The Mermen

This San Francisco instrumental band's cosmic jams were powerful enough to heal my twenty-something soul right when I needed them

Winding up the side of the 9,157-foot tall Santa Catalina Mountains outside of Tucson, the two-lane road entered a deep wooded canyon too high for the morning sun to penetrate. Every time I drove it, I knew I’d entered some strange, special period of my life.

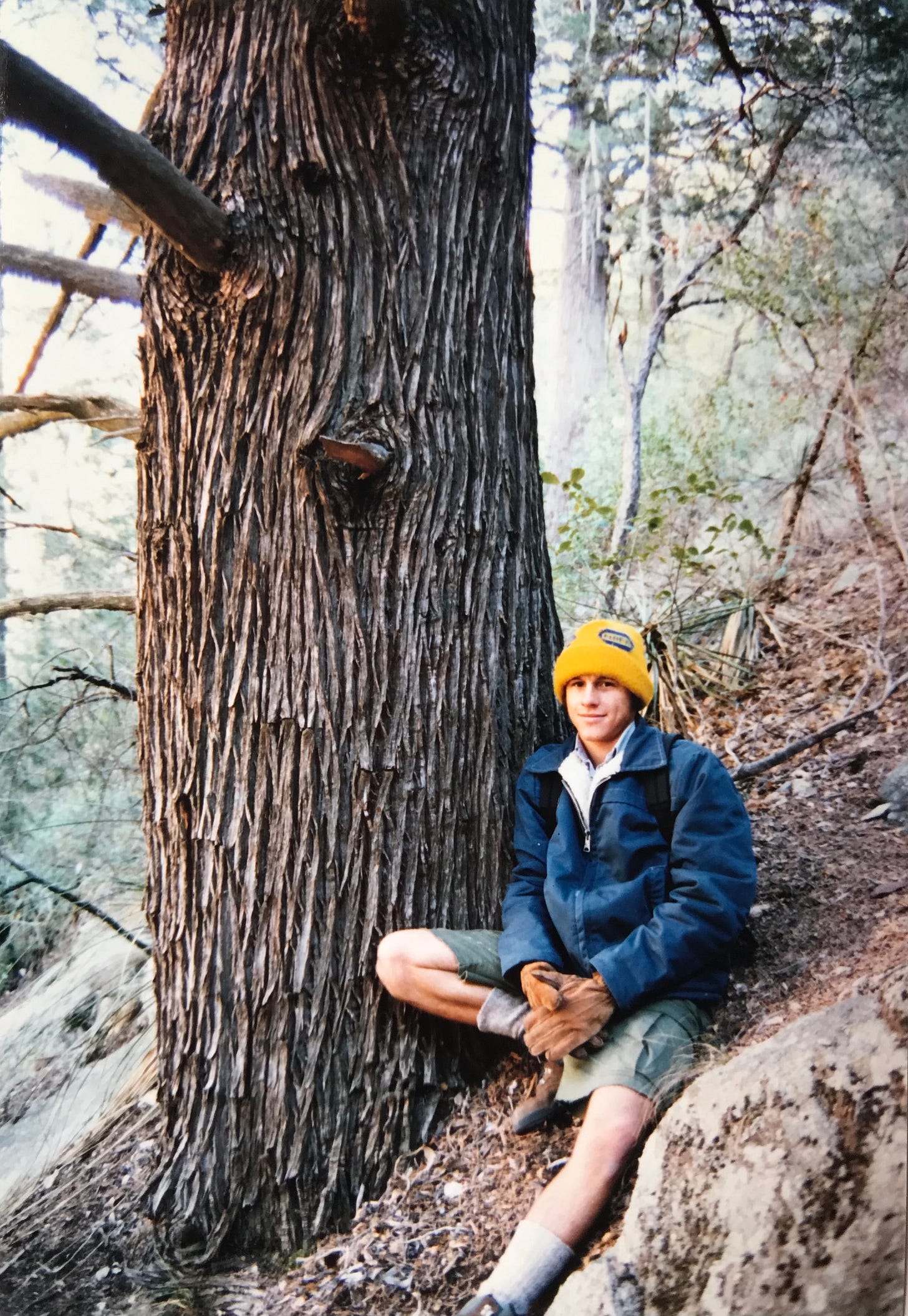

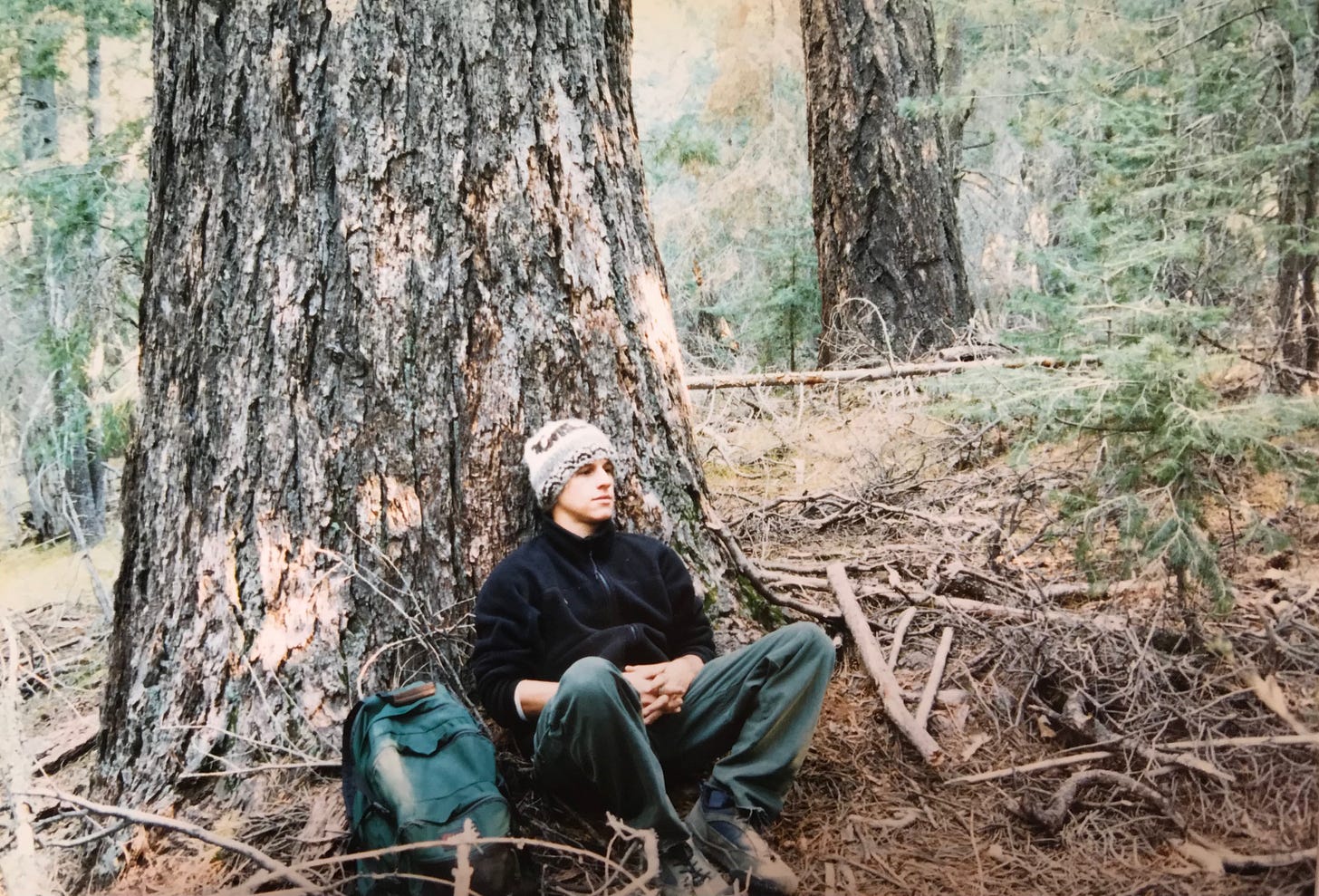

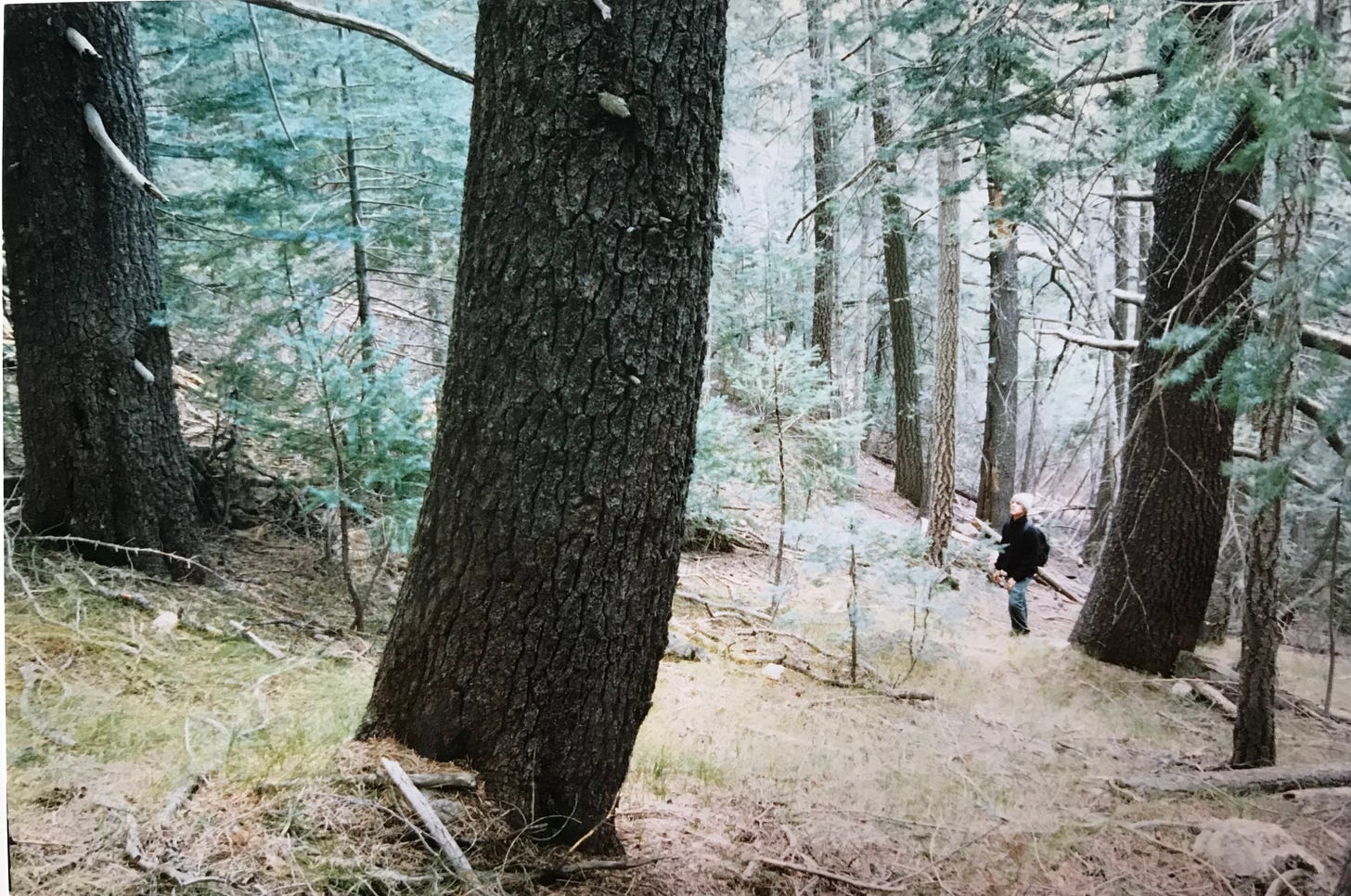

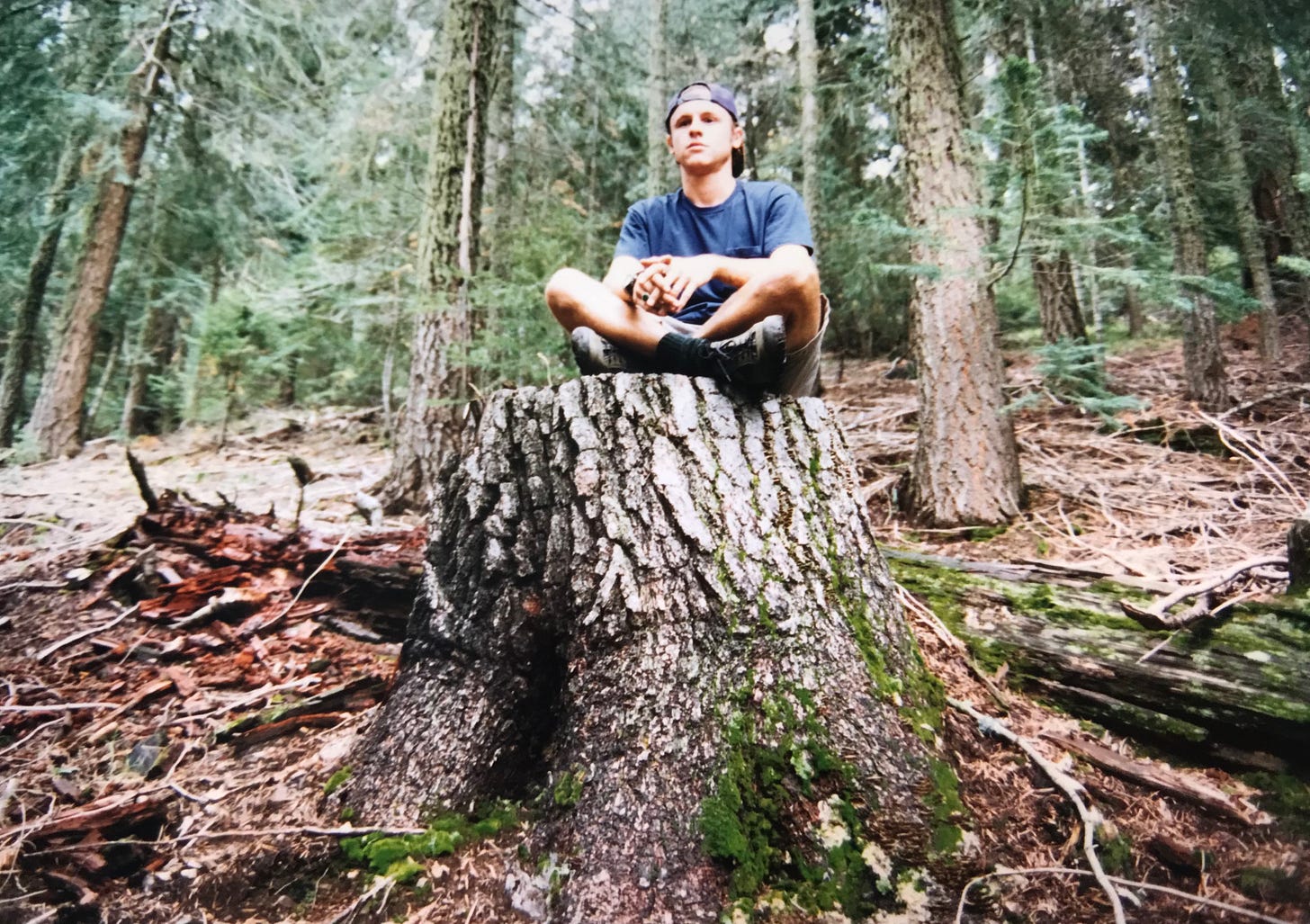

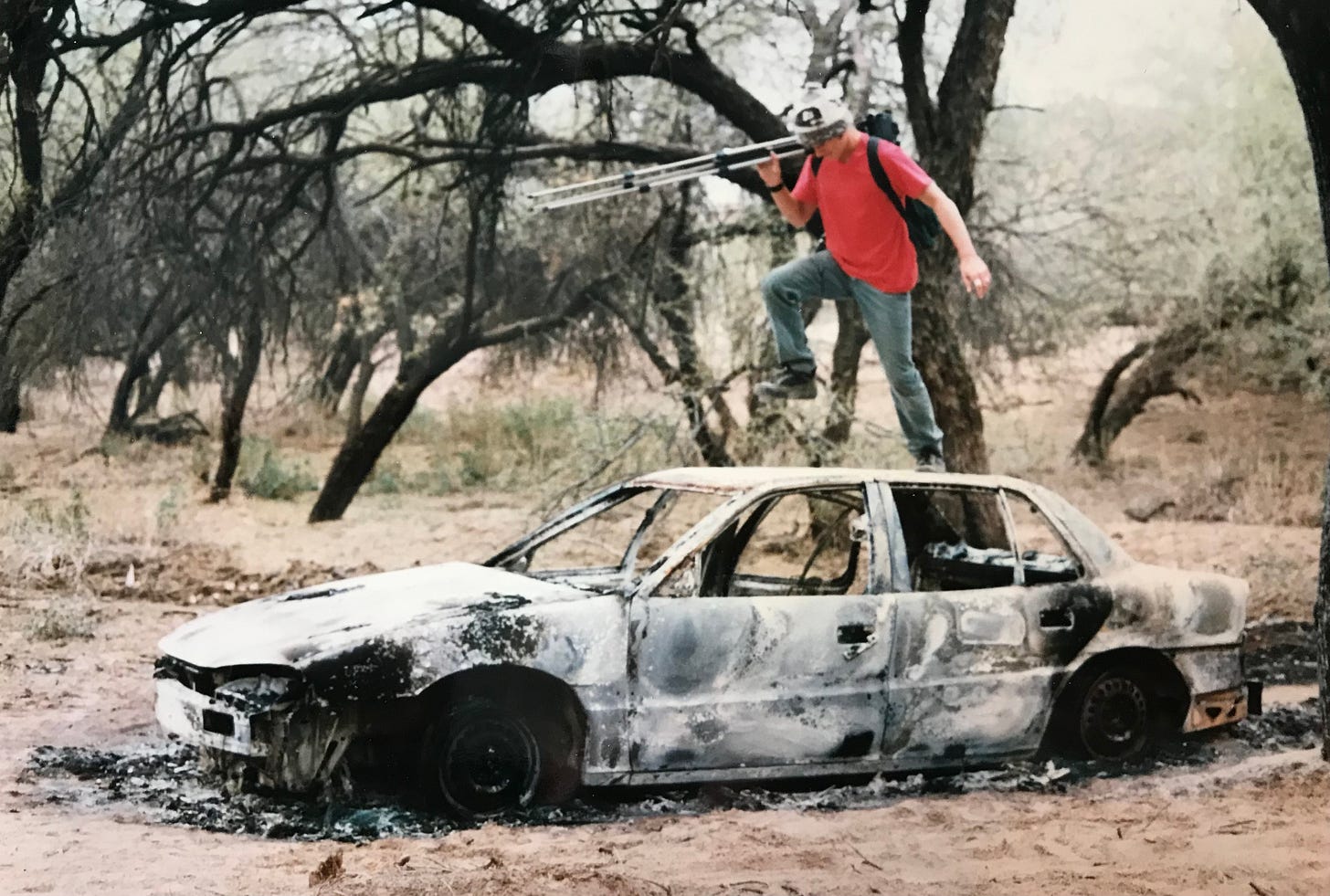

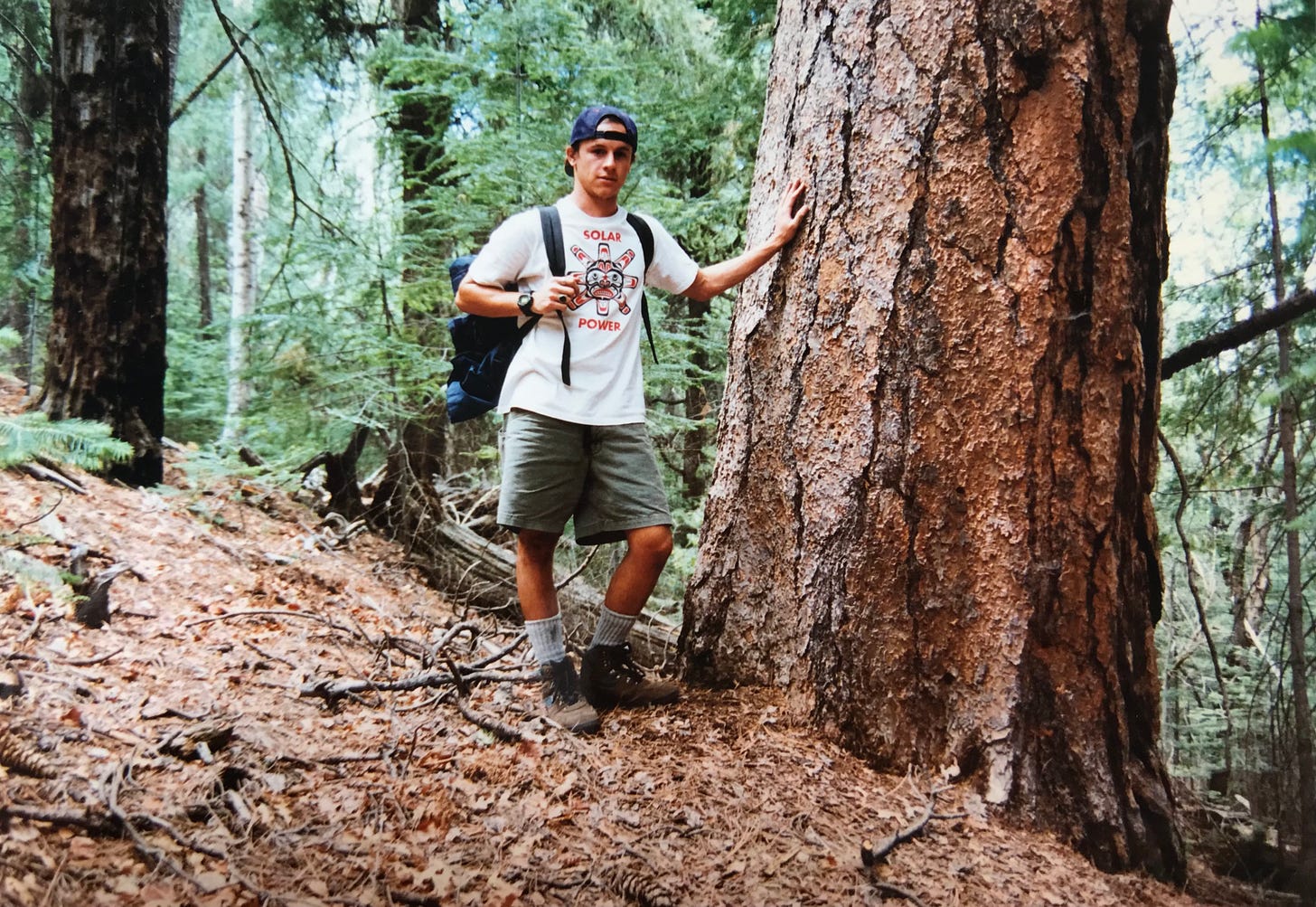

At 20 years old, I was looking for something. I didn’t know what. I just knew that the wilds of my native Arizona pulled with such force that, for all of 1996 and ’97, I went hiking off-trail in places like Upper Bear Canyon and Marshall Gulch two or three times a week, tromping between old-growth ponderosas and enormous Arizona Cypress trees along a trickling stream when I should have been attending college classes. On these solitary wilderness excursions, the Mermen’s instrumental surf album Live at the Haunted House was my constant companion. Blaring from my small Toyota truck’s speakers, slow songs like “Lonely Road” and “Pull of the Moon” amplified the serene, meditative mood that Nature’s grandeur set.

I discovered the psychedelic instrumental trio in a Tempe record store in 1995. During the early ’90s, instrumental surf music experienced a revival. Bands like the Trashwomen, the Bomboras, the Surf Trio, and Man Or Astro-Man played inventive modernized versions of the instro tunes that bands like the Ventures and Lively Ones played in the 1960s, so indie record stores created their own surf sections. When Pulp Fiction’s 1994 soundtrack catapulted surf music to greater fame, it sent me searching my local stores for similarly bombastic music. Instead of the bombast, the slow songs moved me most.

For me, surf music provided a welcome break from all the thunderous, boot-stomping sludge that my friends and I listened to during the so-called Grunge era. Mudhoney and early Soundgarden were rad. But the slow surf stuff could sound psychedelic, trance-like, even mystical, in a way loud rock couldn’t, and I craved mystical. After three straight years of bong-smoking and beer-drinking, I’d entered a meditative phase. Instead of time with friends, I craved time alone. I had always been many things: solitary and social, artistic and idiotic, crass and caring, sensitive and selfish, contemplative and demanding. Now I was also lost.

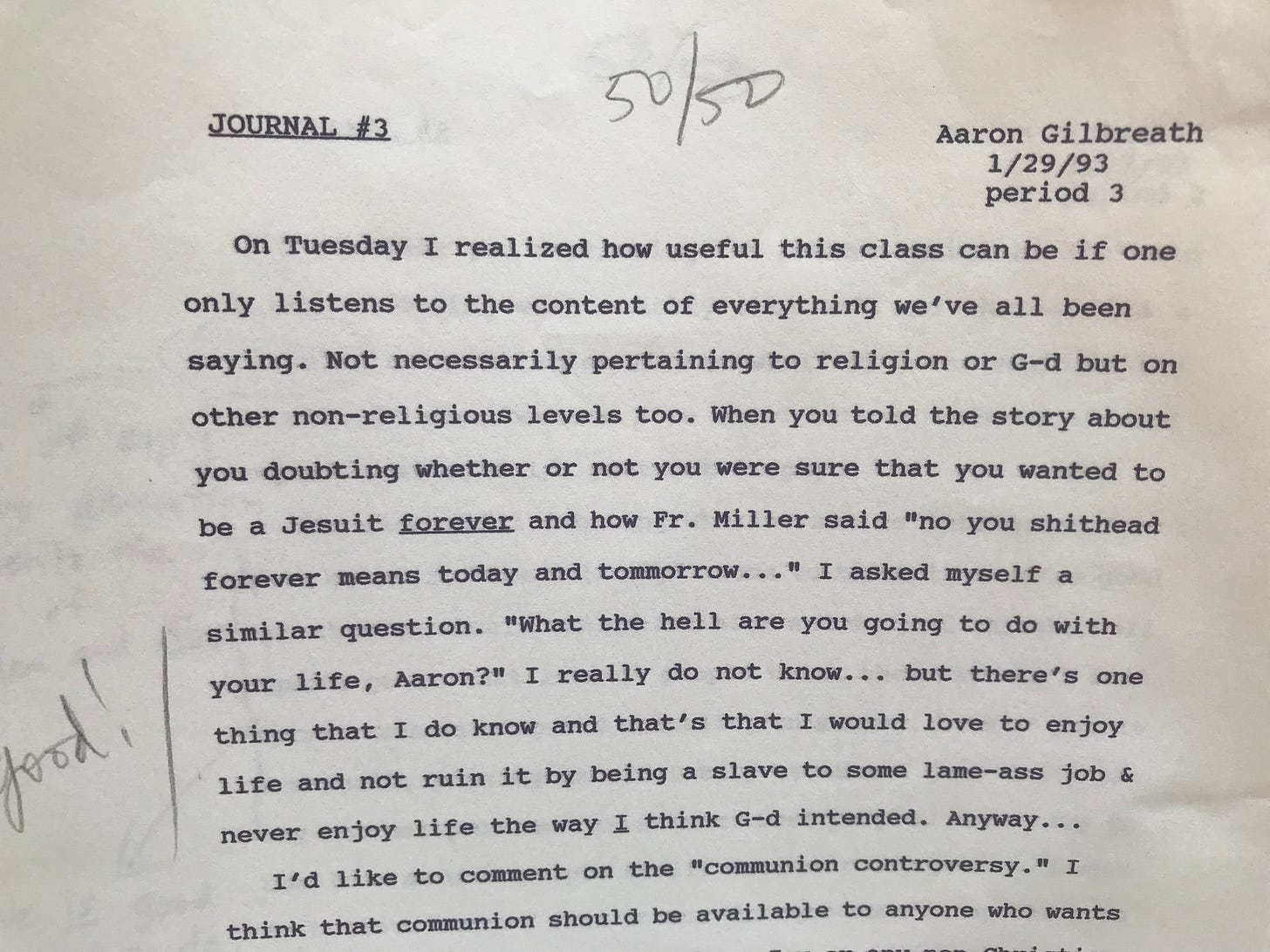

At some point everyone has to reckon with their future. I wondered about my future when I was a senior in high school. My English teacher had students keep a weekly journal, reflecting on readings, class discussions, and life, and I journaled about where I was headed.

I went to a Jesuit high school. We talked God a lot, even though I was Jewish and didn’t consistently believe in anything more than a vaguer spirituality. But high school’s still a buffer from the future. College is different.

Many kids reckon with themselves in college. When you have to pick a major, you have to ask yourself what you want to do with the rest of your life. Deciding your future career requires deciding what you like in general, who you are, and what job you could stand doing every waking day till you die. In college I liked a lot of things: drawing, ecology, rock ‘n’ roll, art history, literature, photography. I also liked getting high too much. After choosing a drawing major just to have a major, I kept wrestling with the larger questions: What is my real major? Who am I? Who do I want to be? Everything was clouded by weed, beer, and the LSD he occasionally dropped and the coke we sometimes snorted.

When I finally accepted that my daily weed habit was out of control, I surprised everyone, including myself, and announced that I was moving from Phoenix to Tucson. I told everyone I was moving because the university in Tucson offered the state’s only bachelor’s degree in ecology. But more than anything, I was moving to get away from drugs—not just weed, but my inability to steer clear of all the hard stuff we’d started tinkering with—which required getting away from my friends and this addictive side of myself. I moved to start over and to build up my other sides: the intellectual side, the explorer side, the literary side, the ambitious side. Besides sobriety, I needed direction. I needed room to grow. Youth had me shrinking. So halfway through college, I left my best friends in Phoenix, during the heat of my surf music phase. I didn’t move down to Tucson to live in extreme solitude. I never really thought about what it’d be like to live there alone. I just did it, and I built a monkish existence because that’s what I sensed I needed. Looking back, those Tucson years are some of the oddest and most intense I’ve lived, but also the most exhilarating. It was a time of discovery, of adventure, of life lived on my own terms on the open highway, in the most charming desert city there is, before its sweeting downtown revitalization. It was also a time of self-preservation that came from deep unease.

Like the tiny wasps who laid their eggs under thick oak bark, I built a protective barrier around myself to make sure nothing but essentials got in. I’d quit drinking by age 21. I was done with bong rips. I was done with cigarettes, done with house parties, acid trips, coke-snorting, and hours spent on couches watching people play video games. The less I socialized, the less temptation I faced, and I could go about figuring out what I wanted in life. Most importantly, I could spend my time doing what interested me. At that age everything interested me—books, mountains, architecture, music, cinema, Taoism, folk art, Indigenous culture, Mexican cooking, and exploring the Mexican-American border. So did the contents of my own mind. Without weed, my mind was a universe unto itself, and I wanted to examine it. Tucson made room for all of these interests. The Mermen set the mood.

Once I bought Live at the Haunted House, it fueled my search. I learned to hum nearly every guitar lick. I knew every drum fill, and I thumbed the fluid bass lines on my knee while driving so no one could see. “Honeybomb,” “Into the West/Be My Noir,” “Pull of the Moon,” “My Black Bag”—this was the greatest stuff I’d heard since first hearing Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love and Smashing Pumpkins’ Gish in high school. What made it different was how different I was when I found it. Instead of staying up late only to sleep off hangovers the next day, I awoke with the sun to drive places where I hiked alone for hours, stepping over rocks that hid rattlesnakes, scaling lichen-encrusted cliff faces, and having hummingbirds buzz my sunburned face in fern-filled glades. Seeing the sunrise is a very different experience when you’ve actually slept through the night. The magic of wild nature intoxicated me now instead of intoxicants, and Mermen music sounded like wilderness felt: energizing, elemental, transformative, raw, and ethereal. Here in the land of wild boars and saguaro cactus, over 300 miles from the ocean, Mermen songs like “Quite Surf” and “Splashing with the Mermaid” perfectly suited my borderland adventures, because beyond the song titles about whales and kelp was a universally powerful songwriting that tapped into that deep primal something that the best music taps into.

In 1996, I rarely encountered other cars this early driving into the Santa Catalinas. Be it snow or sweltering heat, I liked to set my arm on my open window frame and smell the piñon pine pitch and sycamore trees. On foot, the air chilled my nose while the sun drew out reptiles who sunned themselves on the warm granite.

Southeastern Arizona is part of the physiographic province called the Basin and Range. Here tall mountain ranges rise up from the dry desert floor, creating a series of wooded mountain ranges separated by desert, what became known as Sky Islands after writer Natt N. Dodge’s 1943 Arizona Highways article described the Chiricahua Mountains as a “mountain island in a desert sea.” I eventually explored most of these Sky Islands: the Santa Ritas, Huachucas, Chiricahuas, Peloncillos, and, my favorite, the Pinaleños. The Pinaleños contained the state’s densest black bear population and one of the Southwest’s largest unbroken expanse of old-growth conifer forest. It was a dreamland. At first I focused my attention on the Santa Catalina Mountains.

The Catalinas were huge, and they were close. Running along the entire northern side of Tucson, their soaring parallel ridgelines formed a cinematic backdrop few cities could match. Their ecology was also unique. Starting in thick Sonoran Desert, the range’s vegetation changed dramatically with increasing elevation, so that they climbed from saguaro cactus to oak woodlands to pine-fir forests every few thousand feet. In winter, snow dusted the Catalina’s forested peaks. In spring, forbs turned their brown foothills green, often speckled with purple lupines and orange poppies. When you’d come out of a Tucson grocery store or restaurant, the range’s tips often loomed in the distance, their ever-presence reminding residents that relief from summer heat was an hour’s drive away. For a hardcore hiker like me, the Catalinas were the city’s great escape. I could spend hours in them and still get home in time to study over dinner. Geologically, they were convoluted enough that it would take years to get to know half of their hidden canyons and little twists and folds. They held a universe right at my backdoor, so I spent my time exploring them instead of studying as much as I should have in the university library. Nature became my church and library. John Muir said the Yosemite Valley “might well be called a church, for every lover of the great Creator who comes within the broad overwhelming influences of the place fails not to worship as they never did before.” Southeastern Arizona was my Yosemite. John Muir also said, “In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars.” Now my task was to understand Nature’s message.

Back then, that was my whole trip: I believed that wild places held the answers to all of humanity’s questions about cosmic meaning, death, right and wrong. I don’t remember if I read that somewhere or figured it out on my own, but with an evangelical force, I came to believe Nature contained a spiritual and moral code. I hated to use the word ‘evangelical’ since it invoked religion. Nature was not a religion in the usual sense. Sure, it became my religion, but it didn’t involve rules, rituals, or gate-keeping clergy the way organized religion did. Like God, Nature was accessible to anyone. You just had to work to unlock its meanings. That’s why I studied ecology, existential philosophy, and moral philosophy as an undergrad: I wanted to learn what the great thinkers thought about these weighty subjects, to know if others saw some objective moral code or cosmic messages embedded in the fabric of the universe, specifically in wilderness. If wilderness was the earth in its purer, largely unchanged form, designed by forces other than human activity, then whatever objective truth existed would be there to discover. Not in the Bible, not in criminal law or stone tablets—things created by mortals—but written in nature’s unaltered design. I wrote a lot of college papers about these ideas. They’re currently buried in a bin full of papers in my basement. I don’t remember the exact components of my argument beyond that general premise. I do know that I agreed with another thing John Muir said: “The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.” And I agreed with what ecologist Aldo Leopold, who read Muir, said: “No important change in ethics was ever accomplished without an internal change in our intellectual emphasis, loyalties, affections, and convictions. ...In our attempt to make conservation easy, we have made it trivial.”

Besides hiking alone, the main way I tried to discern truth from reality and build a worldview was by taking Philosophy classes.

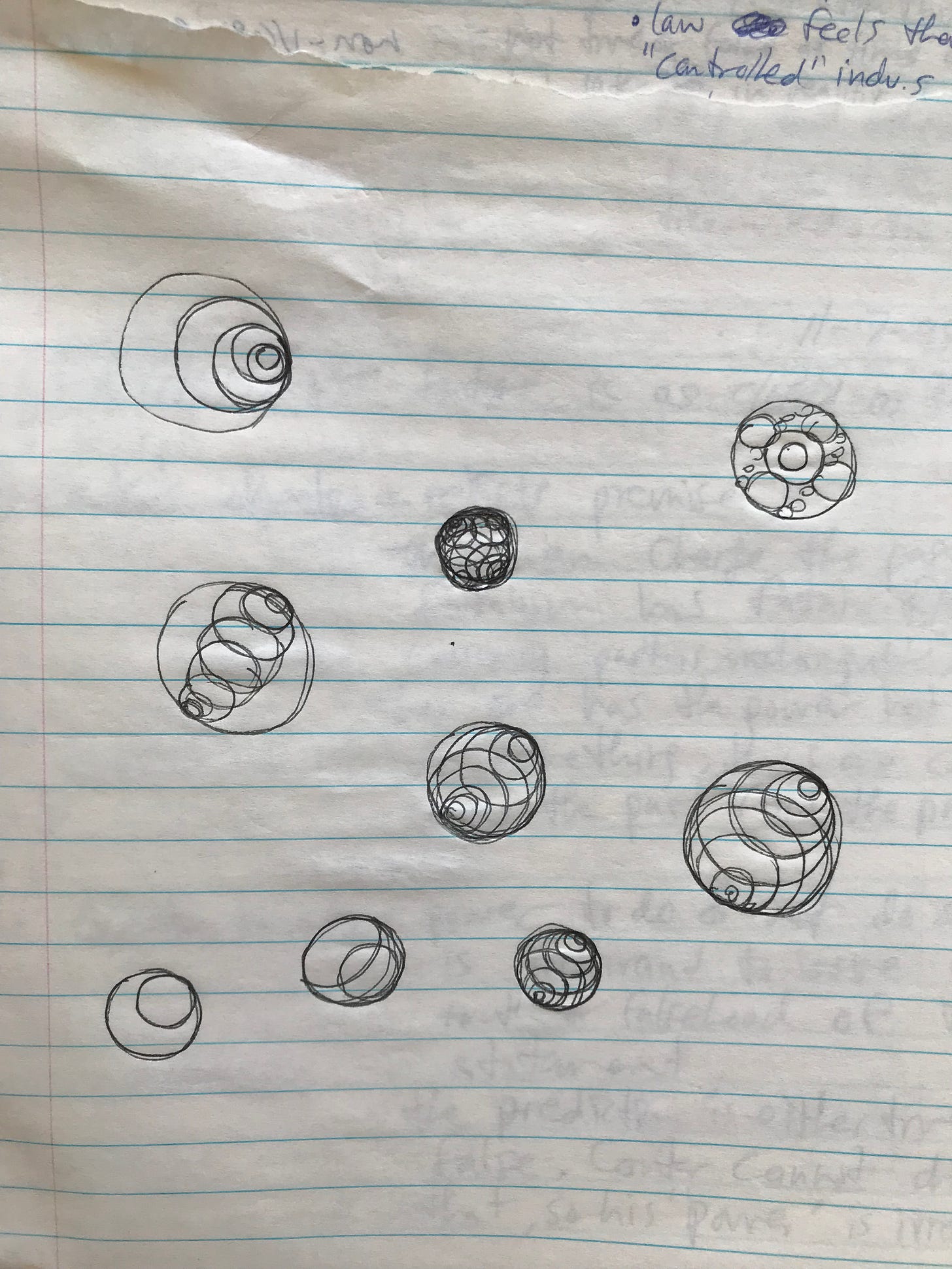

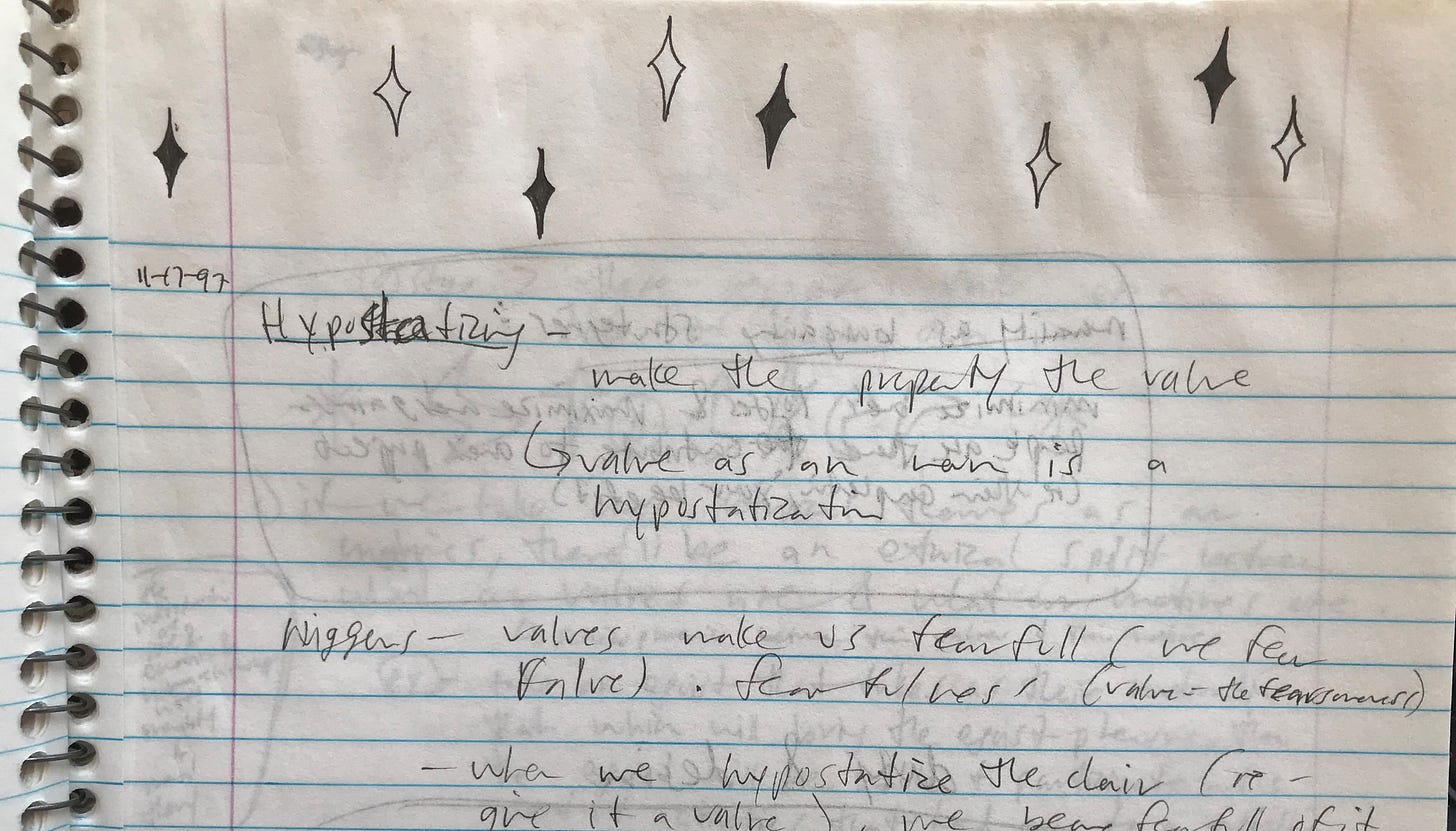

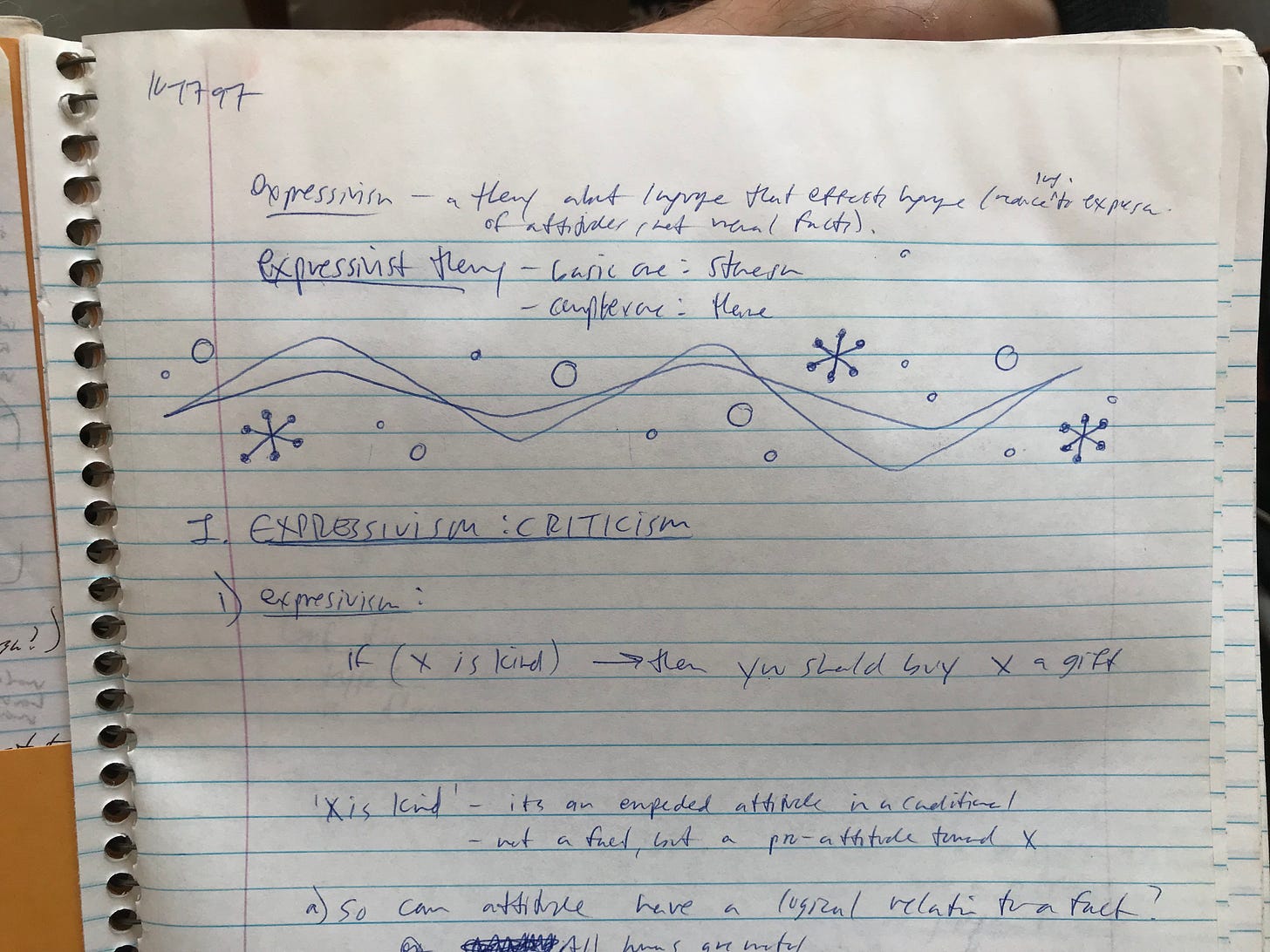

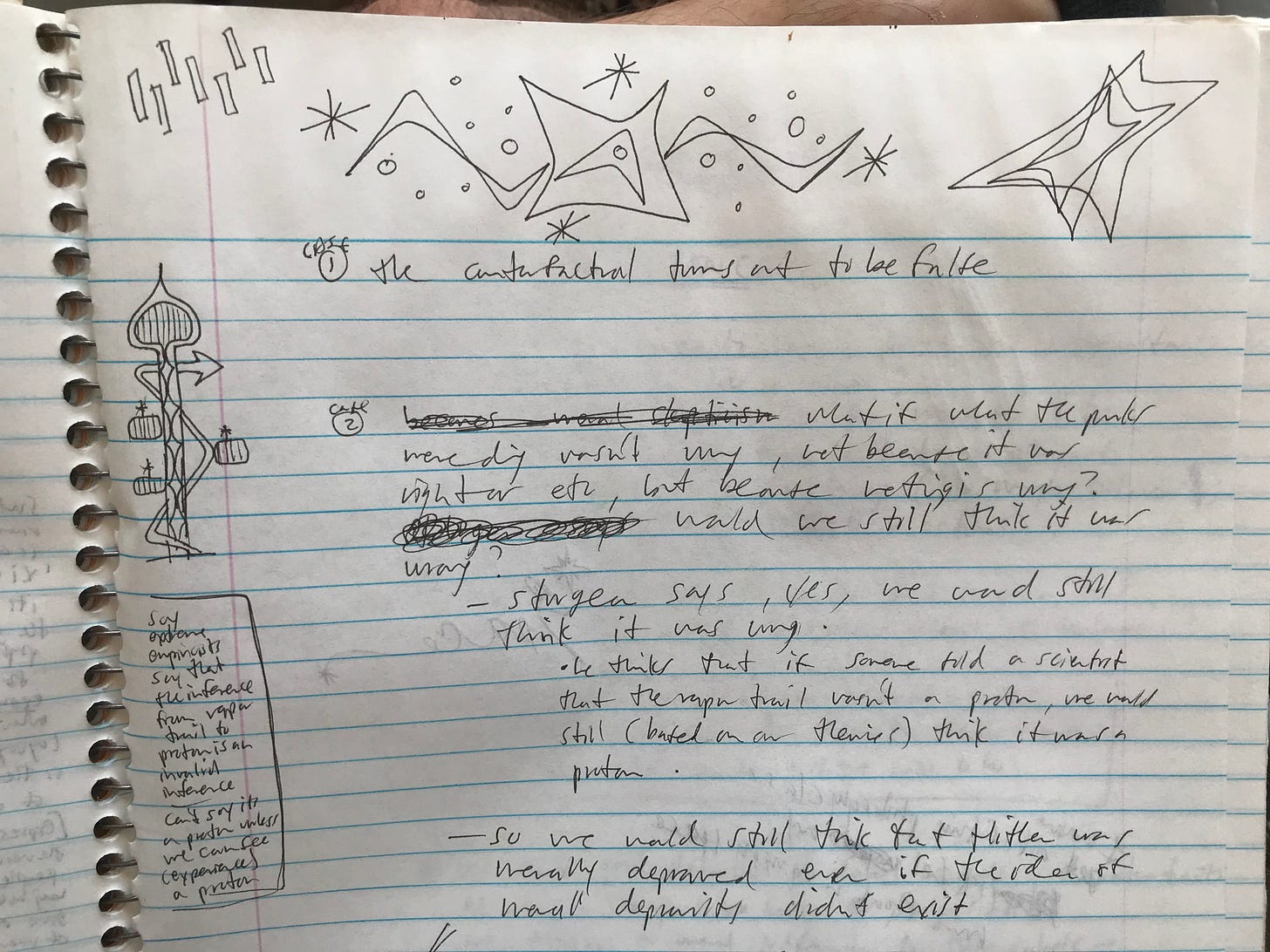

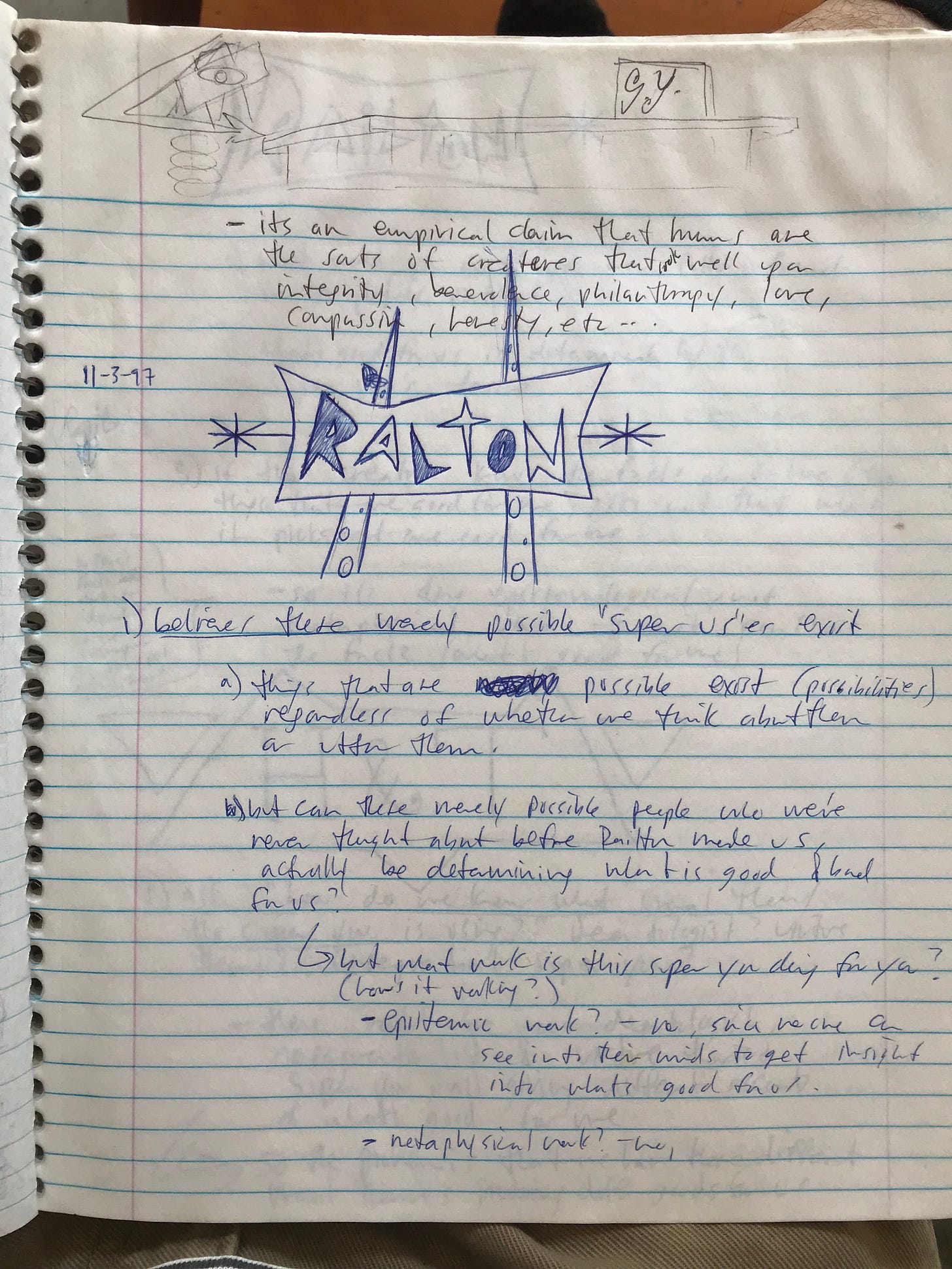

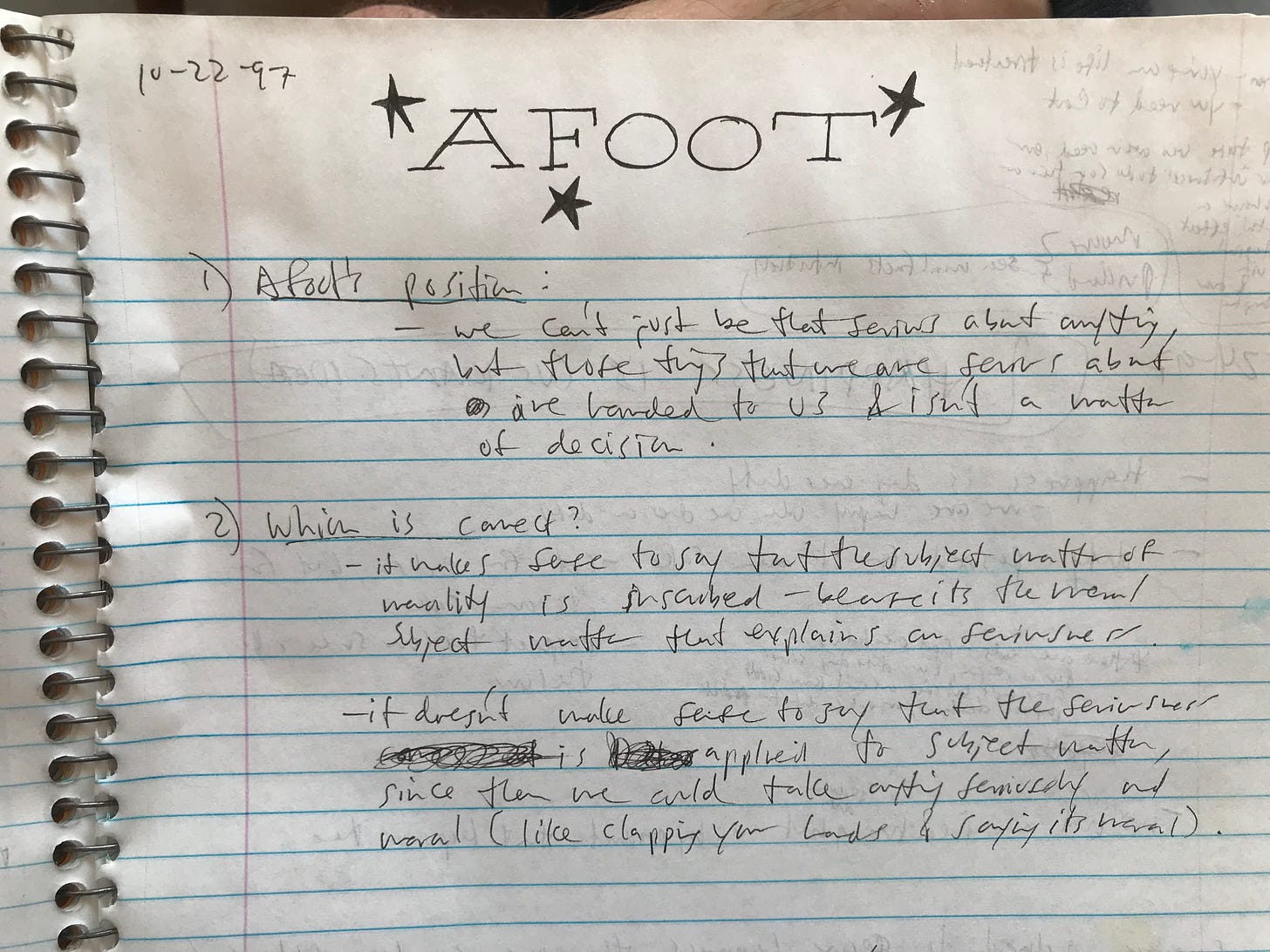

In a bin in my basement at age 46, I found a bunch of college notebooks. Between 1995 and 1997, I spent a lot of time thinking about this stuff in my college Philosophy courses. Amid all these class notes about causal determinism and Parfit’s explanation of physical connectedness and theories of personal identity, I drew psychedelic geometries influenced by my time outdoors.

It all seemed connected to me.

I also drew faces.

Along with Mother Nature, I also got deeply into mid-century vernacular architecture, particularly Googie coffee shops and ’60s design motifs and roadside signs. From my many books on Googie, I drew this stuff all the time in my notebooks, as my mind drifted from the professor’s lecture on Hegelian dialectics to things that got me excited.

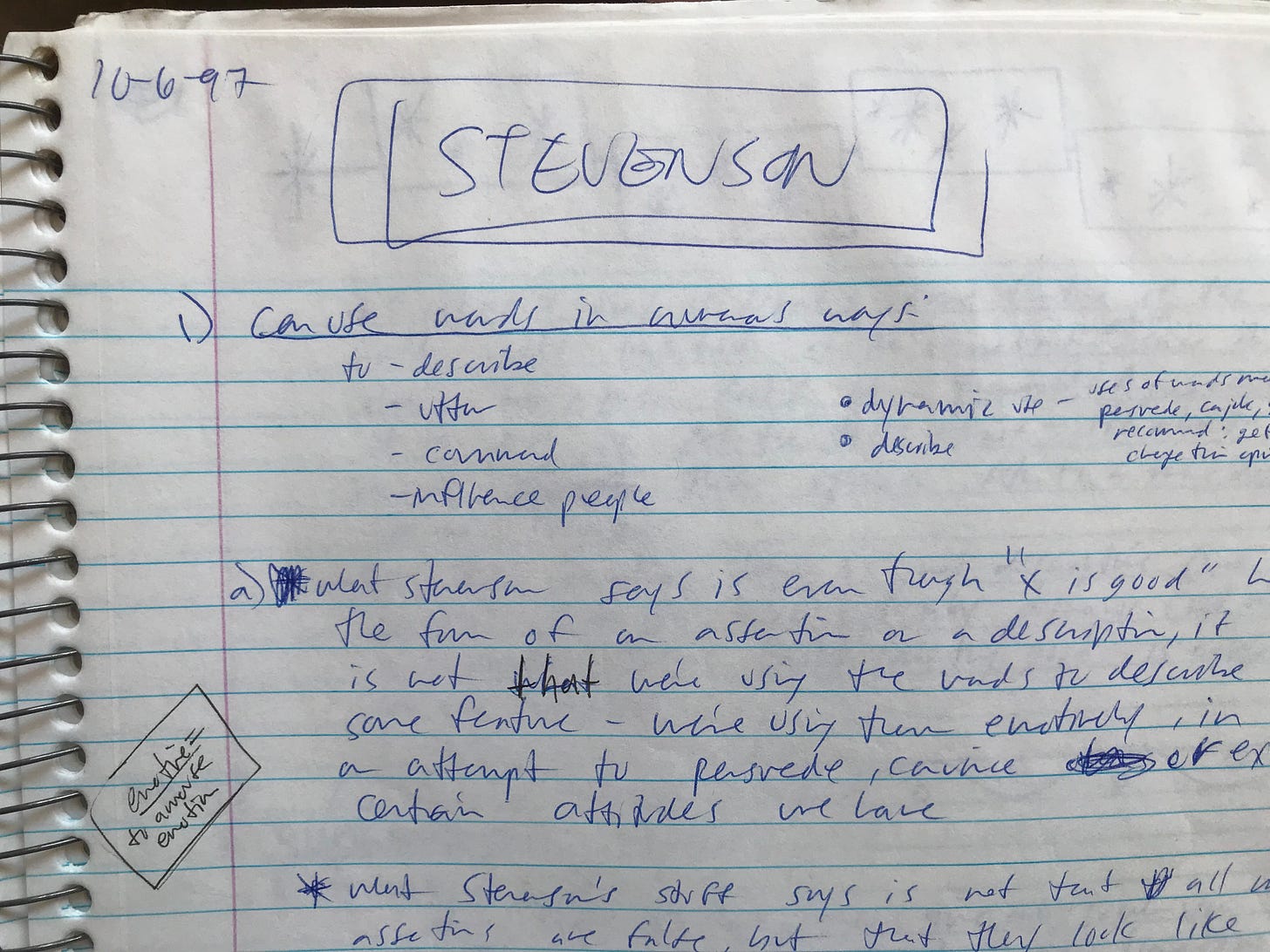

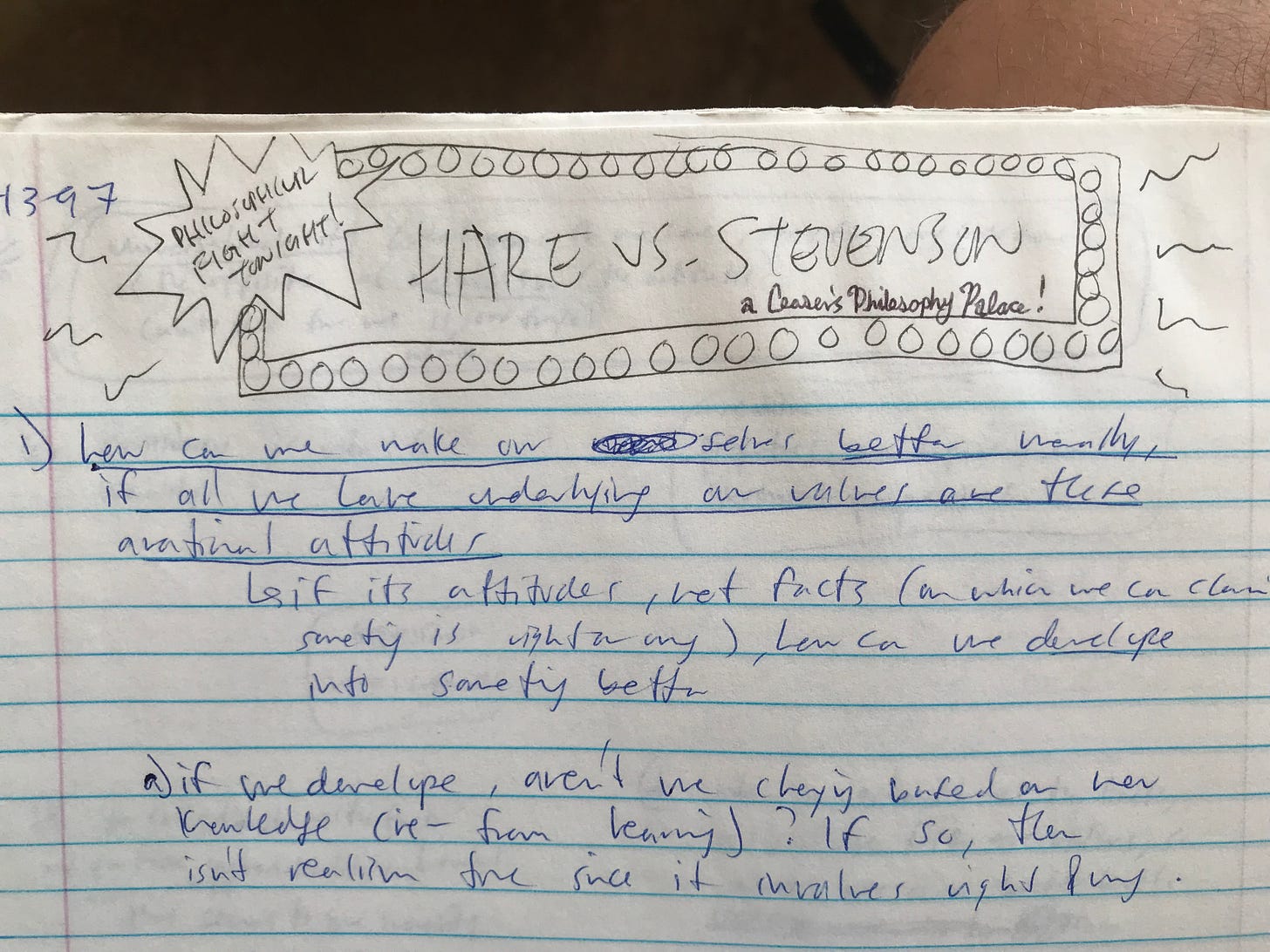

I loved discussions on the moral status of animals, but certain discussions could get so dry that I tried to make them more fun by transforming the discussion notes and philosophers’ names into Googie signs:

Maybe there was something in Googie’s geometry that appealed to my Naturalist sensibility, which primed me for the geometry I found in wilderness. Back then I was just goofing around.

Why write “Charles Leslie Stevenson” like this:

…when you could write his name like this:

Or better yet, write it as “Hare Vs Stevens. Philosophical Fight Tonight! At Caesar's Philosophy Palace!”

I don’t even remember what R.M. Hare thought. Or any of Hegel’s, Heidegger’s, or Nagel’s ideas. I only remember John Muir, Mary Austin, and Aldo Leopold, which I read outside of class, never as assignments.

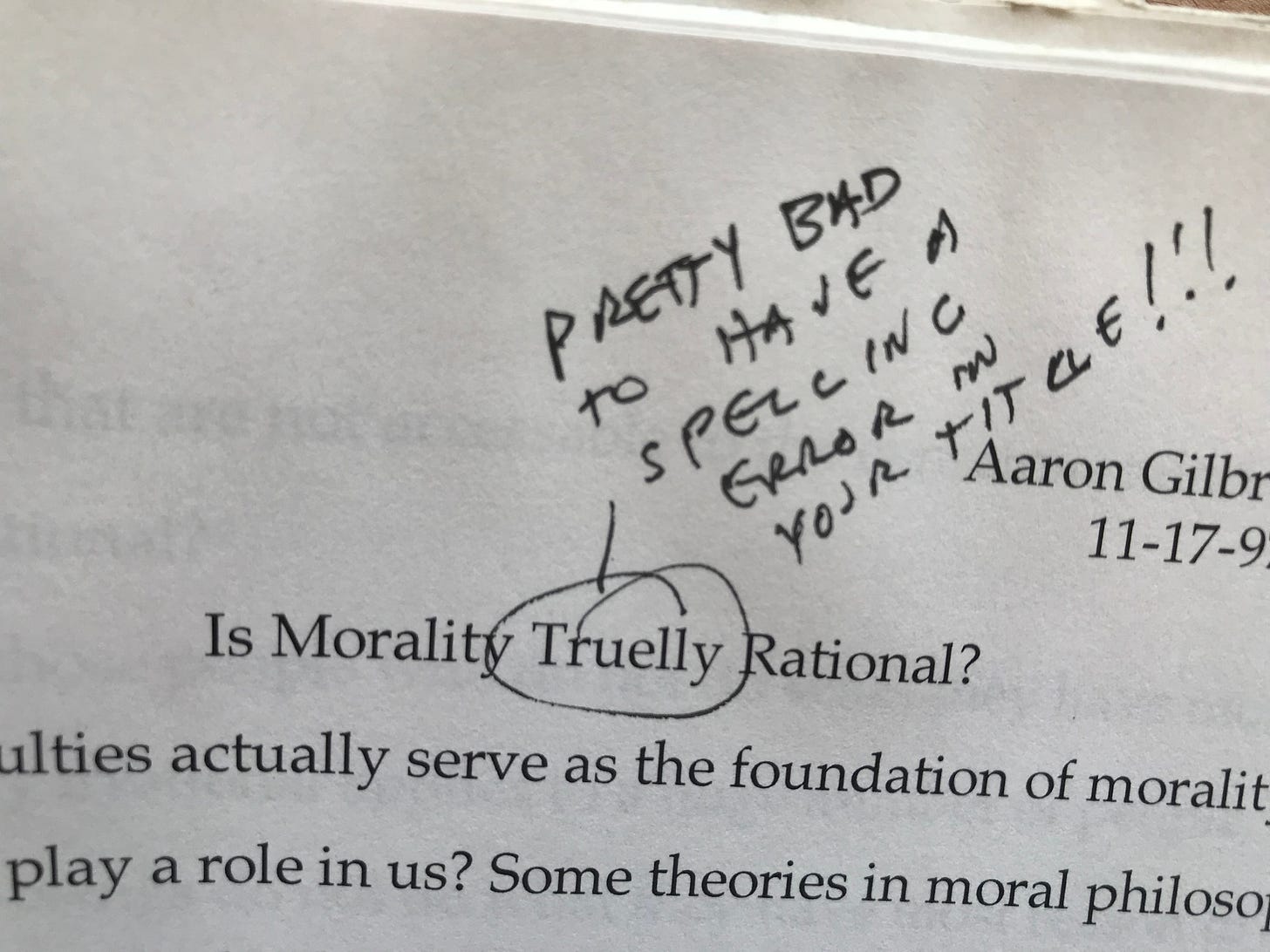

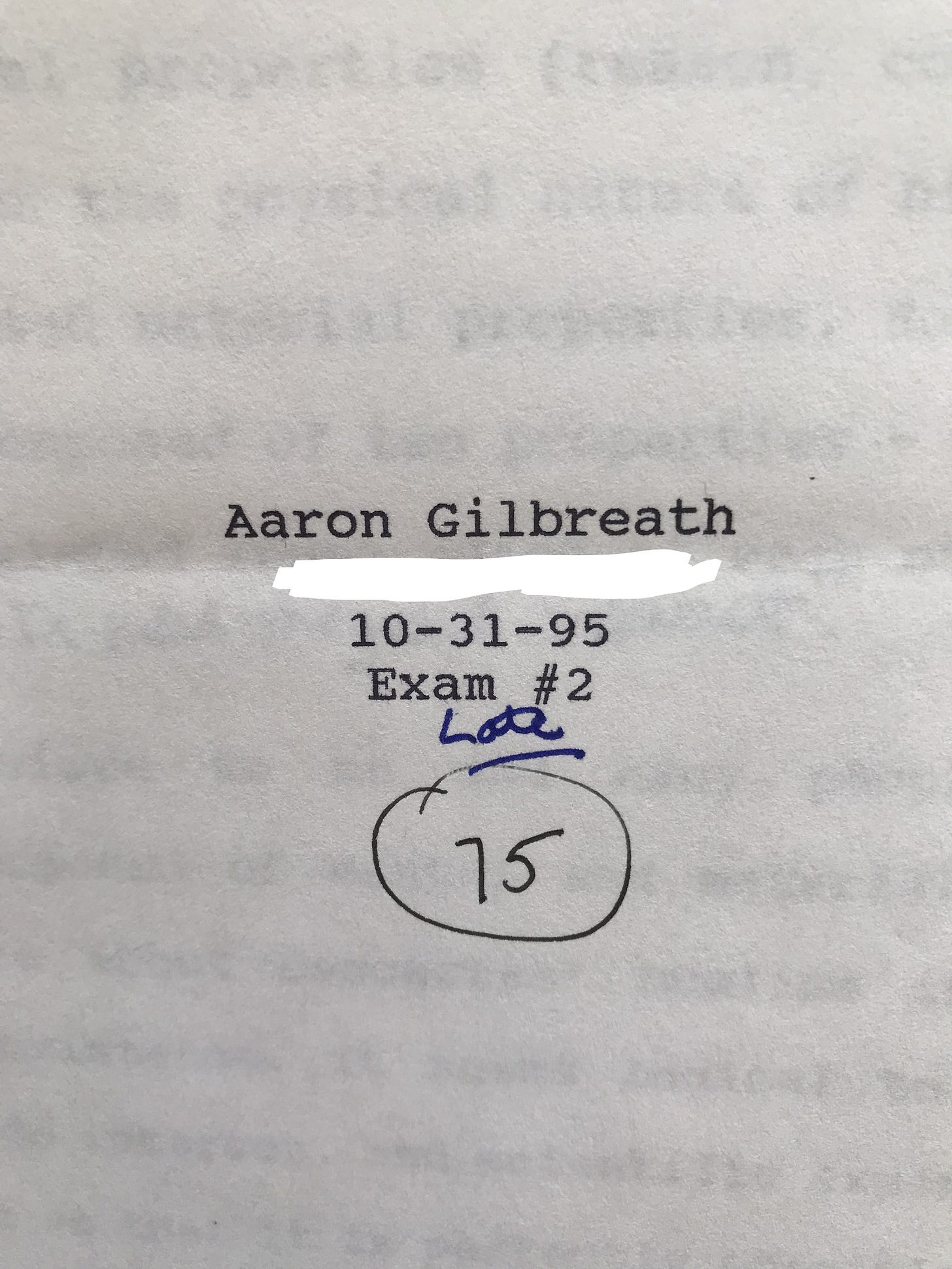

That partly explains why, no matter how much I enjoyed my Philosophy classes, I could also be sloppy and lazy and rushed. Look at the my teachers comments on my papers:

I paid more attention to the subject matter than I did to papers’ formatting or course requirements. Moral and existential philosophy were personal. I wanted to think about them. I didn’t want to invest time in formalities or structures or the rules of my classes, or even spend much time in them. I wanted to explore while jamming music.

Was it chance that the first Mermen album I grabbed from the record store turned out to be their best? Or did that album end up as my favorite because it was my first? Despite my attachments, Live at the Haunted House is objectively strong stuff. The fidelity, the track list, the band’s energy and control over their songs—everything that creates perfect albums is there.

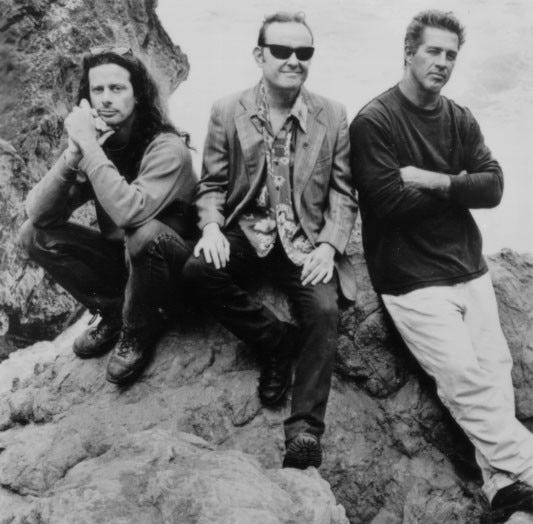

Although I didn’t know it when I discovered them in 1995, The Mermen had built a large local following in their native San Francisco.

Guitarist Jim Thomas officially founded The Mermen as a trio in 1989, adding bassist Allen Whitman and drummer Martyn Jones to form what some fans consider the band’s classic lineup. Thomas is now in his late-60s. He lived in San Francisco’s Ocean Beach neighborhood for 15 years and surfed that beach’s famous waves, which can get big. He even named one of their best songs “Ocean Beach.” After getting priced out of San Francisco in the early 2000s, he moved to Santa Cruz, where he still heads The Mermen with different members and still writes music. When he started the band as his after-work hobby, he was 35 and working in a retail San Francisco music store. The Mermen is the only band he’d ever played in.

Born in New Jersey in a Polish and Greek family, Thomas grew up in Newark near New York City, the son of an electrical engineer, but he was drawn to the ocean rather than the concrete jungle. Thomas spent 10 years doing little more than working and surfing. He went so far as briefly living out of his car to be close to the waves. “I didn’t even listen to music all that much,” he told one interviewer. “I lived by the East Coast, worked as a waiter, and I just surfed all the time!”

Thomas left New Jersey for San Francisco in 1987 with nothing more than clothes, a surfboard, and an acoustic guitar. He had no plans, only a dissatisfaction with what he’d done before. “I was basically fed up with everything I did in my life,” he told an interviewer. “I had like 30 different jobs, was 35 years old, and I was like: What am I gonna do now? I saw the ad for the job in the music store, got the job, and once I was in the store, I started writing all this music. They always had four-track recorders in there, and I’d always demo them for people and write songs as I would do it, you know? Allen, the bass player worked in the music store at that time and he always wanted to play when he heard me doing these songs. He said, ‘I like these songs, I play bass,’ and eventually he joined the Mermen, after four other bass players or so. Allen was a real pro player at that point. I just played music and wrote music but didn’t know where I was going with it, but I realized I had the ability to write music.”

In 1995, I could relate to Thomas’ situation. By age 20, I’d gotten so bored with squandering our precious time that I’d quit drinking by my 21st birthday and was searching for a way out. What was my next move? How did I want to spend my days? No one in my circle seemed as fed up as me. I didn’t surf. I didn’t play music. I read and drew and journaled, and because I hiked the Arizona backcountry so much, I drew and journaled about the Arizona backcountry. But I didn’t know what it would all add up to. I didn’t know how I could turn my interests into a career. I could only leave my hometown for a new city and try to start over. And like Thomas, I wondered: What am I gonna do now? And like Thomas, I moved.

While Thomas worked at the music store, he kept composing little original melodies while showing customers how the four-track recorders worked. Even though San Francisco was less expensive back then, it was still expensive, so he got a second full-time job baking cookies at night. “I worked all day in the music store till five o’clock,” he said, “and after that I worked in the cookie store till two o’clock in the morning! This was crazy! But making all that money made me able to buy all that musical gear and I just kept buying more gear, and now I have a full bar recording studio with a 24-track, two-inch machine, the best Pro Tools system, all great tube gear, all the best stuff.” With that money, he patiently gathered a bunch of vintage equipment while patiently writing songs.

Thomas’ guitar can fill a room, and it isn’t just the volume. He has such a wealth of effects, and ones that he combines in unique ways. His guitar has choruses, melodies with layers that sound so thick it’s like an orchestra coming out of one guitar. This is called a polyphonic effect. His lush, rich sound is clearly the sound of a musician who loves to experiment with tone. “I’m obsessed with guitar sounds and buy all these tube pre-amps,” Thomas told one interviewer. “I’m always experimenting with recording equipment, mics, speakers. All my life and money goes into this musical endeavor. I love it. I could sit here and freak up a guitar tone and listen to it forever!”

He gets that tone from a simple guitar run through a complex ecosystem of amps, pickups, and pedals. “I play a ’90s Stratocaster with two Jazzmaster pickups and a P-90 between them, strung up with set of GHS strings, gauged .013 to .060,” Thomas told Guitar Player. “The two output jacks on the guitar send the Jazzmaster pickups to the preamp of a Fender Dual Showman and the P-90 goes to a RealTube distortion box and a DOD Meatbox. …For a polyphonic effect that sounds like several guitars at once, I have a clean sound going all the time and blend in the distorted sound from the P-90 with the low-frequency distorted fuzz in parallel, plus three tremolo pedals driving different loopers. This creates a sonically huge, dramatic statement. Three stereo reverbs, with wet-dry mixes controlled by foot pedals also enhance this sensibility. The differing reverb decays multiply the guitar’s sounds from the different speakers.” I’m not a guitarist, so I barely know what most of that means, but I know the effect it had on me. His music became the soundtrack to my search for myself.

His music was instrumental, psychedelic, and had overtones of the form known as surf instrumental music—a style from the 1960s. And yet, Thomas hadn’t even heard Dick Dale, one of surf music’s founding fathers, when the band recorded their debut. By that point he only wrote music for himself and composed in a relative vacuum. The music was strong enough that he and Allen decided to record it. “A woman who worked there [at the music store] paid for the recording of our first CD,” Thomas said, “Krill Slippin’.”

After Thomas and Allen started jamming, they formed a deep musical connection that you can hear in the music. They put a small ad in a local paper, listing little more than a need for “surf bongos,” and a drummer named Martyn Jones auditioned. Professional and experimental, Jones was equally adept at both locking in tight to their grooves and stretching out on extended jams. The hobby was now officially a band.

“The first show the Mermen formally did was the night before the [1989] San Francisco earthquake,” Thomas told an interviewer. “Before that, it was kind of informal.”

Bringing a bit of the Grateful Dead’s family spirit, Mermen encouraged fans to record their shows. Fans often set professional quality microphones at different positions on stage. Others ran their gear directly through the mixing desk onto professional-sounding digital equipment. This resulted in a huge catalogue of hi-fidelity live recordings that fans share for free at places like Archive.org, and it created both a fan community and a sense of camaraderie between the fans and the band. So did the Mermen’s unwillingness—or inability—to play the same set twice. They didn’t write down set lists. They experimented on stage, choosing songs to suit their mood. And they took requests, agreeing to play songs if they remembered how. Like jazz musicians, the members enjoyed improvisation, playing melodies differently, stretching out songs’ bridges, and even taking time to jam freely so that recognizable staples took on new lives each show. They slowed down the classic surf song “Latinia.” They combined songs like their original “Honeybomb” with Link Wray’s “Jack the Ripper.” Like all creative people, they discovered connections between seemingly unrelated things, creating mega-jams from surf songs no one had previously thought to fuse. And rather than vanishing after the performance, fans captured these creations by taping shows that combined into one of the West Coast’s most impressive and overlooked bodies of musical work. The Mermen combined the spirit of jazz, jam bands, surf bands, and ’60s psychedelia into a friendly traveling community. Bay Area shows became happenings as their reputation spread throughout the world. It reached me in Arizona.

I used to think the Haunted House was some Bay Area club. It wasn’t. It was an inside joke. Instead of recording Live at the Haunted House in front of a crowd on a single night, the album is composed of tracks the trio played during three different visits to legendary DJ Phil Dirt’s KFJC radio show, between 1991 and 1994. They’d formed a strong relationship with Dirt, and their radio spots sounded better than their first album.

Of course, after Live at the Haunted House, I had to get everything the Mermen ever recorded. By 1996, there wasn’t much. This was before the era of MP3s, so I had to track down or special order their previous two CDs: 1994’s Food for Other Fish and their tinny sounding debut Krill Slippin’. Then came the incredible studio album A Glorious Lethal Euphoria in 1995, and the short potent Songs of the Cows in 1996. The latter two stayed on permanent rotation during 1996 and ’97 and captured Thomas’ guitar tone more accurately than the first two thin albums. My search for my identity and direction went on and on, and I needed intense music to match the intensity of these years.

People often characterize Mermen music as surf music, and it partly is. By definition, the surf music that arose in the 1960s was instrumental. It had no vocals. Its trebly guitars are loaded with reverb, tremolo, and twang, and often staccato double-picking, and surf bands’ drummers lean heavily on the classic one-two, one-two beat, like in the Ventures’ “Walk Don’t Run.” Despite many similarities, hardcore fans know that Mermen music is more expansive than the genre. For Thomas, it’s more than surf. He didn’t grow up listening to surf music during the genre’s prime. He discovered surf music in San Francisco after they recorded their debut album, Krill Slippin’.

“That happened later, when I moved to California,” Thomas told one interviewer. “In the Sixties I listened to whatever was happening, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones. But I was always attracted to the reverbed guitar tones. Later on, when I had a guitar and a reverb, I liked the way it sounded! It was funny. The Mermen made the first Krill Slippin’ record, and I had never even heard of Dick Dale yet. Then I got turned on to Dick Dale after that, and I was blown away. All of a sudden I started hearing all these bands, I got more into the Ventures. Since that time I’ve played hundreds of Ventures songs, Shadows songs, play Astronaut songs.” Once he found those surf bands, he found more influences, but surprisingly he created his instrumental in kind of bubble, but he also worked to move beyond those influences: “As far as the surf instrumental thing goes, I was always attracted to my own reverb type guitar tone. Later on I discovered the Ventures, which I didn’t know about when I was young. In 1966 I saw the movie The Endless Summer and the soundtrack of that movie got inside me. ...The Endless Summer is the archetypical documentary surf movie, the most famous surf movie ever made. The group that did the soundtrack was called The Sandals and that soundtrack is real beautiful music.”

Music with lyrics often got in the way of my own thoughts, so when I hiked alone, and when I drove the back roads alone, I played this instrumental music so no lyrics spoke over the sound of my own inner voice. Instrumental music was the music of self-discovery. A lack of vocals begs the question of what rock music is for. Is it just for signing along? For catchy chorus and narratives of lost love, broken hearts, summer romance in pickup trucks down by granddaddy’s fishing pond? It’s all that and more. It’s whatever you want it to be. And instrumental rock gives listeners the room to impose all sorts of meanings on the music. For me, Mermen are an almost spiritual soundtrack to a mystical experience. It’s music that lets you build your own world within it.

Despite the maritime, surfy motifs in Mermen song titles—the so called “bondage to the sea”—the maritime elements are more about Thomas’ connection to the ocean than his music’s connection to the surf genre. Critics have described it as “cinematic, expansive, gloriously eccentric rock music” that “does a good job of defying description.” One Archive.org listener called it a “reverb bath.” That’s all true. For me, The Mermen transcend the beach to speak for any wild place with its spirit intact, be it the rugged backcountry or waves breaking along the shore.

Maybe I wouldn’t have clung to this cosmic quality had I not listened to this music while out in the wild of the Arizona-Mexican border, but for me, the band’s psychedelic elements contain something primal, an expansive quality that both evoked my dizzying sense of humanity’s tiny place in the incomprehensibly vast cosmos, and channeled the size of the cosmos itself. When fans describe the music as psychedelic, they mean many things, often about guitar tone and song structure. For me it’s psychedelic because it also felt like atoms spinning, like rays of sunlight, like stars twinkling in thick night skies while camping, of snow falling on ponderosa pine trees, and streams flowing over my toes. I know it’s just music, but music is never just music.

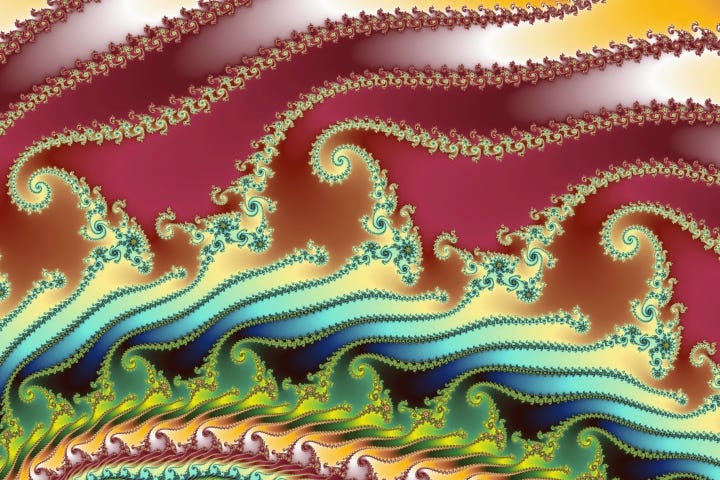

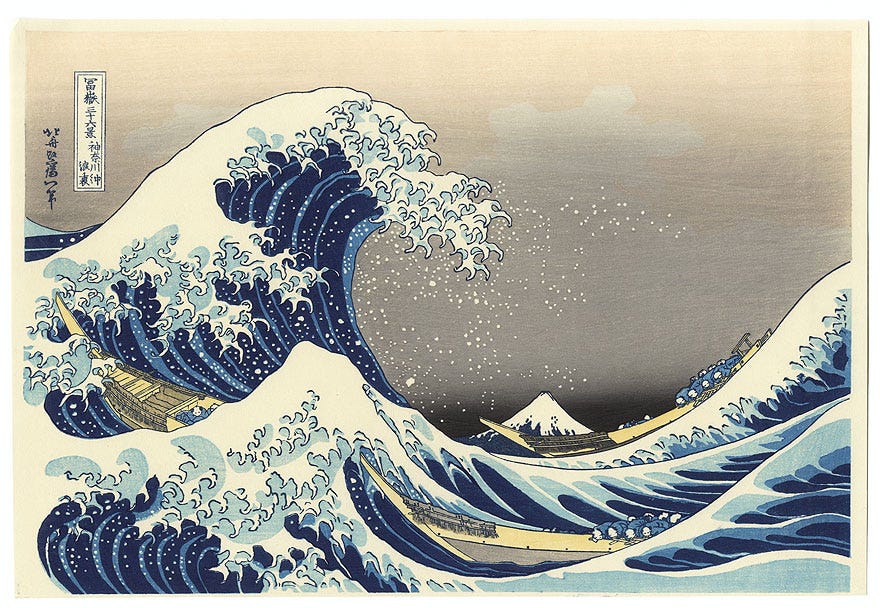

I didn’t yet have that word for it back then, but I had started seeing a certain spiral and branch pattern all over the natural world, formations I later came to know as fractals. I saw them in the ice crystals on frozen streams. I saw them in the shape of curling waves. I saw them in leaves’ veination, the horns of animals like mountain goats, and the gnarled reaching crowns of ancient oaks. I’d started drawing spirals, waves, and repeating concentric rings in my sketchbooks the previous years, generated by what I unconsciously sensed in nature, and what filled my mind while coming down off of acid one night. But it was never the acid that imposed them. They were there in nature. The acid seemed to reveal them.

When I discovered Hakusai’s famous painting “The Great Wave,” I learned what this pattern was, which many thinkers and mathematicians said are the visible representation of the most elemental pattern of nature. It all made sense. When I heard The Mermen, it sounded like an adjective I came to describe as ‘fractalinear.’

Any surfer intuitively knows the fractals in a wave without having to know the term. The Mermen channeled that.

The band’s skill as musicians is obvious. Their song-writing is singular, too, especially compared to the surf revival bands that came up in the ’90s, wearing goofy outfits and playing formulaic versions of Ventures tunes. To me, The Mermen became inseparable from the outdoors where I listened to them, so the music reminded me that we were little upright creatures scrambling around on a spinning rock in a vast empty universe, and connected to me everything. That’s power.

This nature theology influenced so much of my undergraduate life. As a believer in wilderness, I also believed in the power of plants to heal the human body. I shopped at the co-op and consumed spirulina tablets, organic fruit smoothies, alfalfa sprout sandwiches, and lots of green tea. I took herbal tinctures for my liver and immune system, and I read the Vegetarian Times. Back in the 1990s, before chains like Whole Foods made natural foods mainstream, this sort of thinking put you in the margins, where us subcultural veggie types had to work much harder to find good vegetarian restaurants, dairy-free cheese and meatless proteins than we do now. That’s why I went to the co-op. They sold the best plant-based products on the market, and people understood me there. I was trying to connect with Nature through every point of contact I could, from hiking trails to the food I ate. I was also trying to heal my body from whatever damage drugs had caused. The Mermen’s cosmic music was another point of connection.

I knew how crazy all of this nature-stuff sounded to most people. I often sounded crazy to me. I also believed it was true, and I believed that I’d recognized something important enough to examine in an environment outside of class, even as it made me feel like a total freak on campus. Each night, college kids chugged beer on the lawns outside their apartments. They partied at South Padre Island during spring break. They partied at the bars that lined the streets near my apartment. I hacked through brush on the steep sides of mountains and read John Muir’s journals. I took comfort in the fact that past explorers and thinkers had similarly profound experiences in the wilderness. So I read books by as many like-minds as I could: Edward Abbey, Mary Austin, Aldo Leopold, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Janice Emily Bowers, Sartre, Heidegger, Henry David Thoreau. Those people got it. They asked questions as a mode of being. They understood nature’s spiritual and moral dimensions, the magic that infused the unpopulated world. My parents were cool but wouldn’t get it. My friends in Phoenix wouldn’t get it. Hell, my closest friends didn’t even get surf music—they said it all sounded the same—so if they couldn’t hear the splendor in Mermen, how would they ever get my transcendent Thoreauvian head trip? A few 20-something students in my science classes might have understood the allure of unpopulated places. Some professors would have encouraged these sorts of philosophical discussions, but I didn’t take the time to engage them.

Another thing I knew: My philosophy degree wouldn’t do shit for me after college, and that terrified me. But this intellectual endeavor could help me become a fuller, more centered person, at least with the universe and mortality, and could give me a sense of deep direction and purpose. What was more important than knowing right from wrong? Or making peace with death? Connecting to the earth and the cosmos was like learning the alphabet: Punctuation and grammar did nothing if you couldn’t string letters together into words. Spirituality was fundamental. A good job with financial security wouldn’t do me any good if I didn’t have a firm spiritual center. This was how I rationalized constantly ditching of college classes to hike. It’s how I rationalized reading unassigned books by Taoists instead of school assignments. This was bigger than school, I told myself, bigger than a career. Naturally, my grades suffered, but I kept them up enough to avoid failing out completely. Youth is a heady time, so I indulged it. After neglecting my mind and my body for the previous three years while my friends and I partied, it felt like a revelation to engage both mind and body. I was done with the punk rock chemical kind of wildness. I embraced true wildness of spirit. From now on, I would do my own thing.

Only decades later did I learn that something more chemical was going on in my body. I found it in an article, some mention of the way time in nature raises your dopamine levels and can change the structure of your brain. Another study found that people who walked through a park were more friendly and compassionate with other people during the day of their park walk. I had changed my brain by doing too many drugs, and now as I hiked and tried to discern truth, apparently nature was helping change it back.

The Mermen provided the backdrop to all of this. Their music sounds like no era, and yet, its place in my life marks it as deeply ’90s music. As I drove to tackle new back roads, new desert valleys, new old-growth forests, Jim Thomas’ guitar notes echoed through my car speakers. His distortion could sound like a tear in the cosmic fabric. His reverb traveled like light from a distant star taking millions of years to reach my eye. His bright twinkling melodies resembled sunlight shimmering through cottonwood leaves and shadows dancing on sandy creeks.

Each song evoked a very distinct emotional experience: meditative mornings; strenuous hikes with epiphanic rewards; direction and motion; wonder and awe; stunned silence. Maritime motifs were the bands’ experience, not mine. Anyway, many powerful experiences transcended language. I experienced mine alone, without words, without song titles, and this instrumental music mirrored that: a tabula rasa, eliminating the reflexive need for lyrics to narrate experience or tell a story. This was a world of emotion and sound, a place where titles didn’t matter because music shaped that story. And that’s what your twenties are all about: your friends, your future, and writing your life’s story, no matter how winding that path may be.