Trading Letters and Music With Other Depeche Mode Fans

In the 1980s and '90s, hardcore DM fans mailed each other tapes and rare music and become pen pals in the process.

In the 1980s and ’90s, before digital media changed the way we bought and listened to music, people bought physical copies of albums at traditional brick and mortar music stories like Tower Records and Sam Goody. But sometimes bands’ official albums weren’t enough to satisfy. We needed concert recordings, unreleased demos, and obscurities. For that, we went outside official commercial channels and bought bootleg recordings and traded stuff with other fans.

Diehards still go to extremes to get the music they love. Back in the analog era, fans would copy music onto blank cassette tapes and CDs and mail them to people through the post. This was called “tape trading.”

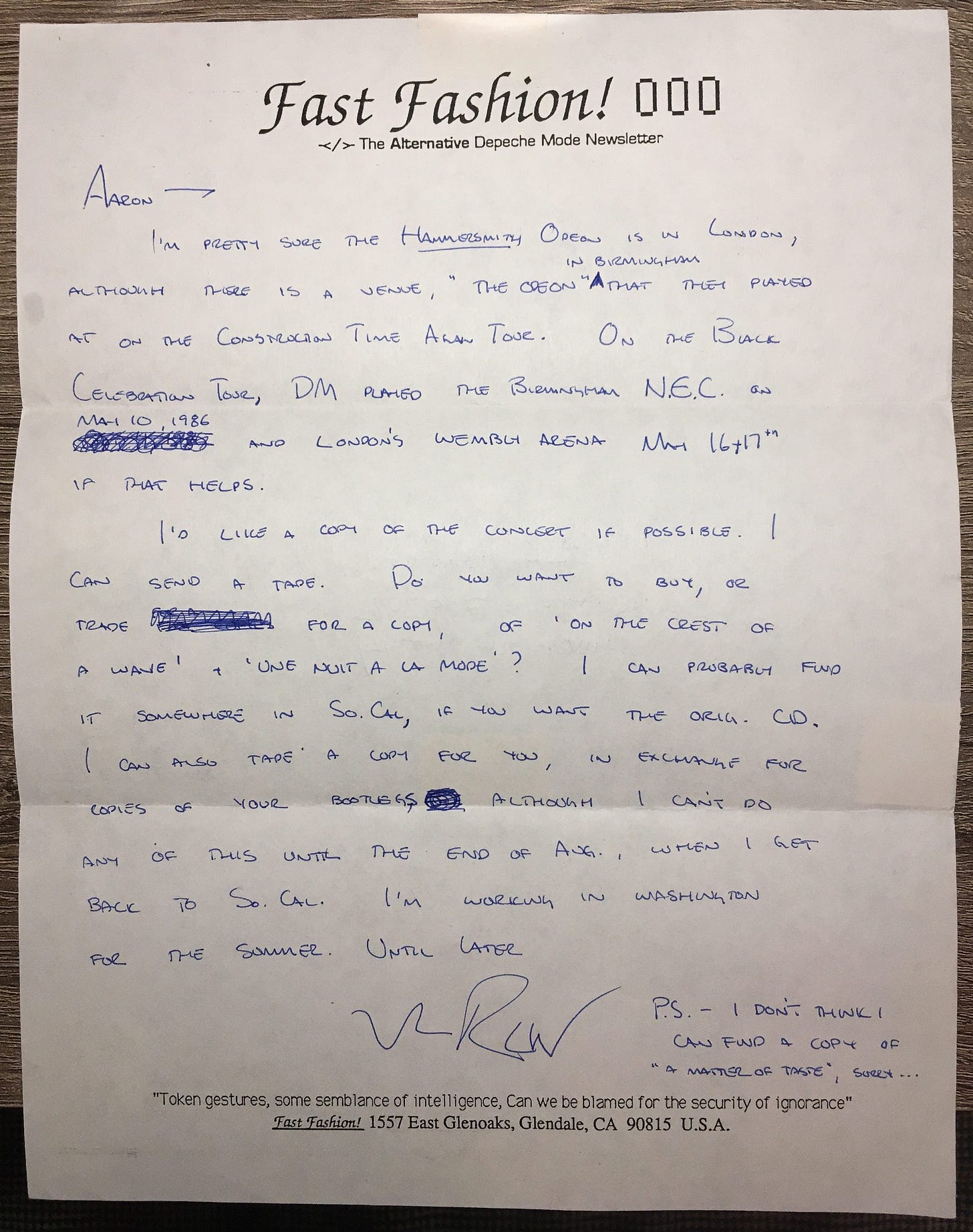

Many bands released live albums. But maybe the live album was only from one year of your favorite band’s long life. Maybe you wanted to hear concerts from all the other years the band toured or hear music from their earliest years as a band, or from a particular tour where they played different songs. Thankfully, so-called bootleggers had been smuggling recording equipment into concerts for ages. Unofficial live recordings capture a certain heat that studio recordings often lacked. Live recordings often include cover songs the band never released on their albums, or different renditions of their own songs, and some of us liked that. So fans would buy those bootleg concert recordings. They’d get hold of John Peel sessions from the BBC. They’d record radio broadcast off of their home stereos and got vinyl copies of concert recordings meant for radio DJs, not for regular listeners. And then they circulated copies of those recordings among other fans.

Tape trading was awesome.

It violated certain copyrights and contracts, so it pissed off many record companies and musicians. But many bands tolerated it, because the fans wouldn’t appreciate their musical idols trying to cut off access to music—remember Metallica’s response to Napster?—and some bands made enough money in the record industry’s golden years to endure the loss of revenue from these unofficial recordings. Some bands, like the Grateful Dead, actually allowed fans to record and trade copies of their shows.

Audio streaming technology, contentious file-sharing platforms like Napster, BitTorrent sites like Pirate Bay, ended tape trading in the early 2000s by replacing it with more sophisticated and immediate methods. Although some devotees continued the practice—and even revived it—as a nostalgic hobby, it’s an artifact from the analog era.

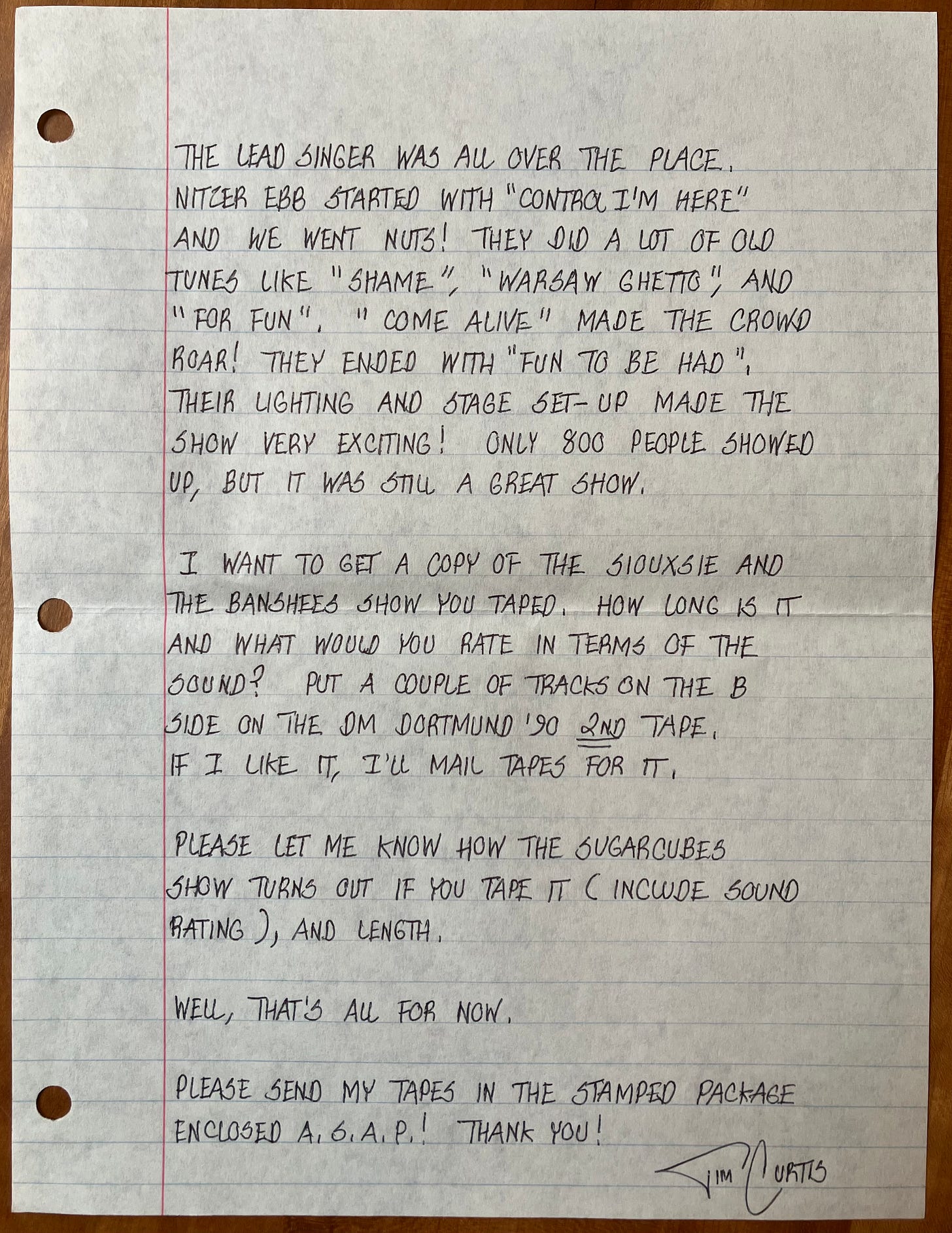

Another cool artifact? The letters that fans mailed to each other along with those tapes.

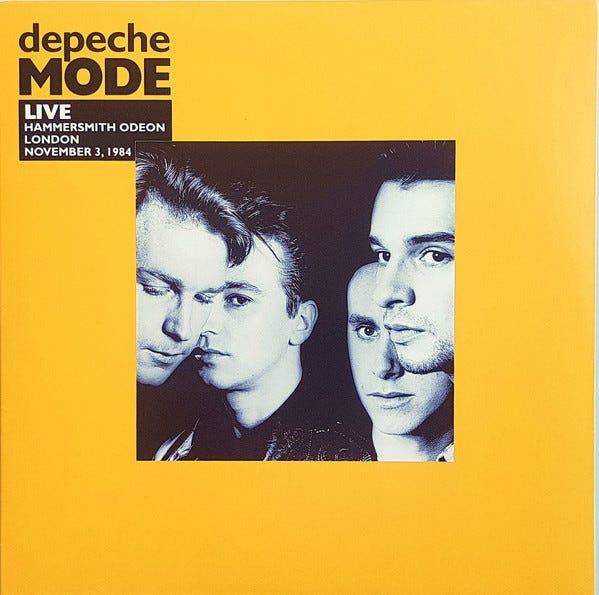

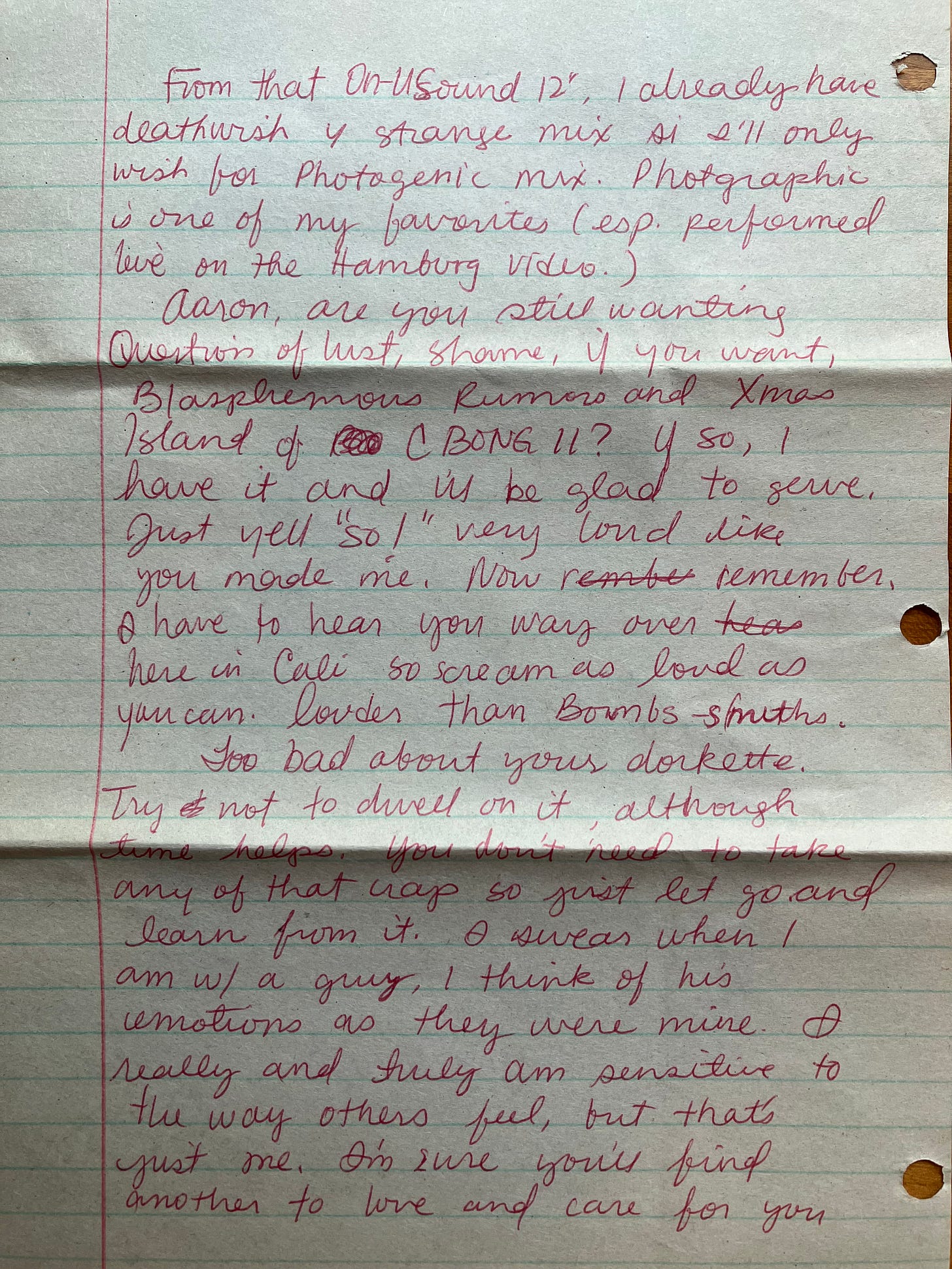

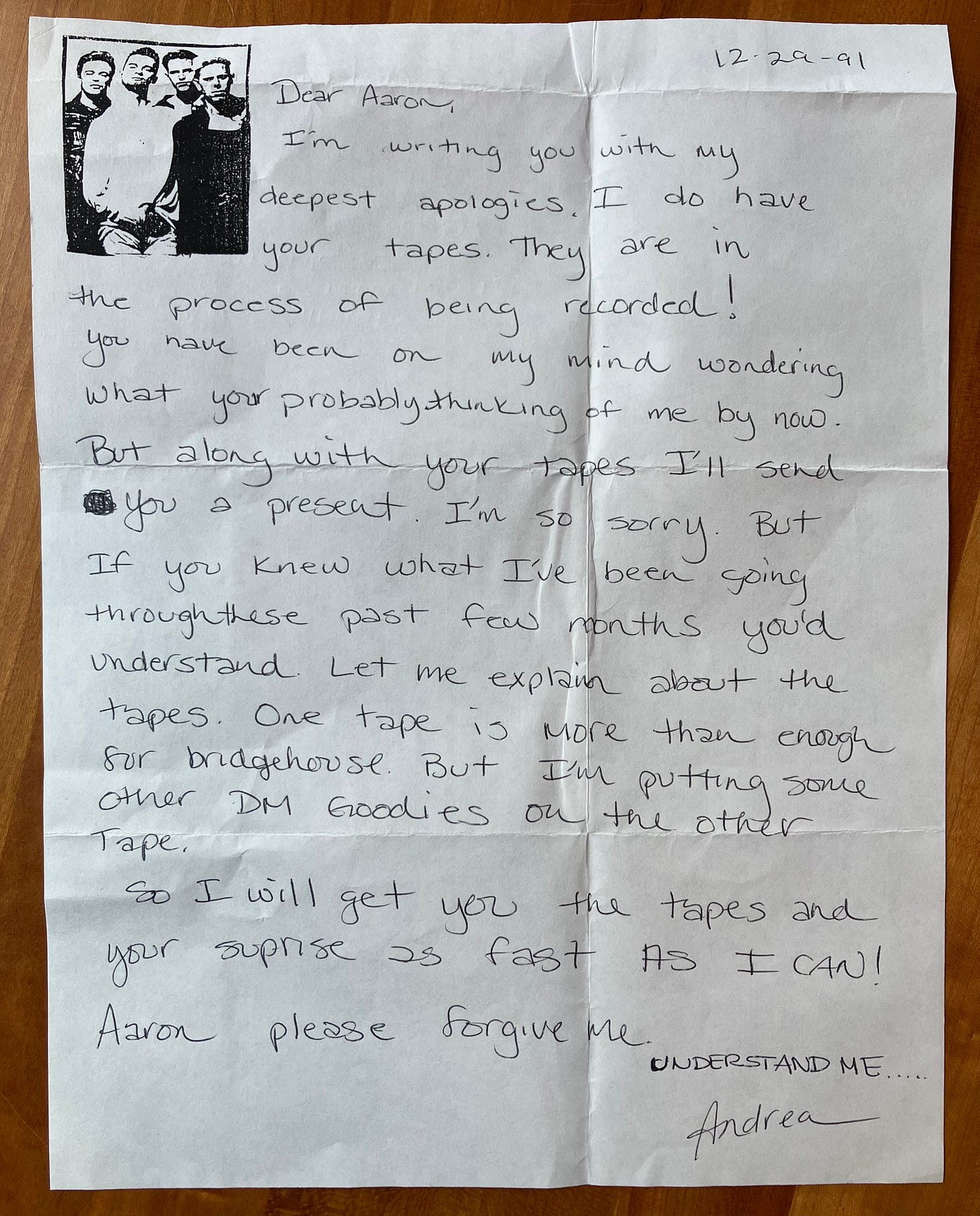

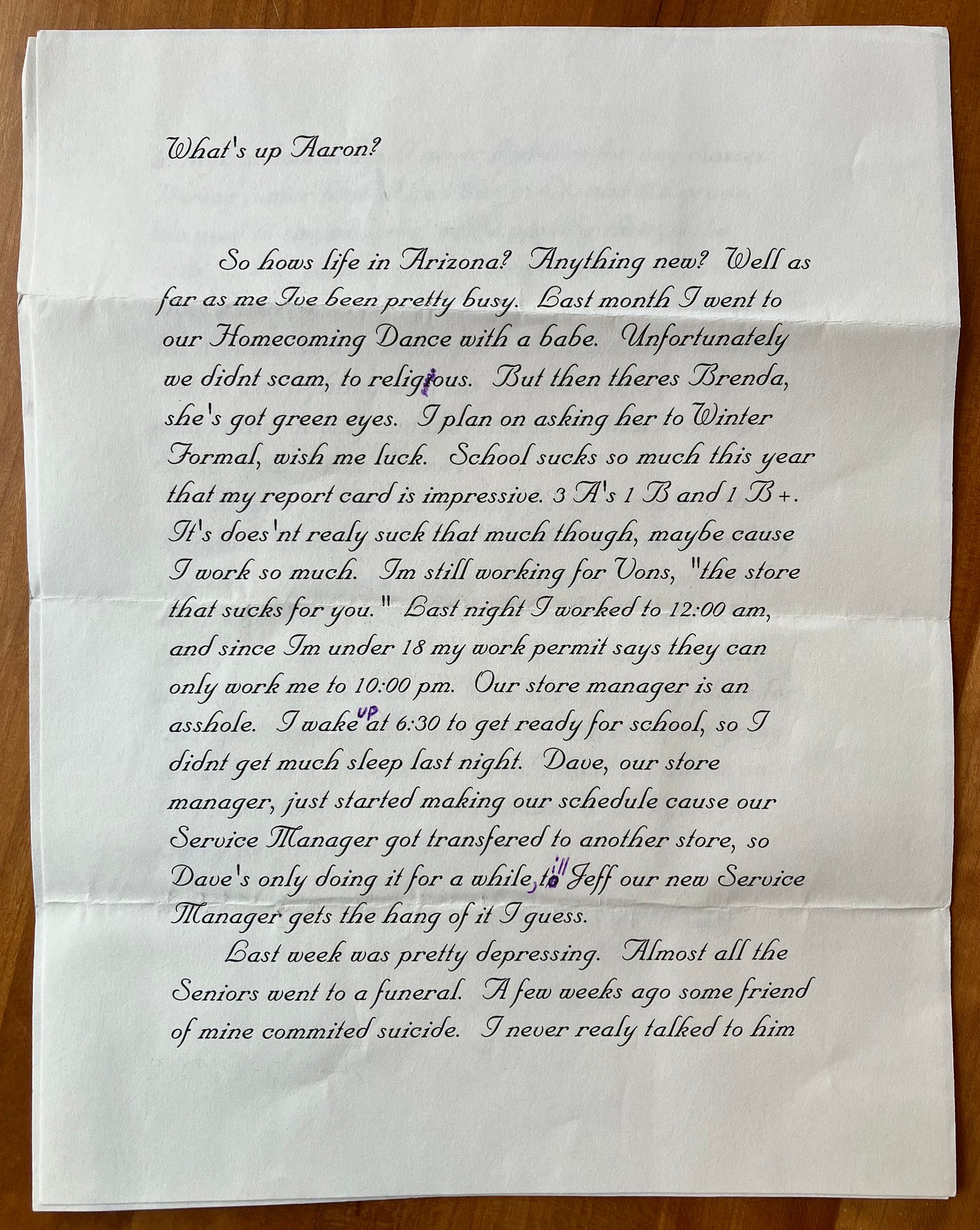

I saved all of my Depeche Mode fan letters from 1991-1992!

I’ve told this story before, but in 1989, I started high school as a huge Depeche Mode fan.

In seventh grade, a tight-knit group of female classmates had become obsessed with Depeche Mode. These girls sported their black DM concert tees in class. They chatted about the wonders of the Black Celebration album and longed for the band’s next Arizona performance. And they joked that they were married to their self-appointed DM “husbands.” Kristin wed herself to singer Dave Gahan, Nikki to songwriter Martin Gore, Kari to keyboardist Andy Fletcher, and Laura wed herself to the quietly powerful Alan Wilder. These girls were so cool to me. Their excitement was exciting, even though my skater friends and I teased them about it. Curious what about these Brits that had them so enamored, I bought DM’s album Music for the Masses because it appeared on some of the girls’ shirts.

While spinning the LP alone in my room, I discovered a partial explanation: DM’s music was profoundly different. It had haunted melodies, inventive percussions, and it created a moody ambiance by layering orchestral synthesizers with field recordings that the band made by banging on metal and revving their car engine. DM struck me drunk, which was a sensation as mysterious and domineering at age 13 as a romantic crush.

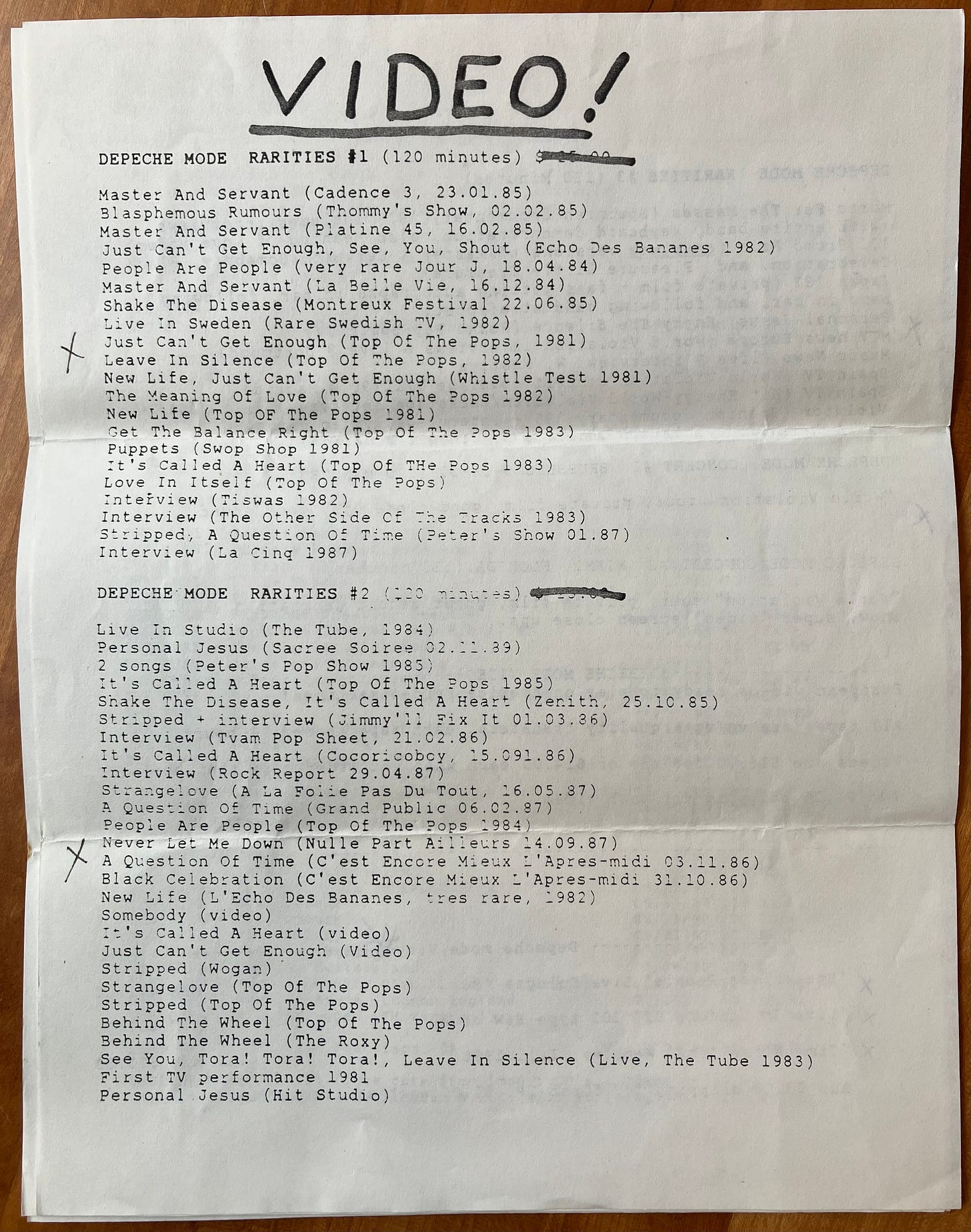

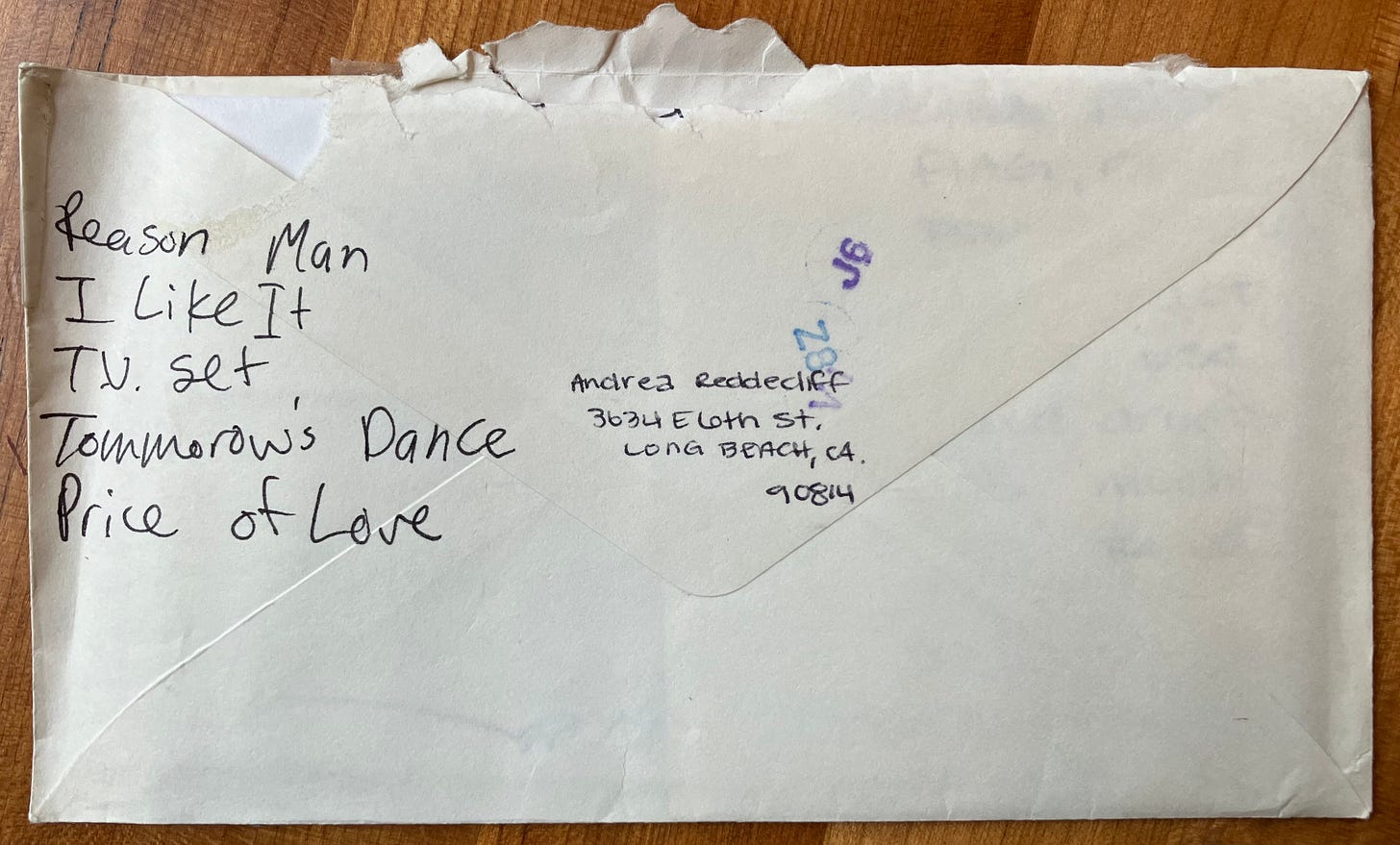

I spent weekends riding bikes with friends to record stores, searching for over-priced imports featuring multiple dance-remixes of single songs with names like the “Renegade Soundwave Afghan Surgery Mix.” I coated my bedroom with posters, painted the letters “DM” on the wall beside my bed, and mail-ordered concert tees from tours I was too young to attend. I ordered fan-made magazines and newsletters and read about ultra-rare, early-80s live recordings from places like London’s Bridgehouse Club that contained unreleased songs like “Price of Love,” “Television Set,” and “Reason Man.” These were considered holy grails in the fan community.

I wanted them. Before the internet, you relied on printed material and other fans for information, and information was scarce.

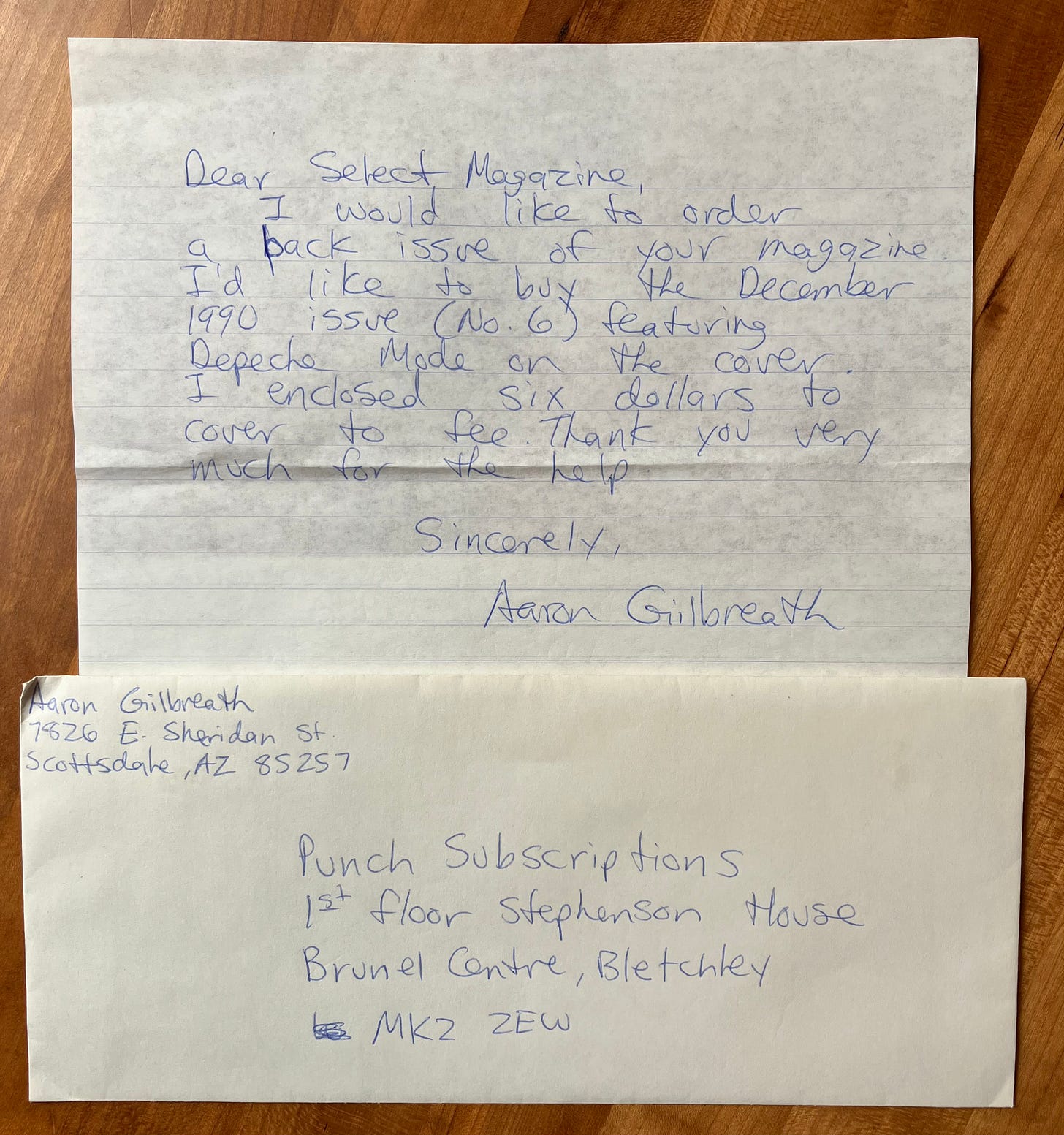

So I wrote to some English magazine called Select that once had DM on the cover.

And I wrote to a New York company that had pressed a rare recording to vinyl, and the letter got returned. I didn’t realize it was bootleg record and the company wasn’t legit.

I quickly learned that the best way to get rare live recordings and information wasn’t in record stores. It was from fans.

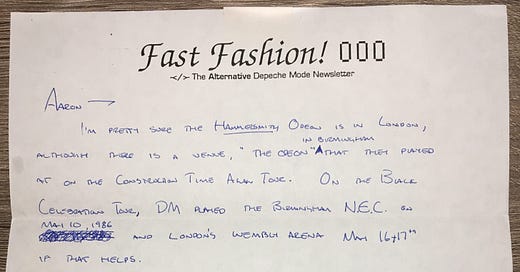

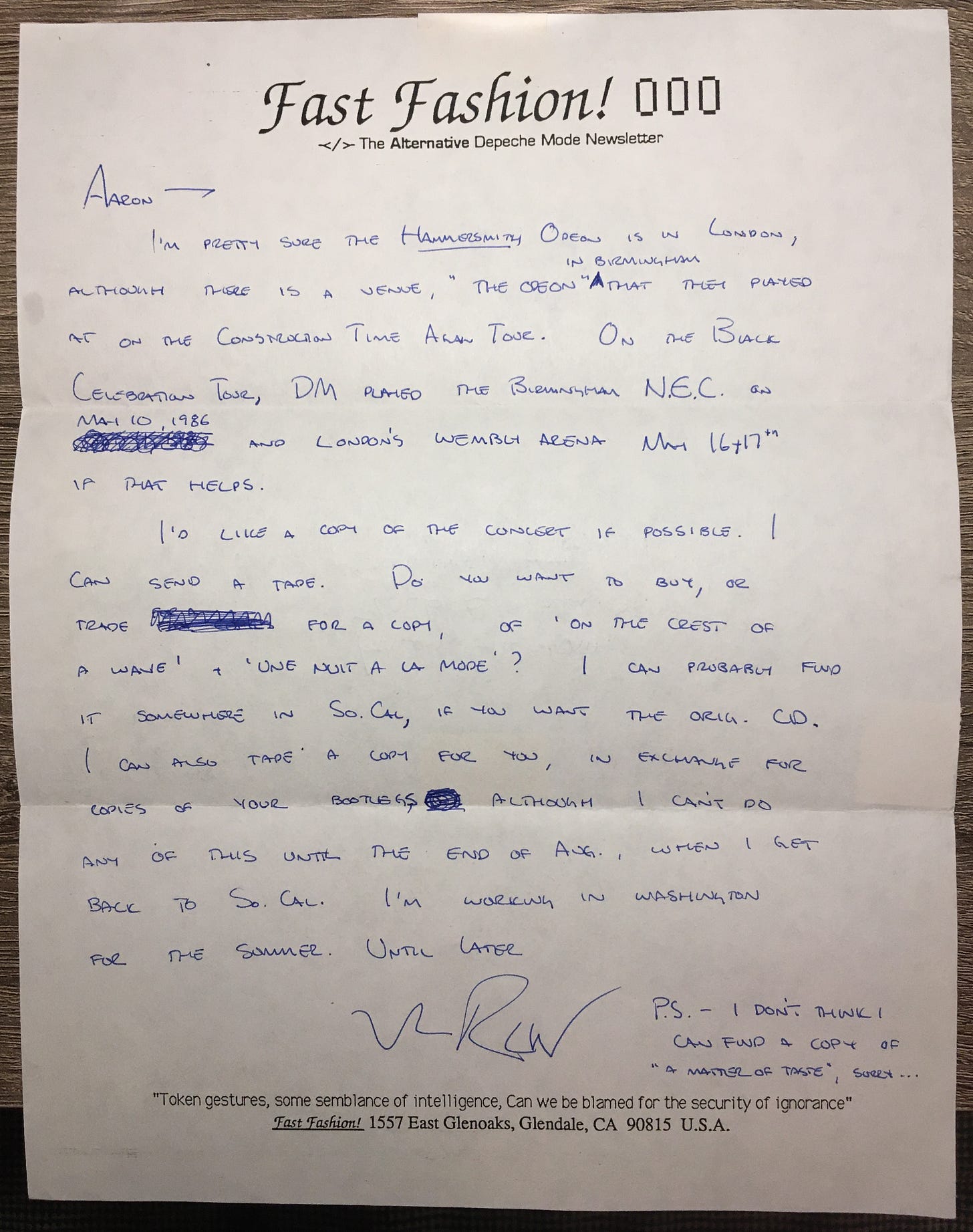

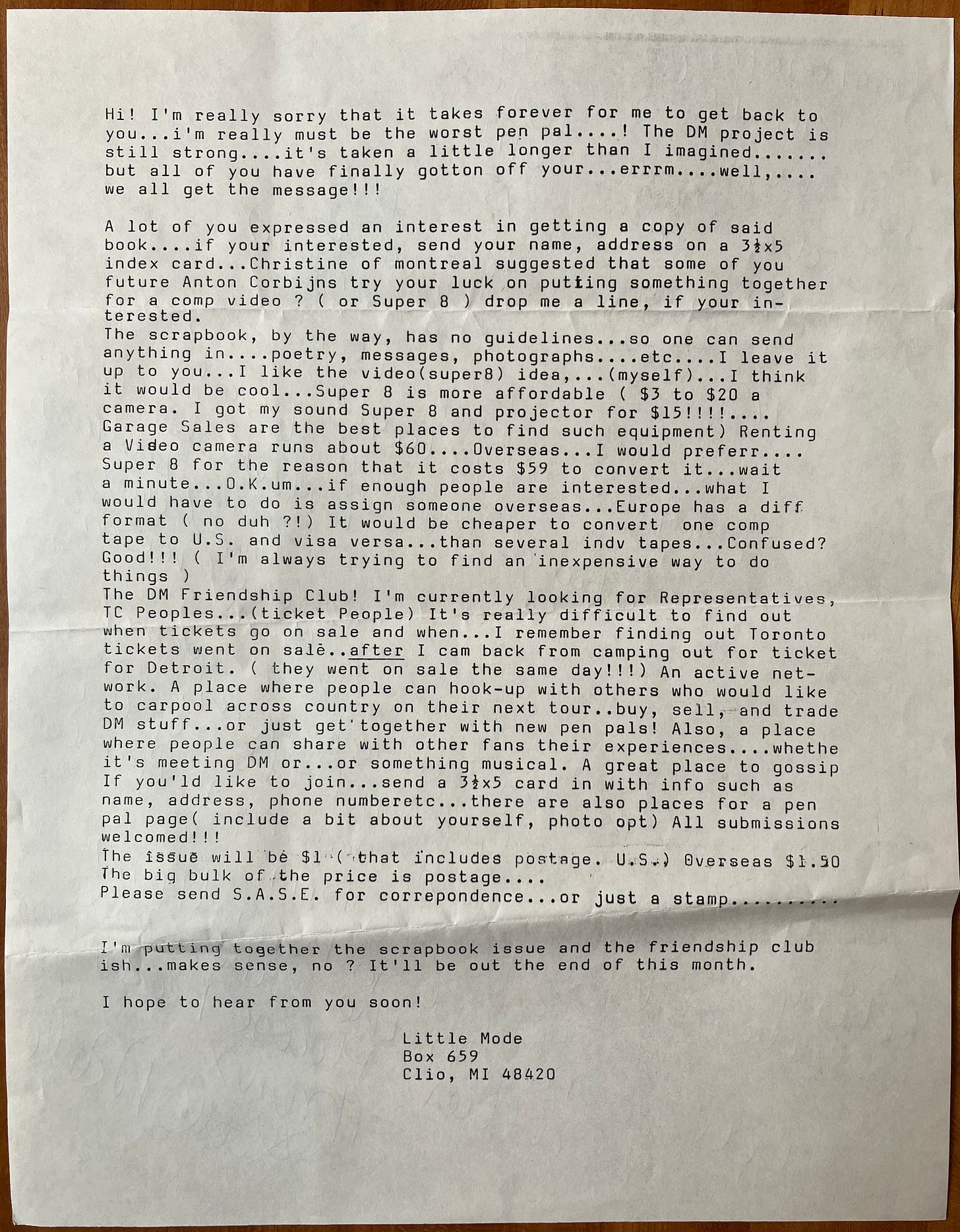

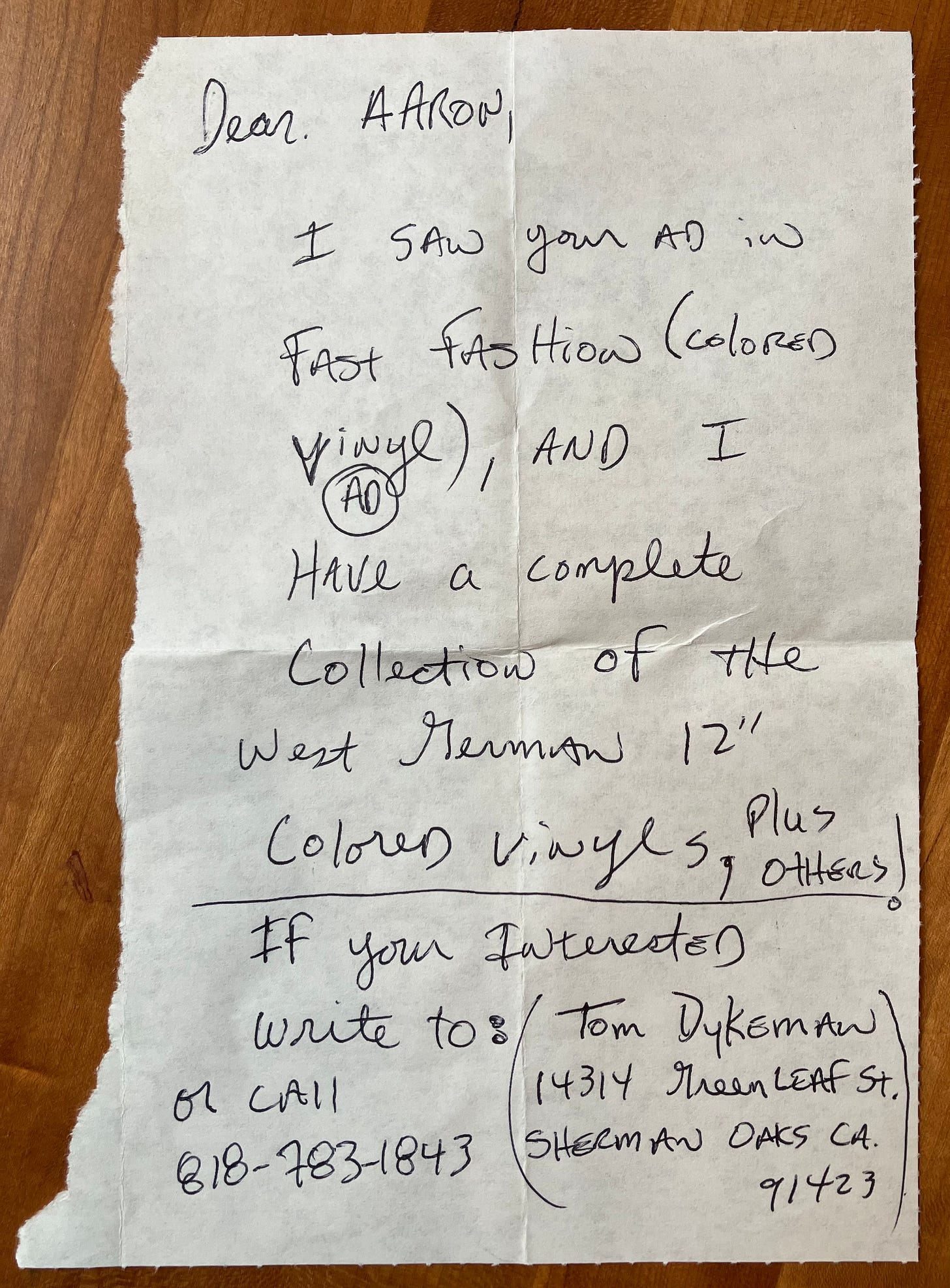

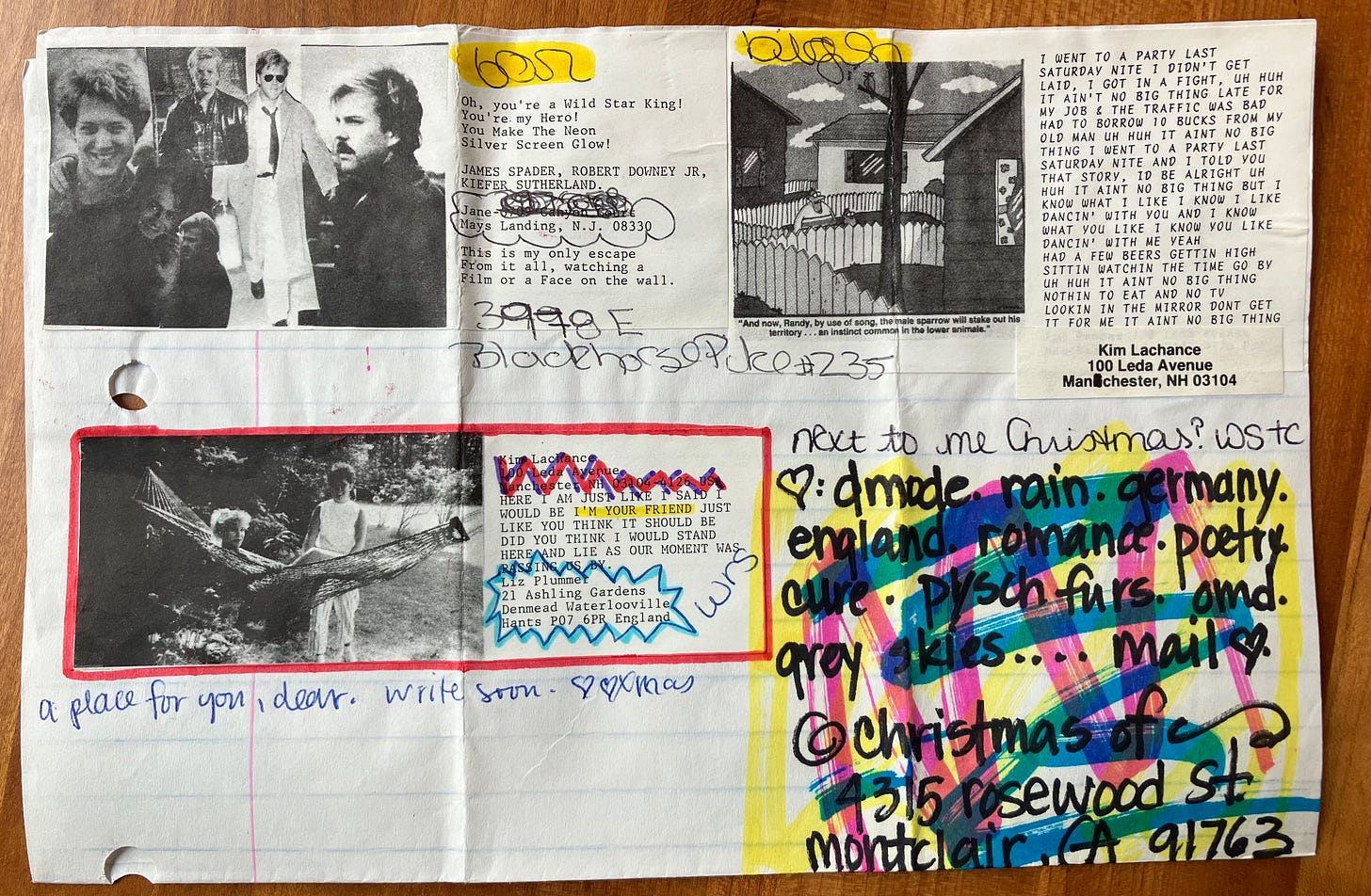

It was hard to tell where to start, so I wrote to the person who ran Fast Fashion! The Alternative Depeche Mode Newsletter. She wrote in stylish all-caps. She had an out-of-state job. How old was she? She was so kind:

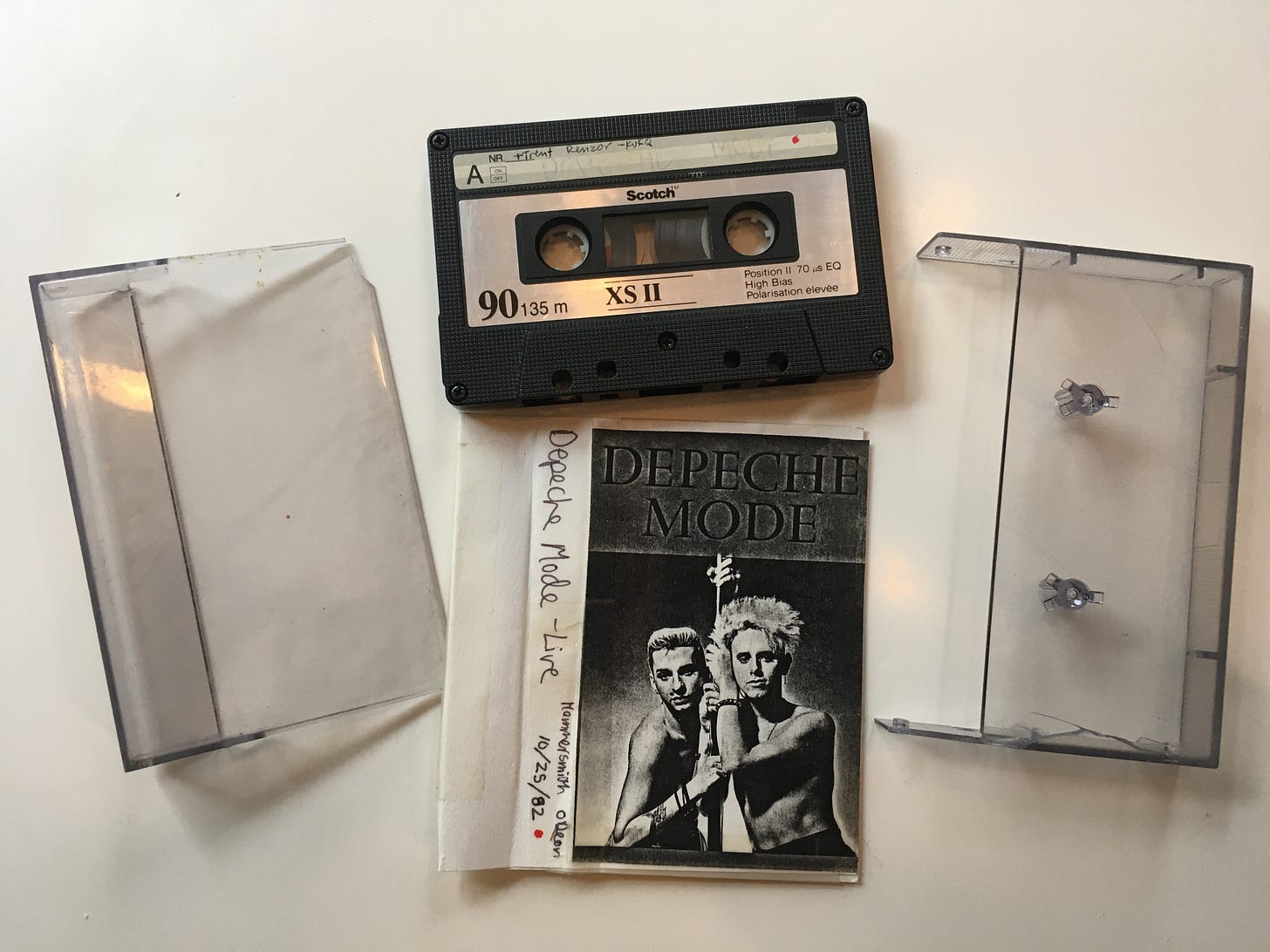

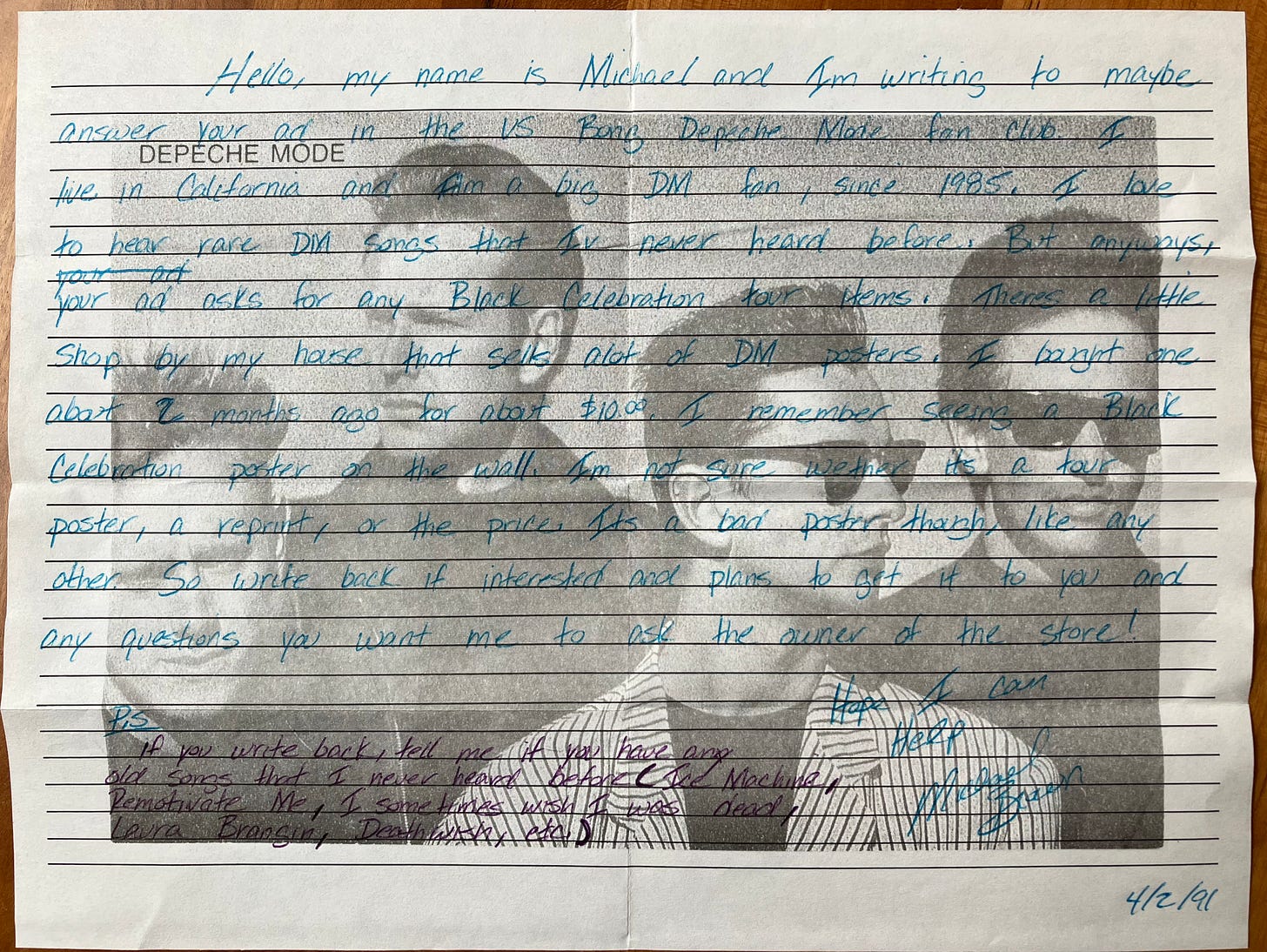

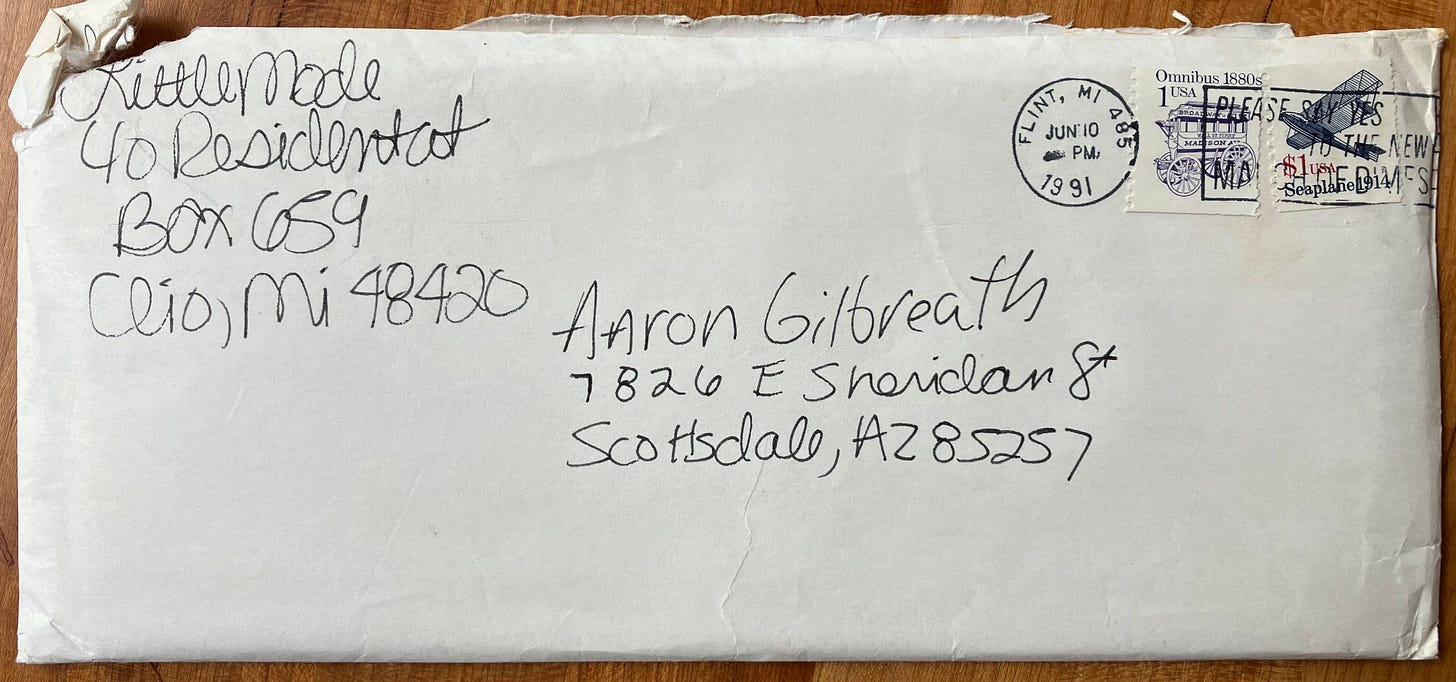

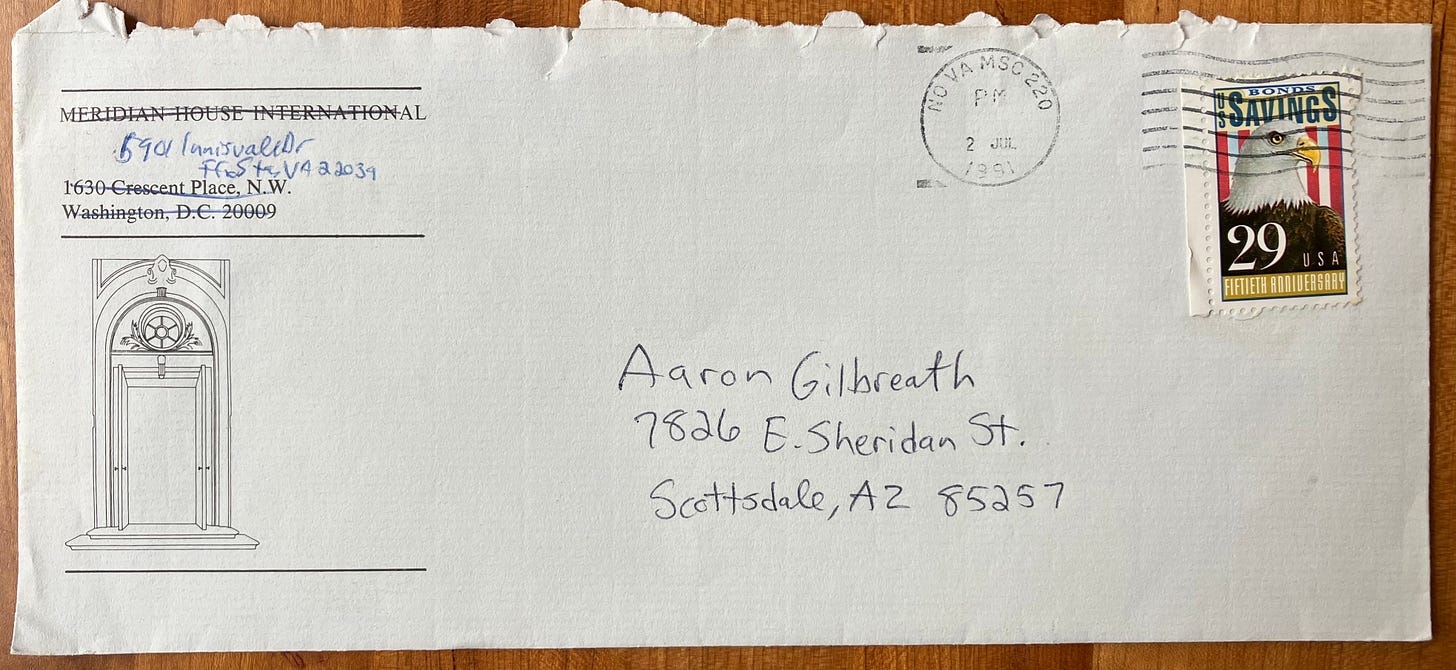

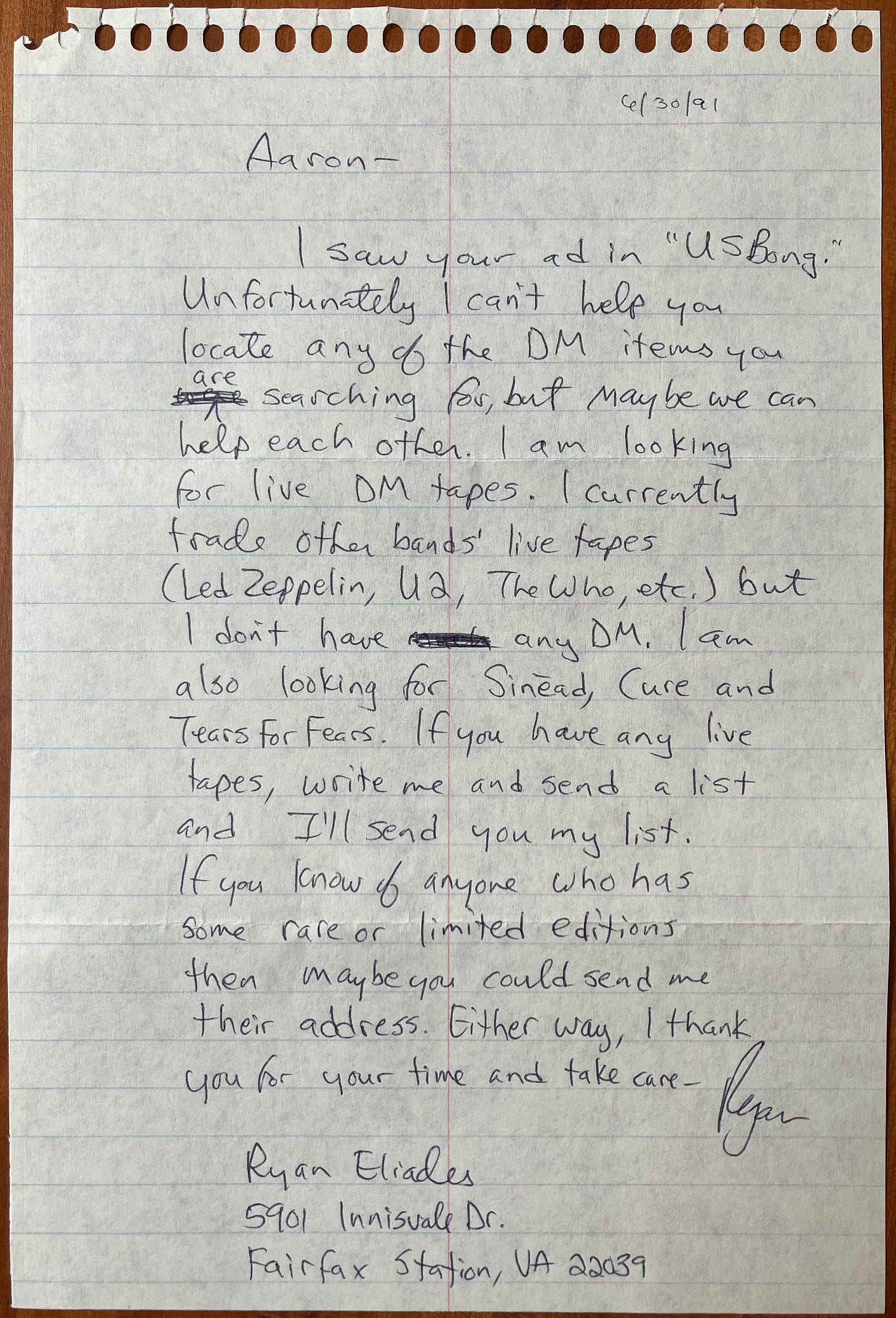

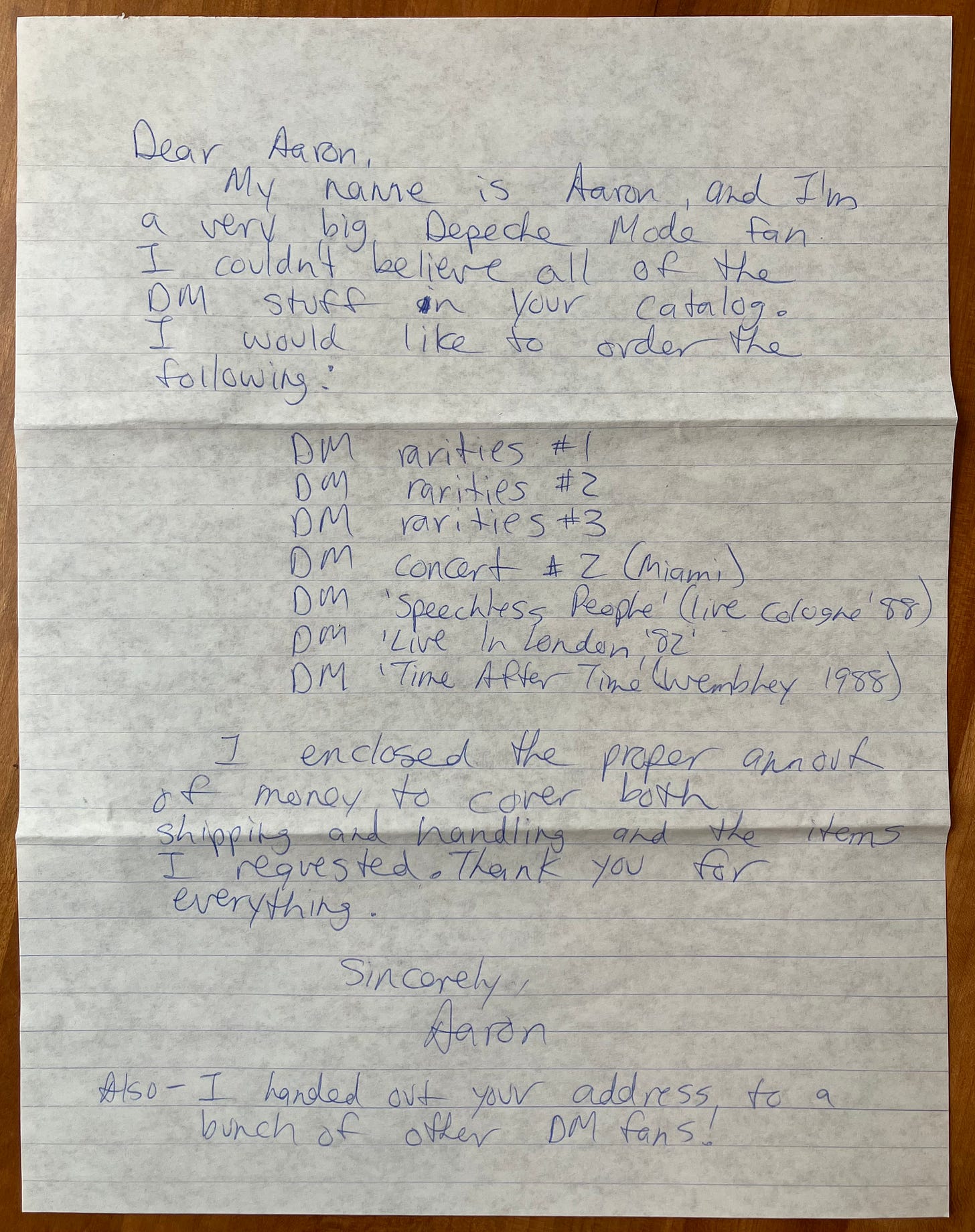

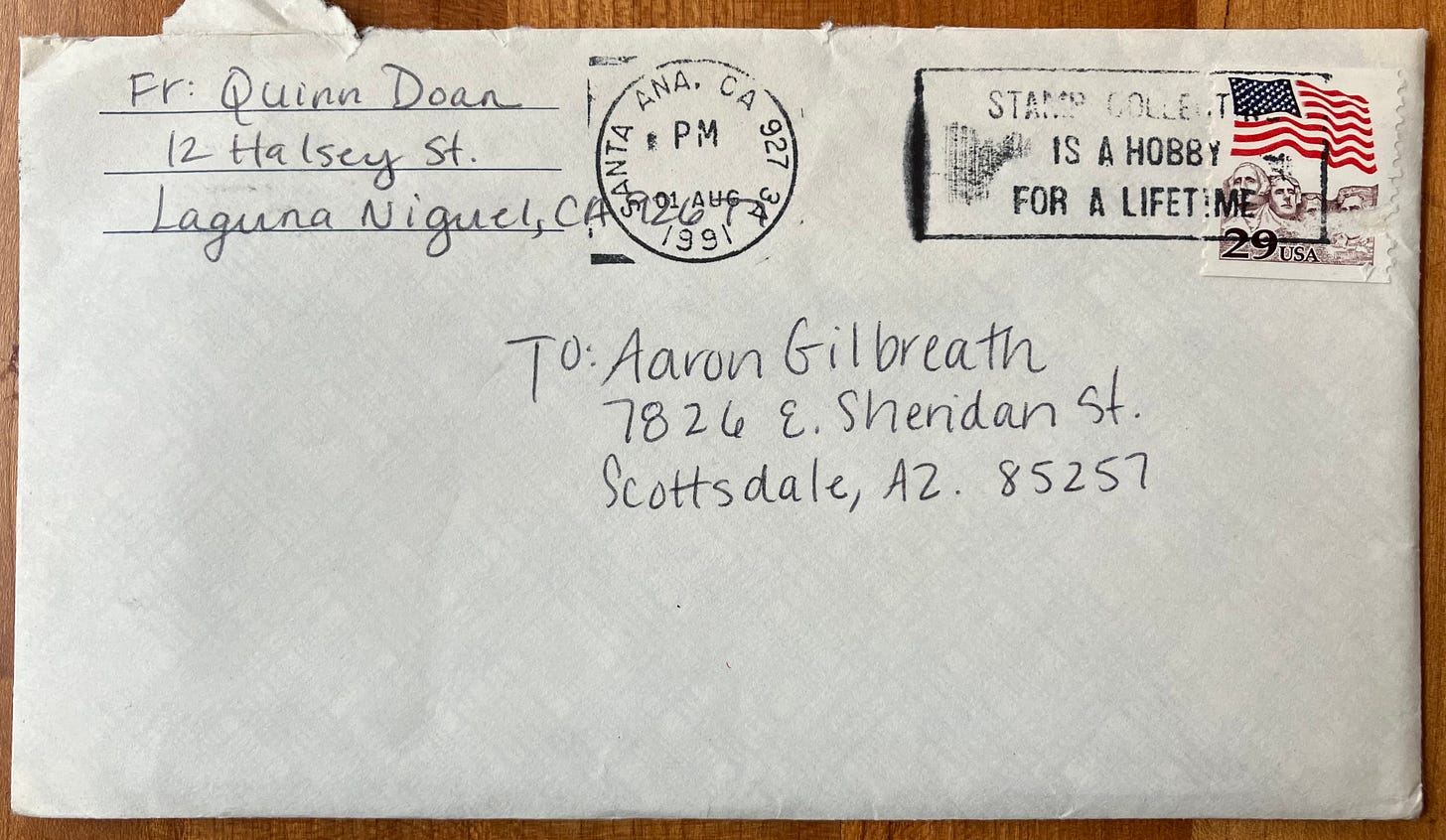

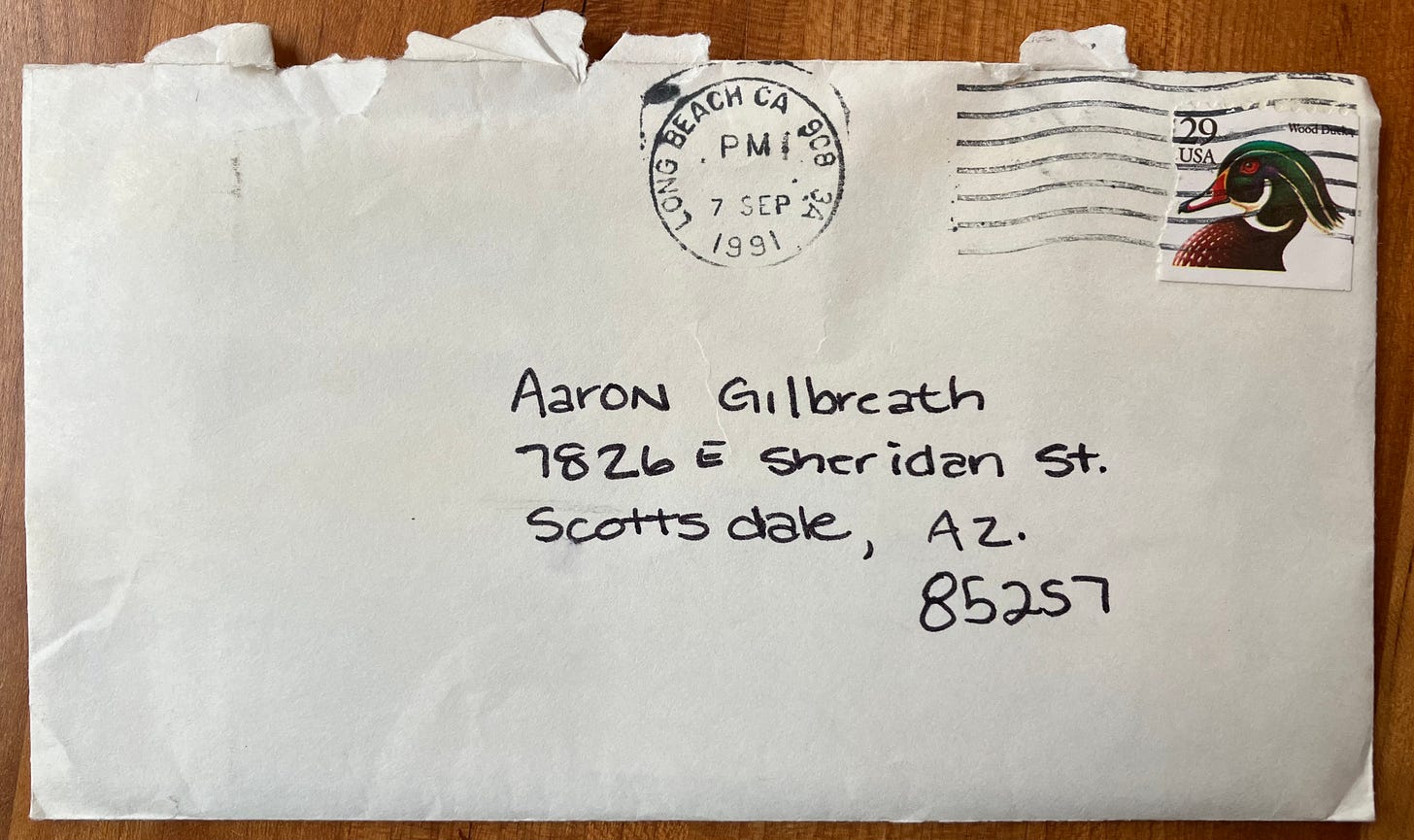

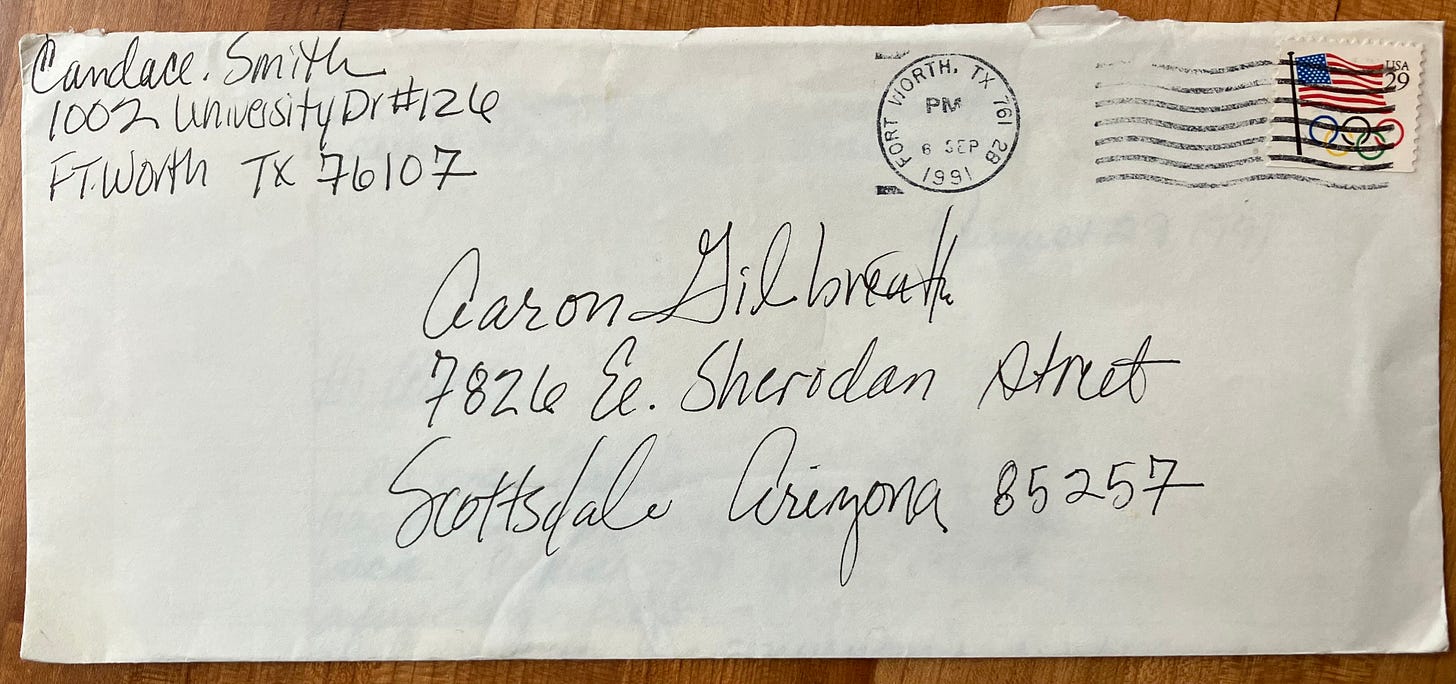

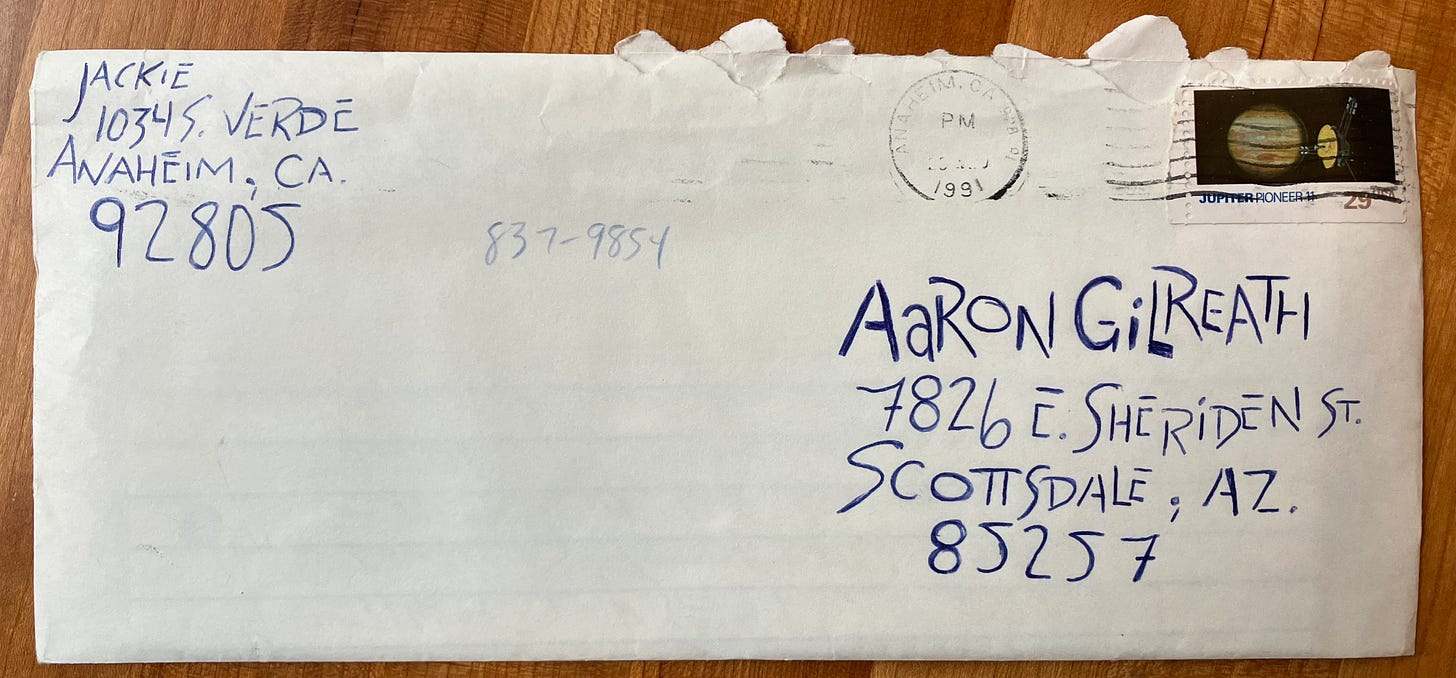

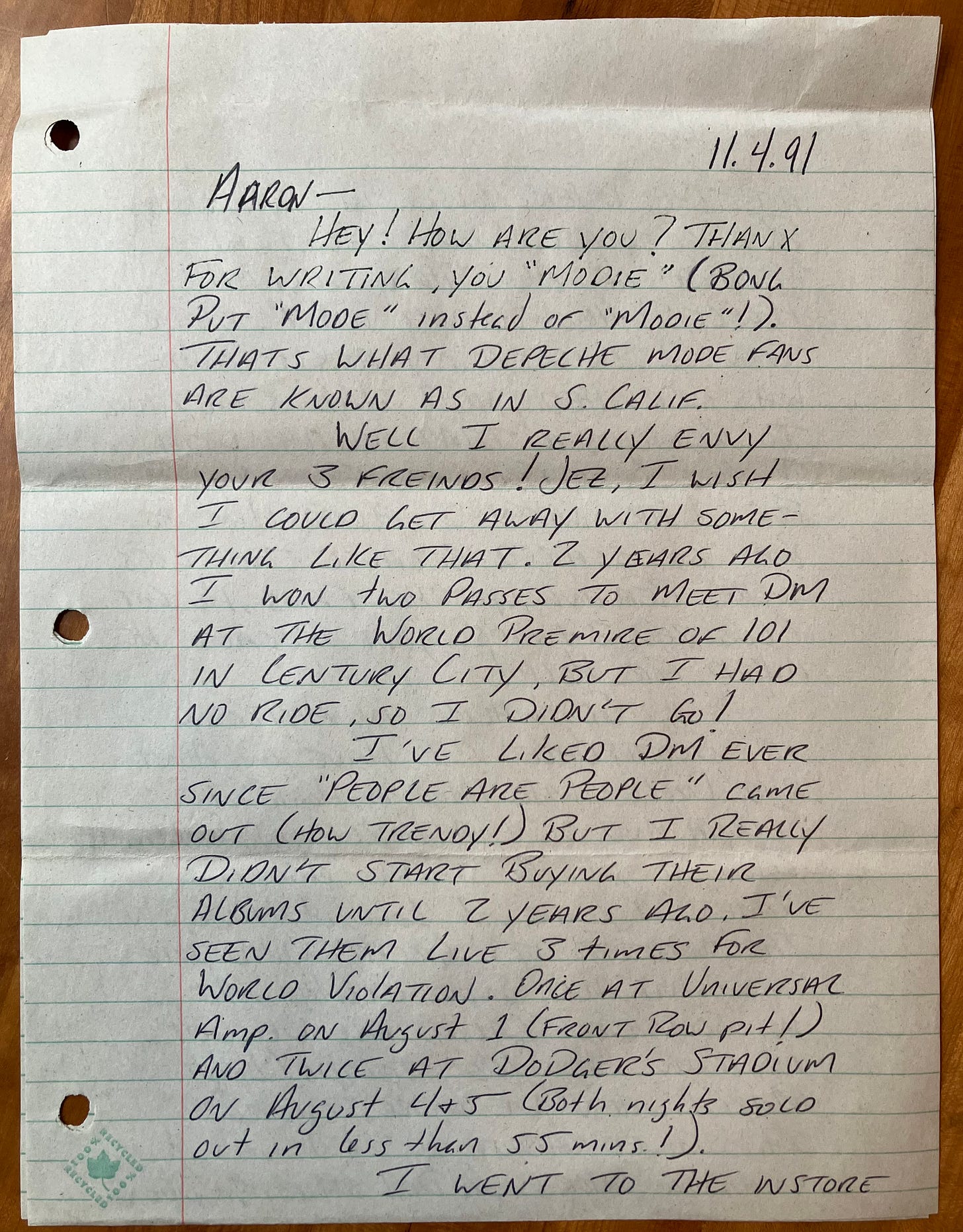

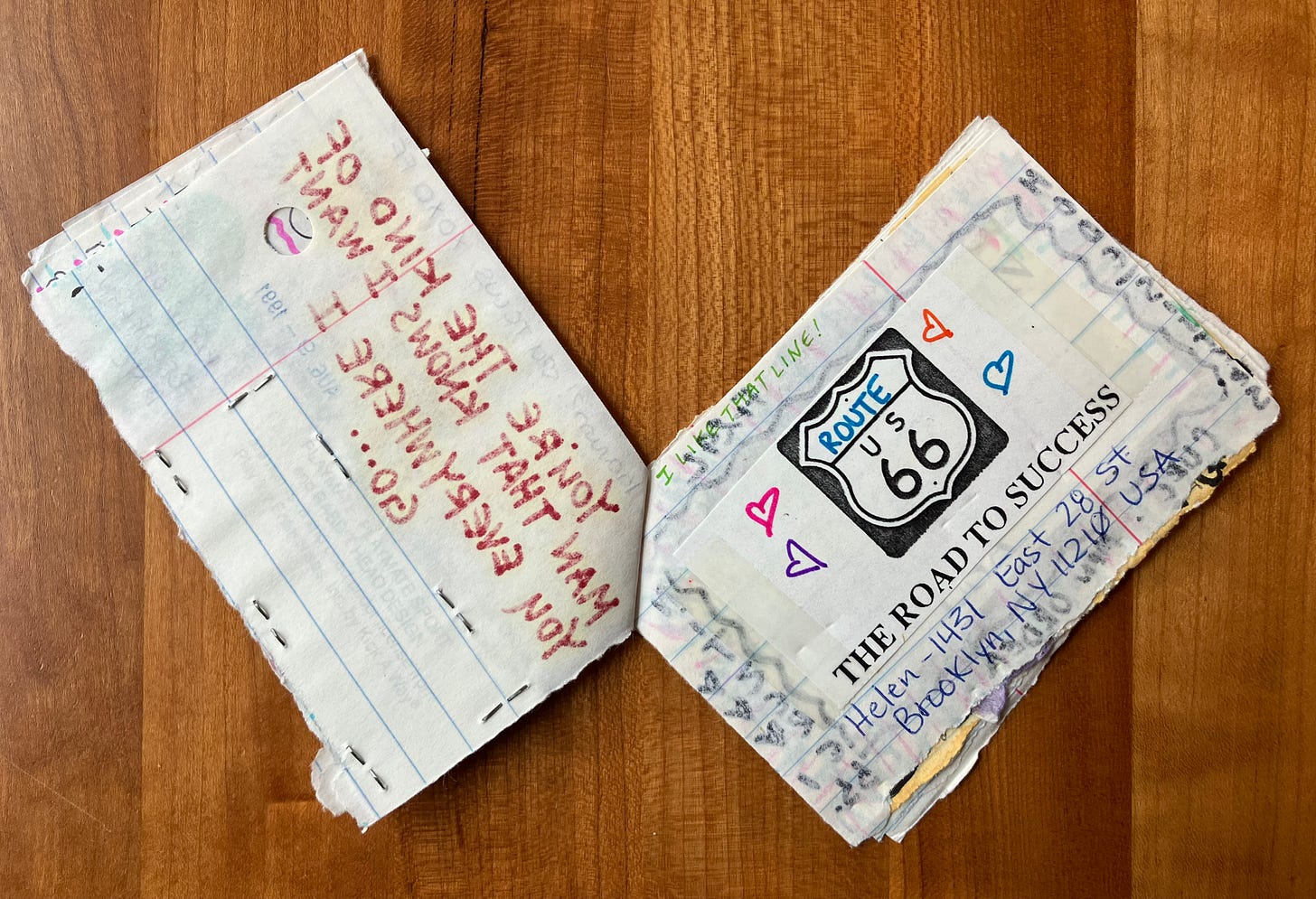

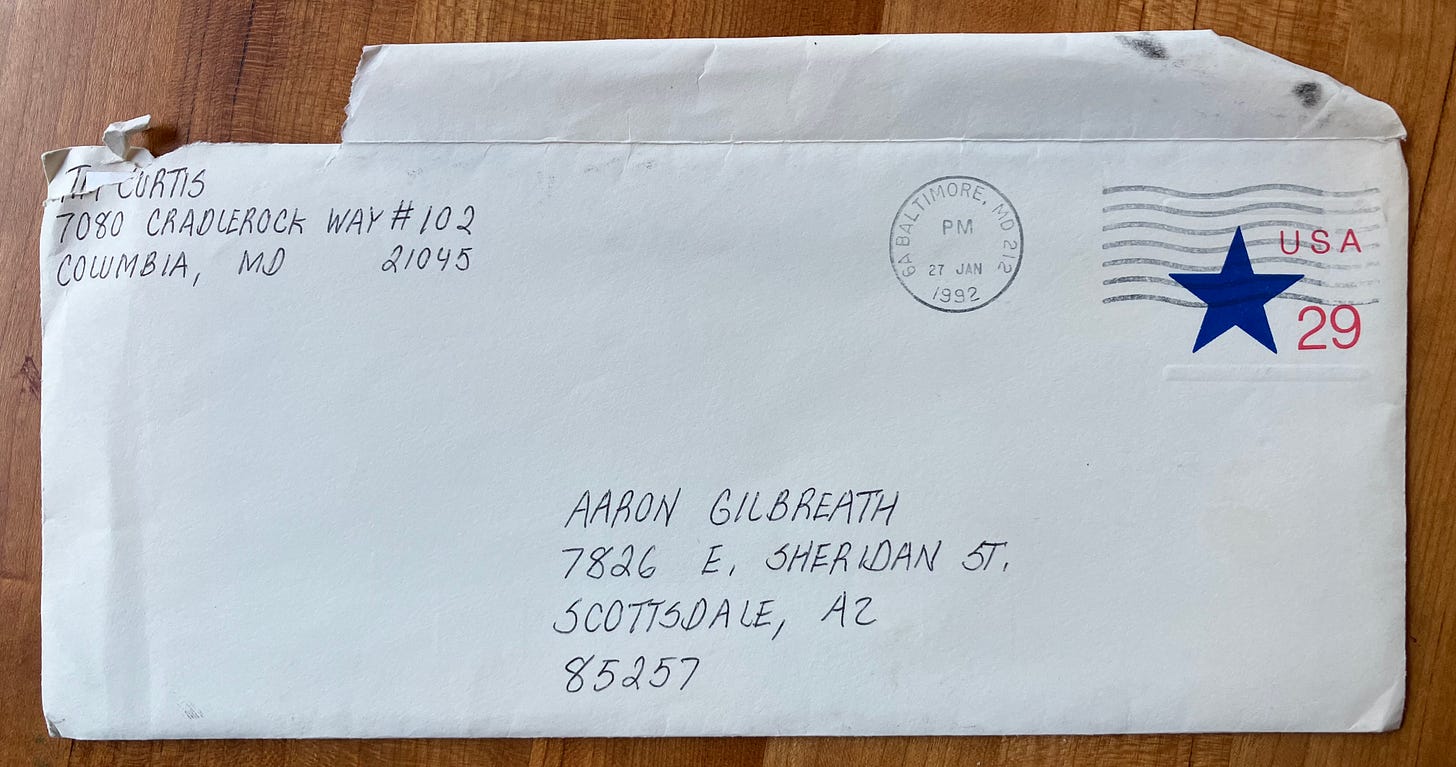

To get people writing to me in 1991, I also put a paid advertisement in the printed newsletter of the U.S. Depeche Mode fan club, called Bong for some reason. I said something about my search for particular live recordings and songs.

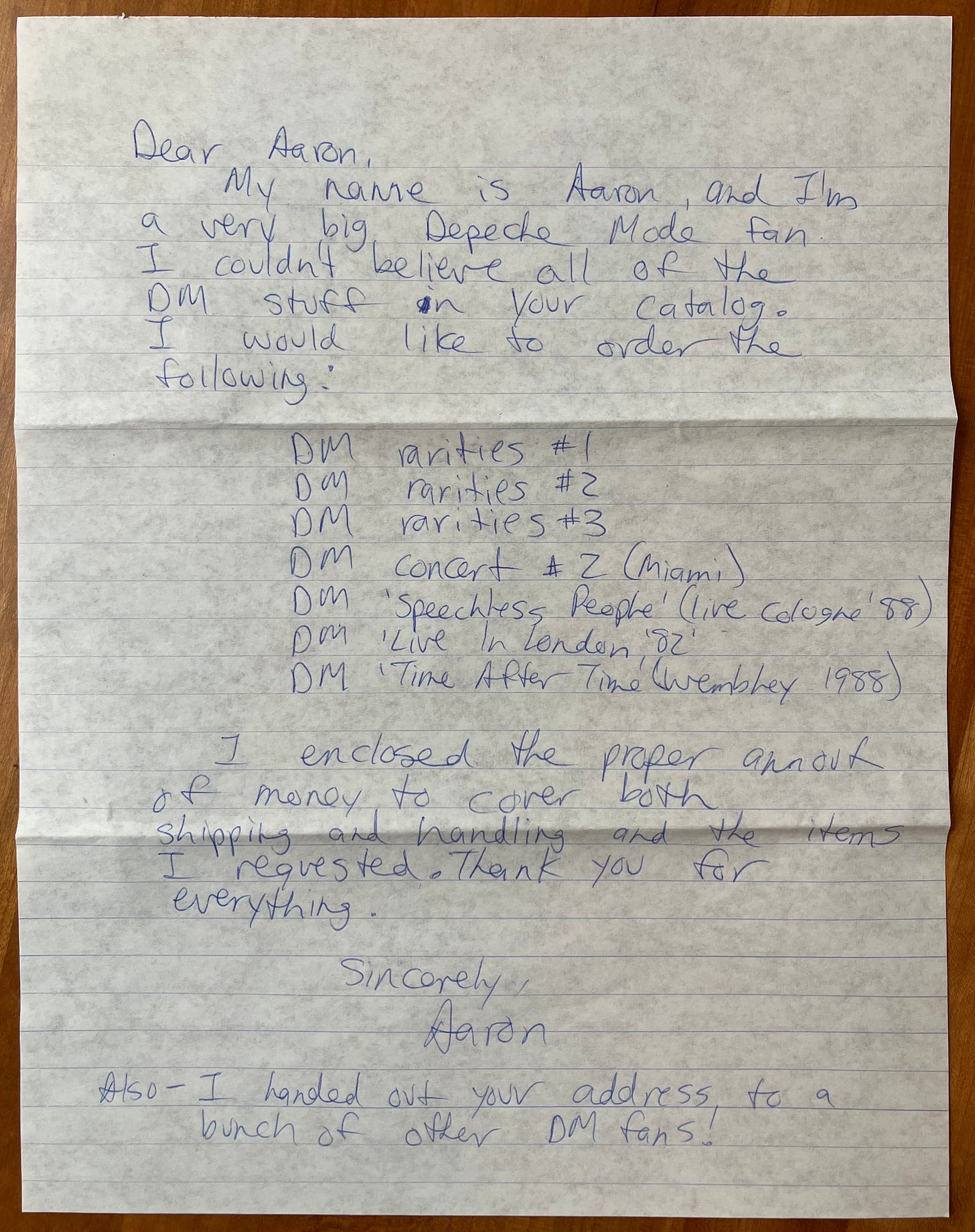

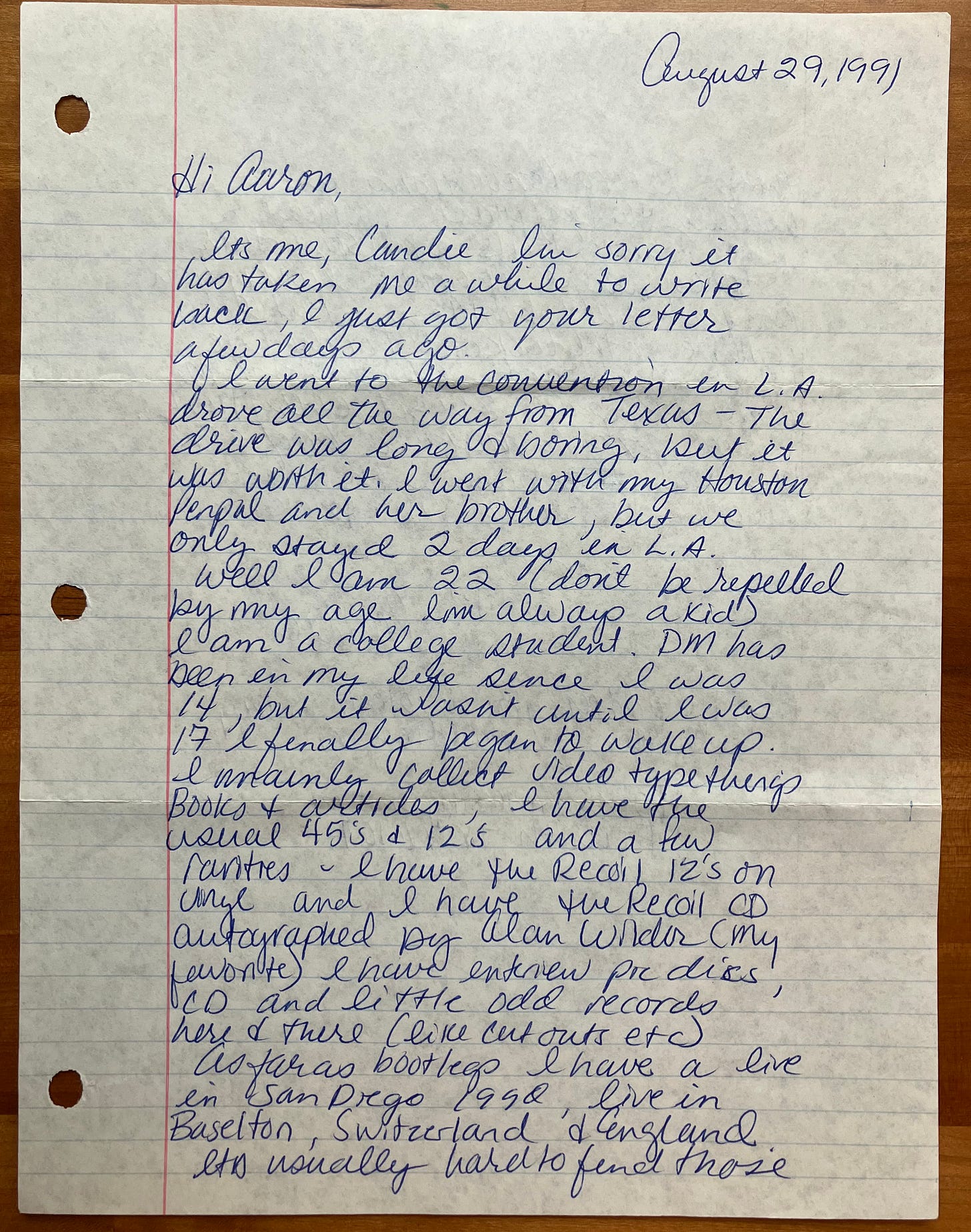

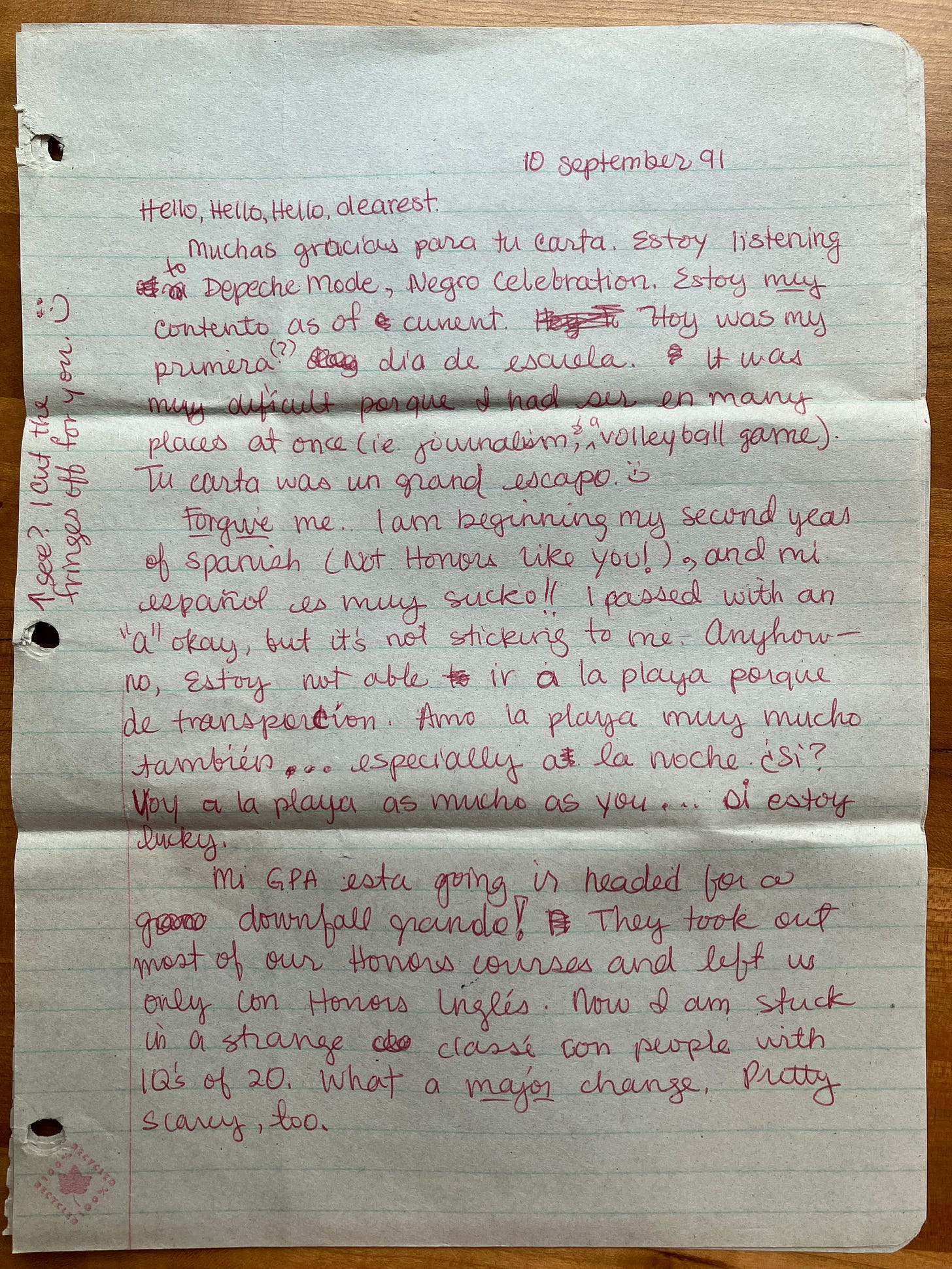

Fans read it. Letters quickly started arriving.

Some offered recordings. Some could only offer to let me know if they found those recordings or met anyone else who may know where to find them. That’s how this worked before internet!

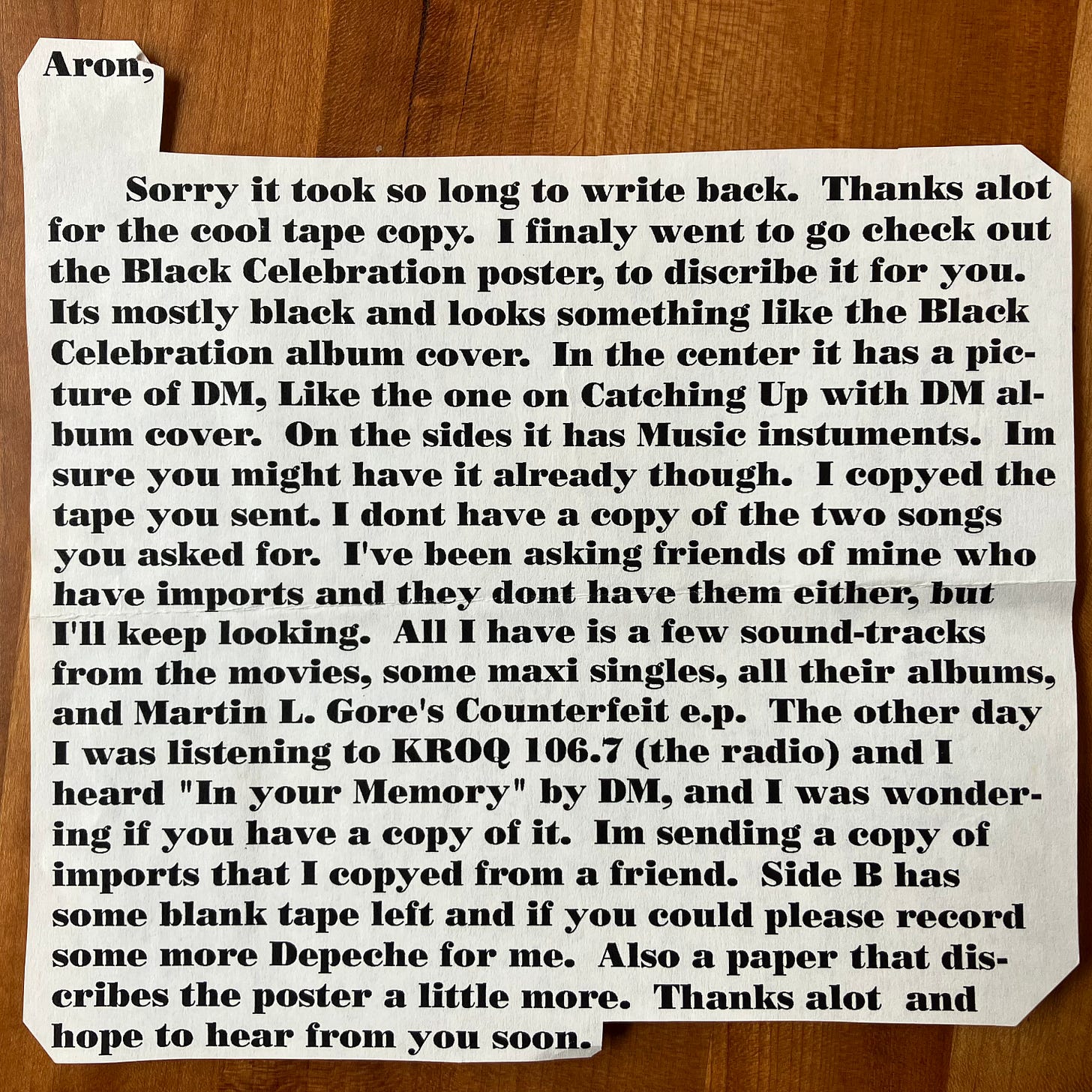

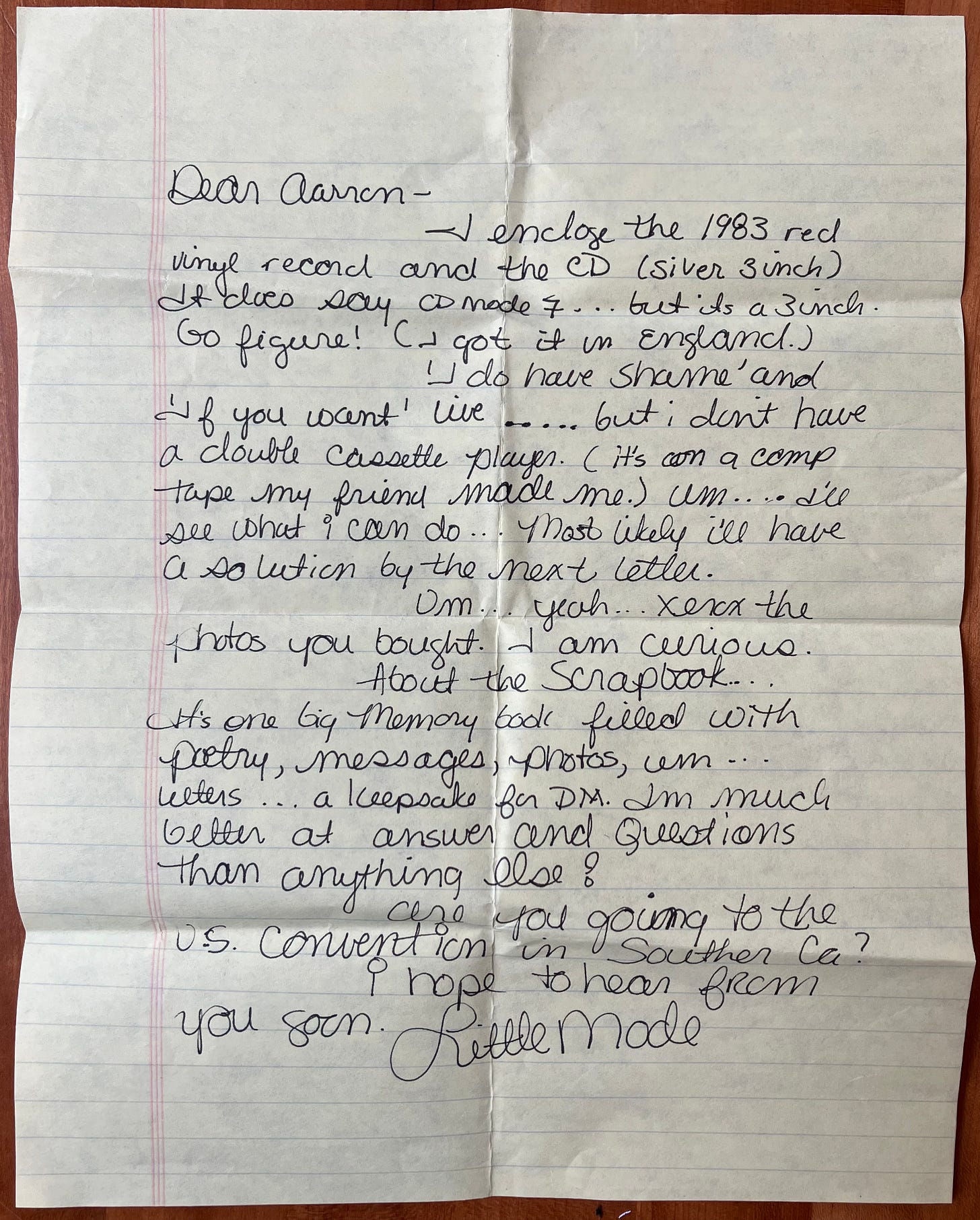

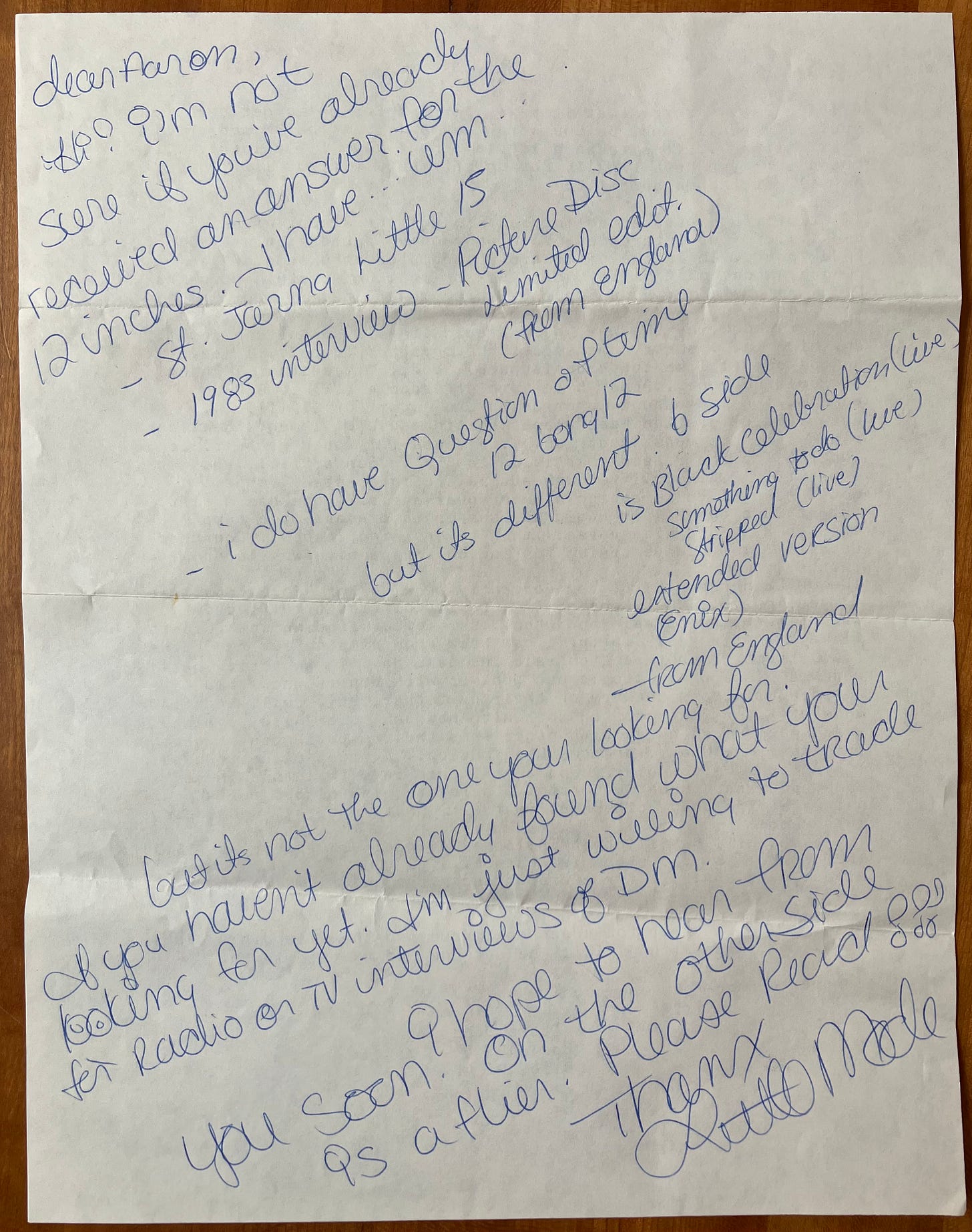

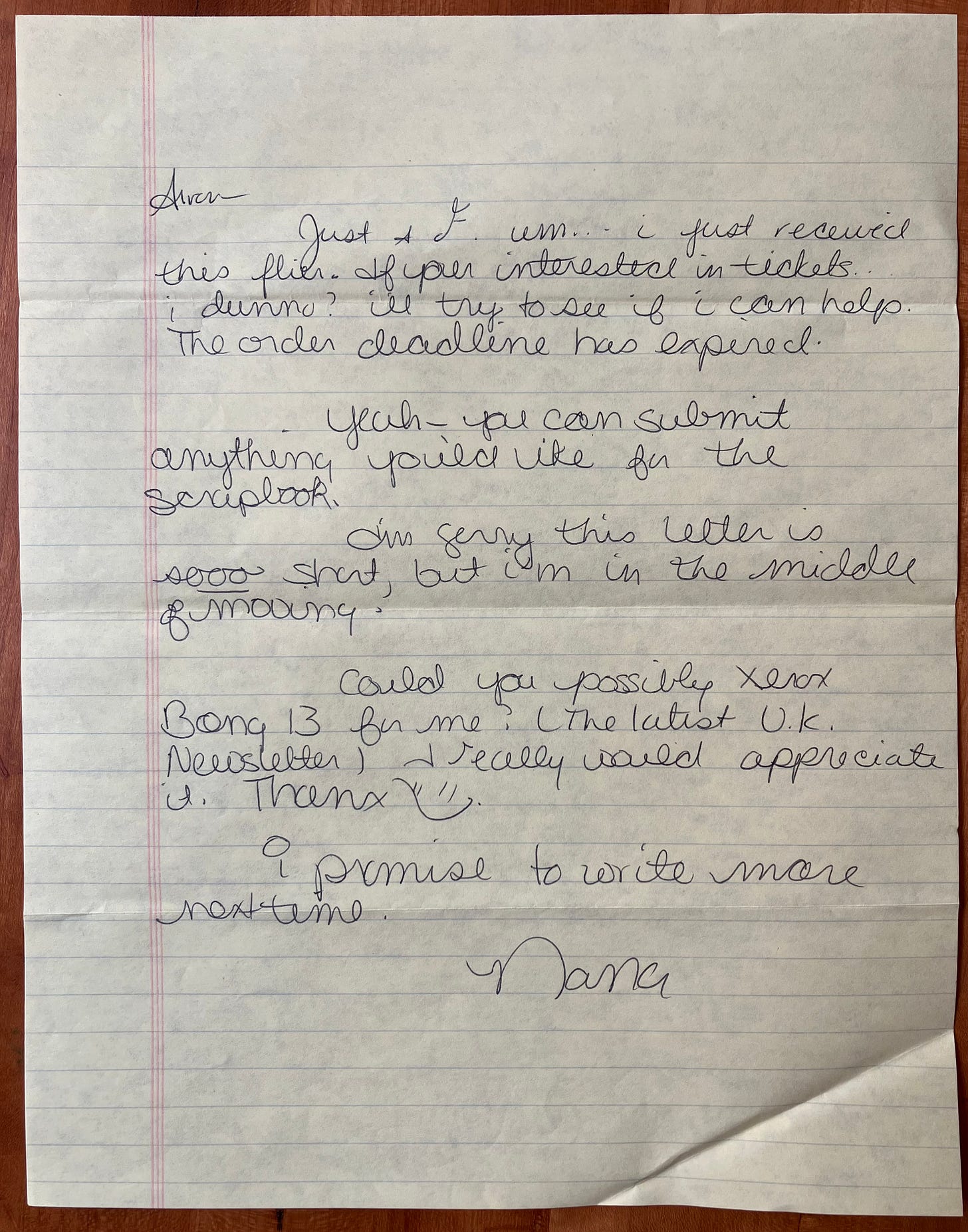

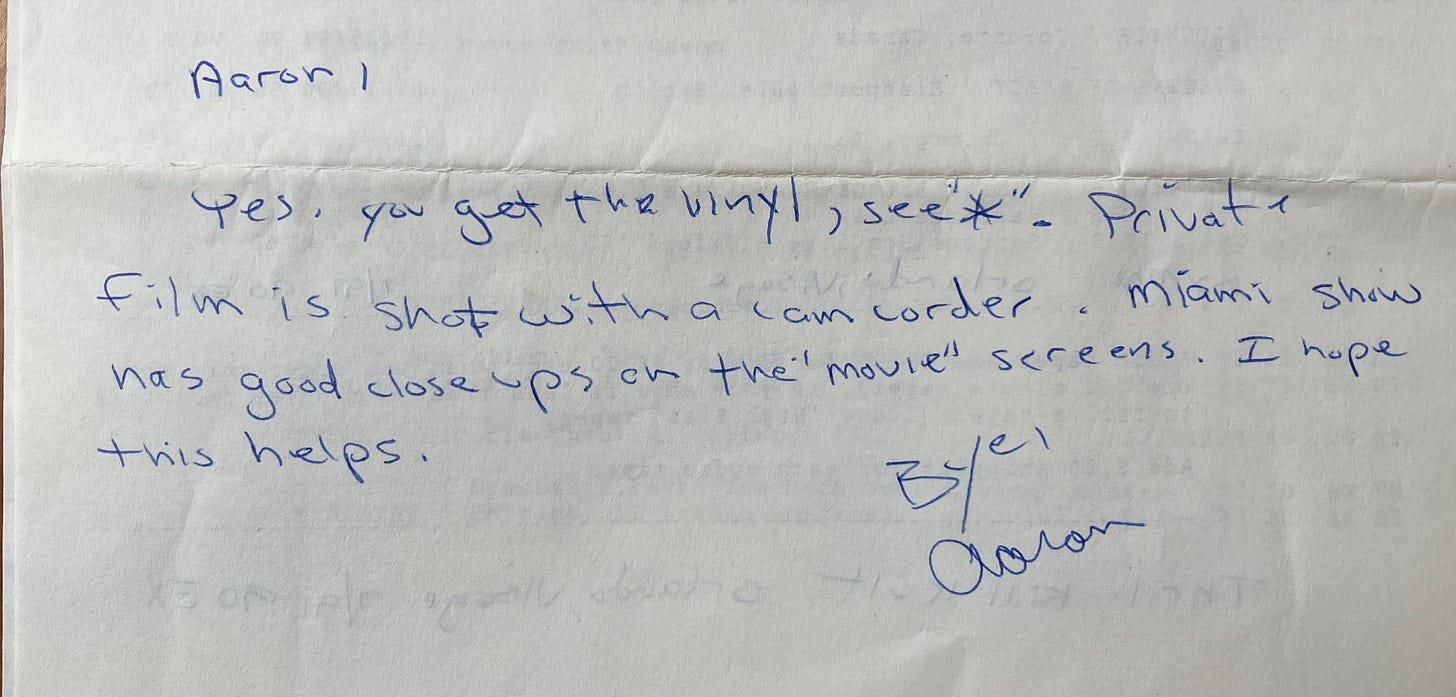

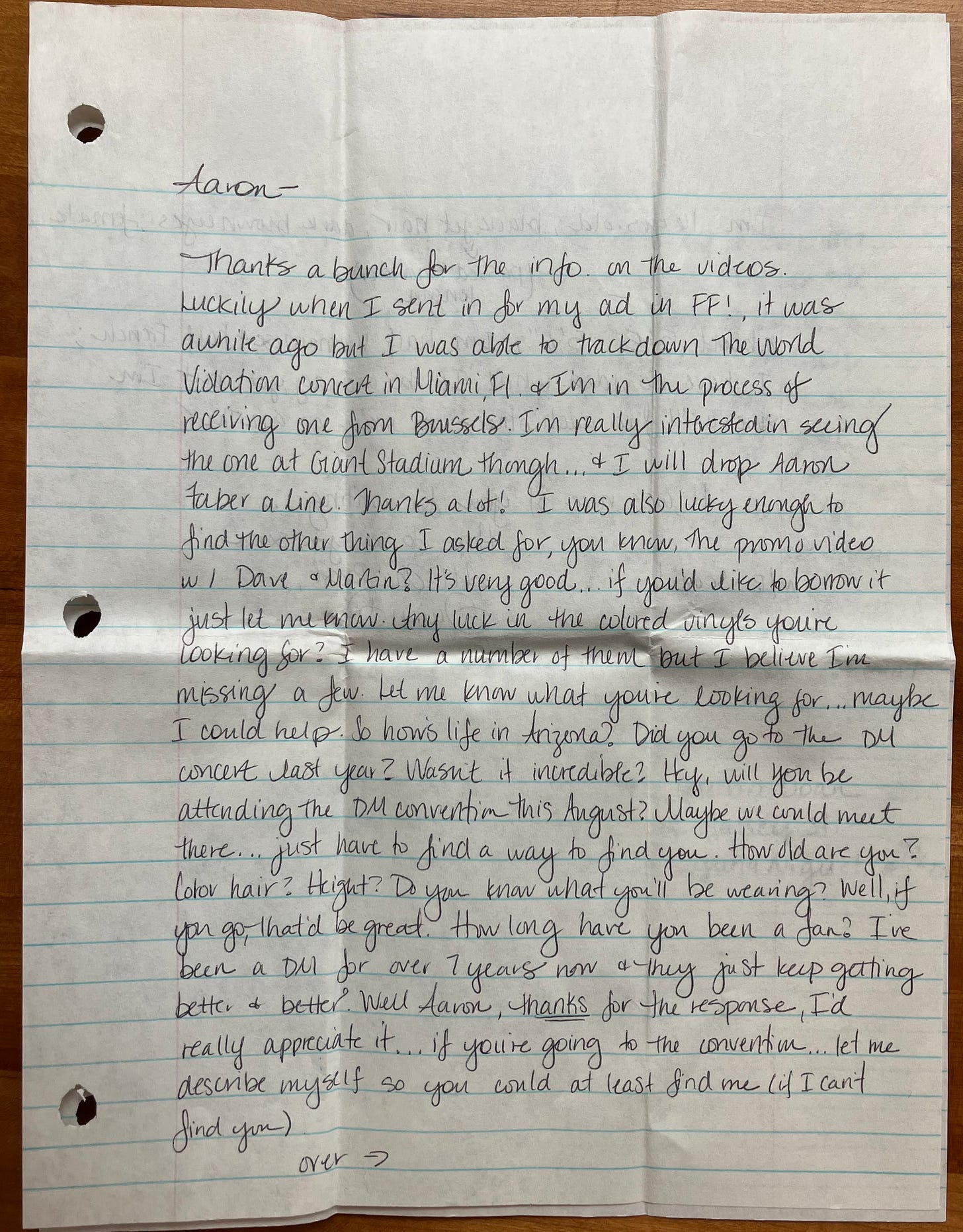

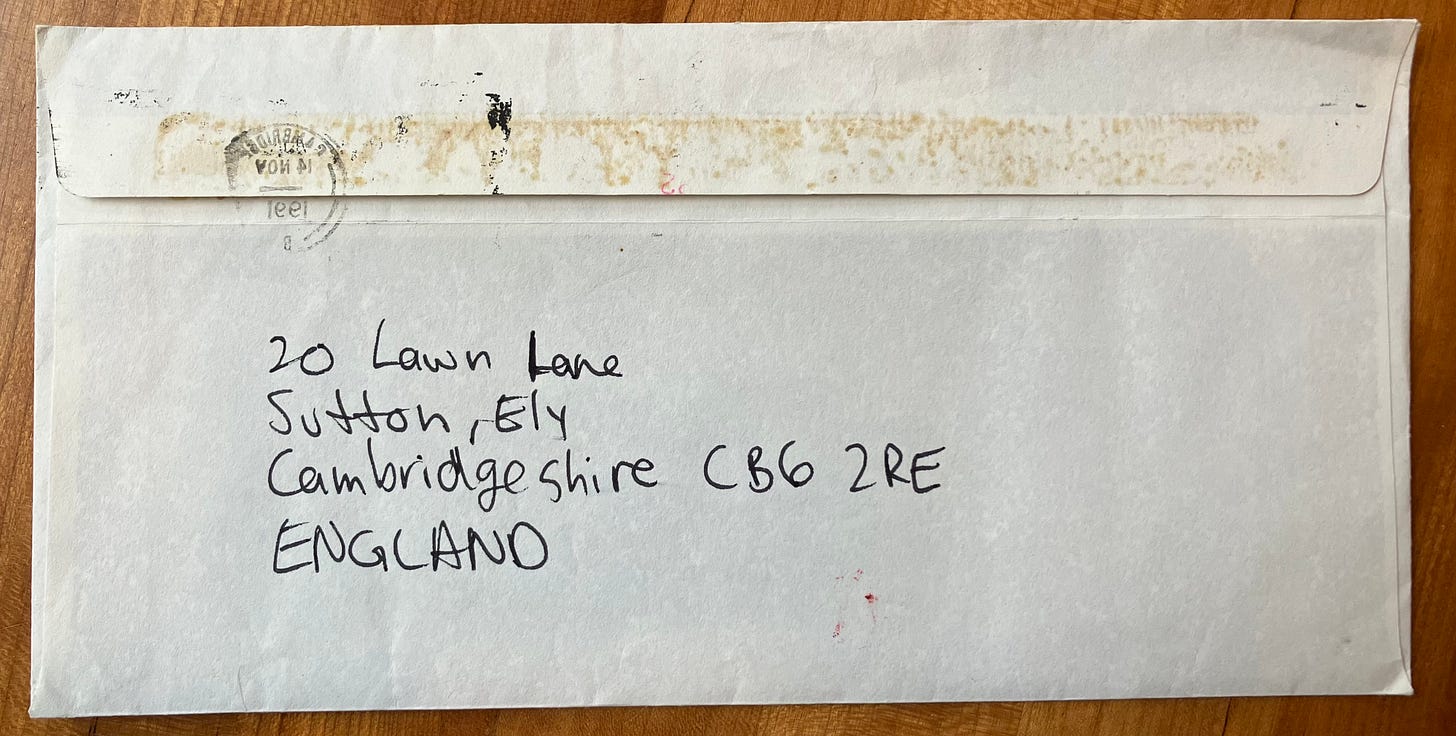

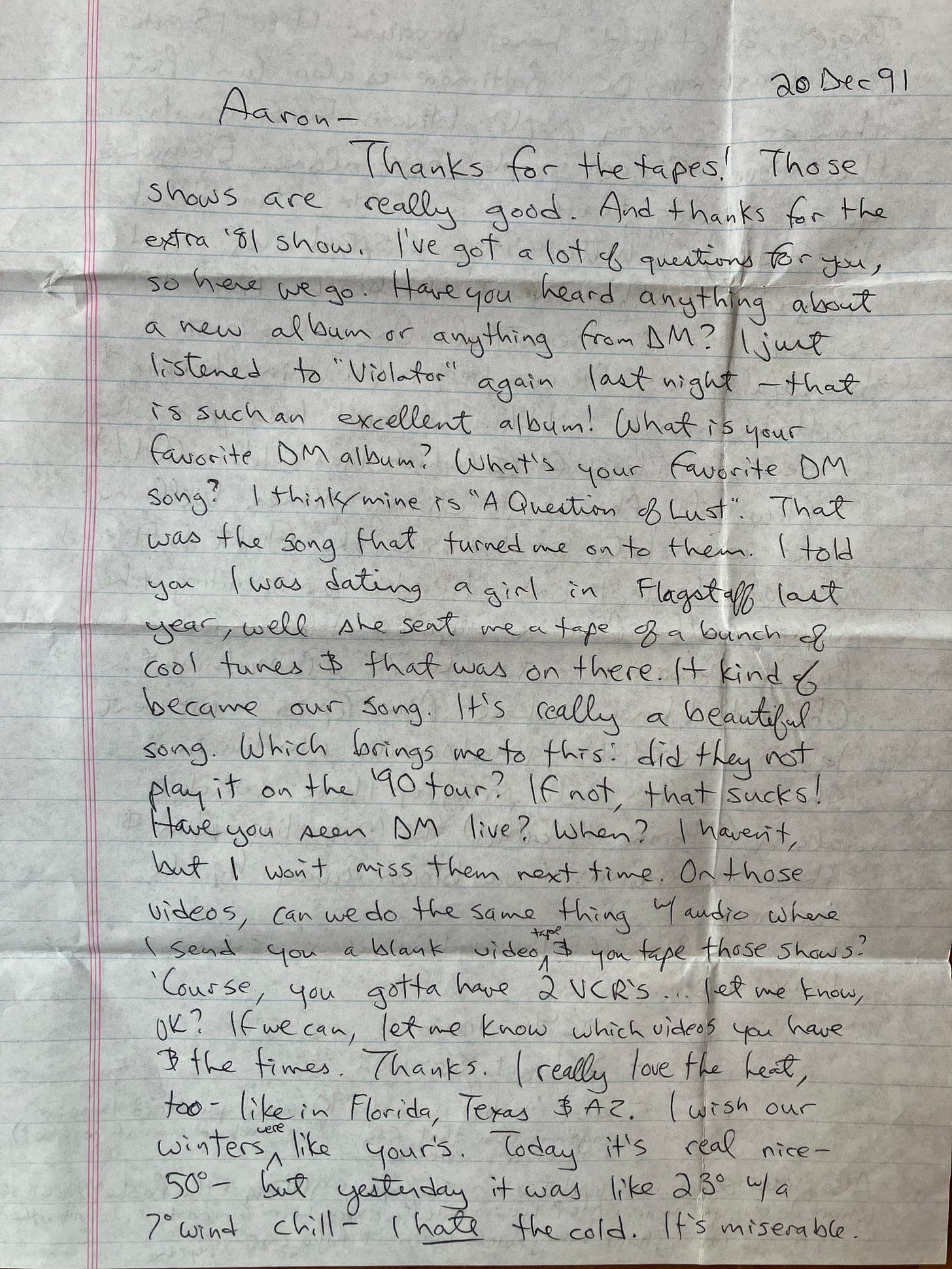

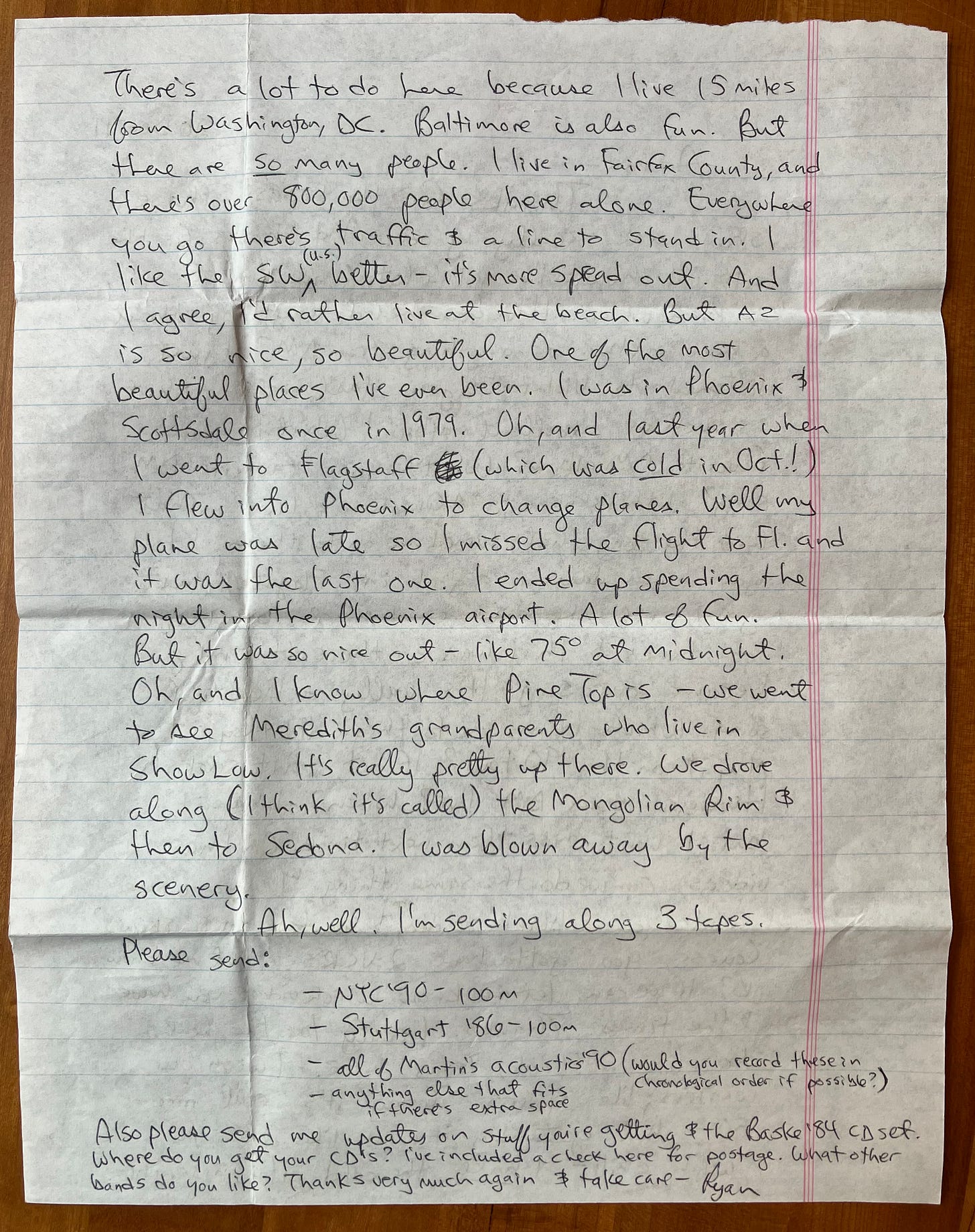

Once I had pen pals, we traded.

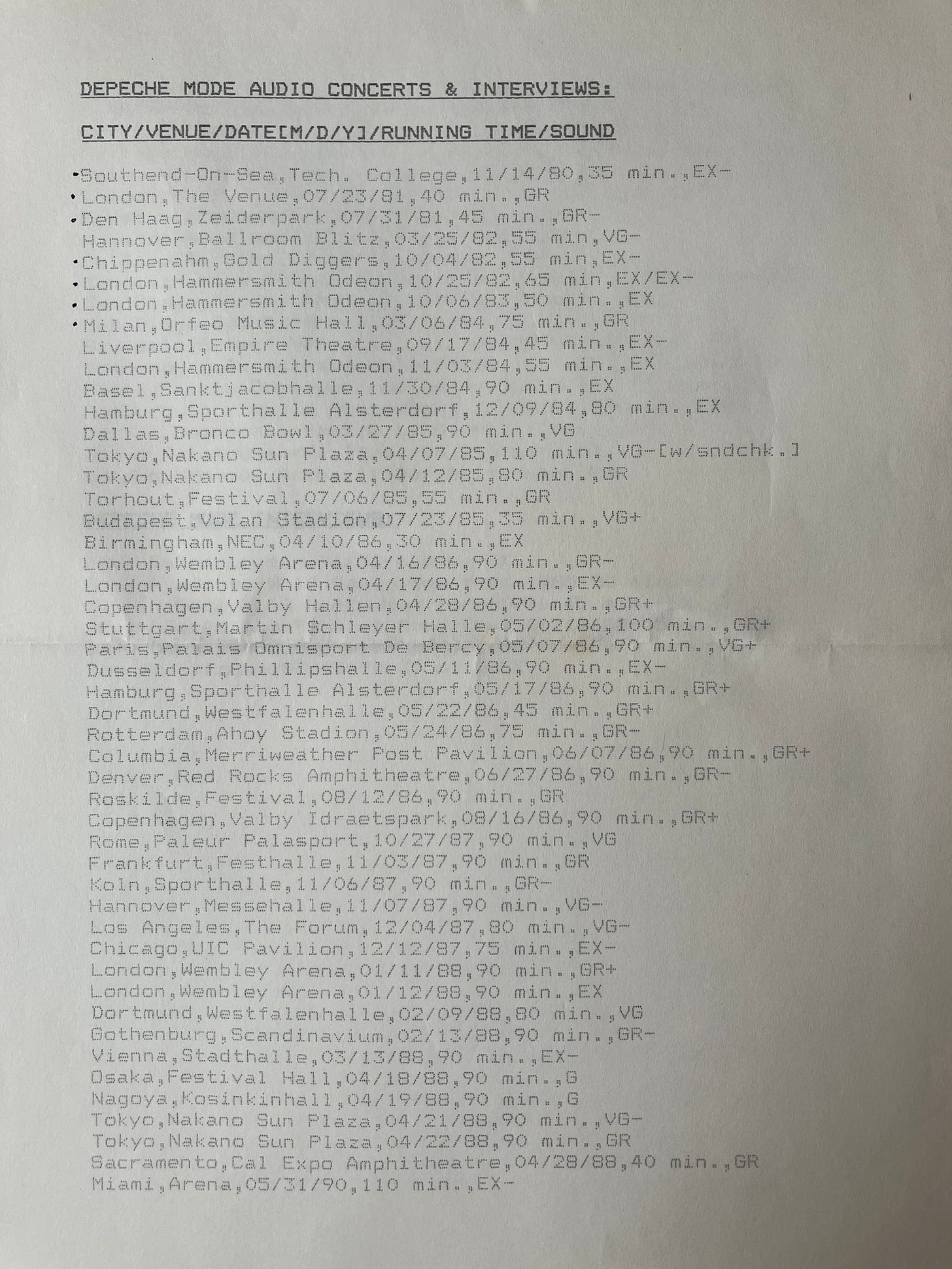

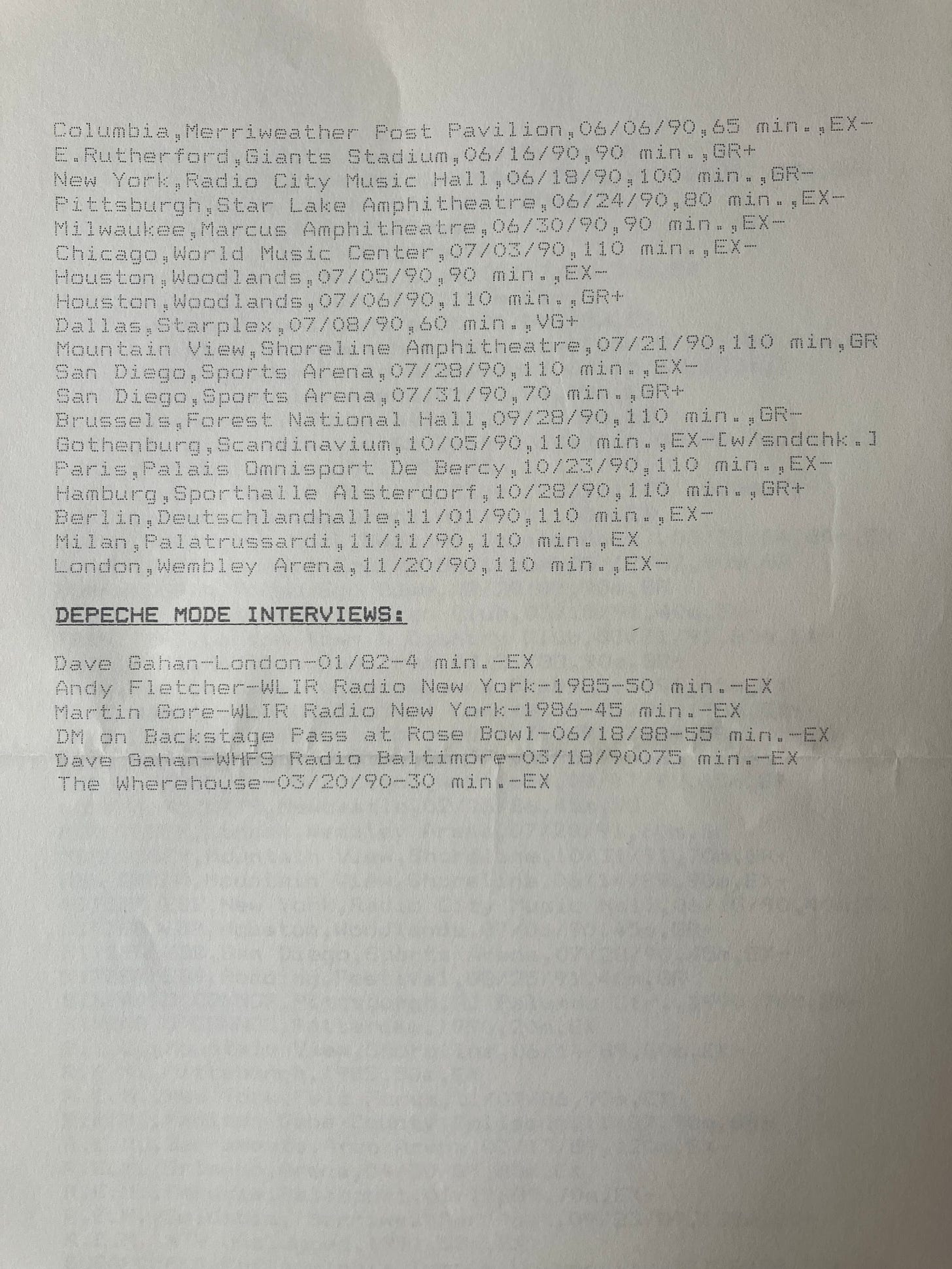

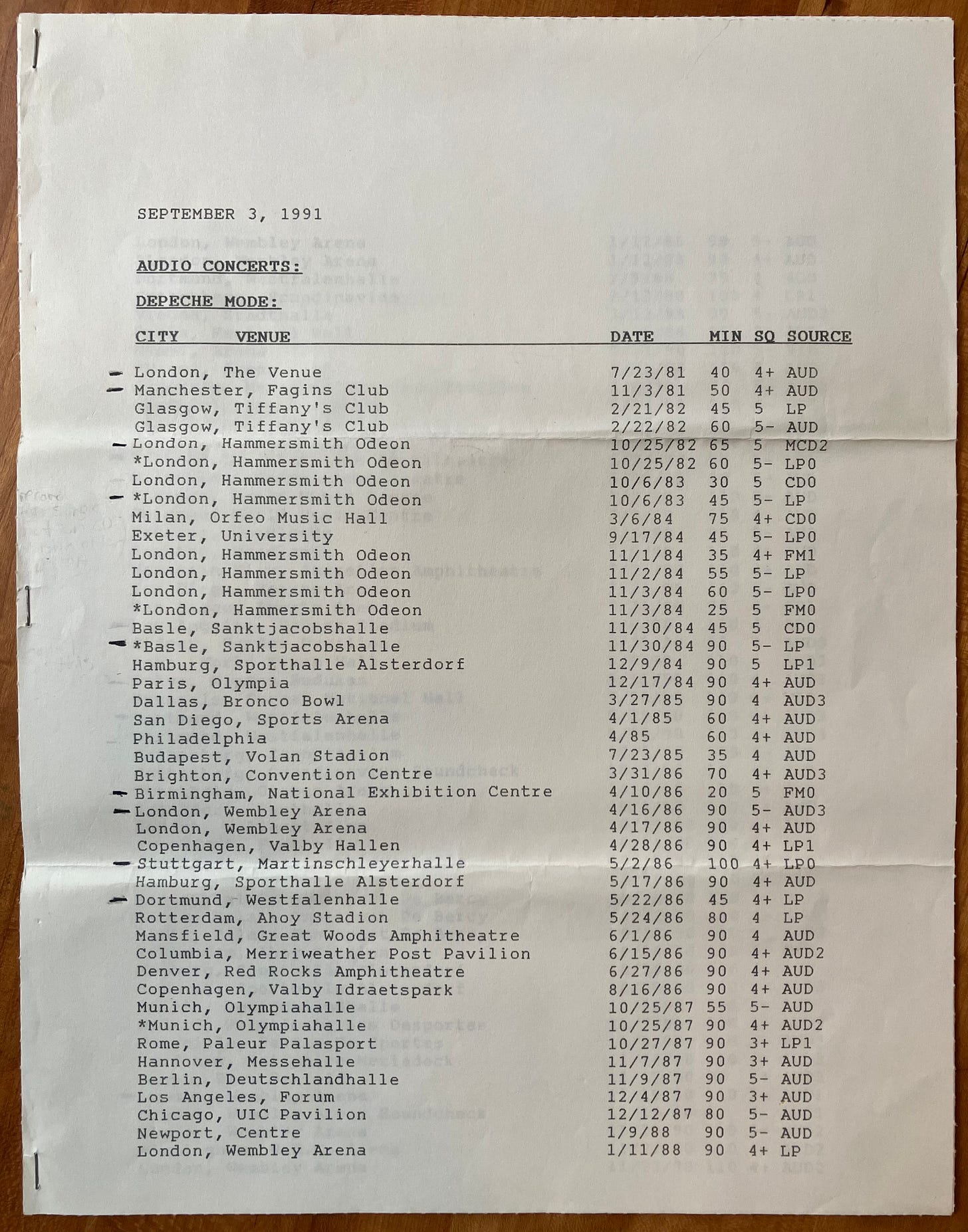

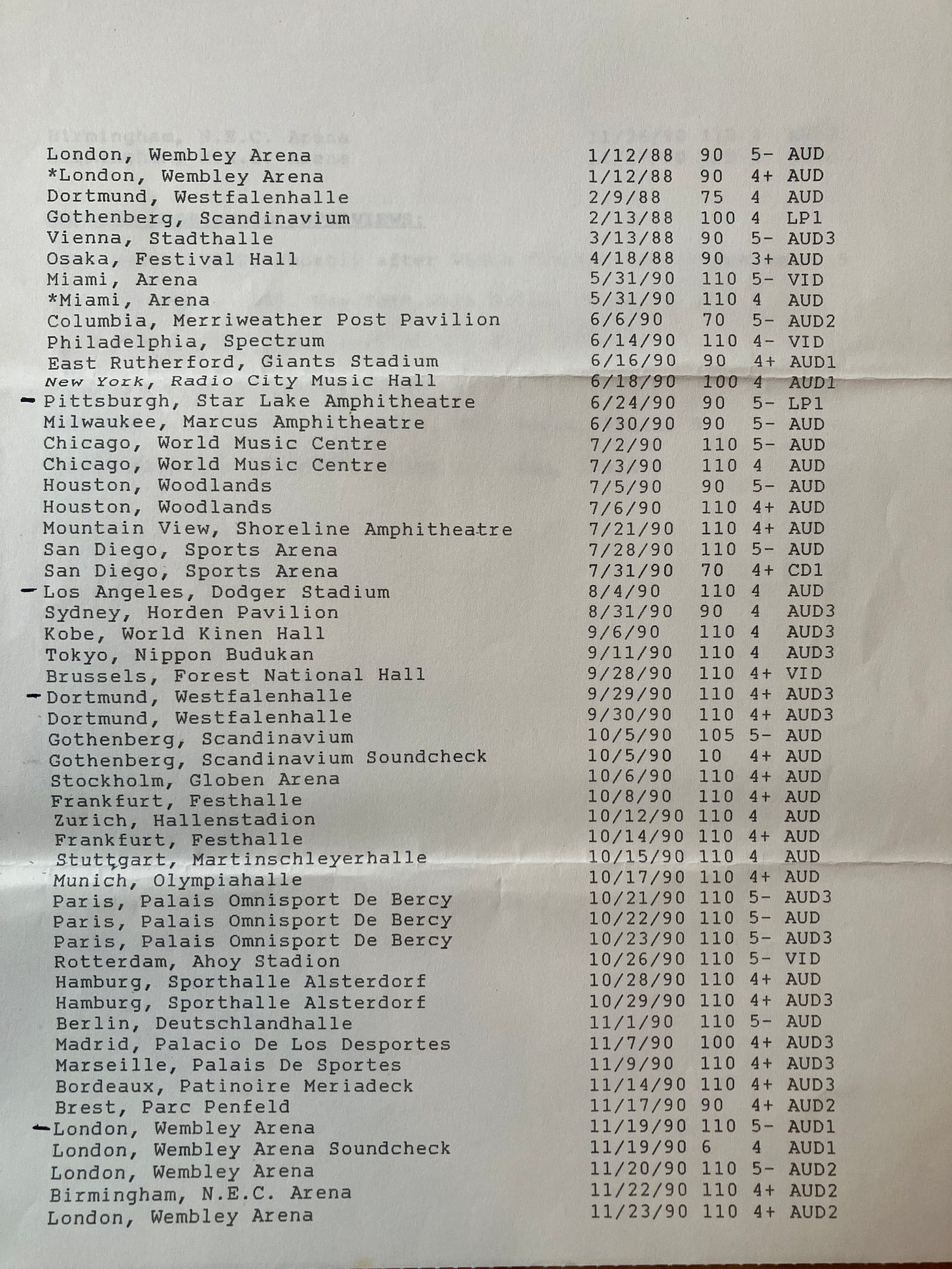

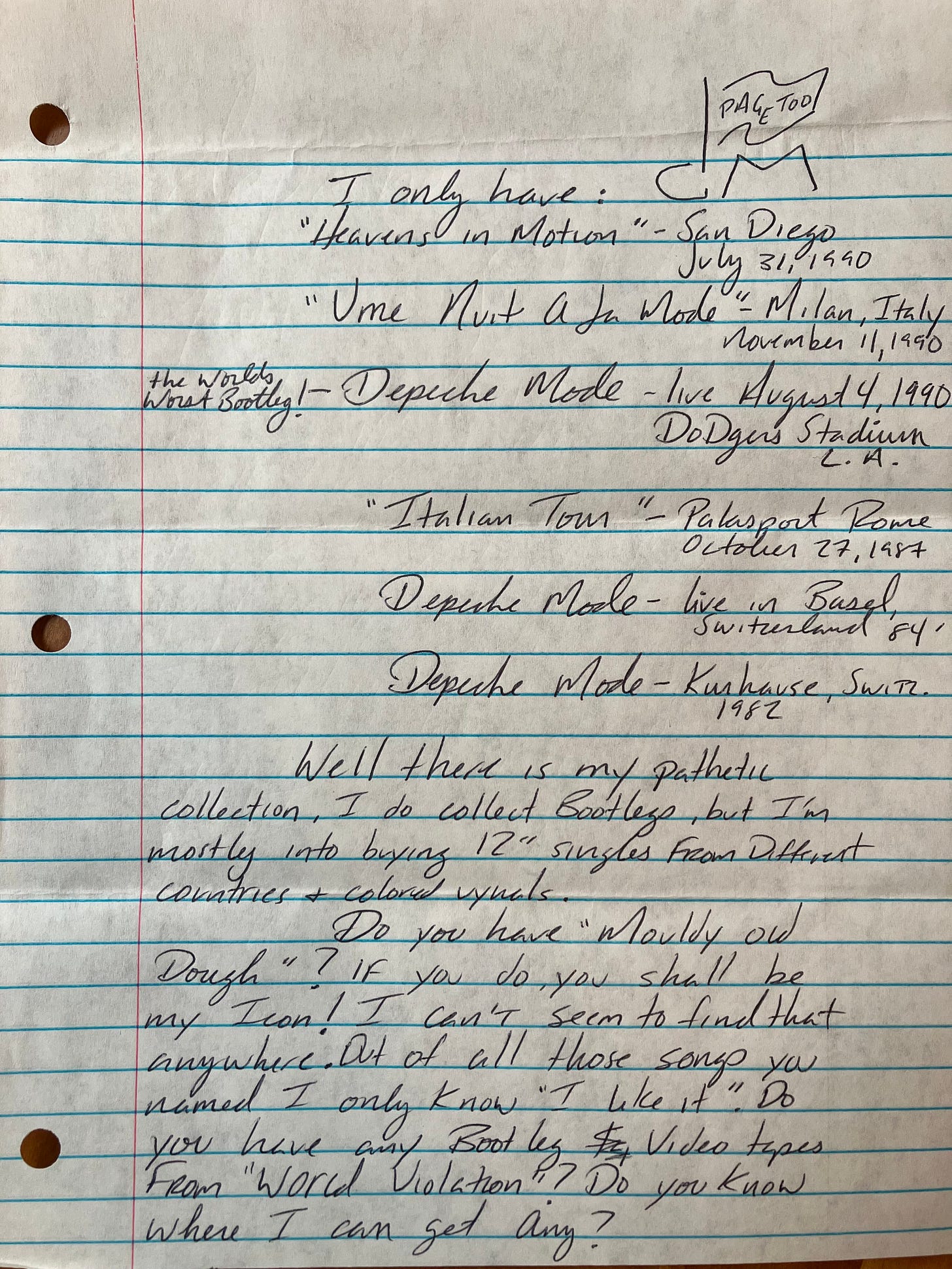

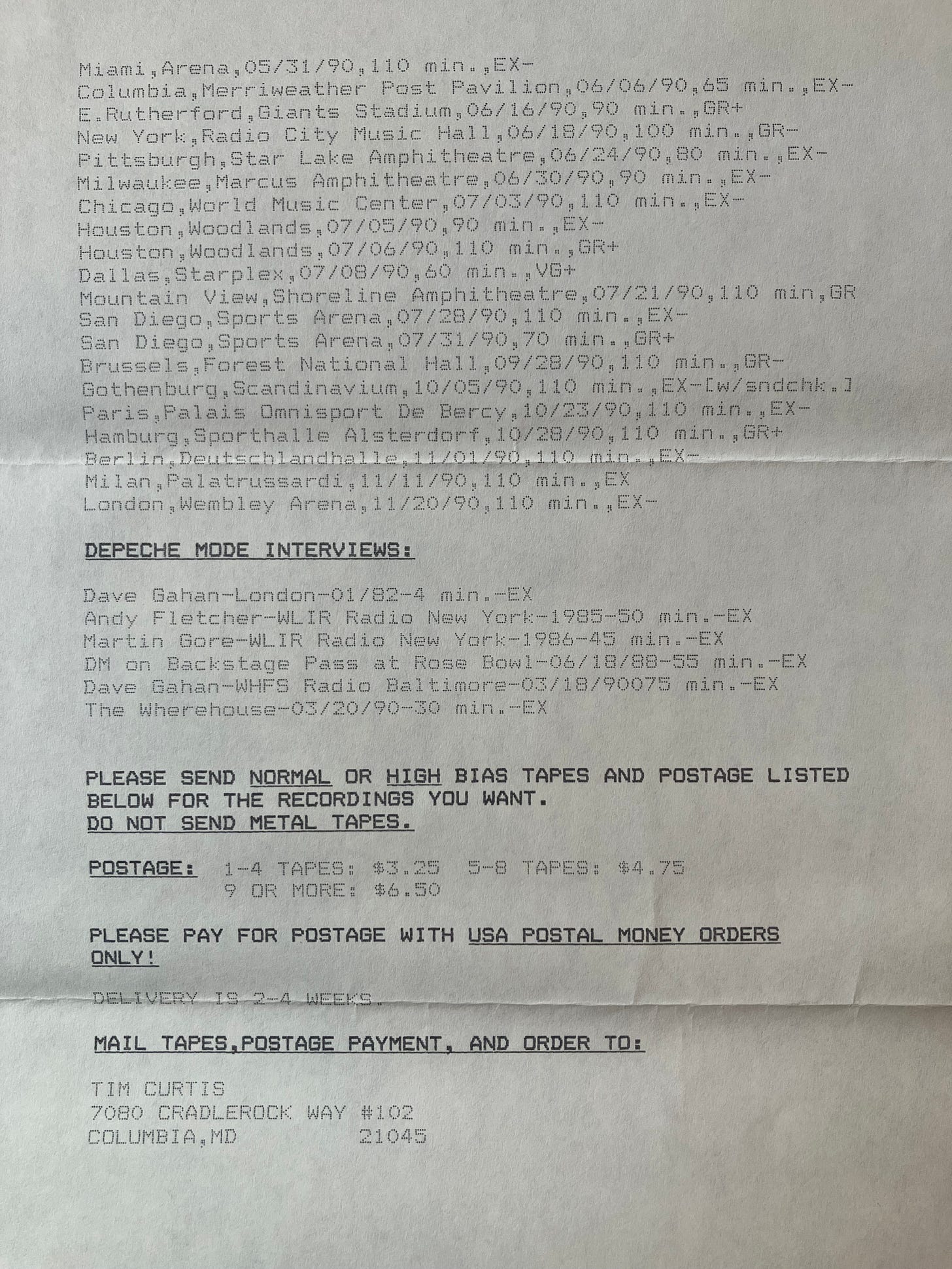

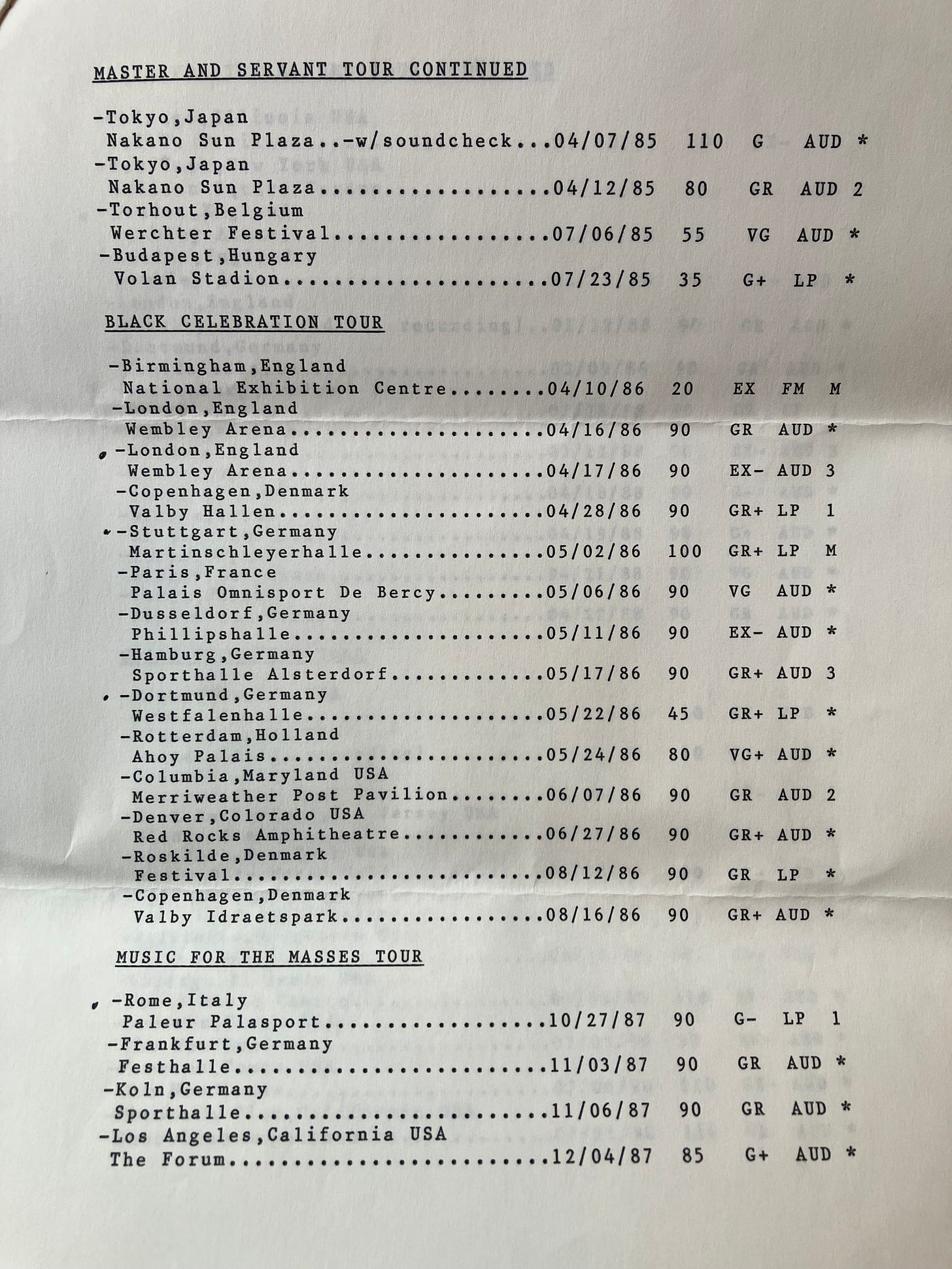

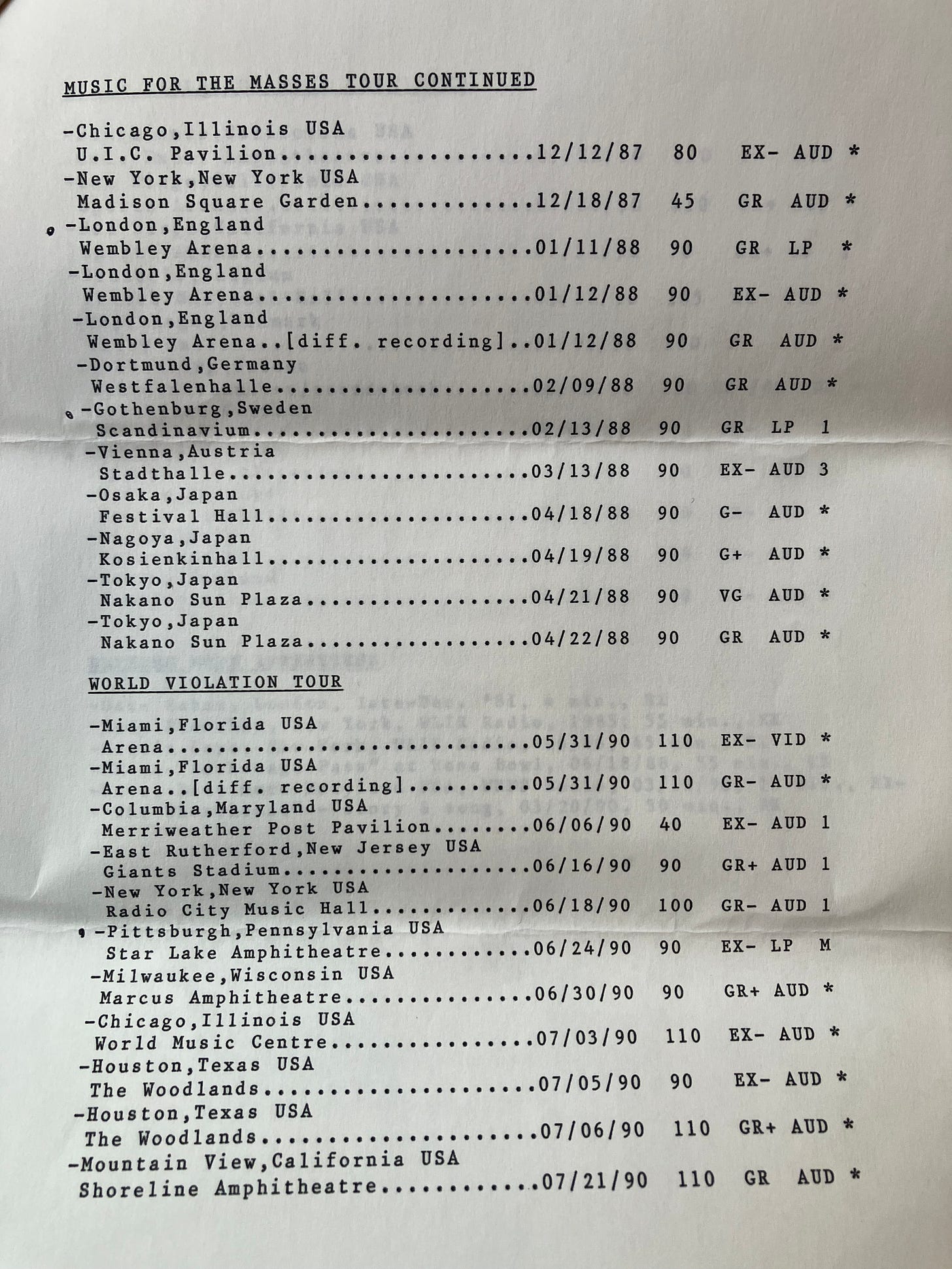

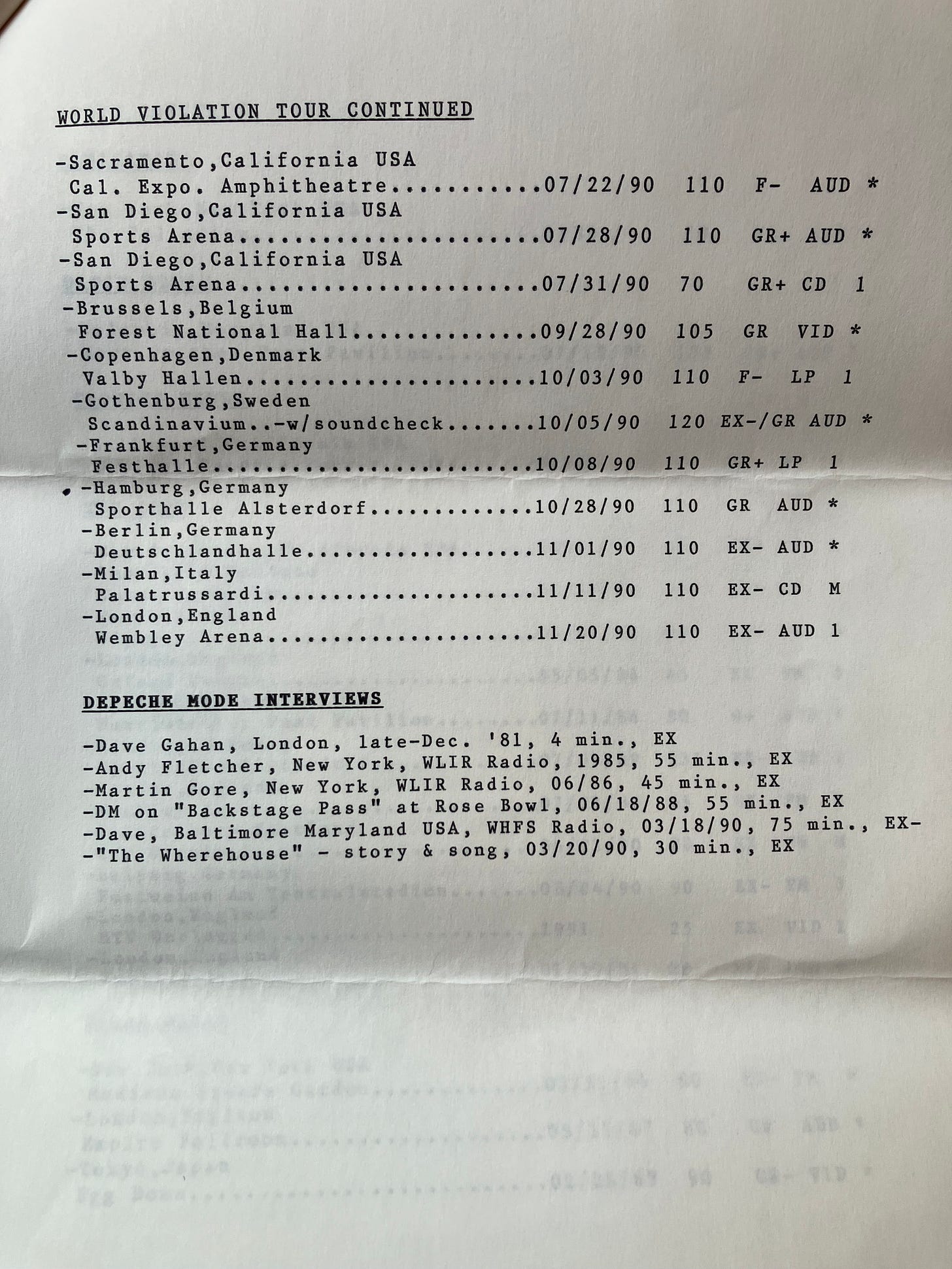

This went on for a little over a year. I’d write letters. Fellow fans would send these lists of shows they had recordings of and/or shows they wanted.

Trading required leverage. Some fans would freely give you recordings you desperately wanted, because they related to your desperation and hoped others would take similar pity on them. Other fans required I use whatever magazine articles, tapes, or band interviews I had as currency, and my pen pals would sometimes send recordings of cool rare stuff.

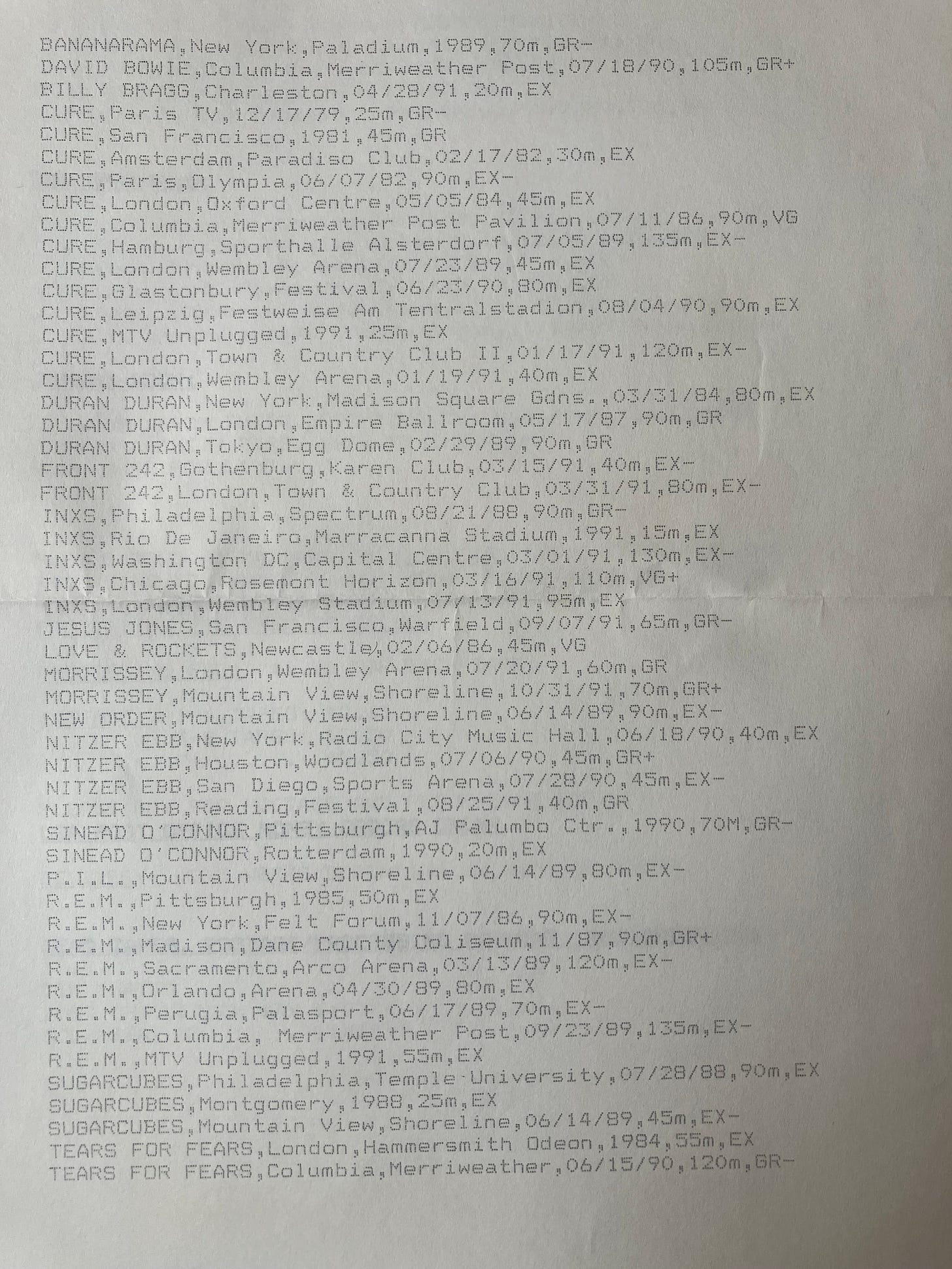

I often made covers for them.

The effort was worth it.

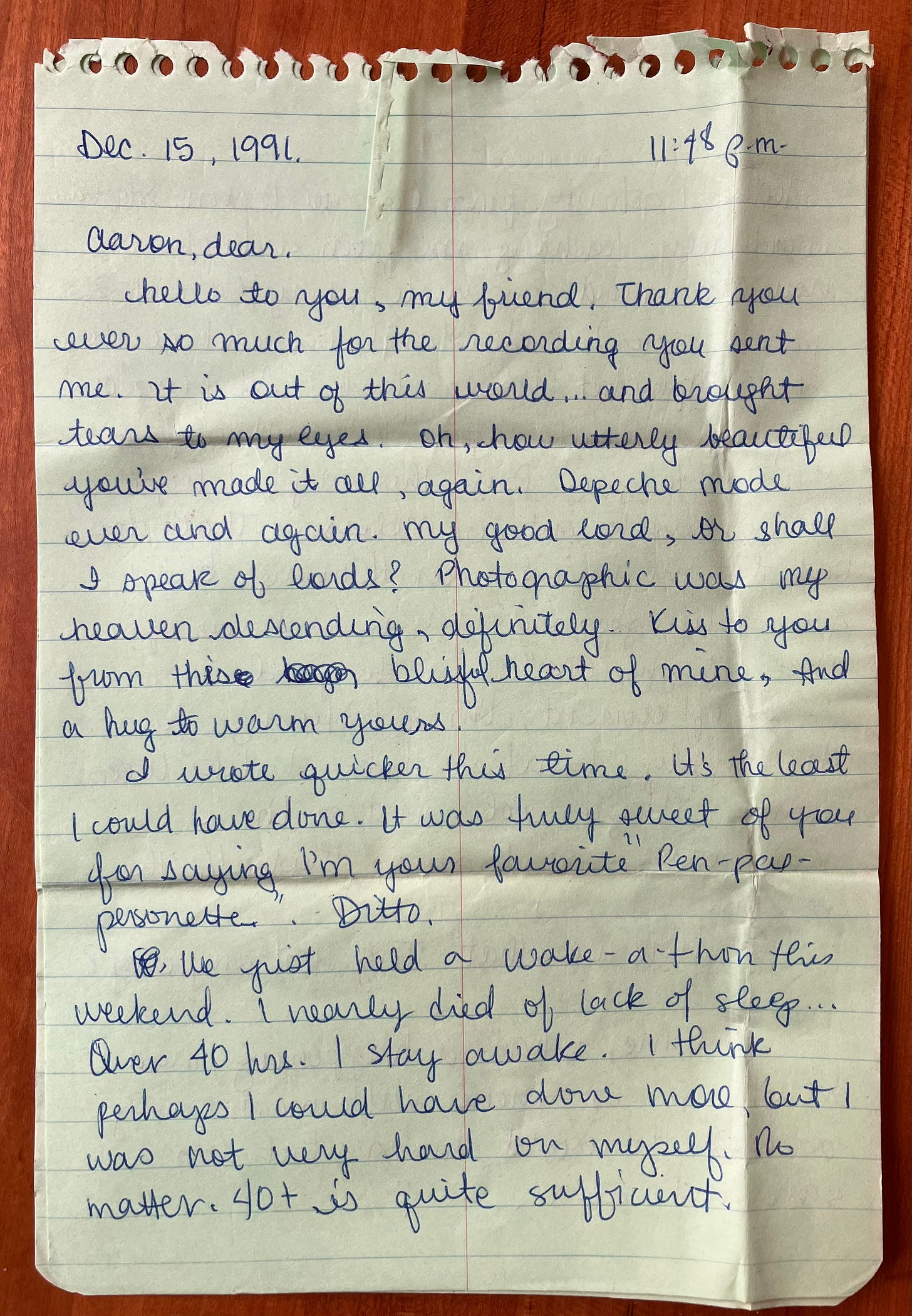

The live version of “Photographic” from DM’s highly bootlegged 1984 Hamburg concert struck me as one of the most stirring songs I’d heard. First a faint electronic twittering moved back and forth between speakers. The deep thump of the base drum hit—doomp, doomp, doomp, doomp—before Dave sang: “A white house, a white room, the program of today.” I didn’t know what the hell he was singing about, but I sang with him. It wasn’t the lyrics that moved me so much as the layers of sound and harmonies where Martin lays his high voice atop Dave’s deep one. “And looking to the day,” they sing, “I mesmerize the light.” From then on, live recordings became my thing.

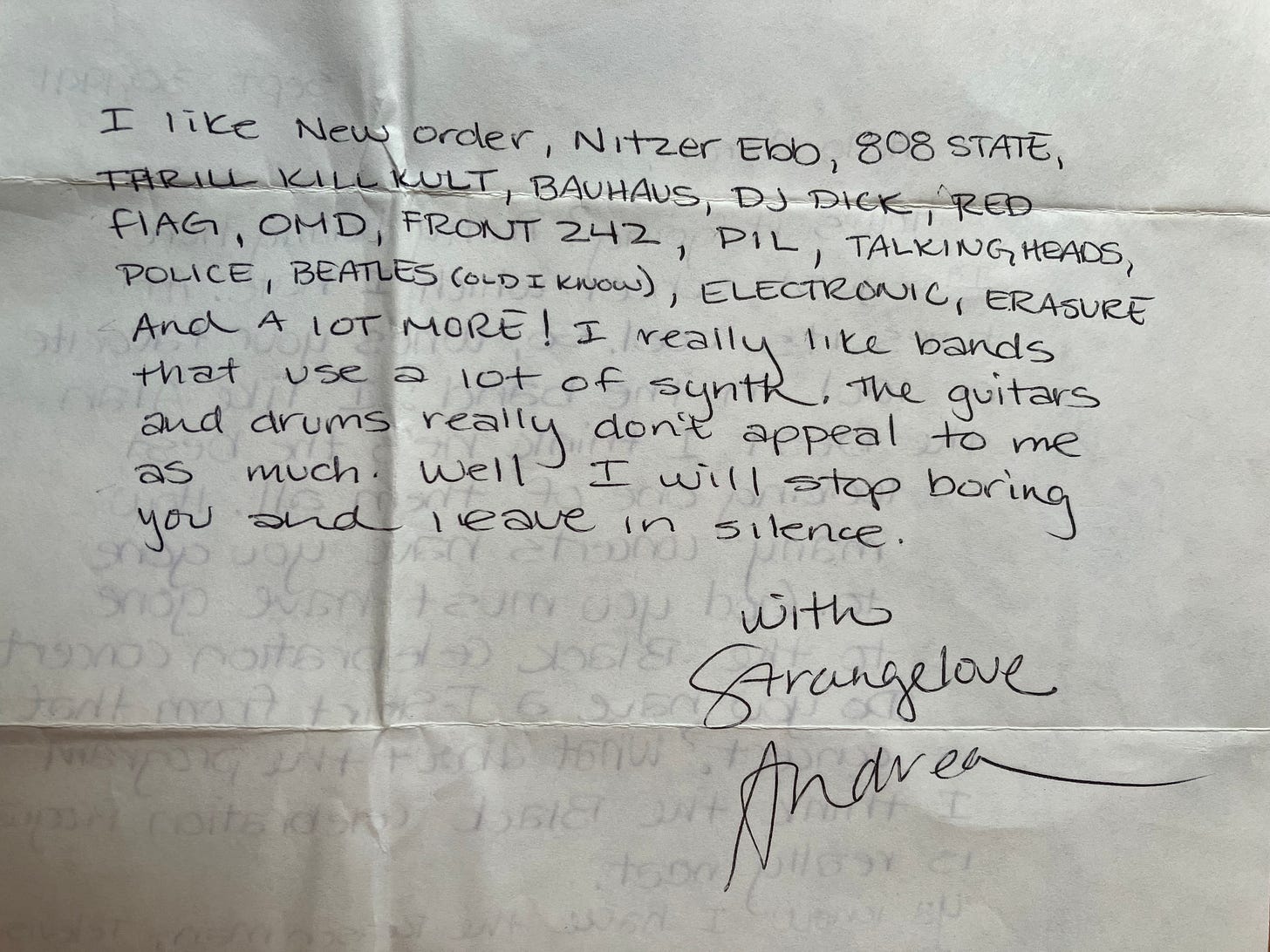

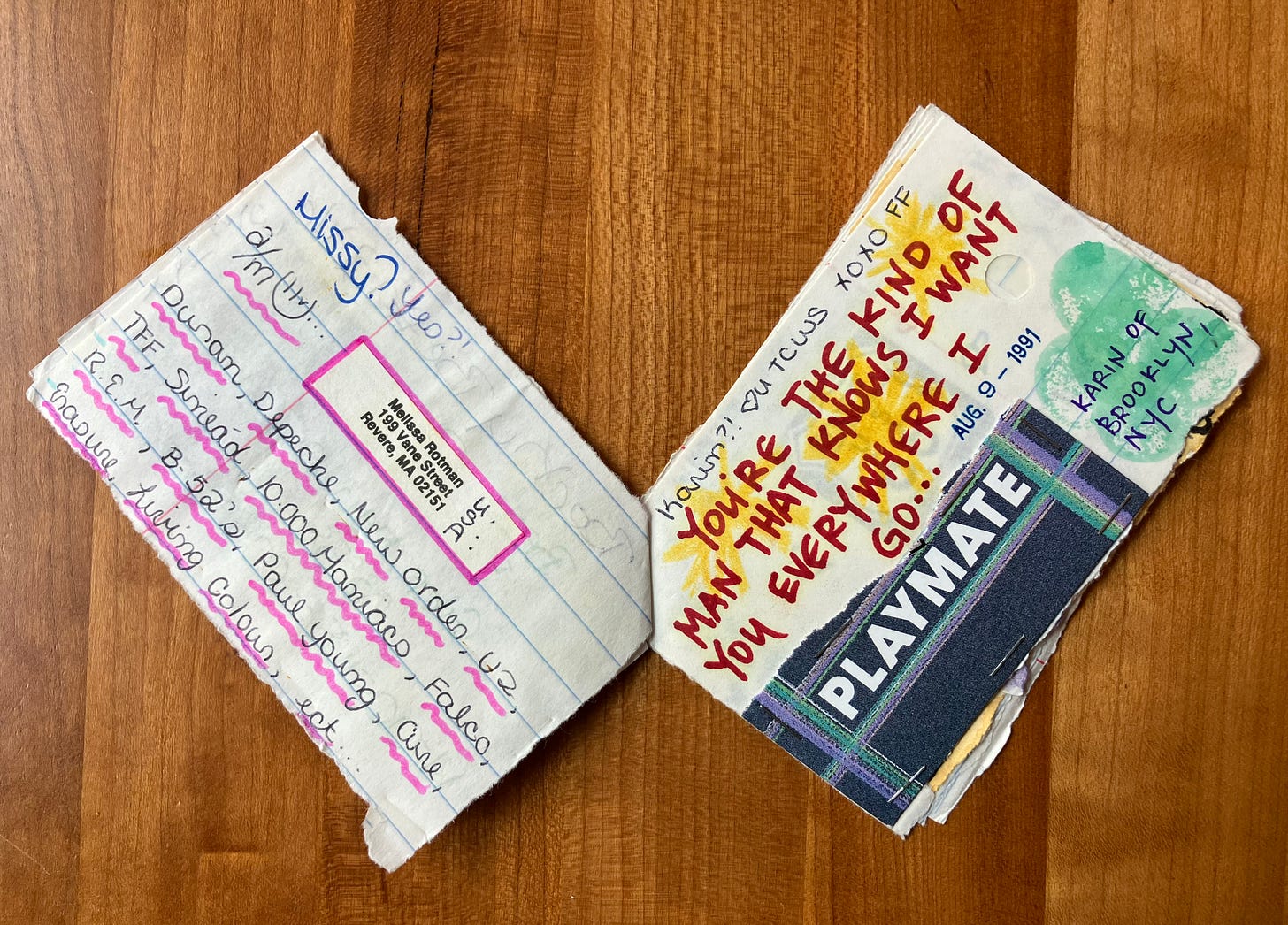

Most of these pen pals were just young fans like me who wanted more of the music they loved. Some were selling their recordings. Others were hardcore completists who wanted a copy of every show their favorite bands had ever played, in the highest possible quality, from REM to Siouxsie and the Banshees.

It was my first brush with hardcore fans and bootlegs, and I fell right in with them, even after my musical tastes broadened by 1992.

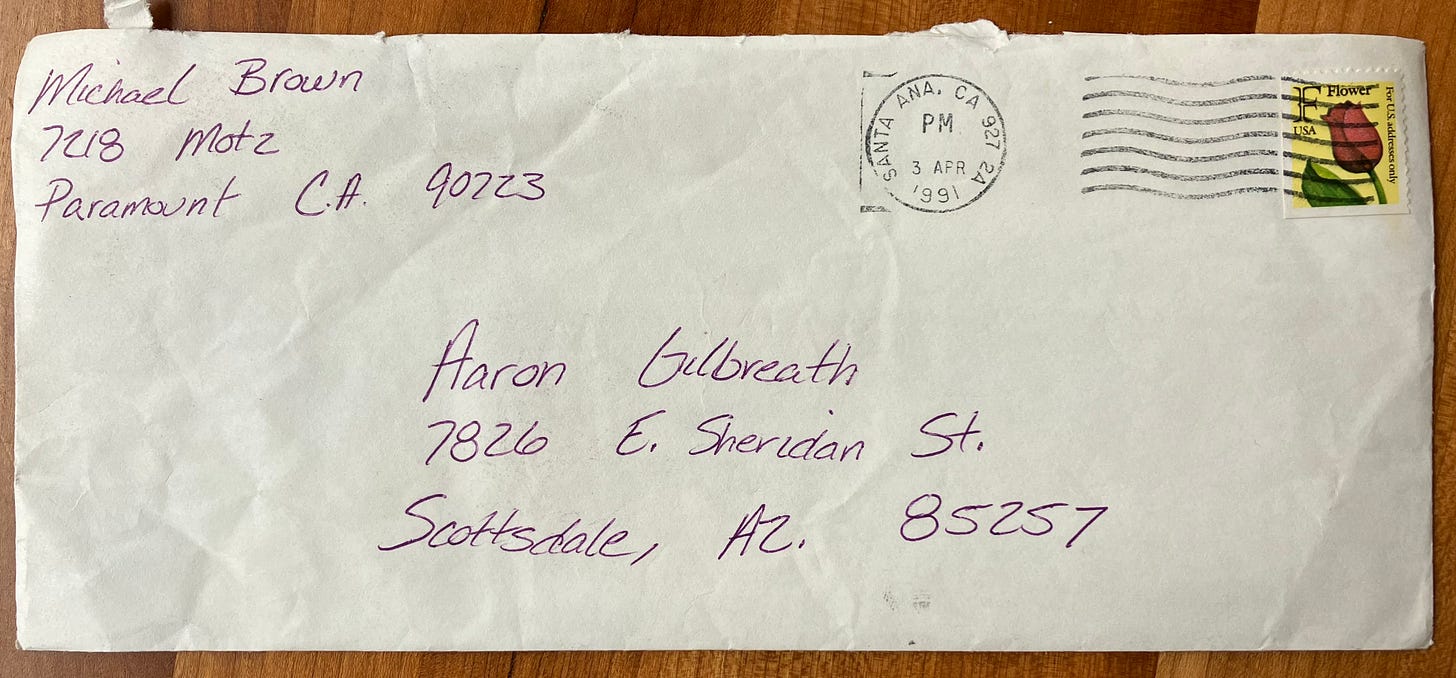

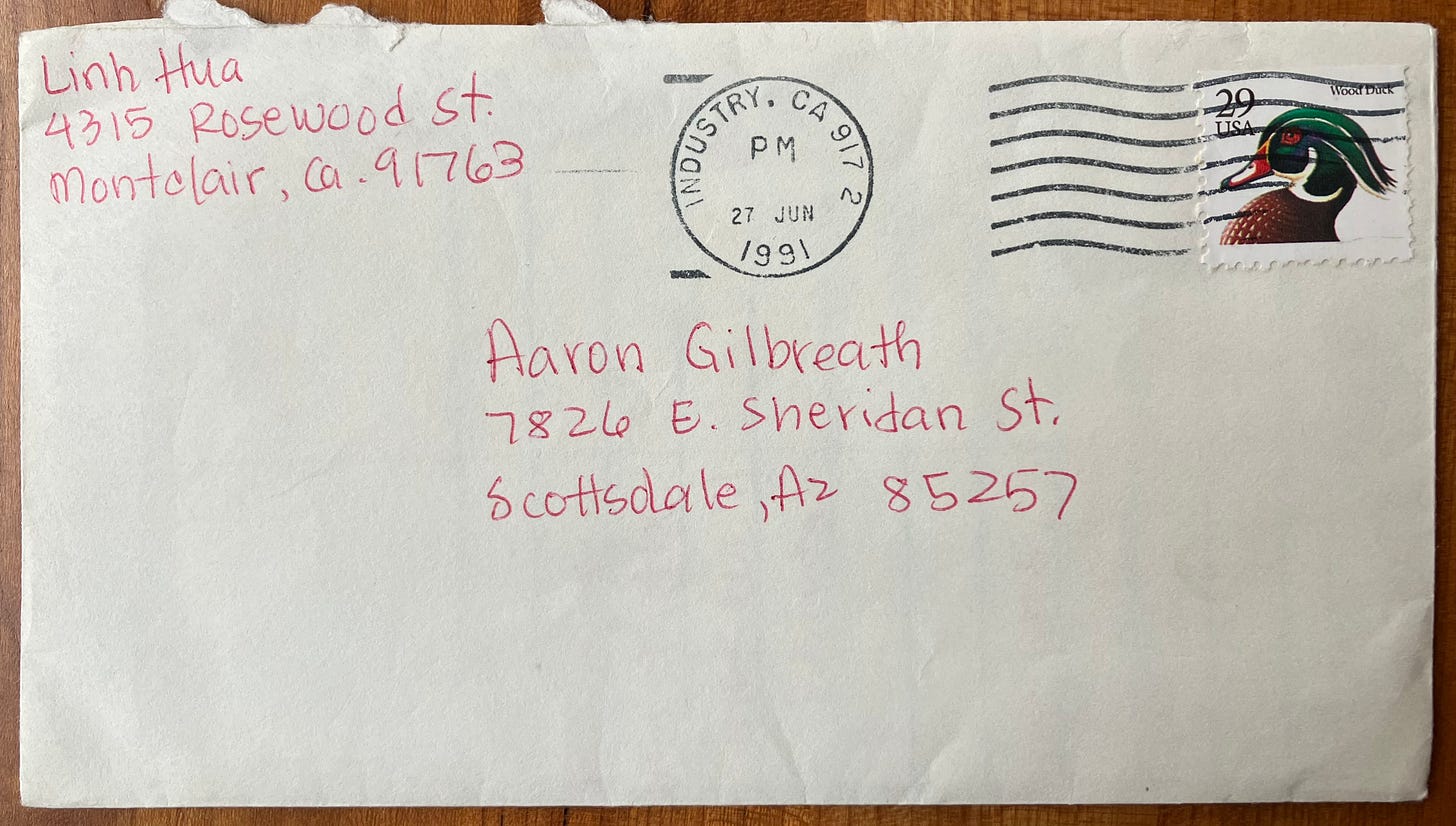

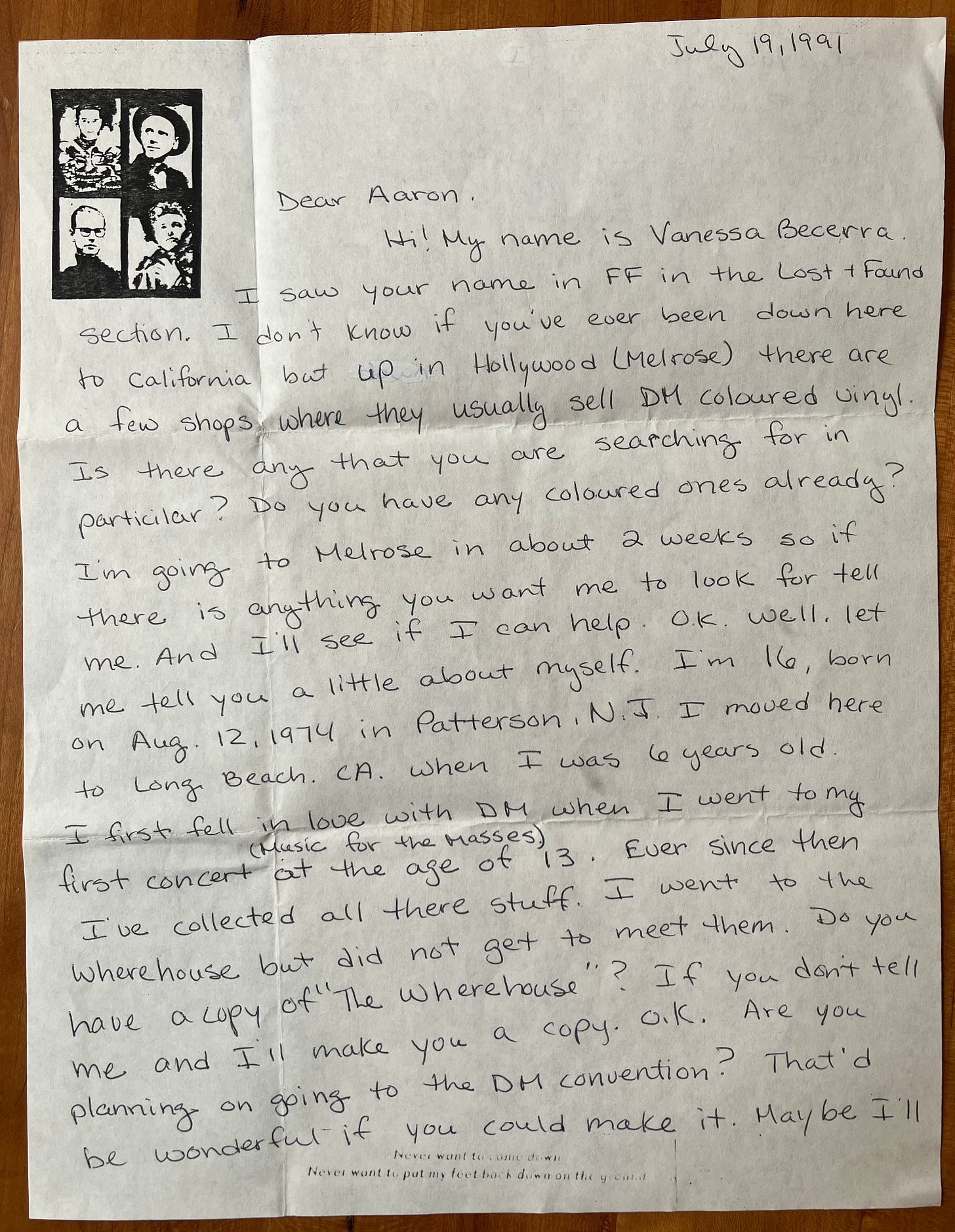

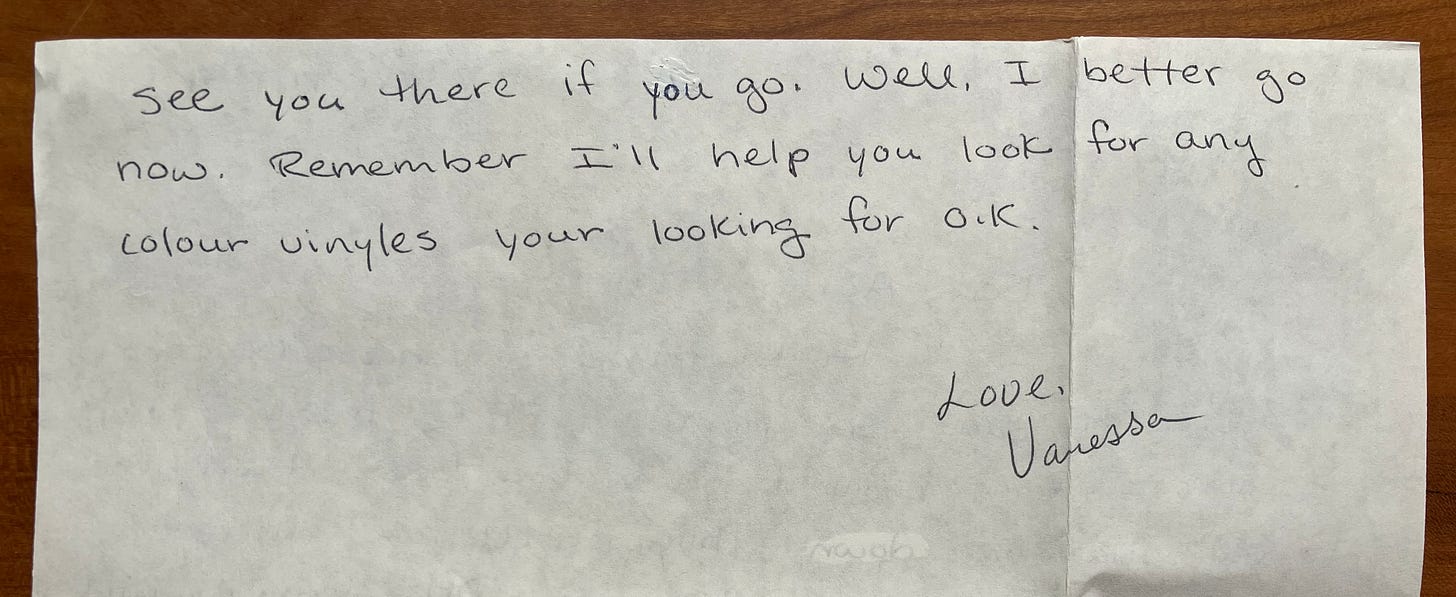

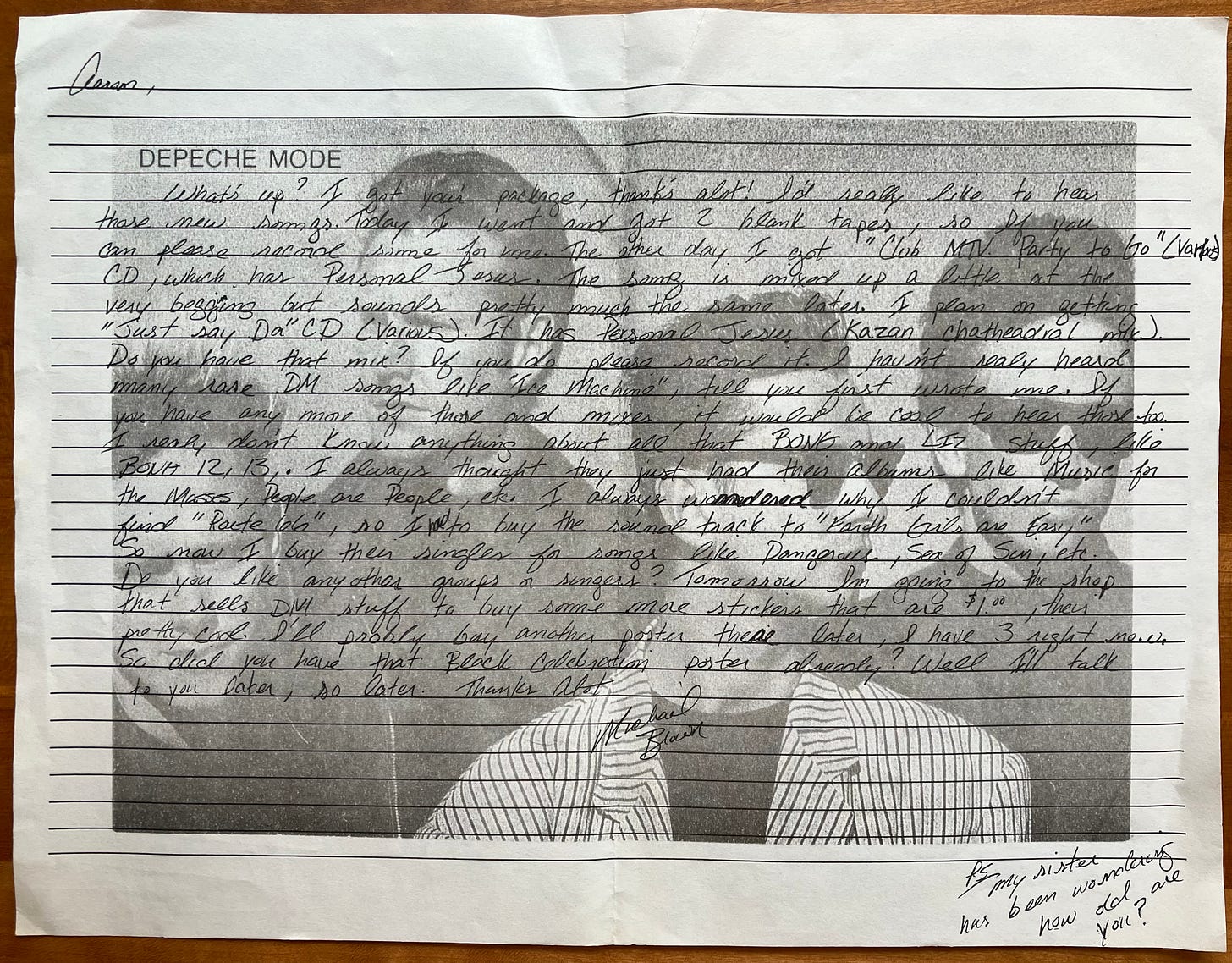

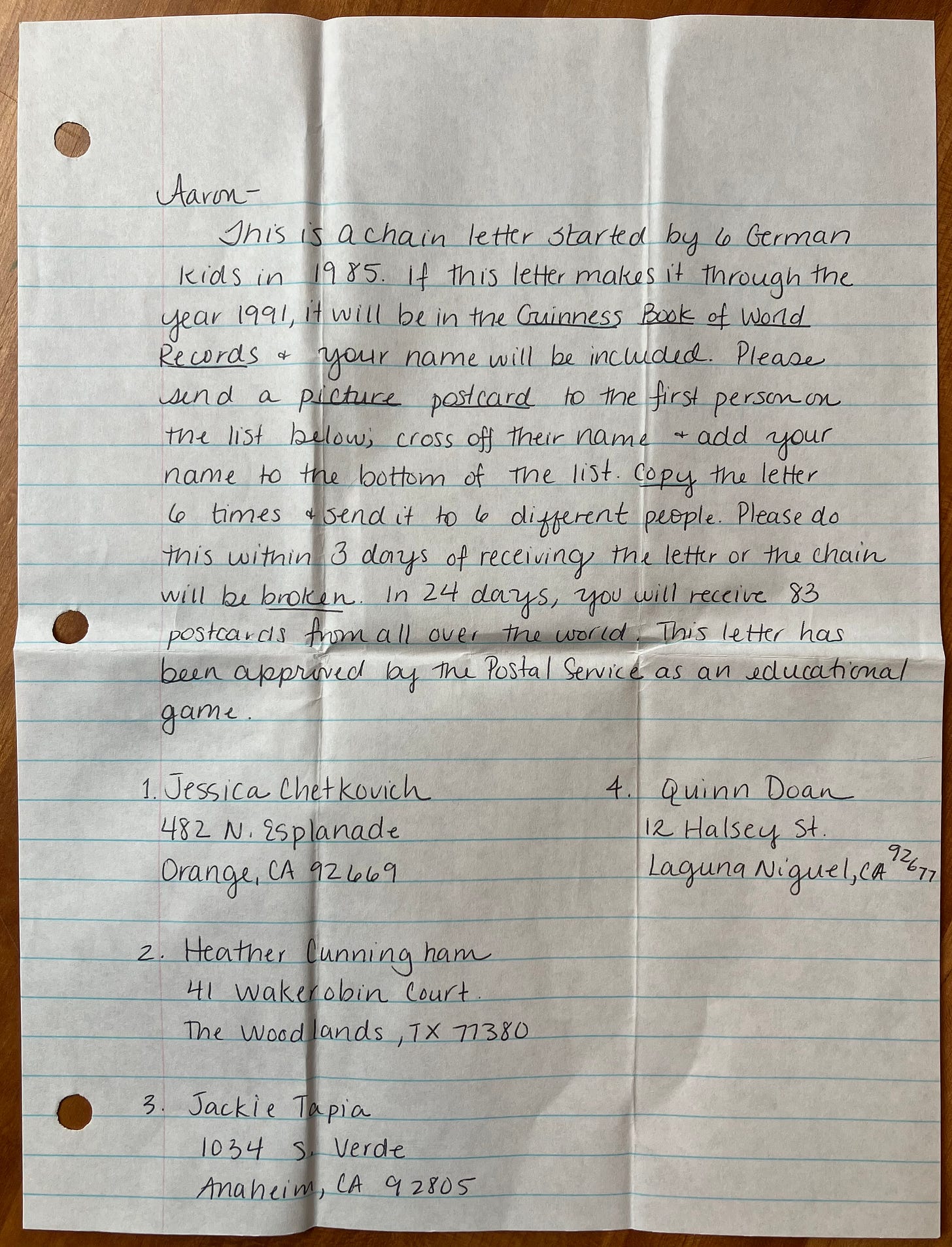

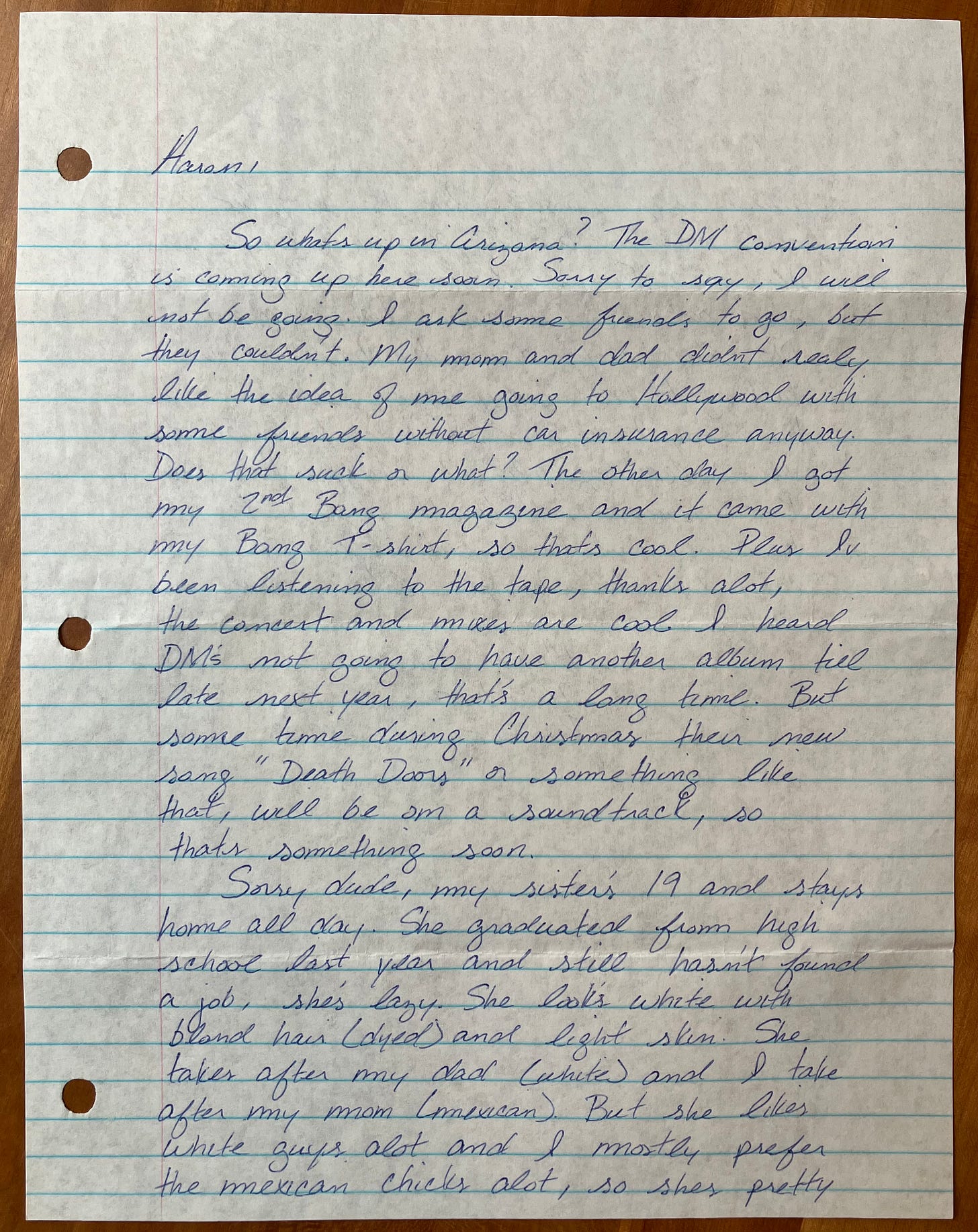

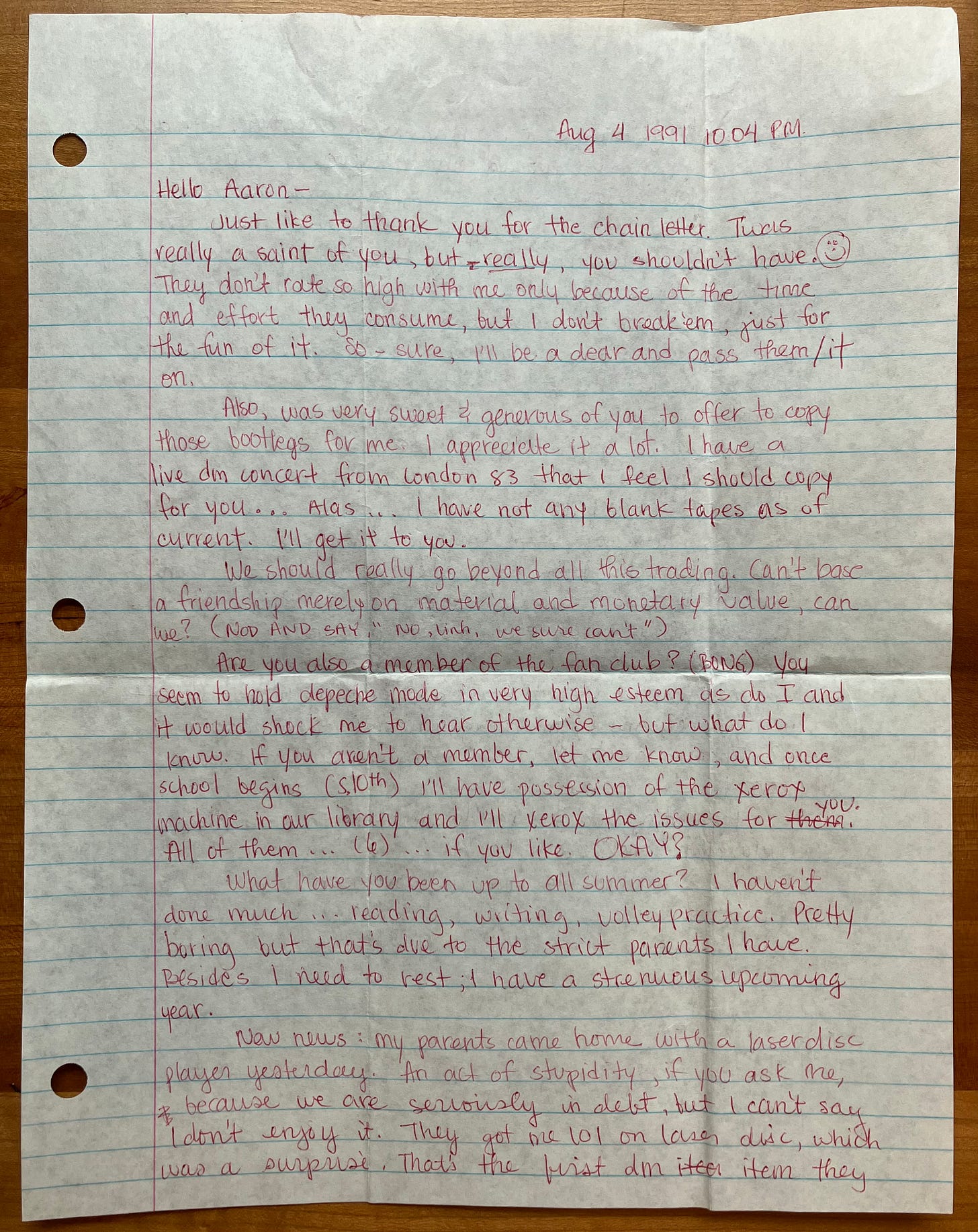

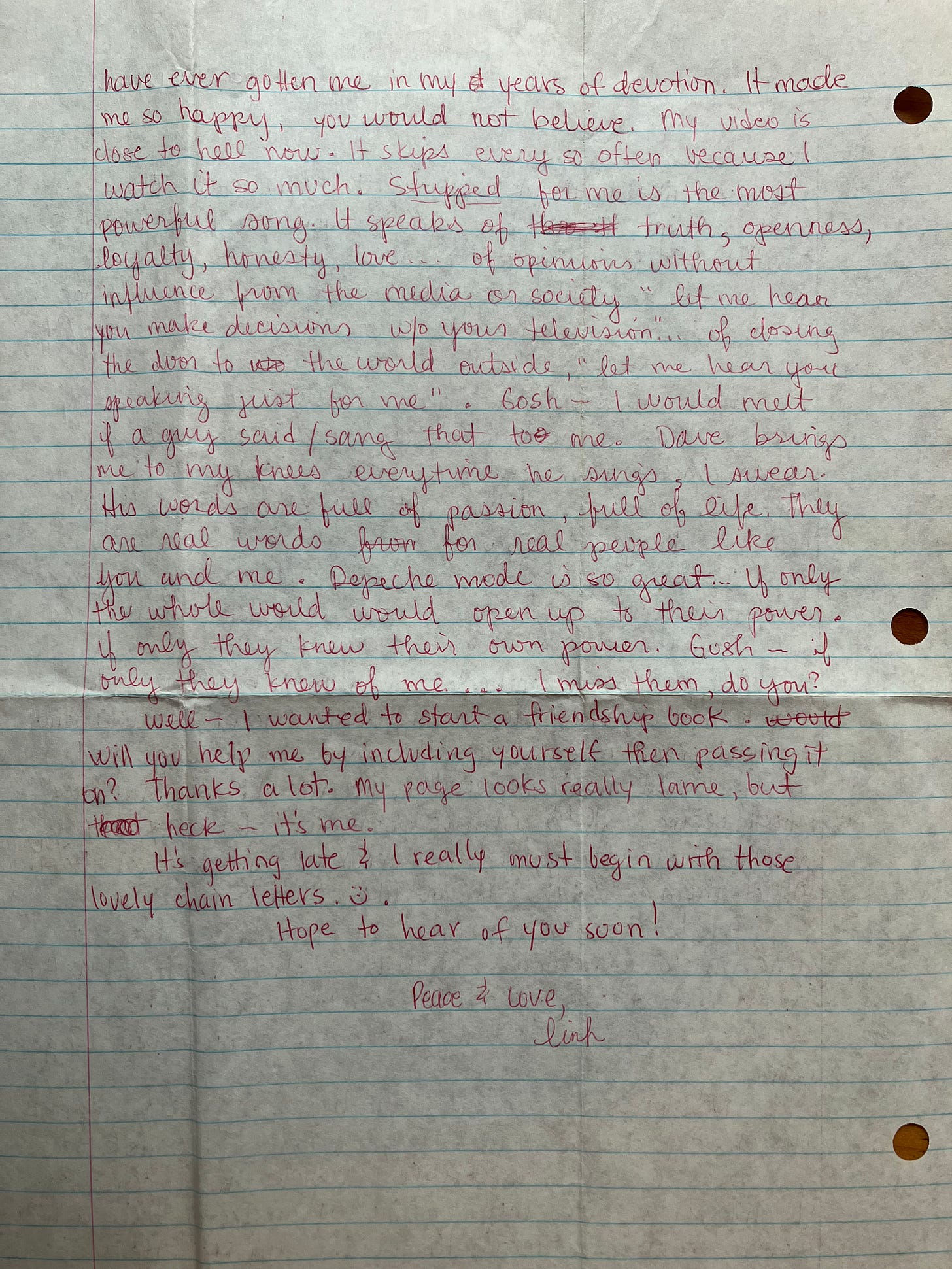

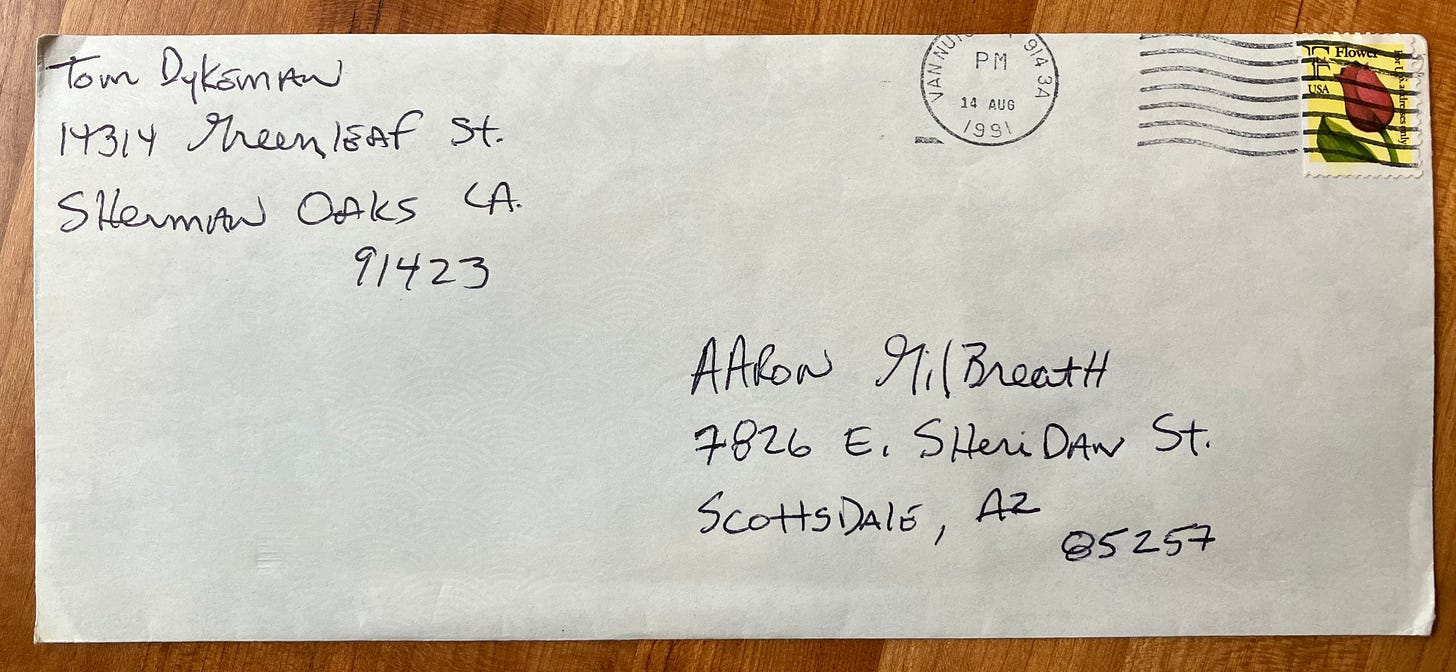

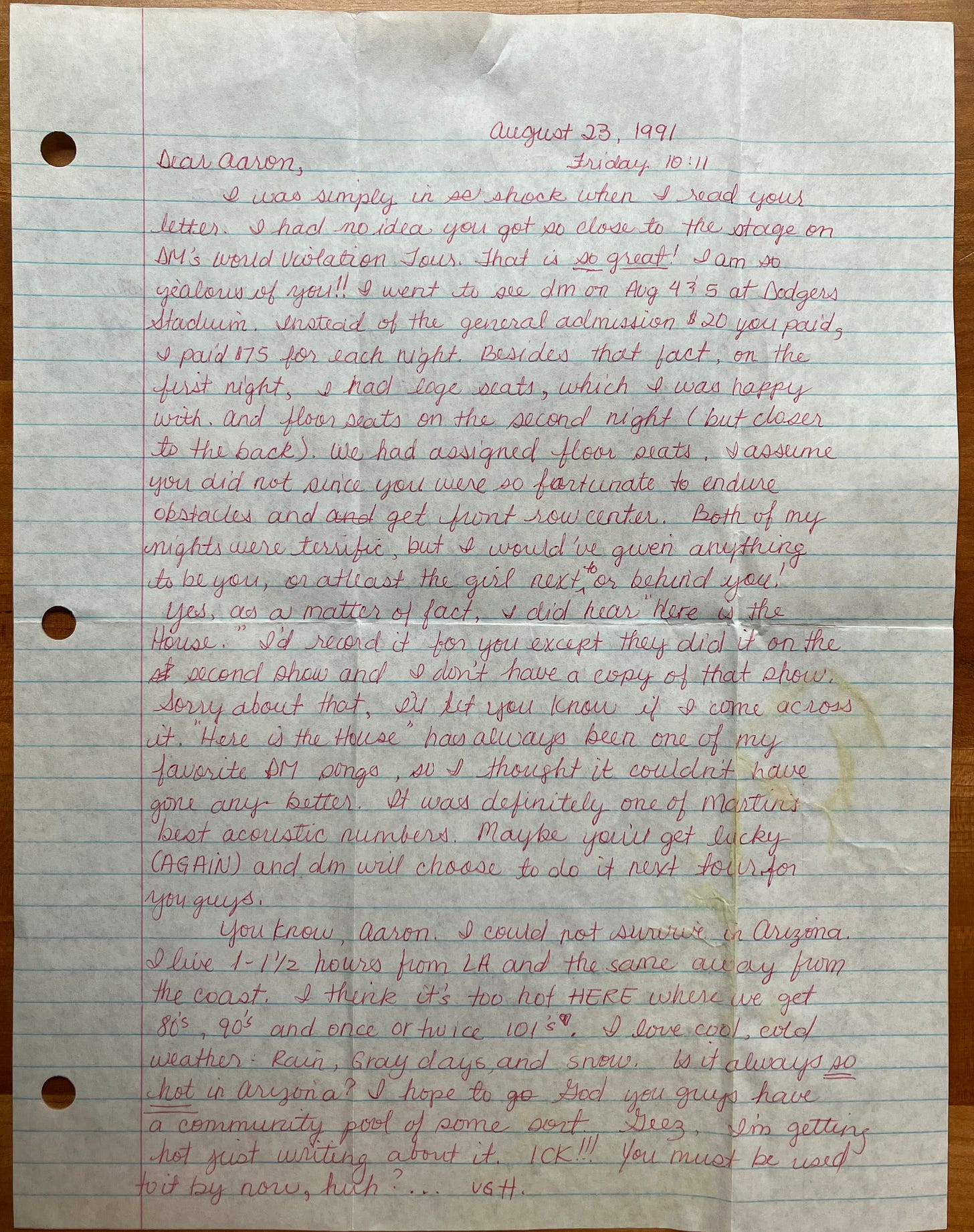

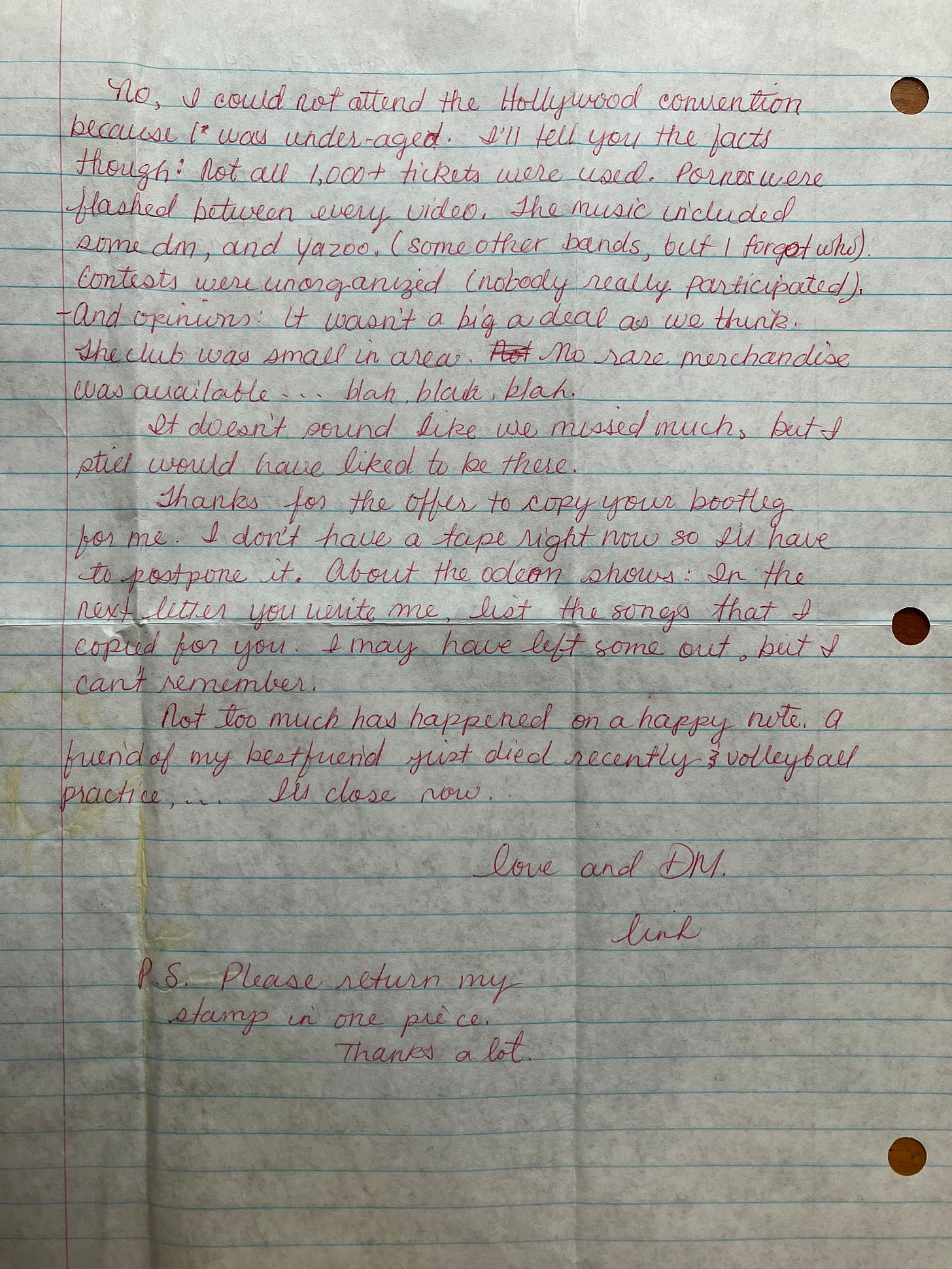

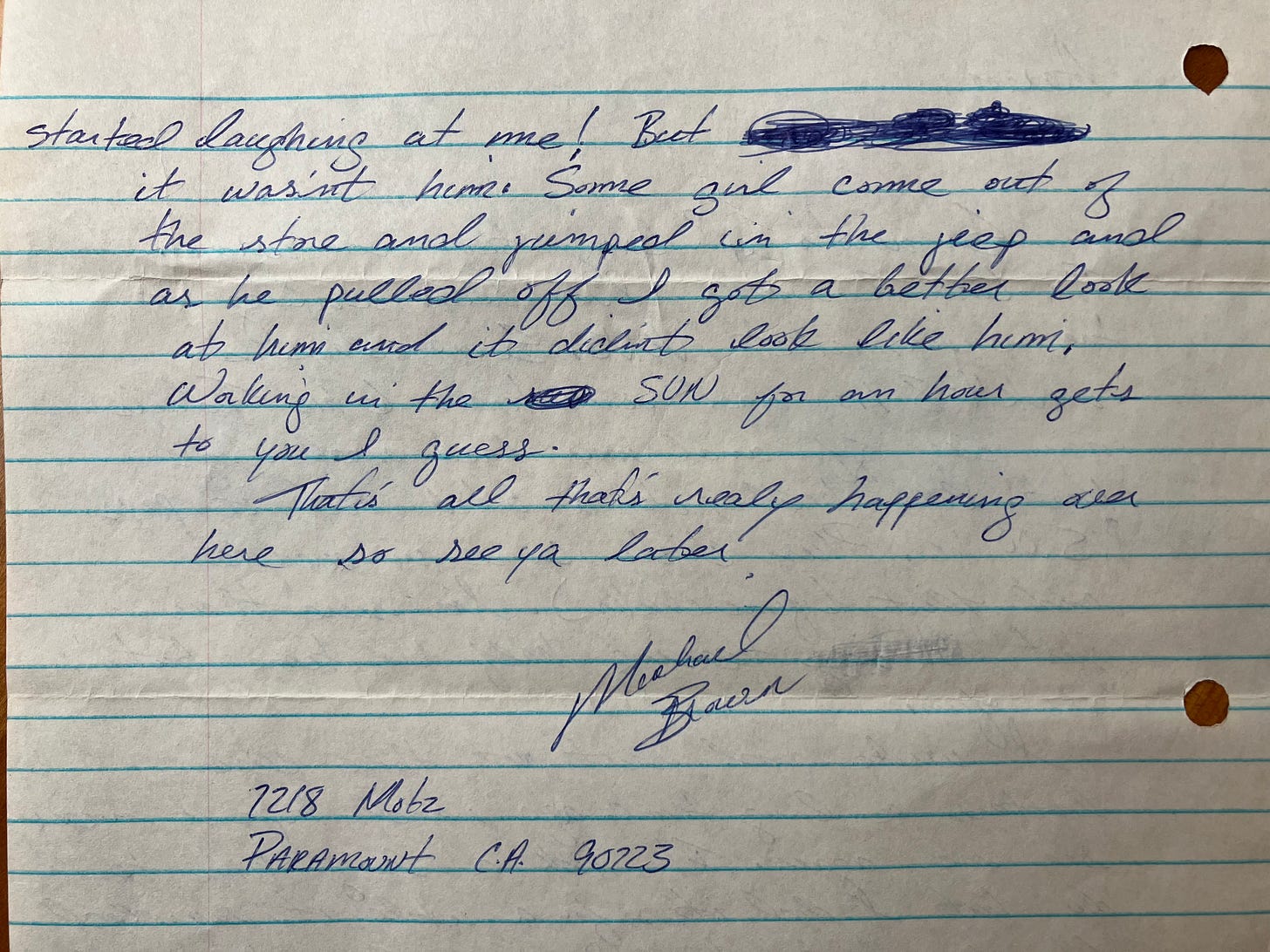

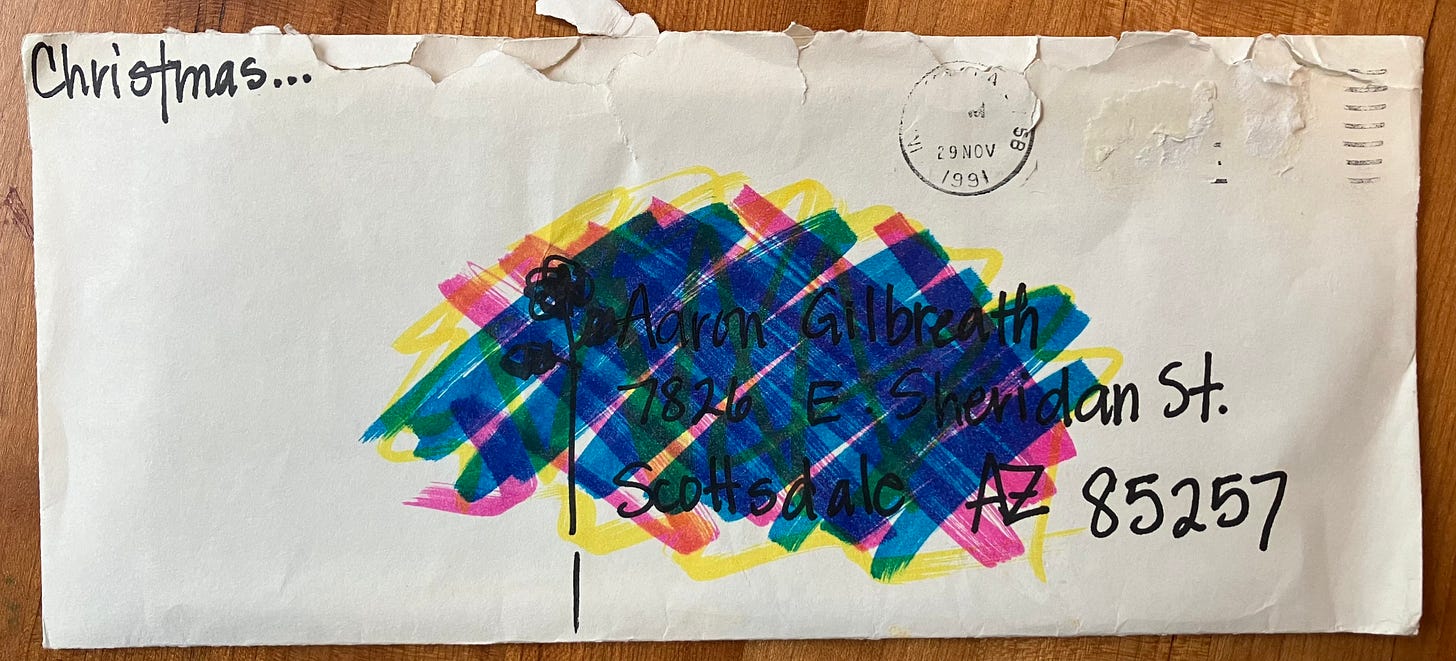

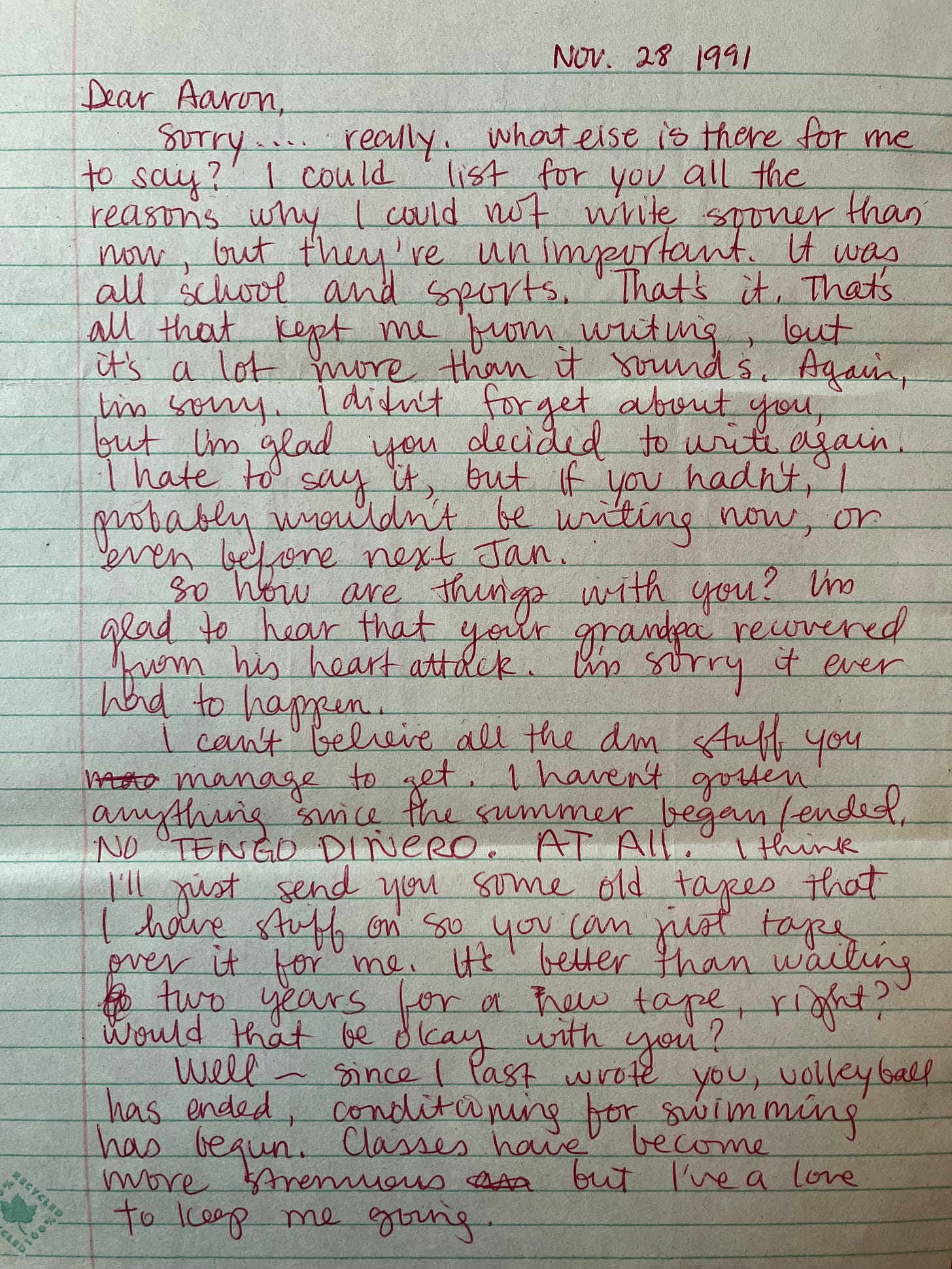

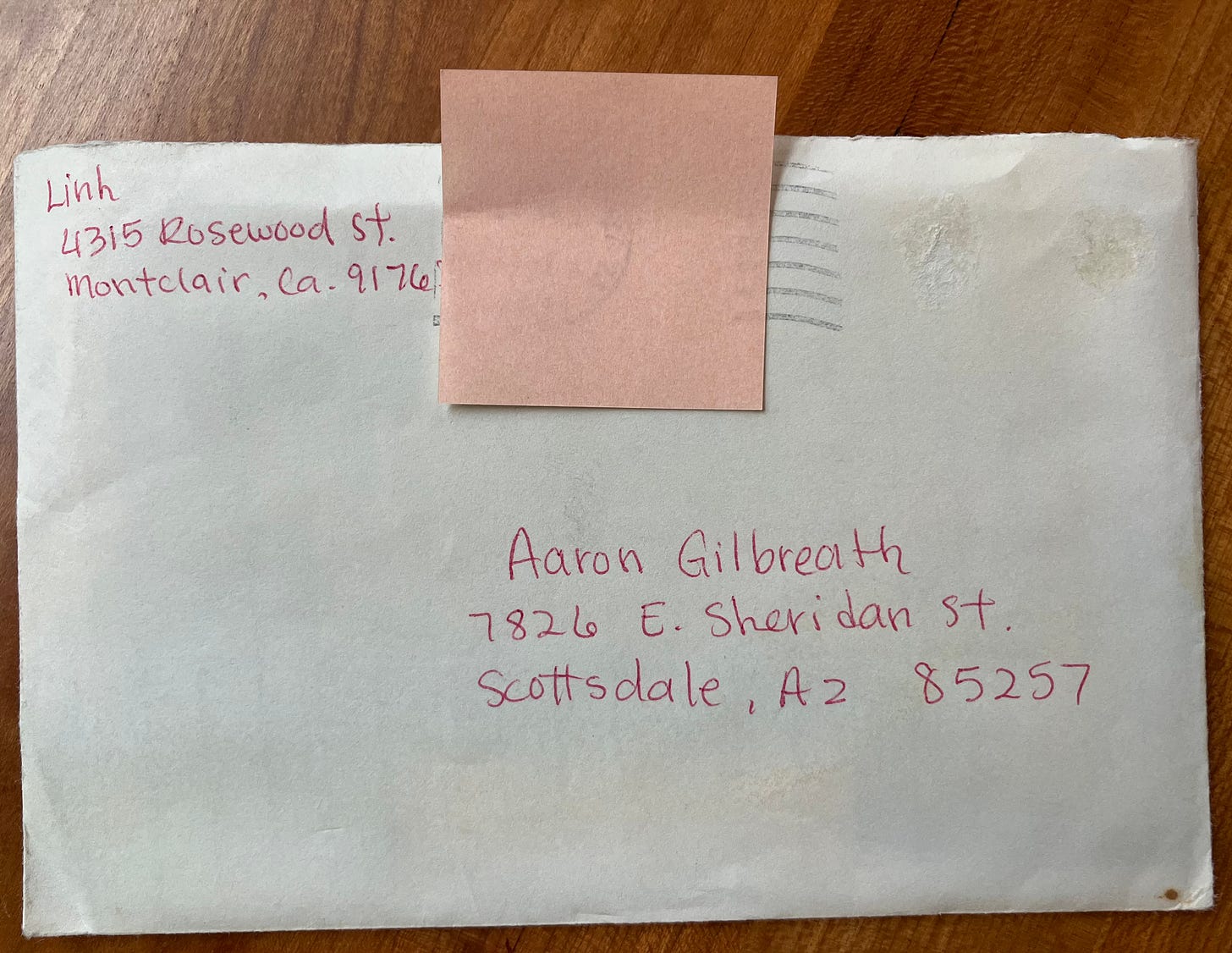

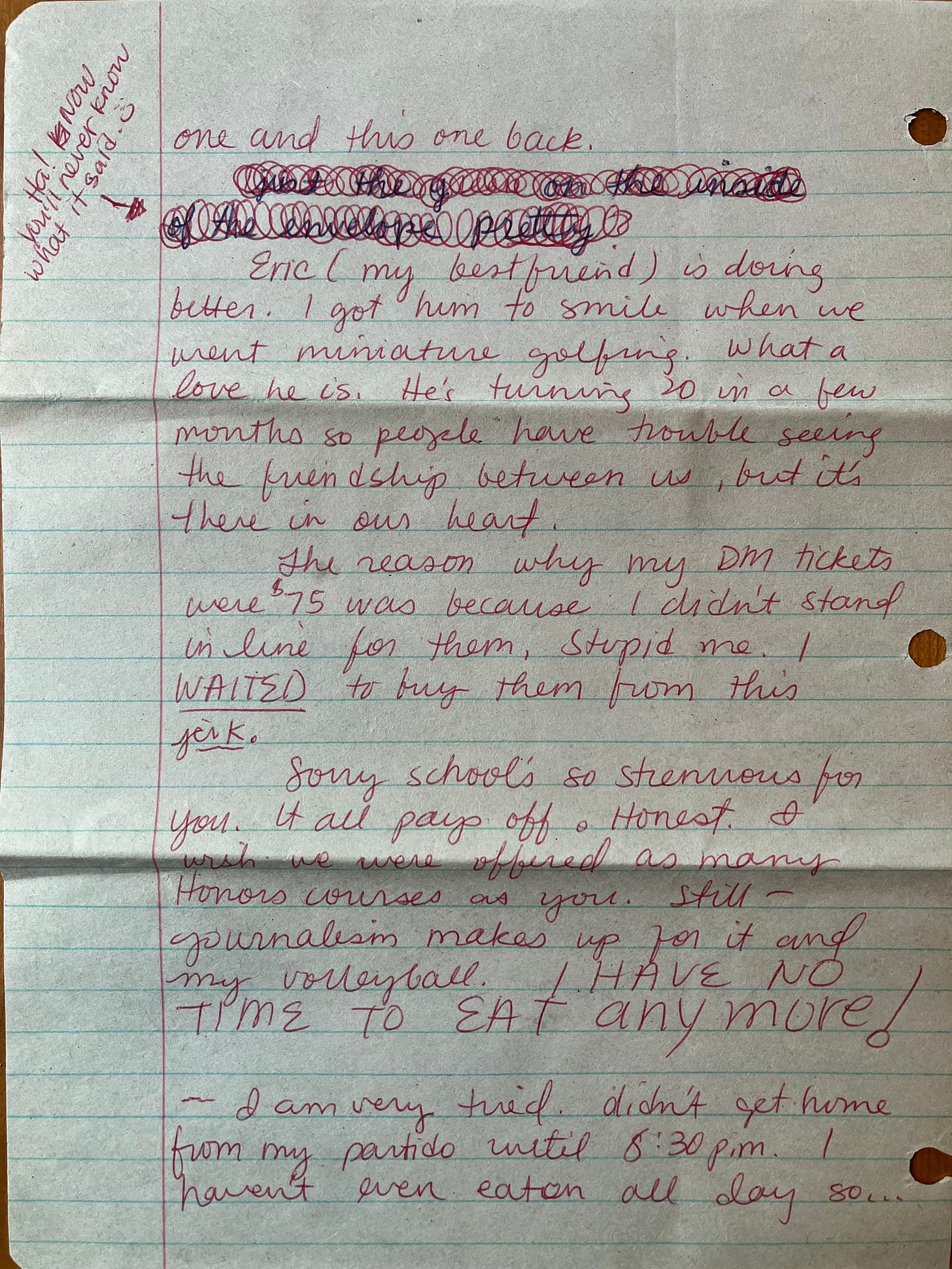

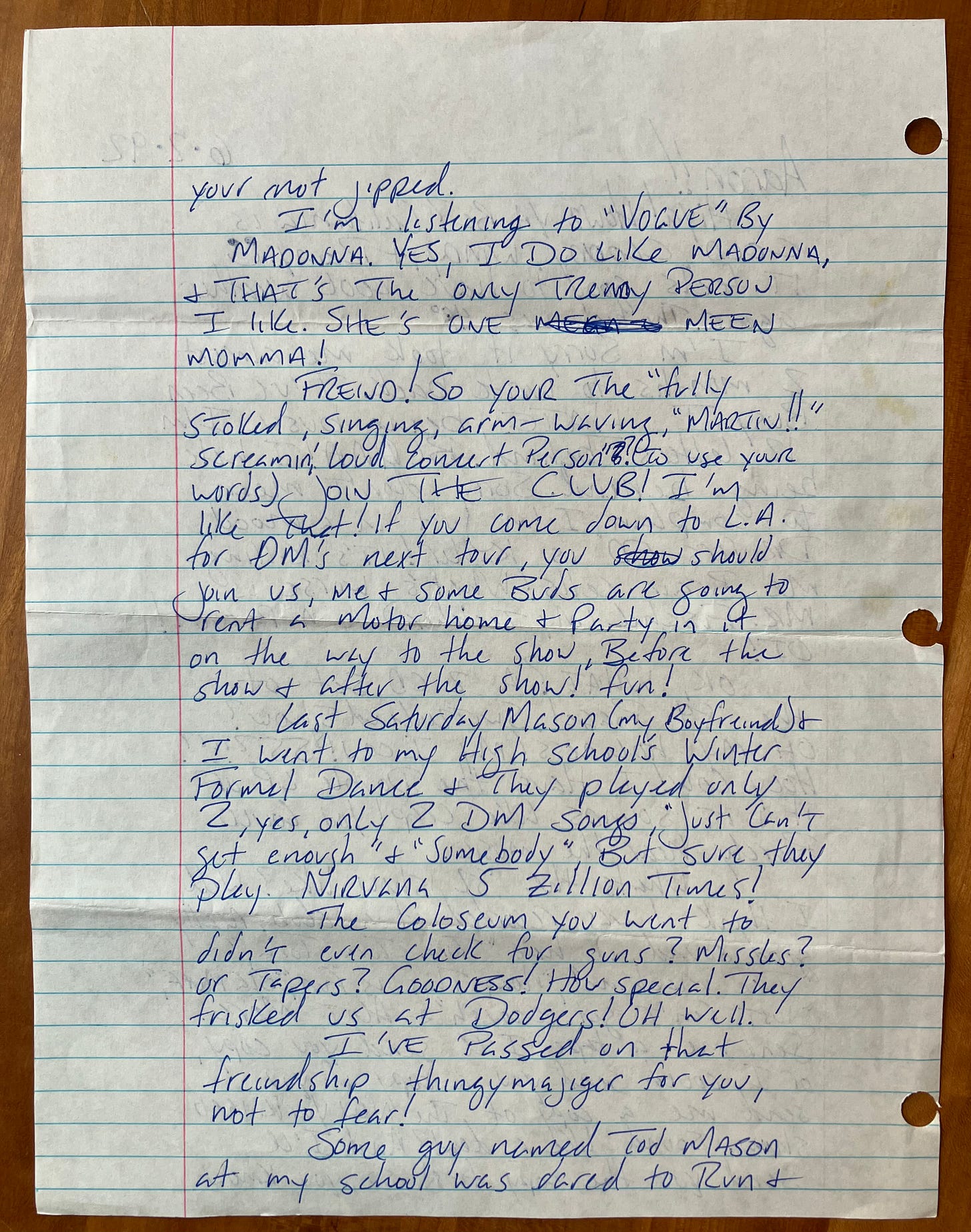

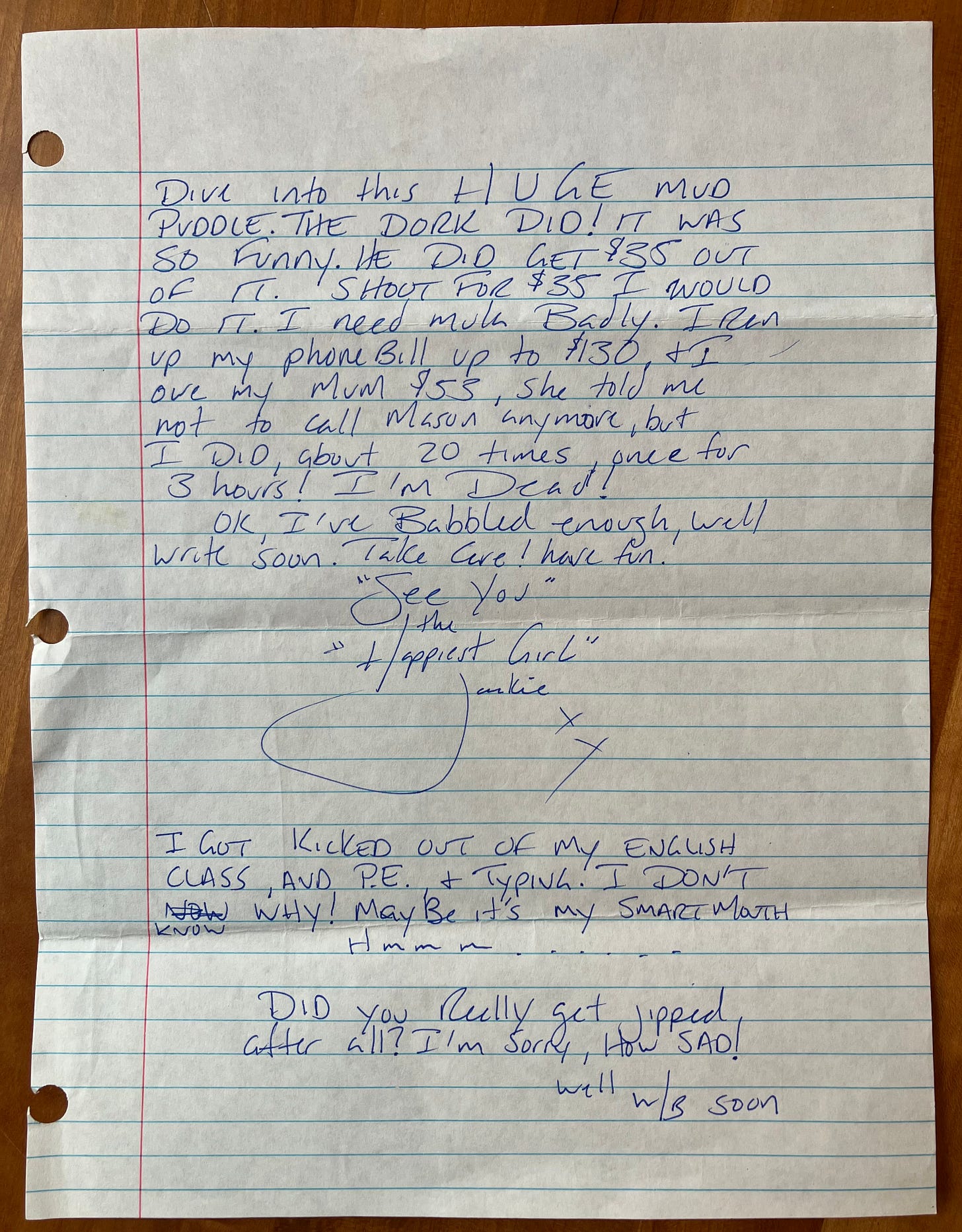

Here are all the letters I received from Depeche Mode fans, in chronological order. My letter writing started around Spring 1991 and fizzled by Spring 1992. The last letters I received went unanswered. I’d already moved on from DM to the so-called “alternative” music that got marketed to the world.

This is a time capsule of a niche underground teen network from a brief moment in time.

What’s clear among the teens is that one of the worst things you could be is boring. School was boring. Life was boring. Their town was boring. Depeche Mode and the escape of fandom was our antidote. And heaven forbid we, as letter writers, ever bored the recipients with what we wrote!

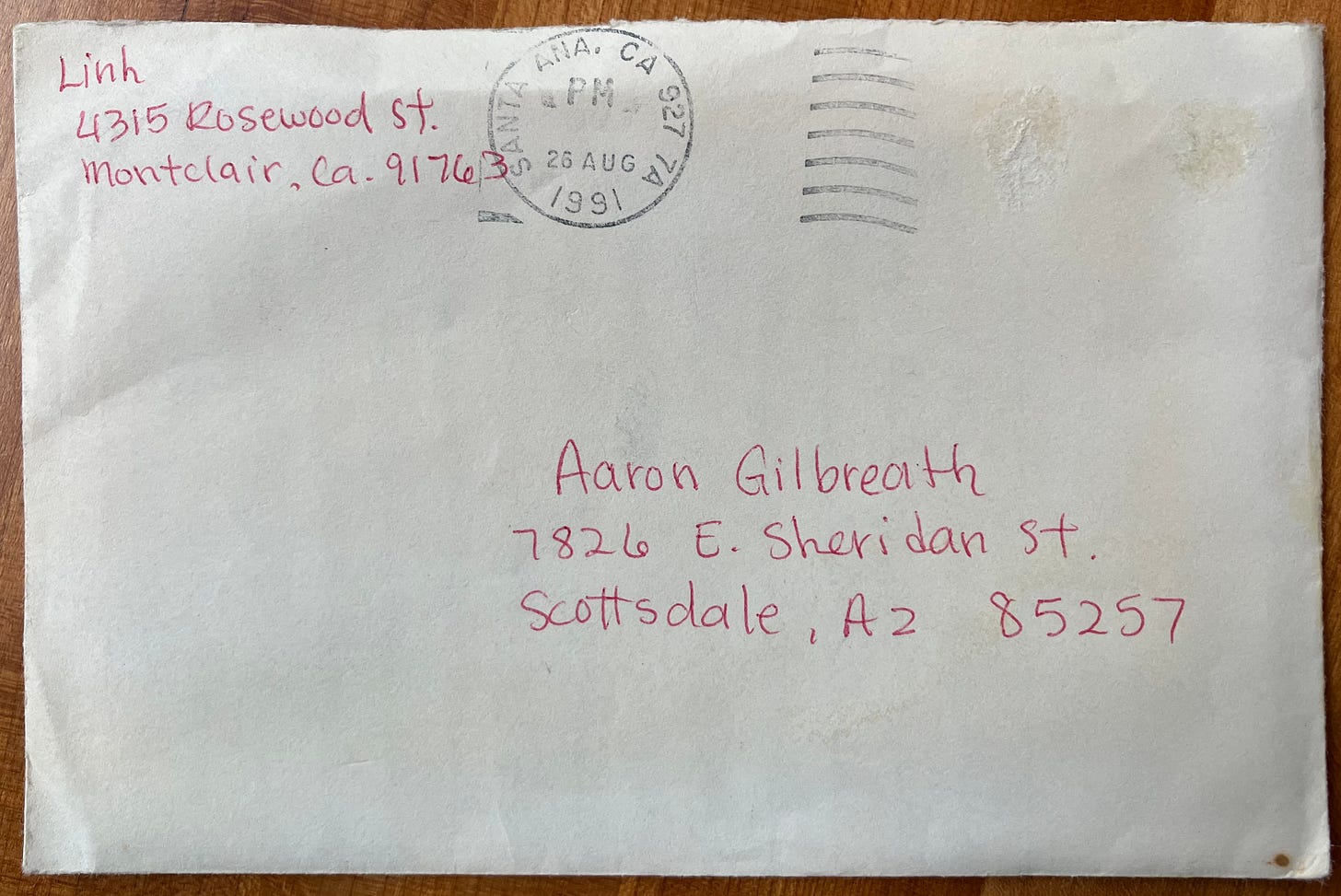

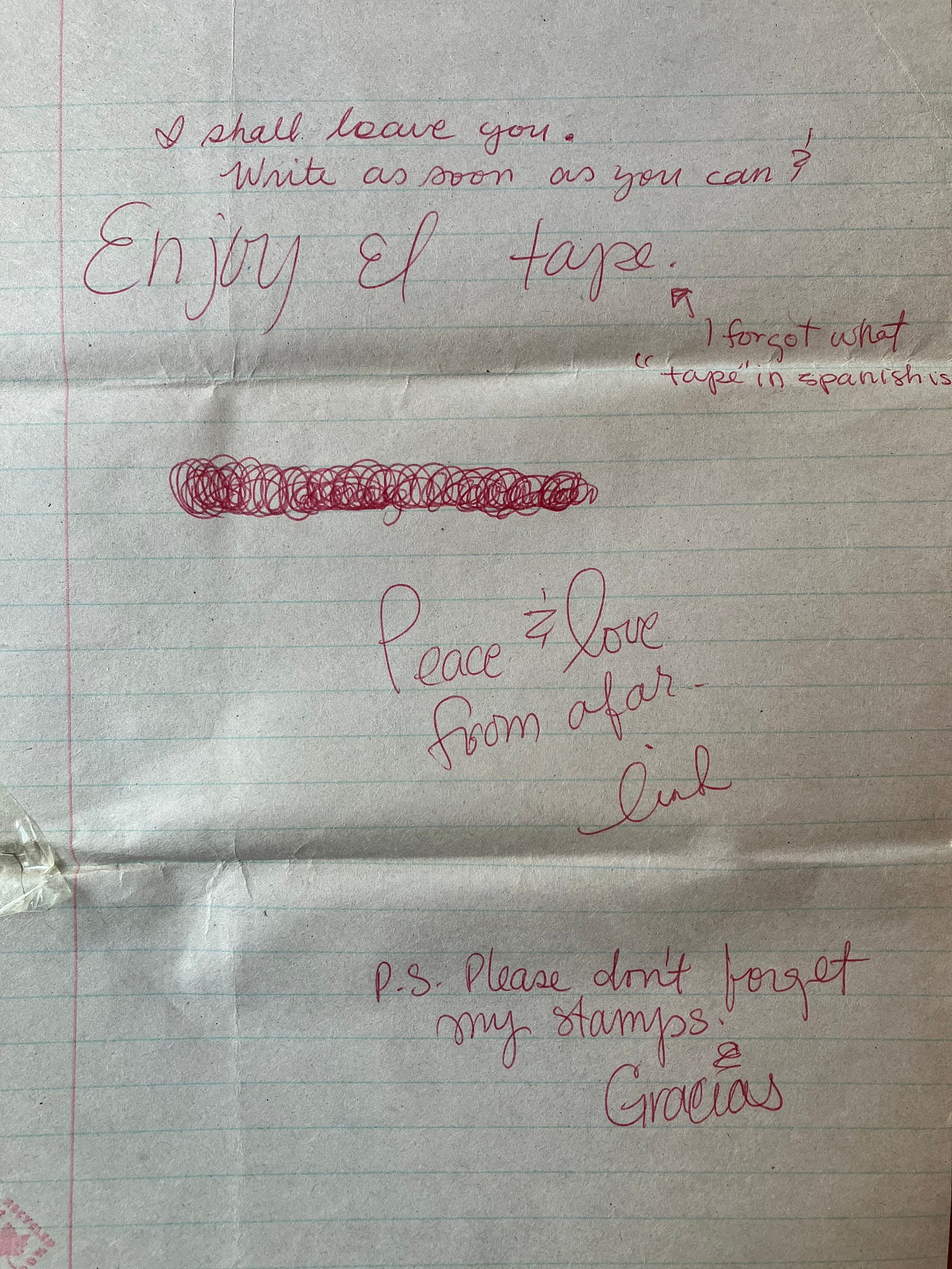

What’s extra sweet is how we teens shared our feelings and lives with strangers. As we traded letters about this band we loved, we sometimes started sharing details of our lives. I wrote to my pen pal Linh in Montclair, California about my grandpa going to the hospital and my first serious girlfriend cheating on me. We bonded. She was so sweet. And in that universal teen way, the course of just a few letters could build a powerful sense of connection—friendship, even love. Teenagers are intense. I love them for it.

Enjoy:

And that’s how it ends: abruptly, on a passionate note.

What happened to these lovely people? What became of their DM fandom and their lives? Maybe I’ll do some internet sleuthing to find out. For now, I’m grateful for their friendship.

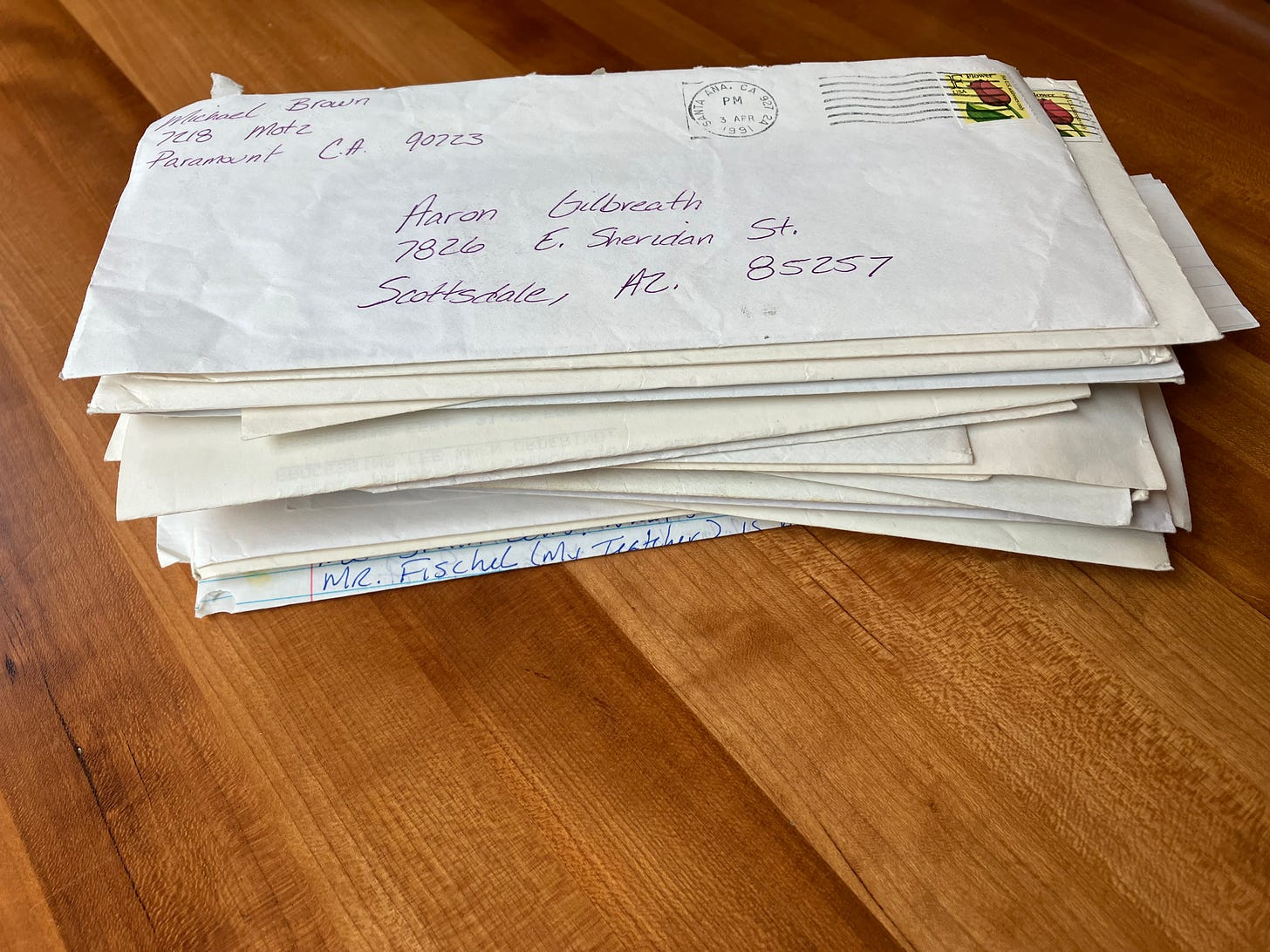

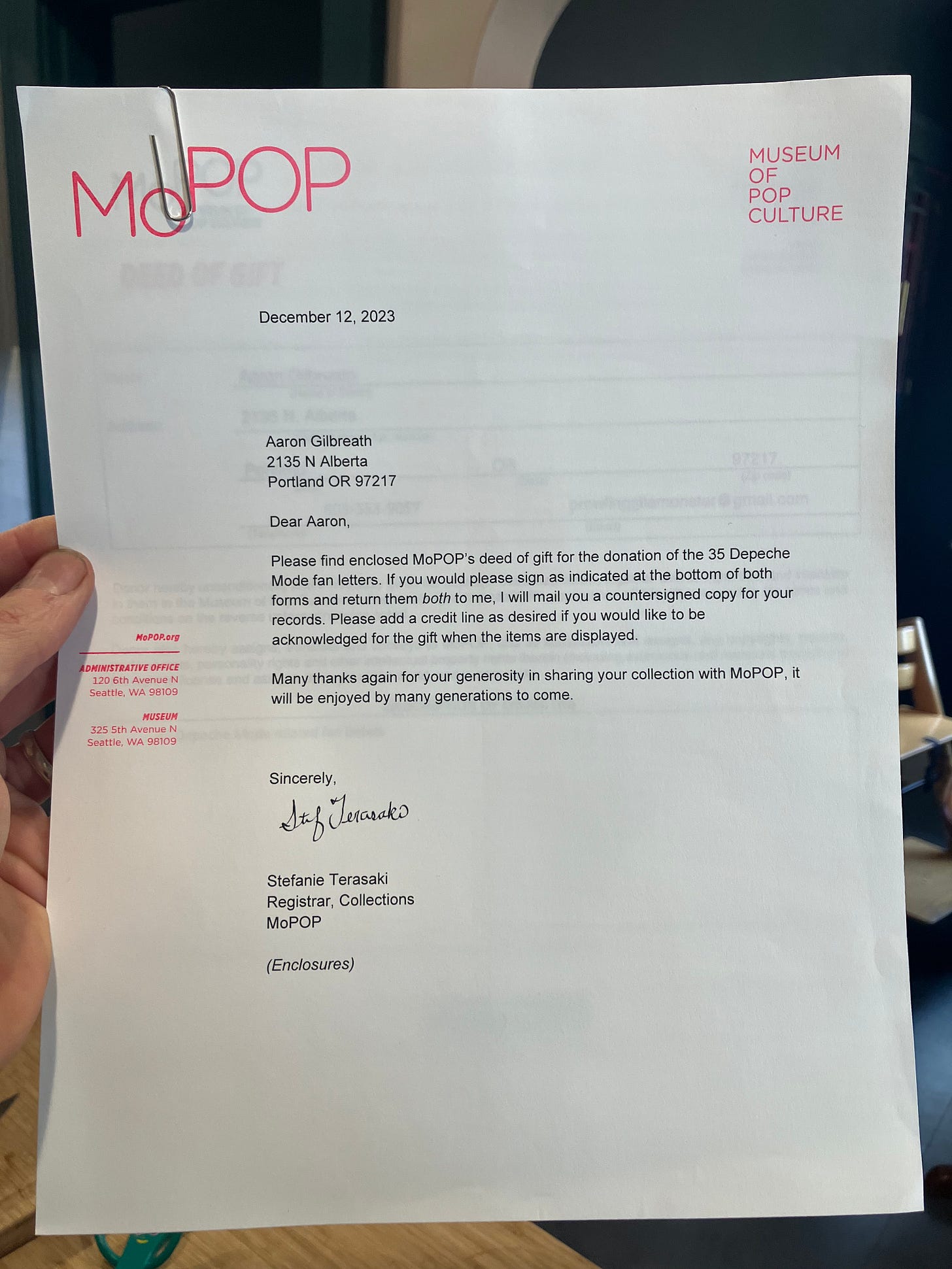

As I bundled these letters to toss them in the recycle bin, my documentary impulse stopped me, and I wondered if these had a larger cultural value.

So I emailed the Director, Curatorial, Collections and Exhibits at the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle, offering them up. The Museum had a material archive as large as their appreciation for the varied manifestations of pop culture. Fan letters embodied a niche, teen, underground network whose subculture could make its own kind of exhibit if they could gather other letters or material artifacts from it. If not an exhibit, then maybe these artifacts would be worth adding to their collection?

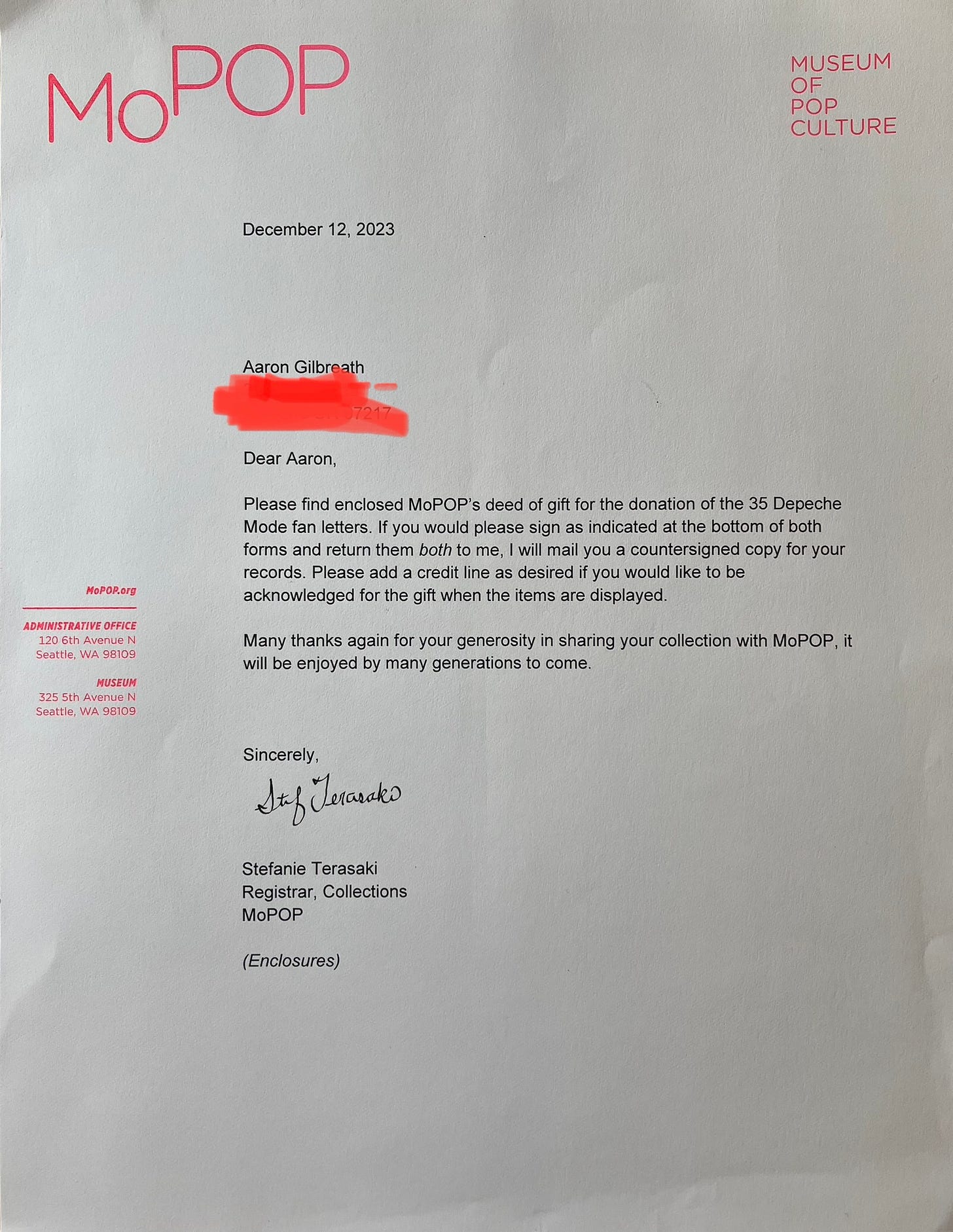

The Director emailed back: He and his team were interested. After I mailed them, the Museum’s Registrar mailed me a deed of gift to sign for my donation.

It was official: I was old enough for my childhood to be a museum artifact. Seeing kids in Nirvana t-shirts still trips me out, but this was a new level. I still made me proud.

My collection, said the letter, “will be enjoyed by many generations to come.”

This was a great one, Aaron! Aaah, the search for those elusive bootlegs and b-sides...

As someone who relies on collective memory to fill in the holes of youth (maybe we all do that?) I thoroughly enjoy your writing and perspective so much. But this one really gets me—the letters, the tapes, the true teenage connection. Sometimes I chide myself for how nostalgic I am, but this is a kind of affirmation. Why not romanticize these romantic times we had. Black Celebration forever. xo