24-7 Seattle: A Trip to Hallowed Ground

How a family vacation became a rock 'n' roll pilgrimage during the Grunge era.

In the summer of 1994, my parents and I took a family vacation to Seattle. It was our first time in the Pacific Northwest, but thanks to music, I felt like I knew it.

My mom’s father had just vacationed in Seattle and returned home to Arizona raving. “It’s beautiful,” he told my parents, “so green and lush. You have to see it.” We flew up that summer. I fell instantly in love with both the city and the region, and on our third day, while sitting under the Aurora Bridge drawing the arched structure at night, I decided I would move here one day. Six years later I did. Of course, I’d spent most of high school training for this moment.

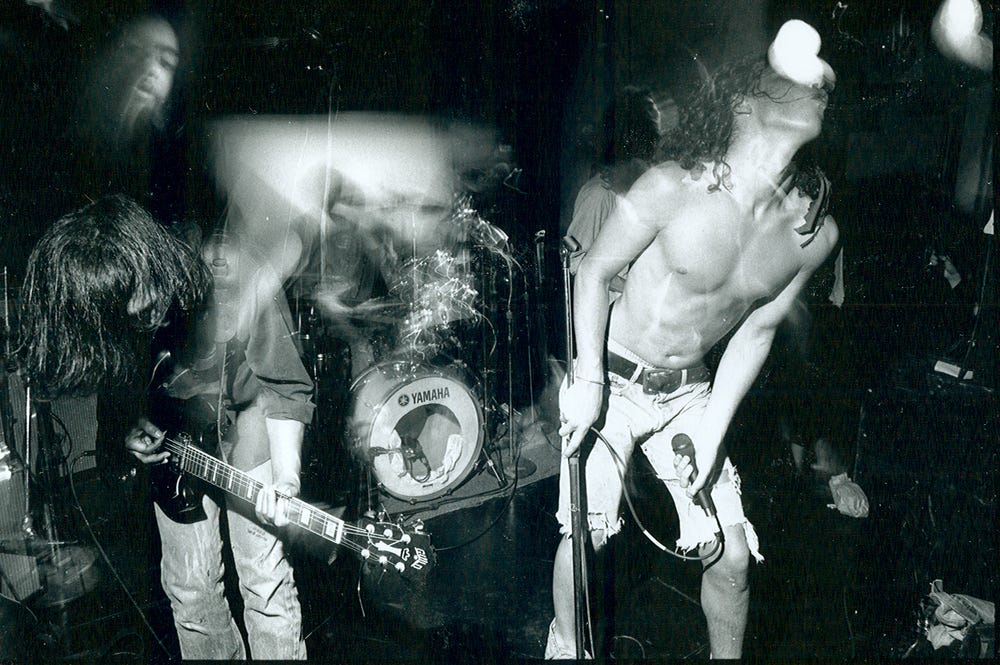

During the first half of the ’90s, I listened to Northwest bands, binged the concert footage in the movie Singles and its potent soundtrack, and read more about Seattle in Rolling Stone and Spin magazines than I’d ever read anywhere about my native Arizona. It started with Mother Love Bone in 1989. That led to Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Nirvana, Mudhoney, Cat Butt, Alice in Chains, and back to the U-Men in pre-Grunge Seattle. Sub Pop photographer Charles Peterson’s dynamic images defined my idea of the Northwest underground. With their hypnotic tracers, swirling hair, and constant movement, everything looked so energized in this rock ‘n’ roll universe. Stagediving, head-banging, fans pressed against the stage—I wanted that. Everyone did.

Thanks to Sub Pop’s effective marketing of this offbeat city, and MTV’s insistent messaging about the new cool music, kids like me felt a sense of ownership, that we not only knew Seattle, we belonged to it. Of course that was ridiculous—no wonder Seattle natives loathed the hordes of visitors—but that’s how I felt on the flight from Arizona. Looking at all the skyscrapers and upscale shops in downtown Seattle now, it’s hard to picture Seattle ever being offbeat or funky, but back in the 1980s, big touring bands used to skip the sleepy city on national tours, only going as far north as San Francisco. This left the place ripe for exploitation as its music evolved in a vacuum.

Sub Pop’s co-founders Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman didn’t apologize for exploiting Seattle. Punk rock rejected success. Early ’80s indie music values rejected success. Sub Pop was punk but embraced success. In fact, they were punk because they embraced it. What was wrong with doing well? With so much incredible music all around them, they decided to bring it to the world on a massive, lucrative scale. Why should talented musicians have to work day jobs if they could tour and score hits? By modeling themselves after the hit factory labels like Motown, Sub Pop used attractive record packaging, a unified look and sound, and straight up hype to sell their label and city even more than the music. “Seventy percent of what Bruce and John say is a lie,” Sub Pop publicist Nils Bernstein said in the music doc Hype! “But it serves them well!” Seattle became the biggest thing in rock since the invention of rock itself, a city which generated as much screaming frenzy as The Beatles had in the 1960s. Granted, by 1994, Seattle was speeding toward the end of its cultural moment, along with the decline of so-called alternative music. By the time our plane landed at Sea-Tac Airport, Kurt Cobain was dead, many iconic Seattle bands had broken up or permanently graduated from little clubs to big venues, and the world would soon lose interest in the manufactured idea of “Grunge.” Corporate interests had spent so much time commodifying and exploiting Seattle culture that much of the music scene’s original heat had cooled, and Seattle had filled with wannabes and aspirants, diluting the once concentrated talent pool with their fake Eddie Vedder voices and arena-rock ambitions. “What I’m hearing now,” Billboard’s associate director of retail research told Time in 1992, “is that bands from L.A. and the Midwest are moving to Seattle and telling record companies, ‘Yeah, we grew up here, and this where we make our music.’” That didn’t matter. I was pumped.

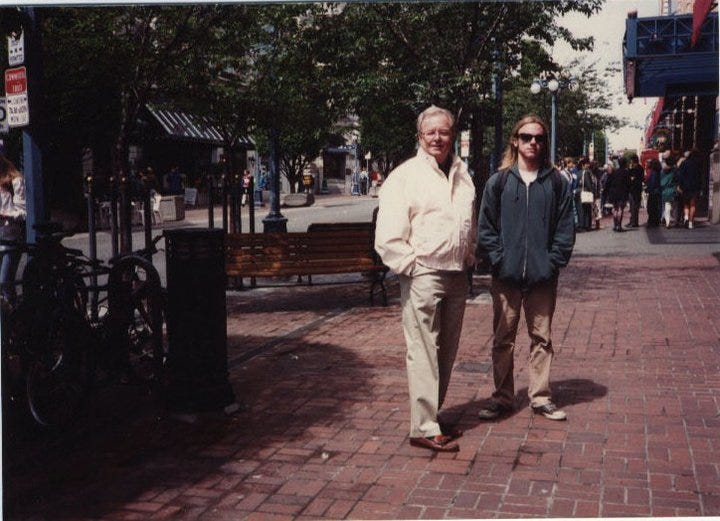

I was 19, a freshman in college. I had longhair and aggressively red Converse All-Stars. I wore plaid shirts and corduroy pants that I bought at thrift stores. To me, this was more than a family vacation. This was a rock ‘n’ roll pilgrimage. Visiting Seattle was like visiting the center of the universe, because this was the city where some of the world’s most badass musicians wrote their in-your-face music. It was a city with underground clubs like the Off-Ramp and Crocodile Café where audiences could watch bands at eye-level with their Doc Martin boots. It was a city where you could apparently stumble onto an Alice In Chains concert inside a warehouse on a wharf, like in Singles. Forget L.A. This place was real, not a backlot dressed as a city. Without ever setting foot there, I knew everything about it—an expert!—because I’d been feed this facile narrative by the capitalist culture factory.

“Seattle’s the Real Deal,” read a 1992 Time headline. “Seattle boasts for thriving independent record labels; six key music venues, like the Vogue, in the downtown area alone; and nearly that many recording studios.” That was a thousand times better than my sprawling, cookie cutter, chain-store desert car-town. As a restless teen, the grass was always greener to me, especially in the timbered kingdom of Seattle, and the music up there just sounded better.

“The Seattle sound is cussed, aggressive, incisively individualistic,” Time wrote, “and it comes, like matching tie and handkerchief, with its own attitude: cut down on flash, look regular, sound loud and sound off. ‘People here do what they want,’ says Terry Date, producer of Badmotorfinger for Soundgarden, which has toured with Guns N’ Roses.” That described the ideal environment for a loudmouth, rebellious punk ass like me. But also, objectively, so many of these bands were just killer bands. It’s easy to lose sight of that fact. So much idiot swill was marketed around the music, from so-called Grunge fashion to Grunge aerobics, but the music was good. Initially it was raw, unadulterated, unpretentious, over-the-top, playful yet loud, and it wasn’t a performance. Bands plugged in their equipment and banged it out. As legendary English record producer Martin Rushnet said in Hype!: “It’s taking rock right back to its basics, which is go up there and make a hell of a noise, and make sure you play music your parents don’t like.”

My parents had mapped all the tourist attractions: Pike Place Market, the Space Needle, a seafood restaurant institution named Ivar’s. I had my own list of attractions: The Moore Theatre where Pearl Jam filmed the “Even Flow” video; The Paramount Theatre where Nirvana filmed the crispest concert footage of their short career; and the OK Hotel, where Matt Dillon worked as a waiter in the movie Singles and Nirvana performed “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for the first time live. Maybe we could drive by Kurt Cobain’s house on Lake Washington, too.

Fans made music pilgrimages all the time. They visited Jim Morrison’s grave in Paris, visited the London crosswalk on The Beatles’ Abbey Road cover, and the Mississippi crossroads where Robert Johnson supposedly sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his guitar chops. Hell, you could visit Jimi Hendrix’s grave here in Seattle. Matt Dillon’s character in Singles did. This was my pilgrimage. I mean, I didn’t tell my parents that. They wouldn’t understand.

My dad had violently ripped Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love CD from the car stereo while driving me to college after Chris Cornell started screaming “I want to fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck you!” I’d recently crashed my car, so he was already irritated. And who can blame him? My university studies didn’t make up for the sinister direction my longhair and loud music suggested my life was going, so I kept my sightseeing agenda to myself. As we wandered past tchotchke shops and Ivar’s Acres of Clams on the tourist trap waterfront on our first day in town, I studied passersby’s faces in search of my favorite rock musicians. Was that Kim Thayil? Was that Mark Arm? It wasn’t. Icons would never set foot in a tourist trap like this. But I kept my eyes peeled as we walked downtown and through neighborhoods that looked like the ones in Singles. Chris Cornell and Mark Lanagan were around here somewhere, and L7 and Dickless, too.

No matter how silly this all sounds in hindsight, it thrilled me at the time. Three consecutive Lollapalooza summer tours had crop-dusted America with the sound of alt rock, and my friends and I attended every tour. But after getting hammered by MTV with Pearl Jam copy-cats and Stone Temple Pilots’ poseur singer and his stupid red hair, and all the Blind Melon “No Rain” one-hit wonders, I wanted some evidence that musical reality—even humanity—existed beneath the alternative music industry. For outsiders, Seattle became a brand, an idea, a fantasy. “In Europe they just started to put stickers on things that just said ‘Seattle,’” remembered The Walkabouts singer Chris Eckman. “That’s all the sticker said.” It reminded him of the U.S.D.A.’s inspection stamp on meat: “Seattle. Stamp it!” But a visit to Seattle offered proof that this alternative music frenzy wasn’t all manufactured. It came from somewhere, a regular city where regular people drove regular streets to their regular jobs and some of them just happened to grow into rock ‘n’ roll deities. A pilgrimage humanized the gods. And humanizing was the opposite of abstraction. By 1994 even I was sick of hearing Kurt Cobain whine “What else should I be? All apologies.” On one side, it was like: Get over it, dude. So many white alternative ’90s rock guys just whined, whined, whined. But part of me knew that experience came from somewhere. These people in the music videos were still just people: people with childhoods, people with trauma, people with parents who left them or parents who loved them and things they wanted to prove. Here in Seattle, I unconsciously wanted something deeper than these products. I mean, yes, I was a product. Age would eventually give me that perspective on the culture economy. Adolescence just gave me excitement.

I hid my excitement behind dark sunglasses and a detached grin.

Even four years after Mother Love Bone’s singer Andrew Wood died, the Seattle I arrived in was the place where the fallen rock god posed beside a sculpture wearing a big weird hat and white bug-eyed glasses.

It was a city inhabited by ghosts whose paths I’d arrived too late to cross. I’d listened to Love Bone’s music on my Sony Walkman for so long that I couldn’t help but feel connected to this lost soul. Here in his hometown, he felt closer than he ever had, but still out of reach. Mother Love Bone would always be the band I discovered too late to see perform, the band that came through Phoenix months before I learned about them in 1989, then broke up before they could return. They’d always be the longhaired youths staring at me through the fish-eye lens on their album insert, their faces warped by photography, distant and unreachable. Even in Seattle, they existed in a bubble now, frozen in a golden age when life was simpler, fame still lay ahead of them, and their city was still sleepy. The Love Bone preserved in photos was one who fans throughout the world could cling to as they were at their peak, mythologizing their lives and staying drunk on nostalgia, for their youth, their purity, and for their lost Seattle. No pilgrimage could let me access old Seattle. Yet the city brought certain things to life.

Walking around Pike Place Market, my parents and I climbed a hill and inevitably passed a landmark: the Virginia Inn at 1937 1st Avenue. This is the spot where the characters Steve and Linda drink nothing but water on their failed first date in Singles. As I stood beside it taking it in, it became much more than a set.

The whole pulse of urban life was different in Seattle. The Virginia Inn occupied the corner of an old brick building perched high above Pike Place Market, in a building whose first floor has housed a bar since 1908. Mark and Linda sat in the corner table, right where my parents and I stood, where they could look out the windows at the bustling streets of their city. Phoenix had old brick buildings, but they were few and far between compared to Seattle. We had hills in Phoenix, but not ones with views like this of the snow-capped Olympic Mountains across shimmering Puget Sound. Phoenicians couldn’t walk around our city like my parents and I walked here, and if you did, walks rarely led you through lovely wooded neighborhoods or a vibrant downtown. Phoenix walks led you miles one way down scorching suburban streets, past shopping plazas and office parks full of dentist offices and nail salons, or they trapped you in residential cul-de-sacs as you tried to reach the Circle K convenience store two miles from your house. The Virginia Inn embodied everything I didn’t know I wanted in a city until this moment. Its beauty surpassed its appearance in Singles. It illuminated my city’s limitations and encouraged me to find a place to live that could offer me more. My folks and I had vacationed in San Francisco once, and it was incredible. But more than any city I’d visited, Seattle showed me what a city can offer its residents: density; neighborhoods with neighborhood shops; trees arching over sidewalks; a chance to get rid of your car and rely on your feet, bike, and bus. For a kid in a flat car-dependent city, that was a revelation.

The city looked just like it did in Singles, except the summer weather lightened it: the red sides of old brick buildings chipped and bulging with layers of masonry and moss; the seagulls hovering overhead while huge menacing ravens pecked the sidewalks. Downtown was decorated with Indigenous art and totem poles. People stood in doorways smoking cigarettes and holding coffee cups. Its sophisticated, urban character had nothing to do with its music and everything to do with the natural and urban environment. I’d become to used to hating on my city that I didn’t realize cities could be this easy to love. Seattle was as lush and green as my grandpa Shapiro had described. The air tasted sweet. It was moist, with a twinge of the coast in it, not the heavy exhaust-laden heat of Phoenix. Seeing a band of mist conceal everything excerpt the top of the Olympic mountain range, seeing moisture peel off the tall spires of evergreen trees, a fishing boat passing on the morning water—it enchanted me. This was the antithesis of my desert childhood, and I felt so at home here that I wanted to make a home here. When Andrew Wood sang, “It’s a pretty time of year when the mountains sing out loud,” I knew why he was singing: The landscape’s grandeur felt so holy that you had to try to capture it somehow in art. I tried to sketch it in my notebook. This, I thought, is for me. It must be hard for parents to see their children grow up only to move far away. One day I’d appreciate the way my own ambitions effected my parents emotionally when I moved across the country. For now, I only saw my own experiences.

As my parents and I walked among the summer throngs, we turned a corner and some graffiti caught my eye. It was Mother Love Bone’s name spray-painted on the side of a brick building. My jaw dropped. Was that fake? It seemed hyper-real, like Seattle being the most Seattle version of itself. Those three words held a strange power. Here was Andrew Wood’s voice singing from the dead. Instead of this resembling some staged promotional gesture, the graffiti looked authentic, like some shrine a fan had painted to keep the fallen singer alive. It was an artifact from another time, a voice from what I’d come to understand as Seattle’s sleepier years, left by somehow who was still crying out to the world, “Love Bone lives on!” It was the Grunge version of the “Bird Lives!” graffiti that Bebop fans painted on New York City buildings after jazz legend Charlie Parker died in 1955.

Turns out, we were walking on 1st Avenue passed The Vogue—one of Seattle’s venerable rock clubs. The graffiti looked familiar because it resembled the graffiti that appeared at the beginning of Singles, in a scene where Ruth lets the heartbroken Linda cry on her shoulder outside the real downtown club Re-Bar. Linda and Ruth had gone out for an innocent night of dancing. Being Seattle, Pearl Jam performed “State of Love and Trust” live inside, perpetuating the teenage fantasy that you can hear music that good in a tiny bar any night of the week in Seattle. Over the years, Mother Love Bone’s name had appeared on many downtown walls.

Love Bone bassist Jeff Ament painted the Re-Bar graffiti. He’d created that distinctive font, and director Cameron Crowe used Ament’s font for the credits and fonts in Singles. The graffiti eventually got erased, and The Vogue became a salon. Seattle was growing. But in 2016, an appreciation of the city’s musical past had grown, too, and Love Bone bassist Jeff Ament painted his band’s name back on the side of Easy Street Records, using the same iconic font. Seattle’s ghosts were very much alive.

The graffiti confirmed the presence of greatness. Commodified or not, old Seattle was still here, lurking behind the new condo buildings and new money that Wood’s band helped usher in. He’d left a mark on this city, and here he was singing across the divide from old Seattle to new. Did the new arrivals hear him? I felt connected to that past, even connected to—dare I say it—Wood himself. After years of listening to his voice, a physical embodiment now stood before me. This cold brick was the closest I’d ever get to seeing him perform in person. I walked over and pressed my hand to the brick—like a believer, like a dork.

Emboldened by the encounter, I kept looking for more signs of musical life. Seattle rock legends still walked these streets. I hoped to find them.

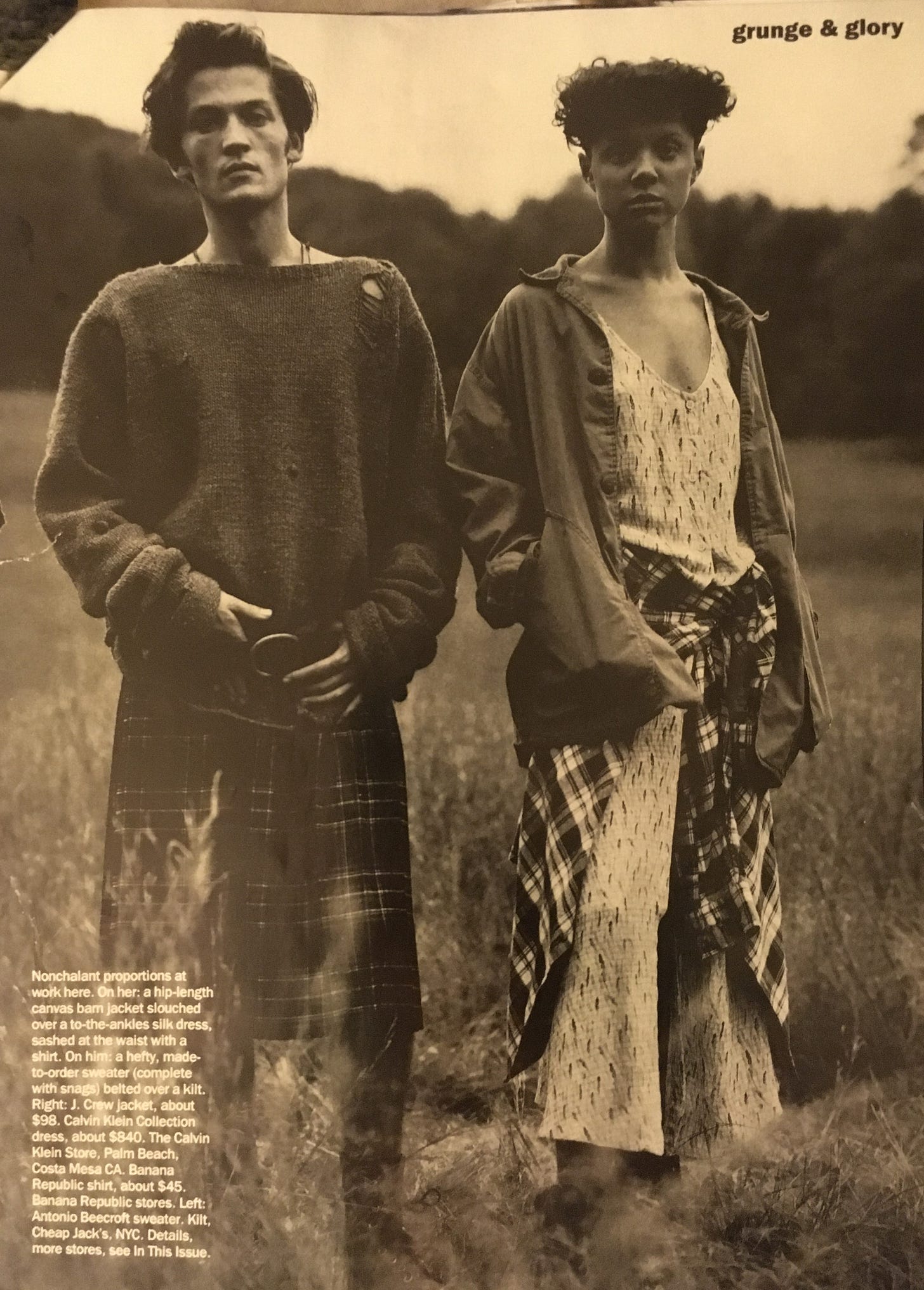

You have to understand. What was a business opportunity for many people was a powerful music experience for young people like me. My friends and I didn’t dress in what mainstream media labeled “Grunge.” We wore flannels and Van’s, thrift store shirts and baggy corduroy pants because we always had. We were skaters turned rock ‘n’ rollers. We didn’t wear thermal underwear under our shorts or big floppy hats like Jeff Ament. We didn’t even say the word Grunge. Obviously, that was lame. But the New York City fashion world briefly embraced the flannels and raggedy ass schematas they saw around here and tried to sell “Grungewear” to America, producing crazy expensive versions of thrift store items and photoshoots in mainstream magazines like Vanity Fair. “Who didn’t get a flannel shirt for Christmas from their relatives?” said Sub Pop’s Megan Jasper in Hype! “And you tie it around your waist and run off and do a stagedive. All across America.” “[T]hat,” said Soundgarden and Alice in Chains manager Susan Silver, “was the only moment for me, so far, that came close to unbearable.” We thought of our music as rock ‘n’ roll. We liked to believe that all that marketing stuff wasn’t for us. The bands we loved happened to hail from Seattle. It was all about music.

But even a mainstream commodity could move consumers emotionally. The 1992 movie Singles did.

It’s hard to imagine a romantic comedy as corny as Singles influencing peoples’ lives, but Cameron Crowe’s movie had a profound effect on many of us ’90s kids.

Crowe had noticed what was happening in Seattle early on. In simplified terms, it happened like this: Seattle’s alt-weekly The Rocket had been celebrating local music in its pages since the late-80s, but it was only when Mudhoney took Sub Pop’s message of Northwest rock to Europe in 1988, and an English journalist named Everett True wrote a story about Seattle music in The Melody Maker in 1989, that profoundly helped Seattle music began to leave the Pacific Northwest. England was into it. Buzz started. Bigger crowds showed for Seattle rock shows. The poppy Young Fresh Fellows broke out of the Seattle bubble first on the independent labeled Pop Llama. And glammy Mother Love Bone were the first local bands to sign to a major label. But it was Nirvana’s big hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit” that truly broke the scene globally in 1991, spreading the gospel along with Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam’s Ten. Of course it wasn’t a straight line from Nirvana to Seattle taking over the world, but you get the gist. Then came Singles in September 1992 to push the gospel further.

As a music journalist, Crowe had his nose to the ground, and people always tip people like that off to new musical developments. Singles started filming in the spring of 1991, and Crowe decided to incorporate Seattle’s emerging rock culture into a fictional story about what Vogue magazine described as “youth in love, in despair.” Pearl Jam had just formed when he started filming, but they hadn’t released any music yet. The timing was perfect. Filming at the beginning of the Grunge era meant he could capture it before it broke.

The plot’s simple: A group of young urbanites are all dating and looking for love. One of those characters is Matt Dillon, who plays the self-absorbed singer Cliff Poncier in a fictional band Citizen Dick. They embodied the look and struggle of aspiring rock bands: day jobs, low wages, cramped apartments, egos, doomed relationships. Although Dillon fronted the band, Pearl Jam members Jeff Ament, Eddie Vedder, and Stone Gossard are his bandmates.

Maybe I was too stoned, or possibly too dense, but the movie confused me. Was this partly a documentary about Seattle bands? Why was this Vedder guy in the movie? I’d just seen Pearl Jam playing in Phoenix in 1991, and now in 1992, they were acting? And my favorite singer Chris Cornell is, like, randomly standing with Cliff Poncier during that scene at the apartment complex, when Cornell wasn’t an actor in any other scene off-stage? I didn’t understand the idea of cameos or an homage, or the gray area where reality and fantasy overlapped. I’d gone to a Catholic high school for the education. What had they taught me? Admittedly, Spinal Tap had confused me, too, freshman year. Things were very cut and dry for me then: Was this real or fake? It took a while to figure out that the film drew from real life enough to blur the line between reality and fiction, and that both could be true. All I knew is that I loved this movie enough to watch it over and over, particularly the concert footage of Soundgarden and Alice in Chains.

Eventually I figured it out. Although only one of Singles’ narrative threads was about music, part of Crowe’s aim was to celebrate bands like Pearl Jam. Crowe dreamed up Citizen Dick for the movie and cast actual Seattle musicians to back him in order to integrate what was happening in Seattle into the romantic comedy. That way Singles could be a rom-com, and a celebration of the music, and make studio execs happy by using the music as ploy to get the young people who were buying alternative music to also buy into this movie.

“I loved Mother Love Bone,” Crowe told Spin in 1991, “so when I was writing the movie that would end up being Singles, I wanted to interview Jeff and Stone to explore the whole coffee-culture, ‘two or three jobs, one of which is your band’ lifestyle. The terrible turn of events that took place was that Andy died. And everybody just instinctively showed up at Kelly [Curtis]’s house that night. For me it was the first real feeling of what it was like to have a hometown—everybody pulling together for some people they really loved. That was a pivotal moment, I think, for a lot of people there. It made me want to do Singles as a love letter to the community that I was really moved by.”

Crowe dressed Dillon in Jeff Ament’s real clothes for authenticity. “I definitely don’t talk like Matt Dillon,” Ament told told Spin in 1991. “But I made a couple of thousand bucks loaning him my clothes. I wore shorts year round. I rode bikes everywhere, didn’t have a car, and if I was going to practice I had to carry my bass on my bicycle, so I couldn’t wear jeans. I’m not sure what defined what grunge was or wasn’t. I never ever wore a flannel shirt. I had a few hats, for sure. That started off when I was in Green River and had a girlfriend who made hats. At the time, I don’t think I looked like a rocker, I looked like a dumbass. It was partly function and partly what was laying around.” Crowe used Ament’s font for the film’s credits. Hollywood’s central casting couldn’t do a more authentic job than that. And Citizen Dick’s big song “Touch Me I’m Dick” was ripped off Mudhoney’s breakout song “Touch Me I’m Sick.” It was brilliant.

“Singles was in the can for a year before it came out,” said Crowe. “But the success of the so-called ‘Seattle sound’ got it released.”

Anyone could see that Singles was corny, but it was corny fun. You could see yourself in it, and the music ruled too hard to dismiss it entirely. It was also great how you could roll your eyes at the story but love the soundtrack, letting us status-conscious teens distance ourselves from the parts that could diminish our cachet. It contained new music from Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Mudhoney, but Chris Cornell’s solo acoustic “Seasons” was my instant favorite. It was haunting. Only after I visited Seattle myself did I realize how much it sounded like the Pacific Northwest felt: ethereal, darkly beautiful, haunting, haunted, and just a bit sad in that welcome kind of way. It put me in touch with my sensitive side in a way that my hard-edged guitar music like “Overblown” did not. I played it, and I cried. The music, not the lyrics, moved me. My love for its strong feelings forced me to see myself more as I was than as I wanted to be: vulnerable, damaged, hurt, soft, and sensitive. Sensitivity scared me. I didn’t want people to see it. I wanted them to think I was tough, with a wild, reckless attitude that intimidated as much as it distracted from the swirling emotions behind them. And speaking of emotions: Mother Love Bone’s “Chloe Dancer / Crown of Thorns” found me again on this soundtrack. It was one of Crowe’s favorite songs, so he used it in two of his films.

Singles was the first time I experienced a soundtrack being as good as any regular album, and it wasn’t the last. (Empire Records tried to recreate that magic in 1995, with a soundtrack by Gin Blossoms and Better Than Ezra, but they couldn’t do it. High Fidelity succeeded in 2000.) I played Singles nonstop. To my surprise, I loved Paul Westerberg’s poppy sing-along “All my life, waitin’ for somebody” song as much as the rockers. I didn’t know who he or the Replacements were until this movie introduced me, and Westerberg’s song defied my perception of myself, challenging my idea of what kind of listener I was, which foretold many such changes in the years to come.

Vogue loved the movie. “Singles can’t be commended too highly,” their review said, calling Crowe’s work “a fine balance of wit and sympathy, and a respect for the quirks for both actors and characters; it’s rare to watch a film in which you follow the story with a kind of delight, thinking, My God They’re Getting It…Right.”

Others hated it. “Crowe’s shallowness is typified by the fact that the redoubtable Sedgwick (Mr. and Mrs. Bridge) plays a bright, concerned ecology crusader who treats her garage-door remote control as her most prized possess,” wrote someone in a clipping whose name I didn’t record. “Crowe’s script relies for humor on such puerile notions as the supposed similarity between the words Spam and sperm, and such dullard’s epigrams as ‘It’s better to be the dumper than the dumpee.’” He hated the music too: “Crowe’s excuse for making this movie would seem to be the flourishing rock-music subculture of Seattle. …None of the bands stound out.” Really? They each sound very different to me. The soundtrack’s eclecticism was part of its charm. As Cliff Poncier would say: I feed on your negative energy.

This was the stuff that filled my head as we walked around Seattle.

I wasn’t expecting it, but when my parents and I walked the waterfront again, I turned my head and there it was: the Java Stop coffee shop from Singles in all its Grunge glory, sitting quietly in the shadow of the towering Viaduct.

I told my folks to hang tight a second as I trotted across the road and peered through the front windows. The counter, the booth where Pearl Jam and Matt Dillon shared coffee—It was all there. My heart raced as I stared through cupped hands. Tons of Grunge tourists visited this for the same reason, whatever that was.

The fictional Java Stop coffee shop sat inside the very real OK Hotel, a popular underground bar and music venue located at 212 Alaskan Way S. under Seattle’s raised highway, called The Viaduct. It ran along the Sound, past Pike Place Market, and faced a narrow parking lot and the waterfront. Singles changed its name to the Java Spot. As Crowe filmed his movie in the spring of 1991, Nirvana played there with Bikini Kill and performed “Smells Like Teen Spirit” live for the first time, the song that would change them and Seattle forever. In 1991, it was still a quiet little spot where everyone from The Gits to Skin Yard to Green River played, which made it the perfect location for Crow’s love letter to Seattle.

The most famous scene that took place there was a conversation between Cliff Poncier and his band, Citizen Dick. They sat at the booths by the front windows, creating a setlist for a show, and debating the dubious merits of encores. Then Jeff Ament pushes a newspaper into the center of the table. “Hey,” he said, “check this out man. A review of our record.” Ament starts to read the harsh review—“When Cliff Poncier starts to sing...”—and Poncier stops him once the review criticizes Poncier’s performance.

They read the review in silence, glossing over the part where the reviewer wishes Poncier would leave Seattle for anywhere else.

Vedder and Ament study Poncier’s face.

“Other than that,” Ament says at the end, “he was ably backed by Stone and Jeff and drummer Eddie Vedder. That’s good. That’s a good review.”

“A compliment for us,” Vedder tells him, stroking his fragile ego, “is a compliment for you.”

Poncier responds by saying that negative energy only makes him stronger, and that their band will not retreat.

“This weekend we rock Portland!”

The band high-fives.

That’s an iconic scene.

Until then I’d played it cool, keeping calm while we explored cinematic Seattle, but peering through that front window, my teen torso tensed and I wanted to scream: They sat right there!!! I would’ve done anything to sit at a table with those guys.

I looked in. I stepped back. What more could I do? That’s all a pilgrimage was: an attempt to extend the power of the music to something more than it can ever be, to get to know the art more intimately, to find a physical locus for what only exists in the air and the heart, to touch, as Sam Cooke sang, “the hem of his garment.” Once I had, it thrilled and disappointed me, because it couldn’t give me anymore, so I strutted back across the street to my parents, playing it cool, as I always tried to.

No matter how commodified Seattle was, the place was special.

I didn’t have much ambition in those days. I made plans without following through, so I never made a map of the holy sites I wanted to visit, and I made no list of locations to check off upon completion. Whatever happened happened. That meant few things happened. Leaving my pilgrimage to chance meant that I missed the alley where Pearl Jam shared their first rehearsal space with Eddie Vedder in 1991. I never saw the apartment where Chris Cornell and Andrew Wood lived together and wrote haunting songs like “Island of Summer” together. Never saw the Coryell Court apartment building at 1820 E. Thomas Ave where Singles characters lived, either, or the site of the old Off Ramp Café where Pearl Jam played their first show. If we passed the Paramount Theatre, I didn’t notice.

My folks and I rode to the top of the Space Needle. We rode the monorail to downtown, pointless as that short trip was. And we made important discoveries that summer that carried over to the rest of my life. We got take-out from a small Italian deli at Pike Place and ate it in a park overlooking the Sound, and I came back to that deli to repeat the ritual every time I visited Seattle for at least a decade. My sentimental attachments bordered on eccentric, but that’s how I was: not a creature of habit as much as a creature of heart, and my heart affixed itself to certain places with the strength of a barnacle.

Although I regret not seeing any bands play or peeling concert flyers off of power lines in 1994, I did grab a copy of The Rocket. The Rocket was the shit, as we said back in the day, and it would always be the shit. It wasn’t distributed far outside of Seattle, so we never saw it in Arizona, but because national music magazines sometimes referenced The Rocket, I knew what it was. So I grabbed an issue from a rack somewhere, not only as a souvenir but as a talisman of my coolness, a symbol that I knew what was up and had visited the holy land. Bringing back a copy of The Rocket was like carrying Medusa’s severed head out of a cave: I went into the belly of the beast and returned triumphant and transformed! I still have that copy. The most profound moment was also the quietest.

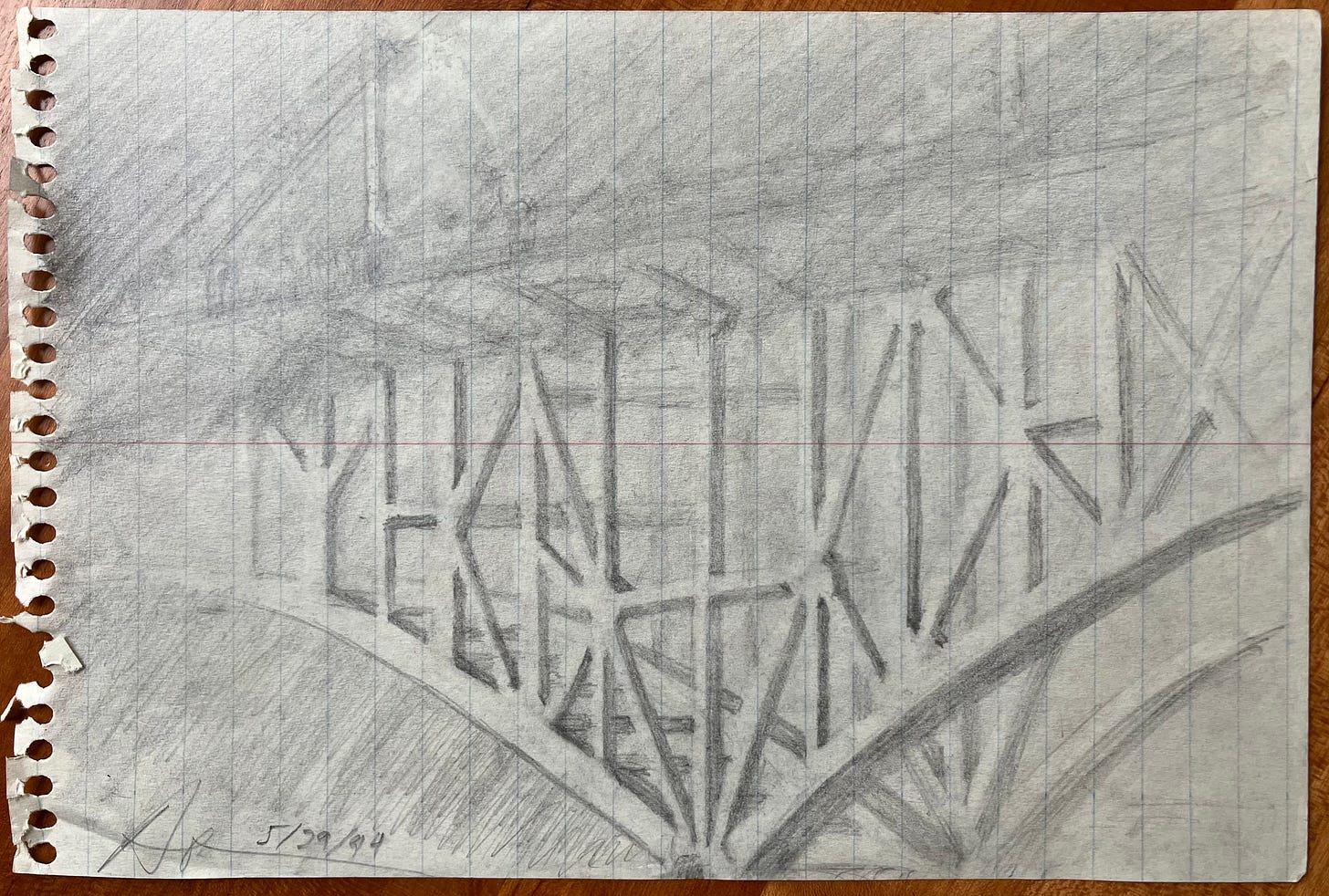

One night I took a solitary walk. Our hotel stood on Aurora Ave overlooking Lake Union, where floatplanes landed and people lived in houseboats docked along the shore. Two bridges cross the Lake going north to south, and I left my parents at the hotel to walk to the bridges. Instead of getting stoned, as I would have had I been able to bring any weed, I sat under the Aurora Bridge and did what had brought me joy for years before I discovered drugs: I drew. The metal structure that connected the bridge to the hillside made a beautiful arch, and I tried to capture the way the straight beams interacted with the curved beams, and how it all hovered, partially illuminated, in the moist darkness. It was beautiful. The water lapped below me. Cars passed overhead. I actually liked how my drawing turned out—its play of light and dark—and I kept the drawing ever since.

The drawing now seems symbolic—a bridge between my Arizona past and my Northwest future—because something had permanently changed. My sense of identity shifted beyond what it had always been: a desert kid. I returned home a different person: one with more agency, one with a vision of his future self, one who could finally say he knew what he wanted, and this Northwest life was it. I took this drawing of Seattle home with me, and I vowed to move up there when I could.

I returned home with a greater sense of place, too. Grunge taught me geography: I knew where Seattle stood on the Puget Sound. I knew where Aberdeen (Nirvana’s town) sat in relation to Tacoma (Girl Trouble’s hometown) in relation to Ellensburg, Washington (Screaming Trees) and Bellingham (Estrus Records HQ), and I knew where the Puget Sound was in relation to Mt. Rainier and the Olympic Peninsula. Who knew rock ‘n’ roll could provide such a detailed topographical lesson?

Returning to college in Phoenix after that trip was difficult. Once I tasted the Fruit of Knowledge, my old desert garden seemed barren and boring. College became a waiting game. I had to do my time in order get out of Arizona and to where I felt I belonged.

Once I graduated from college in 2000, I moved to Portland, Oregon, which was a better choice at the time, because it was cheaper than Seattle, and I got a job there first. I’ve been up here for 21 years.

After two decades living in the Northwest, I’ve seen a ton of shows, seen a lot more of Seattle, and I’ve planted the kind of roots that make it truly home. I even filmed a band play the Crocodile Café. When I visit Seattle now, and the moisture hangs low over Puget Sound and rain darkens the red brick walls, it’s like facing the early 90s Seattle I first got to know. The old Northwest energy isn’t all gone. I still see the places that I first saw when I visited, like the Virginia Inn above Pike Place Market, and sometimes I get glimpses of the Seattle that existed before Singles, the Seattle before Capitol Hill filled with shiny, cheap-looking apartment buildings and downtown became the domain of the rich, a time when Ivar’s cedar plank salmon could seem like a special meal.

In the summer of 2019, I took my own two-year-old daughter to see the troll under the Fremont Bridge. We watched musicians play on the street, we made a pilgrimage to the Tractor Tavern—where so many legendary Northwest bands played—and we drove passed the Viaduct where the OK Hotel once hosted The Gits and Nirvana. I still loved music, still loved Seattle, but I loved being a dad now more than I loved being young and solo.

The circle of life is complete.

I still religiously wear striped shirts.

1996 was probably the peak of alternative music. It lost currency after that.

During those mid-90s years, people complained that Seattle had lost its soul, that wannabes had overrun it, and real estate people were gobbling up all the property, risking making the cost of living too high for the kind of musicians who defined it. As Mudhoney sang: “Everybody loves us / Everybody loves our town / That’s why I’m thinkin’ lately / Don’t believe in it now. It’s so overblown!” From my home in Arizona, I mourned for Seattle. That sucks that people are ruining it, I thought. No one liked my town enough to ruin it, but I would’ve been mad if they did. Lame tagalong bands like Stone Temple Pilots and Candlebox were ruining music in general for me, aping peoples’ style and making their watered down version the standard. Andrew Wood’s lyrics about himself now applied to a booming Seattle: “He who rides the pony must someday fall.”

On May 17, 2017, a few months after my last Seattle trip, Soundgarden singer Chris Cornell took his own life. He was 52 years old. His voice defined my early-90s. His voice was inseparable from Seattle. He’d outlived his friend Andrew Wood and even co-written a whole album, Temple of the Dog, memorializing his fallen friend. The two were so close that Wood’s family had waited to take him off life support in order to give Cornell time to fly home from New York to say goodbye. Why end his own life now? Fans were confused. He and Vedder always seemed to be the gentle, caring, stable ones. They did philanthropic work. Cornell had kids. He was in the middle of touring. Soundgarden had finally started recording a new album. Why had he done this? Why does anybody?

After Cornell’s death, a music promoter named Eric Alper tweeted: “The voices I grew up with: Andy Wood Layne Staley Chris Cornell Kurt Cobain…only Eddie Vedder is left. Let that sink in.” The Chicago Tribune echoed that sentiment: “Vedder, the frontman of Pearl Jam, is one of the movement’s only icons who is still alive.” First of all, it wasn’t “a movement.” They weren’t organizing to dismantle systematic racism or push a social agenda. They were musicians united by location and a love of loud guitars. Second, other Seattle icons survived: What about Mudhoney singer Mark Arm? His first band Green River predated Soundgarden and set the stage for all that came after. And what about Sub Pop engineer Jack Endino? He recorded most of Grunge’s iconic albums. Hell, he was the guy who first recorded Nirvana and tipped Sub Pop off to the band’s existence. Endino was alive and well. So was L7, Tad, Screaming Trees, and Sub Pop’s co-founders. Arm still managed the shipping department at Sub Pop headquarters, the label that his band helped make, and Mudhoney still toured. Somehow, despite Mudhoney’s stage energy and beery off-stage antics, Arm was always one of the most stable in the scene. In 2018, Arm got me into a sold-out Mudhoney show so I could see the Australian band The Scientists open. The Scientists had influenced Mudhoney but never played the States before, and Arm generously hooked me up so I could finally see them in action—me, just a fan who couldn’t get tickets fast enough. Over the years, Seattle icons have been incredible kind and generous with their time with fans like me. I’ve talked with Endino on social media about an unreleased Cat Butt album. I’ve talked with K Records founder Calvin Johnson at a show. I’ve house sat for Young Fresh Fellows’ singer Scott McCaughy, emailed with Bruce Pavitt and Steve Fisk about pre-Grunge bands like The Macs. And Dead Moon bassist Toody Cole even held my daughter in a record store.

To call Cornell and Vedder the last true icons is unfair to all the talent that built the Northwest’s musical reputation. But the sentiment was right: Cornell’s death marked the end of something bigger than Seattle, just as Cobain’s suicide had in 1994, and for middle-aged fans, that stung. When certain voices define your youth, their loss is personal. This was our music, and it had suddenly ended before we could prepare ourselves. Fans got no warning of illness, no reason to brace ourselves. Just boom: No more Cornell. No more Soundgarden. In mourning Cornell, we were also mourning the death of our youth.

The Chicago Tribune wrote about all the people tweeting how Grunge was dead:

Lisa Urich tweeted: “Eddie Vedder just became the Betty White of grunge.”

Rebecca Barrows tweeted: “Eddie Vedder is basically a National Treasure at this point. We have to protect him at all cost!”

Navendu Jha tweeted: “#KurtCobain, #LayneStaley and now #ChrisCornell :/ Legends of #Grunge #RestInPeace. Somebody please bubble-wrap #EddieVedder. Please.”

The Iron Sheik tweeted: “I PROTECT THE LEGEND EDDIE VEDDER FOREVER”

Matthew Inman tweeted: “Seattle: let’s build a moat around Eddie Vedder.”

Cav Empty tweeted: “Eddie Vedder the last Jedi”

In youth we awaken to music. Music later lays us to sleep. We all grey. Our smooth skin wrinkles. But when the rock gods of our teens start to die, our own death becomes palpable. Some of us will live on in other ways.

Beside the words Mother Love Bone on a wall in Seattle, someone painted “Chris Cornell.” One day a kid will walk by that and feel connected to them, too, just as I had. And one day, another fan will paint over it with the names of a new generation’s sounds.

What’s amazing is the way music maintains its power across so many decades. Hey Seattle: Thank you.

Andy was alive and well when the original mural was painted along first avenue, the vogue came later…