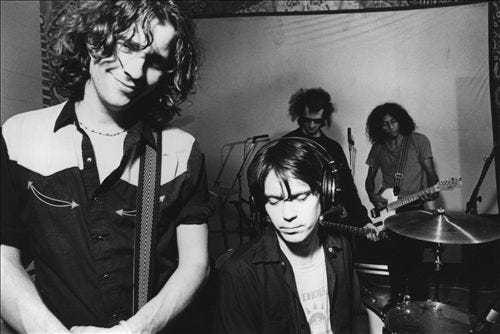

“It just seems like The Flaming Lips are sort of this thing that’s, like, I don’t know how seriously you should take us as, like, something to base your life off of.” —Wayne Coyne, 1988

“On a smaller scale, I think the punk rock thing was similar to the hippie movement.” —Cris Kirkwood, The Meat Puppets

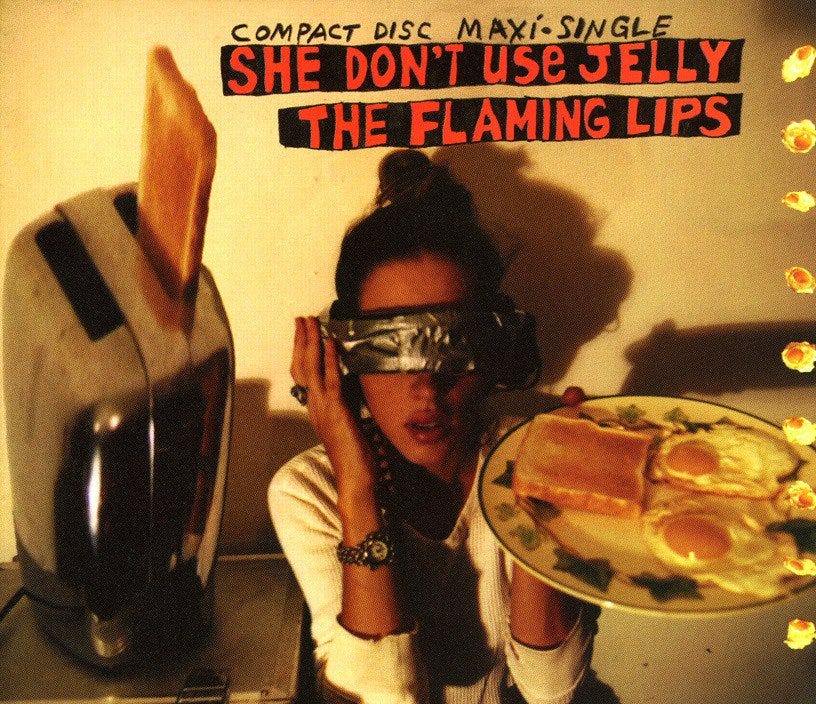

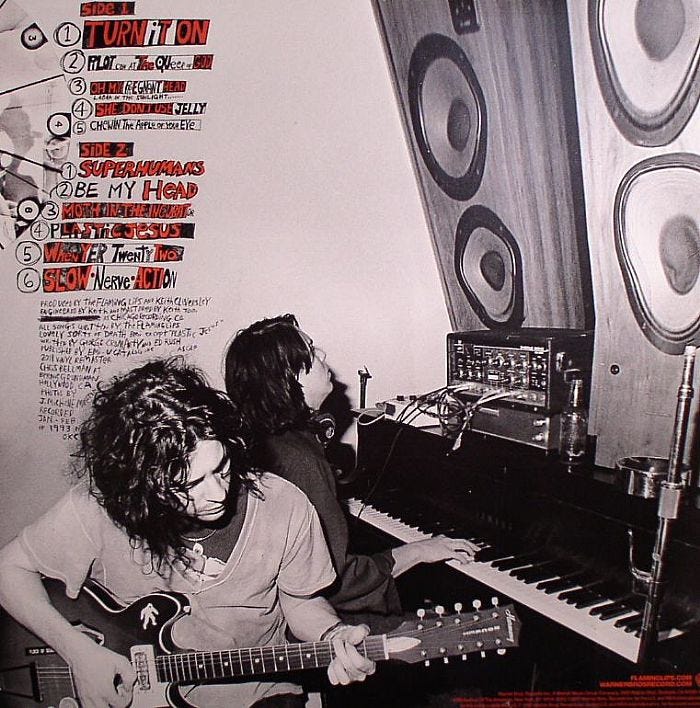

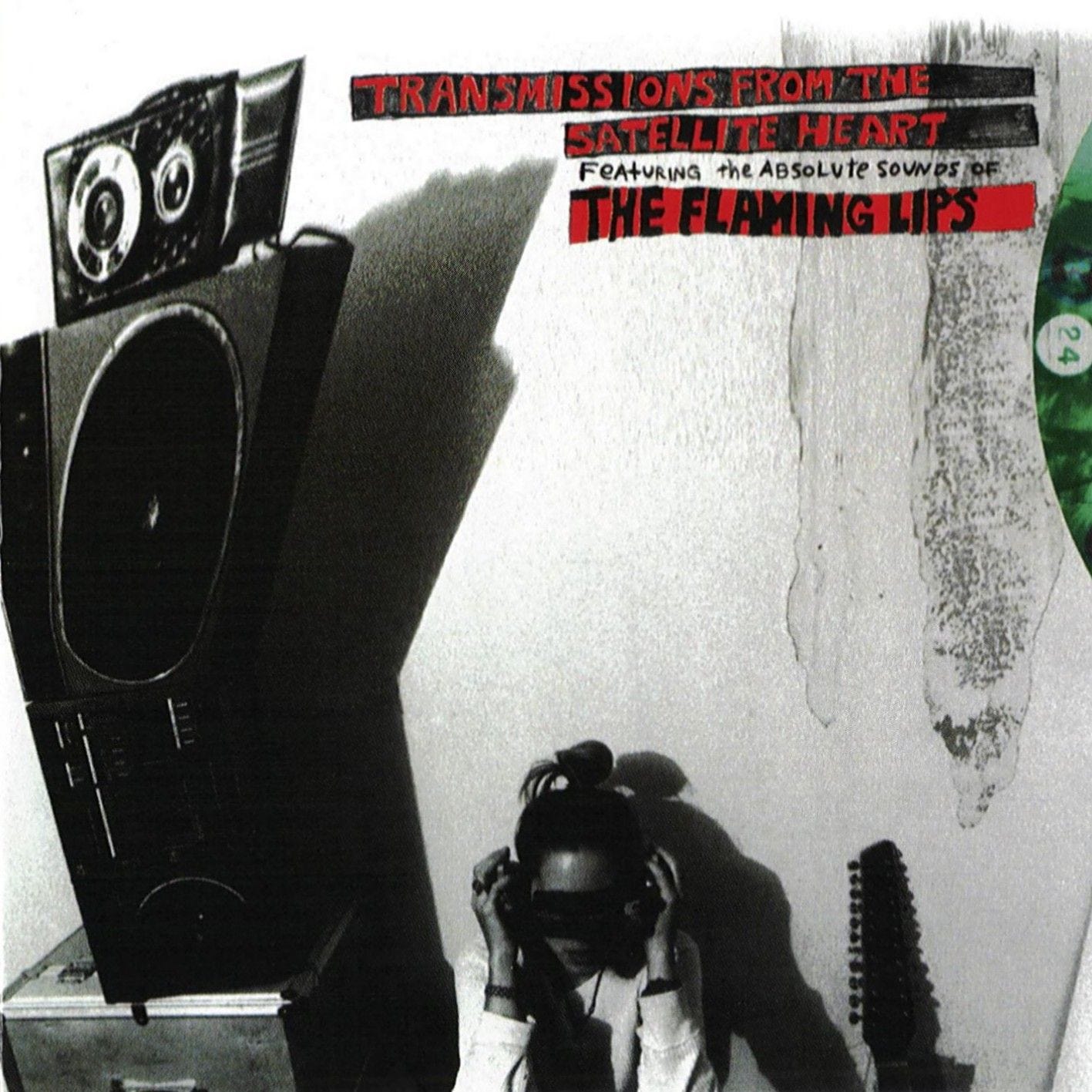

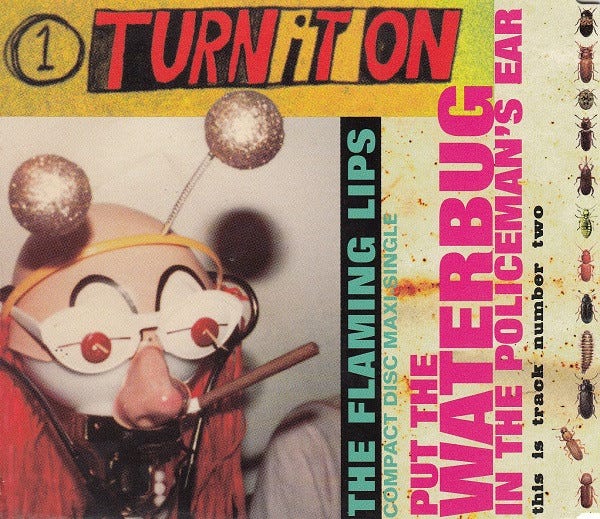

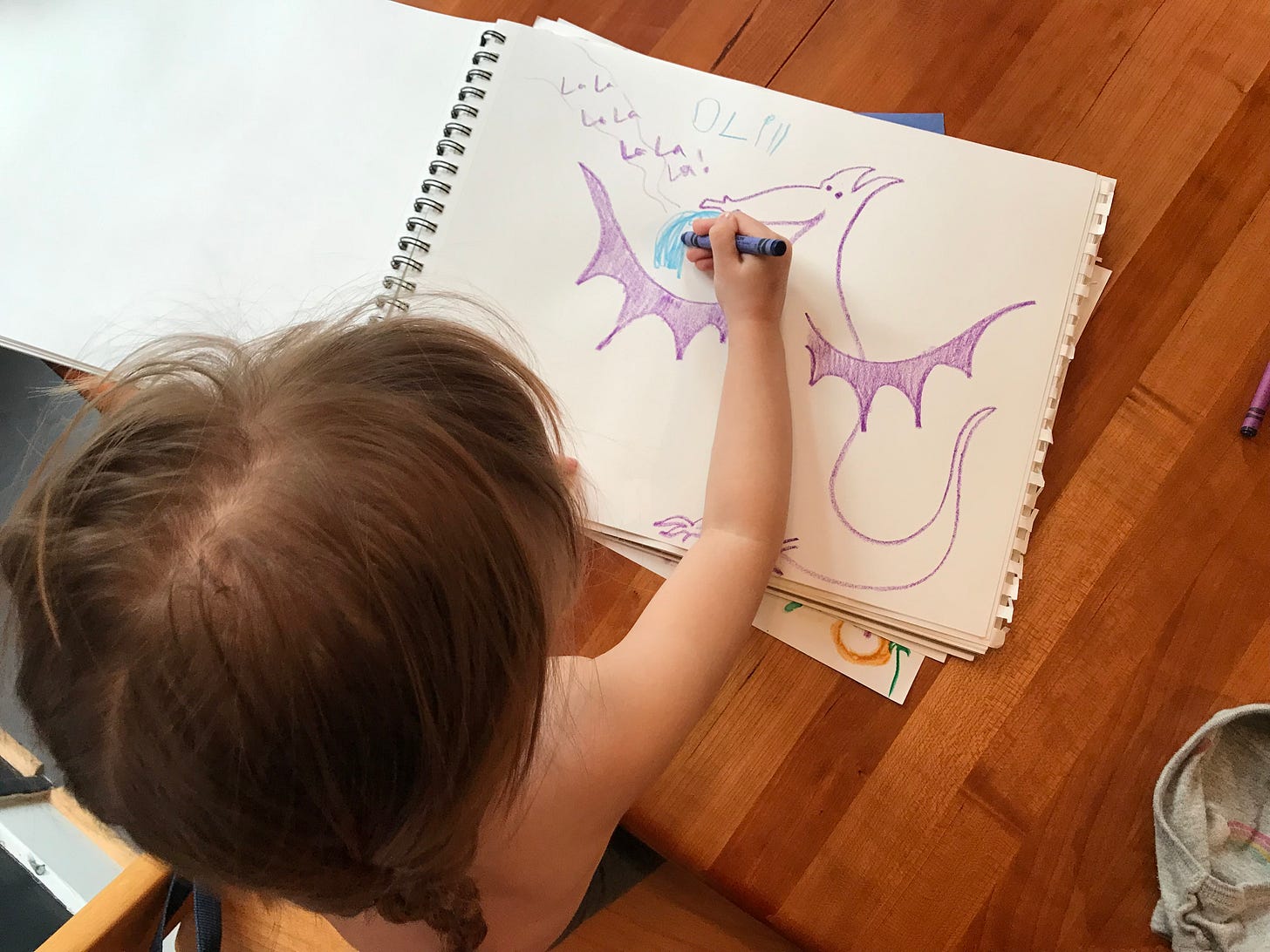

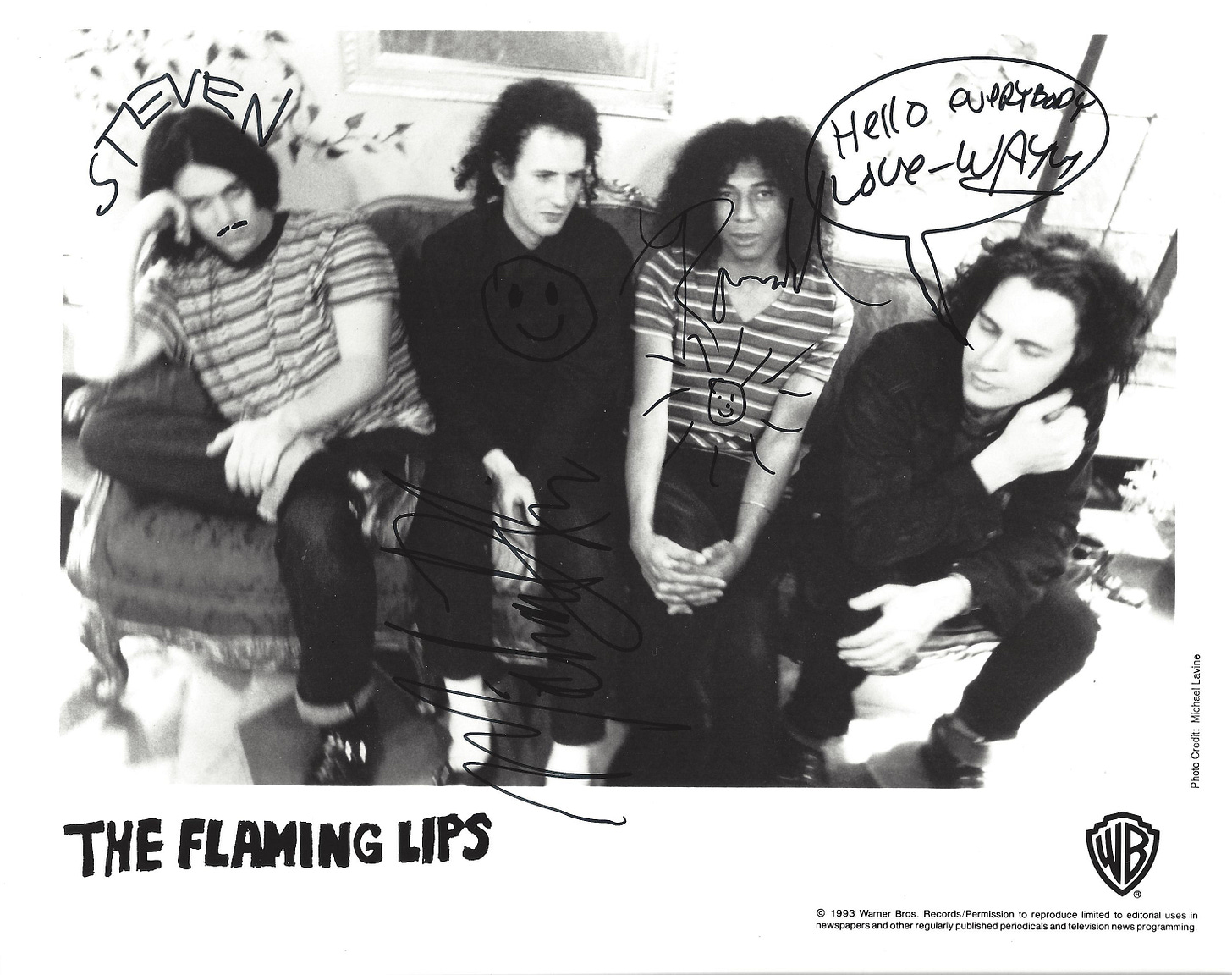

On a hot July afternoon in 2021, a few days after my daughter turned four, I played her The Flaming Lips for the first time. Naturally, I started with my first two Flaming Lips favorites: “Turn It On” and “She Don’t Use Jelly.” We’d just bought a whole cat family of Calico Critters and shared some cold drinks outside of the co-op, and the co-op experience made me nostalgic enough to play nostalgic music. The Flaming Lips released “She Don’t Use Jelly” on their album Transmissions from the Satellite Heart in June 1993, when I was 18. I started going to co-ops in college in 1994, the same year “Jelly” became a big hit and introduced countless kids like me to The Flaming Lips.

As my daughter stared out our van’s window, pondering “She Don’t Use Jelly” while we cruised down the street, she finally said, “What’s he singing about?” I explained: It’s a silly song where people do things they wouldn’t really do, like use Vaseline on toast instead of butter, and wipe their noses with magazines. She laughed and said, “Why does she use Vaseline instead of jelly? That’s yucky for her.” She quickly learned the melody and certain lines, and after the song ended, she kept singing to herself: “Maaaaaaa-gazines!” When we parked and walked to a restaurant for dinner, I held her in my arms, and together we sang “Taaaaangerines!” Technically, the song is about peoples’ idiosyncrasies, but it’s a joke song. It’s not supposed to make sense. Neither is the band’s early catalogue. Their whole aesthetic could be described as “lysergic idiosyncrasies.” When Lips singer Wayne Coyne hears their early albums now, he doesn’t even recognize himself. Oh my God, he thinks, this is insane. What are they doing? I feel the same way about my first two years of college as an apathetic art student. To me, Transmissions will always remind me of that brief, lysergic time.

On paper, The Lips should never have been popular, let alone built a 30-year musical career that continues to this day, but they are the perfect example of how little record labels knew about what would get popular in the early ’90s, and what would get ignored. The Lips weren’t remotely commercial when Warner Bros. signed them with a seven-album deal in late 1990. But back then, weird underground bands like Jane’s Addiction, The Cure, Butthole Surfers, and Sonic Youth had gotten popular with young people—bands with odd clothes and unconventional song structures. After Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” hit big in 1991, so-called underground music turned the old commercial musical rule book upside down. Radio stations changed their format to alternative. Big record labels like Warner and Sire signed a dizzying number of alternative bands in search of the next Nirvana, hoping to strike gold a fraction of the time. From greased rockabilly haircuts to flowers painted on nipples, kids had always liked weird things, but now weird bands were the new lucrative thing, and corporate labels couldn’t tell which weird bands would resonate enough to make them a lot of money. It’s funny to think of middle-aged music executives trying to sell kids something cool when so little connected these two demographics. But the execs provided the product to the teenage consumer, and they had younger, cooler A&R representatives find the bands. No one knew which green-haired band with nose rings were too weird to sell or just weird enough. How weird would young consumers go? Would the weirdness last? Were weird bands durable goods? Anything could work, like this joke song about Vaseline-covered toast: Who would have ever predicted that would hit? The Lips embodied why huge labels spent so much money during the alternative era. Spin magazine called The Flaming Lips’ deal with Warner “one of the strangest and most rewarding indie-to-major label relationships in pop-rock history.”

The Lips also embodied the risks of only landing one bit hit. But back then, Wayne Coyne described them as “a not-very-successful, weirdo rock group” who felt like every other ’90s alternative band. “We’re going to dropped from our record label,” Coyne said in a Pitchfork documentary. “We’ve had one hit single. And our main musician, our genius musician, is also a heroin addict. You could just look ahead and be like, ‘How you think this is gonna work out?’”

Despite the odds, it worked out well.

Brothers Wayne and Mark Coyne started the band in 1983 to play a punk show at Oklahoma City’s Blue Note club. The brothers lived in the nearby city of Norman and had gotten into punk and underground music.

“Me, I always wanted to be in a band,” Wayne Coyne told Option magazine in 1995, “but I could never figure out how to do it. I saw the Who and was like, ‘Wow, how do you get to do that for a living? Fuck!’ It wasn’t until we saw the hardcore shows that we figured out how to do it. We’d say to ourselves, ‘These guys pulled up in a van. We could do that. These guys have little amps. Same sort of amps we have at the house. They just do it all themselves.’ We were like, ‘I see! That’s cool!’ And we talked to them and said, ‘How’d you guys make records?’ And they said, ‘Saved up money and did it.’ And we’d go, ‘Oh, I see! We could do that!’ Before that, I thought you had to belong to some club or something.”

The little Blue Note club agreed to put The Lips on the bill that night, partly because the Coyne’s dad owned a shop next door. “We would rehearse in the meat locker in the back,” Wayne remembered.

The first time that Coyne’s friend Michael Ivins rehearsed with them in there, their appearance confused him. “I thought it was kind of weird,” said Ivins said in Jim DeRogatis’ biography Staring at Sound, “because it was almost, sort of like a punk-rock outfit, but here was this guy with this long hair tied up in a ponytail, almost like a hippie.”

Ivins had what people described as “an albino Goth look,” wearing eyeliner, black clothes, and a towering, frizzy, New Wave hairdo, and he had no friends.

Ivins agreed to fill the bassist slot for the gig even though he didn’t know how to play bass. “It was our first show,” said Coyne, “so everybody that we knew, we demanded that they come pay the three dollars charge at the door or something, so we probably walked out of there makin’ 50 or 60 bucks.”

Coyne and Ivins became tight.

“I just thought [my look] was oddly, inherently cool,” Ivins said in Staring at Sound, “but it wasn’t like I was trying to impress anyone. That’s the weird thing: I don’t know what I would have done if anyone did pay attention. Looking back, it seemed like it was this weird, personal, individual journey that really didn’t have anything to do with the outside world—the dressing up, the music—because I never knew anyone liked that kind of music until I met Wayne. It was like I was living out this weird fantasy, hoping to be a part of something.”

Oklahoma City’s location on U.S. 40 meant that many bands played OKC shows on their way to other cities. “Back when we began, me and [bassist] Michael [Ivins], we’d be the guys who’d bring the P.A. at the first Black Flag show. We did it for free, because we wanted to see the bands. We’d be the only guys with hair, you know? We weren’t stupid, we knew we had long hair and that those people didn’t like people with long hair. But we’d look around and go, ‘We don’t care, the music rocks.’ We liked it. And I always thought, well, how weird! I mean, how can people who like music say, ‘This is the friend and this is the enemy?’” In the eyes of the punks, Wayne’s long hair made him either a metal-head or a hippie, neither of which were good, but he saw no meaning in stylistic divisions, whether it David Bowie or Black Flag or Pink Floyd. “To me, it’s all music. I don’t care where it comes from.” That was the true spirit of punk.

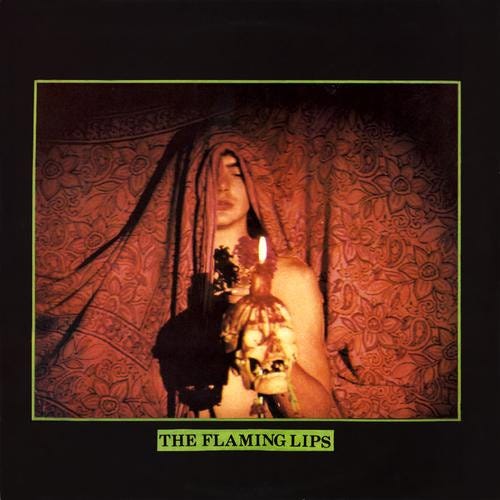

Applying that punk approach to their lives, they released their debut EP, The Flaming Lips, by themselves in 1984. “We didn’t know what record companies were,” said Coyne, “we didn’t know what getting signed was, we really didn’t think about those things at all.” The first song to hit listeners’ ears was “Bag Full of Thoughts,” a janky, noisy, psychedelic jam featuring moaning and nearly indecipherable lyrics. “Put your thoughts into a bag,” Mark Coyne groans. “If it becomes a drag / Throw it up into the air / Or give it away.”

Starting with “Bag Full of Thoughts” on through to 1995’s Clouds Taste Metallic, the band released scores of songs whose titles involved brains, heads, and the things that go on inside them:

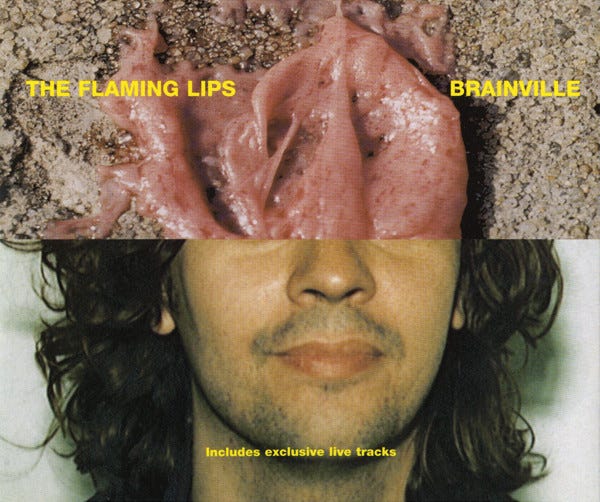

“Brainville”

“Trains, Brains & Rain”

“You Have to Be Joking (Autopsy of the Devil’s Brain)”

“Love Yer Brain”

“The Magician Vs. The Headache”

“Guy Who Got a Headache and Accidentally Saves the World”

“Placebo Headwound”

“Oh My Pregnant Head (Labia in the Sunlight)”

“Be My Head”

And of course, the album title Hit to Death in the Future Head

Mark left the band after their debut came out, and Wayne became singer.

Wayne had worked as a fry cook at a local Long John Silvers since 1977, at age 16, and he kept the steady money and flexible schedule while he built a life in music. The members of the touring bands that played OKC worked in warehouses and restaurants to subsidize their musical lives, so Wayne took the same practical approach, dropping fish filets in batter to subsidize his artistic freedom. “I never felt it was beneath me,” Coyne told the mayor of Oklahoma City in a TV interview. When classmates would ask Wayne why he worked in fast food rather than somewhere like Oklahoma’s lucrative oil rigs, he explained that it gave him the freedom to dream. “I don’t have a lot of money,” he’d tell them, “but I’m free.” He understood the need for artists to dream.

He also sold weed from the store, which allowed him to more than double his income. By the time he narrowly avoided getting busted, he’d used the money to buy a motorcycle, a new Gibson Les Paul, and small amplifier. “To me, it all really started to get fun when I bought the electric guitar and I could get loud and run it through wah-wah pedals and distortion and echo,” Coyne told DeRogatis. “After about a year of playing that sort of guitar, people started to be like, ‘I don’t know what the fuck you’re playing, but it sounds great.’”

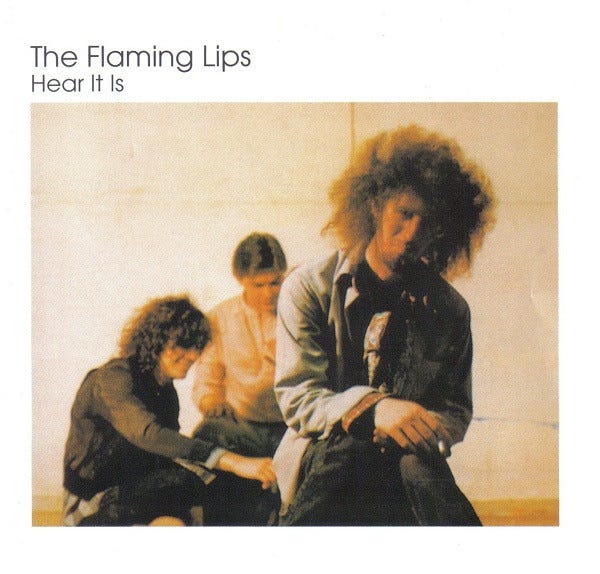

Then Restless Records swooped in to offer The Lips $2,500 to record their second EP in a Los Angeles studio with a Los Angeles producer.

A southern California indie label, Restless had released punk bands like 45 Grave, and The Dead Milkmen’s debut album Big Lizard in My Backyard. The Here It Is EP was Coyne’s debut as a singer. “It just seemed like an insane, great thing that we would get to go to L.A. and spend about 48 hours in a studio,” Coyne remembered.

I think the guy that was producing us thought we’d record a little bit during the day and then we’d leave and go get drunk or something, and he’d mix the record the next day and that would be the way it went. But we didn’t want him to mix without us there, and we kept recording and redoing things and doing overdubs and all that. I remember not sleeping and not leaving the studio, and we just stayed there and stayed there. At the very end of it, he had another session coming and gave us a cassette tape to listen to on the way home.

We drove all the way from Los Angeles back to Oklahoma City listening to this record that he had mixed, and I remember we hated. “Oh my God, how could he make the songs that way?” We were all so brain-dead from not sleeping and being so scared and exhilarated all at the same time. I think that spurred us, probably more than anything, to wanting to make records ourselves after that.

The song “Jesus Shootin’ Heroin” I think we wanted to appear to be menacing and deep and represent some dark, unspeakable version of life in the Bible Belt or something like that, even though us as the Flaming Lips, we never considered the Bible or the Bible Belt or being in a religious state like Oklahoma. We never really cared, we never really thought about it. But in “Jesus Shootin’ Heroin,” we thought it would make people think that we were crazy and menacing and drug addicts or whatever, even though we really weren’t. It’s a long song. I remember it being sort of dirge-y, and I think it’s in E minor or something like that. When I hear it now, it doesn’t sound anything like The Flaming Lips that I remember, and I really like it. It’s just such a strange, strange song and I could understand why people would think that something is going wrong and we’re weird and we’re pretentious all at the same time.

If anything defined their earliest years, it wasn’t a particular sound. It was determination and constant change, and maybe a fixation with religion, psychedelics, and goofing around. Their music evolved as they aged, but age didn’t change their warped sense of humor on early albums like Oh My Gawd!!!...The Flaming Lips and Telepathic Surgery. While Coyne kept dropping fish fillets in batter, The Lips wrote songs that made them seem like they dropped acid 24-hours a day, and they performed frequently, even opening for The Butthole Surfers in Texas around 1986, and Jane’s Addiction around 1988.

“Visually, they were really entertaining,” someone said in the documentary Fearless Freaks. “It’s just, the songs weren’t so great.”

Back then, the band mostly excelled at guitar riffs and cool song titles like “One Million Billionth of a Millisecond on a Sunday Morning,” “Hell’s Angels Cracker Factory,” “The Last Drop of Morning Dew,” and “Shaved Gorilla.” (“We got a gorilla / And we shaved him / And bought him a motorcycle.”) If you had to describe their sound, you could call it a weirdo-art-noise-acid-punk. They weren’t punk because they played fast songs. They weren’t punk by being, as the Dead Boys album put it, “young, loud, and snotty.” They were punk because they did things their way, which is the true meaning of punk. They talked about tripping on acid back when most punks dismissed acid as a hippie thing. And they were so excited when punks started taking acid that they named a whole album Finally the Punk Rockers Are Taking Acid. In concert they covered Neil Young, Led Zeppelin, The Stooges, Echo and the Bunnymen, Galaxie 500, Scratch Acid, and Dream Syndicate, all before 1990—stuff that wasn’t always cool, but stuff that proved they had impeccable taste. Their original music mixed elements of Pink Floyd, The Beatles, Sonic Youth, The Sonics, and The Kinks all processed them all through Wayne’s weird lyrical universe of insects, robots, brains, and malfunctions. If Bad Brains had asked “How low can a punk get?” The Lips were asking “How much less punk could you get?”

Speaking of punk, some people say that The Lips’ music and stage show were heavily influenced by the 1970s punk band The Debris. Hailing from Chickasha, Oklahoma, The Debris released one of the first punk records in the U.S., in 1975, called Static Disposal, reformed in the late 2000s, were inducted into the Oklahoma Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but they never recorded again, and they didn’t get credit for their influence on Coyne. Coyne was a sponge. He pulled from what he liked and what was around him.

Maybe they weren’t a great band yet by conventional standards, but they were memorable, and they were heading toward an epiphany.

Their 1989 album Telepathic Surgery rocks on the outside, but it doesn’t stay with you. Some guitar riffs are wicked. The guitar tone is killer. The songs “Drug Machine in Heaven,” “Right Now,” and “Hari-Krishna Stomp Wagon (Fuck Led Zeppelin)” are a little bit Mudhoney, a little Guns N’ Roses. It’s the kind of music that would impress you in concert, but your enthusiasm would cool listening to the album back home. So The Lips compensated for their limited musicianship by building their song “Chrome Plated Suicide” from Guns N’ Roses’ “Sweet Child o’ Mine,” and by creating elaborate stage shows that included Christmas lights, bubbles, smoke machines, a leaf blower that showered the audience with confetti, setting small fires, and a sense of excitement that convinced listeners that they were a killer band to see. “When you suffer in other areas,” Wayne’s brother Mark said, “you try to make up for it with the show.” I felt the same way about my fellow college art students’ clothing: the more dramatic their outfit, the less impressive their creative output. Many of us were compensating, muddying our waters to appear deep. For The Lips it worked.

Warner Bros. signed them in 1990 after an A&R rep watched the band nearly burn down an American Legion Hall during the show’s first song. The Lips decided to try to impress Warner with an incredible performance, so they lit an upside-down drum cymbal on fire the way the Butthole Surfers did at their wild shows.

“If we had rehearsed it, they wouldn’t have let us play. So we just simply did it at the beginning of the set and he kept bashing away, and the fire was jumping everywhere,” Coyne remembered. “Fire is hitting the ceiling and the lighter fluid that we were using was running off onto the stage, which had really old carpeting on it, and all that was catching on fire.”

One of Wayne’s brothers realized This is getting slightly out of hand and sprayed the stage with a fire extinguisher. The chemical cloud filled the tiny club. The audience thought the smoke was part of the show and it amped them up further. Warner loved it.

Wayne quit Long John Silvers in 1990, after Warner signed them. The Lips’ music also turned a corner, thanks to the combined musical sensibilities of Coyne and lead guitarist Jonathan Donahue, who played in a shoegazey noise band called Mercury Rev and brought that visionary energy to the album. The songs they released on their last album for Restless Records, In a Priest Driven Ambulance, were thematically linked around Coyne’s interest in religion. The Lips hail from the Bible Belt, after all. Sonically, the album was powerful stuff— psychedelic, jangly, noise-rock that had catchy sections and hints of pop music—but their next album was even better.

Warner released the Lips’ major label debut, Hit to Death in the Future Head, in 1992. Option described their sound in this era as a “sonic DNA experiment, recombining grunge with some old acid test.” That definition definitely captured songs like “Talkin’ ’Bout the Smiling Deathporn Immortality Blues (Everyone Wants to Live Forever)”—music whose “potent pop sensibility” got locked in what Option called “a distorted, Floydian vortex.” Hit to Death in the Future Head is expansive and promising, and “Halloween on the Barbary Coast” and “Hit Me Like You Did the First Time” were the kind the band could’ve kept playing their entire careers if they chose to.

Also: They got signed to fucking Warner Bros, one of the biggest entertainment operations in history. How exciting. Things were happening. Now they were part of the big music industry machine that had money and marketing muscle! Coyne’s impractical dream was manifesting. Instead of frying fish, he could sing about that life in later songs like “Bad Days”: “And you hate your boss at your job / Well in your dreams you can blow his head off / In your dreams, show no mercy / And all your bad days will end.” But the bad days never end. Their lineup changed again.

Despite major label backing, The Lips’ lead guitarist Jonathan Donahue and drummer Nathan Roberts left the band. Donahue rejoined his other band Mercury Rev. Roberts just quit. “We would play all the time, and [Roberts] was just not built for that,” Coyne said. “He liked the idea of going to work, and then when he got off work, he could lay around and watch movies and get drunk, and he would have weekends free. In fact, it was just not in his personality to be ‘the road warrior creative person.’”

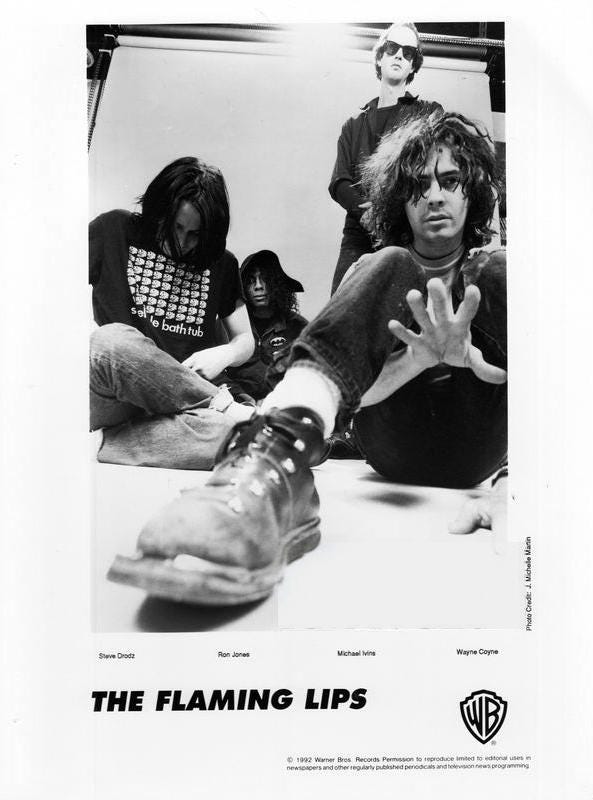

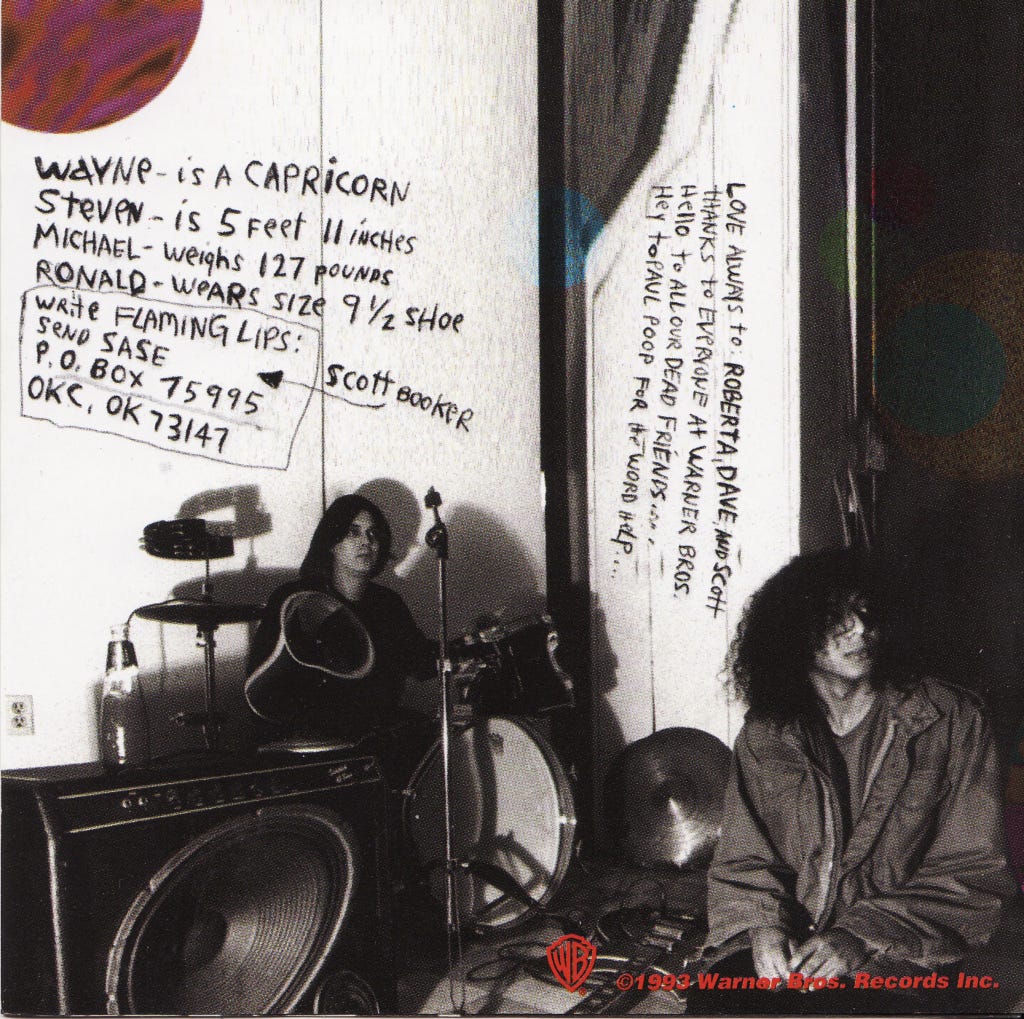

The Lips were a full-time affair, so Coyne and Ivins replaced Donahue and Roberts with two musicians who proved to be some of the best they ever had. First came drummer Steven Drozd.

Someone tipped off Coyne about a killer drummer who played in a bad Norman, Oklahoma band, saying “You know, Janice Eighteen still sucks, but their drummer is amazing.” The drummer, Steve Drozd, grew up in the ’70s playing along to bands like Led Zeppelin, Kiss, The Who, and Aerosmith, and he was particularly drawn to heavy, big booming players like Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham. After hearing In a Priest Driven Ambulance, The Flaming Lips became one of his favorite bands. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” Drozd said. In fall 1991, Coyne and Ivins invite him to jam up in OKC. He turned out to be a brilliant multi-instrumentalist and songwriter who jived with them immediately.

“Almost anything that I like, he likes,” said Coyne, “and everything he hates, I hate. We are on the same wavelength all the time.” Drozd also liked The Lips’ approach to making music. “I think the way that we were making our music and making records,” Coyne told Consequence of Sound, “he was like, ‘Man, I want to be in a group like The Flaming Lips.’ So when we needed somebody, he was already there.” Drozd appreciated the creative carnival atmosphere. His talent was matched with ambition, so he was driven to make it work.

“He liked Wayne and wanted to be part of things and wanted to work with him,” Coyne’s mom said in Fearless Freaks. “He can play the things that Wayne can’t play.” Although a heavy-hitting drummer, Drozd could play nearly any instrument. And he could write songs, write song parts, and help arrange songs with a sophisticated the others lacked.

“I could never write lyrics,” Drozd told Modern Drummer, “but I always had melodies flying around in my head. Wayne Coyne is an amazing lyricist. So I can play him a set of chord changes and a melody, and he will come up with words to bring the song to life.”

Even though Coyne didn’t have a classic singers’ voice, he had the perfect voice for this band, a beautiful, sweet, fragile egg of a voice that wobbled over the melodies, careless and happy.

Coyne called Drozd the genius of the band.

Others later said Coyne was lucky to have found him, because otherwise where would Coyne have ended up?

“I think he saw in us, ‘Hey, if I got in there, I could help them be a little more emotional, a little bit more rock, a little bit more experimental,’” Coyne said. “I think all the things that were happening, he saw he could step in and make all that work better. In the beginning, I don’t think I could’ve been aware of that. I thought he was a really, really great drummer, and we needed a drummer, and so he joined.” Drozd had a different sensibility that moved the band into greater depth than songs about acid, freaks, and headaches. “And I think, little by little, we just played off each other’s strengths here or there. Certainly me and Michael, we can’t play very well, but we have other qualities that we hope are of some value to the organization.”

Like Drozd, the band’s new lead guitarist was already there in their circle, waiting in the wings.

When Donahue left, their guitarist-DJ friend Jon Mooneyham stepped in on guitar. He didn’t stay long. In early 1991, during the Hit to Death in the Future Head era, an incredible psychedelic guitarist named Ronald Jones had started hanging out around the band’s rehearsals and residential duplex, and talking with their manager Scott Booker, who worked at a local record store. The Lips were one of the most exciting things happening in Oklahoma City at the time, so other young, restless, musical freaks gravitated to the carnival. Jones worked at a grocery store and was just another kid looking for something to do.

Initially, he had the same reaction as Drozd. “Ronald had seen us play,” Coyne remembered, “and he was like, ‘Man, I wish I could be in a group like this!’”

“When [guitarist Jon] Mooneyham was practicing with us, [Jones] would come by every day and watch us rehearse,” Drozd said in the Fearless Freaks documentary.

“He wanted to watch you guys practice and stuff,” Scott Booker remembered. “I mean, he would come back to the record store, ’cause even though I was managing you—let it be known—I still worked at the record store for a long time. He would come back and tell me [how practice went] and I’d be like, ‘Well, how was it today?’ He’d kind of shake his head like Mmmm.”

Although they got to know Jones during Mooneyham’s brief tenure, they didn’t realize how well Jones played guitar.

One day Jones came to the band’s duplex and played their song “There You Are,” from In a Priest Driven Ambulance, on a cheap acoustic guitar. He asked Coyne if he was playing it right. Coyne told him, “Yeah, except you’re playing all the parts at once.” Booker watched the exchange and thought, Hmm, if Jon doesn’t work out, maybe this guy wouldn’t be bad.

As a quiet talent, Jones could hear Mooneyham’s musical limitations, but he didn’t want to say anything too critical. First off, Jones didn’t know these guys that well. The band members were all friends, fused by membership in a long-standing group with a rep and a record label. He was still an outsider, so he was probably being diplomatic, cautiously stepping in without stepping on many toes. Coyne believes that Jones’ nice side kept him from saying anything critical about Mooneyham or any other people. “He had another side of him that was very strange, and no one could predict,” Coyne said in Fearless Freaks. Jones was difficult to record with and perform with and get close to. He was mysterious, but that was part of his musical power. “But when we first met him, he was a unique, innocent, strange child-man.”

When Mooneyham left, the band had Jones jam with their new heavy-hitting drummer. “He came in,” said Coyne, “and immediately Ronald and Steven playing together, within the first five minutes it’s like, ‘Oh man, this is pretty fun,’ mostly because I don’t play very well.”

After all those line-up changes and youthful amateurism, this talented guitarist had showed up on their porch like a hungry feral cat, and his brilliant, singular style was demented enough to fit The Lips’ warped music and propel them into a new, powerful phase.

Like the rainbows shooting from the child’s eyeballs on the cover of The Lips’ 2009 album The Dark Side of the Moon, good-weird ideas shot consistently from them. This lineup is considered the classic early Lips lineup. “Suddenly we found this great rock sound,” said Coyne. “And we were gonna, you know, I suppose at that time we thought that we could make 20 records like that, or whatever.” As they wrote the songs that would become their breakout album Transmissions from the Satellite Heart, Coyne, Drozd, and Ivins forged a relationship that has outlasted all the subsequent musical iterations they would live through.

“The group that started off with the Transmissions from the Satellite Heart album really opened us all up where anything felt possible,” said Coyne.

“Ronald Jones was an incredible guitar player,” said Drozd. “He could play any kind of guitar, but the stuff he chose to play was a cross between electric Miles Davis and Kevin Shields or somethin’.”

“Steven and Ronald, as such, were master musicians compared to what we were doing previous to that,” Coyne said about the band’s new abilities. “Steven and Ronald could play with Miles Davis. They could write music with Igor Stravinsky; they are at such a high level. By being with them, we immediately jumped into a different category; there would be this rich, childlike sound that I would be able to bring to the group, but then there was this emotional, beautiful, and delicate stuff that Ronald and Steven started bringing to the group. We started to do the stuff that we were only previously able to dream about.”

Unlike Coyne and Drozd’s psychic connection, though, Coyne and Jones were not on the same wavelength. Nobody was.

“I mean, Ronald was very much on his own trip,” Coyne said, “which we loved.” That trip was Jones’ musical strength. Jones played vintage guitars through lots of effects pedals, and often made squealing sounds using a slide, and crackling explosions to accent certain musical transitions. Biographer Jim DeRogatis called him a “disorienting one-man orchestra.” Jones heard things differently, and he added unique layers to the band, often creating a kind of buried, humming, laser beam orchestration behind Coyne’s guitar. In the studio for Transmissions, he sometimes took a few days to construct a guitar part that only lasted in a song for twenty seconds. Like his playing, Jones also thought very differently than most people, which made him difficult to work with and relate to, and that different wavelength eventually worked against the band when he suddenly quit. But for now, it helped define Transmissions.

Although Coyne loved Jones’ “freak, genius, eccentric” guitar playing, he admitted he “didn’t always understand what he was doing.” “But Steven and Ronald had a very musical language together,” Coyne said, “and Steven would encourage Ronald to be even weirder than Ronald would even think to be. Them together really accelerated the musical weirdness of what the Flaming Lips were capable of, and at the same time heightened what I feel is the emotional part. So though it’s getting weirder, you’d have to know a lot about how music works to really know why it’s weird.”

Because lead guitarist Jonathan Donahue left right when they released Hit to Death in the Future Head on Warner, Jones stepped into play those new songs on their 1992 tour. That Donahue lineup had great energy live, because he’s an imaginative guitarist. Listen to Donahue’s angular guitar accents live on “My Two Days As An Ambulance Driver (Jets Part 2)” on their 1992 John Peel session. He was a skillful, artful noisemaker, but Jones was even better at it. The Jones-Drozd lineup was so good that when they played old songs, they reanimated them, bringing new life to the band’s existing catalogue. Studio versions of songs that were good on record became powerful psychedelic jams. If the studio versions of “Let Me Be It,” “Talkin’ ‘Bout the Smiling Deathporn Immortality Blues (Everyone Wants to Live Forever),” and “Halloween on the Barbary Coast” only sounded like the live 1992 and 93 versions, Ambulance and Future Head might be as classic as Transmissions.

The studio version and 1992 Peel Session version of “Hit Me Like You Did the First Time” are good songs with great bones: catchy, fast, rocking. Then they’ve got that weird electric distortion bridge. But live, Drozd lights that song up to another level, with his sense of dynamics changing the whole thing. And Jones’ lead guitar turned a good song into a great one, electrifying it with fiery patterns, prog rock moments, and many squealing, sideways, psychedelic accents. I wish they’d recorded a version of it in the studio playing like that for maximum fidelity. Thankfully we have some powerful audience recordings of varying quality and two crystal clear soundboard recordings, including one from one of the last shows Jones played with the band in 1996.

For the casual observer listening to “Jelly” on the radio or MTV, it was easy to miss Jones’ guitar wizardry. Thankfully, a fan who actually plays guitar examined Jones’ guitar sound and equipment, and he identified a few elements of Jones’ style as “slide guitar, pick scratches, musical ring modulation, crazy synth, fuzzed-out leads, orchestral and otherworldly delays and reverb.” Like me, he heard what he called “Ronald’s guitar witchcraft” most clearly in recordings of 1995 and ’96 shows, which he considered “the pinnacle of psychedelic noise rock weirdness.”

When you watch Jones in footage—really watch him—you see his hands hard at work, and you see him making his signature squeals by dragging both his picking hand and his left hand down the guitar’s neck, often suddenly aggressively, as if he’s trying to severe it. It’s magic.

Jones’ guitar solo on “Bad Days” live is one of the most inventive, urgent, captivating solos from any ’90s band, hands down. Listen to it live in Ventura in 1995. And watch him play it here NYC in 1995. I wish it went on forever.

With their new chemistry, they started writing new music together that would be their next album, Transmissions from the Satellite Heart. This was their chance. The world was hungry for alternative rock, and Warner was waiting.

Sometimes the band wrote around sketches Drozd dreamed up, or little melodic lines Coyne had. Other times they wrote songs around Drozd’s drumbeats. “Our song ‘Slow Nerve Action’ was like that,” said Drozd. “I recorded this extremely distorted part on a four-track machine. We wrote that song around that because we thought it sounded so cool.”

One day, Coyne was strumming his acoustic guitar, playing with ideas. A simple song came out of Coyne over the course of a few minutes. “Before I’d even made a demo of it, I played this little thing, probably in the exact same chords that’s still there,” Coyne said. “‘I know a girl who...’ It did this little twist at the end and says she uses Vaseline, and I remember playing that for Steven. It felt like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s absolutely going to work.’” When he recorded a demo, he used a simple acoustic guitar. “Back then, I would do the crudest of demos, just with an acoustic guitar, sometimes an unplugged electric guitar, and I would sing it into a tape player or something, whatever we had,” he said. “Then we were doing a lot of recording and just barreling through a lot of great big arrangements and all that. ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’ was catchy and quirky and all those things, but all the songs on that record we felt were already. ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’ didn’t stand out as being one way and other songs were another way, but then it started to gain a momentum of its own.” Only later in the studio, did Jones add that definitive electric slide guitar part, and the sound of a decade was born.

As they recorded what would be Transmissions in the winter of 1993, I was finishing my final year of high school. As I searched for my own voice and identity as a teenager, the band had found their own.

Dave Fridmann, who engineered and produced The Lips’ two previous albums, got a copy of a six-song tape containing early mixes of Transmissions. He and his friends in the band Mercury Rev drove around in their van listening to the tape. “And we were all just listening to songs like that’s cool, that’s cool, that’s cool. And then ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’ came on and I was like, ‘Holy crap,’ they actually wrote a song that could do something here.”

The band released Transmissions from the Satellite Heart in June 1993 and toured the Midwest and South that summer. Their dissonant guitar style is on perfect display in this soundboard recording from the Varsity Theatre in Baton Rouge on September 29, 1993. It slays.

They start the show with a raging version of “Mountain Side.” The sad beginning of “Moth in Incubator” is absolutely crushing, with its minor keys and strained vocals. Their simple extended end on “Chewing on the Apple of Your Eye” crushes the already beautiful album version. And the raucous finale to “Oh My Pregnant Head” is the best version I’ve heard.

They needed to perform at that level to get this weird music across to people. So after MTV declined to play the video for their first single “Turn It On,” they toured relentlessly to get the word out and show Warner Bros they were serious.

“Though well-received critically,” Option magazine wrote, “Transmissions from the Satellite Heart was released with relatively little fanfare.” To Option, even with the band’s small devoted fanbase, “no one seemed to be paying any attention.” They played “Turn It On” and “Jelly” in concert for the first time at Raji’s in Hollywood, on June 4, 1993—the club where Charles Peterson famously took the photo of Kurt Cobain jumping backwards onto Chad Channing’s drum set. And then, shortly after Warner released the single and video for “She Don’t Use Jelly” in October 1993, the popular cartoon Beavis and Butt-Head lambasted it on MTV, which got alternative radio stations to play the song more and gave the album the attention it wasn’t earning on its own.

Beavis and Butt-Head were idiots. They sat on a couch, critiquing the art other people had the confidence to perform publicly. As The Lips banged their instruments in a city park on MTV, Beavis said, “Uh oh. I think this is college music.”

“You can also tell it’s college music ’cause, it’s like, they’re in a field,” Butt-Head said.

“Yeah,” said Beavis. “Fields suck. How come he keeps singing about these people he knows? Who gives a rat’s ass.”

Butt-Head sang: “I know a guy. His hair is orange. He sucks!”

That’s the part you were supposed to think was funny, but The Lips didn’t suck, and this particular joke was getting tired by ’93. And yet, the publicity worked.

Beyond the show’s high-profile lambasting, the dumb nonsense song was super catchy, and that combination of fun-singalong and easy-to-hate helped push it through the blood-brain barrier of popular consciousness, moving The Lips from the weird musical underground into the mainstream commercial showcases where record labels hoped all their bands would end up. During the Alternative Era, that counted as success.

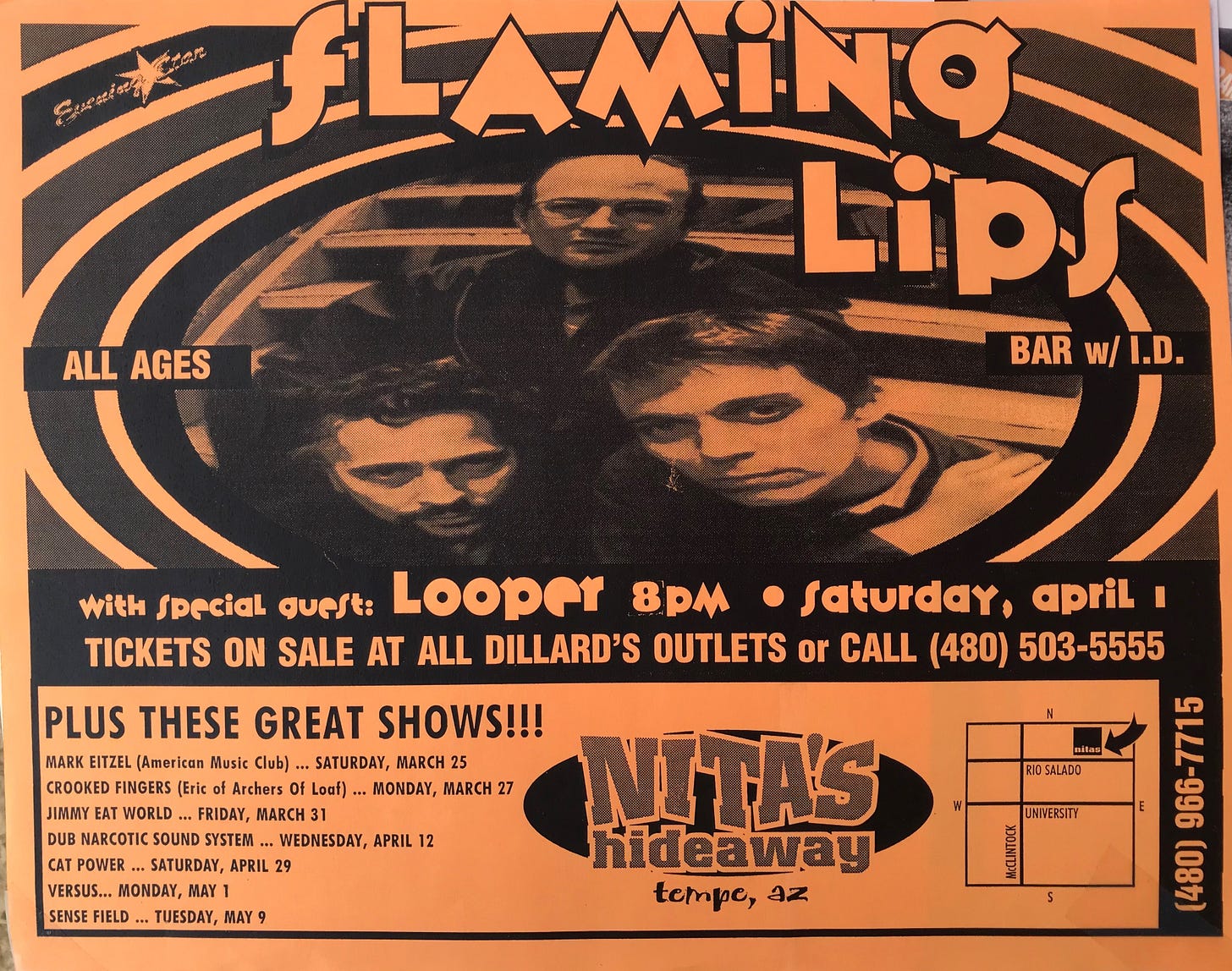

Between 1994 and ’95, The Flaming Lips played “She Don’t Use Jelly” everywhere. They played it on Late Night with David Letterman. They played it on The Jon Stewart Show. They played it on the popular schlock Beverly Hills 90210, and on some obscure show called JBTV, and on the 1995 installment of MTV’s hugely popular Spring Break show on some beach somewhere, with that idiot host Pauly Shore dry humping the stage as guitarist Ronald Jones let his signature distortion crackle from his surf green vintage 1960s Fender Jaguar. The Lips even played ten cities on the second stage of the Lollapalooza 1994 tour—unfortunately not in Phoenix where I lived. “They were the all-out favorites of critics, fans, and other bands,” said Option magazine, “often joined onstage by members of the Bad Seeds and L7.” The song reached number 55 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100. It became an actual top 30 hit in Australia. On the strength of “She Don’t Use Jelly,” Transmissions sold a few hundred thousand records. That wasn’t huge, but it was much bigger than anyone expected for this demented Oklahoma band, and way more than their previous records sold.

“The Lips were on a real high right at that moment,” Drozd said. ‘We had done the second stage on Lollapalooza and it seemed more and more people were starting to get us.”

The Lips reached me like they reached Beavis and Butt-Head: while I sat on a couch watching MTV with friends, critiquing lame bands like Live and Bush. I totally disagreed with Beavis and Butt-head’s dismissal of “Jelly.” The Lips’ acid-induced, comic aesthetic quickly came to define my warped young vision of life, and The Lips’ Transmissions from the Satellite Heart ruled my world alongside The Meat Puppets’ album Too High to Die and Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream.

Transmissions opened with a happy anthem called “Turn It On.” Upbeat and guitar-driven, this singalong combined a call to arms with the 1960s lingo of psychological liberation and psychedelic adventure. Turning people on meant introducing them to something—could be a band, could be a scene. By tipping people off, you enlighten them. In ’60s vernacular, the phrase also meant enlightened from LSD, so being “turned on” was code for those in the know after taking psychedelics. Timothy Leary famously said, “Tune in, turn on, drop out.” In 1967 Jimi Hendrix sang: “Are you experienced? Have you ever been experienced?” Others from that era asked “Are you turned on?” The Lips were. And in this song, they passed that ’60s lingo on to us ’90s kids, unashamed of its hippie associations the way some of us thought we should be.

Coyne sang:

Turn it on and all the way up

Turn it on, in your houses when you wake up

Turn it on, when you ain’t got no relation

To all those other stations

Turn it on!

The verses made little obvious sense, which I loved, but the chorus seemed to urge listeners to turn off commercial mainstream messaging in order to tune into our own weird station—a figurative station, some source of information—and to turn on the music of the underground, maybe even weird arty bands like them. It’s a smart way to start a new album: Give a generation an anthem.

Put your life into a bubble

We can pick you up on radar

Hit a satellite with feeling

Give the people what they paid for

“Turn It On” briefly became my anthem. I blasted it in my metallic blue, 1969 VW Bug on the drive to school. I blasted it alone while skating various concrete flood control channels that I found in suburban neighborhoods. I blasted it on headphones while getting stoned in the university parking garage after class. Musically, it felt optimistic, and it proved that this album and band were so much more than “Jelly.”

There are certain songs that you love the first time you hear them. “Turn It On” had a sound that could carry me somewhere new. It felt like forward momentum, like me evolving into a different person, one closer to the one I thought I would be.

During the time I jammed Transmissions, I wore a litany of clothes I found at thrift stores: vintage Ocean Pacific and Hang Ten shirts featuring faded blue waves and tattered logos, cut-off green army pants, gaudy green and orange Sex Wax and Orange Crush shirts. I smoked weed, drove that 1969 Bug with red plaid seats, and rode my vintage Logan Earth Ski cruiser board and my enormous Sector 9 Downhill longboard to class. As a textbook ’90s rock kid, I was supposed to hate hippies. But for a guy who hated hippies, I pulled a lot of my fashion from the late-60s and early-70s—specifically from the surf side of things, not the tie dye flower power side. The Lips’ art-band weirdness fit this period of my early college life, but their hippie-ish ways also nudged me from my indie rock comfort zone to truly expand my identity. I wasn’t comfortable acknowledging how much hippie was in me yet.

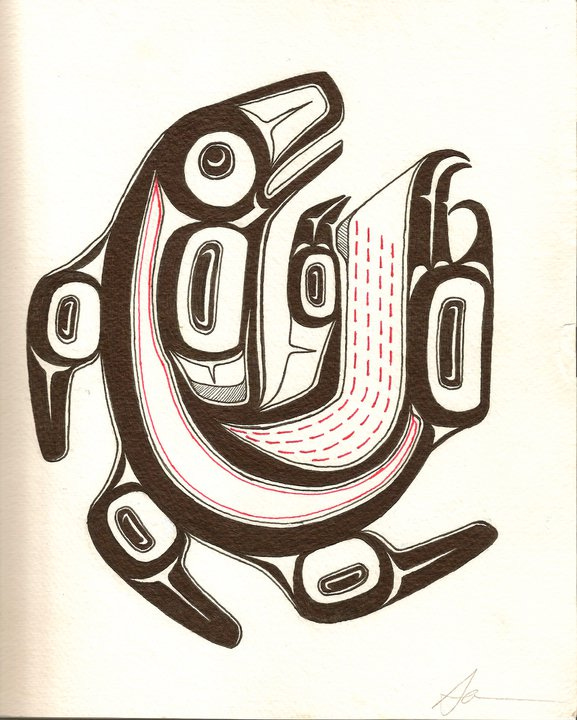

Every unique band and subculture have their own iconography and motifs. The Paisley Underground bands had paisley. The early Velvet Underground had striped shirts, leather jackets, and sunglasses. The Beach Boys loved Pendelton shirts so much that, before they became the Beach Boys, they called themselves The Pendeltons. I liked curling waves, beachy suns, palm trees, and flowers. Lately, I’d started picking flowers around campus to draw them during class. I picked flowers in the wild and stuck them in vents on my Bug’s dashboard like you would a vase. I even pressed real blossoms between notebook pages. I always negatively associated flower iconography with flower power Grateful Dead shit, so I hid my Naturalist love of them, but was I really going to let the hippie association ruin one of Nature’s greatest gift for me? Was I really so insecure that I couldn’t handle getting labeled a hippie? How sad. My VW Bug was from 1969 for god’s sake—69, the end of the Age of Aquarius, the year Altamont ended the era shortly after The Dead had left San Francisco for the countryside. Kurt Cobain’s disdain for The Dead reinforced my own. “I wouldn’t wear a tie-dyed t-shirt unless it was dyed with the urine of Phil Collins and the blood of Jerry Garcia,” Cobain once said. I liked that. And yet, many musicians who influenced Cobain, including The Meat Puppets, Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn, and Sonic Youth guitarist Lee Renaldo, were Dead fans. Not me yet. I resisted because I lived in an imagined rock ‘n’ roll silo, which kept those hippie people over there, and me in cool guy land over here. But when the orange blossoms bloomed on campus, I sat near the trees to study in a cloud of their intoxicating fragrance. Nature was slipping some wonderful hippie things into me, and my love of The Flaming Lips helped me quit resisting.

The Lips had peace signs, happy faces, skulls, and colorful squiggles all over—total hippie stuff. And so along with an influential young woman who’d recently taken me to eat at my first natural grocery store, The Lips helped dissolve my reflexive hatred of hippies and get me closer to embracing hippie-ish things that I was naturally drawn to, like Mother Nature, rainbows, flowers in my shirt pocket, and eating natural foods. In every sense, The Lips turned me on.

And The Lips brought weirdness to the masses.

“But popularity is a funny thing,” Coyne told Yahoo. “Once something is kind of popular, it has the potential to grow and grow and grow. When Beverly Hills 90210 called us, if this would’ve been, you know, a year earlier or six months early, we probably would have thought, No, we’re too cool, we don’t do those sorts of things. But we had just done a lot stuff by then, and it occurred to us that it would be ridiculous and absurd and funny, and it didn’t really matter if it was artistically good or bad or whatever, you know?”

I hated Beverly Hills 90210, so I never saw their performance until decades later, but the producers were trying to connect to the kiddos through popular music, and alternative music was so popular in 1995 that it was no longer alternative. At the characters’ favorite hangout, a diner called the Peach Pit, the band played a small stage covered in colorful Christmas lights, and the David Silver character leans over his friends’ shoulders and says, “Hey, is that The Flaming Lips?”

Without taking his eyes off the band, Steve Sanders says, “It’s not Michael Bolton.”

Silver was always trying to be popular. Here was his chance.

After the performance, Sanders tells his friend, “You know, I’ve never been a big fan alternative music, but these guys rock the house!” No cool kid would ever say “rock the house.” But that moment in that episode captured the central cultural dynamic in the early ’90s: the way capitalism turned underground freak music into products for mass consumption, and how regular kids did lots of things to be cool.

Although 90210 tackled serious issues like date rape, alcoholism, and pregnancy, the show’s characters were still the very upper middle class kind that didn’t seem drawn to underground rock during the first half the ’90s. They were the Boys 2 Men demographic, later the Backstreet Boys demographic. They didn’t drop acid and dye their hair with tangerines. They worked as a cabana boy to save enough money to buy a 1965 Mustang convertible, like Brandon did in Episode 1, Season 2. They acted out after earning low SAT scores, like Donna did. “You know, I’ve never been a big fan alternative music,” says Steve Sanders. It’s like: Of course you weren’t, Steve. You’re the archetype average, middle class, mainstream white guy. You live on the surface of commercial American culture, nibbling whatever products the big brands feed you. In the early-90s, the transmissions that The Lips sent were too weird for guys like Steve. While The Lips tried to turn people on, their whole freaky look turned off the Steves of the world—and their whole real or imagined association with ’90s “alternative culture”—until the right mainstream sales channels could curate and sell the band to him. The right marketing made the freaks approachable, even appealing. The normals couldn’t talk to the freaks in high school. The chasm between us seemed too deep. But as alternative culture became pop culture, the ’90s jocks grew out their hair and started dressing like the freaks had years earlier. As they started buying the Nirvana records that Kurt Cobain told them not to buy, people like Steve suddenly felt okay investigating weird stuff like The Flaming Lips. He wouldn’t have liked the cover of Transmissions if he found it by himself while browsing at Tower Records. But here with his friends, placed on stage in front of him at his safe familiar diner, he gave the freaks a chance, and gee whiz, they were alright.

In the sales world, potential customers are called ‘prospects.’ Promising prospects are called qualified leads, which you try to convert into paying customers. Putting the weird band in the Peach Pit converted Steve to a consumer of the alternative music he didn’t think he liked. The record label and the TV producers captured the consumer in their path-to-purchase. And the record label got the return they wanted for their alternative band investments: a band that went from lighting things on fire in a small Oklahoma club to playing broadcast TV. The labels won. They turned weirdness into cultural capital that even a regular guy could comfortably consume and then use as a badge of his own coolness, since he had briefly walked on the wild side and returned with this souvenir that he could wave around as proof that he belonged to the group. Because ultimately, he was still buying acceptance into a group, not true individuality or rebellion. Not that authentic individuality mattered. That wasn’t the product. The feeling of coolness was the product, and Steve finally got it. Acceptance is what most teens want anyway. It’s only natural.

The less cynical piece of this puzzle is that, while everything is for sale, the jelly song itself was objectively good, and music is something whose power can exist outside of—or at least withstand—corrosive capitalist forces. You can sell great songs to death, but they still manage to move people, and that’s what music is really about. That’s why this unnecessarily long essay you’re reading matters, because this weird jelly song was just fun to sing. It made you laugh, and laughing was as spiritually nourishing as singing. It didn’t matter who sang. In fact, the more people it got singing together the better. Steve’s friends and my freak friends needed a middle ground, a common point of connection, and if we could all share this moment together—and even sing and dance at a show together—that felt like social progress to me. ’90s kids could be so protective of their bands: These are our cool bands, and those are yours. Don’t ruin mine! Ultimately, it didn’t matter if the straight world of jocks and suburban mall rats now knew The Lips. In fact, all the better: Maybe The Lips’ popularity could get more people to look kindly on the freaks and help tear down the walls that made regular folks more accepting of oddity in general. Even if the Steves went back to being close-minded shitheads who made fun of how you looked or tried to punch you in the mosh pit at rock shows, we’d always have this moment united by music.

As expected, the 1995 episode further propelled the lysergic Oklahomans to fame. Once they crossed into mainstream culture, they never went back to arty obscurity. I was certainly hooked.

Looking back, Transmissions was the sound of a more refined, professional group with more money for studio time than they’d ever had, but they were still freaks. Think of the lyrics Coyne sang to venues full of kids: “My brother’s at the morgue / He gets up off the floor / He contemplates his escape …And he calls up the insects he commands / And the waterbugs attack the policeman.” How many kids could relate to that? Or even sing along? It didn’t matter. The band was never the same.

As a hot commodity trying to get their weird music heard, they played as openers on tours with Tool, Stone Temple Pilots, and Soup Dragons, then got invited to open for Candelbox—a horrible Grunge copycat band—with money too good to pass up. The Lips didn’t sound like any of these bands, but under the marketing rubric of alternative music, these pairings make sense. These were also all rock bands in the standard early-90s mold: bass, drums, lead guitar, rhythm guitar. During Ronald Jones’ time with The Lips, they were a guitar-band, even though the lyrics ranged from simple requests to trade brains to stories of sitting around watching a friend’s invisible dog. Don’t get me wrong. Jones’ tenure is my favorite Lips era, but during those years, the world was drowning in loud guitar bands, so with their long hair and beat up Stratocasters and Fenders, The Lips didn’t break the mold visually—not until you heard them. Then you went Whoa.

In the alternative era, they actually offered something alternative.

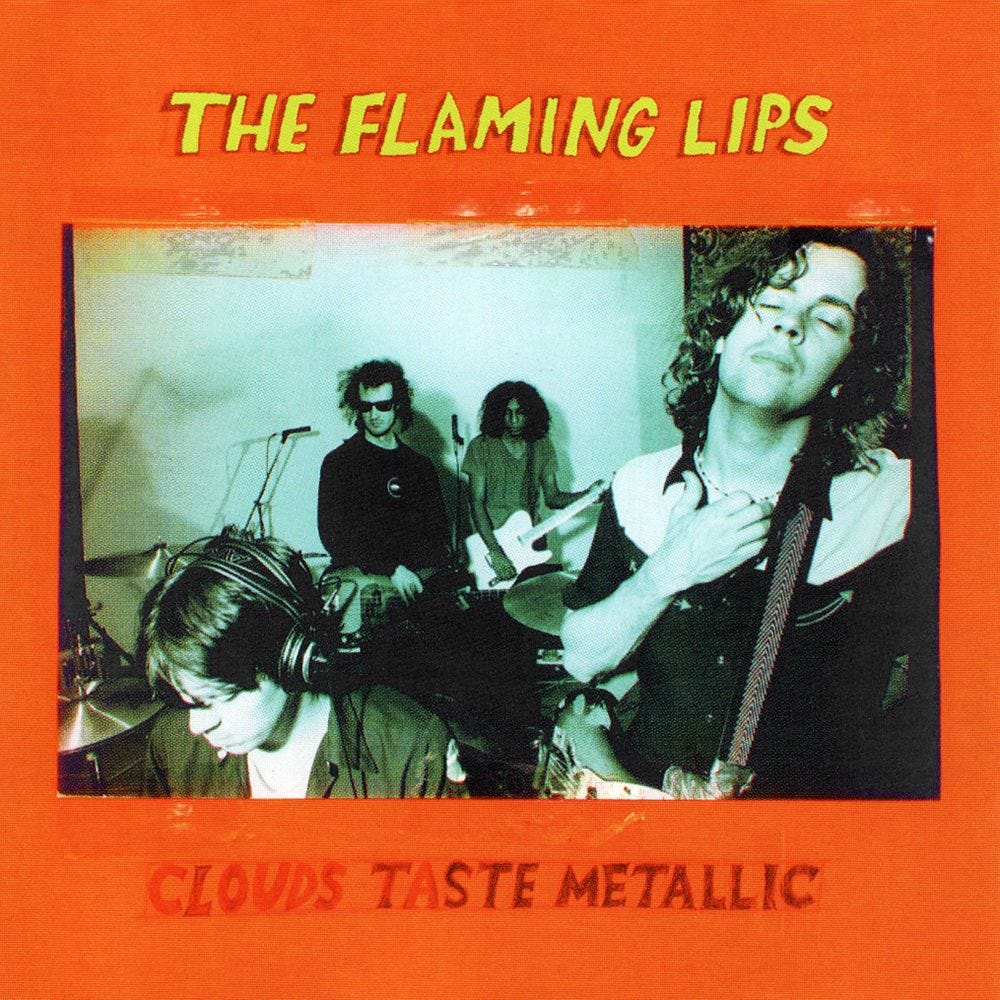

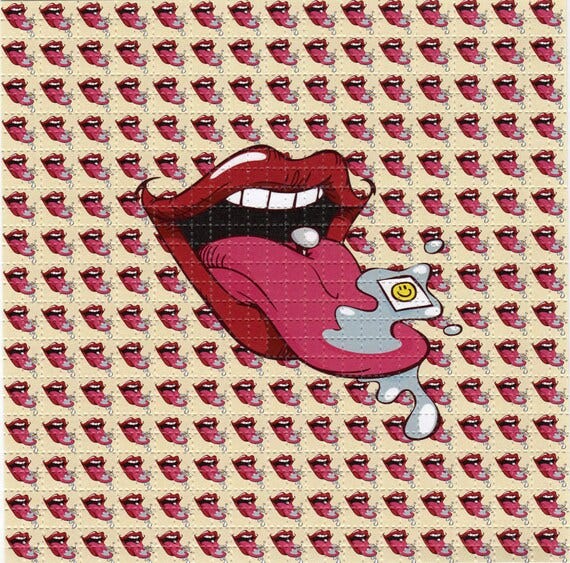

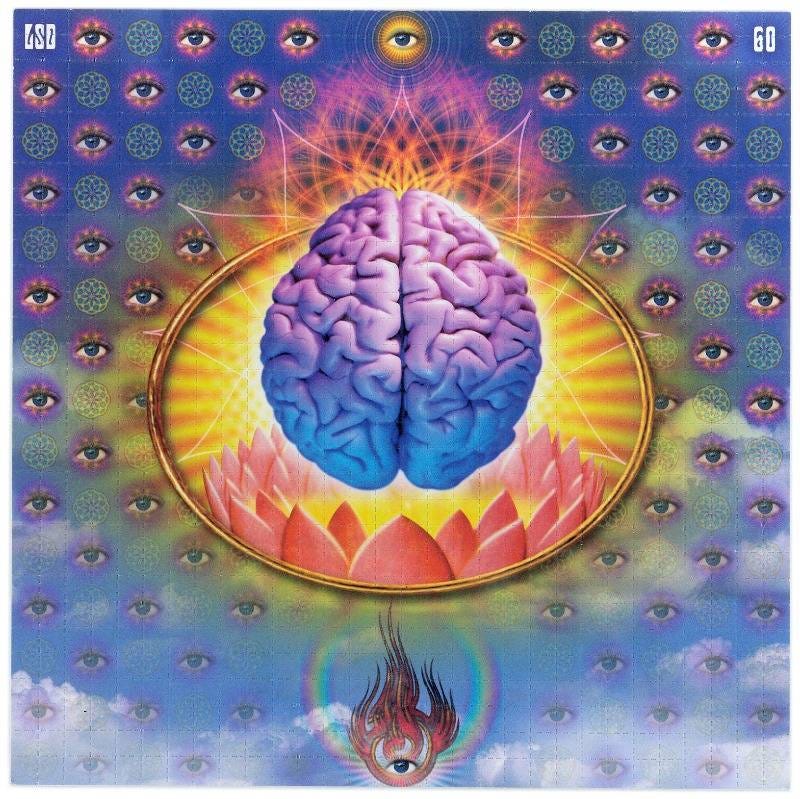

After “Jelly,” many people assumed The Lips were another one-hit-wonder in an era of one-hit wonders like Stereo MCs’ “Connected” and Toadie’s “Possum Kingdom.” But The Lips felt confident they could make more great music. In 1995, in the middle of the “She Don’t Use Jelly” era, they released their anticipated follow up album Clouds Taste Metallic. Tabs of acid tasted metallic, and my friends and I took enough psychedelics to get the reference. While Transmissions still ruled me, Clouds added power to the mix. Turning on to the Lips at that moment meant getting dosed with a double-whammy of lysergic music along with actual doses of acid. It was awesome.

It also inspired me. I needed inspiration.

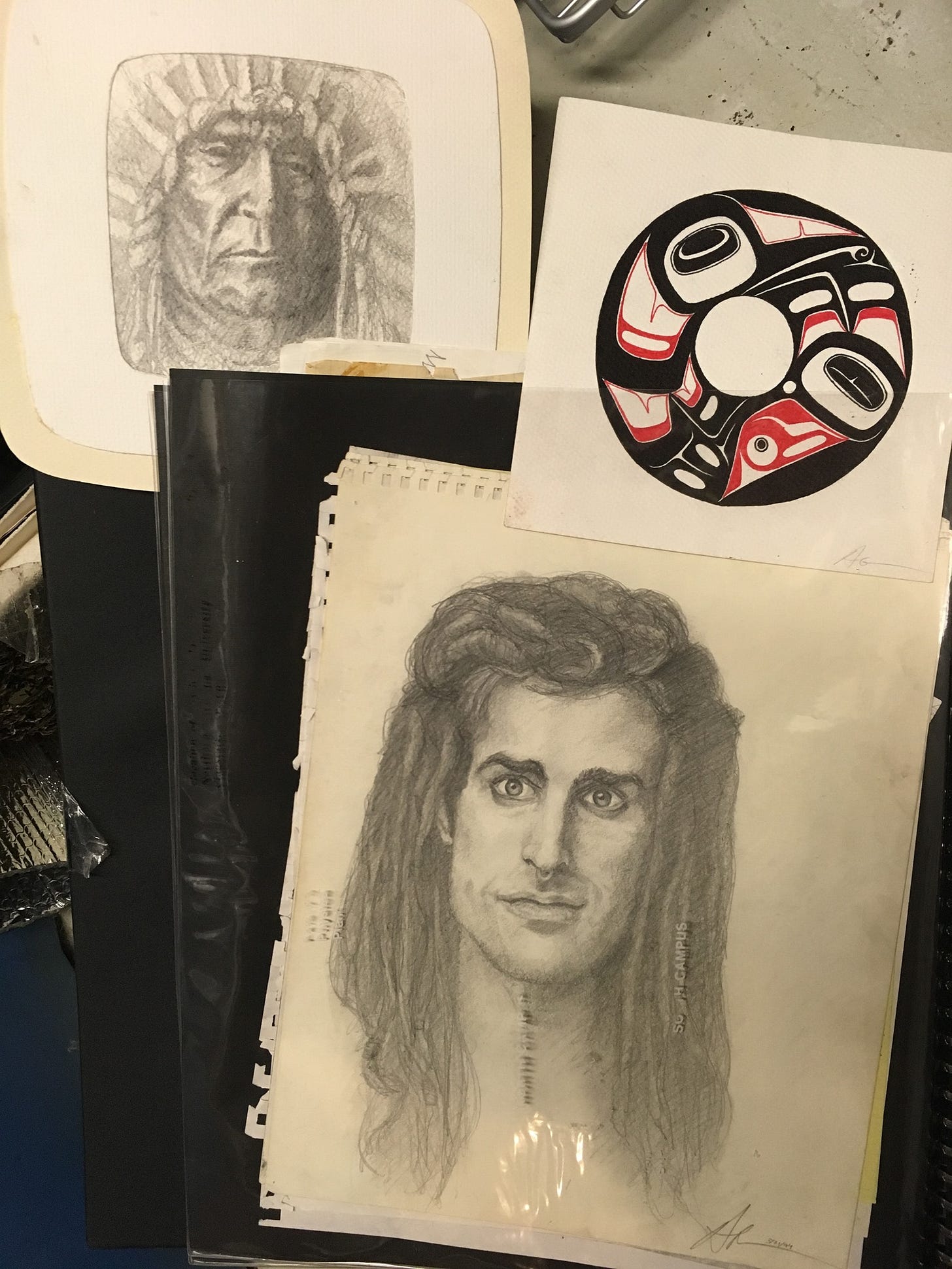

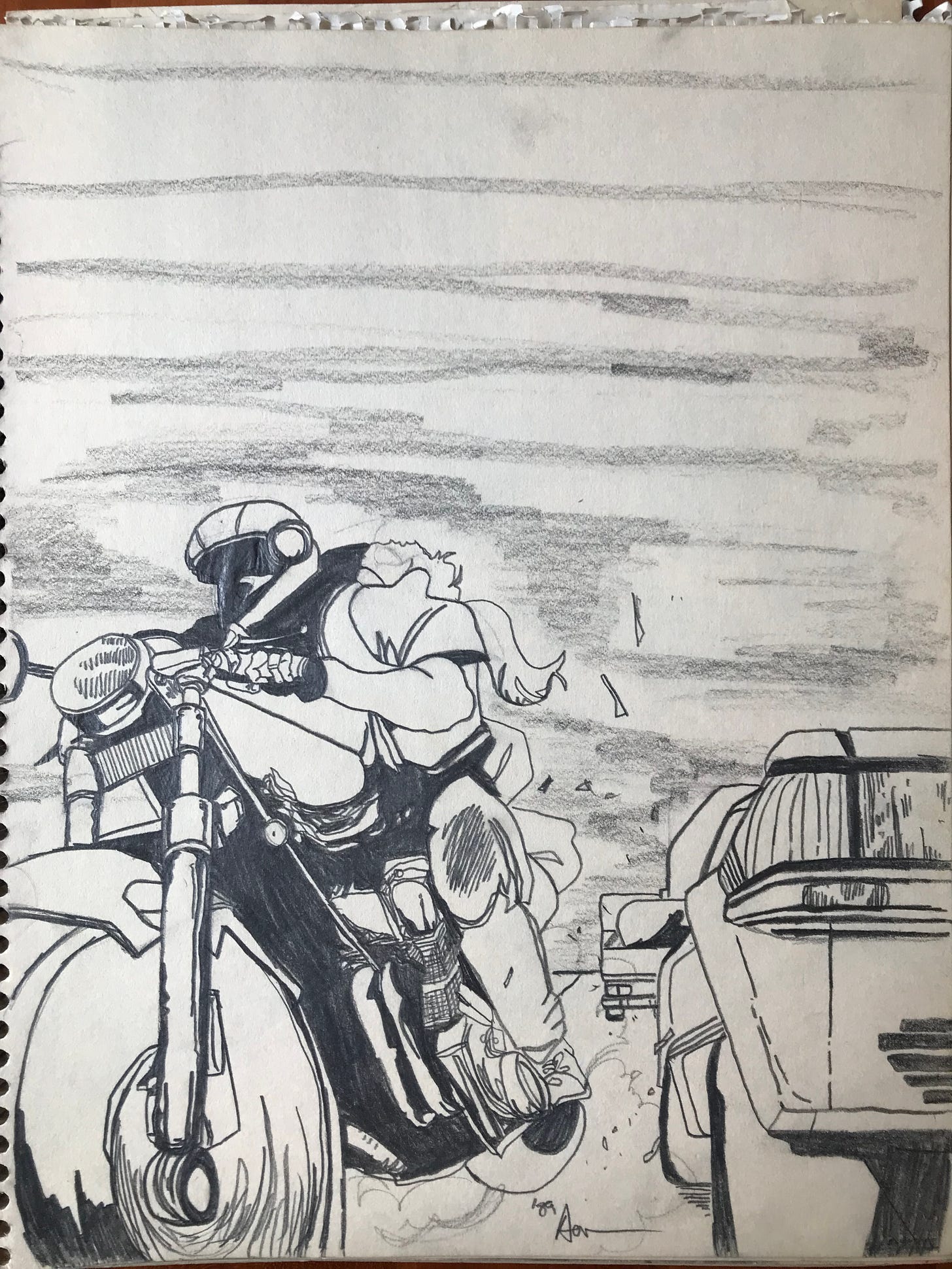

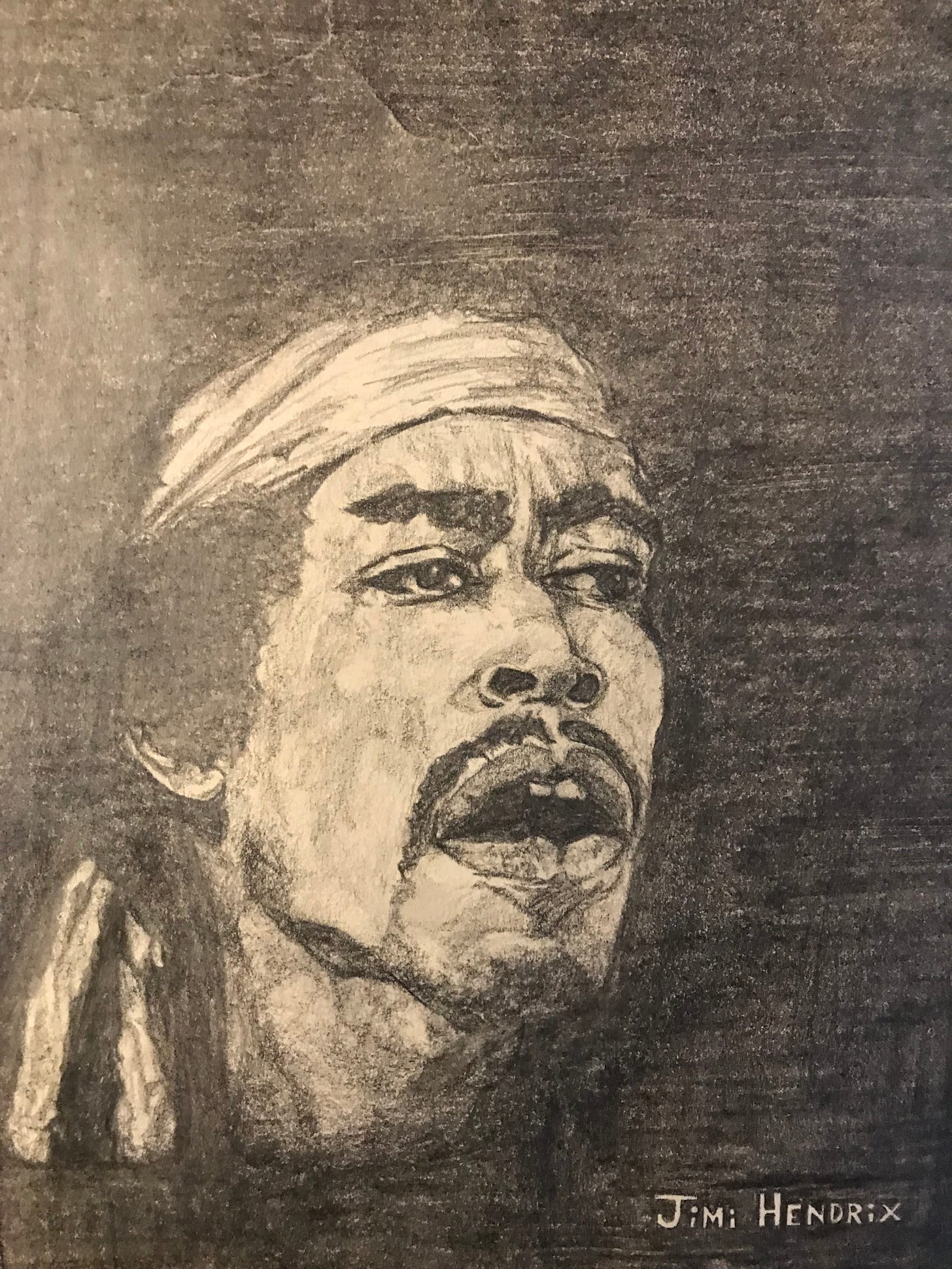

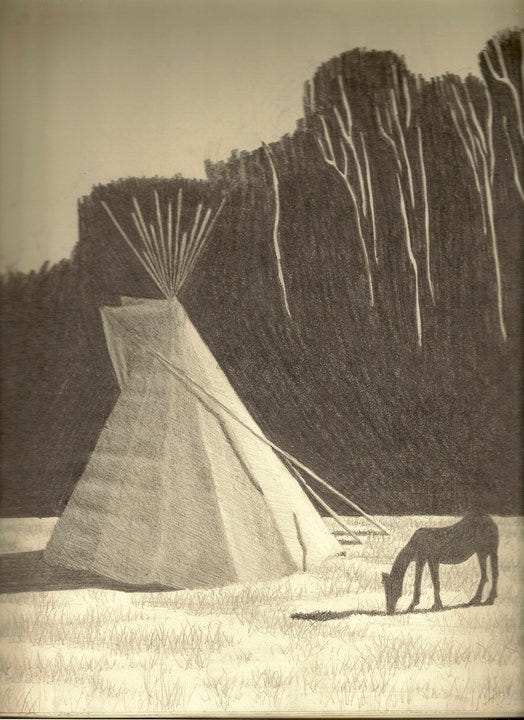

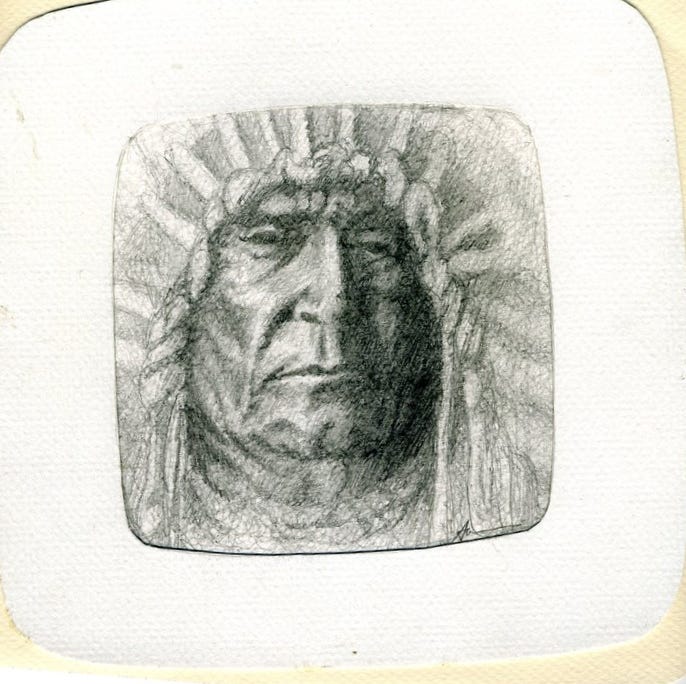

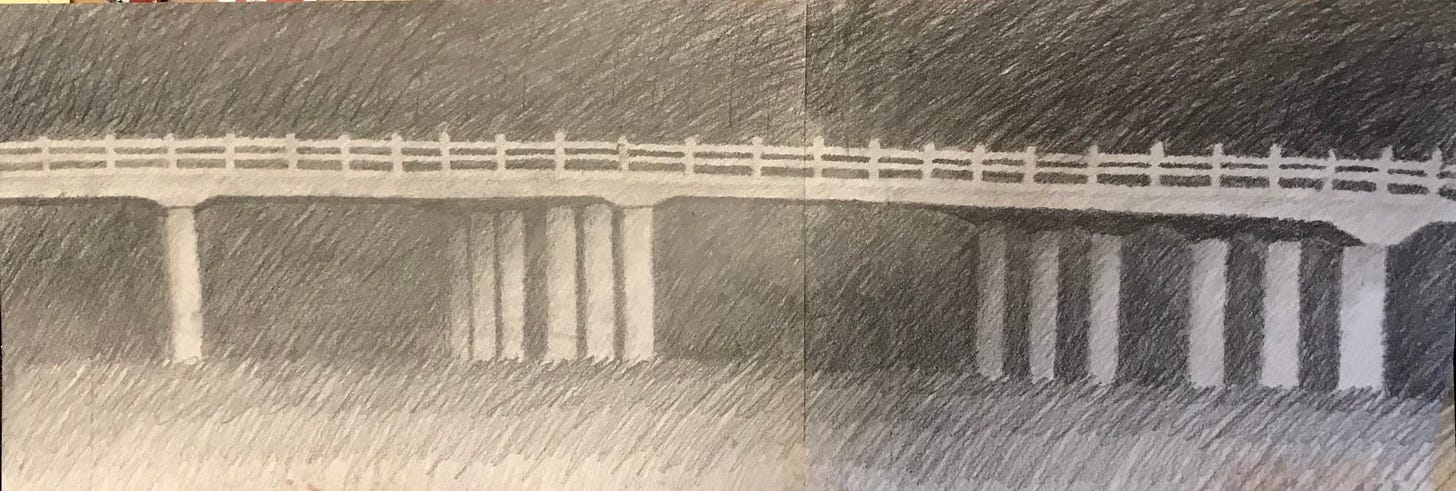

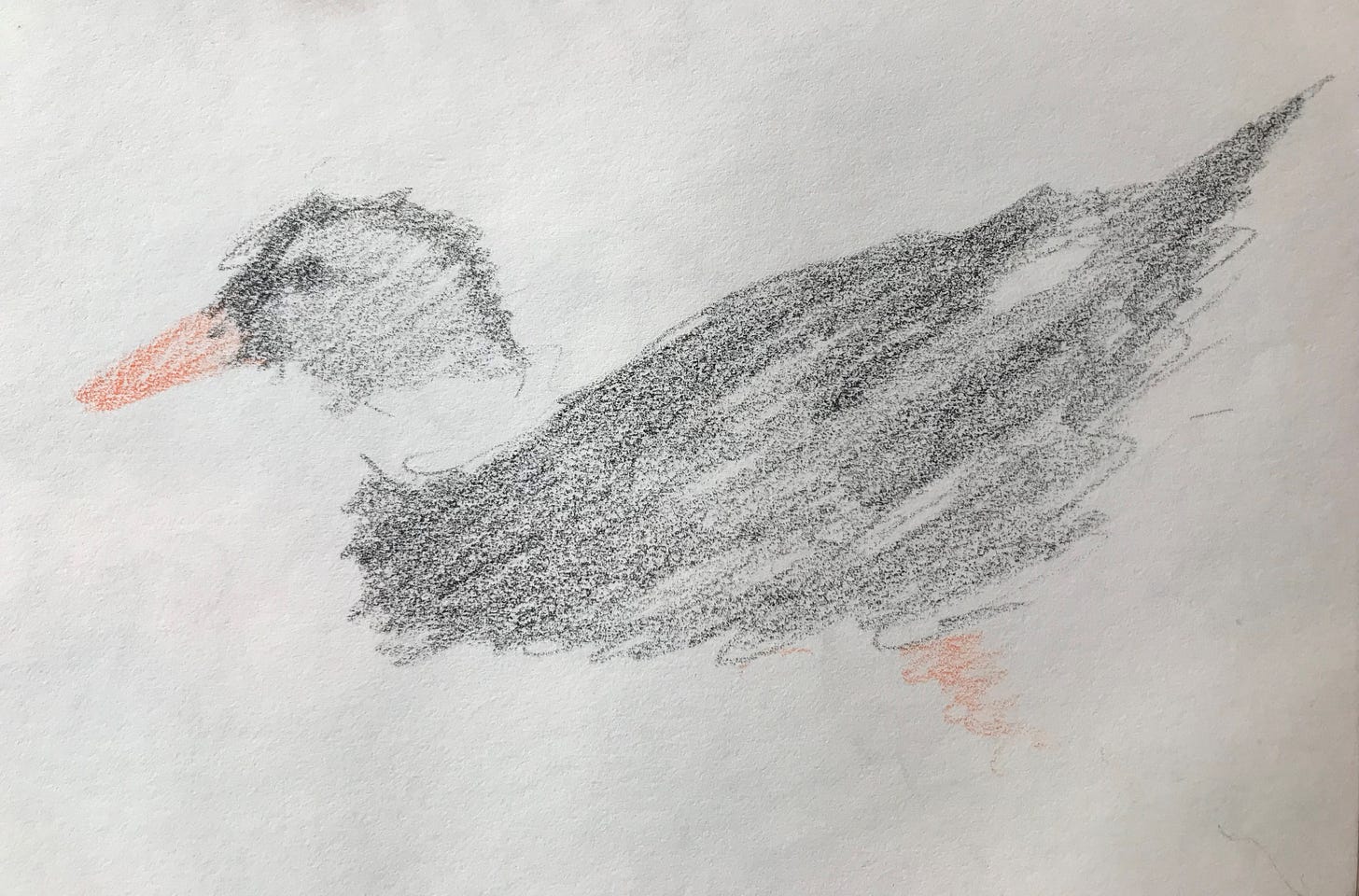

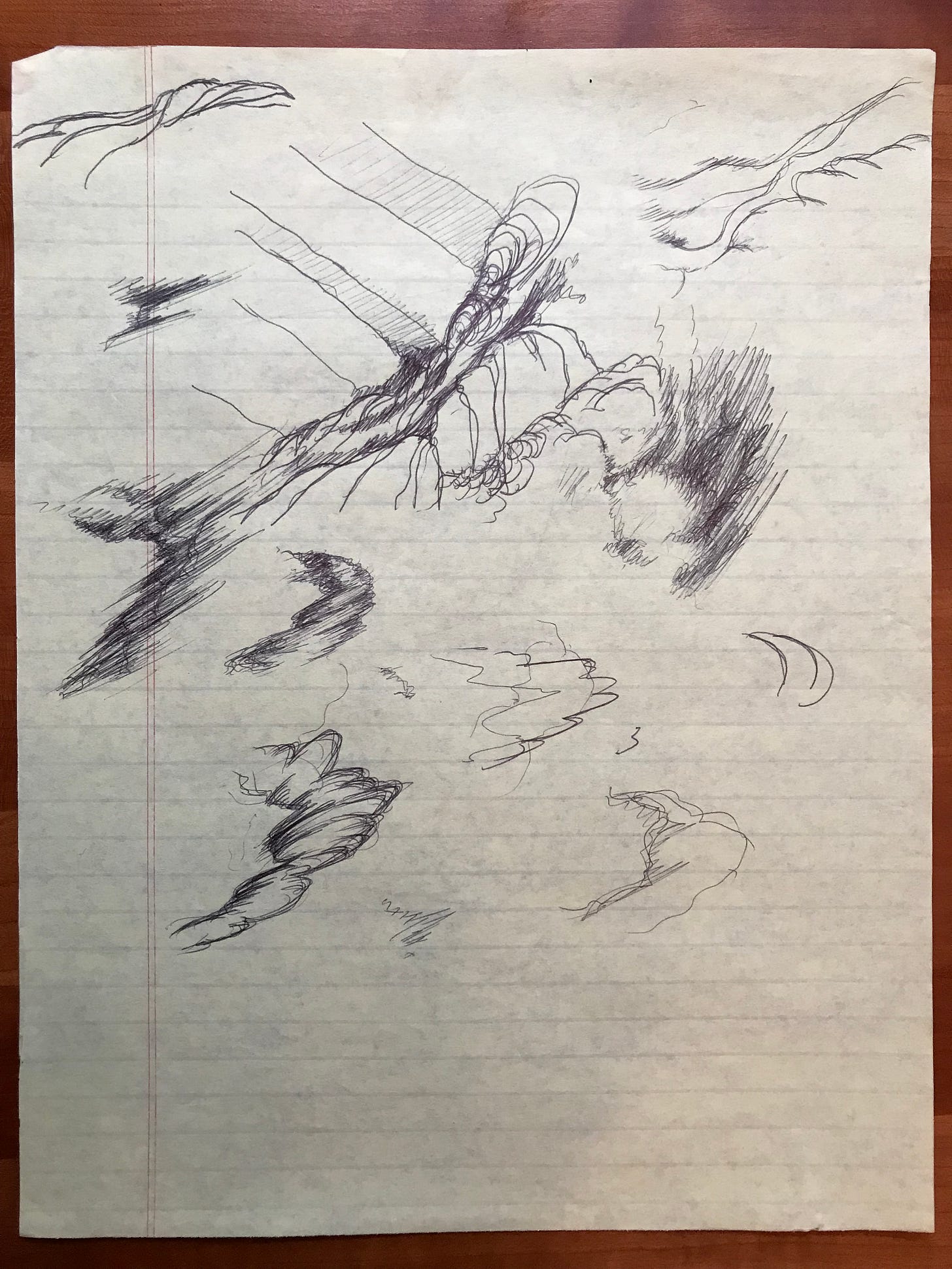

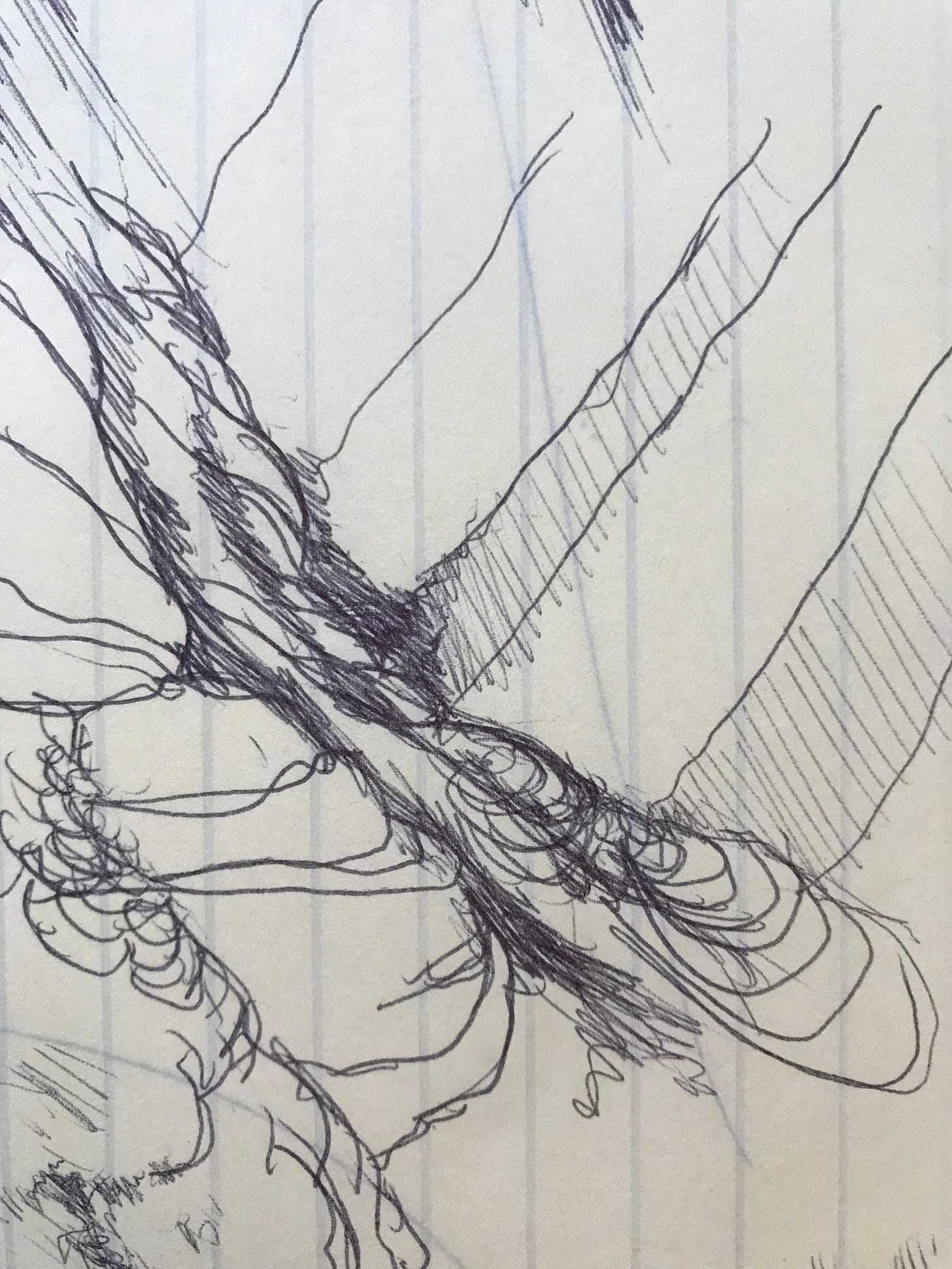

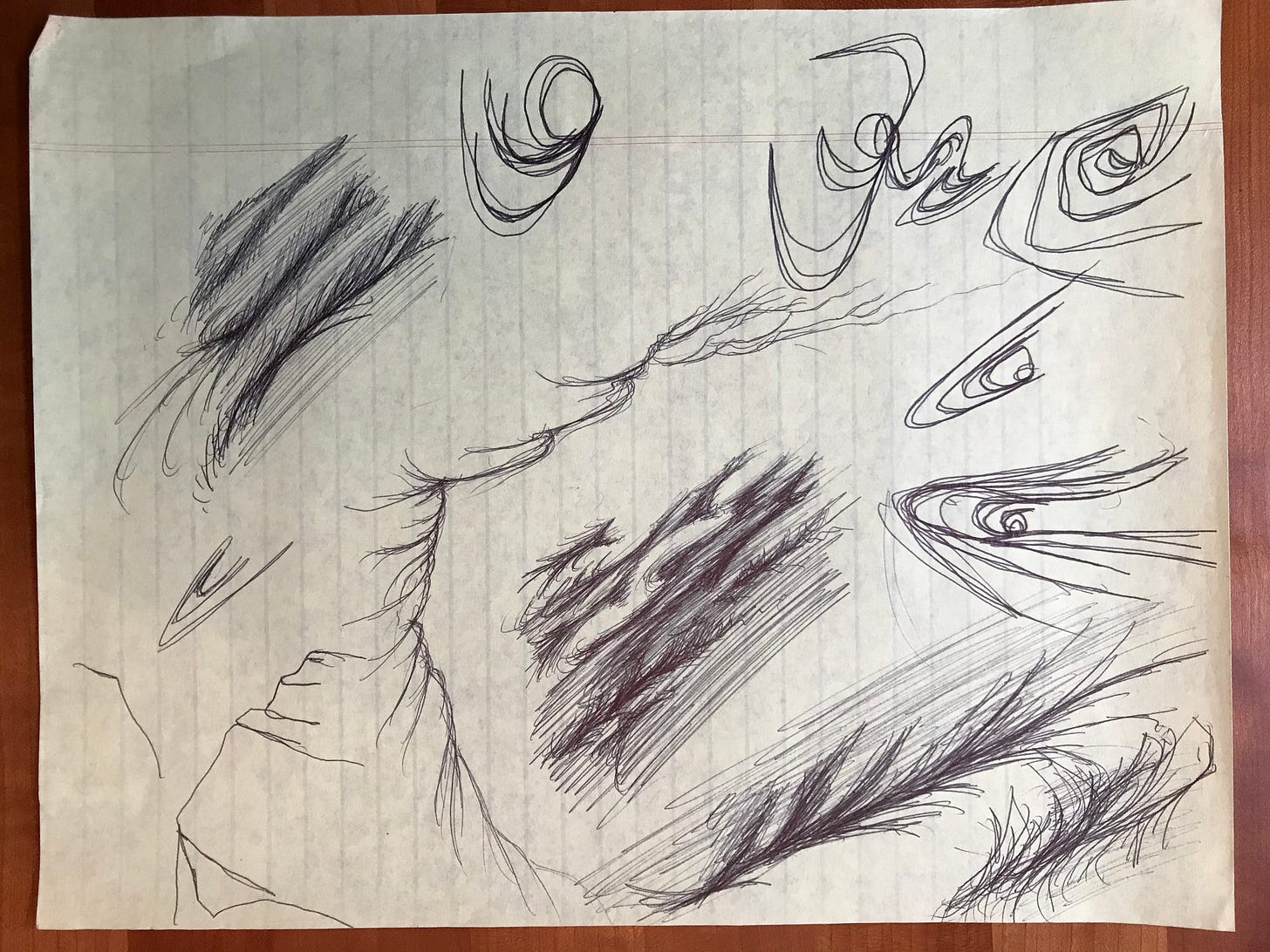

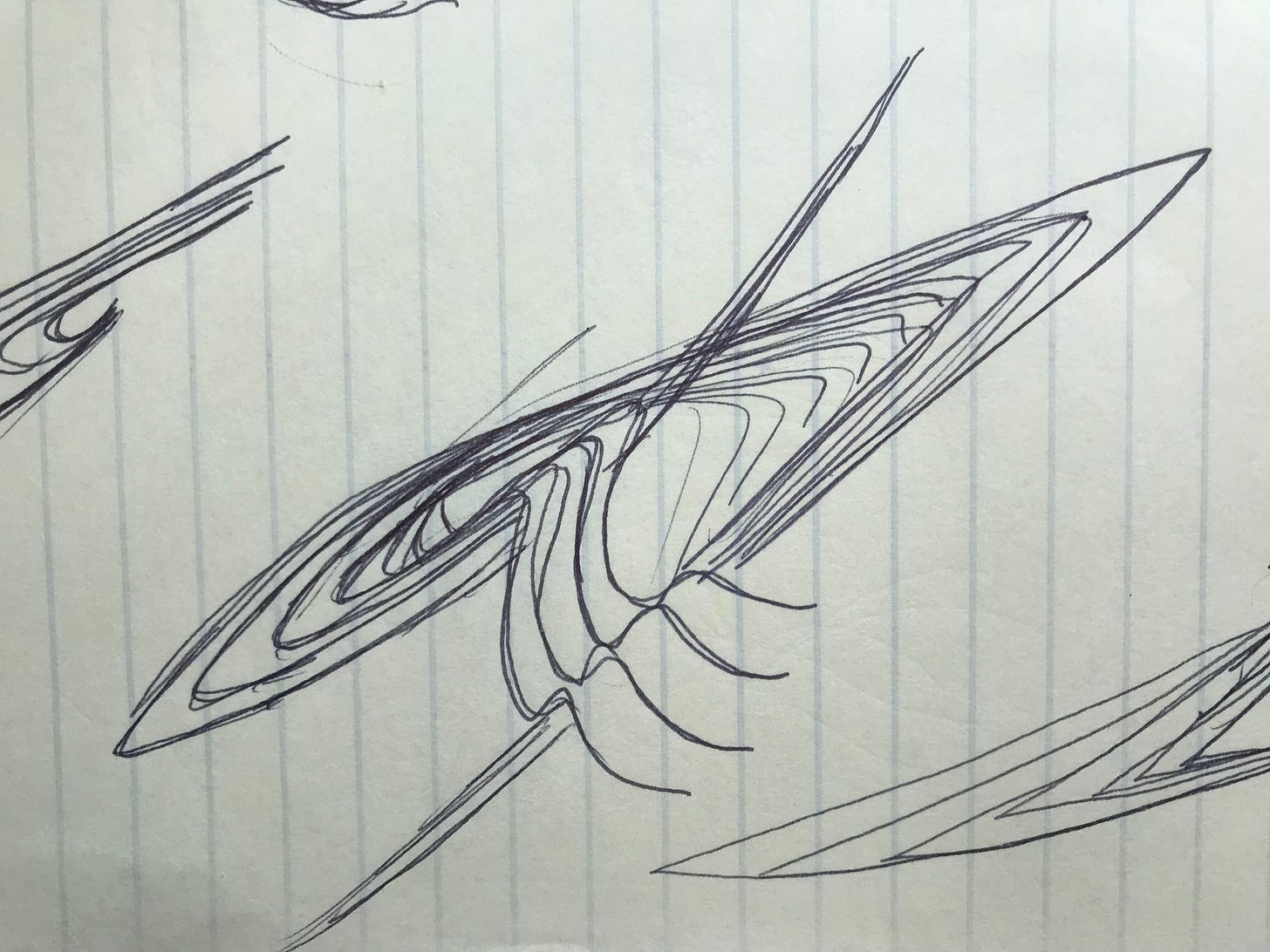

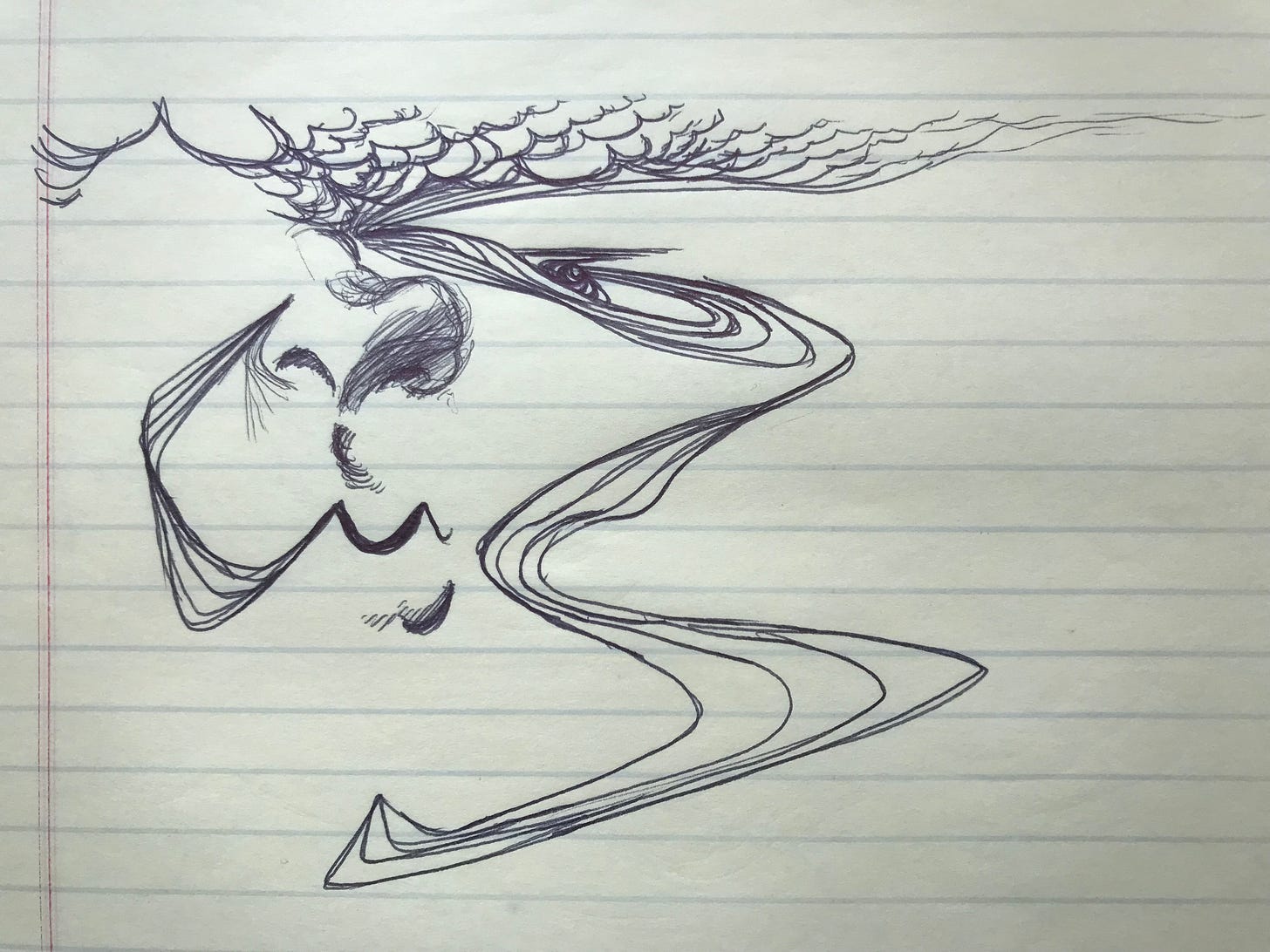

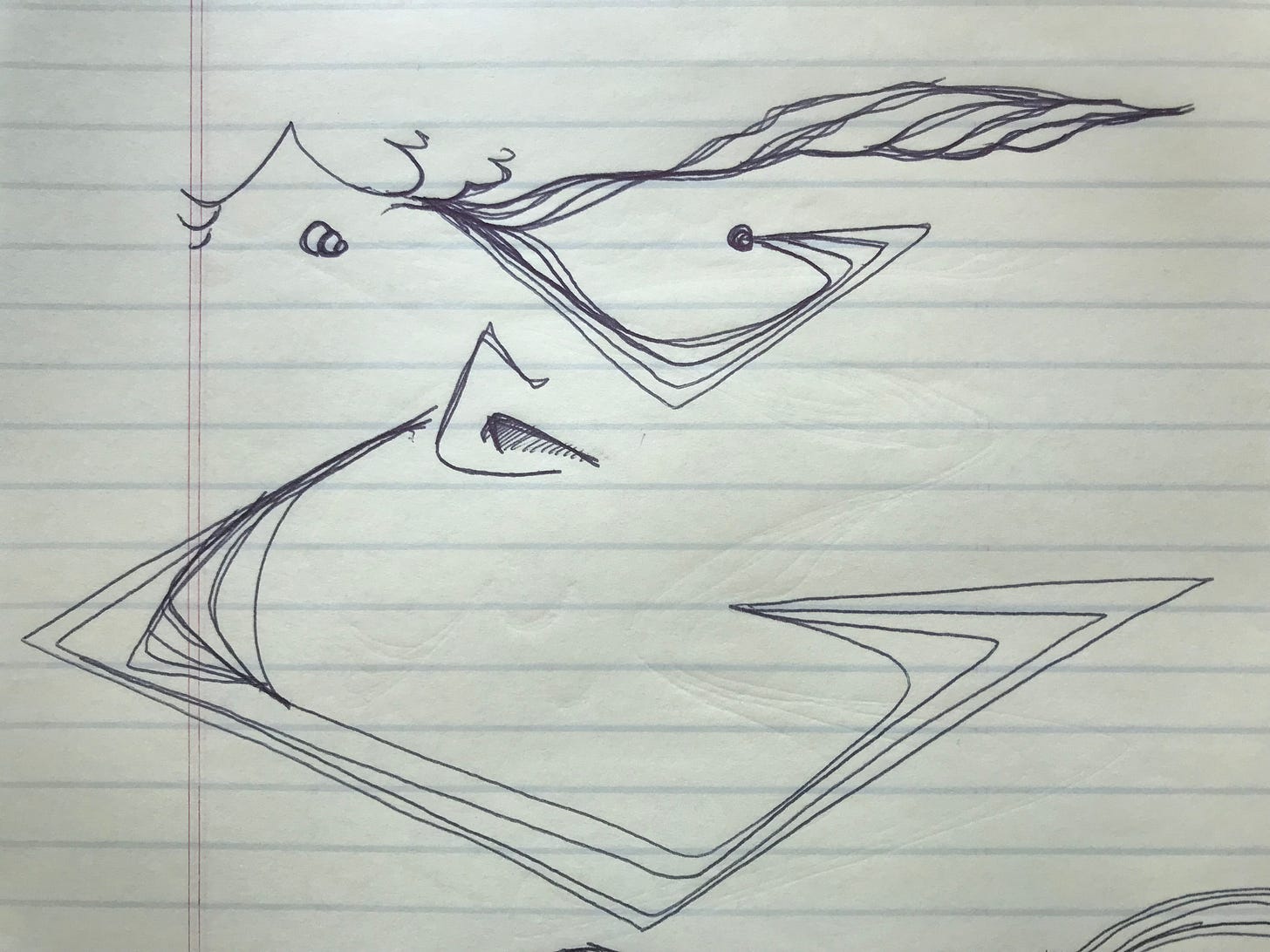

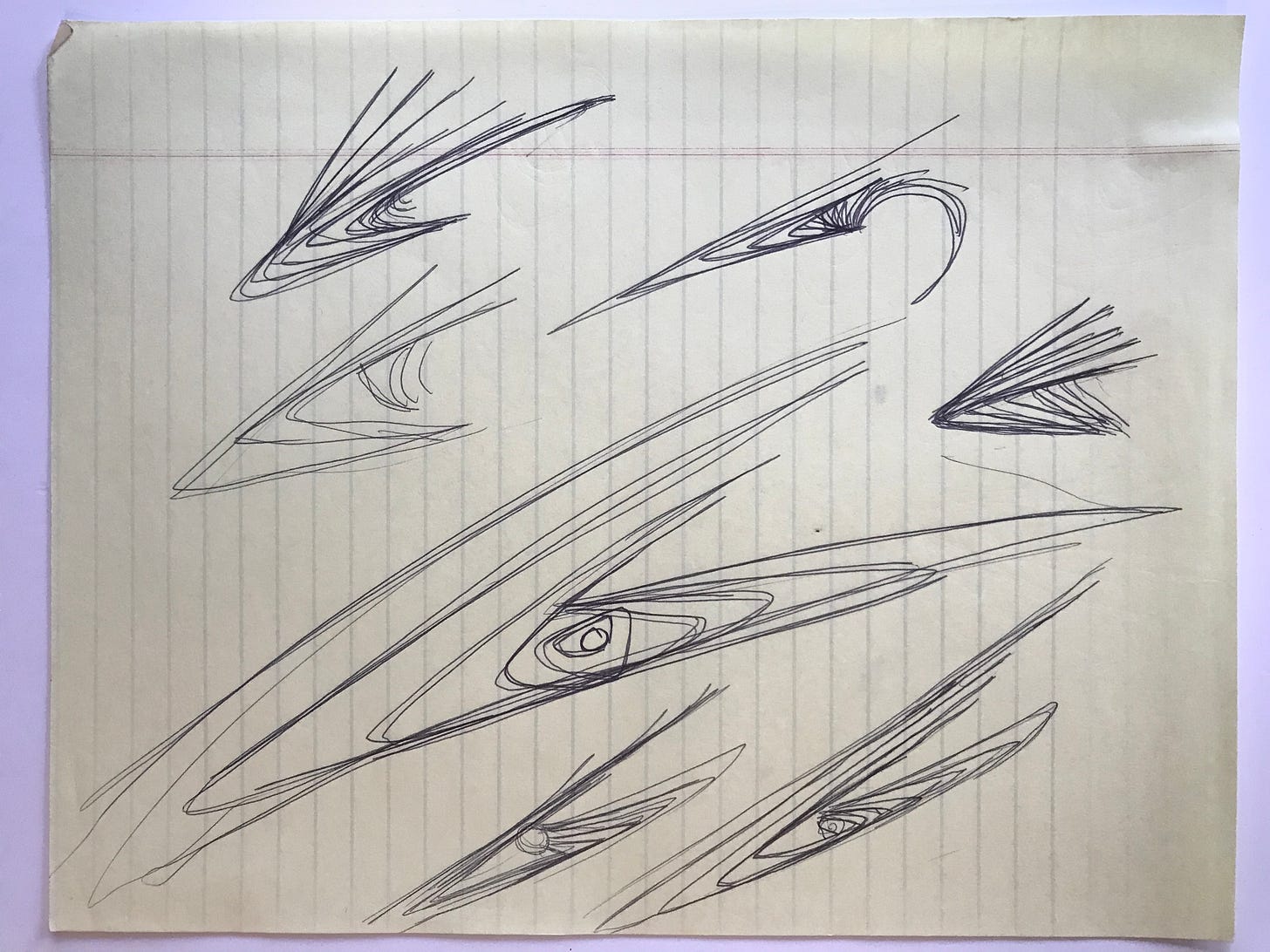

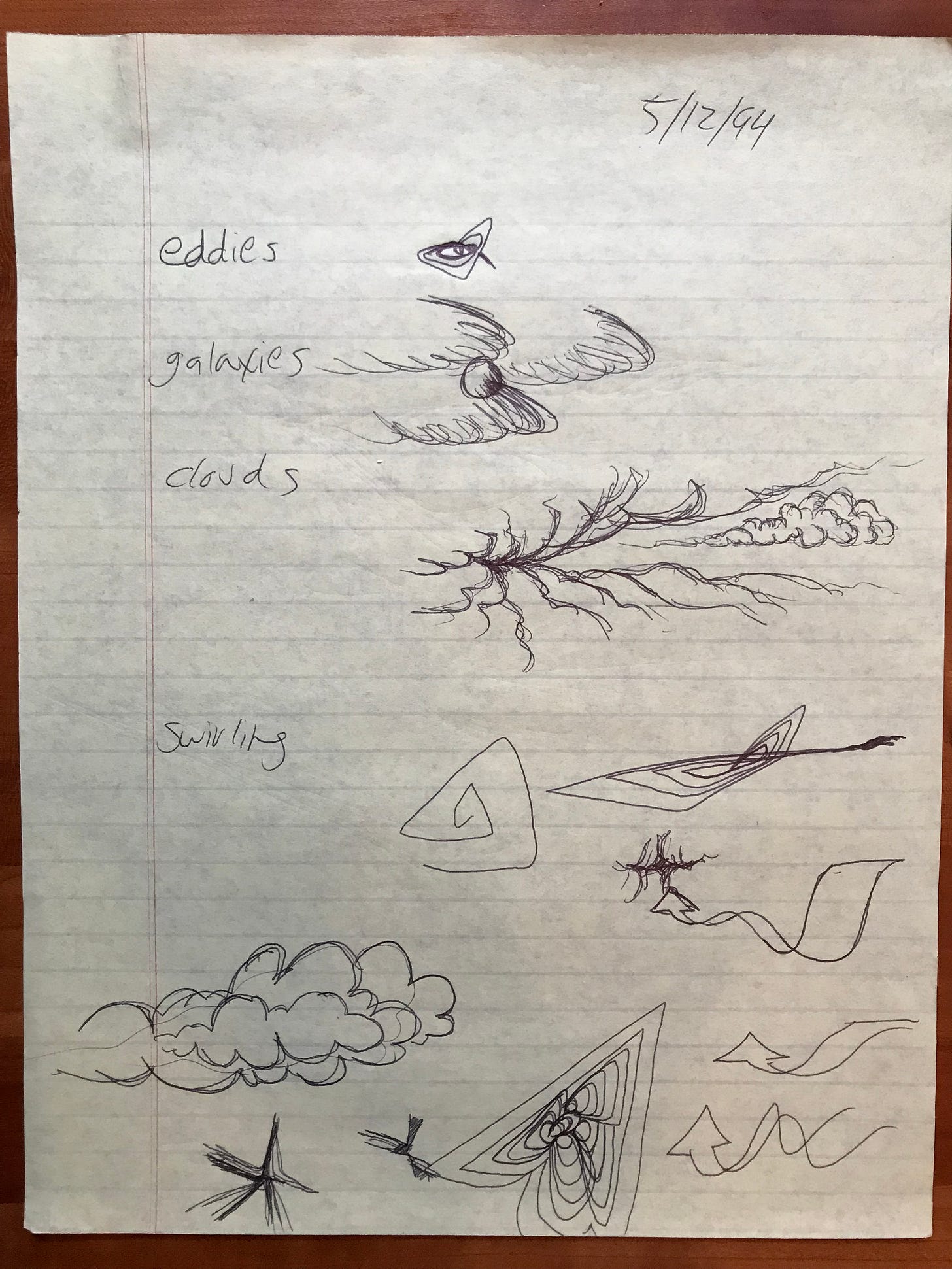

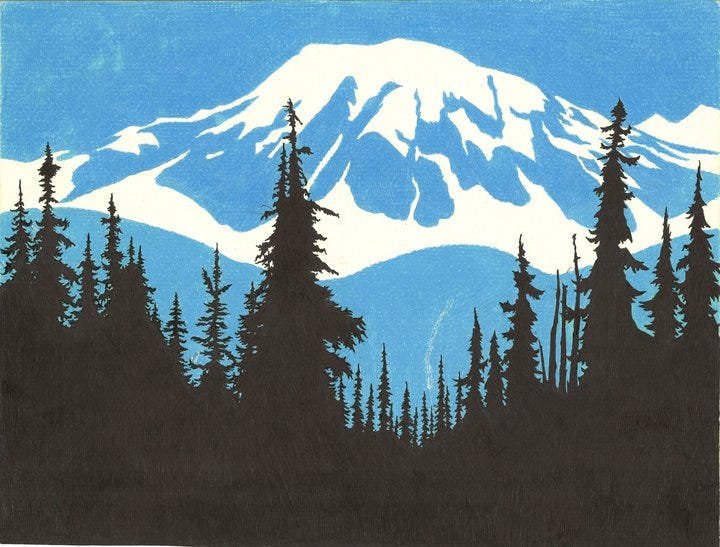

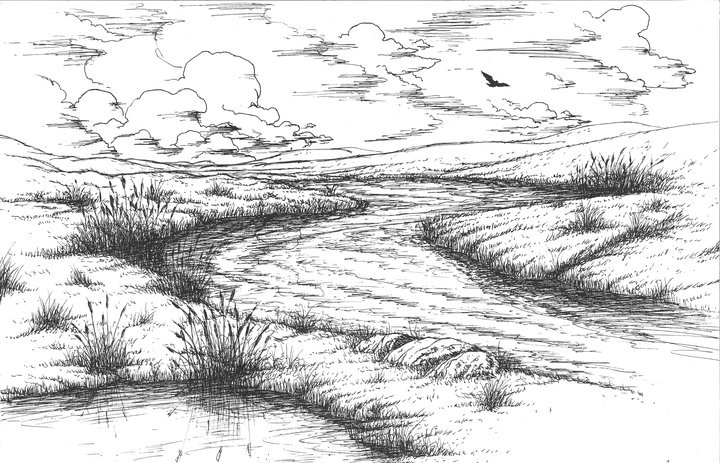

For most of my life, I’d been the stereotypical drawing kid, the one hunched over a piece of paper, engrossed in some vision. I drew alone in my bedroom at night. I drew on paper placemats at restaurants while the adults talked. I drew on napkins and instruction manuals and doctor’s slips and in my notebook during class. Lack of proper materials never stopped me. I just found a napkin and a cheap Bic pen. Whatever was around became my medium. I could draw everything from abstract geometries to landscapes, and I eventually drew hard faces from Edward Curtis photos and portraits of Jimi Hendrix and Jane’s Addiction’s singer whose likeness impressed people and surprised me. People knew me as the drawing guy. But drawing had started to feel constrained, like I needed a more robust medium to express the intense combination of ideas, images, feelings, and stories inside me. As a sensitive cerebral teen, I felt all these powerful things that, as an artistic person, I felt the urge to do something with. The creative impulse was wired in me, but I didn’t have the discipline or direction to seriously test new modes of expression. The Flaming Lips somehow connected with the part of me that the psychedelic mushrooms had already activated, and the combination opened something further, showing me the swirling, terrifying range of possibility, not just in art, but in life.

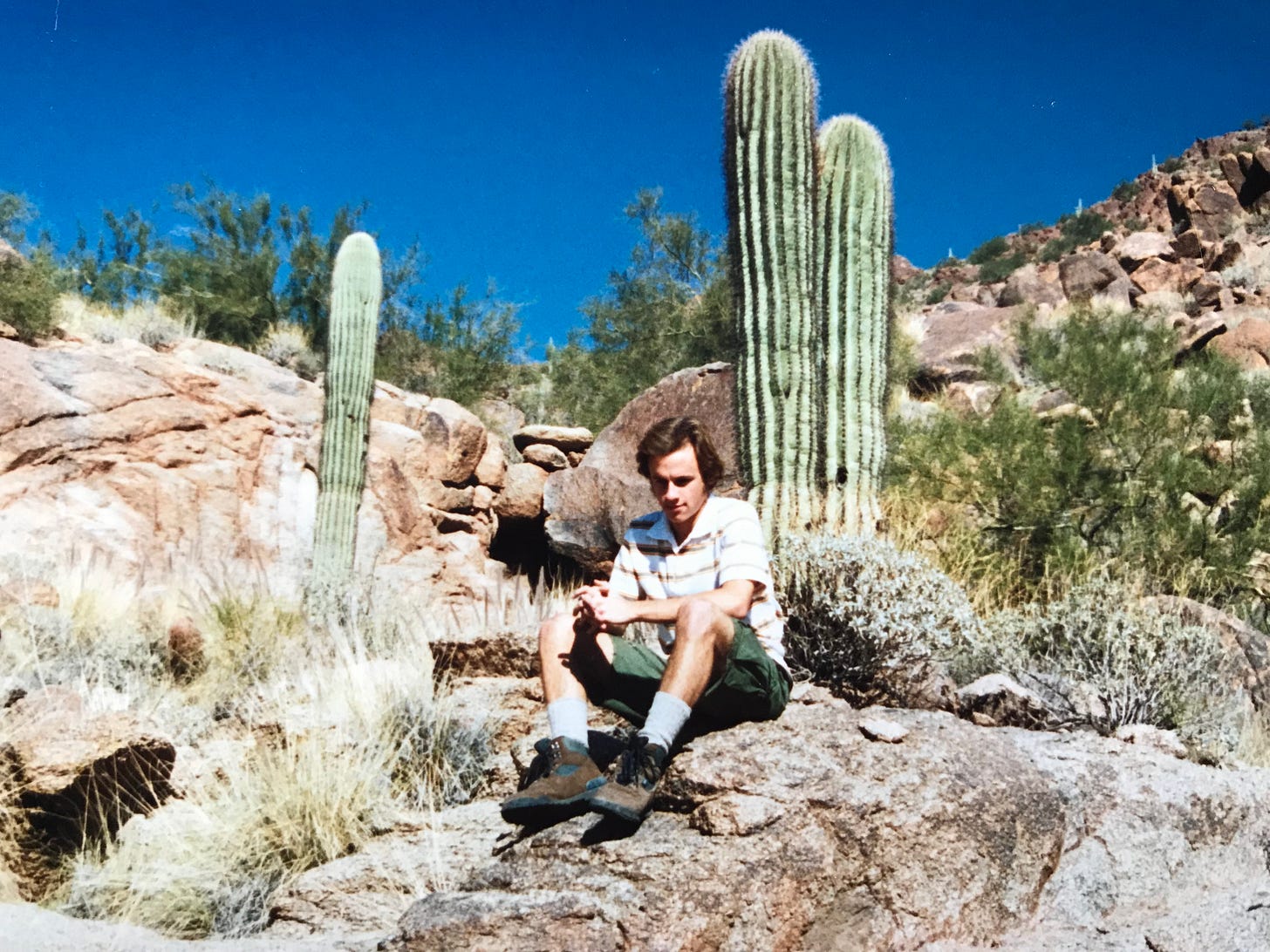

You could live your life in infinite ways. A 9-5 office job wasn’t for me. And why stop at drawing? Why not try music, photography, and writing? Why not live in a van and just travel the American West?

“So many people have good ideas, but they don’t do them,” Coyne said in the band biography Staring at Sound. “A mediocre guy who works all the time gets more done than the super genius who hides in his glass castle. You gotta do stuff; you can’t just sit around and think about it.” Even the title of The Lips’ biography referenced the synesthesia that embodied their inability to be constrained by space, time, or genre. Naturally, the book borrowed the title from a song.

Although Clouds didn’t perform as well commercially as Transmissions, who cares? Clouds is an absolute classic Lips album, and one of the best of that decade.

“When we hit Transmissions and it blew up and sold a whole bunch of records, and we had ‘a hit,’” Ivins told Pitchfork, “we thought ‘Alright, now we’re in.’ And then we put out Clouds Taste Metallic and it went right back to however many records we sold before.”

Not enough apparently. The band kept expecting Warner to drop them, so they decided to lay as low as possible.

As the Lips’ manager Scott Booker told Pitchfork: In 1995, selling 36,000 records was considered a failure. But somehow, the goofy song about nonsense endures. “Jelly” is still catchy. It’s still funny. And new listeners keep discovering it—like my daughter. Maybe playing it for her now will create a nostalgic childhood connection later, a song from a decade she never knew.

Contrary to their lyrics, The Lips’ bad days didn’t end. In 1996, a year after Clouds came out, Ronald Jones left the band even more suddenly than he’d joined it. No one truly knows why he left or where he went after leaving. “That part of it, I think, is still kind of a mystery, even to us,” Coyne told The Oklahoman. “Until we know, I think the mystery is the thing.” No new photographs of Jones have surfaced since 1996, and he’s never done an interview. He literally disappeared himself from the face of the earth and spent the subsequent decades somewhere in Oklahoma. Maybe one day he’ll surface, but the story of his departure and existence remain one of the enduring mysteries of rock ‘n’ roll.

During the time I jammed Transmissions and Clouds, it didn’t seem like we fans were witnessing profound creativity from a singular guitarist on the cusp of disappearing. This didn’t seem like some golden era of a band that would be mythologized years later. Jones was just another cool dude wailing on guitar with long hair draped over his face, and like everything else in your young life, it seemed like things would always be this way. Time passed. Things sucked. Days felt the same. Things were forever. Forever would feel like this. As the ’90s passed, they passed slowly enough that nothing suggested these years would eventually resemble some of the best in my life, or that the world wouldn’t always look this way, with The Lips yelling “Vaaaaaasaline!” with orange hair on TV.

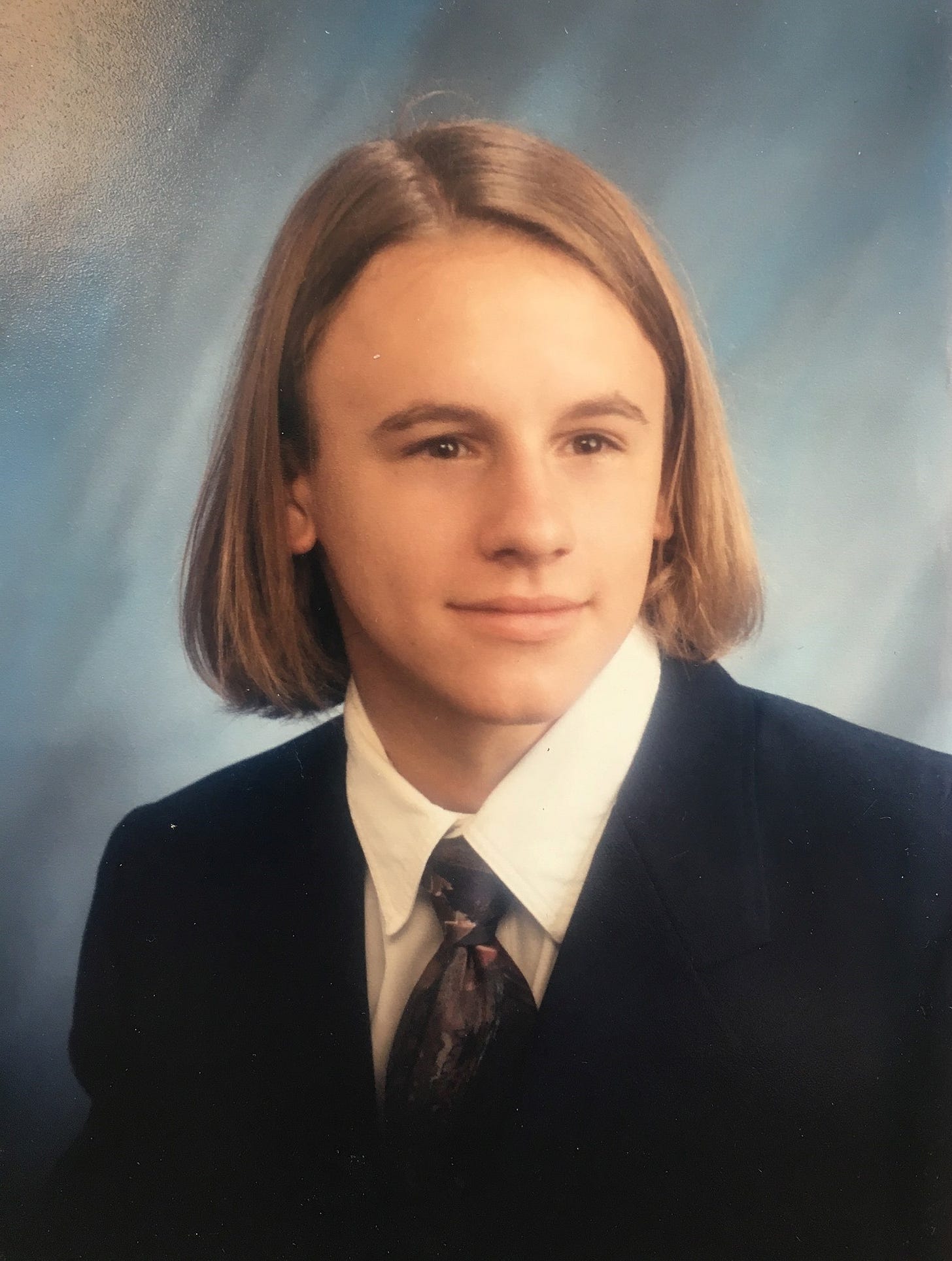

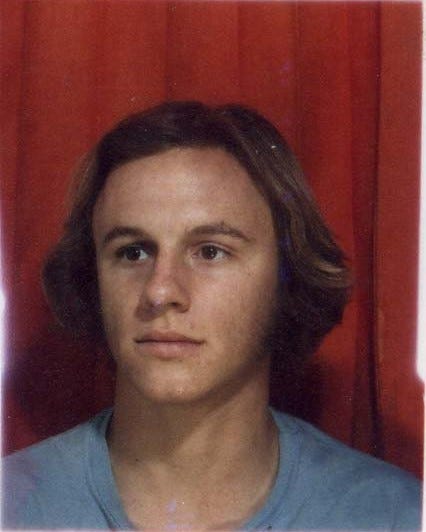

While The Lips started touring in support of Transmissions in the summer of ’93, I was getting ready to start college.

The last year of high school can involve a lot of prep: meetings with college counselors, talks about majors, AP classes for college credit. The U.S. College Board created the Advanced Placement program to challenge high school students with college-level curricula and send prospective universities a strong message: This student is serious about their education. I was smart. I liked intellectual activity, but I wasn’t serious about anything other than my friendships, my drawing, and rock ‘n’ roll. I didn’t take AP classes or fret about transcripts. I worked hard in classes that I liked, and I passed classes I disliked. That set the mode for the rest of my life: Excel at things that excited me, endure boring requirements. It’s been a problematic approach.

My mom was always telling me I had to do something extracurricular in high school: band, newspaper, a club, anything. So I wrote an untitled poem called “A Poem” for my all-boy school’s annual art journal. “Society may think one way,” I wrote, “But to society’s dismay / They can’t make me something by their decree / Only I determine who I should be.” Clearly I’d never written poetry before. It was my first published piece of writing. I briefly volunteered in the school newspaper, but it didn’t click. I preferred the excitement and vernacular of rock music and skateboarding to the little subterranean high school office where newspaper staff wrote articles about campus life. The idea that I should do stuff like this instead of what felt natural to me ignited my ire. That’s why the theme of my untitled poem was the theme of my life itself: independence, rebellion, keeping the world from stifling my individuality. “Only I determine who I should be / This is so, so let it be… I’m very pleased with me.” Um, I guess I planned to fly free forever because no one was supposed to tell me what to do? I never published poetry again.

Even if the high school experience mattered less to me than my social life, I was lucky that I loved that high school age and really ate it up. While many sporty meatheads peaked in high school and would never feel as relevant again, high school was traumatic for other kids. They were trapped in small towns, trapped by parental oversight, strangled by provincialism, low expectations, and outright harassment. In college, kids could escape their smothering social circles, escape racist hicks and violent jocks, escape their past and the unforgiving pigeonholes locals put them in. When no one knew who you’d been back home, people could see you as you were now, and you could become who you wanted to be. Like heading to California, college offered the chance for rebirth. Many kids were stoked to get their own dorm room far from home. For them, college felt like growing up. My classmates sent their transcripts to their top choices, hoping they’d scored well enough to get into their favorite school. High school friends got accepted to places like Harvey Mudd and Pomona. Many of my closest friends didn’t go to college. They worked, joined the Navy, and got their GEDs. I didn’t fret about transcripts or have favorite schools. My parents couldn’t afford to send me away, so I went to the state school a few miles down the street.

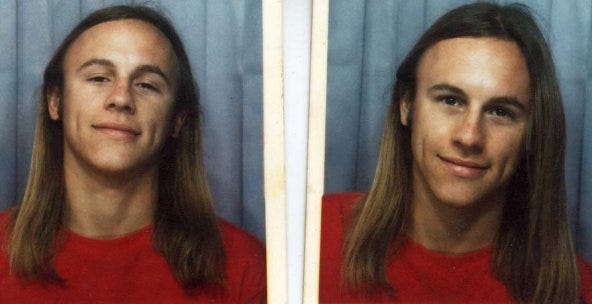

Arizona State University was a great affordable university with a rich history, and it was good enough for us. Even if my parents could have afforded out-of-state tuition, I wouldn’t have gone. That wasn’t my fantasy. I didn’t mythologize Brandeis or come from an Ivy League family who wore Yale sweaters and needed me to uphold tradition. My mom graduated from ASU. My dad started ASU and didn’t finish because of parental responsibilities. They both stressed the importance of education, but they didn’t fixate on universities’ status. The only universities that appealed to me were by the beach—UCSB on the Santa Barbara coast and the University of California San Diego, and that was only because Southern California was the center of the universe. Since we couldn’t afford oceanside schools, I was fine with whatever. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with myself, but I knew I didn’t want to leave my best friends, so I kept doing what we were already doing, which was partying, camping, and studying. Phoenix sucked, but my friends made it livable. Sure, college sounded fun. I was excited to learn new things and have coed classes where I could actually talk to real live young women, but I was mostly excited to get out of a Jesuit high school that wouldn’t let students grow their hair past their shirt collars. And I was excited to wear the thrift store clothes my high school dress code forbade. Soon I wouldn’t have to take my earrings out in the parking lot each morning! I could ride my skateboard and smoke cigarettes right on campus!

Arizona State University was so close to home that I could bike the five miles there in half an hour, and drive in a few minutes. I knew the neighborhood well. My friends and I had been going to Tempe to collect concert flyers from record stores since before we had drivers’ licenses. Now we drove to Headquarters headshop to get parts for our bongs, and we knew where all the good record stores, resale stores, and restaurants were, and the video game arcade. Ted, the longhaired dude who worked at the headshop, even smuggled my recording equipment into a 1992 Mr. Bungle show for me, since he knew the band. Unfortunately, he didn’t meet me inside the venue to give me my equipment, so I couldn’t record the show. Thankfully, some other fan recorded it, and we saw Ted too much at the headshop to stay angry.

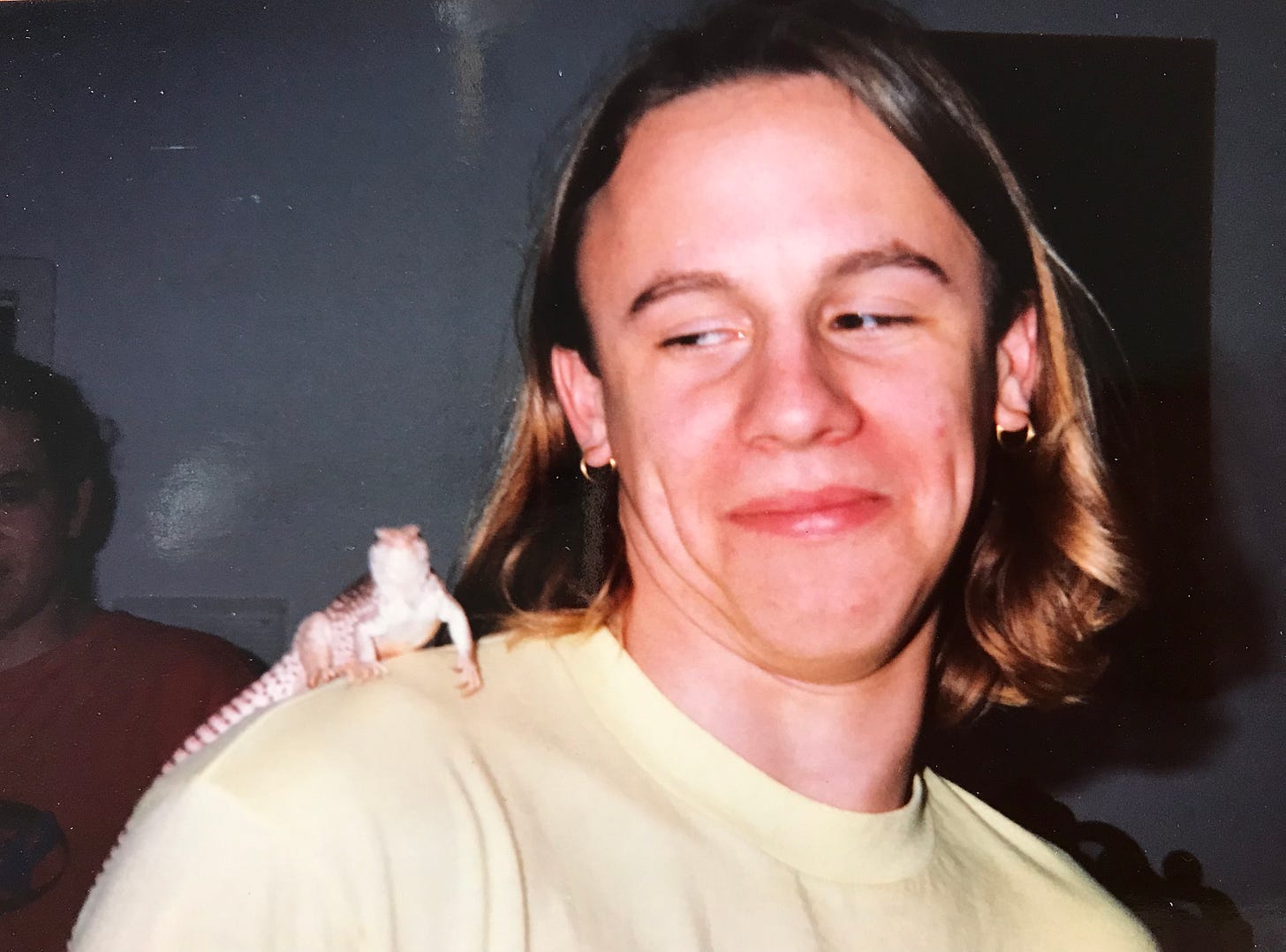

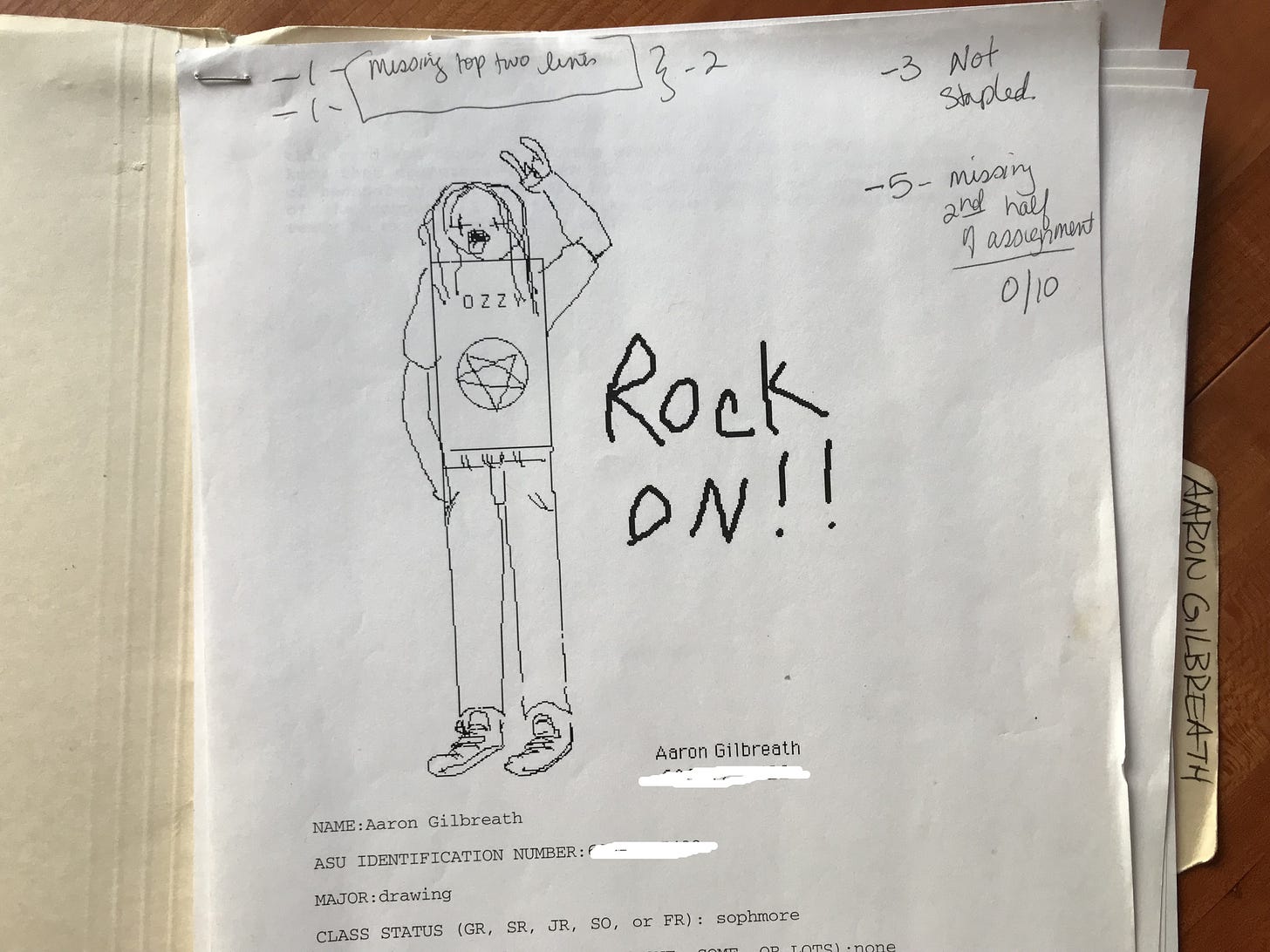

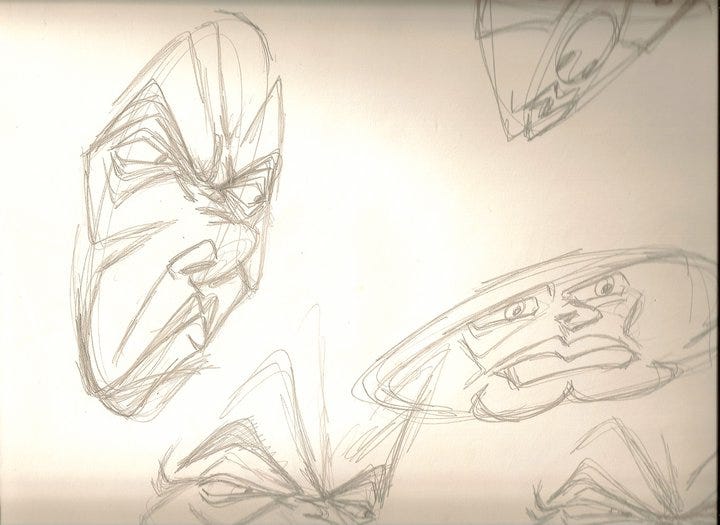

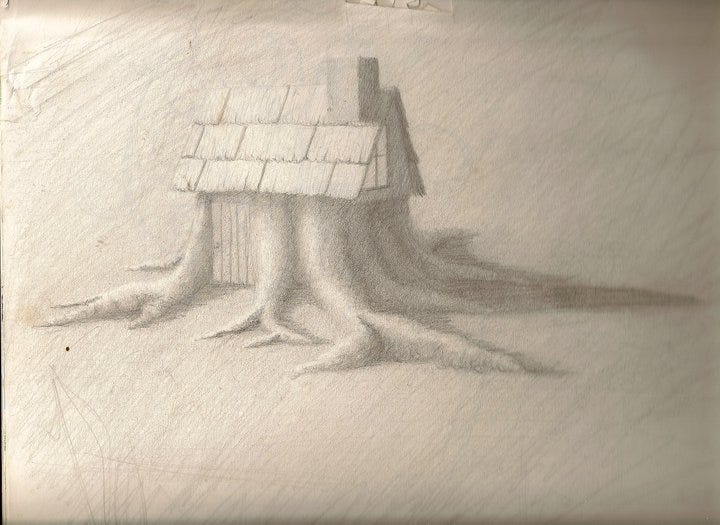

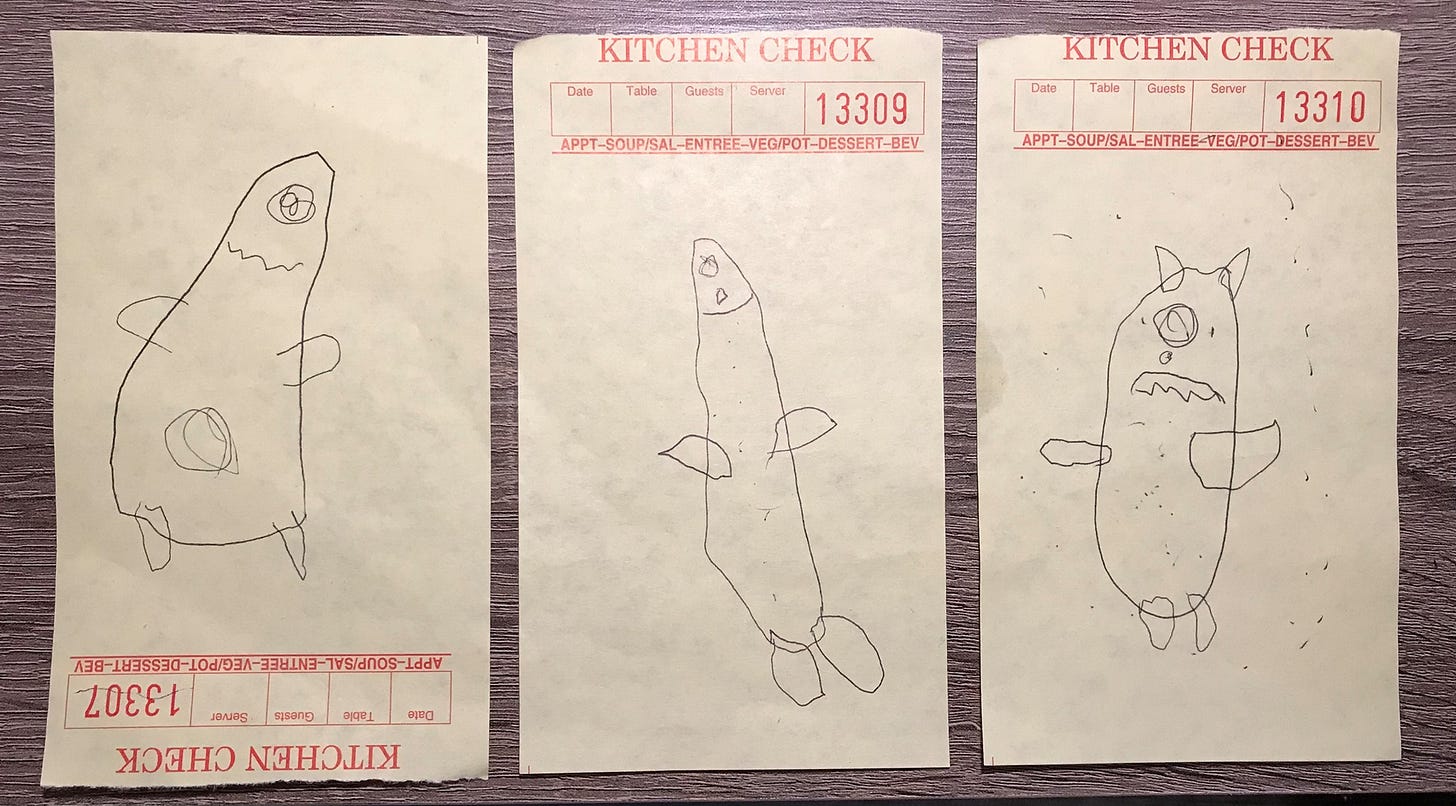

For me, high school senior year and freshman year of college felt a lot alike: My friends and I hung out, went to parties, hit the bong, went to shows and work, and took psychedelics. I still wore a 7-11 uniform vest in public for some reason. My college sense of humor was just as adolescent as it had been senior year. Look what I drew for my college computer class assignment. I was a moron.

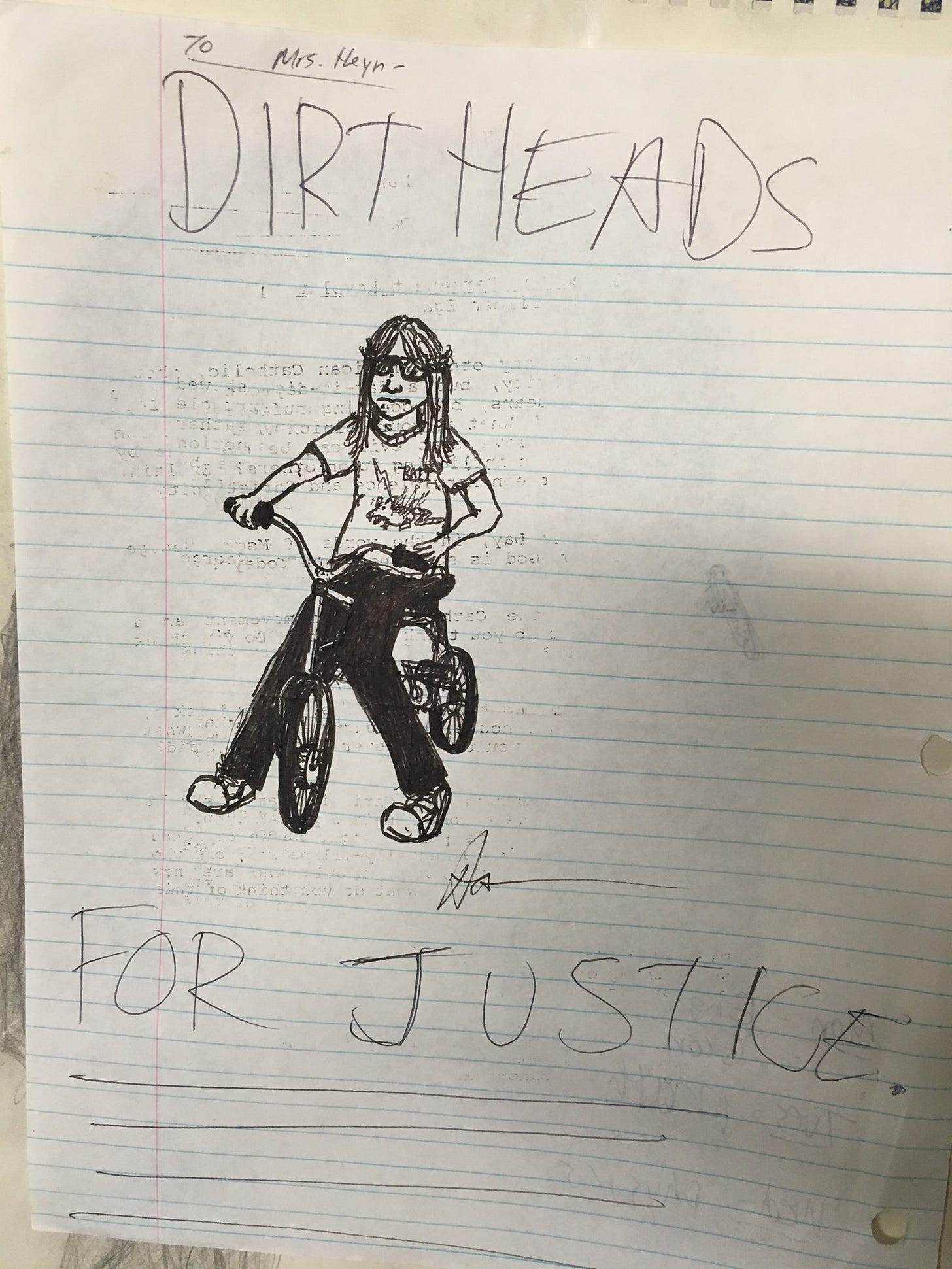

It was reminiscent of something I’d drawn in high school:

College only felt like an improved, more sophisticated version of senior year, except with more classes, more autonomy, more work hours, and more responsibility. Being on campus felt different.

My huge campus took up whole city blocks—a city in a city. The maze of new buildings was intimidating to learn. The student population was also intimidating: 30,000 people was way too many people. This was not an intimate Mills College experience. This was like studying at Costco. Everything was massive and industrial, like at a pig trough. If you drove to campus, you had to park your car in one of the huge off-site lots, which added a great distance to your travel time but provided a private place to smoke weed. To get around campus, you could walk, which took forever, or you could skate or bike, which was fun and practical. Skating was great, though the heat made it difficult.

At Arizona State University, spring semester wound down in early May, right when the 100-degree days hit, and classes resumed in mid-August, during similarly intense, monsoonal heat. In the scorching heat, I skated from a distant parking lot all the way to class. I’d arrive at my ENG 101 and GEO 101 classes covered with a ridiculous amount of sweat. Then the air conditioning would hit me and chill my slick skin. There were certain parts of my body that never dried. I eventually felt embarrassed riding a longboard as more frat boys picked up the habit. That took a while, though.

Sometimes I’d take my street deck with me to ride a section of perfectly sloped concrete, built at a gradual incline, outside the law library, to practice my rail slides. The way the smooth concrete divider descended made it ideal for rail slides, yet I never saw other kids skate it. I had it all to myself. Occasionally hungover at morning classes, definitely still partly stoned from the night before, it never occurred to me not to skate in 90° heat. When you’re young, you just do it. The kids who’d moved to Arizona from Wisconsin or Tennessee must’ve questioned their decision. One hundred degrees? How long does this last?

That first year, students asked each other lots of questions, chief among them, “So, what’s your major?” I didn’t have one. I was “undeclared.” Next to seeing concerts with friends, drawing was my main hobby. Despite the amount of skill that drawing required, drawing didn’t seem like a legitimate course of study, because drawing wasn’t a job. Hi, the company is hiring a new sketch artist, and we liked your résumé. As The Lips ripped through electric sets opening for a 1993 Stone Temple Pilots-Butthole Surfers package tour, I applied my thrift store-surf rat aesthetic to various school assignments, and I wondered if I’d ever find the right major.

As a freshman and sophomore, you could get away with not declaring a major. You had time to figure it out while you took interesting classes that fulfilled your elective and general education requirements. I took a full, five-class load each semester. Most were required filler like English Composition & Rhetoric.

While postponing the inevitable during my first three semesters, I chose interesting classes, like Geology 101, women’s studies, general art history, and environmental geology.

I wrote some great papers and some awful papers. Example A: A two-pager for sociology that I didn’t even title. The paper began: “Everybody wants to be beautiful, but not everyone is born with good looks and desirable features, which is exactly how advertisers sell some of their products.” The paper was about a single advertisement and the social construction of beauty. In the margin, the professor wrote: “Where is the ad?” I probably rolled it up and smoked it.

In my required Spanish class, I kept a list called “Bad words that are good to use” on the inside notebook cover. Conjugation bored me. So did the endless list of words to memorize like soltera, casada, debíl. Tengo quatro hermanos? No, Chinga tu madre pendejo.

For money, two of my brothers generously let my dumb ass work at their Subway sandwich franchises. And I worked on campus, where I stuffed professors’ travel vouchers in a rotating file cabinet, stoned, then I got to drive a golf cart around delivering campus mail. When I saw classmates, I’d give them rides. One time we drove the cart into a bush after I took it off-road in some wet grass.

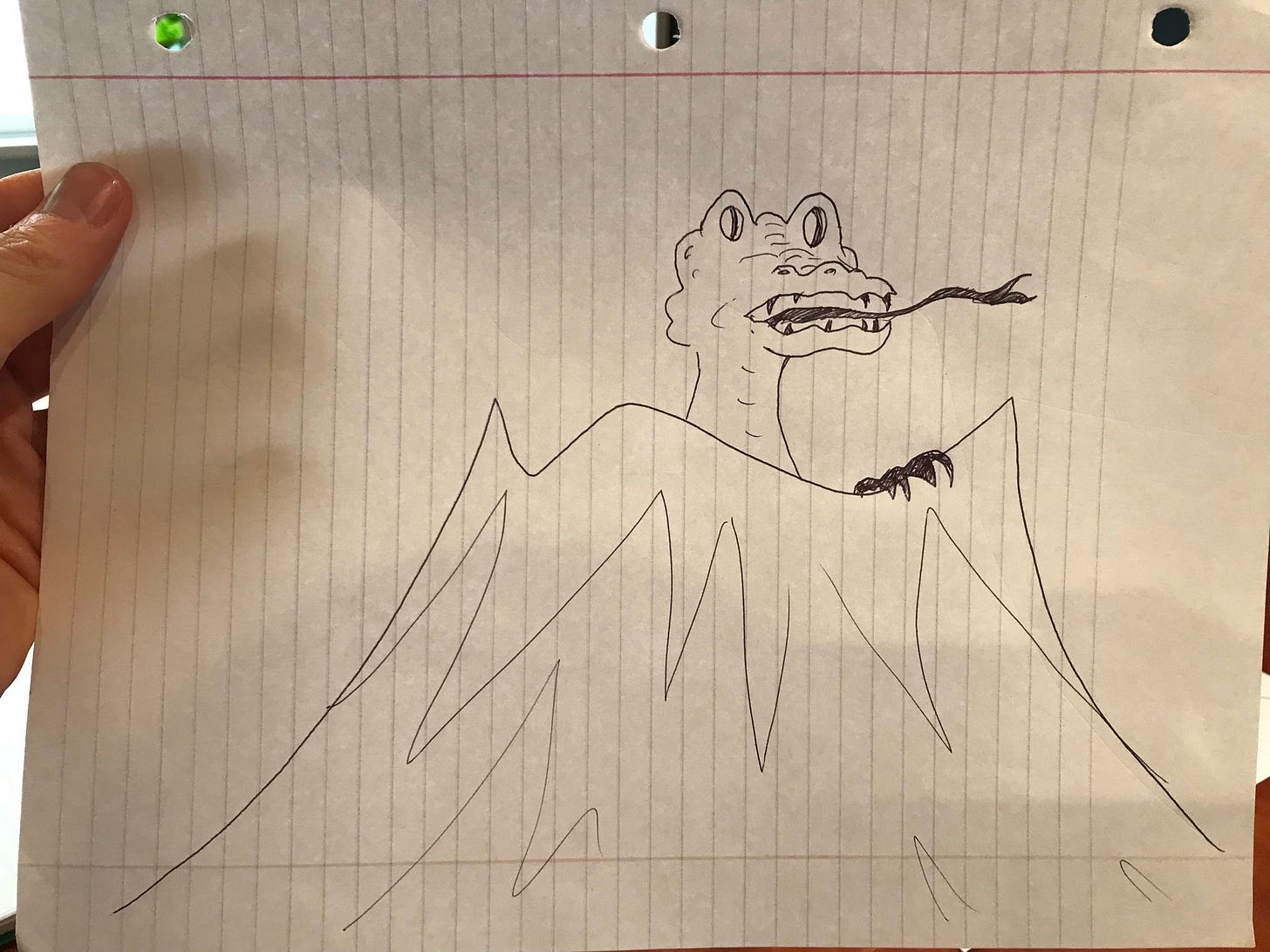

In the fall of ’94, I worked at Fiddlesticks Family Fun Park. I don’t remember how long that job lasted, only that I spent time tending the golf shop, video arcade, and, best of all, the race cars, which I cleaned, parked in rows, and monitored was drivers raced them along the circular track. Kids often drove these as wildly as I drove the campus mail cart. I was not the right person to stop adolescent mischief. One afternoon I tried to ride a cart like a skateboard—setting one foot on the back and pushing it with my back foot—and damaged my heel so badly that I had to wear a leg brace for a few months before I could return to actual skating. Convalescing in the Fiddlesticks golf shop on a rainy day, I drew some faces on company time, using the manager’s notepad.

Drawing, drawing, I was always drawing. Was my major right in front of me?

I don’t know when I started drawing, but it started young, and like most kids, I eventually graduated from crayons to pencils and pens.

I loved experimenting with watercolors and different textures of paper. My parents bought me nice pencils and sketchbooks from art supply stores, but I didn’t need anything too nice. I favored cheap pens, colored pencils, and simple sketchpads. My Granddad Gilbreath, a woodcarver, bought me art supplies and instructional drawing books. When I was young, my mom drove me to an art class where students learned to replicate three dimensions using shading and negative space instead of definitive lines—an idea that changed how I saw the world—but I came to prefer the cheap black and red pens Mom stole from work. They had hard edges and were easy to control. I was like John Muir hiking the Sierra: He didn’t need fancy boots or equipment. He only needed time and effort. Those pens taught me that practice and dedication mattered more than the materials, but encouragement was important, too. Everyone’s support made a big impact on my development.

Cheap supplies had their own challenges. Sometimes I had to stop myself at the start of a drawing, because I’d start doodling on a piece of yellow lined notebook paper, and when I could tell the drawing was going in a good direction, I realized I’d damned it to a cheap medium I’d never want to frame. Some of my best drawings exist on the worst paper, crisscrossed with college-ruled notebook lines. But in class, I drew in notebooks to conceal my activities. I was supposed to be paying attention to the lecture. I couldn’t bust out my good quality sketchpads.

My parents and I kept all my drawings, so it’s a real treat to see all the phases my drawing went through and my development.

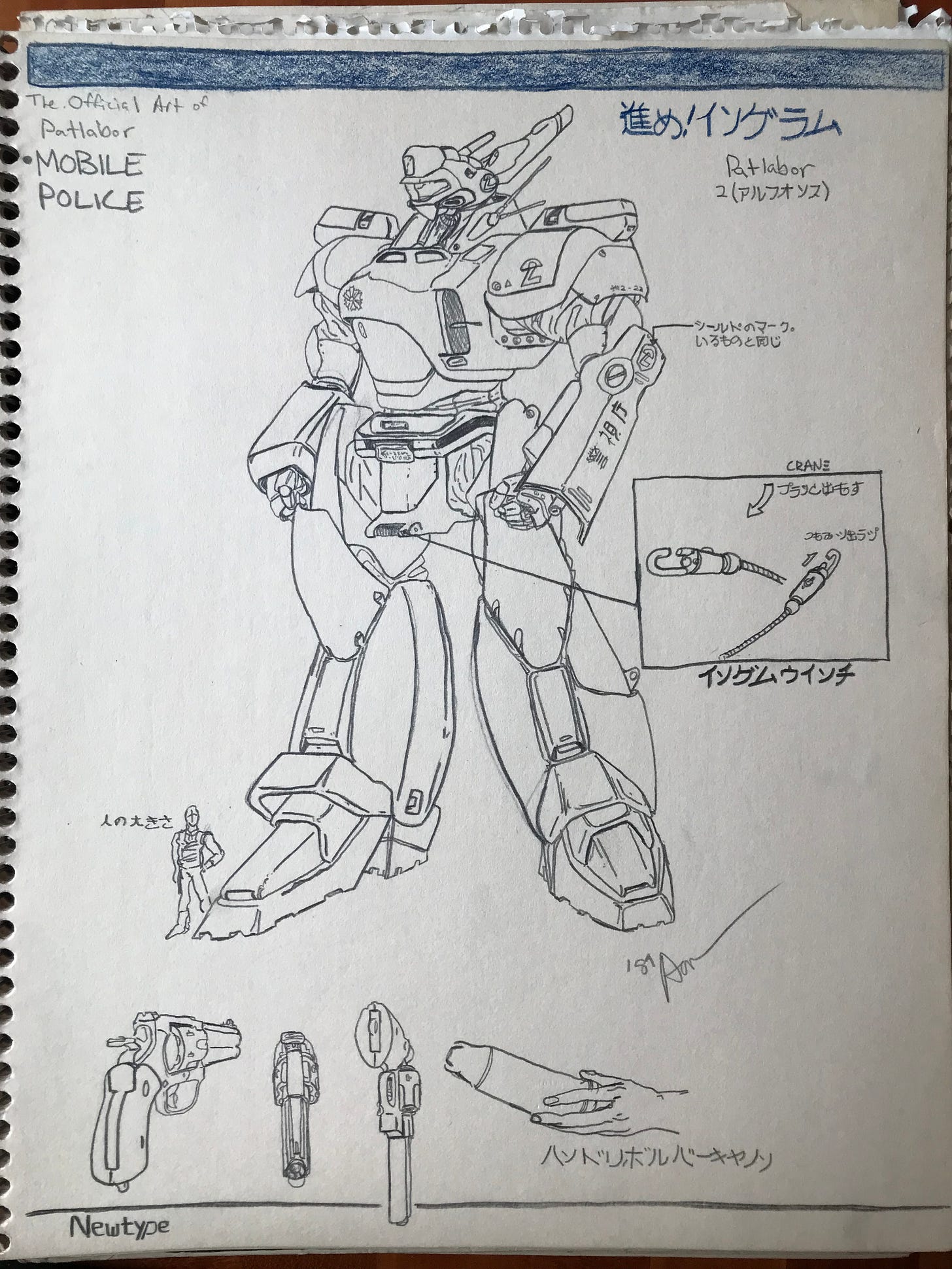

Between 5th and 8th grade, I was obsessed with the Japanese cartoon literature called manga. Once I discovered the TV show Robotech, the next three years were spent scouring comic bookstores for anything like it, assembling models of Japanese robots and mech-exoskeletons, and replicating the images in my sketchbooks.

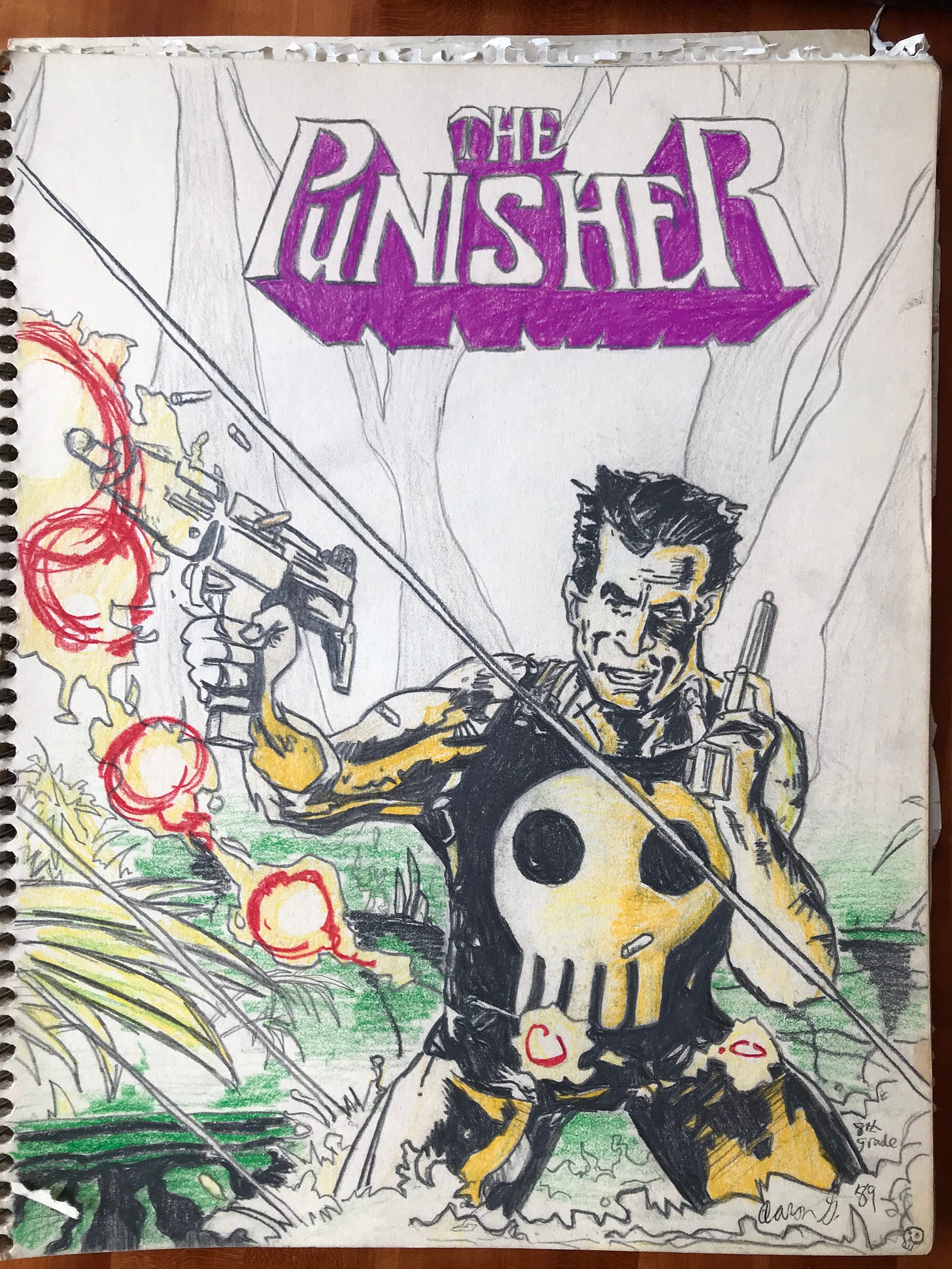

At the same time, during middle school, I loved American superhero comics, mostly Batman and The Punisher. These were violent, with lots of guns spraying bullets, but that also made them visually dynamic. I didn’t like violence. I’ve never been in a fight and or hit another person in my life. Their sense of motion, and the ways the artists rendered the comics’ dark style, just caught my eye.

I loved reading, so I made two fake books out of manila file folders and filled them with my own made-up Fragile Rock story lines—my first graphic novels.

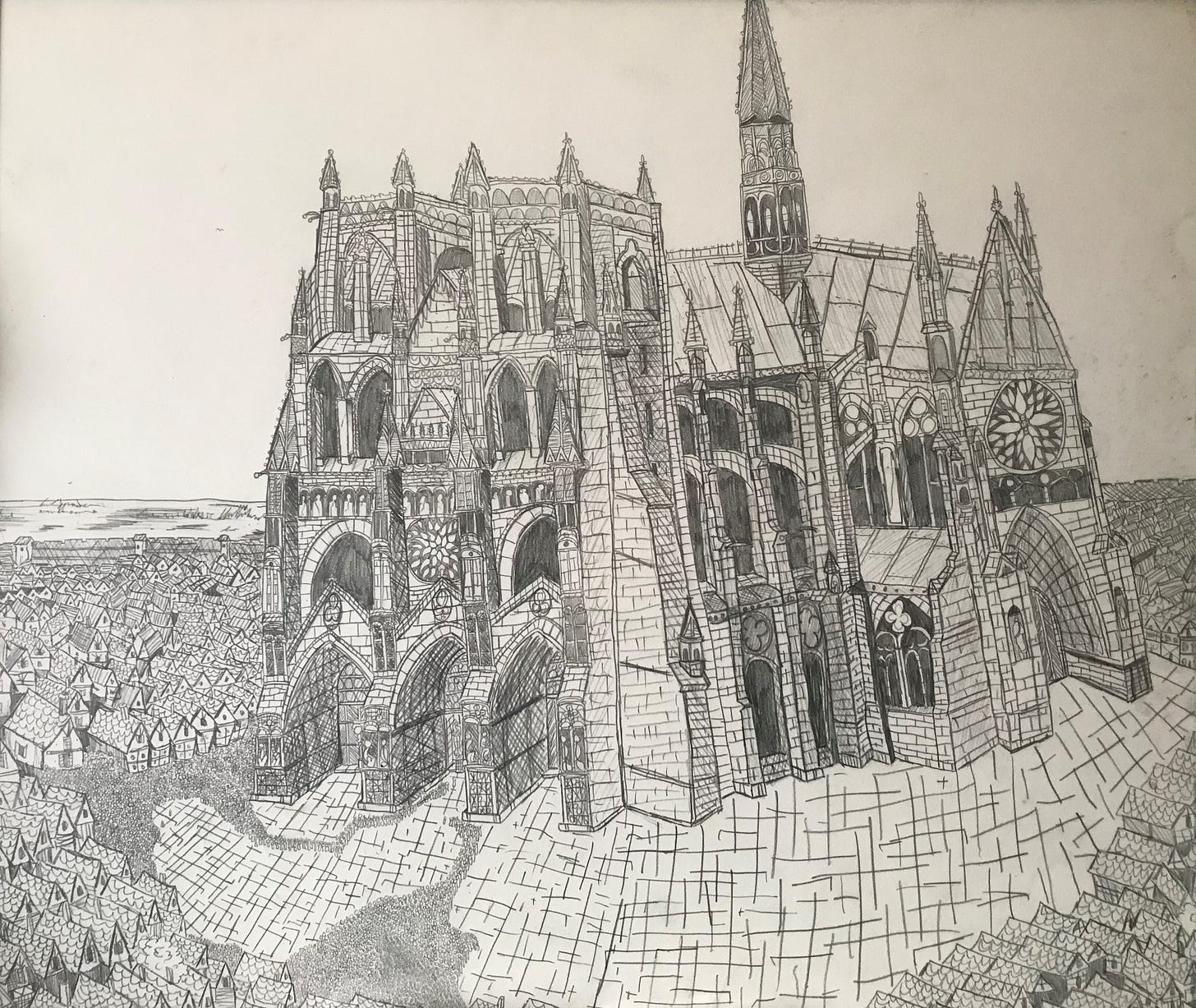

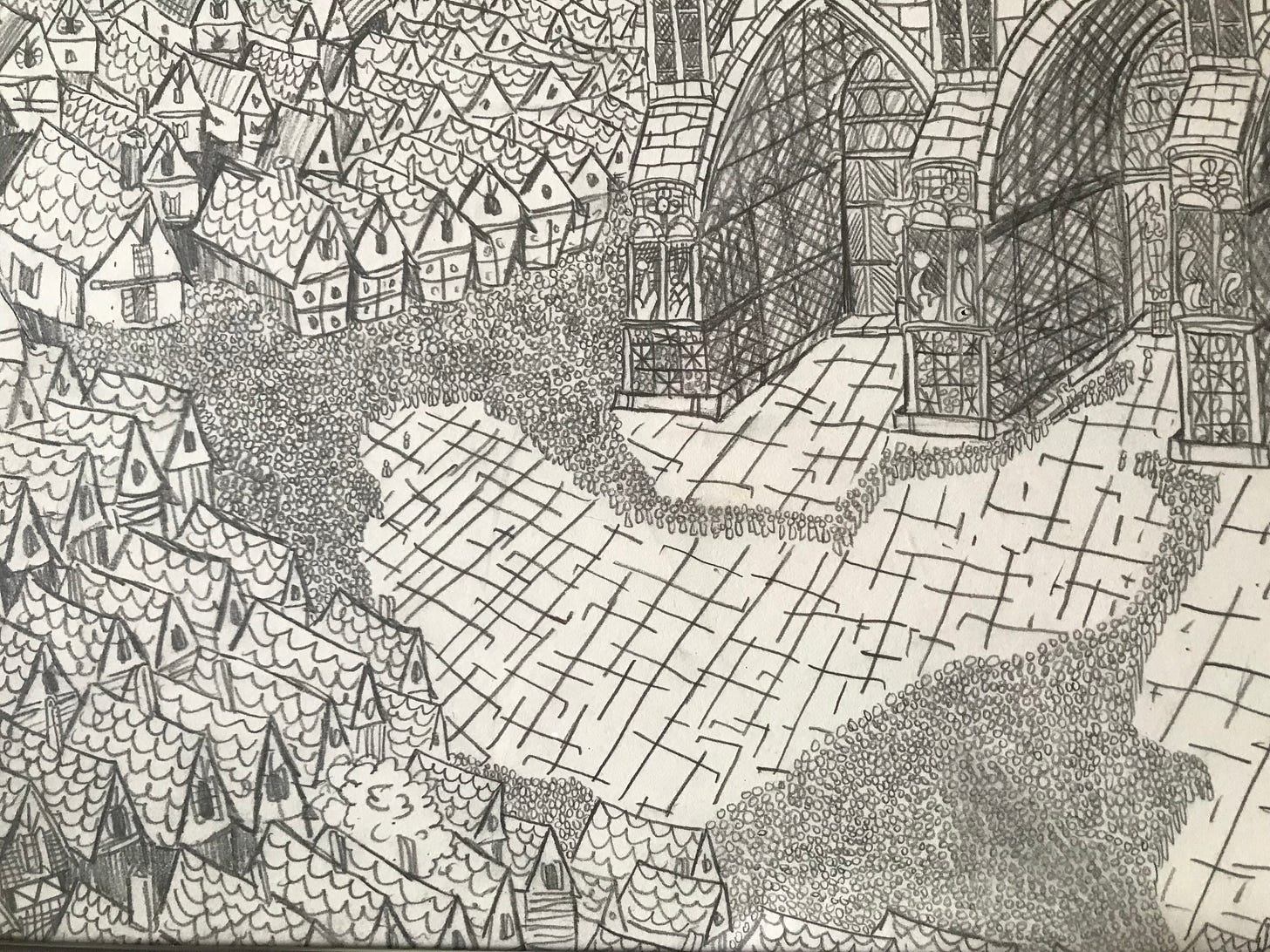

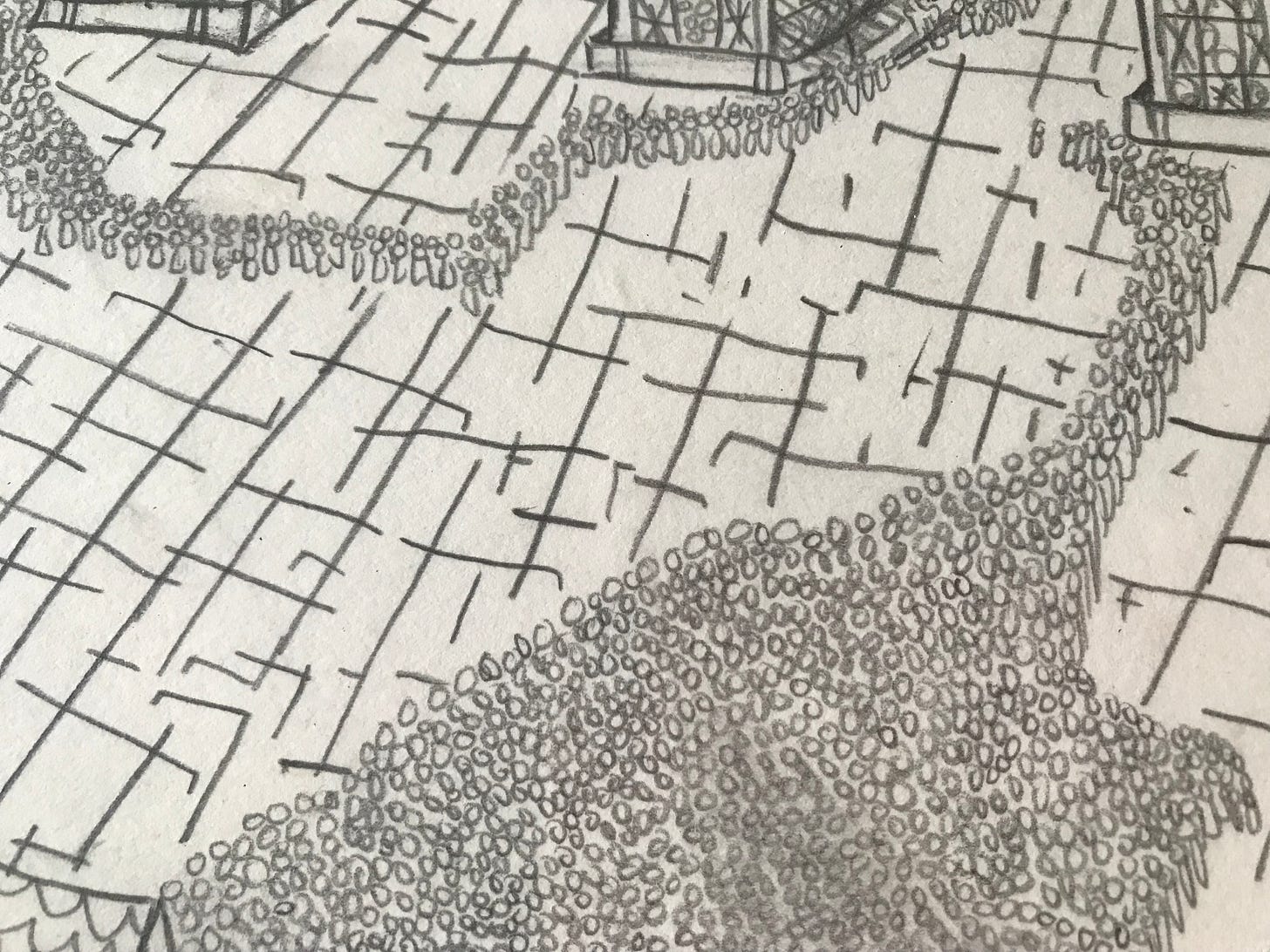

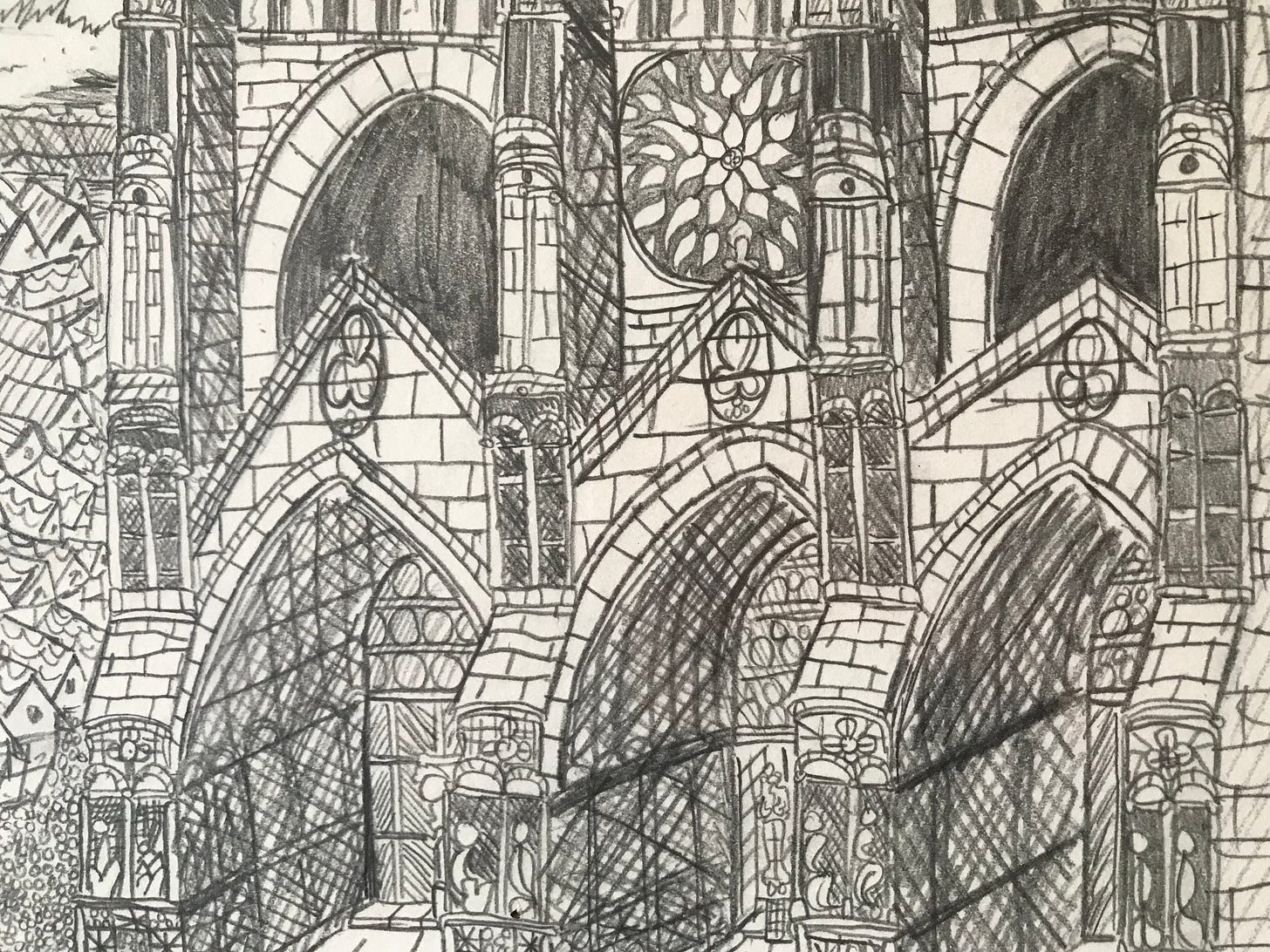

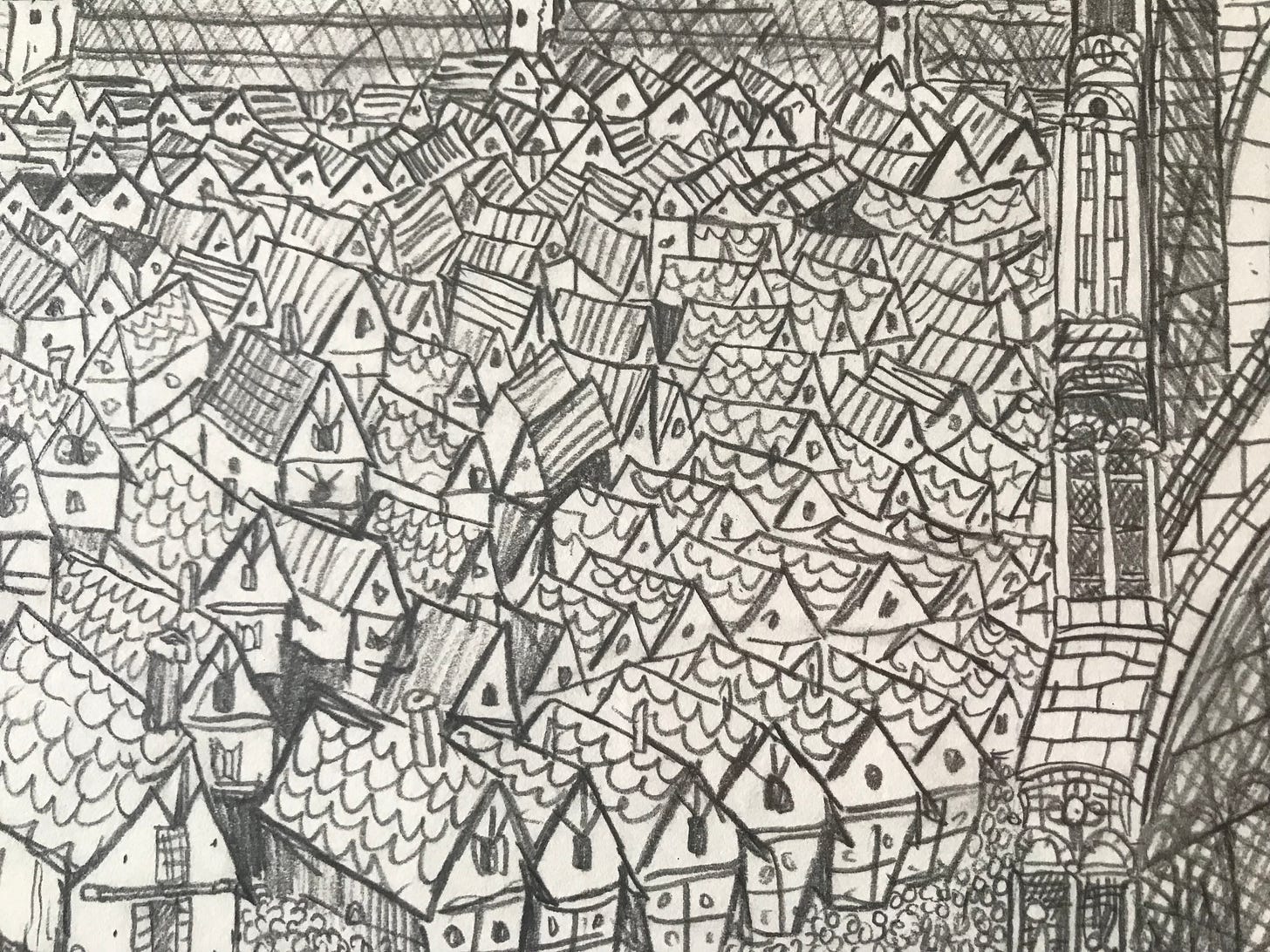

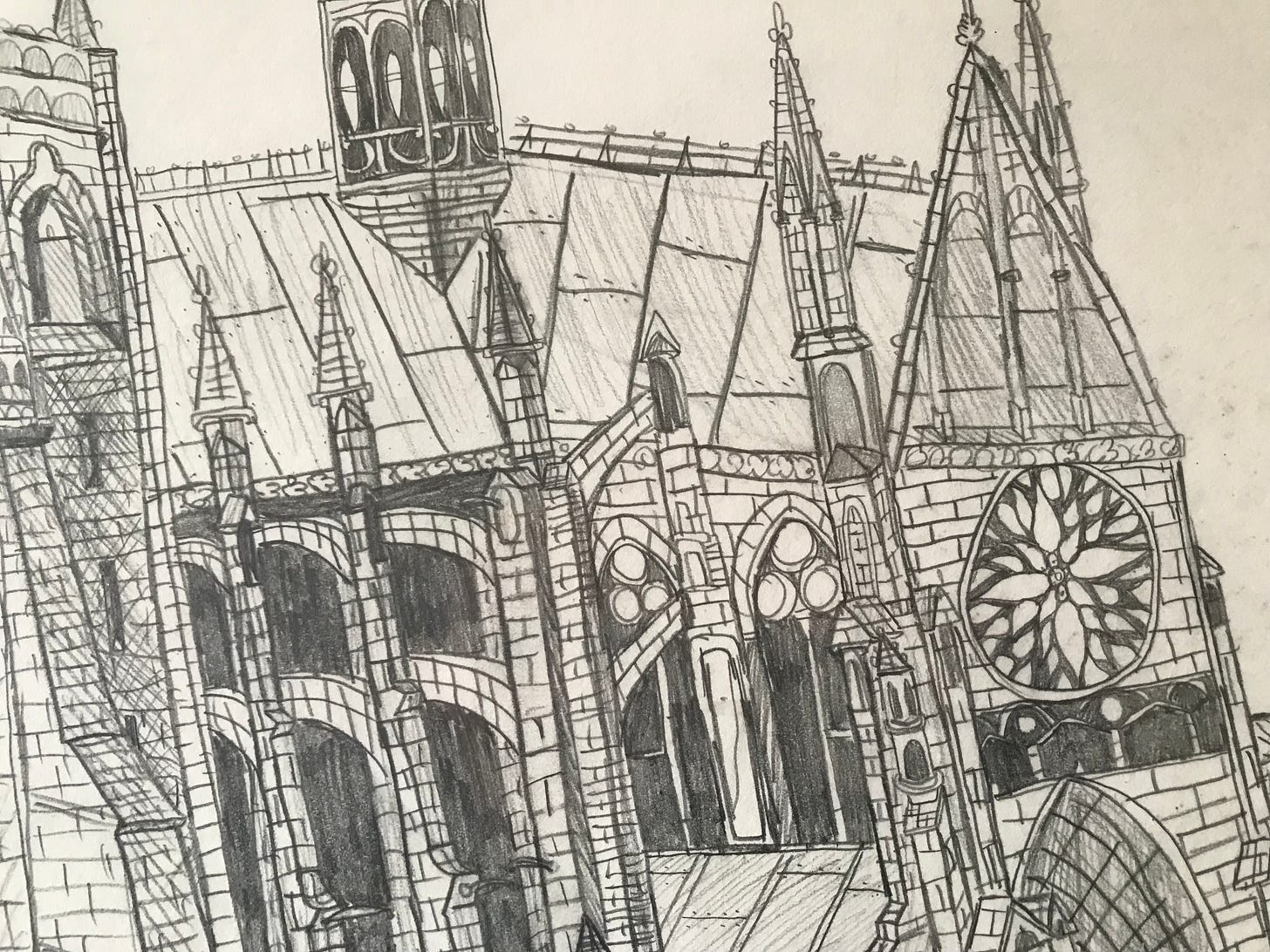

In middle school, I spent about a whole week drawing a drawing of a medieval church. At 26 by 22 inches, it was the largest single drawing I’d ever attempted, so I had to keep the paper on the dining room table since no other surface in the house could accommodate it. I was small, so I would lean over the page at different angles, working on different sections but failing to pay sufficient attention to unifying the section, which explains why the finished drawing leans in a way: I didn’t back up enough from the image to assess how my body’s position was warping the perspective in two-dimensions. It was a good lesson, and I still loved how it turned out. My parents framed it and hung it in our upstairs hallway for all to see. For years I passed it walking to and from my bedroom, and it filled me with pride. The whole thing worked best from a distance. Close up, the details revealed their inaccuracies. It was fun getting lost in details.

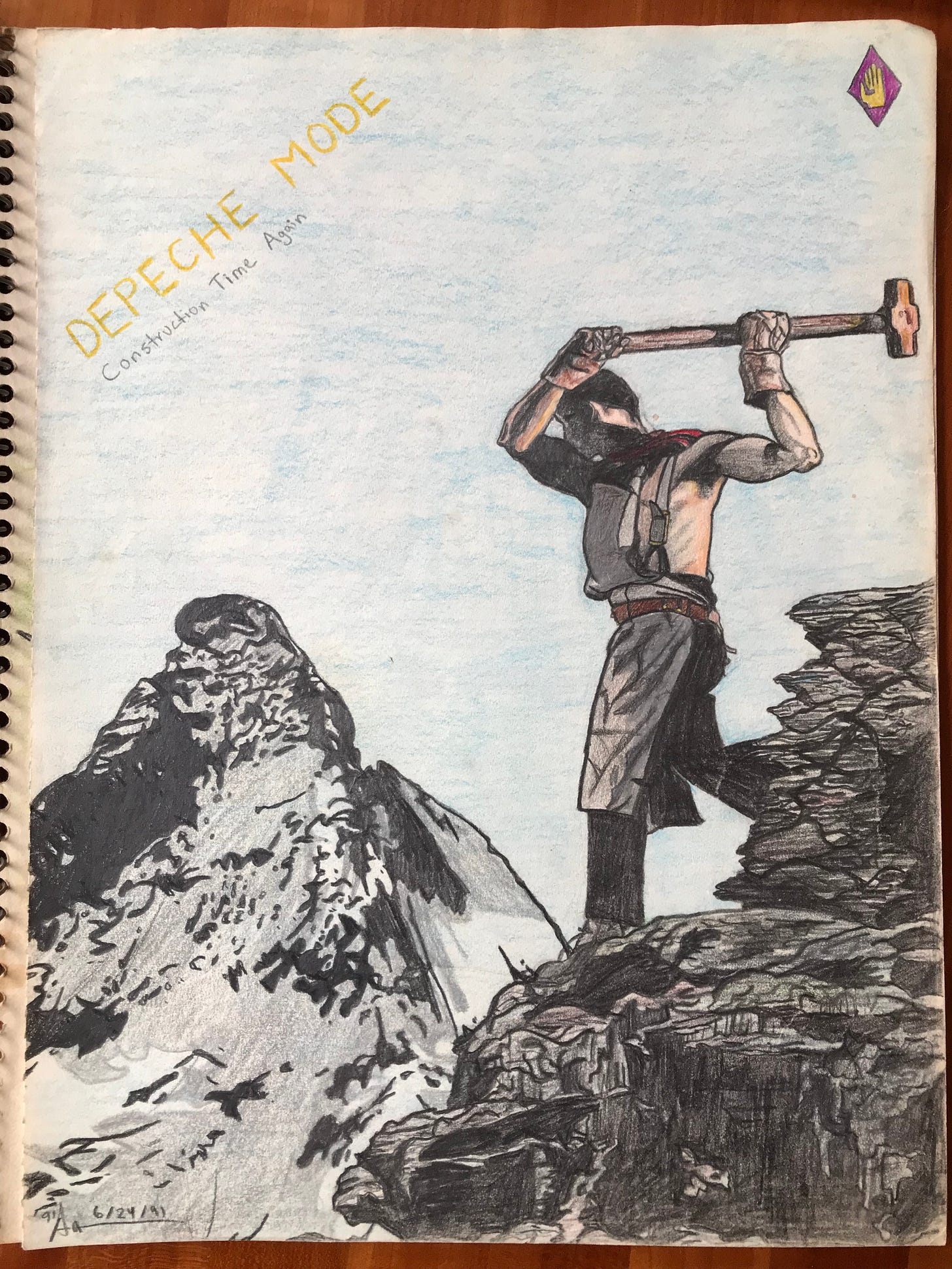

In middle school, my love of Depeche Mode and surf culture had me drawing DM album covers as frequently as palm trees and breaking waves. In middle school, my subversive nature also meant I liked to pass drawings around during class, letting friends add funny images and thought bubbles to whatever sketch I’d started, before they passed them back. It was a dare: Would the teachers catch us? It was also an artistic form: an evolving collaboration. I loved drawing in classmates’ yearbooks, too.

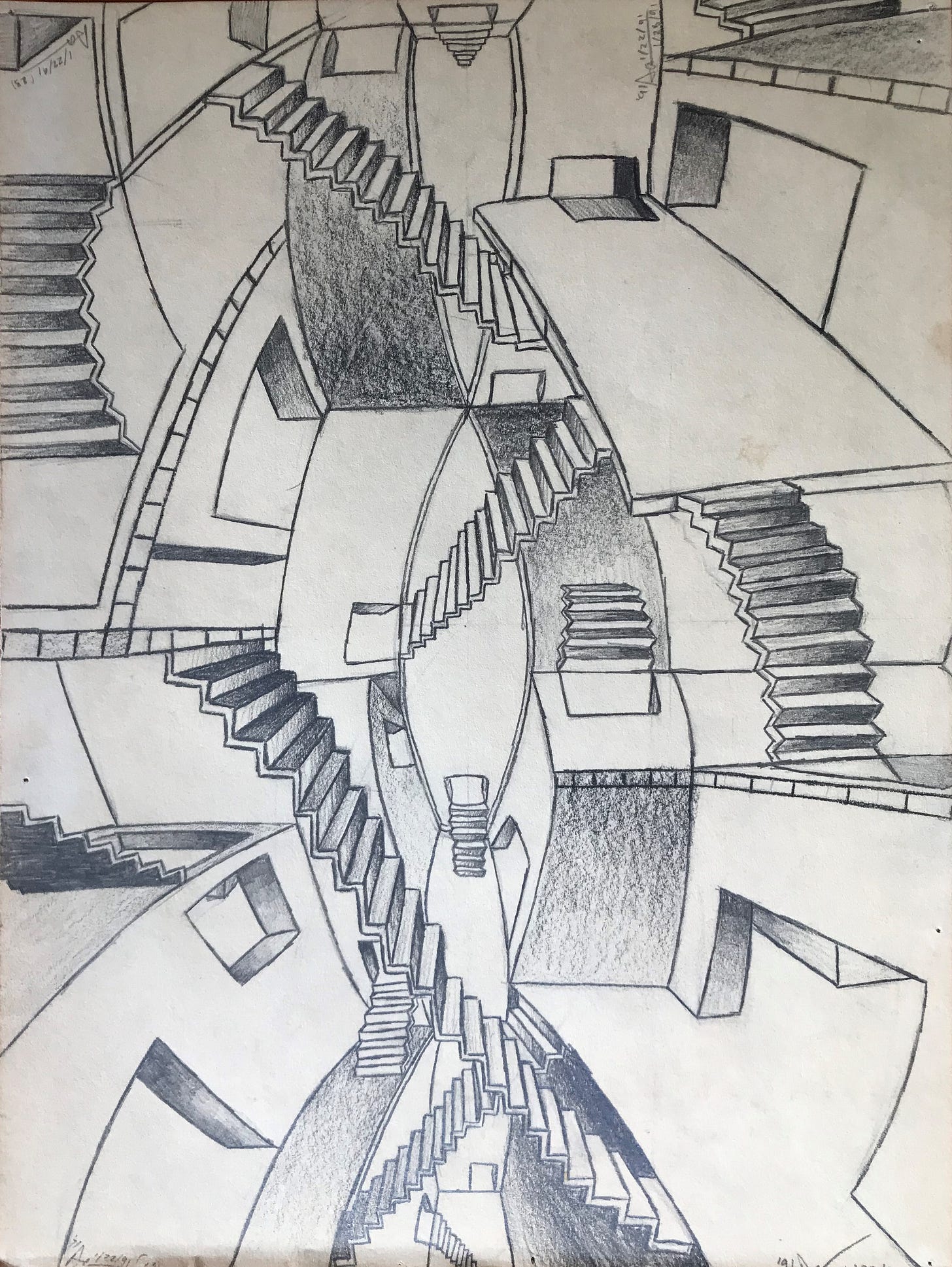

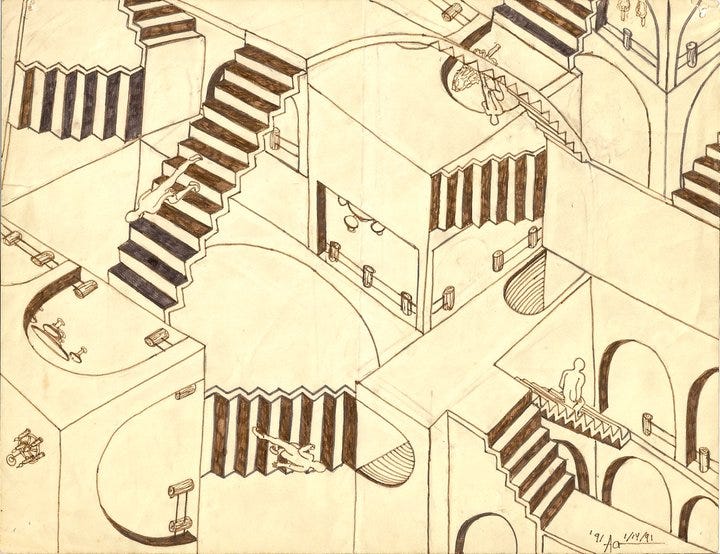

In high school I went through a hardcore MC Escher period, where I read about him and drew as many of his drawings as I could. My grandmother had an Escher book, and the geometries and fluid sense of scale and gravity—and the way every architectural element interlocked, either upside down or right-side up—fascinated me. So I copied his drawings to try to understand how they worked. This is an original inspired by Escher, drawn during some high school class, probably Math, in 1991. I couldn’t stand most Math, but I loved geometry. Escher involved geometry.

I would draw a geometrical superstructure first, sketching faint lines to keep everything in perspective, then I’d draw map the stairs and doors and architecture over that.

Since I didn’t know what else to do, I picked a college major in a discipline I was good at. My parents were justifiably concerned. What did you do with a drawing major? Go back and get your business degree? A drawing major didn’t comfort me either, but I needed something to start narrowing down my options until I figured out my career.

ASU’s art department had some beautiful buildings. It also put some of its art classes in a cluster of old ugly buildings on the northwest corner of the giant campus. This seemed like one of the older parts of campus. Some workshops were in a tall, dark grey, institutional building, where students smoked in the shaded narrow stairwells. Other workshops were in a funky set of one-story buildings that looked like the part of Tatooine where Luke lived with Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru in the first Star Wars. I remember plain stucco that reflected glaring sunlight. Narrow passageways ran between buildings, creating little mazes. Feet crunched gravel as you searched for the right door, and big square air conditioning units hummed all over, covered with dust. It felt old. It probably looked different than I remember. Students carried tall canvasses between rooms and had little containers of art supplies. It felt like the university didn’t want us around, or at least didn’t want us polluting the rest of the student population with our drugs or ideas, so they stuck us in this leper colony. That made me feel special, though it’s probably inaccurate. I did love the art school’s location, though. I’d always felt most comfortable on the edge of things: the back row of class, the front row of concerts, the cliff above the coast, the furthest cubicle in the library study area. As a fringe dweller, edge spaces were my habitat, including the edge of society.

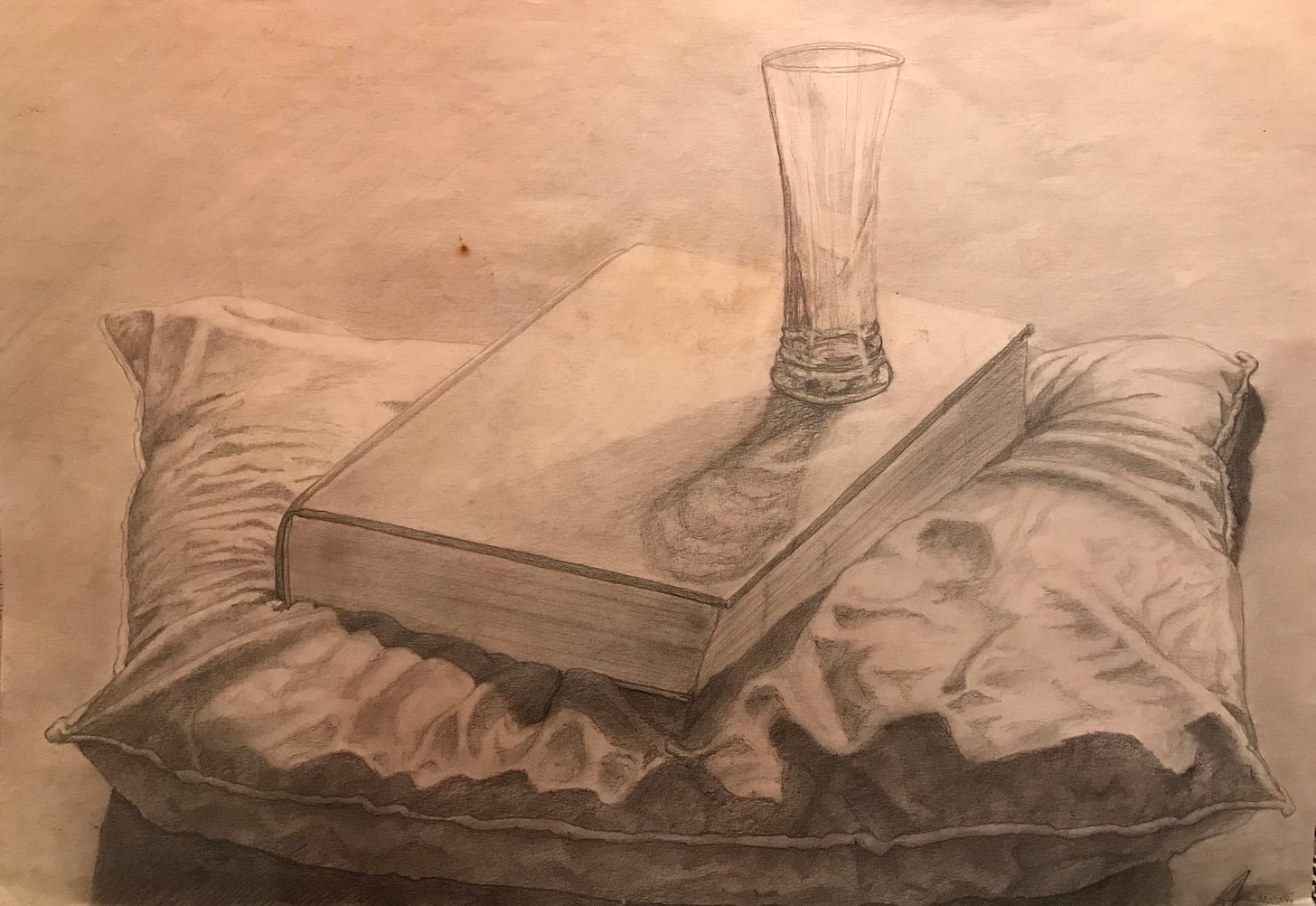

It was fun among the freaks. In my first studio class, we sat in a circle for three hours, drawing inanimate objects the teacher arranged in front of us: collections of fruit; a bull skull draped with cloth, things with texture and shadows—the classic still life.

On breaks, we students often smoked cigarette halfway through, crowding inside a narrow stairwell outside the building, filling it with smoke and talking about class and big arty ideas. It was cool to hang with older students and kids who dressed differently than me. I loved those breaks, but I feared how we’d all fare once we left this comfortable campus bubble. Did all working artists start like this? Where Wayne Coyne and Michael Ivins watched touring punk bands and wondered how they could tour and record, too, I wondered how painters and drawers and the writers of our schoolbooks got paid. Did bands like The Flaming Lips have back-up plans? I guess Coyne could always go back to Long John Silvers, but that seemed a failure to truly maximize his artistic ability. How do you monetize weird talents?

“We really wanted to get out of Oklahoma City and see the world,” Coyne told Option, “we just had no idea how to do it.” I wanted out of Phoenix and wondered the same.

The ASU art department’s publicity materials said vaguely worded things about how their program prepared students to pursue creative careers, but how specific positions often depended on the student’s particular concentration—meaning, design was probably more practical than drawing—as well as receiving additional education. Although nowadays, the ASU website states that students who complete the BFA degree program can earn as much as $77,700 as “Multimedia Artists and Animators,” with additional certifications, and as little as $35,180 as a “Craft Artists,” (-1% growth rate), I had no such detailed reassurance about my prospects. Admittedly, I probably didn’t ask anyone in the department for examples of future drawing careers, but I also had my eyes on an early death or saving the world as an environmentalist instead of longevity.

If art school offered any promising career paths, I didn’t stick around long enough to find out. I was an interloper, just passing through while I searched for my true path. Art history classes were fascinating, but I didn’t need that level of historical detail. I didn’t envision myself as an art teacher one day. Had I known about design majors and how my drawing skills could actually earn me big bucks working for advertising agencies, I still wouldn’t have stuck with visual art. I didn’t care about money back then. I just liked doing what was fun. How impractical. Visual art and the practice of drawing were part of something larger for me, I didn’t yet know what, but all the dots finally connected later when I discovered my calling in nonfiction writing.

All the weed I smoked didn’t help me think about this clearly. It certainly influenced the way I drew. I drew a lot of faces. I started trying accurate, realistic portraits. Portraits were difficult. It’s hard to draw a face that looks like the person it belongs to, because what elements of a face make them recognizable: their eyes? Their jaws? Their noses? All of those things combined and more. Getting the gestalt was a challenge, and I enjoyed the challenge of portraiture.