat on the trunk of her mom’s parked car, eating in the parking lot. Sharing food is an act of love: sustaining another person’s body by giving up the fuel that could sustain you. Sharing food is also intimate. As a kid, trading bites felt like kissing—touching things to our lips that the other person then touched to their lips without ever touching each other. We passed the sandwich back and forth and sipped the same straw. I was on a car in southern California with a smart rebel girl—things like this didn’t happen to me.

The food was delicious: savory, salty, complex, and satisfying without the heft of animal fats. The sprouts didn’t taste as much like dirt as I expected. In fact, the combination of veggies, vegan cheese, and humus was delicious, and the sprouts were a highlight. It surprised me how much I loved their crunch.

The soymilk was richer and creamier than I imaged bean-milk could be. How did they make this from beans, anyway? Jamie shrugged. “Magic?”

To prepare my palate for the semi-fermented soy, she’d waited for me to taste the soymilk. Then she peeled open the plastic tempeh package and handed me the lump. I was confused: Tempeh is fermented? Like sauerkraut?

Not like sauerkraut, she explained. “It’s just beans. You like beans, right?”

Bean and cheese burritos were one of my favorite things. I stared at her: “Just eat it?”

Yes, she said, just a little nibble.

A little nibble. I blush thinking it.

To my relief, the flavor wasn’t gross. The texture wasn’t weird. It was different but accessible. In fact, I liked it. Right there on that trunk was the beginning of my life making my own soymilk at home and eating tofu in Kyoto and feeding my daughter tiny boxes of imported black sesame soymilk and fukamushi sencha tea.

The wheatgrass was too intense for me—it literally tasted like dirt and grass—so she drank it, but I’ll never forget how Jamie gifted me her reserved smile for trying it. “That’s more than most people,” she said.

Like many teenagers, I could see the appeal of food that challenged people. As alternative modes of living, these foods were a form rebellion: a rejection of mainstream, name-brand American life, a challenge to adults who kept feeding us crap, a way of fighting small-minded boys who wanted to reduce girls like Jamie to a pretty face, a way for nerds with brains to rebel constructively. This was also a chance at autonomy, a way for young adults to take some control over the shape of their life: We decide what goes in our body. I immediately liked the rebel spirit of ’90s natural foods, even though I didn’t like the hippie-looking packaging.

Despite my genuine curiosity, part of me was trying to impress her. If she lived in Arizona, I would try to hang out with her every waking minute of my life. I wanted her to see me as open, and brave, and not close-minded. There on the trunk of her mom’s car, she seemed to recognize that, beneath my gentle banter, I was learning. She was just so cool to me. By trying to appear open and brave, I momentarily became open and brave, but just a little. Being truly open-minded would require great effort and years of labor, rewiring my closed mind and ideas about hippies and what made cool people cool. But she started the process, she and the incredible accident of meeting her.

Maybe I imagined the attraction. Maybe I wanted the electricity there so much that I conjured it, when she was just turning another teenager on to healthy living—a teenager whose increasing drug intake clearly demanded it. It’s easy to confuse companionship for attraction, especially at that age.

But she was right: Healthy foods could taste great. She introduced permanent, exciting new dimensions to my palate: grassy, beany, earthy, pungent, and chlorophyll green.

Jamie’s friendship was fortuitous. That summer, my dad’s youngest brother, Mike, had a pacemaker installed after a heart attack put him on permanent disability. A huge heart attack had taken his mother’s life when I was six months old, and my dad had started suffering his own heart problems and issues that turned out to be diabetes. Shortly after we returned home from this Newport Beach trip, my mom’s dad would suffer a catastrophic heart attack that he would never recover from. Jamie’s ideas about food connected my family’s health problems with my family’s dietary choices, making it clear that we weren’t simply victims of circumstance. Jamie knew that we could choose to eat things that strengthened our bodies instead of eroded them. Through dietary decisions, we determined our fate. Why choose self-destruction? Because it seemed punk rock? My uncle and dad and grandparents were me, she was saying, and she drew a line from their fate to my daily sourdough burger.

That was heavy.

But what about those hippie associations?

Whether in Arizona or California, a vintage VW bus would pull up someplace, and if it wasn’t one of those cool, refurbished 1960s surfer ones that made my friends and I go Oooooh, it was a 1970s or ’80s camper van with dirty Deadheads inside, which made us go Ugh.

In 1993, my favorite bands were loud. Bad Brains thrashed. Soundgarden stomped. The guitars on Smashing Pumpkins’ Gish wailed. The Grateful Dead jammed. I didn’t jam, but I mostly hated the Dead because of the hippies I associated with them. Interestingly, the Meat Puppets had already snuck the Dead into my musical diet by covering songs like “Franklin’s Tower,” “Scarlett Begonia,” and “I Know You Rider,” dressed as acid-punk, before I knew they were Dead songs. In high school when I loathed Bob Dylan and his ’60s ilk, the Chili Peppers had already turned me on to Bob Dylan by transforming the folky “Subterranean Homesick Blues” into a digestible punk-funk song. My ideas about ’60s things were loosening, but Jamie tossed the first bucket of acid that dissolved my idea of “hippie things,” which led to me dismantling my unfounded, reflexive hatred of things that were softer, quieter, healthy, flowery, and not overtly punk rock. Behind every successful man is a strong, visionary woman. Isn’t it always a woman? Or as Bob Dylan sang in “Just Like a Woman”: “I was hungry and it was your world.”

Man, did I miss the point about the ’60s.

One night toward the end of my stay in Newport, Jamie and I stayed up all night talking. I don’t remember how it happened, or if she was leaving Newport or I was, but we’d somehow both cleared our schedules in order to spend time together. My friends did something else. Her friend did something else. The world shrunk to a single stretch of beach at a single moment, with her at the center.

We walked on the sand. We swung on some swings at the nearby playground. We ended up talking in my dark, carpeted living room, and I don’t remember a word we said. I only remember being together amid this tense, mounting sizzle of expectation that this was obviously our chance to kiss. All my friends were asleep in their rooms. Her mother slept next door. We could do whatever we wanted. We clearly both wanted this—whatever it was—but something kept me from leaning in for the kiss. I thought it was a desire to talk first and kiss later, to get to know each other more, even though vacation meant that there was no later.

Whatever we talked about—California, music, our ambitions—the midnight hours passed into unreasonable hours: 2 a.m., 3 a.m., 4 a.m. We’d committed. As attracted as I was to her, what she’d showed me of herself had opened me up further than anyone had in years, and I liked our trajectory. I told myself: You don’t stop that kind of trajectory. But the vacation timeline already had. Instead of being able to date, we only had this night. Was this the way to spend it? Just talking? Inside the quiet dark living room, we could feel what things might have been like had we lived in the same state.

She had the most kissable lips of any girl I met in high school. I thought about her all through college, wishing we went to the same school, wishing we had each other’s phone numbers, wishing we had the chance to grow together instead of shrink into tiny memories. Sometimes I stared at her face in my three photos, conjuring her back to life. There she was in 5 x 7 matte finish, smiling from behind a wall of hair in our yard. There she was, her shoes and lips that vibrant red. There was our frozen moment that night, still undecided.

With time, the sound of her voice faded from memory. I eventually forgot what it sounded like at all. I eventually forgot her name. As a college freshman, I wondered how her last year of high school had gone. The next year I wondered which college she’d decided to attend, or if college was where she thought she belonged. Did she go to the third Lollapalooza shortly after we met in Newport? I did. The bands were amazing. Was she out there in California somewhere singing The Flaming Lips’ “She Don’t Use Jelly” like I was in 1994? Was she too smart for ordinary universities and instead chose some unconventional career path? By the time she would have graduated college, her photos ended up in a box of photos I quit opening. They were images from an era I no longer revisited, stored in the closets and basements in the various houses where I lived while I built my adult life. And yet, while the details of our one night faded, I never forgot the feeling of being together, or forgot our time at that grocery store.

We could’ve “hooked up,” but I didn’t want to remember her body before everything else, even if she had wanted to spend a romantic night together as much as I did. If we couldn’t date, then I wanted to remember her the way I do now. After all, personality was the sexiest thing about another person—their spirit—no matter how physically attractive their exterior. So I did that teenage boy thing and let the night pass without making my so-called move.

At some point the sky outside the living room curtains lightened, and our moment had passed. I felt disappointed. She seemed to, too. Her poise had softened. In the dim blue morning, she seemed shy, vulnerable and young again, not the influential giant. Did I not find her attractive enough? Was something wrong? I loved her face more than my high school self could articulate but I had made my choice, from fear, from respect, from confusion and naïveté. We fumbled our goodbyes, her moving toward the front door, out my front gate, and into the adjacent yard as the sun began to rise.

When my Arizona friends and I left the beach for home, Jamie and I didn’t exchange phone numbers or mailing addresses. Maybe we felt embarrassed or shy? Maybe we accepted that these days were destined to be our only ones and that our lives would always be lived in hindsight. Maybe I’d hurt her feelings or let her down by not kissing her. Hesitant coy boys can be very unattractive. Cell phones didn’t exist. Social media didn’t exist. So we said goodbye, and back in Arizona, I developed the one roll of film that I took on that trip.

By May 1994, the year after Newport, I wrote seemingly enlightened things in my college notebooks like: “When you go to a place to eat, you should know exactly what is in that food.” That was Jamie’s voice right there. I went so deep into good-food-land that I sketched an idea for an all-natural “fastish food” restaurant chain that took Mother’s food to the masses the way McDonald’s took crap to it. According to my notes, the menu would contain “hormone-free meat, organic vegetables” and offer “an outside eating area—nice view of the sky, nice view of the scenery outside.” Because time outdoors was as important to human health as food, right? I sure wish I’d built that restaurant chain in 1994 and made some money. I was ahead of my time—thanks to Jamie.

The following year in college, I took science classes that led me to read more about the environmental and moral dimensions to industrial agriculture and animal slaughter. I never abandoned unhealthy food during and after college. I was a regular at tacos joints and devoted bean burrito eater, but I did quit fast food, and I found restaurants near my university campus that sold heath food. During the second half of my college freshman year, I took my first trip to the Gentle Strength Co-op in Tempe, Arizona. It stood a few short blocks from the university art department, where I took art classes in a haze of marijuana smoke, with Flaming Lips cassettes playing on my Walkman.

Although I didn’t know what a co-op was, I’d seen this particular market from the record store across the street. It occupied a non-descript concrete box, ringed with greenery and attached to a small parking lot. Lots of beat-up VW busses parked in there. I loved old VWs, so I noticed. With the business’ high patio walls and some playful vegetation painted on the exterior, it looked like a tiny green oasis in Tempe’s scorching world of hot asphalt. I never thought to go inside. Whatever that place was, it was a hippie place. I belonged on the other side of the street, buying rolling papers at the headshop and surf music at the record store, and eating at the Mexican grilled chicken joint. This stretch of University Boulevard was a mote that divided cultures, with subversives here and hippies there. Thanks to my budding vegetarianism, I finally went into the co-op in 1994.

Past shady mesquite trees and a rickety metal gate, I entered an air-conditioned interior that reminded me of Mother’s in Costa Mesa. But where Mother’s had the marketing muscle and square footage of a well-funded chain, Gentle Strength was a small, scrappy joint partially run by volunteers. A communal board hung beside the entrance, where people stuck flyers for yoga and classes about energy alignment and dog-walkers’ business cards. Beyond that was an aisle of cosmetics that smelled of roses and witch hazel. Produce was kept in back next to a freezer case filled with soy-based ice creams, and a case filled with non-dairy products.

The place was also filled with hippies.

When I’d think things like Dirty hippies! after meeting Jamie, I’d always think: Why am I saying this? Cursing hippies made me feel bad. My disdain was a performance. Hatred wasn’t natural. When you’re young and unempowered, it feels good to have someone beneath you in the pecking order, be it younger classmen or a different subculture: Goths were freaks, hippies were stupid, we were the cool ones. Hating hippies was my ego-booster. Like a sugar high, the effect didn’t last. Instead, I felt worse. I played the part, but it wasn’t me. Those subcultural barriers weren’t either. Why should I dismiss an entire group of people, especially fellow freaks? My friends and I said it ourselves about ourselves: How could anyone generalize about an entire group of people because we skate and have longhair and earrings? I listened to a lot of Flaming Lips in those days, and it was like what Lips’ singer Wayne Coyne said about narrow musical thinking: “We don’t care, the music rocks.’ We liked it. And I always thought, well, how weird! I mean, how can people who like music say, ‘This is the friend and this is the enemy?’” He saw no meaning in stylistic divisions between David Bowie and Black Flag and Pink Floyd. “To me, it’s all music,” Coyne said. “I don’t care where it comes from.” Just because I had numerous annoying encounters with rambling cosmic hippies didn’t mean I should dismiss them all as stupid. That defied my own hope that other people would respect me no matter how I looked. I wanted a place as a freak in a straight world. Why couldn’t I extend the same generosity of spirit to unshowered hairy people in flowing tapestries who liked the Dead? I thought about inclusion before we knew the word. Enforcing divisions felt wrong to me reflexively—on a molecular level—like it went again nature. It certainly went against the true nature of punk, which was to free yourself of social constraints and be your true self. Embracing rebellion and individuality, not mean-spiritedness, was the true cool thing.

LSD emerged in the 1960s, but somehow it wasn’t a hippie thing to me, and the LSD my friends and I started taking helped dissolve barriers because it rewired your brain. Old ideas changed. Old hatreds softened. Love surged through you—good vibes, cosmic connections, visions of interconnectedness. Suddenly rainbows and happy faces appealed a bit more. Iconography I rejected looked attractive. The old skulls and monsters of my teenage skateboards looked too aggressive. You tripped and let things in. You took acid because you wanted it to change you, and you imitated cool people because they could change you, too.

“Hippie eventually was a name that people didn’t want to be called, because it was a way of packaging them up and dismissing them,” Jackson Browne said in the 2020 Laurel Canyon documentary. “But a hippie was, like, a young person just burgeoning or just opening, just blossoming—somebody who’s getting hip. I mean, it was a way of living your life out in the open, being a freak and being unapologetic about who you were.”

Unfortunately, the co-op café’s menu was spartan. I remember vegetarian sandwiches with crunchy cold sprouts hanging from the sides, and this plate of mixed steamed veggies piled on brown rice. The dish seemed unfinished, like the chef had forgotten to add sauce. What I read in Vegetarian Times magazine suggested I needed food that could heal the damage I did by all my partying. And with my minimal cooking skills, I could replicate this boring ass veggie plate and those sprout sandwiches at home.

On the flipside, the co-op is the first place I tasted a mango, a good red pear, and a really good peach. And inside the co-op, I learned to judge less. I never became one of them, but I did become one with them. Beneath their dreads and tie dye, I saw their own rebel spirit, a crunchy kind of granola punk ethos that led them to this countercultural place and unconventional lifestyle. However we dressed, however we spoke, we all here to subvert the dominant paradigm, because mainstream America was sick and dumb. I mean, Bad Brains would always sound better than the Grateful Dead, but that was surface level stuff. Deep down, we were all one. And that wasn’t the psychedelics talking.

Despite our different aesthetics, couldn’t we just love all people, man? That was the most hippie thing to say, and yet, it felt natural. It was me. Saying the phrase love all people actually filled me with joy. My tense muscles loosened. My angry inner teen smiled. It made me—dare I say it?—happier. Was there something neurological happening? Did the very idea of universal love release oxytocin and serotonin? Had the hippies discovered Nature’s greatest sober drug? Philosophically, trying to love more and hate less was the right thing to do, and I didn’t have to dress like a hippie to practice that.

Once my narrow mind got pried open, new ideas about identity and intelligent rebellion took root, which allowed me, over years of effort, to become a kinder, more understanding human being, one who appreciates the way others feel about themselves when they actually find themselves and dress however they want, one who takes joy in seeing other people enjoying being who they are and gives them room to be that free, a person who wants to see you as you are and meet you there—even help you get there.

The fact is, as an adult, you don’t need to belong to a group. You become your own group. You can be a mélange.

Thanks to Jamie, I still eat natural foods, drink bitingly green plant juices, and shop at natural grocers here in Portland, Oregon—but the food’s way better. Maybe I would’ve had the same epiphany from another friend, but I didn’t. I had it with her. My wife grew up eating vegetarian food, and her enduring commitment to health reinforces my own. We also both love the nostalgic flavor of what we call “90s vegetarian food,” which comes from the classic combination of Bragg Liquid Aminos and nutritional yeast. Co-ops take me back, and that comforts me. In fact, my daughter and I went to our local co-op twice this week. “This store has the best honey,” my daughter told the co-op clerk. “Do you know Rescue Riders? There’s a dragon on that show called Melodia. She’s a songwing dragon.” The next time we visited, the clerk greeted my daughter with “Hi, Dragon Girl!” She’s so in love with certain bright, sparkly imagery that she names her animal toys things like “Rainbow Flower Sparkle Wing” and “Pink Star Shine”—a child’s innocent, inborn psychedelia. My wife and I have intentionally introduced her to a range of flavors and textures since infancy, including seaweed, seafood, and green tea. We hope it sticks. You never know what will, but when they do, they do.

In our mid-forties, whoever Jamie is, she is as she always will be: a smart, influential, progressive force of nature whose fierce playful presence lays in every bite of healthy food I take, every trip to the co-op I make, every jug of soymilk I make with my daughter at home, every salad I choose over a burger, every moment I think of those cows in pens on huge industrial farms, mooing to escape, whether she knows her influence or not—and of course it’s not. Why would she? I was some dork from a few days in her past. Surely men threw themselves at her in college. It’s easy to imagine her as a successful environmental lawyer in Costa Mesa. I’m a middle-aged skater who loves an Impossible Burger as much as a grass-fed beef burger. Sometimes I even think of her while I eat a real burger like I did this past summer during Portland’s annual Burger Week. I picture her cherubic face staring at me over The Stuft Surfer counter, not shaking her head, just there, my fleeting friend whose presence outlasted our time together by an entire lifetime, her eyes smiling forever, and her skin as clear as her conscious, because before she ever graduated high school, she already knew that a person could be bigger, smarter, and more responsible than even the dreamiest, most ambitious teenagers imagined we could be.

Great piece, Aaron. There were several Jamies in my life as well, goth-ish alterna-girls that everyone fell in love with and that most guys could never really talk to. You did better than most. If you've never read the "Hippie Food" book Jonathan Kauffman wrote a few years back, I highly recommend it. I went through several feints at eating nothing but health food store food in the early 90s myself, and it really was sprouts/granola/portobello mushroom burgers and not a whole lot else. These healthy kids today don't know how good they've got it.

Now go out there and find out what happened to Jamie!