On May 19, 1998, Calexico released The Black Light, its first full-length studio album. The band was a two-piece and their album was a concept album, the concept being a fictional story of life on the Mexican-American border.

Drummer John Convertino had lent guitarist Joey Burns copies of Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy. Both guys were big readers, and those novels helped Burns reimagine the music they were recording as a set-piece with recurring characters, instrumental interludes, and lyrical themes. The storyboarding began when their friend, producer John Parrish, got married at Tucson’s Hotel Congress. “They were in this room,” Burns told Top magazine, “and his wife noticed something under the chair—a bag with a knife—and we picked up on the idea.” They hadn’t planned a concept album. In the studio, they heard how some songs formed a natural narrative progression that Burns called “a beautiful mistake.” “And listening to the initial guitar and drum tracks,” he said, “I just began to hear these western instruments all under one roof. You might hear an overlap every once in a while, but I thought, Why not bring in the lap steel, violin, and mariachi. It seemed to really represent Tucson at the time and reminded me of an updated McCarthy novel where worlds and styles come together.”

Unlike Calexico’s eclectic first record, Spoke, with its low-fi acoustic strumming, vibraphone, and instrumentals separated by snatches of field recordings, The Black Light was a thematically unified piece. Uniquely colored by mariachi horns and a proud Southwestern identity, critics as varied as the Wall Street Journal and Tucson Weekly named it one of the best albums of 1998. It was certainly one of the decade’s most original. At that time, the genre named alt-country was thriving, so the band got filed in the alt-country category. Despite their occasional use of pedal steel guitar, they weren’t alt-country. They were a multicultural hybrid. “We identify more with people like Victoria Williams,” Burns said, “Vic Chesnutt, Will Oldham, from Palace, Smog—the meatier songwriters as opposed to a lot of those bands that sound like like Son Volt and Uncle Tupelo.” No underground bands fused mariachi, jazz, noir, and Ennio Morricone’s twangy vision of the Wild West the way Calexico did.

The Black Light and constant touring eventually propelled them to world renown in the subsequent years. When their breakout album celebrated its twenty year anniversary in 2018, I found myself reminiscing about the band’s early years, and my own.

In the summer of 2018, at age 43, I stood next to the stage at Portland’s Revolution Hall as Calexico filled the old renovated gymnasium with polyphonic rhythms and beams of blue light. My wife bought me tickets for my birthday because she knew how much I loved this band. I’d seen them play since I was a 23-year old college kid back in Tucson. Here I was now, a sleep-deprived father, staying out late, still standing next to the stage, even though I knew our infant would wake us up during the night. Ten musicians now formed the band, and Burns and Convertino remained the core. Their new touring guitarist shredded. Their new album The Thread That Keeps Us was their best in years. Although it covered familiar ground stylistically, this propulsive world music had much more heat than the folk rock they’d released in the recent past. It was the kind of music that reminded me why I’d never stopped listening to their two albums, Spokes and The Black Light, after I discovered the band in 1997. But I still couldn’t help but think of how adventurous those first albums were, and how novel the band was when they formed as a duo in 1996. Back then, while Soundgarden still stomped their big black boots on stage and so-called alternative bands tried to cash in with their best Eddie Vedder impressions, Calexico played xylophones and acoustic guitars, taking cues from mid-century jazz and the sounds of the Mexican-American border rather than the music on MTV. No one sounded like them.

I turned 23 six days after The Black Light came out and I lived in Tucson. My second apartment was down the street from Wavelab Studio where Calexico recorded it in July, August, and December 1997. I didn’t know that at the time. I was just a college kid, and I now regret not discovering the diverse Tucson music scene when I moved to town in 1995.

Many fans view Calexico’s 2000 album Hot Rail and 2003’s Feast of Wire as the band’s golden age, the period where their true sound coalesced and creativity peaked. To me, the years before The Black Light are an equally fascinating phase of their musical evolution. Before The Black Light they performed as a duo. After The Black Light, they expanded to a five-piece, adding permanent multi-instrumentalists to play horns, vibes, bass, melodica, and rhythm guitar, and often a full mariachi band, to bring their albums’ layered orchestral sound to the stage. Their duo phase is one that fans know less, if anything, about.

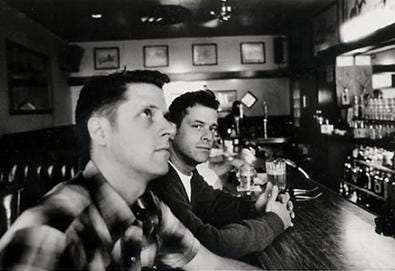

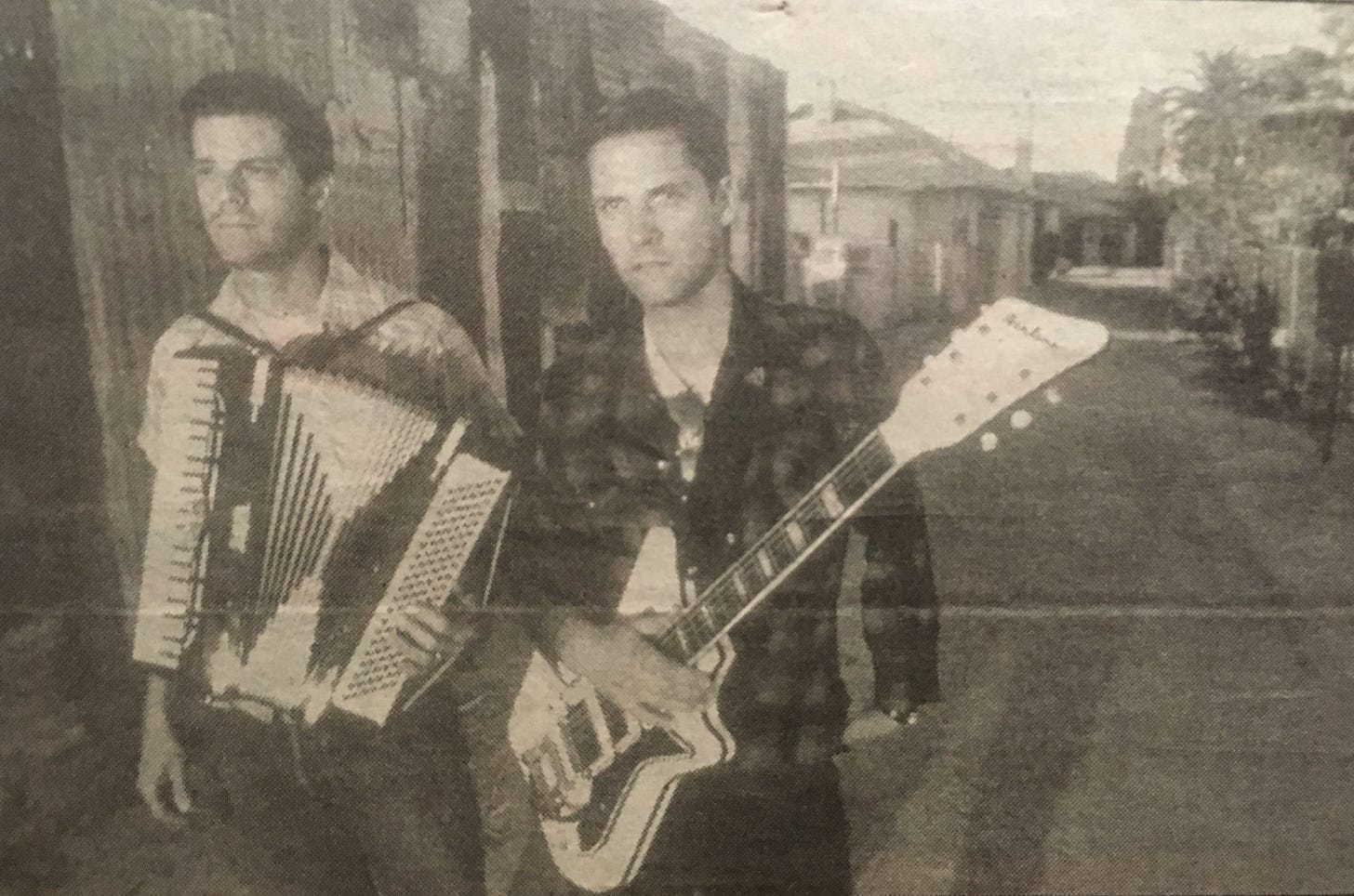

In those early years, Convertino played vibraphone and drums, and Burns played guitar and sang. The setup was elemental, but their two-piece could sound dense and electrified, with Burns’ inventive guitar and effects pedals filling the place of rhythm guitar and bass long before The White Stripes and Black Keys popularized the duo format. The band was a side-project. They didn’t even know whether to call themselves Spoke or Calexico.

They played around Tucson once in a while, at the Bero Gallery, Club Congress, Aroma Café, Berky’s on Fourth, and a small downtown club called the Airport Lounge, at 20 E. Pennington Street. Defunct bands like the Glowworms, Spain, and Phonoroyale opened for them. Sometimes the multitalented Tasha Bundy, Convertino’s wife, played drums so he could play vibes. Sometimes friends joined on piano or violin. They had lots of friends. Tucson had a thriving underground music community composed of eclectic, independent bands like Pork Torta, Doo Rag, Al Perry, Rainer Ptacek, Naked Prey, and the Weird Lovemakers. Convertino and Burns spent most of their time playing in another Tucson band, called Giant Sand.

When Giant Sand toured, frontman Howe Gelb often had the duo perform the opening set or play a few originals as a musical interlude. It helped them test material, and Burns tested himself. “Uh, this is just for fun,” Burns told a New York crowd in 1996, “so, go up there and smoke some pot.” Their music didn’t have its distinctive multicultural identity yet. They didn’t have an album, only a cassette tape they recorded at home, called Superstition Highway, to sell on tour with Gelb. Burns also lacked confidence as a band leader. “You know, I used to be so nervous when Howe wanted me to do some of my songs,” Burns told Tucson Weekly in 1997. “Everything is changing and growing.”

In the words of producer J.D. Foster, Burns was still discovering his musical range back then. “I think that everything he’s learned from the people he’s worked with, he takes with him and he absorbs and kind of turns it on its ear. That’s one thing Joey’s really good at: He’s a student first and foremost.”

Convertino never doubted the depth of his friend’s abilities. “I never really believed that Joey was a singer-songwriter,” he said. “I believed that he was an instrumentalist, a great musician, arranger, melody man. He could learn people’s songs and remember them long after they had already forgotten. But he never really saw that within himself, and I think he’s gotten to that place where he can translate what he’s feeling into words, and really sing it and believe it.” The drummer knew better than anyone. He’d been playing with Burns since they met in Los Angeles in 1990.

Convertino is one of the greatest, most unique drummers underground music has ever known, and his origins deserve telling.

Like many artists, Convertino ended up in L.A. when his band went searching for a record deal, but his career skid to a halt.

Born in New York, Convertino grew up in a musical family. His mother was a singer. His father was a classically trained pianist. They met because of the accordion. “My mom took lessons from my dad,” Convertino wrote, “and they fell in love.” They had a large collection of Broadway musicals, jazz and classical records. Although his father dreamed of conducting a classical orchestra, his university expelled him because of a fake high school diploma. He was the child of immigrants. Instead of composing original scores for a living, John’s father became resourceful. He played piano in restaurants, nightclubs and in the orchestra pit at strip clubs. He tuned and sold pianos, and he taught private accordion and piano lessons at what he called the Convertino School of Music. He even led an accordion orchestra. “They would do classical pieces like Bach,” Convertino remembered years later. “Fifty accordions playing a Bach fugue. It was awesome!” At a young age, John went to work playing accordion on the street while his father collected money in a hat. He later wrote his first song on the accordion, “Per Sempre,” on the Friends of Dean Martinez’s album, The Shadow of Your Smile. His parents’ eclectic taste helped create a son whose varied taste would appear on the records he later made, and he adopted their resourceful, scrappy work ethic.

“When I was a kid I told my dad I wanted to be a drummer,” Convertino told Drum! Magazine. “So he bought me two albums: the original Drum Battle between Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa, and Art Blakey’s Mosaic. He also had a record in his collection by Count Basie, called Basie Jam. I really loved that record and especially Louis Bellson’s drumming.”

The family moved from Long Island to Tulsa, Oklahoma where John’s mother’s family lived, and a local drummer named Mike Bones gave Convertino lessons. “When I was in fifth or sixth grade,” he said, “Mike gave me basic rock beats from Carmine Appice’s Realistic Rock book. Then he asked me to pick out a song I wanted to learn. I chose ‘Roundabout,’ with Bill Bruford. He totally laughed but then he wrote it out for me.” The young drummer liked the open tone of Bruford’s snare. With time, he came to favor a natural sounding drum set and style, warm and intimate, not loud and clangy, and he mixed jazz with the heavier elements he heard in the Ramones, Blondie, Neil Young and Led Zeppelin.

His four siblings all learned instruments. “A house full of music,” Convertino said, “we all eventually started playing together, not unlike the many family singing groups of the ’60s famous or not.” His mother, brother, and two of his three sisters formed a band that made their living playing churches and Christian conventions. They performed gospel, Top 40, and country and called themselves Stand Clear. When Convertino was ten, Stand Clear played their first proper concert: the North American Christian Convention in California, in front of 8,000 people. He’d only taken two drum lessons. “I barely knew how to set my drums up,” he said. “At one point, because the rack tom was sitting on the left side and I didn’t have the spurs set up right, the thing rolled over. It was pretty bad.”

“My parents loved music,” Convertino told Under the Radar, “even though it seemed to me it tortured them at the same time. Mother very much involved herself in church music but continually ran into walls because of the ultra conservative denomination she belonged to, so riding the line between secular and Christian music I think drove her nuts.”

After his mother quit touring to teach singing lessons, Convertino’s siblings started a rock ‘n’ roll cover band. He was in junior high, and they toured the U.S. playing shows at dive bars from the mid-1970s through the mid-80s. They even worked for a year at a ramshackle place in Anchorage, Alaska called Chilkoot Charlie’s. That time was rough. Like so many gold seekers, they eventually moved to Los Angeles in 1984 to use their original songs to land a record deal, but the music industry wore them out. One sister settled down to start a family. Two other siblings started acting. John fell into a series of odd jobs—bussing tables, delivering balloons door-to-door, working as a production assistant on commercials. For a few years he worked for the city, trimming trees and cleaning trash in Elysian Park. This wasn’t the plan. He wanted to play music again.

Before the internet, bands seeking members posted want ads in newspapers like the Recycler. They hung paper flyers in record stores. L.A. was filled with what Convertino called “spandex big hair bands.” “I didn’t want to do that,” he said, but he wanted to do something. When he arrived in L.A. in 1984, he responded to an ad in the Recycler that read: “Drummer wanted, dumb enough to play the primitive beat, smart enough to appreciate it.” That band, The Fugitive Kind, took him to L.A. underground clubs like Raji’s, Club Lingerie, and the Anti-Club—same clubs that Jane’s Addiction started playing at. “One night after rehearsing with The Fugitive Kind,” he said on Instagram, “we went to Gazzari’s on the Sunset Strip to see this band called The Insect Surfers. Being new to L.A., I thought it was just the hair bands that played there,” Their surf instrumentals blew him away, and they happened to need a drummer, so he recorded an album with them, too. He loved ’60s style instrumental rock like the Ventures and Dick Dale. “Those songs have a lot of swing in them and often featured drum solos,” Convertino said. It was hard to find the right group though, and Convertino eventually put down his sticks to figure out his next move.

In the late-80s, Convertino started seeing this weird guy sitting in his car in his apartment building’s parking lot, listening to cassettes of music he’d just recorded. It was Howe Gelb. Although Gelb formed Giant Sand in Tucson in 1980, he’d moved the band to Los Angeles to see what would happen in that land of corporate dollars and opportunity. Paula Jean Brown played bass, Chris Cavacas played keyboard, Gelb sang and played guitar. Their drummer didn’t move to L.A. with them, so his old Tucson friend Tom Larkins played drums until they could find a permanent drummer. “As fate would have it,” said Convertino, “Howe thought that the drummer he needed for the band was right across the hall from him, because there was a drummer that lived across the hall from him, but that guy wasn’t interested.”

When Gelb moved into this building, a year had passed since Convertino had performed music, so in 1988, he told Gelb he was available if he needed a drummer.

Gelb said, “Well, what do you play?”

Convertino told him how his family band’s eclectic sets spanned gospel to country. “I can play just about anything,” he said. “I’m open.” He couldn’t have given a better answer.

Folky, eccentric, spontaneous, adventurous, Gelb was the opposite of a hair band. At true original, he was into everything from Neil Young to honky-tonk, which he merged into a messy, visionary style that was polarizing to those who liked traditional song structures and catchy choruses. Rejecting formulas, he appreciated things of imperfect, fleeting beauty. His unconventional aesthetics could produce music both searing and inspired or formless and forgettable. As one journalist described early Giant Sand, “To say the shows were hit and miss is an understatement, but there was a palpable sense in the room that anything could happen at any time.” What his music sometimes lacked in focus it made up for in freshness and vigor. “I listened to his Giant Sand stuff and it was kind of punk,” Convertino said, “like X, a little revved up, but I was surprised to hear piano in it.” Piano was Convertino’s first instrument.

They started rehearsing, but their rehearsals didn’t resemble any Convertino had experienced. “We’d run through these songs and we’d never really figure out a beginning or an end,” he said. “There would be times when I would be laughing so hard behind the drums. And then he was calling me up to meet him at the studio, and before I knew it we had a record together. It was called The Love Songs.” The album is littered with Convertino’s mistakes. He would point out his errors in the studio, only for Gelb to gently dismiss them. “But right here you can hear where I thought we were heading into another chorus,” John would say. Gelb would tell him, “No, I love that, it’s perfect.” This loose way of thinking made the drummer laugh. It also taught him to embrace improvisation and spontaneity, to look past the individual imperfections to see the larger creative results of jamming and first takes. “[How] he comes up with his music is very in the moment,” Convertino said. “And if you don’t capture that moment it’s pretty much gone.”

“It fell into performance art without having to get naked, or beating yourself up,” Gelb said. “I like when shit goes wrong; I love it when it goes right.” Gelb liked what he called “off-handedness.” “The more you don’t think about things,” Gelb said, “and DON’T think about recording, the more you can actually get what I think are the most honest recordings.” Calexico later adopted this lesson into their own approach: Always keep the tape rolling in studio to record performances, don’t stop for multiple takes.

Bassist Paula Brown and Gelb were married. When they divorced, she split, keyboardist Cavacas pursued a solo career, and Gelb and Convertino explored their new stripped down duo format. It was a chance, in Gelb’s words, “to start all over again.” The elder guitarist was all about experimentation and reinvention, so he embraced the others’ departure as an opportunity to evolve. Convertino absorbed this lesson, too. “I think as a way of being able to survive as a musician,” he later put it, “you have to be able to reinvent what you do.”

The duo played around L.A. When it was time to tour, Convertino turned down a job with the City of Los Angeles to play Europe with Gelb. “I was 26, and my life was completely changed forever,” he said. After Europe, they made the record Long Stem Rant and developed a deep musical intuition. “It was great,” Gelb said. “So free.” Gelb’s unpredictable playing kept Convertino on his toes, moving from thunderous rock to a more intimate style in the span of a few verses. “He would start a song with an acoustic country feel,” Convertino remembered. “Then he would throw his acoustic guitar through a distortion pedal and make it loud. I’d drop the brushes and pick up the sticks. Then he’d stomp on the distortion box and we’d go back to acoustic. I’d drop the sticks and pick up the brushes.”

Music history is filled with guitar-drum duos, especially in Blues. Playing as a two-piece got Convertino listening to Texas legend Lightnin’ Hopkins, who often played with his drummer Spider Kilpatrick and no bassist. The format helped Convertino explore, in his words, “the space between the bass drum hit and snare hit….never mind the hi-hat or cymbals.” For a while, he quit playing cymbals entirely. “[T]hat’s why I love the brushes: You can stay on the snare and hug it, you can play notes that can’t be heard but felt….that got me back to listening to Baby Dodds the New Orleans drummer that never played with brushes, brought the snare and the bass drum together he became the one man parade, made it subtle with the sticks.”

He and Gelb were both excited to have found kindred spirits. “Trying to answer those ads in the paper,” Convertino remembered, “and then realize that the next band I was gonna be in moved into the apartment building. That’s kind of how these things work, I think.”

When they booked a 1990 European tour, they decided to add an upright bassist. Their guitar-based sound was rock but their approach came from jazz. Giant Sand didn’t write set-lists. They arranged their songs and sets differently every night. Any bassist had to be able to play everything from rock to jazz, and to improvise. After Convertino started searching for a bassist, the engineer at Radio Tokyo Studios—Ethan James’s home studio in Venice, where Jane’s Addiction had recorded early on—put him in touch with Joey Burns.

Much younger than Gelb and Convertino, Burns had recently graduated from UC Irvine, where he studied music, and he worked at the front desk at SST Records, answering the phone. Born in Montreal, Canada, Burns’ family moved to Southern California when he was a kid and settled in the scenic Palos Verdes area of Los Angeles. That’s why he eventually named his publishing company Lunada Bay, after the scenic small cove known for big waves and violently territorial surfers. Geography spoke to him long before he wrote songs that spoke for geography. Although his parents didn’t make their livings in music, his was also a musical family. His siblings all played instruments. His mother sang and played piano. She liked like Scott Joplin’s historic ragtime pieces and often sang in Spanish, and the family would gather around her on special occasions to sing together. When his parents traveled, they brought back records and songbooks from Haiti, Mexico, and New Orleans that expanded young Joey’s palate from American Top 40 radio into a multicultural, genre-spanning range. He began on bass.

Like Convertino, Burns also grew up on a diet of jazz and classical, supplemented with heavy teenage doses of punk, pop, indie, hip-hop, and vintage garage rock. He was edacious. But the jazz imparted a particular sense of time and rhythm that differed from the rest. “In jazz, especially, there was a lot more Latin influence that I responded to positively,” Burns said. “Because the bass, being a bass player, is much more free and active and not just playing quarter notes. There’s a lot more division of rhythm, so that really opened me up.”

He played jazz well enough in high school to receive the Louis Armstrong award. When his school band won a competition, the prize provided the opportunity to play the Playboy Jazz Festival on the same bill as Diana Reeves, bass virtuoso Jaco Pastorius, and Ornette Coleman’s bassist Charlie Haden, Ray Charles’ bassist. “It really kind of shaped me growing up,” Burns said, “being part of a huge festival with all these heavy jazz musicians.”

Giant Sand hired him after rehearing a few songs. “And then from that point Joey came into the mess,” Gelb said. “Didn’t know if he was staying or going.” This didn’t matter until a few years later. For now, a group of imaginative musicians had combined their vast ranges.

Gelb wanted his daughter to attend a good school, so he moved the band back to Tucson in 1994. The three musicians rented apartments in old adobe row houses next to each other at 445 S. Convent Avenue, in Tucson’s historic Barrio Viejo neighborhood. No Depression magazine called this “The Giant Sand Compound.” Their houses encircled a shared central courtyard, which the landlord decorated with a sculpture of a saguaro cactus skeleton he made out of metal rods and assorted junk. They drank beer on the steps with neighbors, and the smell of tortillas wafted from open windows. Tucson’s easy artfulness and low cost of living were ideal for working musicians, especially compared to Los Angeles. The city’s multi-culture proved equally important.

Los Angeles began as a Spanish mission and pueblo. Hispanic culture still defines it, and parts of it are true desert. But Tucson’s Spanish colonial character and imposing desert environment were profoundly different than any place Burns had lived. Yards were cactus and dirt. Women sold tamales on the street. Norteño blared from passing cars. Mariachis plucked huge acoustic bass guitars called guitarróns, and he first heard cumbias playing at the tiny Cafe Poca Cosa Mexican restaurant. Burns’ mind filled with ideas. He was creative, ambitious, and a sponge. Naturally, he started absorbing his new surroundings and new friends’ influences. And not unlike the sculptor landlord did with spare parts, he sculpted those sounds into songs.

Burns had released his first solo song, “Do It All the Time,” on a 1993 compilation called Abridged Perversion, by Shrimper records. That was weird white boy indie rock. The mid-’90s were ruled by Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and countless alternative bands that were crossing over from the underground into the mainstream. Instead of the alternative era’s standard four-four strum, the songs Burns started writing in Tucson incorporated gypsy guitar and country, Afro-Peruvian and Portuguesa Fado styles, surf instrumentals and their Eastern scales. He played in minor chords, which created an enchanting, melancholic beauty. And when his friends formed a side-project called the Friends of Dean Martinez, he found his first outlet for testing his unique compositional abilities.

The Friends were a loose collective built around cofounder Bill Elm’s steel guitar. Elm originally modeled it after the mid-century steel guitar band Santo & Johnny. It started as an instrumental cover band, but they and Burns started co-writing originals influenced by jazz and Morricone’s spaghetti western movie soundtracks. Colored with Convertino’s marimba, Gelb’s piano and Burns’ six-string, the band created a sound described as “cowboy lounge” and “desert noir.” Sub Pop released their debut album, The Shadow of Your Smile, in 1995. Pairing vibes with country was unusual but not unheard of. Popular Nashville pianist Floyd Cramer included vibes on his early 1960s Countrypolitan albums like America’s Biggest Selling Pianist. But the Friends’ debut sounded like no other indie band. When I first discovered it in Tucson in 1996, the music captured Tucson’s sleepy, dusty feeling so accurately that their album became the soundtrack of my life that whole year.

“I think Joey really found his voice on the guitar,” Convertino said of this period, “with the Spanish guitar, or classical….he started playing that and it was so soft, I stayed with the brushes, found that I could play a kind of salsa beat, or samba flavored thing that was also kind of like the New Orleans Zydeco beat…..that seemed to open things up for us when we were starting out in the Friends of Dean Martin, and more so when Calexico got going.”

Morricone scores had what Burns called “a lot of playfulness and surprise.” “There were a lot of elements that were distilled when I first moved to Tucson in the early ’90s,” he said. “I found some common threads. Everything from gypsy music, from around the world not just Eastern Europe or the Iberian Peninsula, but finding it in South America or in Cuba, or here in my own backyard in Arizona. Finding these threads and then hearing it in some of the twang elements in Morricone’s score or in Link Ray’s early songs.”

“The Shadow of your Smile by The Friends of Dean Martinez is one of my favorites to this day,” Convertino said. “Really captures a moment there where Joey and I started woodshedding in the studio, coming up with songs together, that record morphed into what truly became Calexico, more than Spoke did in a lot of ways.”

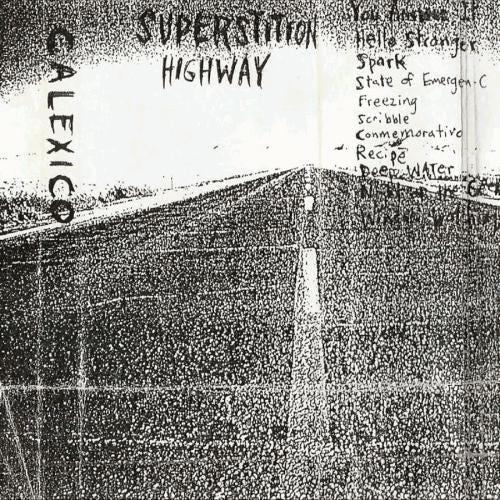

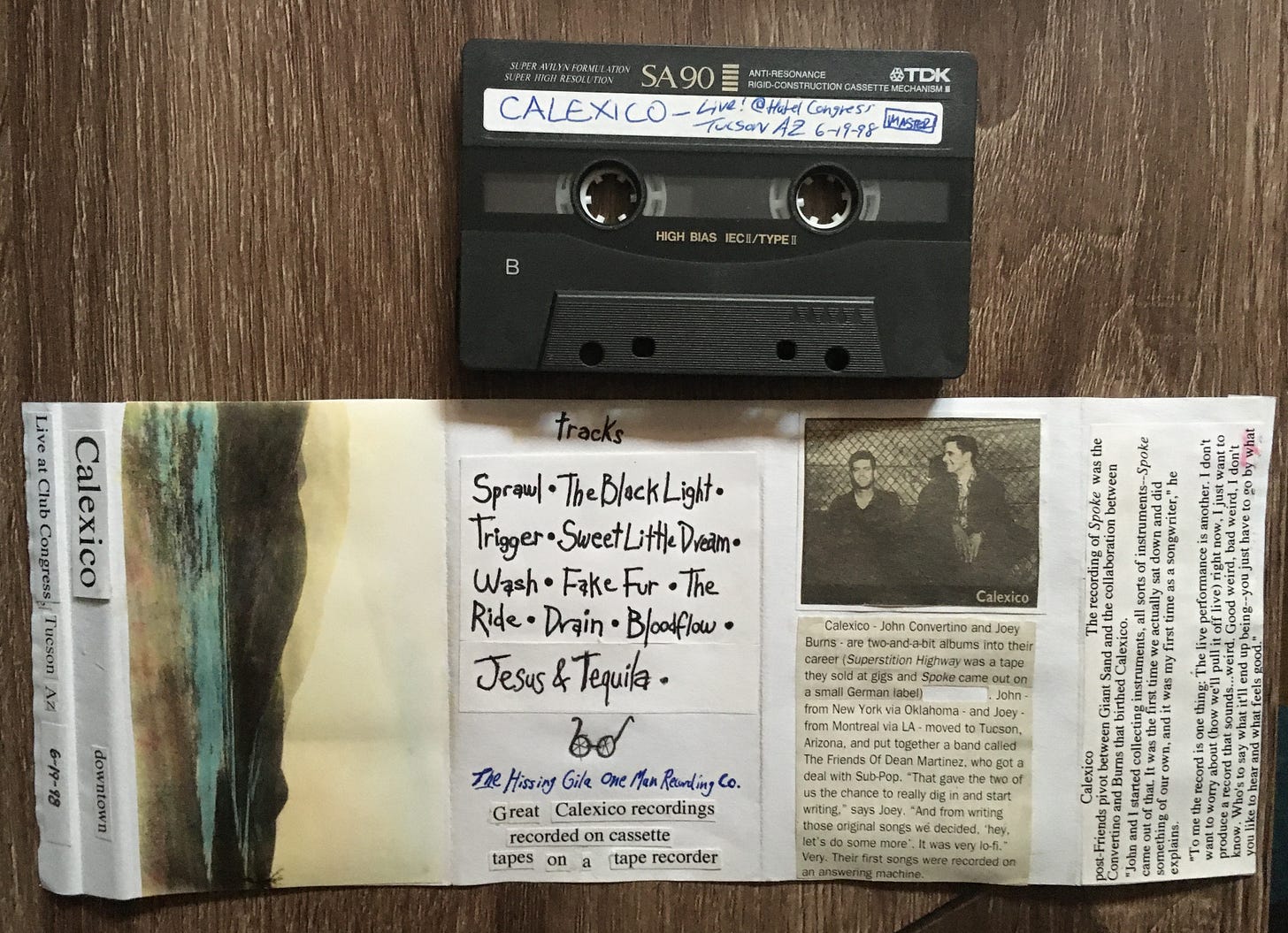

Burns and Convertino kept busy touring the U.S. and Europe as Giant Sand’s rhythm section, and continued writing twangy, Morricone-style songs for the Friends of Dean Martinez’s second album. They also started playing together enough to develop a strong psychic connection. Since 1994, the duo had been casually recording song sketches and melodies on a cheap cassette recorder. They carried the recorder around with them, capturing ambient sounds and ideas as they came—a passing ice cream truck, the automated announcement on a train—and collected what Burns called “a batch of noise and snippets”. They used some of the material as outgoing messages on their answering machines, and they released some on their 1995 tape Superstition Highway. “This first outing was loaded with tape hiss that we tried to sell on the road in Europe with GS,” Burns said. “I bought a cheap boom box there and some tapes and duped a few copies every day to sell that night. Only trouble was, I was either too tired from the travels or the partying or both so that some of the copies wound up being sold as blank cassettes. It took a while before we caught up with technology.”

The Superstition Highway tape was casual and experimental. It contained some good songs and even more promise. The guys turned their instrumental “Chunder” into one of the Friends of Dean Martinez’s best songs. They rerecorded “Spark” for an early 7-inch. They used the ambient piece “Ice Cream Jeep” on the Spoke. Most never got performed, including “Scribble,” the front porch jam “You Are Just It,” and the moody instrumental “Conmemorativo.” Fans searched for the tape and it became a mystical item too few people heard. Even Burns eventually lost his only copy.

The Friends used their Sub Pop money to buy a reel-to-reel eight-track to record rehearsals and song ideas. Everyone passed it around. Between November and December 1995, Burns and Convertino got serious. They borrowed the eight-track to make more professional home recordings of their originals. They used only two microphones. Their apartments’ natural adobe acoustics helped fill out the sound. “The old [adobe] I used to live in had a lot to do with me even buying a house,” Gelb told Tape Op, “with the lack of right angles, because I realize the virtue of the sound in a place like that.” To him, adobe made simple recordings sound warmer, better.

“This house I’m living in now has an amazing sound,” Convertino said in 1999. “It’s got 14-foot ceilings, all stucco inside. It’s just a regular brick house. It has this weird hallway, you know? Rooms with lots of doorways leading into this hallway with this high ceiling. Lots of room for notes, sounds, to go off into a little corner and circulate. You put mics around in different corners.”

Simple and stripped down, the duo co-wrote most of these minimalist songs, which they built around acoustic guitar, vibes and Convertino’s fluid jazz drumming and fine brush-work. Overdubs layered in bass, accordion, cello, violin, mandolin and electric guitar. The stylistic variety made for a refreshingly eclectic mix in the post-Grunge era: instrumental waltzes, a fast surf instrumental, a slow hypnotic xylophone song. In December 1995, TLCs’ “Creep,” and Pearl Jam’s “I Got Id” were radio hits. But Convertino returned to his parents’ music and incorporated it into his song-writing: the jazz, the accordions, and what he called “the old world music” of his Italian immigrant roots. The two originals he contributed were both instrumental waltzes, including a Polish dance song in triple meter called a mazurka.

The more polished vocal numbers like “Wash” and “Sanchez” would end up in their live sets for years. Burns wrote “Wash” soon after moving to Tucson. “I had taken my acoustic guitar to go watch the sunset near Convent & Meyer Avenues, close to where Lalo Guerrero lived in Barrio Viejo,” Burns said. The title takes its name from what people in the Southwest call a wide dry creek bed subject to floods.

The band had Wavelab Studio’s owner Craig Schumacher help edit and polish the songs with ProTools. Before the music became the band’s first record, Spoke, it sat around for a while as they searched for a record company to release it.

After the duo quit playing with the Friends of Dean Martinez in 1996, they focused more attention on Calexico. They also started picking up one-off side-projects, playing as what Schumacher called “the rhythm section du jour” on tours and albums by Barbara Manning, Bill Janovitz, Michael Hurley, and Richard Buckner. When they toured with Manning in ’96 and Bucker in ’97, they also performed opening sets as Calexico.

In the summer of 1997, Burns and Convertino went into their friend, author Bill Carter’s Tucson house on Convent Street to record with local Bluesman Rainer Ptacek. Ptacek seemed to be improving from treatment for brain cancer. He’d just recorded an incredible concert at Tuscon’s Performance Center, and friends were hopeful. He had a lot of friends. After he died in November 1997, these enchanting trio sessions got filed away nearly two decades. They’d already recorded a powerful session on Convent Street in ’93. And in 1997, Burns, Convertino, and Howe Gelb formed a one-off band called Op8 with singer Lisa Germano, and released one haunting, overlooked album titled, Slush. All this additional exposure helped generate more interest in their band.

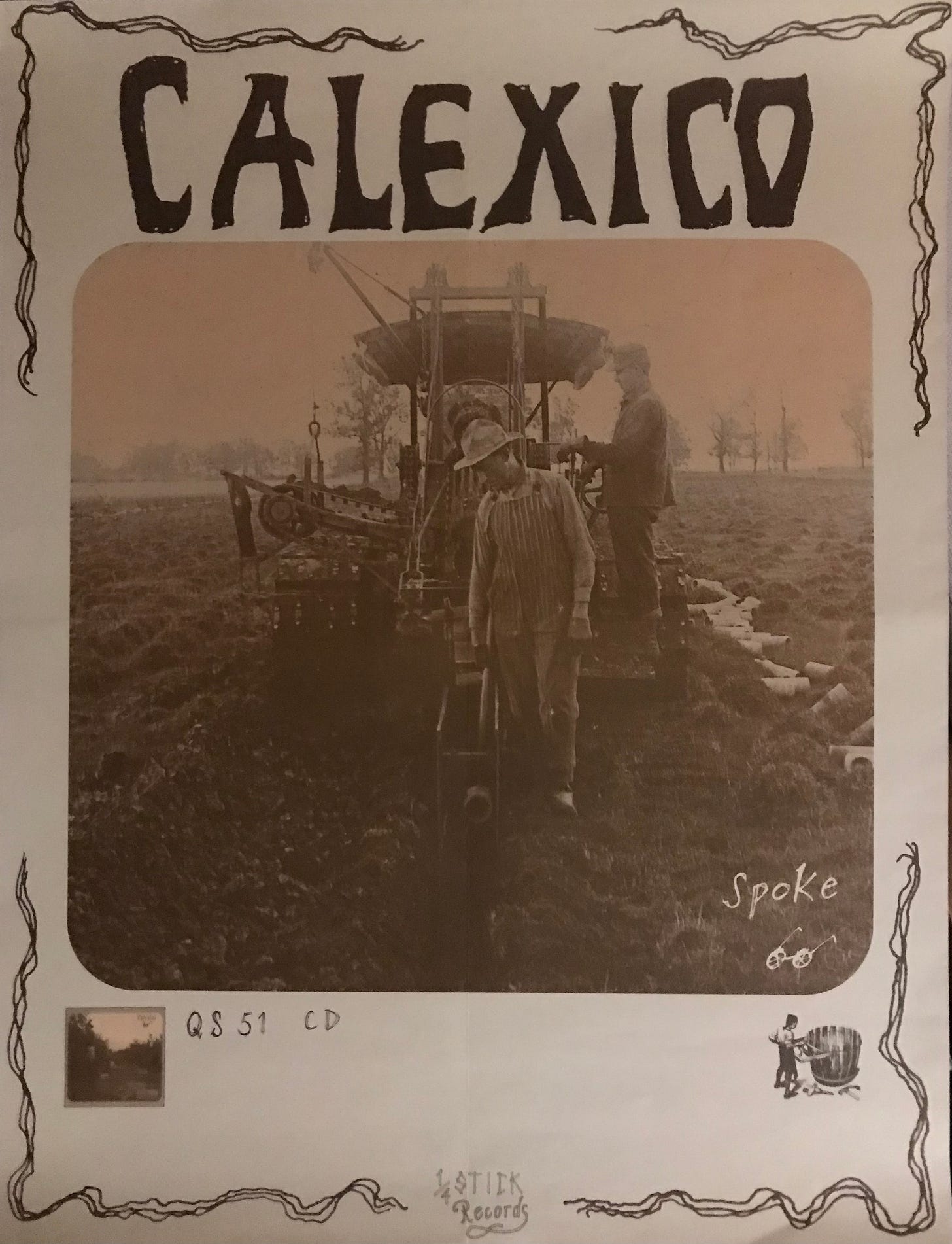

The German Hausmusik label finally released Spoke on vinyl in Europe in 1996 under the band name Spoke. When Chicago’s Quarterstick released it in the US in 1997, it did so under the name Calexico. Another band already called themselves Spoke, so the duo had to find a new name. At the time, their music was incorporating all these Latin American sounds from around Tucson. They frequently drove between Tucson and San Diego to play, and they liked the way the town of Calexico’s name combined two words and two worlds: California and Mexico. “And that’s what we were doing with our music,” Convertino said, “so that stuck.”

People said something special happened musically in Minneapolis after The Replacements came around, just like people said something special had happened in 1970s New York and 1960s London and early ’90s Seattle. In 1997, something was definitely happening in Tucson. As Howe Gelb sang, “There’s something in the water / Besides a moon that don’t know when to quit.”

After I spent all of 1996 listening to the Friends of Dean Martinez’s The Shadow of Your Smile, I went looking for other bands that sounded like them.

When I asked Tucson record store clerks for recommendations, they often said, “Like Shadow of Your Smile? Nothing that comes to mind.” Clerks recommended other Tucson bands. Unfortunately, Sand Rubies sounded too conventional, Luminarios’s Dirt Town had a better name than flavor, and the Giant Sand album that one clerk sold me sounded as close to Friends of Dean Martinez as Coltrane sounded to Ernest Tubb. I was better off putting enchiladas in my ears. I owned enough Morricone and Santo & Johnny to last a lifetime, and none of it shared the Friends’ desert vibe. Then one day in 1997, I asked the clerk at the small Sound Addict record shop down the street from my apartment.

I liked to coast my vintage red and white Schwinn cruiser down the bumpy alley from my apartment and drag my feet to a stop beside the store. A husband and wife team named Tim and Zoe Sanborn owned it. Tim was a large friendly man who wore overalls on the day I visited. It made him sweat. “Like Friends of Dean Martinez?” he said. “Hmmm.” He led me to a rack of CDs along the bright long window, dancing his fingers atop the CDs as we walked, and pulled out Spoke. “Maybe this,” he said. “It’s new. They’re from Tucson.”

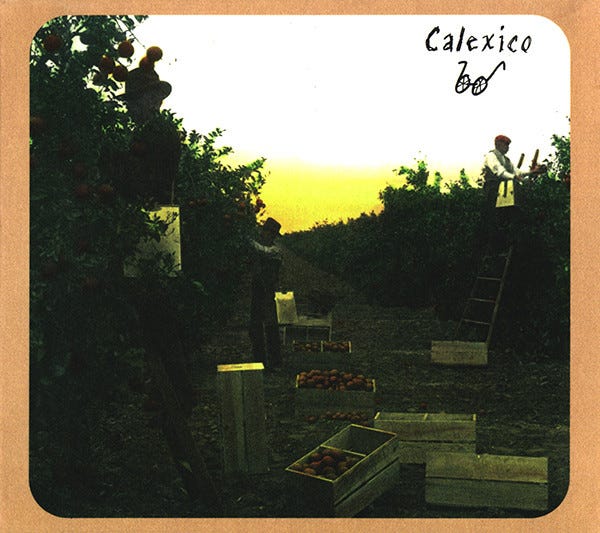

The CD’s cardboard case was the color of dirt, not rich fertile hummus, but a beige thrift store trouser color, slightly lusher than the tan dust that hung over Tucson in summer. The cover featured an old hand-tinted photo of men picking citrus on ladders. It reminded me of the citrus orchards in my friends’ neighborhoods back in Phoenix, and the olive and apricot groves that I drove through in California’s rural San Joaquin Valley. The label said Our Soil, Our Strength. The address: 2509 N. Campbell Tucson, Arizona. The address belonged not to a record company, but to a private shipping service.

When I played the CD at home, the clerk’s cautious “Maybe this” returned to me. No maybe, I thought. This is exactly it. A little country, a little Mexicali, its languid nocturnal folk perfectly matched the tenor of my Tucson life. I couldn’t believe I’d unwittingly lived with this band under my nose for two years. Then again, these musicians played all over town. I just wasn’t looking.

Spoke was essentially a folk album. Unlike The Shadow of Your Smile, the music wasn’t overtly “Southwestern.” It had only occasional steel guitar but less guitar twang. Its strings had more in common with a front porch jam session than a mariachi band. It was mostly acoustic strumming accented by crystalline electric guitar solos and twinkling, reverby overdubs. Combined with the haunting vibraphone and marimba, the effect was beautifully soft and airy, and evocative of worlds beyond geography. This album wasn’t trying to sound regional. It wasn’t trying to calculate anything. Yet somehow the music felt rural. It conjured a historic haunted feeling, like the calm of alfalfa fields under pastel morning skies, like 19th century stagecoach tracks running for miles through dry golden grass—not desert, but deserted. I loved it from the first listen.

The lyrics evoked the arid West more than the music. They spoke of livestock licking on bones, of people staking claims beneath the soil, “Past the border, beyond the hills.” “Step away the night,” Burns sang in “Wash,” “While the whole town’s asleep / Caught between the space where you wanted to be.” Even if he had written those lines in San Diego or Fresno, they spoke of the West’s quiet space, its opportunities for escape. I knew this world. It was the sleepy nocturnal Tucson where vinegaroons climbed your window screens on hot summer nights, the vast scrubland where the starry sky seemed infinite, yet “It feels like someone is watching.”

The way the band separated their songs with those field recordings and fragments also made Spoke eclectic. “I’ve always loved the small pieces of music or snippets,” Burns told Consequence of Sound, “they help connect the dots.”

The drummer’s elegant sensibility stood out, too. His sense of time was more graceful than most indie rock drummers. He rarely played four-four. He played both rhythm and melodies, created mood and played off of what Burns played, producing an unusual back-and-forth between them, a conversation. “He listens to the melody and knows when to play and when to allow room for space,” Burns told one interviewer. “From the first time I met John back in L.A. I was impressed with how both John and Howe Gelb were willing to allow a little chaos into the mix. All of a sudden approaching rock with a jazz sensibility presented itself. John has this ability to switch styles and dynamics so quickly that he winds up not just being a keeper of time but arranging and orchestrating each song from the drum kit.” This drummer had a voice. I’d started listening to mid-century jazz like back then, and I could hear how jazz had directly influenced his fills and use of brushes. Convertino’s thunderous drum rolls were just like Art Blakey’s. Blakey wasn’t something you expected to hear from a folksy desert duo anymore than vibraphone was, but these elements somehow fit into a singular musical whole.

“That’s one of the reasons why we decided to call our band Calexico,” Burns said, “because we’re that kind of strange hybrid — a meeting of worlds that come together under the roof of the Calexico sound.”

Convertino’s playing contained a lot more jazz than Blakey. “1958 does it for me as a drummer,” he wrote on the Bloodshot Records blog. “Looking and listening to drummers from the late-50s till the mid-60s you can hear where musicality and melody began to be played on the set.” Even though he didn’t identify as a jazz drummer, his favorite drummers all played jazz: Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Philly Joe Jones, Shelly Manne, Vernel Fournier, Buddy Rich. As he said, “jazz drumming allows for a freedom drummers don’t often get to have being mostly time keepers in country, rock, and pop. That doesn’t mean we can’t sneak some that deliciousness in our rock country or pop…like the great Mitch Mitchell did with Hendrix, or Stewart Copeland in The Police….or more recently Glenn Kotche with Wilco or the tortoise drummers and the beautiful Jim White with The Dirty Three.”

Jazz often contains a strong Latin or Afro-Cuban influence, which you hear very clearly in samba and bossa nova. Those elements provide drummers a different rhythmic language than rock and roll. Jazz is also driven by what’s called swing, that elusive momentum and energy, often a way of playing behind or around the beat. Even though Spoke didn’t have a Latin character, Convertino’s playing offers proof that jazz’s sense of swing can propel rock ‘n’ roll. “Latin jazz beats or cumbias or Afro-Cuban beats widen the groove,” he said, “a nice contrast to what became of rock ‘n’ roll, which lost the roll and just rocked, which can be great too, but I missed that swing….so I always try to allow for that to happen, that openness, that sweet spot of swing where it feels like you can stop playing and everything will keep going on its own.”

My ears heard all of this without being able to identify much of it. Spoke became the soundtrack to my days throughout 1997, pushing Friends of Dean Martinez out of first place. Spoke played during hiking trips along the mountainous Arizona-Mexico border. It played while driving south of Tucson’s downtown to eat my favorite bean burros at Taquería Guadalajara, played while photographing old mid-century motels and during my constant bike rides around town, even when I had nowhere specific to peddle. It fed my enchantment—with Tucson, with life.

Of course I wanted more, but so far they only had one album and two seven-inches, both of which I immediately bought.

I told that to the clerk at Sound Addict on my next visit. He was playing The Ziggens’ album Ignore Amos. It was a fake country song called “My Paycheck Bounced” followed by a surf instrumental. “It’s just goofy stuff,” he said. “From Long Beach.” Sublime was popular at this time, and he seemed kind of embarrassed of The Ziggens’ affiliation.

I only wish he or anyone had turned me on to their friend, the local Bluesman Rainer Ptacik. He played at some coffee house on Fourth Ave down the street from my house. In 1997, he recorded one of the most stirring live performances I’ve ever heard in 1997, at the church not far from my house. And while I was doing homework or ditching class, he was recording sessions in houses on Convent Street that I now listen to nearly 30 years later. I rode my bike down Convent Street all the time. It’s painful to look back and realize the things you missed. He was so close , and I never knew until he died in 1997. To think that I used to hang out on the bench outside the Chicago Music store downtown, and that Rainer was probably working inside, stringing instruments.

The clerk was glad I liked his Calexico recommendation. “They play in town,” he said. I’d already started looking at the Tucson Weekly listings for shows. It stung to think of all the times I’d already missed them. Fortunately, enough time had passed since they’d released Spoke that I assumed they would release a new album soon, so I kept checking the Weekly for dates. Not long after, I got my chance.

While I obsessively listened to Spoke and did school work in my apartment, the duo was busy recording their follow up at Wavelab Studio down the street—unbeknownst to me.

The Black Light was a concentrated effort. In place of Spoke’s lo-fi production, they developed a fuller, orchestral approach for many songs, enlarging the music in the studio with their eclectic collection of instruments and, in some cases, fusing mariachi with Morricone’s cinematic sound. “On the The Black Light we wanted to have a little better sounding recording,” Burns said. “Yeah, but I wanted to go more away from improvisation and into orchestration and arrangement.”

For songs like “Frontera,” “Gypsy’s Curse,” and “Minas De Cobre,” Burns took a similar song-writing approach that he’d taken on the first Friends’ record, using twangy electric guitar and a lonesome whining steel. He and Convertino still played the main instruments, from accordions to cello, mandolin to marimbas, but they let friends like Howe Gelb, Tasha Bundy, Bridget Keating, Nick Luca, and Neil Harry play other instruments. Burns used storyboards to plot out lyrics to their more narrative songs, the way screenwriters do films. He’d been toying with songs like “Missing” and “The Ride” live for a couple years, though hadn’t committed to the lyrics until recording them in the studio. He adlibbed lyrics to certain songs live, like “The Ride.” Adlibbing was something he’d picked up from Gelb. Unlike Gelb, Burns labored over his lyrics in the studio, often giving them to Convertino for feedback and help making the overt more subtle.

When he set lyrics down for “The Ride,” he drew from Tucson’s unofficial mayor, guitarist Al Perry. A local legend who’d played in numerous Tucson bands since the 1970s, Perry merged surf, country, Blues, and rock ‘n’ roll with his own dry comic sensibility. He paid his rent by doing data entry and working the front desk of Hotel Congress downtown. Everyone knew him. As Club Congress’ booker David Slutes remembered, “Cat Power would walk into the lobby and say, ‘Hi, Al.’” A visibly surly presence in the lobby, Perry was actually a warm generous soul who would share music with anyone passionate enough, and brave enough, to ask him for recommendations.

“So many times I’ve gone to see Al working at the front desk at Congress because I wanted to talk about music and I knew there was a lull in the shift,” Burns said. “I’d go late at night to find out what he was listening to.” Perry takes pride in introducing musicians to other Arizona bands, especially older ones that don’t get enough recognition. Some of Perry’s favorite Arizona musicians include Rex Allen, Chuck Wagon and the Wheels, Black Sun Ensemble, Phantom Limbs, Hacienda Brothers, Duane Eddy, Dusty Chaps, and Calexico.

For what they renamed “The Ride (pt II),” Burns returned the love by writing lyrics that drew from Perry’s “late night graveyard shift” at the old hotel:

Beneath the neon hub of downtown

The local hotel ghosts blow back around

Descend on those drugstore cowboy nights

Cling to the bar, then disappear from sight

As with Spoke, the duo also wanted to create a tapestry by separating the big orchestral songs with simple sketches or snippets. “With The Black Light I decided I wanted to try and do some stuff at home,” Burns said, “so I borrowed a four-track and did some rhythmic stuff. I wanted to break up the songs and the huge amounts of orchestrations with really simple, monotonous things. To put you in the trance state. John came over one day and picked up the bass and I hopped on a pot or a pan or a shaker and recorded a couple of songs like ‘Fake Fur’ and ‘Chach.’”

One of the highlights of those home recordings is the instrumental interlude “Where Water Flows.” “Just vibes, guitar and cello on a four-track at home,” Burns said. “John has been doing that for a while because that’s his roots. There’s a tradition that comes through on each record. It’s got that flavor. For me it’s like the spaghetti in the Spaghetti Western. We have all these different styles. Sometimes I think we could do a whole record of stuff like ‘Where Water Flows.’ I wanted to utilize all these different instruments we’ve been collecting, like marimbas, vibes, mandolin, the accordion. Here where we live it’s called Barrio Viejo. Some of the oldest buildings in Tucson are right here. So you have a lot of old Mexican families here, the music blaring on Sundays. The family coming by, the low-riders crammed with kids. The life down here breathes a completely different kind of breath. At times you can lose yourself. Am I in Mexico or in America?”

Craig Schumacher ran Wavelab from inside an old warehouse at 125 East 7th Avenue. Located right across from the train tracks that marked the northern edge of downtown, Wavelab’s microphones often picked up the sound of passing trains. You can hear the horn blowing during a quiet instrumental section on the song “The Black Light.” You can hear it at the start of “Missing” and in their mariachi epic “Minas De Cobre.” Wavelab eventually moved downtown far from the tracks, but not before inadvertently imprinting Tucson’s atmosphere on this iconic Tucson album.

Convertino liked the results, partly because he liked the sound of the old Wavelab Studio. The big room improved his drums’ warm natural tone. But he liked the sound of their old adobe houses, too. “There are some things about that Spoke record that I like better,” he said. “More open. You hear the air.”

When The Black Light came out, critics described it as “desert rock,” “mariachi garage,” “desert noir,” and “lo-fi Tex-Mex.” They said it sounded like a lonesome highway, a soundtrack to unwritten movies, haunted, “like visiting the ghost-town set of a forgotten Western: Think tumbleweeds and saguaros.” They applauded the duo’s ability to channel the city’s unique personality into a so-called “Tucson sound,” even as they struggled to articulate exactly what that sound was. One Boston journalist called the album “squiggly, multicultural alterna-country.” England’s New Musical Express said it shared “the creepy intimacy of Angelo Badalamenti’s work on Twin Peaks.” As Westword put it, after The Black Light “Calexico became almost uniformly regarded as the sonic ambassador of the mighty Arizona desert,” even though they hadn’t intended to speak for Tucson, let alone the entire state.

The Black Light contained their version of Tucson, what could be called the version of two passionate, naturalized outsiders. Tucson didn’t only sound like a Hollywood Western. The band knew that, but they were experimenting, gathering all they heard and saw into a single artistic statement that combined their influences and interests at that time. “That’s just testament to ‘You write what you see, you play what you feel,’ and that was happening there,” Convertino said. Burns was still unraveling his new home’s cultural DNA, spinning the threads into a new tapestry during what might be called his Western phase, where he spoke musically with the established language of the cinematic American West before his vision evolved. Anyway, only a few songs sounded like Morricone’s. The Black Light was as eclectic as Spoke, just more hi-fi. The month it came out, the band knew who they were musically. Victor Gastelum’s cover art gave them a visual identity that kept for subsequent albums. Burns had become a more confident frontman, and the duo settled on their name.

Excitement built quickly around The Black Light. By May 1998, college radio stations played its songs. People outside of Tucson’s musical underground had started hearing about Calexico, and Tucson was excited. “If ever a record was made expressly to give purpose to the ‘repeat’ function of your CD player,” Tucson Weekly wrote in April, “The Black Light is it.” Phoenix always treated Tucson as a second class citizen. As an underdog, Tucson loved a hometown success story, and the local Tucson Weekly championed Calexico the way it championed underground Tucson musicians Giant Sand, Rainer Ptacek, and Al Perry.

“My money is on the table,” Tucson Weekly said in 1998. “Calexico’s going to be famous. And it couldn’t happen to nicer guys.”

To support their album, they embarked on a six-week national tour, opening for the Australian instrumental band The Dirty Three. It was Calexico’s first U.S. tour under their own name. Little did they know, it would be their last tour as a duo.

Burns and Convertino had long wanted to grow their band. “It would be nice to expand the Calexico lineup and get a fuller sound,” Burns told No Depression in 1997, but “a two-piece band is really good for songs, I think.” Touring as a full band was also expensive. As an indie band on indie labels, they didn’t have the budget, so they didn’t let their live format limit what they did in-studio. “Because, in our hearts we’re thinking, ‘Let’s just overdub some parts here,” Burns said. “Let’s see what we can pile on here to kind of make this more an orchestral or ensemble kind of recording.’ We’ve always been fans of, not necessarily big bands, but more ensemble.” Fortunately, fans made live recordings that captured the duo before the band retired the format.

Like Calexico, The Dirty Three had a unique sound. They were a trio, slow and melancholic, with guitar and violin taking the place of a vocalist. That March they’d released what would become their most beloved album, Ocean Songs. Convertino and Dirty Three drummer Jim White found they had a lot in common, and they bonded over their shared free-form technique.

Starting at Chicago’s Lounge Ax, the tour wound through Detroit, Columbus, Providence, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. They played Washington DC’s legendary Black Cat, Louisville’s tiny Mercury Paw, and a place called Sudsy Malone’s in Cincinnati whose beery name fit the headliners’ lifestyle.

After playing Minneapolis’s 400 Bar in early June, the tour headed up the West Coast. One fan, Erik Johnson, recorded two of the four West Coast shows on his digital audio tape recorder, or DAT.

Raised on underground music in 1970s San Francisco, Johnson moved to Seattle and saw soon-to-be legendary bands like Nirvana and Mudhoney play small Seattle clubs like the Central Tavern before Grunge became a buzzword. He moved to Portland in 1989 and continued seeing so many shows that he decided to invest in a DAT to record them. In 1996, his first DAT deck, microphones, and chords cost over $1200, but he quickly got on such good terms with the sound guys at local Portland clubs like Berbati’s Pan that they let him tape nearly any show there, and he got his money’s worth. He taped early Elliott Smith and Wilco shows. He taped The Melvins, Yo La Tango, Uncle Tupelo, and Mark Lanegan. His 1999 soundboard recording of Tom Waits playing Eugene, Oregon sounded so good that bootleggers pressed it onto CDs to sell without Johnson’s permission. That broke the taper code and really pissed him off. “I don’t make money off of bands,” he told me. “I just like to listen to them.” The thievery didn’t slow him down.

Already a fan of Giant Sand, Johnson saw both bands played at the previous year’s SXSW. Giant Sand had long enjoyed a devoted cadre of fans who recorded and traded tapes of their shows, especially in Europe. In 1997, a tape trader faxed Gelb a list of bootleg recordings he’d assembled. “Really incredible, the amount there, and where they’re from, live stuff, studio sessions,” Gelb told Tucson Weekly. “People are trading tapes of us like the Grateful Dead.” Portable recording technology had improved in the 1990s, making it easier for fans to make high-quality digital live recordings on small units that could evade security. The popular CD format made it easier for illicit operations to press and sell those recordings as bootlegs, especially in Italy and Luxembourg, where legal loopholes existed. (It turned out that the same solo Howe Gelb show I filmed at Portland’s Berbati’s Pan, Erik recorded through the board.) Naturally, fans would do the same for Calexico, too.

Another fan, Mike Brewer, built his own Giant Sand website, call sa-wa-ro, to post news and tour info. Johnson loved Calexico’s SXSW set so much that when he found the band’s mailing address on Brewer’s website, he wrote Calexico a fan letter and ordered Spoke through the mail. “My memory is a little foggy, but I am pretty sure Joey wrote me back,” Johnson told me, “and we started some correspondence back and forth.” He and the band traded a few handwritten letters.

Johnson worked as a high school teacher, but he spent most of his free time recording and trading shows with other fans on early sites like the DATheads mailing list. He was 32. In 1997, after SXSW, Tasha Bundy emailed Johnson to ask if John and Joey could stay at his Portland apartment after their show. They were touring as Richard Buckner’s rhythm section. Unfortunately, that tour fell through. In 1998, Bundy emailed Johnson with the same request. Of course, Johnson said. So he drove up from Portland for the Calexico show at Seattle’s Showbox theater, and the band let him plug his DAT into their equipment. This got him a professional-sounding recording, rather than the often tinny or bassy recordings bootleggers get from holding ambient microphones somewhere in the audience. The band only asked for a copy in return.

The Showbox wasn’t very full, but Mark Arm from Seattle’s legendary Mudhoney was there. That seemed fitting, since Arm’s band and Sub Pop Records helped inadvertently change Seattle in the same way Calexico would soon change Tucson: broadcasting its charms to the world, making it cool, known for music, and later, more energized and expensive. Technical problems plagued the Seattle show: bad connection in the guitar monitor and pedals, which sounds, in Burns’ words, like “sand in the monitors.” Small clubs don’t always bring out a band’s best sound the way old theaters do. Their instruments would sound richer, more robust and less tinny, in certain rooms than others. But in terms of fidelity, Johnson’s crystal clear digital recording is almost as lush as any officially released live album. Just as importantly, it captures a band alive and inspired, unafraid of making mistakes on stage when jamming liberated them to make discoveries.

They played “Spokes” and “Sanchez” from Spoke. They played covers of Granddaddy’s “Taster” and covered two songs from Tucson’s legendary Blues guitarist, their friend Rainer Ptacek, who had recently succumbed to brain cancer: “Opening Aunt Dora’s Box in 6/8” and “Sea of Heartbreak.” That night they only played “Fake Fir,” “Trigger,” and “The Black Light” off their new record. Without a trumpet player, violinist, or a melodica, they couldn’t play faithful renditions of new songs like “Minas De Cobre,” “Stray,” or “Gypsy’s Curse.” They were in a transitional phase: a duo promoting an album with a big sound, but still a two-piece limited to their simpler repertoire. Still, this transition wasn’t a creative limitation. It forced them to play harder and more imaginatively, to do more with less. Where Spoke’s eight-track versions of “Wash” and “Sanchez” had overdubbed instruments, on stage they still managed to create a full sound with only guitar, drums, prerecorded loops, and effects pedals. That minimalism really showed off their unique songwriting and adventurous spirits. The Seattle show left such an impression on Johnson that he taped their sold-out show at Portland’s infamous Satyricon club days later.

“The Portland show at the Satyricon was an all timer,” Johnson told me. “Not sure if you are familiar the old venue, but it had no air conditioning and it was an incredibly hot night inside. It was packed to the gills of people yearning to see The Dirty Three, but John and Joey slayed as a duo.” They opened with an instrumental track that used tape loops and haunting staccato guitar to set an eerie mood, then dove into charged versions of “Trigger” and “The Black Light.” They covered The Clean’s song “The Blue” from the legendary New Zealand band’s 1990 full-length debut Vehicle. They played old songs “Drape” and “Return of the Manta Ray,” which they only released on small circulation 7-inch records. The crowd loved them. You can hear it in their applause. The band attempted a version of “Stray” without the trumpet. It highlighted Burns’ beautiful guitar picking and sense of melody, but it’s the addition of brass that made this dynamic song essential to future performances. They closed with a searing rendition of the song “Slag.”

On Spoke, “Slag” is an innocuous tune with a heavy bassy bottom end and a loose, jangly acoustic guitar line. Here, Burns sped it up and played electric, using a slide to turn it into an upbeat Blues tune that would have pleased the late Rainer Ptacek. Years later, after the band got pigeonholed as a mariachi noir band, an electric Blues would stand out as an anomaly. But as a two piece, this version displayed Burns’ ability to play in many genres when he chose to, and showed the band’s range, and the range of his influences. Their first two records are nothing but eclectic illustrations of the members’ diverse interests. “Slag” took the breath out of the room and ended the set on a high note. Johnson said, “That tour they did made huge fans out of many people.”

The Satyricon recording sounded much better than the Showbox. No equipment malfunctioned. Johnson’s DAT captured a cleaner sound, and that old sweaty punk club somehow brought out the best of the band’s fidelity. Maybe its punk spirit also encouraged a more aggressive, daring performance. Plugged directly into their equipment, Johnson got a clear document of a powerful band in peak form, experimenting with their approach, still exploring each song’s sonic possibilities, excited by the novelty of their music and their intuitive relationship as collaborators.

Johnson’s recordings highlight the band’s improvisational approach, which they learned from Gelb and from mid-century jazz. On this tour, they played a different set each night, and they often played the same song different ways each night. They stretched out here, tried a new intro there, sometimes add a second guitar solo if the mood struck. In Seattle, they sped up the gentle, lonesome campfire song “Spokes” into a fast rock ‘n’ roll tune. In Tucson, they mixed Rainer’s “Waves of Sorrow” into the beginning of “Wash.” In Detroit, they stretched out on “Glimpse,” starting it with a lush instrumental intro that gave this dusty folk song the ethereal pop sound of The Clean. Thanks to the nature of improvisation, some versions turned out better than others. The best are inspired, one-of-a-kind takes they couldn’t replicate in a studio if they tried, what Howe Gelb once called “happy accidents.”

Johnson’s recordings capture Convertino’s lyrical, nuanced drumming, a style Gelb called “poetic.” The simpler format gave Convertino room to play his own melodies like any other soloist, and he played them differently each night. He changes time for a few measures during a song. He taps the open high-hat at random intervals, letting the rattling metal add a layer of texture. He adds minute accents, like hitting a single rim shot on the snare hard enough to echo through the room, or hitting the tip of his stick against the symbol once—all small additions so fleeting most listeners would miss them. At one point in “The Blue,” he hits the crash cymbal with increasing frequency, so the sound rises in volume to a crescendo before he does a drum roll into the chorus. Such devotion to detail, just for a live performance.

Just as Gelb and Convertino had as a duo, Burns and Convertino forged a strong psychic connection. On these recordings, they played in sync. When Burns went up in volume, fortissimo, Convertino went with him. When Convertino dropped down low, pianissimo, Burns went, too. Convertino pushed Burns instead of simply following Burns. Because they were improvising, Convertino couldn’t always anticipate where the guitarist was going either: Would he go into the chorus? Would he adlib an instrumental bridge? Did he miss his mark and need to vamp a few measures before starting to sing? Unlike Convertino’s experience with Gelb on The Love Songs record, on Johnson’s recordings, he didn’t go into a chorus that wasn’t there. He made no mistakes, because he embraced them.

“The most important thing is leaving yourself open to letting things smash and break,” Burns said, “for those moments when you just kind of let things happen and see where the ghost wants to go.”

The minimalist setup also highlights Burns’ skill on guitar. He has a distinct voice, unique phrasings, and he’s an inventive, unheralded soloist. His solos in “Trigger” vary wildly night after night; some rely on slide, some rely on picking, some sound like a gypsy version of The Ventures. With the switch of an effects pedal, he would fill the venue with ethereal echoes that grew louder as they went into a verse, letting the noise pulse through the room. Burns’ adlibbed lyrics to “Fake Fur” are often goofy—and probably embarrassing to the more sophisticated Burns now—but something about the eerie sound of his slide guitar captures a deep part of southern Arizona’s personality. It sounds like a centipede looks scampering across the desert floor, the way nights feel when javelina and coatimundi prowl the limbs of old oaks in the mountains along the border. At the San Francisco and Seattle shows’ instrumental introductions, Burns plays these staccato notes, vigorously hitting a single string over and over, that chill me to the bone, especially when he plays two strings at once to create a haunting chorus. It sounds like voices crying from the other side. These aren’t accents. They’re the song’s frontline, so they define the band’s old sound more than mariachi trumpets or lap steel.

As a duo, there was no pretense. They weren’t trying to sound Southwestern. They were just writing good songs. As a duo, the minor keys Burns played evoked something more powerful and haunting than the orchestration ever could. I love the orchestration, but the Morricone approach evoked visions of a place as seen through a familiar Hollywood lens. Even though no indie bands were doing that, it eventually grew to sound less original than this first iteration.

Instead of the usual tour van, the band rented a big new Cadillac in Seattle, and they traveled light enough to packed all their equipment in the Cadillac’s trunk.

While The Dirty Three played Satyricon, Johnson and Calexico hung out outside the club talking. They planned to crash at his place, drink some coffee in the morning then head out. Instead, Burns got a call during the show: a San Francisco radio station wanted them to play live on the radio the following day. Convertino was exhausted, but he knew a Bay Area broadcast was good publicity for their budding band, so the two thanked Johnson for his offer, loaded their Cadillac, and took turns steering it down Interstate 5 all night to San Francisco, where they broadcast their set, then played the Great American Musical Hall that night.

Johnson couldn’t make that show, so he convinced his friend and fellow taper Jason Sherrett to record it. Sherrett’s recording sounds crisp and robust, with a full range from high to low, but as far as performance, it’s the weakest of the three sets. The band isn’t as consistently dynamic, and Burns seems less sure of himself, hesitant, and gets lost in some sections of songs and certain lyrics. Maybe he’s tired. But when they were on during songs like “Sanchez” and “Opening Aunt Dora’s Box in 6/8,” they were really on. Once again, their willingness to play different sets each night, and to let fans record their performances, speaks highly of the adventurous duo’s dedication to experimentation when it pushed them to deliver the best performances. Burns said, “I am looking for ways to make each and every show as unique and special as can be.” They would keep experimenting with sounds and arrangements for the duration of their careers, over the course of over nine albums and various collaborations. Even when they cover familiar ground, they’ve never stopped trying to evolve. It all started here.

Each of these three 1998 recordings contain stand-out songs, but on the whole, song-for-song, Johnson’s Portland show is the best, with the cleanest sound and most intense performance. Although the band generously allowed Johnson to share the Satyricon show online for other fans, interestingly, none of the band’s six official live albums come from this duo era.

Years later, in 2001, the band hired their own archivist, Jim Blackwood, to make professional, multi-track, soundboard concert recordings in cities like Portland, Amsterdam, and Denver. But at this early stage, with no such infrastructure, fans inadvertently did that job for them. Or not. It was pure luck. So many shows went undocumented. Others got taped on poor-sounding audience recordings, like the show at Detroit’s Magic Stick. This set shows the band in peak form. Had they taped it professionally through the soundboard, it would have made one of their best live recordings. Burns sounds confident. He tears through blazing surf-guitar solos. Instead of wrapping up, he ripped through a second solo in “Trigger” as the mood struck him. Surely other shows featured equally inspired moments. The West Coast shows are unique because they got captured with such high fidelity. Had Erik Johnson not taken a personal interest in his beloved band and not had that documentary impulse, we’d have a poorer document of this part of Calexico’s life. If he didn’t have a DAT and the documentary impulse, we’d have just another bad bootleg recording where you can hear beer bottles clinking on tables and people talking next to the microphone.

Although Johnson didn’t tape their show at Vancouver, British Columbia’s Starfish Room, one fan named Richard Fogar took photos. He’d seen Burns and Convertino play in Giant Sand in Edmonton six years earlier. He was 14 at the time but snuck in by working the opening band’s merchandise table, and he got to hang out with Burns there, too. Now 20 years old, Richard caught Calexico play Vancouver’s Zulu Records in the afternoon, then he got to the Starfish Room early to chat with the duo. The band played for 90 minutes before the doors opened, performing a loose pre-show set during their soundcheck for a few early birds and the club’s few employees. “Seriously one of my very favorite music moments ever,” Fogar remembered years later. “This was a very special day.” Grateful for this fan’s efforts, and aware how important his and Johnson’s documents were, the band later used some of Fogar’s photos in the liner notes of their 2000 tour-CD Travelall.

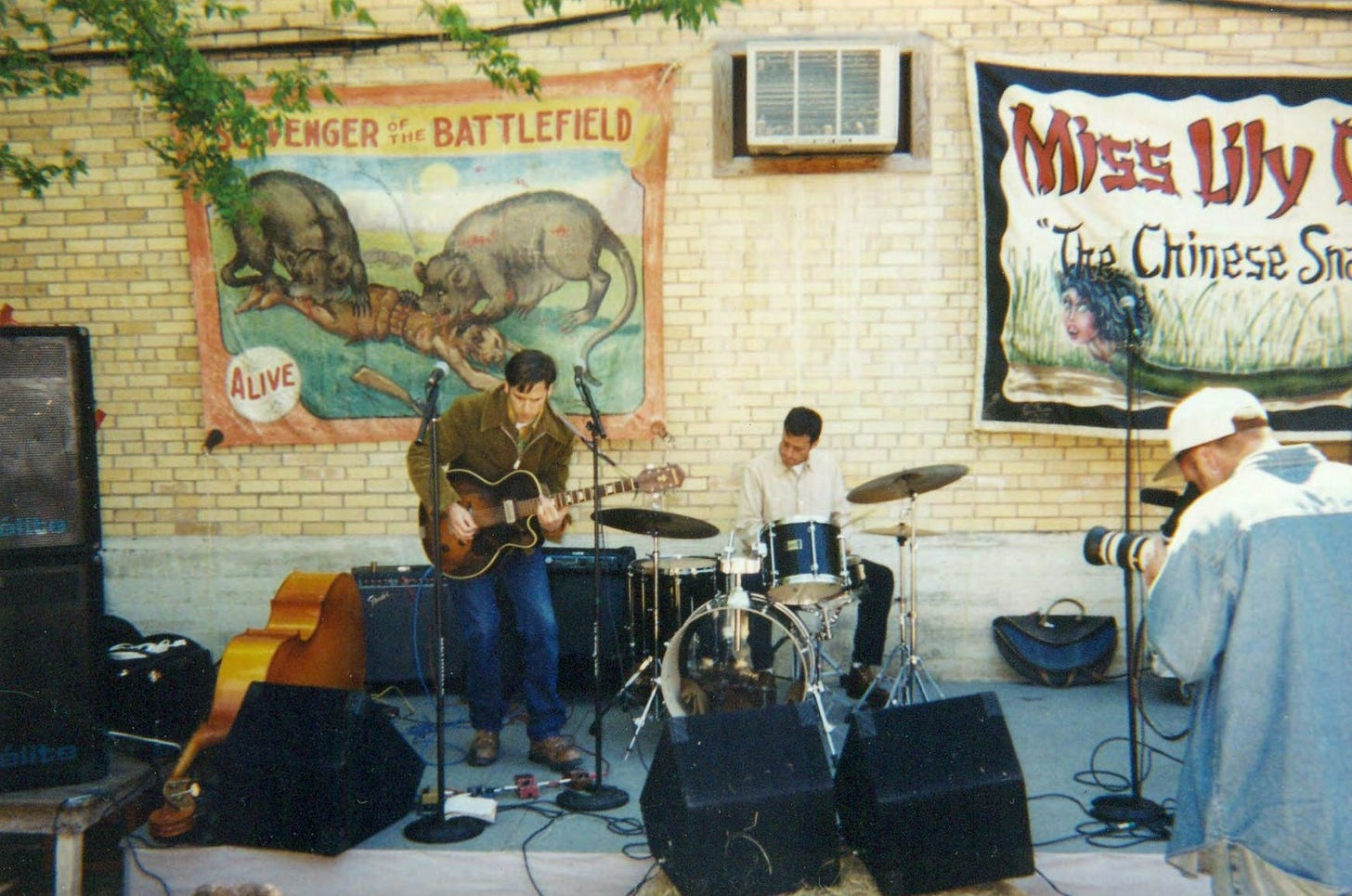

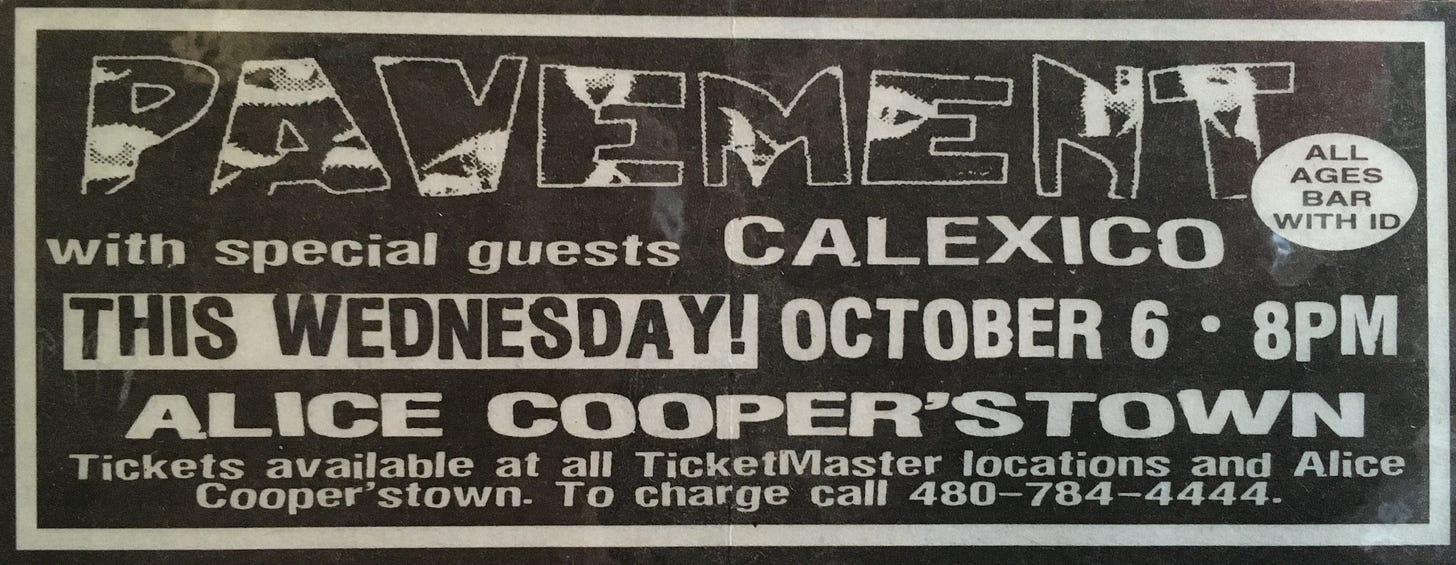

After playing San Francisco, the tour returned to Calexico’s native Southwest for more shows. Back in Tucson, a month after The Black Light came out, the band played the town’s best underground venue, Club Congress. My chance to hear them play had finally come. Their performance was phenomenal.

The band opened with a new slow instrumental called “Sprawl.” Gradually getting the beer-drinking audience’s attention throughout the bar, and setting the mood, “Sprawl” moved right into the song “The Black Light.” After that they tore through “Trigger,” “Return of the Manta Ray,” “Fake Fir,” “The Ride,” “Drape,” “Bloodflow,” and gave a nod to their deceased friend Rainer, playing a snippet of his song “Waves of Sorrow” at the beginning of “Wash.” I was thrilled. I’d wanted to hear these live since I found Spoke. Unfortunately, the Panasonic handheld cassette recorder that I captured it on didn’t do the show justice.

My dad had given me his bulky recorder in 1991, and even though security was stiff in the ’90s, I recorded many shows: Nirvana, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Wonder Stuff, The Bomboras, Mr. Bungle, and Fishbone. Because I owned tons of unofficial live recordings, I appreciated their importance, and I believed I was performing a similar cultural service by making my own. Too bad my bootlegs mostly sounded bad; every song in Nirvana’s 1991 set except “Polly” sounded like someone had put the tape inside a washing machine. My best friend JR worked at a copy shop, so we made color covers for The Wonder Stuff and Nirvana bootlegs there, despite complaints from people we sold them to. “This sounds like shit,” our customers said. “Yes,” we said, “it’s a bootleg.” Thankfully Calexico’s set sounded pretty good. The clunky machine’s small built-in microphone made the music dense and bassy, with insufficient definition, but the small club space gave it sufficient fidelity that you could listen to it.

I did what I always did and immediately created a cover for my cassette. When I made people copies, I would copy this cover.

In hindsight, the other bands on the bill at Club Congress offered unexpected insight into the two poles the band was moving between stylistically. The Dirty Three were widely categorized as a low-fi instrumental band; Spoke put Calexico in the same low-fi category. The local brass band Crawdaddy-O opened. They consisted of a loud lineup of two trumpets, a saxophone and a tuba, and their sound provided a glimpse of the brassy direction Calexico would soon take, starting with its next fall European tour.

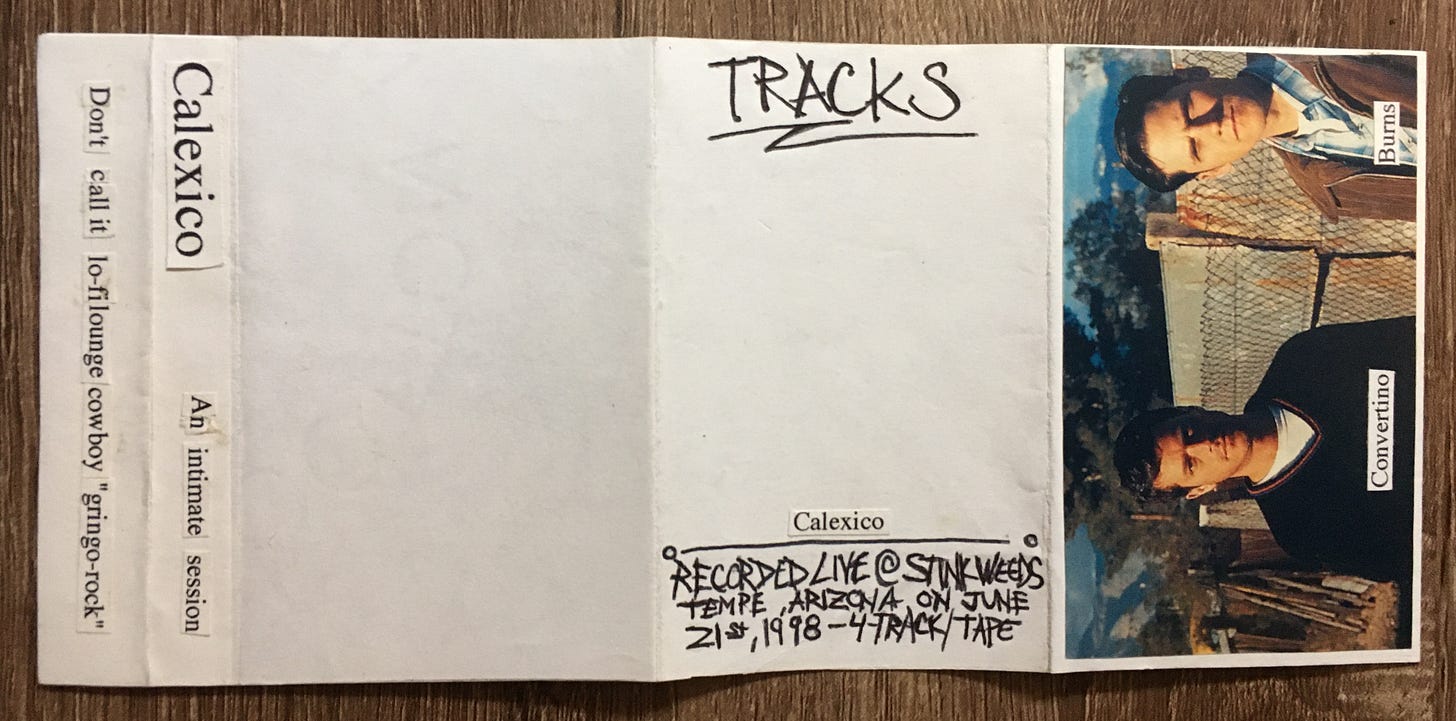

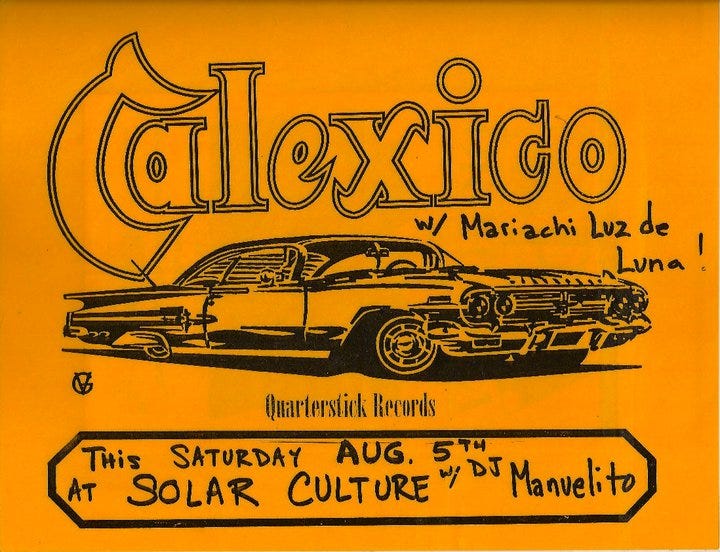

After Tucson, the bands played the Dingo Bar in Albuquerque, then headed west to do an in-store performance at Stinkweeds Records in Tempe, Arizona. About 12 people attended. I’d been shopping at Stinkweeds since high school, so my girlfriend Kari and I drove up from Tucson to hear it.

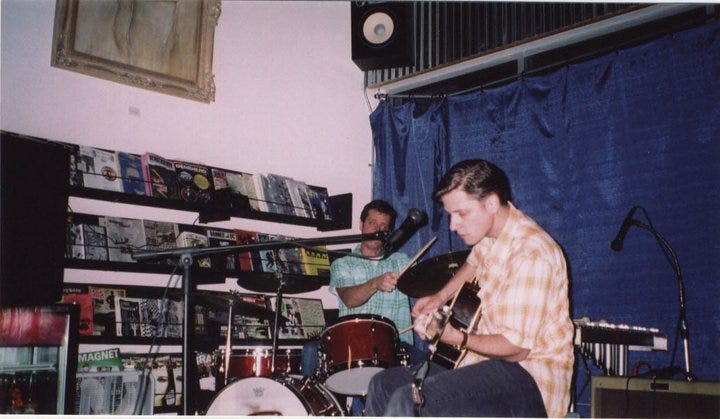

The duo set up in the corner of the record store, atop a low wooden riser next to the magazine rack. Behind them, a blue tarp hung over the store’s front window, blocking the audience’s view of the ugly parking lot outside and keeping passersby from seeing in without coming in. The musicians both wore big baggy ’90s style pants. Burns sat on a blue milk crate in front of a single vintage amp. A selection of effects pedals lay at his feet. Convertino played a sparkly red vintage set, with a small vibraphone standing beside the high-hat. His bass drum featured a Victor Gastelum image of a low-rider, similar to their album cover. Kari and I sat on the floor at the base of the tiny stage. We pressed our feet against the wooden platform below Burns and rested our backs against the case of 7-inch records. Kimber the owner leaned against the front counter beside the cash register and watched. Next door, a health food restaurant served plates of chicken pita and humus. Burns almost forgot about the gig. “Called up Charlie a couple weeks ago,” he told the audience, “said, ‘Charlie, we need to get a show in Tempe.’ Charley said, ‘Joey, you already have a show in Tempe.’ I said, ‘What? No one told me about this show in Tempe at Stinkweeds! Stink-what?’” They opened with Rainer Ptacek’s “Opening Pandora’s Box in 6/8” and “Long Way to the Top of the World.” Unlike the Tucson gig, Burns added a trippy echo to his voice and to Convertino’s vibes, and the echoes filled the tiny store.

Convertino is one of the most original drummers in rock music. It was a treat to watch how he played so closely. He played with his whole body, leaning sideways on his stool between rolls, arching his back in a V when he tapped the ride cymbal for a few measures. He’d shake a maraca with one hand while drumming with the other, then lightly tap his cymbal with the maraca before returning it to the bag that hung from his snare. Chewing on his bottom lip and swaying his head with his eyes closed, his brushes made figure eights on the snare. His foot tapped the high-hat in a waltz a few times. For accents, he’d flip his right brush around in his hand and tap the hard handle against the cymbals’ edges, making a bright clanging sound, all without looking. Then he’d peek to watch Burns for subtle clues about his next move. He constantly dropped his sticks in his bag and pulled out those brushes, trading them back and forth, just like his days with Gelb. His head often hung down in concentration, feeling the melody. His face grew so stoic he even looked bored, but he was clearly having fun. I snapped three photos. None of them captured the show’s energy. They played the obscure “Return of the Manta Ray,” which came out on an obscure comp. They played “Sanchez” and “Windjammer” like it was their last day on earth and blew everyone away. It was the last show on their U.S. shows supporting The Black Light. Besides occasional radio spots and special gigs, it turned out to be one of the last times Calexico played as a duo.

A local fan recorded the performance on his TASCAM four-track deck. He was a musician who regularly shopped at Stinkweeds, and he claimed to have recorded Friends of Dean Martinez playing in front of Hotel Congress a few years earlier, on that same TASCAM. He once gave the band a can of pre-ground coffee as thanks, Burns told me with a shrug. After the set, the fan promised me a copy. “No problem,” he said and wrote his number on the back of a flyer. I designed what I’d planned to be the cover of this live tape, but for weeks, the dude never returned my calls, so my draft cassette cover ended up in a box, unfinished, and I didn’t get to hear the recording.

Months past, then a year. As I let go of hope of ever hearing that in-store recording, the band moved on, too. My Club Congress recordings’ imperfect fidelity didn’t stop me from compulsively listening to it for years. That tape was my only way to hear them play as a two-piece. Like the life Niko Case sang about clinging to tightly, I clang tightly to my tape.

Eight months after The Black Light came out, two regular Tucson Weekly contributors described the album in the paper’s round up of best albums of the year. “Perhaps no other Tucson band represents the sound of what it’s like to live in the Old Pueblo better than Joey Burns and John Convertino,” wrote Stephen Seigel. “We should all be proud of these local boys for bringing the sound of our fair city to the rest of the world.” And Fred Mills said: “Chronicling ‘the Tucson sound’ is a nigh-impossible task, but these homeboys nailed it with their cantina rattle, noirish hum and dark moon twang, earning international kudos in the process.” The message quickly reached the rest of the world. In a 1999 interview, the Australian band the Go-Betweens told Tape Op, “With records it’s really like casting to me, the songs start to get a feel. I want to talk about form. I can imagine going down to Tucson, there’s a feel in that Calexico album and it’s just amazing. You just get into it.”

“The number-one question we get asked is, ‘What role does geography play in your music?’” Burns told one interviewer. “Tucson does fuel a lot of inspiration—there’s a spaciousness here you feel when you wander out into it that I think reflects in our music. That idea of space is very tangible in what we do. The feeling of slowness, of self-awareness. But, really, everything comes down to your own interpretation and how you adapt to and incorporate the place that surrounds you into your art or your life. We are definitely not out to create the ‘Tucson sound.’”

Asked how their music became “so evocative of place, real or imagined,” Burns told another interviewer that this geographic association starts with the instruments. “When you hear violins and trumpet together or a nylon string guitar in waltz time, a landscape comes with it,” Burns said. “But how the idea and story of a place is adapted is also a big theme down here in Tucson and in the Southwest in general. We’re close to another country and people tend to pass through here a lot, so apparitions float around down here.”