Mother Love Bone and My Rock 'n' Roll Awakening

As underground music crossed into the mainstream in the early '90s, some of us were listening, thanks to cool friends and older siblings. But we missed a lot, too.

On April 20, 1989, a month after the release of their debut EP Shine, Mother Love Bone played a small bar named Tommy’s in Dallas, Texas.

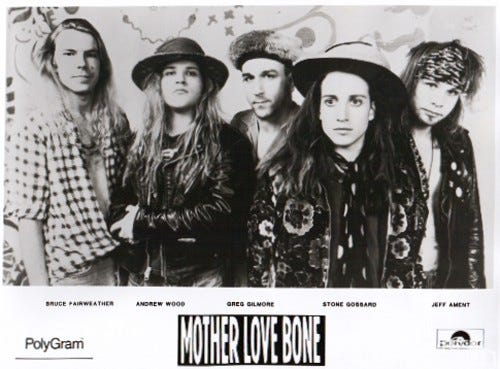

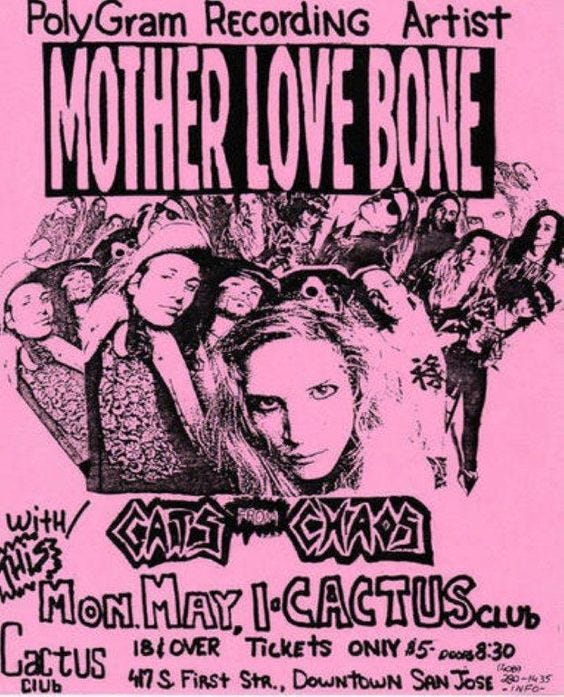

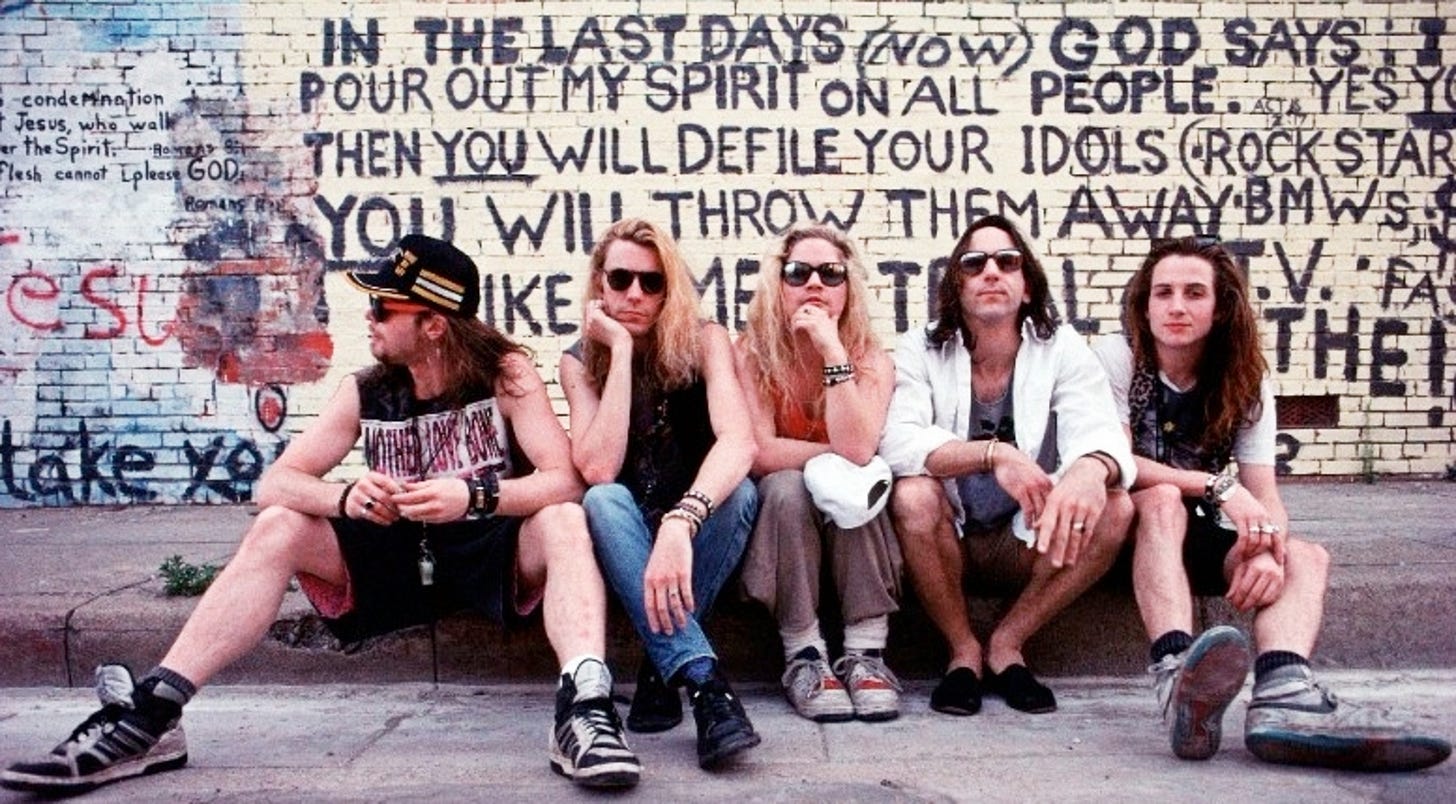

The young Seattle band had just gotten signed to a major label after a bidding war. Three of its members had defected from the influential rock band Green River because their style became more hairspray than the other guys hardcore. Love Bone sounded kind of hard rock, kind of glam. They pulled from the hair band playbook, just with better songwriting and cosmic glitter sprinkled on. Back in their native Seattle, before Green River’s singer Mark Arm innocently uttered the term ‘grunge,’ there was surprising overlap between metal and punk, but Love Bone was still hard to categorize. To promote their album, PolyGram Records sent them on a 32-show, 30-day tour opening for British glam band Dogs D’Amour. They started at The Channel in Boston. They played The Living Room in Providence, Rhode Island on March 31, wound into Canada, and played to 10 people in Rockford, Illinois after canceling their gig in St. Louis. “We played a lot of empty halls,” drummer Greg Gilmore said. “It cost us a lot of money.” That was the life of an up-and-coming band. They’d recently played a roller skating rink one month and then opened for Jane’s Addiction four months later. Tommy’s was the fifteenth show.

“Dallas, Texas and the world!” singer Andrew Wood yelled to the crowd after the first song. “You ready to get love bone eyes?” Wood was a gregarious front-man who spoke his own language, calling himself Landrew the Love Child from Olympus, playing music called Loverock, and he would give as much to an audience of three as he would a packed club. As his friend and roommate Chris Cornell said, “That guy was like a rock star when he was born. It didn’t matter if he would have never sold a single record and no one ever knew who he was, he was the only real rock star I think I ever met—from that era anyway.”

After Dallas, Mother Love Bone headed west to Austin, Odessa, and then to my hometown of Phoenix, where they played some biker joint called The Desperado on April 26, 1989. I was 14. Nirvana was two, Soundgarden was five, and Alice in Chains was still pretty hairspray. Few Americans remember the headliners Dogs D’Amour, but Wood’s short-lived band became legendary. They were one of the first to awaken the world to the Seattle music that would define the 1990s. In April, 1989, changes were brewing in American music culture that were about to let kids like me have our own musical awakening.

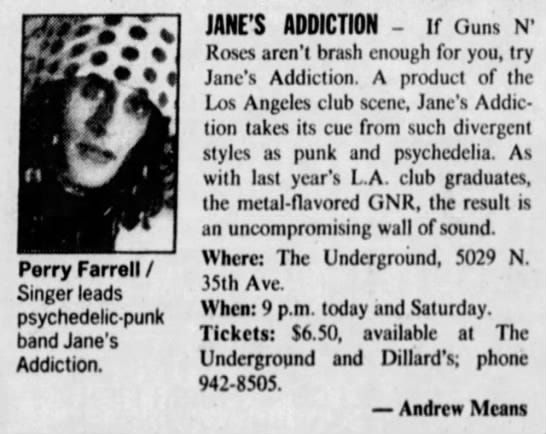

Because the Love Bone show was on a Wednesday, surely I was doing homework in my bedroom while Wood greeted the crowd with something like, “Hello central Phoenix!” My friend JR turned me onto the band in the following months, which was too late to catch their only Arizona show. That year, I also missed Jane’s Addiction’s February show at a tiny defunct club called The Underground, but my friend Chris went, because his sister was cool enough to take him there.

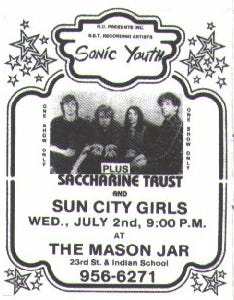

I also missed Meat Puppets playing the famous Big Surf water park near my house in September 1989. And I missed Nirvana’s June, 1989 show at the nearby Sun Club, where they played Bleach for a few people, second of four bands for a show celebrating the Sun City Girls’ Asian tour. 1989 was my year of misses, though that’s what it meant to grow up on the cusp of the ’90s. You were either old enough to go to cool shows, old enough but not in-the-know, or still too young to have heard of these bands. Of course this was true for kids all over the country. Indie bands drove crowded rental vans across the U.S. to perform, and most regions had their underground clubs, like The Blind Pig in Ann Arbor and The 40 Watt in Atlanta. My wife grew up in Olympia, Washington and was just young enough to miss all those killer shows by Hole, Bratmobile, L7—and Dave Grohl’s first show with Nirvana—at venues down the street from her house. When she finally saw Hole play, it was in Seattle. Ugh, the misery of hindsight! My friend Pete tells a story about driving by a 1983 Black Flag gig in San Diego and how the gnarly punks outside the club intimidated him too much to go in. By ’84 he’d been to enough hardcore shows not to care, but one year can make a big difference in a young listener’s life. In Phoenix, the issue was particularly acute.

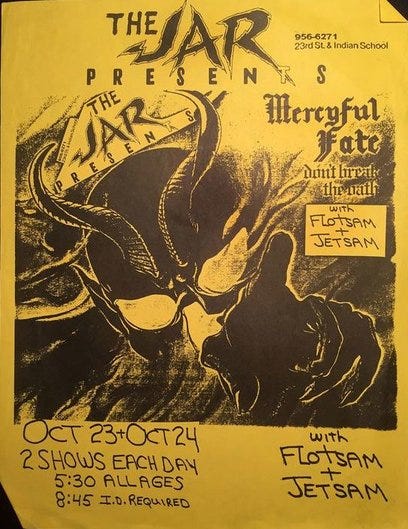

Set between important markets in Texas and California, Phoenix was a touring rock band's last stop before Los Angeles. Everyone needed to play Los Angeles. Record company talent scouts prowled famous LA venues like The Roxy and Whisky A Go-Go, and if a band created enough buzz there, they could get noticed and land a record contract. Bands played Phoenix because it was six hours from LA, it was too big to ignore, and a Phoenix gig could earn them enough free food and gas money to get them to the next gig. My city had tons of small rock and country venues. There was Long Wong’s Hot Wings on Mill Avenue, Mr. Lucky’s on Grand, and a slew of now shuttered places like Edcel’s Attic, Dooley’s, and Hollywood Alley. Three miles down the street from my high school was The Mason Jar, one of the busiest of them all. Soon-to-be legendary bands like Metallica, Fishbone, Guns N’ Roses, Sonic Youth, and Red Hot Chili Peppers all played to small crowds at The Jar in the late 1980s, a stone’s throw from my classrooms, and in 1989, I was barely aware of any of them.

A man named Franco Gagliano owned The Jar. Short with long hair and a lush tan, he wore colorful vests and kept the top buttons of his silken shirts undone to display his gold rope necklaces, and no matter how popular or obscure the visiting band, he photographed himself with them and hung the framed image on the club's wall like a trophy hunter with a stag’s head. The interior was literally covered with framed photos of a smiling Franco standing next to people like John Entwistle, Drivin’ N Cryin’, Joan Jett, ex-employees, random metalheads with teased hair and voluptuous female customers. It’s hard to picture Pearl Jam playing anywhere but an arena, but a photo of Pearl Jam hung in there, taken in October, 1991 on their first tour, opening for a newly signed band called I Love You, who no one remembers. My favorite photo featured Franco standing beside a ghastly Perry Farrell from Jane’s Addiction, who looked grim and confused by the photoshoot. People called the collection The Wall of Fame, but fame eluded many of these musicians. Franco probably forgot many of their names eventually.

Franco got into the music business by accident. He came to Phoenix for a wedding and tried to buy a restaurant with a business partner. When the owner rejected their offer, the realtor brought him to a rock club that was up for sale. “They had this punk band the Urge playing there,” Franco told the Phoenix New Times, “and the kids are smashing their heads against the poles. So I’m going, ‘What the fuck is that?’ And they go, ‘Oh, that’s moshing.’ And the place was packed. The only thing I was watching was the register ringing. I didn't know anything about the rock ‘n’ roll scene at this point, but I knew that every place else on a Sunday was dead.”

The Jar had long history of hosting ’80s punk shows and underground bands. Phoenix’s pioneering Meat Puppets played there all the time, years before Kurt Cobain’s endorsement helped transform them from a weird local band to alternative staples.

They even celebrated the release of what became their immortal, 1985 masterpiece Up on the Sun at The Jar.

By the ’90s, The Jar hosted too much hair metal for it to have the cachet of The Blind Pig or Chicago’s Cabaret Metro, but Franco did build it into one of the most popular stops on the Western tour circuit. He courted bands aggressively, often poached them from other local venues. He kept free bottles of Aqua Net hairspray in the bathrooms for metalheads and he had a great PA system, what show flyers called “THE BEST SOUND IN TOWN featuring the Renkus Heinz Sound System.” The Jar’s old squigly font became aggressively sharp during the metal years, with the tip of the J pointing like a lightning bolt on flyers.

Many local metal bands relied on the Jar to find an audience, and Franco fed many touring bands, sometimes helped them book hotels. and flew them to Phoenix. “The first thing, as soon as they get out of the bus,” Franco said, “cold water, beer, and food. They don’t even have to ask for that. Then pasta and a nice salad.” A salad—I bet many of those bands hadn’t eaten vegetables in years. When Tiny Tim played The Jar, he slept at Franco’s house. When one band’s van broke down on the way to Phoenix—it was either an unsigned Stone Temple Pilots or a now-forgotten 3 Doors Down—Franco paid for repairs so they could make their gig. Franco booked so much music that he eventually opened a second club just for alternative bands. Located in a strip mall at 5029 N. 35th Avenue, he called it The Underground. That’s where Jane’s Addiction played. Among musicians, Franco had a mixed reputation for being either an ally or a cheat, because depending on who you asked, Franco frequently paid bands less than he promised.

“We were in this crummy toilet of a club in Phoenix,” Jane’s Addiction’s first manager, Charley Brown, remembered, “not the Mason Jar—but it was the same slimeball of an owner, trying to expand his empire by opening another filthy little public sewer with a stage and a bar. Nobody knew who we were. There were like ten or twenty people. So, now this guy wants to stiff us on our guarantee, the lowest form of bottom feeder life in club or concert promotion. That happened quite often at the beginning, and so tonight I’ve had it, tonight I’m gonna try out alternative collection techniques. I decide to raise my voice. I’m like hollerin’, shouting real loud at this tiny little thing, this creepy little troll, like under five feet, who now starts blowin’ this fuckin' whistle, and now these two Neanderthals grab me and hold me, and he starts strangling me and then he calls the cops. And the cops are gonna arrest me for assault and I’m like, ‘See these hand marks around my neck?’ They literally ran us out of town, and because he was in with the cops he didn’t have to pay us.”

“One tour we’re playing some dive club in Phoenix,” said Jane’s singer Perry Farrell, “trying to get paid while this guy is choking our manager and pulling a gun on him. Next, we’re selling out Madison Square Garden.” That was life during the time underground was going mainstream. To save money that week, Jane’s camped in the desert while driving east to New York. Clearly Franco took his photo with Perry before the shows.

Before retiring, Franco denied the charge. “I’ve not seen one national band say I never paid them,” he said. “None of those bands would’ve played here if I fucked even one of them, ever.”

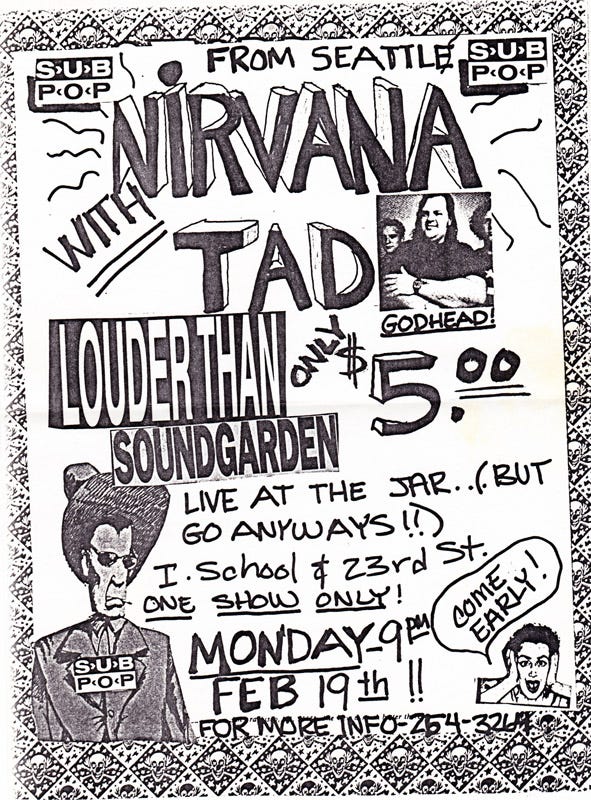

Despite Franco’s mixed reputation, young bands were so used to working for peanuts and sleeping in their van that they kept playing places like The Jar. By booking multiple shows a night, both all-ages and 21-and-over, and selling 75-cent Kamikazes, Franco made a killing. Legends like Bo Diddley, The Ramones, and John Lee Hooker played the same cramped stage as local hair bands like Tuff and Flotsam and Jetsam. As hip hop and alternative music got more MTV and radio play, The Mason Jar made a business from booking those bands. Nirvana played there in February, 1990, still touring for Bleach.

Tool and Helmet, Love Battery and Quicksand, Biggie Smalls, and Tupac Shakur all played there. England’s pioneering band The Manic Street Preachers booked the final show of their 1995 U.S. tour at The Mason Jar, but they had to cancel the tour when their guitarist and lyricist Richey Edwards famously disappeared. But The Jar’s metal reputation was so embedded by the early ’90s that the Nirvana flyer said the show was at the Jar, “but go anyways!!”

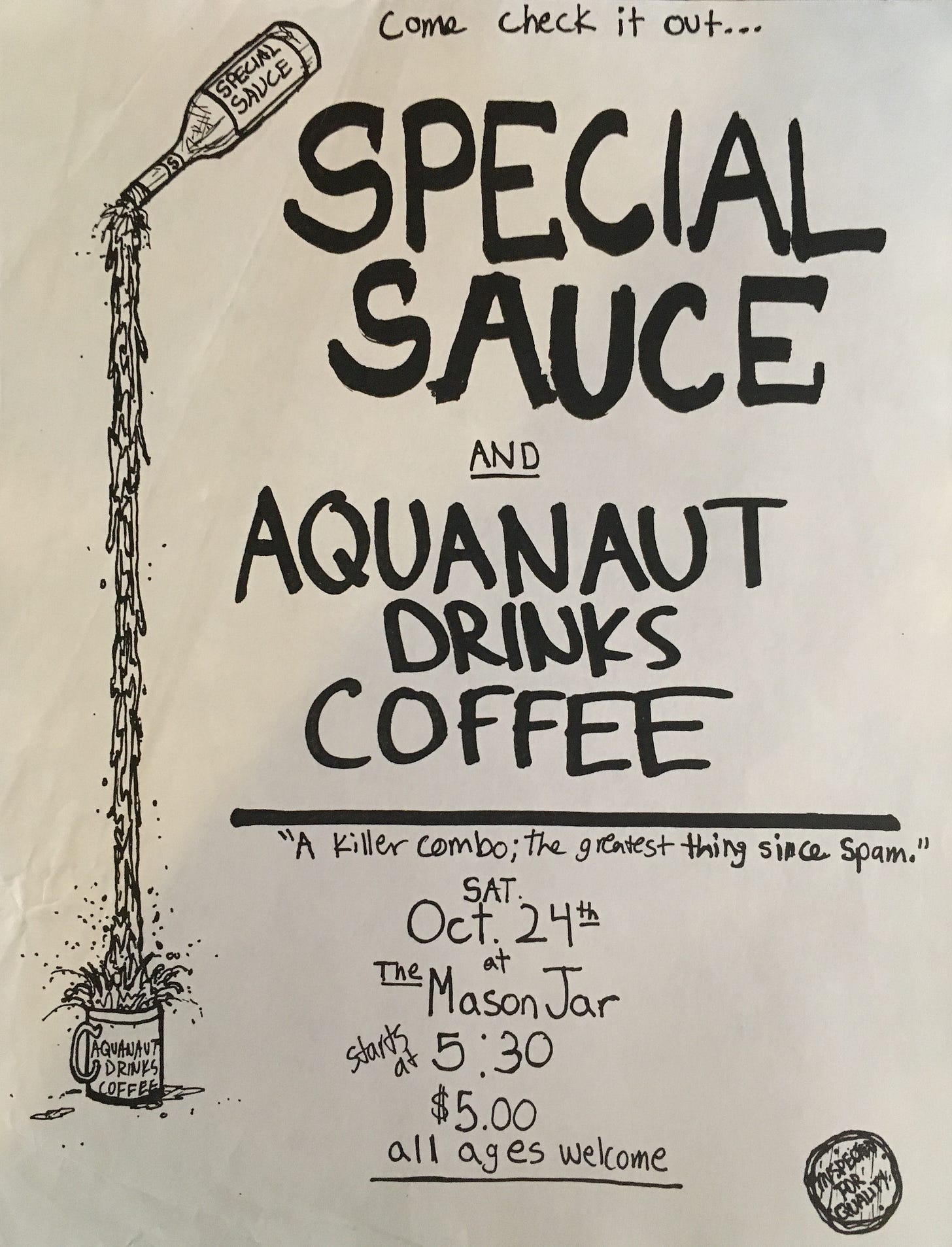

During my junior high school year, a few classmates asked me to join their band, mistaking my long hair and drawing skills as proof that I had whatever it takes to be frontman. I did not. Our band Special Sauce played The Mason Jar three times during our senior year. We sucked and I was mortified in front of all 10 or so people, but by then, I knew my feet stood on hallowed ground. I knew that we loaded our gear through the same door where Cobain had rolled his BFI Bullfrog 4 X 12 cabinet amplifier three years earlier. I knew that I stared at a mostly vacant floor from the same stage where Maynard from Tool stared down the rowdy audience in a club his band soon outgrew. Part of me is grateful no record exists of my stagefright. Another part of me wishes our band had recorded our Jar performances. I would love to see what color flannels we wore, and how I stood as still as an obelisk for way too long before finally relaxing enough to swing around my blonde hair. These were the biggest shows we played, and thankfully the last.

Performing made me so nervous that the experience only conjures a few hazy images. Nerves and weed seem to have inhibited my memories. I thought we’d only played The Jar once. The flyers tell a different story. Unlike good local high school bands like Aquanaut Drinks Coffee and Heavens 2 Betsy, formed by my middle school skater friends, I didn’t have stage presence. I was a listener. I belonged in the audience, or behind a camera recording shows, close to the stage, not on it.

“Hi,” Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic told The Mason Jar crowd, “we’re a Mötley Crüe cover band.” I wish I’d seen that show. He’d clearly browsed the walls.

It’s strange to look back on your youth from mid-life and see all the historic musical moments that happened so close to you, while you were obliviously riding your bike through a park or writing Valentine’s cards to your disinterested crushes. Or worse: only getting to see concerts on TV because you where 12, or your parents were super religious, or you lived somewhere that few bands toured. But that’s how it went for me and millions of other kids who came of age in the ’90s. Thankfully, the underground music that played on college radio stations was circling closer to us each month, getting more widely circulated through mainstream media channels, and eventually, one way or another, it would reach us. Before long, we’d dye our hair blue, put on baggy ass clothes that made our parents cringe, and start seeing shows at venues wise enough to let in kids under 21.

Unbeknownst to me that spring of ’89, Mother Love Bone’s one and only tour passed through my hometown and headed west to Los Angeles, where they played two nights at the Club With No Name in Hollywood on April 28. Someone filmed one of their sets. Wood was on fire, always the consumate performer, prancing and baiting the audience with lines like “Love rock awaits you, people!” Not everyone was amused. “The first night, Dogs D’Amour,” wrote Goldmine, “obviously fed up with Wood’s onstage antics, positioned their equipment to ensure that he would be unable to move around as much as he normally did. Wood took his revenge the following evening. Using a wireless mike, not only did he take over the stage, he now had the entire club at his disposal.” No one could slow Andrew Wood but himself.

On their way home to Seattle, they played San Jose’s Cactus Club on May 1st. As someone had done in Rhode Island, someone recorded the San Jose show through the soundboard, and a few songs leaked onto bootlegs, where all the kids too young to know could one day listen to what we missed. Lord knows I did. I listened so much I even memorized Wood’s stage banter.

When they arrived home to Seattle, they ended their tour with a show at The Oz, opening for the increasingly popular Alice in Chains. No one recorded that show except a newspaper review. “Looming larger than life, center stage, was Dallas fan, Andrew Wood, sporting a Cowboy’s jersey and the ever present chartreuse green,” wrote local journalist Michael Browning. “Jeff’s bass intro filled the hall with as much power as any band who plays the Coliseum, and you can bet (your sweet ass) that these guys are arena-bound.” Browning called them “a must-see event!” Opportunities were dwindling.

After the show, tour ended and shrunk the scale of daily life. They played a few local gigs, including Bumbershoot Festival. They tinkered with new music, and they spent the summer waiting to see if PolyGram would fund a full-length album. Drummer Greg Gilmore was stunned “how painfully strung out the whole process seemed to be.” Wood was also using heroin.

After a tense wait, the band embedded themselves at the Plant studio in Sausalito, California in September, to record their full-length debut, Apple. “Gilmore remembers finishing his contribution in five days,” Goldmine wrote, “spending the next two months riding his mountain bike while the rest of the band continued slogging away in the studio.”

The band completed Apple in Seattle. It got mixed in England. They shot a very expensive, unsatisfying video for “Stardog Champion.” And Wood spent the last two months of 1989 in a rehab facility, working to overcome the heroin dependence that would take his life. I spent those same months adjusting to my first year of high school.

If people made a fuss about the end of the ’80s, I was too young to notice. The dawn of a new decade was another New Year’s Eve to me. As a high school freshman, I had bigger things like friendships and music on my mind. Behind the scenes, influential, ambitious people were plotting world domination.

In March 1989, before Grunge broke, Sub Pop flew an English journalist named Everett True to Seattle to write a story for The Melody Maker. Using one engineer for their records—the great Jack Endino—and one photographer—Charles Peterson—the label packaged the Pacific Northwest’s music with a uniform sound and uniform look that appealed to consumers but didn’t exist in reality. That’s part of what made the label genius. They created a label identity that was a popular brand but seemed subversive, and they marketed the underground to the world. That’s part of what made “Grunge” a fiction, and why people still snarl at the term. But True saw the narrative that Sub Pop cofounders Jonathan Poneman and Bruce Pavitt were pushing. Or in Pavitt’s words, True “was a brilliant enough guy that he could piece together a story that essentially sold the world on Seattle.” That line is classic Sub Pop smoke and mirrors, and I’m grateful for it. Because that simple magazine story, and the label’s global ambitions that engineered it, set the stage for the entire decade to come.

In 1991, piggybacking off the media hype around Seattle’s pioneering band Mudhoney and the naked self-promotion of Sub Pop’s owners, Nirvana would score a breakout hit with their song “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which would finally help turn the volume down on commercial heavy metal, put all eyes on Seattle, and usher in the so-called Alternative Era. Then the stereotypical ’90s had truly begun. For me, the ’90s started not with Nirvana, but with Mother Love Bone.

Like eating your favorite food every night, listening to one band exclusively will ruin their music.

By the time my high school sophomore year started in August 1990, I was burning out on synth. Three of Violator’s four singles had been playing incessantly on MTV and radio all summer, and when the last single, “World in My Eyes,” started rotation that September, I’d listened to every DM record a thousand times too many, producing the musical equivalent of a vitamin deficiency. I needed guitars, drums, variety, anything else. I missed the urgency of guitar-bands like The Cramps. I’d been jamming The Cult and Fishbone a lot, and the Chili Peppers’ The Uplift Mofo Party Plan, since they sang “Me and My Friends,” which was a fitting anthem for the bond my friends had—this before I started to hate all their macho sex rap crap and quit listening—and that led to The Sundays’ pop perfection Reading, Writing and Arithmatic. Eventually, my tastes flipped from DM back to rock ‘n’ roll in time to catch the cool underground stuff that older siblings’ kept feeding us. But it took a while.

As the world awakened to once underground music in the early ’90s, my friends and I did, too. Not because we were so cool that we were ahead of the curve, though we kinda were. We awoke because we were products of the wider world. We were the target youth demographic. We were consumers of mass media, the audience for the marketing messages, and the messaging worked.

Many people can pinpoint the song or band that changed the direction of their life. Michael Jackson turned music writer Jessica Hopper into an adult listener with her own tastes. “...Thriller had taught me what it meant to have music be your whole life, to be a devoted fan; Thriller was the first album that was all mine, not my parents’,” she wrote in The Village Voice.

When Kurt Cobain grew up in small working class Aberdeen, Washington, he was surrounded by people he considered rednecks who listened to hair metal, Sammy Haggar, and Led Zeppelin. Then he heard The Melvins play a free show behind the Thriftways supermarket where lead singer Buzz Osborne worked. “[T]hey plugged into the city power supply and played punk rock music for about 50 redneck kids,” Cobain told Option magazine. “When I saw them play, it just blew me away. I was instantly a punk rocker. I abandoned all my friends, ’cause they didn’t like any of the music. Then I asked Buzz to make me that compilation tape of punk rock songs and got a spike haircut.”

For me, the ’90s started when my friend JR played me Mother Love Bone.

When you came of age before the internet, you inherited music from cooler elders. My Depeche Mode-loving classmate Laura Bond first heard DM playing through her older brother’s bedroom wall. My close friend Alex discovered Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love when his older brother turned him on, though I was still too deep into DM to receive Alex’s rock message. Chris’ sister took him to see Fishbone and that Jane’s show when he was a kid, and played him Meat Puppets before I’d ever heard of them. Underground music was generational, a form of tribal knowledge.

After an older dude turned JR onto Mother Love Bone, he passed that Grunge gateway drug to me. My edges were hardening and tastes growing darker, which is often the case with adolescents’ moods as their parents’ influence wanes and they build a universe defined by friends and hormones. Eventually I removed the Depeche posters from my walls and tucked the t-shirts into a drawer. I stored my bootleg records off to the side of my record player, as I collected new records from Jane’s, Fishbone, The Wonder Stuff, and Soup Dragons. It took a few coats of paint to cover my DM wall-art, but eventually, those disappeared too.

After Mother Love Bone had recorded Apple, I started listening to their Shine EP on cassette the way I used to listen to DM: constantly. I liked the band’s glamorous, sensitive take on rock. They had fast songs, powerful riffs, and catchy melodies, but their starry-eyed lyrics and spacey guitars offered something new and melancholic, something that felt both rocking and vulnerable, which felt different than rock bravado and punk posturing. In their lead singer, Andrew Wood, I sensed the same soft gender norms that had attached me to Depeche Mode. This was especially apparent in an eerily beautiful slow song at the tape’s end.

Called “Chloe Dancer/Crown of Thorns,” Wood starts the ballad by singing over a spare piano melody. When the rest of the band comes in, they play quietly for a while, letting him tell his sad story.

It’s a broken kind of feeling

She’d have to tie me to the ceilin’

A bad moon’s a’comin’, better say your prayers, child.

The song felt haunted, chilling in its simplicity, like it came from somewhere desperately sincere.

Talking to my altar

Say life is what you make it

And if you make it death, well rest your soul away.

Wood wrote it about the way heroin was destroying his relationship with his fiancé, Xana La Fuente. “This song is about a relationship ruined by drugs,” La Fuente said. “He wrote it about our near breakup, and how I tried to control him and the drugs—hence his allusion to being tied to the ceiling.”

I knew nothing of drugs back then. I’d never consumed a single one. I’d smoked nasty skinny cigarettes stolen from a friend’s mother, but I’d only gotten drunk twice, and it was horrific. Even without a shared experience, Wood’s emotional intensity shook me.

After another verse and chorus, the band goes quieter during an eerie instrumental breakdown that builds toward a final crescendo. The breakdown feels serene, like an early morning on Puget Sound, where fog drifts over the still water, and a spirit hangs in the air. Tension builds. You know something’s coming. When it does, the guitars and drums kick in, riffing with a spacey guitar soloing beneath it all. Rolling Stone listed this as one of “The Fifty Best Songs Over Seven Minutes Long.” As an adult, I could add many songs to that list. As a kid, I loved the ending so much that I’d rewind my tape over and over just to hear that part.

“Crown of Thorns” had such commercial potential that the band put a shorter version on their debut LP Apple, too. But the same force that fueled this masterful song was the same force that tore the band apart.

Backed by major label money, they had a manager now, big press opportunities, and big career ambitions. “There has never been a singer in Seattle music history that wanted to be a star more than Andy, and had the charisma and gregarious nature,” Rocket editor Charles R. Cross said, “it was going to happen for him.”

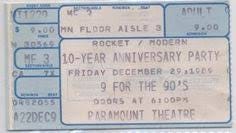

In December, Love Bone played the Paramount Theatre as part of a show celebrating the tenth anniversary of Seattle’s influential The Rocket music magazine. The epic line up included Girl Trouble, Beat Happening, The Young Fresh Fellows, The Fastbacks, The Walkabouts, and The Posies. Imagine Beat Happening playing with Love Bone. What a strange combination. What a perfect embodiment of the old Northwest’s musical variety. The only evidence I could find was this stub.

Someone recorded Love Bone’s energic January 1990 show at The Vogue in Seattle. “Don’t you die on me, boy,” Wood sings two minutes in, “don’t you die on me.” When he tells the crowd “Love is all you fuckers need!” it feels like he was trying to convince himself.

Wood worked up the crowd before “Holy Roller.” “We ain’t seen Seattle since September. And I tell you, I been out learnin’ about myself and shit. …I’m just tellin’ you people, it’s the ’90s now!” During the song’s big arena rock breakdown, he told them, “Going into 1990, it’s the age of monogamy and trust. …First of all I want to thank Green River for breaking up and giving me my boys on the bass and guitar.”

They’d only play two more shows.

On March 15th, Michael Browning interviewed Wood for Rip magazine. Browning loved the band so much at The Oz that he bought his first Seattle band shirt: the Shine EP cover art with the words “Do What You Do.” He even made a homemade sign that said Chloe’s Crown, and when he tossed it on stage during their Bumbershoot show, Wood set it on his keyboard for the audience to see, then kicked into “Chloe Dancer/Crown of Thorns.” That’s how permanent fans are made. “I was already deeply in love with the man and his message,” Browning later said. “Love Rock awaits you people!” I knew the feeling. During their conversation, Wood talked about songwriting, the upcoming album Apple, and his recent 28-day stint in rehab. Wood spoke with the kind of confidence you could mistake for permanence.

Anrew Wood: Yeah. Still though, it’s a total struggle. When you first get out, you’re on this pink cloud, and it's pretty easy. After a while things start getting more real, and you have to just stay straight a second at a time.

RIP: Do the other guys in MLB still get stoned?

A.W.: No! That’s one lucky thing about this band. I was the druggy until I went in for treatment. We’ve got some people in the band that I don’t doubt are alcoholics. The day Bruce quits drinking will be the day monkeys fly out of my butt, like on Wayne’s World. Luckily no one was into the drugs as much as I was, so I don’t have to worry about them staying stoned, even though I’m not doing it anymore. Ever since I’ve known Stoney and that's been years, he's never smoked pot.

RIP: Stoney?

A.W.: I know, with a name like Stoney. It’s just his normal name: Stone. They all enjoy their beer. God, that's the thing: Back when I was taking all those drugs and everything, I thought the other guys were so damn boring. I thought, What do these guys do for fun?

RIP: Will this upcoming tour present any problems for you, like temptation?

A.W.: We all decided that on the upcoming tour there will be no alcohol at all on the bus. If they want to drink, they'll have to do it inside the clubs.

RIP: Is there any particular member of MLB that you seem to connect with the best?

A.W.: It’s weird, ’cause it fluctuates. Sometimes I feel like me and Stoney are a team, partners in crime. And then me and Jeff have a lot of the same musical interests too. We’re both kinda jocks in a way. I’m a video jock, whereas he’s an actual jock. Then me and Greg are both Capricorns, so we get along well. Besides practicing five times a week, none of us spend that much time together.

RIP: Maybe it’s better that way.

A.W.: Yeah. I mean, we’ll be spending a lot of time together real soon.

The next day the band met with someone to manage their upcoming tour in support of Apple. This candidate had experience helping musicians stay clean on the road. Wood skipped the meeting and told the band he trusted they would choose the right person for the job. Later that night, La Fuente left five frantic voice mails on bassist Jeff Ament’s phone, telling him they were rushing Wood to the hospital after a heroin overdose. She’d found his body in their apartment.

Apple would be the only full-length record they ever put out. Wood died in the hospital on March 19, 1990, at age 24, a few days before Apple was supposed to come out. The label postponed Apple’s release until July, 1990.

Everyone hears this version of Wood’s story. What they rarely hear is La Fuente’s role in it. It was La Fuente who bought Wood’s food and clothes and paid the rent during the years that he wrote songs, got famous, and got addicted to heroin. It was La Fuente who found Wood’s body. “I was the one working for years to make sure he could stay home and write,” La Fuente wrote years later, excorating Cornell for not giving her royalties or any of Wood’s possession. “I was the one who didn’t drink with him, didn’t smoke pot with him and certainly did not shoot heroin with him…Everything he wore, including his Laker’s Jersey I paid for.” Behind so many successful male artists is a woman working hard behind the scenes or being kept behind it.

As the band became popular posthumously, “Crown of Thorns” became their signature. Cameron Crowe had used it in his 1989 romantic comedy Say Anything. When Crowe wrote his next movie, Singles, around the burgeoning Seattle music scene, he featured the song again. By the time the song appeared on Singles’ legendary soundtrack in 1992, Woods’ city had become the epicenter of cool. Sub Pop had sold Seattle’s musical subculture, and the idea of subculture, to the world. Kids in desert cities like me knew where Seattle was located, even knew the names of its neighborhoods and tourist attractions, without setting foot there. Now Hollywood and big corporate labels wanted to sell it, too. Everyone was clambering for that thing stupidly labeled “Grunge.” Love Bone’s album Apple had received rave reviews and fanfare, which fed the Seattle buzz.

And in death, Wood’s sad ballad became his eulogy, a relic from old Seattle before the corporate record companies and Grunge copycat bands descended, a statement about the struggles that would end many Northwest musicians’ lives. The song spread his legend so far from sleepy Seattle that people in Spain, Russia, and Japan eventually sang the lyrics without understanding their meaning, and some of Woods’ friends and bandmates Stone Gossard and Chris Cornell became more famous than they could handle. Wood would have made it big, too, if he could have held off longer. As he sang, “He who rides a pony must someday fall.”

It reads kinda corny, but the way he sang it was beautiful.

All that Seattle hype came later. To us in 1990, Mother Love Bone was just another cool new band that emerged from out of the ether, a badge to wear to let other high schoolers know we weren’t like them. Our tastes were underground, even though my board shorts, bangs, and beaded necklace made me look like a dork. (Jeff Ament’s description of himself in Pearl Jam’s early days captures how I felt about myself: “At the time, I don’t think I looked like a rocker, I looked like a dumbass.”) This was a brief period of time before Singles and “Smells Like Teen Spirit” carried the message to everyone else, and pushed listeners like us—cool outsiders who turned out to be just another kind of consumer—to distance ourselves from his glammy proto-Grunge band with embarrassing hairstyles and clung to Gish and Rock for Light instead. But for a spell, JR and I had Love Bone eyes, minus the teased hair. Love rock awaits you!

Although Mudhoney, Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden were the bands that put the Pacific Northwest on the map musically, Love Bone was the band that started the region’s rise on a dark destructive note. As a listener, Wood was my first heroin casualty. His death set the frame around the drug-filled decade to come, an era of heroin abuse that affected so many musicians that their deaths, arrests, and recoveries were like a mini-series on MTV News.

Baby Boomers have said that if you remember the ’60s, you didn’t live through the ’60s, and I’m sure that’s true. But for many of us Gen Xers, the same can be said of the ’90s. Youth culture always seems to tangle itself in substances, from the Beats to Be-bop, the ’60s Hippies to the ’70s punks, but the ’90s had it bad for heroin, ecstasy, and LSD. What acid was to the ’60s, cocaine was to the ’80s. For whatever reason, heroin was everywhere during the early ’90s. It probably had to do with economics, the invisible forces of drug cartels’ production, marketing, and distribution. (Gibby Haynes attributed it to the business-savvy Columbian suppliers.) But anyone paying attention to underground music saw how hard it danced with dope. First Andrew Wood died. Then the infamous GG Allin overdosed in 1993 a month before The Wonder Stuff’s bassist Rob Jones. In 1993, the Gin Blossoms’ hit-making guitarist Doug Hopkins took his life, though he was an alcoholic. In 1993, a speedball ended actor River Phoenix’s life outside the Viper Room, while his buddies Gibby Haynes, John Frusciante, Flea, and Ministry singer Al Jourgensen played a show inside. Their super-group P was in the middle of their song “Michael Stipe,” where Haynes sings “I’m glad I met old Michael Stipe, I didn't get to see his car. Him and River Phoenix were leaving on the road tomorrow.” Kelley Deal of The Breeders got arrested for heroin possession in 1994, while working on the follow-up to band’s popular Last Splash. Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain took his own life and Hole’s bassist Kristen Pfaff died in ’94. Blind Melon’s singer Shannon Hoon died in ’95, though that involved cocaine. Jourgensen got arrested for heroin posession in ’95, but he kept using for nearly twenty years. Heroin took the life of Sublime’s singer Bradley Nowell and Smashing Pumpkin’s touring keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin in ’96. The year after his friend River Phoenix died, the Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante was so strung that an LA newspaper called him “a skeleton covered in thin skin.” He stayed strung until ’97. By 1997 dope was so epidemic that Portland, Oregon’s Dandy Warhols sang “I never thought you’d be a junkie, because heroin is so passé.” But heroin still claimed Alice in Chains’ talented singer Layne Staley eventually (“Faster we run / And we die young.”) And Nine Inch Nails’ singer Trent Reznor nearly died in a London hotel room after snorting China white that he mistook for coke. For all the lives that heroin took, many musicians managed to save themselves: Blur singer David Albarn: Smashing Pumpkins’ drummer Jimmy Chamberlin; Everclear singer Art Alexakis; Pantera singer Phil Anselmo; Dave Gahan of Depeche Mode; Gibby Haynes of Butthole Surfers; Trent Reznor of NIN; and Cris Kirkwood of Meat Puppets.

People associate the ’90s with flannels and baggy pants, but sadly, drugs also defined and destroyed the era as much as bad fashion. They were so insidious that nearly three decades later, some of us still see their effects. Friends who couldn’t stay away from drugs have died. Decades of drinking have ruined classmates’ health. Smokers who can’t quit now look dried out. In midlife we tell stories about our fallen friends. Their faces in old photos makes us cry. We listen to dead musicians and wonder what they could have been. Then there’s us Gen X parents who wonder how to explain to our children why we “experimented” with drugs but they shouldn’t. Gen X was the first generation to play video games and arguably the last to record radio broadcasts onto cassette tapes, but we weren’t the first or last to lose so many people to drugs.

Heroin eventually killed two of our high school friends. Pills and alcohol killed JR, and heroin led to my own arrest and probation by 1999. I’d made it to the end of the decade. I still wish we’d headed Woods’ warning: “The future was in my hands / Till I washed it all away.” Some of us needed to ride our own ponies.

When I hear Wood’s lyrics to “This Is Shangrila” now, I think not of Wood, but JR:

I’m a football who knows who and I don’t believe in smack

So don't you die on me, babe, don’t you die on me

’Cause love is all good people need

And music sets the sick ones free

Fans wonder about all the music Wood would have made had he lived.

I wish we could have reached JR.

Wood died as our innocence was ending. Before we started spending nights drinking the beer that would lead to darker places, my friends and I spent nights making mischief in our neighborhood: setting off firecrackers; sawing shotgun shells in half to ignite the gunpowder; sneaking around a dark golf course just because it was dark; watching horror movies. During the day, we rode bikes, hung out at air-conditioned malls, played Nintendo at home and standup games at video arcades, and we took pizza breaks at Peter Piper during marathon sessions skateboarding a concrete flood control device called The Wedge. Then we discovered urban life, meaning, we discovered where girls hung out and live music played: On a commercial strip called Mill Avenue.

Mill was named for the old Hayden Flour Mill on the north end of the street. It dated back to 1874, a time when a ferry, named Hayden’s Ferry, had to shuttle passengers across the neighboring Salt River because no one had built a bridge. The mill still stands, but a sprawling university district has grown around it, and it came alive on weekends.

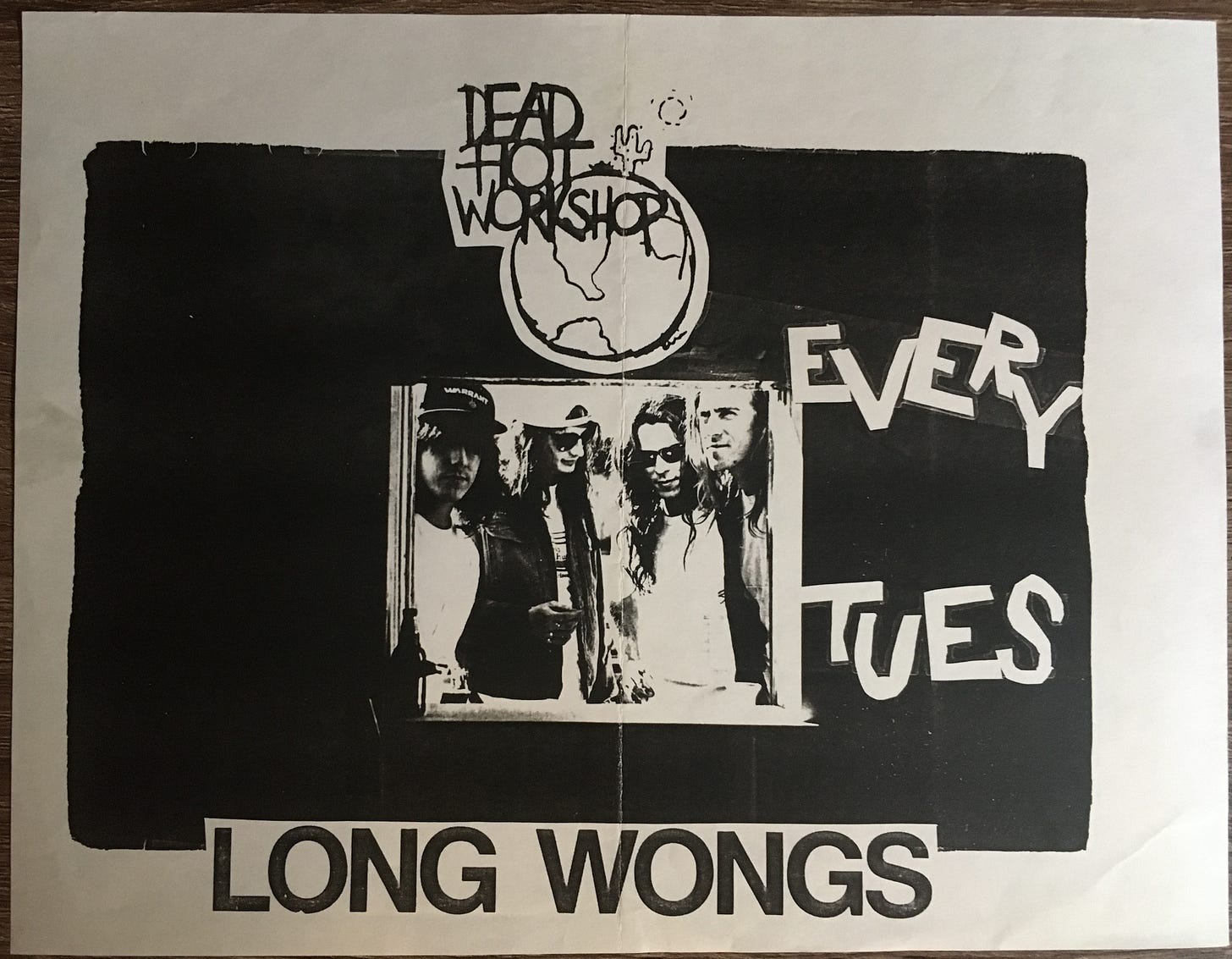

Old enough to smoke cloves but too young to drive, my high school friends and I used to have our parents drop us off in downtown Tempe on Friday and Saturday nights so we could walk Mill Avenue. Without a traditional downtown, Phoenix nightlife took other forms in its satellite communities. This spot was bohemian. Hippies made drum circles on Mill Ave’s median. Artsy kids played music in nearby flop houses, and college kids stumbled drunk from sports bars. Mill had a headshop and bookstore. Wandering up and down Mill for hours, past the coffee shops and cafes and loud bars that stunk of cigarettes, JR, Jason, Nate, Jody, and I would rest on planters and strike a pose. We’d shop for records, eat greasy food. We walked like cars in the 1950s cruised: back and forth, back and forth. One night one of my brothers or uncles spotted us on the street, selling beaded jewelry that we made. No one bought any. Since we always failed to talk to girls, we’d stand behind the big window at Long Wong’s Hot Wings to watch bands play. The little club’s north window looked right onto the inside stage, giving you the drummer’s view of the little packed place, and a view of the small audience’s faces. Since we couldn’t attend intimate rock shows like this, this was the next best thing, a literal and metaphorical window into the adult music world.

Your teenage hangout might not have been the back of a club, or a commercial street, but surely you had one. And I’m sure you had your own gateway drug music that led you to the music that changed you the most. Maybe it was The Cure. Maybe Madonna or TLC. This window as one portal to adulthood.

During the early ’90s, Tempe fixtures Gin Blossoms, The Pistoleros, The Refreshments, and Dead Hot Workshop regularly played Long Wong’s. People referred to them as “bar bands” and “roots rock.” I didn’t like how any of them sounded, but I liked how live music looked, and I wanted in. Nirvana’s success in 1991 eventually sent record execs searching the world for the next big thing, and some locals said that these were the Phoenix bands who would make it big. Everyone was looking for the next big thing. Record labels threw ridiculous money at the most inexperienced musicians. Bands got hopeful. They groomed themselves for fame. Some bands had only formed months earlier. In the early ’90s, hype went as far as calling Tempe “the next Seattle.” Hype said the same thing about Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood, where the band Veruca Salt had played their future hit “Seether” in tiny bars. Hype said it about Tucson, Austin, Chapel Hill, Raleigh, Athens, and Minneapolis. “Record executives are also looking at Halifax, Nova Scotia, a five-college town with dozens of hometown bands,” Time wrote in 1993, “as well as Portland, Oregon—Gus Van Sant-land and a grunge Mecca in the making.” If it could happen in Seattle, couldn’t it happen anywhere? You could see how people would want that in Tempe. Mill was so alive. We wanted to be a part of that. We hung out in malls, too, but the mall wasn’t the same. No matter what else we did there, we always ended up back at the Long Wong’s window at the end of the night, watching. It was so innocent. It was my favorite part of Mill. Innocence didn’t last.

In 1992, Gin Blossoms enjoyed brief fame with their songs “Hey Jealousy” and “Found Out About You” and quickly became a small source of hometown pride without maintaining their national visibility. In 1993, Nirvana invited Phoenix’s Meat Puppets to play on their MTV Unplugged set, and introduced the world to our beloved Kirkwood brothers. In 1997, Tempe’s Refreshment went from playing Long Wong’s to providing the iconic instrumental theme song for the popular cartoon King of the Hill, which is a song they used to play at soundcheck. Tempe never became Seattle, though.

After JR started driving, we went to Mill less frequently and started hanging out at peoples’ houses, occasionally drinking beer. Then we started seeing tons of rock shows, and eventually, going to parties when people started throwing them. We didn’t need parental permission to see bands on weekends, and we had the wheels to reach venues now.

As Tempe got slick and redevelopment changed the face of Mill Avenue, tall shiny builds got built all around Long Wong’s, boxing it in. Short and squat, it was the last piece of ’90s Bohemian Tempe. “It sticks out like a sore thumb. It’s the ugliest building on the street, but I love that about it,” Dead Hot Workshop drummer Curtis Grippe told a local paper. “When that place comes down, so will that era.”

Long Wongs closed in 2004 and quickly got demolished.

“It’s the crux and the heart of our little music scene,” Gin Blossoms singer Robin Wilson told a local paper. “For a lot of us musicians, Long Wong’s was an anchor to our audience and our peers and for some people, it was an anchor to planet Earth itself!”

And it turns out, I like a few Gin Blossoms songs now. “Found Out About You” is way better than I realized as a kid. Age does that to you. As Arizona record store clerk and writer Fred Mills wrote of the Blossoms’ best music, “Unlike the oftentimes wavering loyalties of friends, lovers, and family members, a sad song will never let you down.”

The Mason Jar building still stands on Indian School, though the club’s called the Rebel Lounge now. I wonder what happened to all of Franco’s photos. I keep my photos in a box.

Going through them, I found pics from Special Sauce’s only group photo session. He did it ourselves up on Camelback Mountain, in the middle of Phoenix, in January 1993. The Mother Love Influence is faint but I saw it. I had us pose on our backs in a circle, just as the band had on the inside of their debut, Apple:

Kids dream they can become their musical gods. Whatever was special about Love Bone’s sauce, we didn’t have it as a band. But it definitely left a lasting mark on us as listeners. And in hindsight, it and all the things young listeners missed could tell part of our story, high up on the mountain, looking down at our lives and the many ways we could live them after high school.