The Shins’ "Oh, Inverted World" at Age 21

What kind of life do you dream of?

“You gotta hear this one song,” Natalie Portman tells Zach Braff in the 2004 movie Garden State. “It’ll change your life, I swear.”

Remember when music changed your life?

Portman puts headphones over Braff’s ears and plays him The Shins’ “New Slang.” As the guitar strums that recognizable melody and the singer goes “oooooh,” the two characters stare into each other’s eyes, deeply, knowingly—forever fusing this song with the feeling of new beginnings and young love—then Braff tells her, “It’s good. I like it.”

Both the song and the film are about the difficulties of trying to start our adult lives in places we don’t fit. That song reminds me of a time when I was struggling to do the same, after coming out of a deep depression in my native Arizona.

Shins singer James Mercer started writing “New Slang” in 1999, partly as a rejection of the macho music scene in Albuquerque, New Mexico where the band lived, partly in response to his own struggles with life approaching age 30. “The most punk rock fucking thing I could do in my life was something like ‘New Slang,’” Mercer said. “That was just, like, flipping off the whole city. It’s definitely a moment in my life, that sort of angst and confusion about what my future was going to be. The Shins weren’t anything when I wrote that song. There wasn’t any hope for anything like a music career. It’s that end-of-your-20s thing.” Mercer wrote in a relative vacuum at home, recording musical ideas on microcassettes and fleshing them out on his computer, and the troubles he channeled became The Shins’ debut album, Oh, Inverted World.

Like Mercer, Braff processed his struggles through one big project. “When I wrote Garden State, I was completely depressed,” Braff said, “waiting tables and lonesome as I’ve ever been in my life. The script was a way for me to articulate what I was feeling: alone, isolated, ‘a dime a dozen’ and homesick for a place that didn’t even exist.” He created what became the iconic soundtrack by treating it as a personal playlist, gathering songs that wowed him. “Essentially,” Braff said, “I made a mix CD with all of the music that I felt was scoring my life at the time I was writing the screenplay.”

“New Slang” didn’t just change these characters’ lives. It became the sound of the early 2000s and ushered in a new era of popular, gentler indie music that included everyone from Iron & Wine and Bright Eyes to The Postal Service. Sub Pop released “New Slang” as a single in 2001, and its glowing reception moved Sub Pop to release Oh, Inverted World shortly after. It put Seattle’s venerated label back on the map, after the Grunge it marketed had long since died out. Sub Pop released Nirvana’s debut Bleach in 1989. With The Shins, they found a new huge band for a new era. Thanks to Garden State, that shit played everywhere. No matter how sick of “New Slang” you may have gotten after years of hearing it in too many coffee shops and chic boutiques, “New Slang” was the new “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” and the Garden State soundtrack was to the early aughts what the Singles and Pulp Fiction soundtracks had been to the early 1990s. As Spin magazine put it: “It’s amazing that the Garden State soundtrack, originally just a mixtape the dude from fucking Scrubs made for himself, was the catalyst for indie rock to officially enter the mainstream, but thanks to it, the door was kicked open for Arcade Fire and Bon Iver to win Grammys, for Vampire Weekend to score a gold record... Damn straight that song changed your life.”

Oh, Inverted World left an indelible mark on many of us who heard it.

Even now that I’m 47, 21 years after “New Slang” first appeared, new music’s power still moves me deeply, while at the same time, older music brings me back to the time in life when I first connected to it. As potent as “New Slang” is, for me, the album’s other songs “Know Your Onion!” “Girl Inform Me,” and “Caring Is Creepy” hold the most power. They are gorgeous, infectious pop confections, with lovely melodies, deep lyrics, lush harmonies and guitar playing, and constant surprises that overcome the home-recording’s lo-fidelity.

I only started listening to it around 2003, but I saw The Shins open for Modest Mouse in Phoenix in October, 2000. I filmed Modest Mouse. I filmed part of the other opener, the Black Heart Procession. I didn’t film The Shins. No one knew who they were. They were just some local New Mexico band headed back to their home in Albuquerque after touring with this increasingly popular Northwest band. Singer James Mercer had written some of the songs that ended up on Oh, Inverted World by then, but I don’t remember which ones they played that night. I don’t remember much about their set except that the keyboard was loud and noodled across too much of the music for my taste. The keyboardist and drummer were buoyant and excited on stage. The singer seemed serious. Their keyboardist Martin Crandall even dirty-danced on stage, dry humping Modest Mouse’s drum set and fondling singer Isaac Brock. It was a killer show. Like The Shins, I hailed from the Southwest. In 2000, I was young and lost and wanted out, and a few days after this show, I left Phoenix for Portland, Oregon—which seemed like the kind of arty inexpensive place where a young weirdo could make a life. The Shins moved to Portland in 2001 and finished recording Oh, Inverted World up there. In “Know Your Onion!” Mercer sings:

3,000 miles northeast

I left all my friends at the morning bus stop shaking their heads

“What kind of life do you dream of? You’re allergic to love”

Yes I know, but I must say in my own defense

It’s been undeniably dear to me, I don’t know why

When every other part of life seemed locked behind shutters

I knew the worthless dregs we are

The selfless, loving saints we are

The melting, sliding dice we’ve always been

I was a dreg rolling the dice, too, because as he sang:

And I got on with making myself

And the trick is just making yourself

In Portland, those songs became the sound of my adult life starting, the sound of my little dumb engine puttering as I barely took flight from my unsteady adolescence into an uncertain future far from home. Beginnings always mean endings, so that era tinted those songs with a patina of sadness.

When you age, you look back. Some of your music sounds dated. Oh, Inverted World feels timeless.

2022 marks the album’s 21st anniversary, and The Shins are playing a birthday show to celebrate in downtown Portland’s Pioneer Square. I’m taking my five-year-old daughter to see it. How have 21 years passed? How am I forty-fucking-seven-years old? Don’t laugh. One day you will be, too.

Formed as a side-project in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1996 or ’97, James Mercer wrote The Shins’ songs himself, in a style very different than the music his main band, Flake Music, played.

Mercer’s father worked as a Navy munitions officer, later a nuclear weapons specialist, so the family moved around. When Mercer was in sixth grade, his dad was transferred to Kirkland Air Force Base, so they moved to Albuquerque. The desert city shocked him. “I had lived in Germany before that,” Mercer remembered, “and I was thinking, Oh my god. It was like I was in a ’70s teen movie about doing drugs and having sex at too young of an age. It was like one of those after-school specials. It was pretty bad. That was Eisenhower Middle School. It was pretty fucking heavy metal-ed out. I went one year to Eldorado High School and then I moved to England.” He was 15. He struggled to make friends in England, so he spent a lot of time listening to The Cure in his bedroom, imagining what it was like to be in a band, and he learned to play piano. They returned to Albuquerque in 1990 after Mercer finished high school, and he started at University of New Mexico. “I was trying to study chemistry, but I was just not willing to put the effort into it that was required and was having too much fun playing in bands. So I dropped out of school, and I was working odd jobs.”

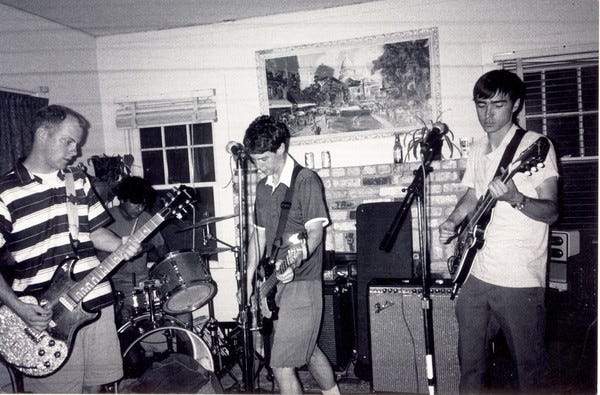

It was a small town, so like minds found each other. In 1992, guitarist Neal Langford, drummer Jesse Sandoval, keyboardist Martin Crandall, and Mercer formed the band Flake Music. Sandoval was still in high school. Crandall worked at a record store. Mercer barely played guitar.

“Neal, the bassist, and I met through mutual friends,” Mercer remembered. “We were involved in a band called Subculture in the late-80s. I remember it because we did R.E.M. covers. …Jesse, the drummer, we met through friends, too. And Marty, we met at a show. He played keyboards for Random.”

Unlike The Shins, Flake Music wrote collaboratively, and Langford was the de facto leader. In fact, he was the one who encouraged Mercer to play guitar and join his band. “I wanted to be in a band, but I was too shy and really didn’t know how to play an instrument,” Mercer said. “Neal and I were into a lot of the same stuff, R.E.M. and The Replacements and stuff like that, so we’d talk about music and hang out. He heard me playing guitar and I think he wanted to inject some new energy into his band Subculture, so they hired me on as a rhythm guitarist. Neal dragged me onstage and got me to start playing.”

Flake Music released a few records and played around. Their sound was very of its era, described as something between Pavement, Built to Spill, and Superchunk.

“We would literally go down to the basement and get stoned or drunk and just riff out,” Mercer told Sub Pop. “Somebody would be playing something that they thought was cool on the guitar and I’d try and sing over it. We were just constantly fucking around, and if we all came up with cool parts and we were all stoked on it, then it could be a Flake song.”

Running counter to the loud guitars and squealing feedback that was popular during the Grunge era, they liked New Wave and “the poppier side of punk,” but they were still a loud guitar band. Mercer eventually wanted to play music that spoke to a different side of him: twinkly, well-constructed, neo-psychedelic pop music. That definitely wasn’t popular in Albuquerque back then. “Anything really macho, really heavy, and aggressive is successful there,” Mercer said.

Mercer loved Pavement and Sonic Youth, but as the ’90s passed, he also fell for stuff like The Aislers Set and Elephant 6 Collective bands like Neutral Milk Hotel, The Apples in Stereo, and The Olivia Tremor Control. He loved 1960s sounds The Kinks, The Beatles, Sam Cooke, The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. Having lived in England during high school, he fell for pensive, intelligent English and Scottish bands like The Cure, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Echo & The Bunnymen, OMD, and Belle and Sebastian, and he wanted to bring some of that English spirit to his new music. “I was longing for something I had experienced in the ’80s with bands like The Smiths,” Mercer said, “things that were really touching and not trying to sort of poke fun at it, but actually being honest about it.”

He also really appreciated solid pop constructions. “If there’s one criticism I have of the music that’s pretty common right now,” Mercer said in 2001, “it’s that no one seems to be trying to actually write songs, at least in the traditional sense. That’s what we try to do: work on new parts and make transitions that make sense.”

By 1997, Mercer was busy writing new songs in his apartment. Initially, he thought of The Shins more as a home-recording project than a band—what he called a vehicle for his song-writing—but he decided it was time to develop and perform those recordings, so he invited Sandoval to play drums as a duo.

“Jesse [Sandoval] and I started out as a two-piece and played our first shows with Cibo Mato and American Analog Set,” Mercer remembered. “After that, Dave Hernandez of Scared of Chaka joined, then Marty [Crandall] and Ron Skrasek, also of Scared of Chaka, got in the band.” Flake Music had written a song called “The Shins” which lent itself well to Mercer’s side-project. “There was something about the sentimentality of the song ‘The Shins’ that I thought was aligned with what I was doing in my recording project at the time,” he said. As Mercer told Spin: “We weren’t very popular in Albuquerque.” In relation to their hometown, Mercer called their gentler pop style “Total rebellion.”

They recorded their first EP in 1998 on a four-track cassette deck, Mercer said, “and it just sounds crazy—the fidelity is so bad.” It’s called Nature Bears a Vacuum. “I wanted to do something that was based on the stuff that I really loved, like old ’60s R&B. I had just really romanticized this whole thing in my head. And so I started recording, messing around with this four-track, and put together this concept of The Shins. Jesse played drums and I’d play all the other instruments. And it’s that Nature Bears a Vacuum thing that I put out myself.”

Although The Shins contained all of the other members of Flake Music, they didn’t view themselves as a revamped version with a different name. Unfortunately, it didn’t yet sound that way to everyone.

“When I started The Shins, I was consciously trying to do something different from Flake. I was focusing on playing percussively on the guitar and I wanted it to sound really different,” Mercer told Alibi News. “But I remember playing the first Shins tapes for a friend and he said, ‘It sounds like Flake with different songs,’ and that’s not what I wanted at all. So we tried to take it in a different direction.”

You can hear that similarity on Nature Bears a Vacuum. The music’s catchy and well-crafted, but it’s as close to Flake Music as it is to future Shins music.

Mercer hunkered down in his studio apartment on Broadway Street and kept writing new songs. He became what others called “a hermit.” He didn’t hang out with friends as much. He didn’t go out partying. He was determined for others to hear the style he could hear in his head for The Shins. Since he was the main songwriter, it all lived in his head. “Maybe around ’98 or ’99,” Mercer said, “I got a computer and my friend got me some black-market recording software, and I started messing around until finally I had a pretty good melody to record with. And that’s when Oh, Inverted World started to take shape. Experimenting with a computer and digital recording made it so much easier.”

Mercer was desperate.

Approaching his 30th birthday, he was reckoning with this future. During the 1990s while he played with other bands, he lived what he called “hand-to-mouth,” in rentals in Albuquerque’s student neighborhood, working the usual low-wage odd jobs that young artists take. For him that meant working as a ride operator at Uncle Cliff’s amusement park, working at a Shoney’s restaurant, working in the framing department at a Michael’s hobby store, and supplementing his income growing weed in his closet. As the end of his 20s neared, he was restless but unsure what to do. Life felt stifling. His relationship was tanking. He loathed his job. He didn’t fit in Albuquerque’s small musical world, with its one main club. Music wasn’t earning him a living. He wrote songs at a rapid clip, but he had little to show for it beyond credit card debt and obscure album releases.

“I had a ridiculous life,” Mercer told Apple Music. “The fun of getting high and doing the stuff you do when you’re young had started to disappear. I would get so stressed out, just thinking, ‘What am I going to do with my life? Why am I in this fucking living room playing video games again?’” Frustrated and uncertain, he turned to his guitar and got serious. “Strangely, I wasn’t really depressed. Because I’ve been depressed in my life. But I wasn’t then. I was just unhappy with so many things that I just wanted a change about my life.” He became determined to either make this music thing work or to accept that he’d tried and failed and had to move on.

He shared his music with his parents—a flailing artist trying to make good to his professional parents—but the loud music Flake played didn’t pique their interest. Mercer remembered with a laugh: “They were like, ‘Are you meetin’ people? Then it’s great. You havin’ fun? You gettin’ laid? Alright kid.’” His dad was also a musician but never played for income. Like many of us in our youth, James seemed to want to give them both a reason to be proud and a reason not to worry. But he worried. “I knew what I was doing wasn’t sustainable,” Mercer said. “I needed to get a proper job. I had higher hopes than working at a factory and selling weed on the side, so I told them I’d try to do some really solid recording work and see if I get anywhere with it, and if I don’t in a year, I’d go back to school. That was my commitment.”

At home writing music, he had more control, and he could buffer his worries and the outside world—closing the very shutters that he eventually sang about in “Know Your Onion.”

“I think early on, writing material for The Shins,” he said, “I realized that there was something especially rewarding about writing a song on my own and—it sounds bad—controlling the whole feel of the song. When that started to happen, it was motivating. I realized that if I found something that I was inspired by, I could work hard. That was a big lesson for me, because I hadn’t been a very disciplined person before that; I didn’t have terrific study habits in high school or college, and I didn’t have any real focus on a target until my mid- to late-twenties. But through this I learned that I had a place in the world, that there was something that I could do that was worthwhile.”

He wrote his way through his worries and malaise, with no sign that it would result in anything tangible beyond the songs themselves. What else could he do? “It was somethin’ I couldn’t stop doing,” he said, “sitting down with the guitar and trying to write songs, because there would be moments that were a thrill. Once in a while there’d be this, Oh, this is a cool fuckin’ thing! and that just keeps you driving.” Making beautiful music was better than feeling as unhappy as he and many of us do in our late-twenties. He sings:

I’m looking in on the good life

I might be doomed never to find

Without a trust, a flaming field

Am I too dumb to refine?

“I waffled about so much when I was in my twenties, whether it was being in the band or just with girlfriends,” Mercer said. “And then you come out of it and you’re like, ‘Not only did I waste my time with that, I wasted this person’s time. They could have, and should have, been off finding something more meaningful.’ But I had a hard time with confrontation and disappointing people. The Shins was the beginning of me taking control of my life and growing up. And it’s not that I didn’t continue to struggle with confrontation and some of the decision-making you have to do as an adult, but that was a big step.”

His natural nervousness also made him work harder. “In order to alleviate that anxiety, I think, if you just work hard, just keep working and make sure you’re doing something,” he said. “And then you don’t have to worry about that. I am. I can be. Not all the time, but it’s definitely a part of my personality.”

In 1999, he had the idea for a guitar and vocal melody that became the main part of “New Slang.” After work making ceramic sconces and pendant lights at a factory, he recorded the idea on an MC-60 Radio Shack microcassette, shaping the melody by mumbling approximations of lyrics he hadn’t yet written.

“I just came up with it and recorded it for a second,” Mercer remembered on the show Demoitis.

Back in those days, he amassed about 30 of these microcassettes. He abandoned the contents of most of them. Very few yielded songs. “That’s a lot of sweatin’ over stuff that didn’t work,” he said. The ones that worked, like “New Slang,” came out pretty well-formed.

“I did two versions of it,” he said, “and then it was done. The funny thing is, when a song works right off the bat, I just generally record it once or twice, and then I never go back to it again on the tapes. I spent a couple hours just going over these old tapes [for this show], and what I noticed was that the ones that end up on the record, I don’t sweat over. It’s weird. The tapes are filled with stuff that’s just mediocre. You can hear me trying to fuckin’ make it cool, like, somehow: And then I added this, now I’ll record it again with that thing—it’s just trying to polish a turd, you know?”

In 1999, he introduced this spare gentle song to Flake Music, but the slow acoustic style clashed with their power pop, and his friends didn’t know what to do with it. Frustrated, he kept working on it himself, and that frustration led him to quit Flake Music to focus on The Shins. “It was very difficult,” he said. “I jumped ship from the overall aesthetic and mode that everybody was in at the time.” He’d liked Black Flag and the Circle Jerks in high school. Now he was consciously rebelling against the indie music world’s faster, harder edge to create something that resembled the oldies he listened to on the radio.

“I was missing those sort of chills that you get when you hear a certain song that’s earnest and really effective,” he said. “I was like, Maybe that could be a thing. Maybe if I work at it, I could get some of that.”

By 2000, he recorded an idea for the B part of that song. When he played the tapes back, he knew it was good. “I liked it a lot,” he told Demoitis. “I was proud of it. I remember showing my girlfriend at time and playing it a lot, and just trying to figure it out: What could it lead into? I knew there was something good there, just in that, and that, you know, don’t screw it up!” Mixed on his HP Pavilion computer in his bedroom, using pirated Cool Edit Pro software, “New Slang” was the sound of his new musical vision coming to fruition, after all his effort and dreaming and frustration. Maybe that’s what the new slang he refers to means: a new mindset, a new style, embarking in a new direction. Maybe it’s code for feelings that exist beyond language.

With more work, he figured out final clear lyrics and he titled the song “When You Notice the Stripes.” He played the tambourine and kick drum himself, augmenting it with a cardboard box. His bassist friend Dave Hernandez came up with an incredible, inventive bassline. And when he strummed the acoustic, he strummed a Gibson J-50 that his dad bought in Honolulu and had given it to James. By 2000, he finished other early Shins songs, including “When I Goose-Step” and “The Gloating Sun,” but “New Slang” really started getting at something new and profound:

Gold teeth and a curse for this town

Were all in my mouth

Only I don’t know how they got out, dear

Mercer later described “New Slang” as a “Saturn return” period of his life, where he felt like “king of the eyesores” and no longer fit in the life he’d made in Albuquerque. “It’s about that time of my life, about getting out of Albuquerque and leaving everything behind,” he said. “‘Gold teeth and a curse for this town.’ I guess that’s like gold teeth being this discovery that I could write songs and that this was my chance, in this talent that I discovered. I was in this place that I felt depressed about. I felt like I couldn’t relate to the people I had been hanging out with. I had become a hermit making a record and recording and lost interest in the bingeing and partying and shit. I would indulge in things but it wouldn’t be much fun. …They call that the Saturn Return, when you’re 28, because Saturn is in the same place. I definitely made a huge change in my life around that time.”

Dawn breaks like a bull through the hall

Never should have called

But my head’s to the wall and I’m lonely

He didn’t care whose feelings he hurt by singing cryptically about his town, or how unpopular his new band was there. He wanted out anyway.

He disliked his situation enough to envy those who’d already found their way: like those bakers at dawn, “may they all cut their thumbs and bleed into their buns ’til they melt away.” Damn them, the happy people. He was happier when he was younger and oblivious, he sang, and now he knew too much:

Turn me back into the pet

I was when we met

I was happier then

With no mindset

It’s infectious catchy for a song about feeling miserably stuck. He gets at that with such sideways poetry and melancholic music that it fits every apathetic young persons’ life without hitting you over the head with it, and he captures a universality with lyrics that never sound familiar. I eventually heard this song so much that I came to loathe it, until enough time passed that I could feel its magic again, because it is loaded with it. What a perfect sad beauty.

Mercer played it for Jesse Sandoval in the kitchen, before the song was finished, but singing those first ‘gold teeth’ lines. “He liked it a lot,” Mercer said. “He was great to have as a muse, because he’d be very open. He wouldn’t be like, ‘It’s friggin’ good, whatever dude.’ He’d be like, ‘Dude, that’s awesome, that’s a cool part, let’s record that.”

When Mercer played his parents “New Slang,” they heard its promise and responded it is spaciousness and accessibility.

Maybe this was his way out.

“I know the bleakness of dead-end job after dead-end job,” Mercer told Spin, “and I finally knew this was my one thing, this is what I do well.”

In 1996, Flake Music had met Modest Mouse when they shared a gig in Chico, California, on what would be Flake’s only tour.

“In about ’98 or ’99,” Mercer said, “Modest Mouse’s Isaac [Brock] called Neal and asked Flake to go play some shows, open up for them in Texas. So we went out and played these shows to, like, 1,500 people a night—it was shocking. We did a combination of Shins songs and Flake songs.” At that time, digital music and its many distribution channels were still in their infancy, but indie music was starting to spread online, where chatrooms and Napster, the first popular, peer-to-peer file-sharing site, could carry musicians’ bedroom recordings to a wider audience. At Shins shows, Mercer handed out CD-Rs that the band burned themselves, and those early recordings ended up on Napster. “We had ‘New Slang’ up there,” Mercer told Apple Music, “and that spread word-of-mouth around town, before there was any attention from outside of Albuquerque. People started coming up to me and just telling me, ‘That song is just amazing.’ They were really stoked, and I was chuffed.”

The bands became lasting friends, so The Shins toured with Modest Mouse in 1999 and again in 2000. “Our friends Zeke from Love As Laughter and Isaac from Modest Mouse kept giving their labels cassette recordings of us,” bassist Neal Langford told Alibi News in 2001, “basically pushing us.”

Sub Pop was looking for bands to sign, so they asked musicians to send them music by new bands. Both Brock and Zeke sent Shins music to Sub Pop. Sub Pop cofounder Jonathan Poneman caught their 1999 show with Modest Mouse in San Francisco and loved it. “There were these great songs,” Poneman said of the show, “this sense of intimacy, this exquisite pop music coming from a place you wouldn’t expect.” When Sub Pop looked at Napster and saw that over 30,000 different servers had Shins music on it, the label took that as evidence that kids were into it.

Sub Pop offered to release one 7-inch single. Naturally, they chose “New Slang,” but Poneman had Mercer re-record it on better equipment to get a clearer sound than he got on his desktop computer.

“I understood what he was sayin’,” Mercer told Demoitis. They used a Roland VS-840 6-track digital recorder to record Sandoval’s drums, which made the drus sound flat and tinny. “I had been using an SM-57 as the vocal mic on everything. I had read that there are microphones that have a large diaphragm that are more for vocals.” But this was Albuquerque. He didn’t know much more about home recording or recording equipment than what he’d read in Tape Op magazine and in a book about home recording written by a guy who engineered Peter Gabriel. To buy a new $300 Rode NT-1 microphone, Mercer only needed to sell about two bags of weed. “I got that,” he said, “and it was like night and day.”

The polished version of “New Slang” went out as a single in February, 2001. Reviews were so hot that Sub Pop turned that one-off single into a three-record deal, and The Shins’ debut, Oh, Inverted World, became one of the most anticipated independent rock releases of 2001 thanks to the power “New Slang.” By 30, the stuck 20-something had turned his fortunes around.

The Shins recorded a third of Oh, Inverted World at Mercer’s apartment before Sub Pop signed them. Now the label gave the band a deadline, so they quickly got back to work on Mercer’s computer. Sub Pop released the results on June 19, 2001. The band moved to Portland from New Mexico shortly thereafter, closer to their label and the buzzy music culture their music friends Modest Mouse were a part of. I’d left Phoenix for Portland the previous year. Lots of us Southwesterners wanted more culture and greenery than we could find at home—and back then, before Portland became a built-up foodie destination and a real estate hot spot, the city was cheap and ignored. Mercer had lived in New Mexico for 11 years. It was time to move on.

“Before you knew it,” Mercer said, “my whole life was upside down: I got signed, I quit my job, I moved out of town, the big relationship I’d had for five years ended.”

As opportunities emerged, his fortunes shifted.

“Probably six months to a year after the record came out,” Mercer told Apple Music, “our A&R guy at Sub Pop, Stuart Meyer, said they had an offer for a licensing deal, but he didn’t want to tell me who it was: ‘It’s fucking McDonald’s.’”

Licensing music to big mainstream corporations was still a touchy issue. In the ’90s it was considered “selling out,” and many fans resented you for it. In the early aughts that was changing.

“At that point, I think Modest Mouse had done a Volkswagen commercial,” Mercer said, “and that was acceptable—kind of classy in comparison. Jonathan Poneman [at Sub Pop] actually offered, like, ‘You can tell people that we made you do it,’ which is generous of him, but I didn’t feel good about that. I needed money: I was in debt from living off of credit cards. I do wish, to some extent, though, that I had known that there were going to be other opportunities. Blonde Redhead had asked us to tour with them, and they were a benchmark of coolness at the time—but all that type of shit pretty much ended.”

Wisely, they still took the money. Why should they have to live hand-to-mouth anymore? They needed to seize their opportunities while the world was still interested in them, because the window is often brief.

The McDonald’s commercial carried the song to a bigger audience than it could have otherwise reached on the radio and MTV, and it eventually reached Zach Braff, who was hand-picking songs for a soundtrack to the movie of his life.

“I didn’t know who Zach Braff was,” said Mercer, “I’d been told that he was in a TV show, and that he wanted to direct an indie film. It was the first time that we had been asked to have our songs in a movie, and I said yes immediately. I don’t ever recall talking about money, so I think we just allowed the usage without asking for any kind of a fee.”

Shins songs spoke to Braff. That’s why “New Slang” spoke to his character, Andrew Largeman, in Garden State, and why “Caring Is Creepy” also ended up on the soundtrack.

You can feel Braff’s angst and personal investment when you watch the film, which matches the way it felt in The Shins’ music, and to me, music will always be the most powerful medium.

The Shins toured and toured and toured, and by 2004, the supposed home-recording side project was a tight performing band as Mercer adjusted to the idea of it.

One night in September 2004, Mercer and his girlfriend slipped into the back of the movie theater inside Portland’s Lloyd Center Mall to watch Garden State for the first time. No one spotted Mercer in there, but when the now-famous scene featuring “New Slang” came on screen, he slumped in his seat, “because it’s so over the top,” he said. “I remember talking to Megan Jasper at Sub Pop, asking her, ‘Are we jumping the shark here? Is there anything we should say no to at this point? Are we really an indie band anymore if we have that big of a presence?’ When the movie came out, we started getting all these offers from colleges and universities across the country, so there was this new market: young adults who were really excited to see us. For the first time we rented a bus with a driver, and we started touring again, basically supporting the movie and the soundtrack. Life is full of surprises. Maybe it’s okay to say yes sometimes.”

I lived a few blocks away from that mall the previous year, so it’s fun to picture this moment happening there, where his little song takes him into the mainstream. That’s what the 1990s were all about: underground bands crossing over. But the ’90s were wrong: There’s nothing wrong with using mainstream channels to bring such beauty to as many people as possible and earn a talented artist a living. The more people hear “Know Your Onion” and “Girl Inform Me” across generations the better. Maybe those listeners will hear something of themselves in it.

Garden State certainly turned The Shins into a working band making a legit living.

“After Oh, Inverted World, I realized I was starting to be able to have an income that was on par with the other 30-year-olds around me,” Mercer told Spin. “I thought, “Whoa. Let’s maintain.” If we work hard and tour, we can actually have a proper life where you could get married and have kids. I remember being 15 or 16 [living in England] and thinking about who I wanted to be when I was 30. I pictured myself as one of those men you see on the Tube; somebody who has a proper job and wears a tie. I remember thinking I’d be some sort of young professional. That was the best I could hope for.”

In 2002, Mercer used the royalties McDonald’s paid for “New Slang” to buy a house in Portland. The Shins recorded their second album, Chutes Too Narrow, in the basement. “I live in a rough neighborhood,” he said in 2003. “The basement isn’t pleasant, but it only costs sixty bucks to buy deadbolts for the doors. It was cheaper than a real studio.”

Chutes Too Narrow contains some real killers. “Saint Simon,” “Gone for Good,” “Those to Come,” “Kissing the Lipless,” “So Says I,” I mean, fuck—those are some of the best pop songs written in the last hundred years, with lyrics sung by one of the most memorable voices of his generation: “You want to fight for this love, but honey, you cannot wrestle a dove.”

Everyone in Portland was talking about this album when it came out in 2003.

I found a fatal flaw in the logic of love and went out of my head

You love a sinking stone that’ll never elope, so get used to the lonesome

Girl, you must atone some

Don't leave me no phone number there

We were like: How did a band this good live here?

Unfortunately, Mercer’s house was next to a crack house. When police raided the house, the occupants blamed Mercer and retaliated by breaking in and stealing musical equipment, including the master tapes for Oh, Inverted World. They didn’t get the original microcassettes, though.

From there Mercer and his wife moved into the house where Elliott Smith’s girlfriend J.J. Gonson used to live. Gonson managed Smith’s earlier band Heatmiser, and when the Portland icon decided to record some solo material for himself, as an experiment in 1993, he recorded it in her basement. Those tapes became his beloved debut solo album Roman Candle. In that same basement, Mercer eventually started developing The Shins’ third album, Wincing the Night Away, in late 2005.

Just as he had with “New Slang,” he’d recorded musical ideas on microcassettes whenever they came to him, be it on the road or between tours. By the time he started fleshing out songs, his insomnia was scrambling his mind, so it was a slog. Along with fighting it, he tried to harness it, working in his home studio at whatever time he woke in the middle of the night, until dawn. “I took this chaos in my life, chopped it up into bits, and made songs of it,” he told Spin. “It was difficult—I got sick of thinking about this shit. But now there are these little pop gems. It’s a great feeling.” He also got help from producer Joe Chiccarelli to shape the material and correct certain mistakes he’d made doing home-recording.

“When I hear Oh, Inverted World,” Mercer told Apple Music, “I hear myself being overly ambitious, just putting so much stuff in the mix. I would have a ton of melodic ideas and I would just cram them all in, and I think I should have edited more. One thing I've learned is that you need to let the best moment in a song shine. On ‘The Celibate Life,’ for example, there’s just too much going on, and I should have let the harmonica do what it’s doing for a second, just to give it a spotlight. I should have let the guitar shine, too—you can barely hear there’s a really cool guitar solo, but it’s all in the mush of the rest of the stuff going on. You have to pick and choose, and you have to delete some stuff. I still have trouble with that.”

Wincing is the direction Mercer wanted his music to go: leaner, more focused, more polished but just as poppy and direct as ever.

It’s a great album. Wincing the Night Away has some potent songs, like “Sea Legs,” “Sleeping Lessons,” and “Phantom Limb.”

In songs like “Australia,” he achieved the sound of The Smiths that he’d aimed for back in his New Mexico bedroom—those delicate high choruses, the nimbleness and buoyancy, channeling both Morrissey and Johnny Marr. “I think I wanted to challenge myself production-wise and come up with something new,” he told Alibi News in 2007. “I think that’s what makes a record that kind of grows on you as opposed to being right up front. I was challenging myself, like, ‘How can I take this pop song and make it really artfully done?’” The band achieved that. The album debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard charts and sold 118,000 copies during its first week, making it Sub Pop’s most successful debut ever. Then it was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album.

Chutes Too Narrow is even better. Loaded with more perfect pop songs and total heartbreakers, it is, song for song, a more consistent, higher-fidelity album than the rough bedroom pop of Oh, Inverted World and polish of Wincing the Night Away, proving once again how much better independent music often is than mainstream music. But still, it was Oh, Inverted World that attached itself to a pivotal period of my life that I could never uncouple it from, a time in life when you feel things more intensely than you ever will again—about heartbreak, about listlessness—and those emotional attachments go beyond the music.

Mercer also recognizes that their debut contains elements that no subsequent Shins album could ever contain, because it’s the result of a fleeting time and place, and it contributed to the character of the world it came into. “It’s also something that stands as a bit of a pinnacle for our band,” he wrote in a 2021 press release. “You release that first record and it’s so well embraced, but you’re always trying to get that magic back, I think,” he said. “We’ve done well, certainly, but the fervor that happened around Oh, Inverted World we never quite reached again.”

That magic is why I had to stop listening to it for a number of years: It brought back so many feelings that I needed a break from. That magic is why I’m still listening to it decades later.

For those of us lucky enough to have parents who love music, as kids, we grow up listening to the music our parents play around the house before we discover our own. My parents played Linda Ronstadt, The Carpenters, and Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. My wife’s parents played heartland bands like Bread and America. My wife and I play our daughter Cat Power, Sleater-Kinney, and Miles Davis.

When Natalie Portman tells Zach Braff, “You gotta hear this one song. It’ll change your life, I swear,” it’s no sentimental line. When I play our four-year-old daughter music, I want some of it to change her life, and I want it to build a love of music outside of the moments it attaches to—to give her the gift of life as a listener.

This July morning before dropping her off at preschool, I played her The Shins’ “Gone for Good” on my acoustic guitar. I sat on a living room chair, and my wife sang “Untie me, I’ve said no vows / The train is getting way too loud” while I strummed and mangled parts with my bad bar chords, but we got the gist together. The feeling was there. Our daughter felt it and smiled, even humming her own melody along with us.

Standing beside me, she asked, “Who sings that?” I told her The Shins.

“They live here in Portland and I’m going to take you to see them play in a few months,” I said.

“Here?” she said. “In Portland?” She stared into space while taking that in, then she requested we listen to a song by a singing dragon from her favorite show Rescue Riders on the drive to school.

These are her final three weeks of preschool. She turns five soon and starts kindergarten soon after. It’s cliche because it’s true: Time flies by as a parent. That’s because life does.

We spend so much time trying to make our way in the world that if we get there, it’s easy not to know what to do. Then as we age, we spend a lot of time trying to get back home, if only in our minds. In that living room, I had arrived. Whatever had confused and depressed and obstructed me in youth no longer registered as a 47-year-old dad. Moving youth’s boulders delivered me here with my two favorite people, singing in our living room. I live for these quiet moments now. They are my happiest times. It’s then that I know that there is nowhere else to go, only here, with them. Playing certain music with my family scrubs it of my old sadness and repaints it new colors, family colors, so it can let me feel new things again.

At 21, Oh, Inverted World still conjures my distant past, but it also signals the future. Our kids grow so quickly, and one day my girl will leave the nest and have her own struggles, and she’ll develop deep attachments to songs that will empower her journey and that will capture its difficulties—even songs that she’ll play for us when we’re old and out of touch. Right now she mimics me and wants to be with me all the time, but one day she’ll want space, so much that she’ll move out and labor to make her way in the world the way Mercer and many of us did. Then, like me, she’ll have songs that remind her of that time, and songs that remind her of us—her parents—on mornings like this, when we watered the yard together and made pancakes together then played in the living room for no reason other than to play, because we were still young and able. One day, she’ll have her own Shins.

As Mercer sings, she’ll get on with making herself. Hopefully she won’t also have to leave all her friends at the morning bus stop, shaking their heads, but she will have to ask what kind of life she dreams of, and hopefully, she’ll be guided by something she holds undeniably dear, even if she doesn’t know why.

As she enjoys the last carefree days of preschool, I can feel time speeding up. Parents’ hearts break piece by piece just as they swell with joy, and watching her run toward her friends in her preschool’s yard, I finally appreciate the pride and pain my own parents felt as they watched me struggle to build a life for myself—and the relief that someone like James Mercer’s parents must’ve felt watching him transform from a flailing songwriter to an internationally known, working songwriter. We all hope our kids find themselves and sure footing. Some of us also hope our kids find the music that will take them there.