Modest Mouse and the End of the 1990s

The Washington band's third album arrived to me in Arizona during my darkest time, comforting me like an emissary from the Pacific Northwest, where I was determined to move to start fresh.

In the motions and the things that you say

It all will fall, fall right into place

—“Gravity Rides Everything”

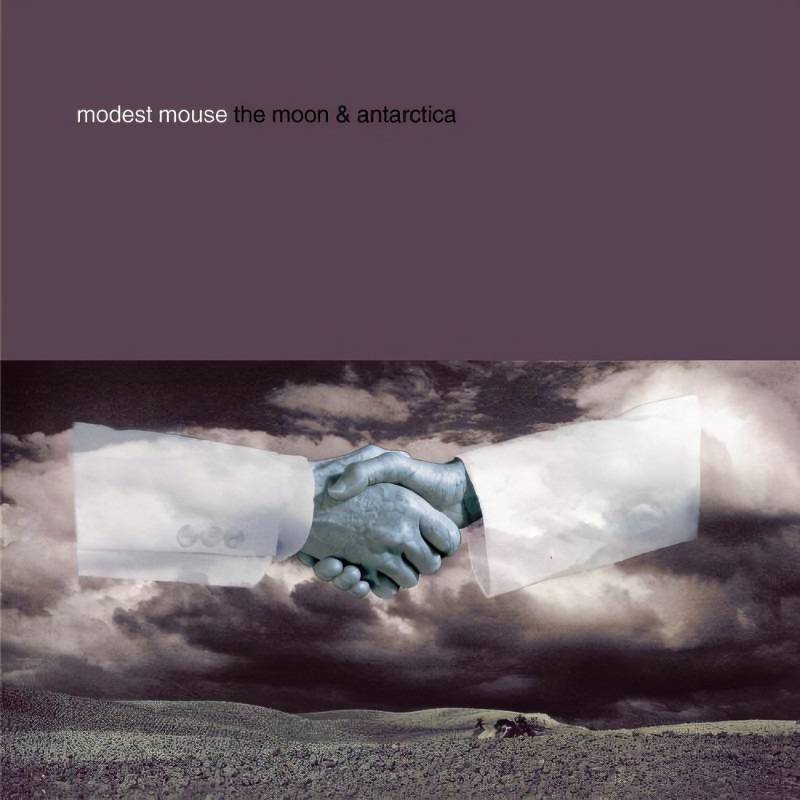

Modest Mouse’s third studio album, The Moon & Antarctica, will always remind me of the most depressing summer of my life and how, when I couldn’t take it anymore—the loneliness, the listlessness, the depression after getting dumped and getting sober at age 24—I permanently left my native Arizona for Oregon. The Moon & Antarctica was my album of transition, exerting a feeling of eternal winter on a soul that was used to permanent summer. Fittingly, after spending months listening to this album, Modest Mouse was the last concert I saw before moving to the Pacific Northwest, two days after the show. That show marked the night when my 1990s truly ended.

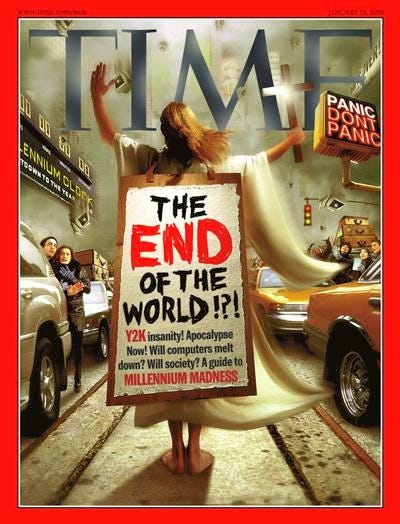

December 31, 1999 was an important New Year’s Eve. The ’90s and the 20th century were ending simultaneously, and many people thought the world would end with them. In the preceding months, New Year’s got nicknamed Y2K. Y2K was shorthand for a potential worldwide computer programming glitch that many people believed would wreak havoc on everything from utilities to banking to healthcare—anything involving microchips. The way computers formatted numerical calendar data was flawed, so if computers got confused when the date turned from 1999 to 2000, it might cause a global systemic collapse resulting in food and gas shortages and power outages.

Y2K predictions included airplanes falling from the sky and elevators dropping down shafts as the world’s financial systems crashed and government records got scrambled and released. Practical people stockpiled supplies. Others stockpiled weapons and bought Y2K insurance. Conspiratorial types braced for disaster. Some welcomed it. “The Rev. Jerry Falwell suggested that Y2K would be the confirmation of Christian prophecy,” The New York Times reported in 1999, “God’s instrument to shake this nation, to humble this nation. The Y2K crisis might incite a worldwide revival that would lead to the rapture of the church.” And yet, the ’90s ended with the proverbial whimper instead of a bang. The clock ticked—because we used clocks before smartphones—and that was that.

Like countless twenty-somethings, we threw a party. My fiancé Kari’s parents went out of town, so her and her younger sister’s friends gathered at their house, drinking cheap beer and wine around their backyard pool among the old orange trees.

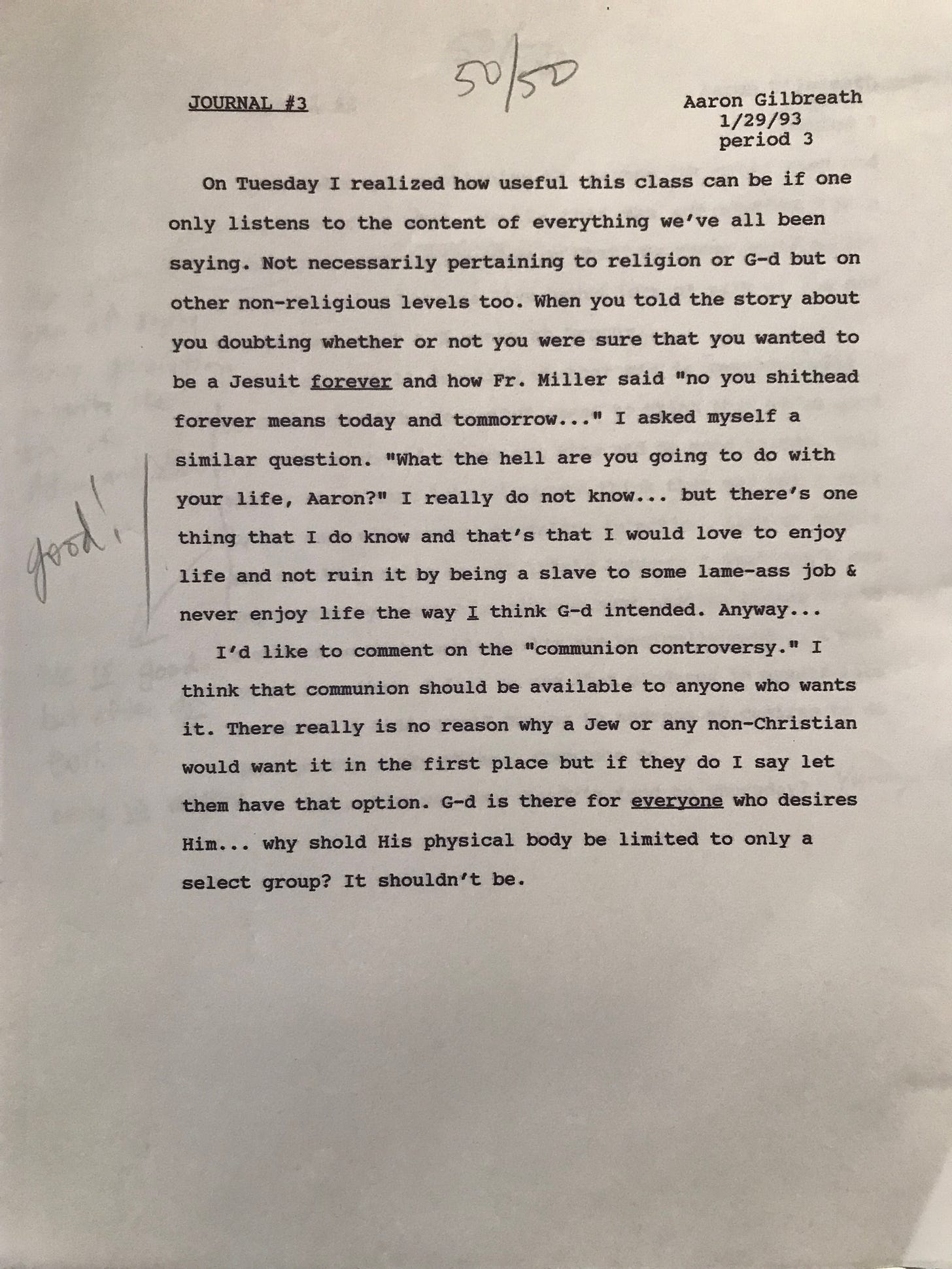

NYE was always a drunken affair. My crew used to find huge parties. At one party someone tossed a VW Bug engine in a backyard bonfire, and it shot blue liquid metal into the crowd of onlookers. This was different. Unlike your dime-a-dozen calendar year, the changing century offered fresh opportunities and obvious symbolism: a new century, a new beginning. What would the future hold? Futures were the main thing on my mind at age 24: specifically, what was I going to do with mine? I’d been wondering since my high school senior year. In my period three English class of Jesuit school, my Jewish ass even wrote a journal entry about it as part of our weekly journal entry assignment, where students reflected on readings, class discussion, and life. I recently found this assignment while digging through old notebooks, trying to understand the course of my life:

In 1999, we young party people laughed at the end times predictions. As midnight approached, we looked up for falling planes and counted down: three, two, one, happy New Year! Nothing exploded. No markets crashed. That was disappointing. I wanted the old world to end. It already felt dead—my drugs, my city, my aimlessness purgatory, where I struggled not to back-slide into old habits but somehow failed to move forward either. I was sick of treading water. Let the world explode, I thought. I need to build a new one.

Kari sipped her wine from one of her parent’s glasses, growing sloppier by the hour, and I knew she’d eventually crawl into the bed in her childhood bedroom. It was the room she would eventually move back into after she broke up with me that summer and moved out of our apartment. Watching her that night made me sad. We were doomed.

Although we’d known each other since high school, we’d reconnected in college down in Tucson and had fallen in love. I did love her deeply. Love was the only reason I’d agreed to move from my beloved Tucson back to Phoenix with her. I moved under one condition: that we’d only stay in Phoenix for the year it would take her to get her Montessori teaching certificate. We planned to move to the Northwest after that. I’d planned to move up there since first visiting Seattle in 1994, which was the year before I left Phoenix for Tucson and vowed never to live in Phoenix again. I didn’t like my native city. Phoenix didn’t have an habitable city center. It didn’t have the creative heat of a big city like Seattle or San Francisco. And the sprawling, car-dependent layout didn’t offer the same urbane energy that the dense, walkable, West Coast cities seemed to. Kari knew I no longer belonged here, but her certification only required one year, and I could handle a year. It only took a year for us to finally fall apart.

I watched her laugh into her wine and knew I was moving north with or without her. She said she wanted to go, but I doubted her commitment. She felt at home in Arizona. Her best friends and family lived here. She was connected. I was adrift. When she’d moved to Eugene, Oregon for college freshman year, she got so homesick that she moved home after her first quarter. Why would she want to move north again? Especially with our dissolving relationship? Neither of us could say the truth out loud yet, and as Soundgarden sang in 1989: “You hide your eyes, but the ugly truth just loves to give it away.”

Happy New Year! everyone yelled as we gave each other hugs. Happy New Year!

1999: Fuck off.

We’d moved from our sunny historic Tucson apartment with wood floors into a depressingly bland, carpeted Phoenix apartment, and to cope with my unhappiness, I kept secretly snorting heroin. After managing a while without drugs or alcohol, I’d relapsed back in Tucson and hid my heroin habit from Kari as I willingly locked myself into daily use. I was a liar and an addict, ashamed to admit how much I struggled not to use drugs despite my fundamental desire to live clean, ashamed how my intense engagement with life collided with my avoidance of uncomfortable things. I felt like a total piece of shit. My self-loathing and our Phoenix location mixed with the guilt I felt from violating Kari’s trust, and it all made me want to numb out more. Then a cop popped me buying heroin in south Phoenix during the summer, and I got put on probation.

I spent 12 hours in jail downtown. When Kari picked me up from jail the next morning, I lied about why: They found weed that wasn’t mine! This was a lame story. The true story was that the cop made me spit out the heroin balloons I’d hidden under my tongue, and this arrest was exactly what I needed. I actually thanked the police officer from the back of her squad car: This is exactly what I need, thank you. And yet, I hid my probation from Kari, my parents, and what was left of my old friends. Because of disinterest and addiction, I’d failed to graduate from college in Tucson, so I walked in the graduation ceremony and took a class at the university in Phoenix to complete my remaining requirements. Because I wanted to be a professional writer and felt traces of my old ambition, I took some elective creative writing courses there, too. I really wanted to learn how to do this. I ended up ditching those classes because I was too depressed to commit. Dreaming was easy. Working was hard. Staying off heroin was harder. I loved heroin. I didn’t like what it did to my life, but I loved how it made me feel, how it took away my fear of the future and replaced the hard work of disciplined creativity with the illusion of inspiration. But those heroin days had to end. The time had come to create my future rather than ruin it. My brain was a mess. New Year’s offered an easy ceremony to mark this new beginning.

Fireworks exploded around the city, and people fired guns into forbidden urban airspace. For me, this New Years was a test of my newfound sobriety. Everyone in this backyard drank except me. The terms of my probation were clear: To get my felony charge expunged and avoid jail time, I had to attend a drug group, and I had to pee clean for one year. To do so, I couldn’t even be around people using drugs, because if they got popped, I got popped by association. When someone lit a joint in the car I was riding in once, I hung my head out the window so not to inhale any smoke. If the piss test detected any THC in me, I went to jail. I refused to go to jail. So while people held their beers in Kari’s parents’ backyard, I stayed hydrated with fizzy water and amped on iced tea. And my friend Lee, who’d also had a heroin habit, stood beside me on the pool deck, waxing nostalgically about the heroin we both missed doing.

“Dude,” he said, engulfing me in beer breath, “if he had some brown, we could talk about anything for hours, anything. And it would be genius.” His ex-girlfriend, who everyone loved, had overdosed in her childhood bedroom a few years earlier, the first of two friends who would die from dope. Yet he struggled to break free of it. I didn’t disagree with him. I would have loved to snort that potent Mexican brown tar heroin again. And again and again. But we had to accept our spot on the arc of the Jane’s Addiction song, “Three Days”: “At this moment / You should be with us / Feeling like we do / Like you love to / But never will again.”

Never.

Like my arrest and addiction, no one knew that I’d gotten on methadone after my arrest. I’d sweated through heroin withdrawal twice before, three times if you count the sweats in jail. Now that I needed to get clean quickly for probation, I couldn’t stand the idea of experiencing that hell again. I was too strung out. So I got on methadone at a reputable clinic near downtown, and I had to drive to get dosed every day before sunrise. Seeing the sunrise over my sleeping city proved to be as healing as the medication. The routine was good for me. I needed the discipline. And I needed to get back in touch with the magic of the world, which I had known so intimately as an undergrad in Tucson while hiking and camping constantly. So every morning while Kari slept, I stepped out of our apartment into the dark pre-dawn world, driving those quiet familiar streets while most houses still had their lights off, I got my dose, and I parked in the darkness near home to listen to music in my car as the first rays of sunlight rose from the east. It was magic. I needed magic that didn’t go up my nose. When Kari asked about this new routine, I did what I’d gotten used to doing and lied, telling her that I went to coffee shops to write before dawn because I felt inspired and needed the discipline. See why I felt like a piece of shit? I don’t know what she believed, but she never pushed for details, and she never challenged me. I do know that we both needed to believe our own reality, but the lying was a habit I needed to break.

According to the clinic, alcohol interfered with methadone, so they advised I abstain. But more than anything, drinking interfered with my life goal: To learn to exist with my head clear, without avoiding uncomfortable things with chemicals.

As Lee went on and on about how much he missed getting high, I tried to change the subject. Instead, I could only pass the time till everyone went home. The next morning, I awoke in a new century with a clear head and a mug of green tea. Kari woke up with a wine headache and a coffee. It seemed symbolic: leaving my intoxicated ’90s youth to begin the rest of my productive adult life. Hindsight makes everything symbolic.

Sure, I relapsed in 2000—snorting heroin and smoking weed for a few weeks—but unlike many musicians from the druggy ’90s, like Bradley Nowell and Kurt Cobain, I entered the 21st century without being a casualty. The numerical ’90s ended on New Year’s, but life is more than numbers. My ’90s came apart in pieces.

Although the calendar had changed, the first months of 2000 felt like the previous months. Nothing was different: not popular music, not the baggy style of clothes, not TV or technology or the pace of my limp life. Friends and Frazier played every week. Bath & Body Works still ruled the malls where we hung out on weekends. Sublime’s “Santeria” still played constantly on MTV and the radio. Lollapalooza had ended by 1998, but Vans Warped Tour still brought horrible ska-punk bands to town, with their vacuous choruses, neck tattoos, and white socks pulled up to the bottom of their long shorts. It was an ugly time for popular music. No wonder I looked to the Northwest for musical innovation. They had K Records, Kill Rock Stars, and Sub Pop. 2000 also felt like 1999 because I was still flailing, but my listening habits totally shifted to the old and new bands that came from up north: Beat Happening (Olympia, Washington), Sleater-Kinney (also from Olympia), Satan’s Pilgrims (a surf band from Eugene, Oregon), The Wipers (Portland, Oregon), The Fastbacks, Dickless, The Gits, Young Fresh Fellows (“Low Beat!”), Green River from the pre-Grunge Seattle, and some killer live Pearl Jam pirate radio broadcasts I’d found on a bootleg CD.

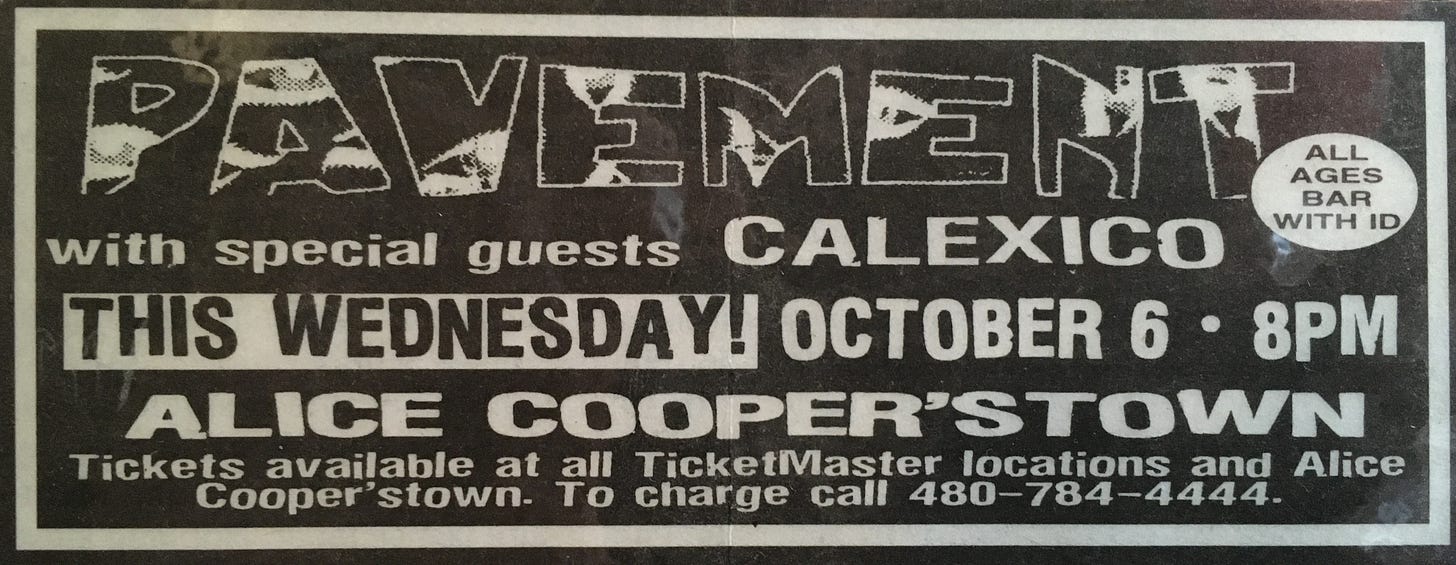

My ’90s started when I first heard Jane’s Addiction and Mother Love Bone in 1989. And my ’90s ended in October, 1999, when Calexico opened for Pavement in downtown Phoenix, not as a two-piece but as a full band, taking the sound that I’d love while living in Tucson with them. Technically, that show was the last show I saw in the ’90s, and it felt like the end of something.

Then again, the ’90s also ended the night I saw The Ziggens play a tiny bar in southern California, four years after their friends in Sublime disbanded and became ’90s music legends. I filmed that show, too.

My ’90s also ended when I discovered Sleater-Kinney’s 1999 album The Hot Rock. That album had more heat than any album I’d heard in years, so it became my new addiction. Calexico and Sleater-Kinney represented opposite poles during a time when I felt pulled in opposite directions. One band hailed from Arizona. One hailed from the Northwest. One pole represented my childhood, my past, my struggle with sobriety; one represented adulthood, clarity, and the future. The fact that Sleater-Kinney lived halfway between Portland and Seattle only confirmed the wisdom of my decision to move to the Northwest: If music this powerful came from this region, I belonged there. Never mind that the Meat Puppets wrote some of the most original, transportive music right near my house in Phoenix. I would only see that later. For now, I needed out.

Kari’s and my relationship limped along through the winter and spring toward its inevitable, necessary end. My gaze stayed fixed on creating my destiny as a writer up north.

On one of the summer’s indistinguishable weekdays, Kari walked into our apartment holding two bags of groceries. “Still there, huh?” She stepped around my spot on the living room floor, dropping the bags on the kitchen counter with an intentional, irritated thud.

“Been working on this essay for Sierra magazine’s contest,” I said, awaiting the applause.

Heavy paper crinkled from behind the wall.

Unshowered and unshaven, dressed only in boxers with a chest licked with sweat, I sat still as a yoga instructor: back straight, legs outstretched, forming a V. The California atlas sprawled before me, the routes of my four previous Central Valley roadtrips outlined and dated in thick black ink. Beside it, a ringed notebook filled with journal entries and drafts of “What if John Muir Had Fallen in Love With the Central Valley Instead of the Sierras?” If I could win this contest, I thought Kari and my parents would see that I was serious about this writing thing, and that it was a viable career choice. Winning this contest would also validate my own uneasiness with my ambitions, and it would provide some sign from the universe that this tenuous impractical thing was worth pursuing. I’d only shown Kari that my writing ambitions were a half-assed, impractical pipe dream because, after two weeks of work, I never submitted this essay. Like all the essays I started and never finished, this one stayed frozen in perpetual draft, all unfulfilled promise with no definite direction and only scattered hints of beauty—like me. Who cares about what could have been? I thought. All that matters is what was.

“How was work?”

“Tiring,” Kari said. “But good.” Teaching rambunctious school kids was always tiring, and she spent her days spent working toward the relief of nighttime TV. “I’d like you to come in soon and give an ecology lesson,” she said.

“That would be fun.”

Kari slid onto the couch and lifted the remote. I put on my headphones, listening to Calexico sing: “Slip away the night/While the whole town’s asleep/Caught between the space/Where you wanted to be.”

This was how we lived our nights.

Among all my books about Southwestern ecology stood a picture frame made of Northwest Indigenous designs. I had one foot in, and one foot out.

Neither of us were happy—not with life, not with each other. After work she would sprawl on the couch and watch Friends and Jay Leno, drinking wine or doing stretches, and I would sit on the floor in front of our living room stereo and listen to The Hot Rock, Girl Trouble, and Pearl Jam’s pirate radio broadcasts on my headphones, dreaming of the future.

Even though we’d driven from Seattle back to Tucson together on a summer road trip in 1997, Kari didn’t understand why I wanted to move to the Northwest so badly. Sure, the greenery was beautiful, and all that water, but we didn’t know anyone there. It was so far away. Mostly she thought I was chasing the old music. Kurt Cobain took his life in April 1994. Soundgarden broke up in April 1997. Pearl Jam still toured, but I hadn’t seen them play since 1993.

“That’s all over,” she told me one night from the couch. “Nirvana, Soundgarden, that whole thing ended years ago. What do you expect to find?”

I didn’t expect to walk back in time to the early ’90s, I explained. I just wanted to live in a region that could produce such a thriving musical world as the Northwest did. I didn’t want those bands. I wanted to join a creative community in a progressive, rebellious region. I wanted to inhabit a landscape that inspired awe in me, the way the desert had in years past but no longer did, a place that could move me to create powerful things, too. I wanted a drastic change in surroundings to help furnish the drastic change in direction I planned for myself. I wanted a city that felt like a city—concentrated, not diffuse—a place that encouraged walking rather than driving and where people could talk and bump into each other and exchange ideas, a place cheap enough to support an aspiring writer, a place where you could make a living working at a bookstore, a place whose underground culture remained rich and encouraging. I didn’t want bands. I wanted energy.

She wanted to stay where it was familiar. I respected that even while I rejected that. Moving excited and scared me, and with fear came hope. Change was an adventure and opportunity. It demanded I rise to the occasion. Here where everything was familiar, location encouraged me to do what I’d always done. I wanted to break my routine and see what new people brought to my life. I loved being scared and excited.

Sitting in front of the stereo, I said that I wasn’t looking to relive the early ’90s. I was looking to create my own version of it with writing. She sat in front of the TV and listened.

When I watched TV, I watched Frazier and the Hype! documentary because they, like my mind, were set in Seattle.

We would never understand each other.

One night she broke up with me at a sushi restaurant. “I love you,” she said, “but I’m not in love with you.” She was braver than me. Like everything else in life, I couldn’t even say the words that we both needed to say. I couldn’t finish an essay. I couldn’t attend class. I could say it’s over. One day she and her mom carried boxes of her clothes and dishes from our apartment, and a few pieces of furniture. I spent the rest of the summer alone in there with the TV off and our cats running around, our cats who were now mine.

I felt more alone than I ever have.

Even when you need to break up with someone, it hurts to be apart.

Apart, my city became even more desolate. Stuck in a city I never meant to return to, I questioned everything’s meaning, especially my connections to old friends and family and this place. I had no place to go but up. Then I found the soundtrack to my summer misery.

There are no photos from the summer of 2000, because there were few people around to take them, and there was nothing noteworthy to capture. You don’t record sadness. You ignore it, endure it, move through it. I wasn’t sure I could.

Lee wasn’t the only one who missed heroin. I wanted so badly to be high, all painless and dreamy. I could smell the heroin in my memory, could feel the sour burn hanging like a gathering raindrop in my nose after I’d snort it, lingering before draining down my inflamed throat. That Thai dressing smell, that caramel bile mixed with melted plastic and engine fluids. Every day I thought about heroin. Every day I resisted using. And I sat with my struggle in my lonely apartment, hoping that by moving away, I could strengthen my resolve. Until then, I just felt lonely. Being lonely and depressed made me want to get high. Methadone helped me resist the urge. And methadone bought me the time for my brain to repair itself.

Alone in my apartment, I listened to Calexico’s first album Spoke on my Sony Discman—trying to conjure the good feelings I’d had while living in Tucson with this album, wondering if I should just move back there instead of north—and I cleaned parts of the kitchen where Kari’s mugs used to sit. The cats ran by—our cats, my cats. In place of photos, I only have memories—fleeting impressions that still circulate through my mind two decades later. And I have the footage I shot of Modest Mouse performing on The Moon & Antarctica tour.

After reminiscing about heroin that New Year’s Eve, Lee and I hung out a lot back then, sharing music, trying to stay clean. One day we were riding in my truck and Sublime’s “Santeria” came on the radio. “Shut that shit up,” he said, nearly smashing the stereo’s off button. “I’ve heard that song too much.” Soon after, he played me Modest Mouse. I’d never heard of them.

They had just released their third studio album, The Moon & Antarctica, that June, and Lee was obsessed with it. Inside his dim cinderblock apartment, he played it for me. He had to get to work at his rental car job, but we had time to listen and drink caffeinated soda. With the cheap curtains blocked the blinding desert sun, the apartment turned dark, and the first words that came from the singer’s mouth resonated so deeply that it felt like he was singing directly to me:

Everything that keeps me together is falling apart / I’ve got this thing that I consider my only art / Of fucking people over.

The album began where I began: acknowledging my unraveling, my artistic ambitions, how I’d betrayed Kari and myself, and how that was all connected.

That first song, “3rd Planet,” grabbed me immediately. When singer Isaac Brock sang “And that’s how the world began / And that’s how the world will end,” this became my album.

Music is the language for what we can’t say, and when singers say certain things, they often speak clearly about life by speaking indirectly. As the singer of The Flaming Lips said about their 1999 album, The Soft Bulletin: “It goes into the realm of just unspeakable things. And that’s why we have music and images, because there’s, like, these cracks in our reasoning that we just can’t speak about it.”

The first two songs on The Moon & Antarctica were slow and sad like me, but they were threaded with intensity. Modest Mouse’s music had a different rhythmical sensibility than other heavy bands I listened to. The music was dark, strange, sometimes scary, and combined with Brock’s opaque lyrics, it registered as a kind of chilling existentialism, packed with as much wisdom as confusion and questions. Brock’s singing was like no other: feral, sad, intense, pained yet controlled.

The second song, “Gravity Rides Everything,” became the centerpiece of my sadness, the song I played on repeat, the song that ruined me on the album for a decade. In it Brock sang:

Oh gotta see, gotta know right now

What’s that riding on your everything?

It isn’t anything at allOh gotta see, gotta know right now

What’s that writing on your shelf?

In the bathrooms and the bad motelsNo one really cared for it at all

Oh, I thought, what’s this one about: Nihilism? Depression? A sense of despair about the meaninglessness of it all?

I mouthed Wow to Lee as we nodded our heads in his living room. In youth, music was always relational. It was something we friends shared, in cars and bedrooms and at concerts together. Lately I carried too many things on my own, hidden and private. It felt good to share this with him.

“See?” Lee said. “I told you it’s fucking amazing!”

We kept listening:

Early, early in the morning

It pulls all on down my sore feet

I wanna go back to sleep

I did, too. But I needed to wake up.

As Brock sang, a guitar came in, tracing the space behind his voice: a clean assured guitar sound, with bending strings and the kind of ethereal twang I loved in surf music and The Smiths.

In the motions and the things that you say

It all will fall, fall right into place

As fruit drops, flesh it sags

Everything will fall right into place

Like the best lyrics, certain lines where vague enough to apply to my situation. His line “It will all fall right into place” felt encouraging, suggesting that no matter how dark and uncertain life felt now, I’d look back at this period one day from the other side. In the coming weeks, I sang that line out loud in my car and in my lonely apartment: “It all will fall, fall right into place.” But would it? Says who? I sang to make it true. Yet overall, a few optimistic words couldn’t reverse the song’s desultory mood.

When we die, some sink and some lay

But at least I don’t see you float away

I felt magic in this, a magic I needed to feel to feel anything good at all. I loved the way heroin numbed everything out, but “Gravity Rides Everything” reminded me why I had loved feeling things intensely so much more, even uncomfortable things. Numbness wasn’t living. It was dying. Feeling this much was living. I came awake again.

It didn’t stop at “Gravity.” Other songs slayed me upon first listen: “Dark Center of the Universe,” “Perfect Disguise,” “Tiny Cities Made of Ashes,” “A Different City,” “Alone Down There,” “Paper Thing Walls,” and “What People Are Made of.”

Brock wrestled with relationships, morality, trust, and his own cynicism. In “Dark Center of the Universe,” his takeaway was bleak.

Well, it took a lot of work to be the ass that I am

And I’m really damn sure that anyone can

Equally, easily fuck you over

I don’t know what he meant, if he meant anything at all, but I know what it meant for me: It felt bad to betray people and become that kind of person. I tried to be nice, but the lying made me ugly, and withholding information, as my dad always said, was a kind of lying. If I couldn’t say certain things out loud—about my addiction, my arrest, how I’d hidden it all from Kari and friends—then I could at least sing this veiled reference. Brock’s lines offered me a first step.

In “Alone Down There” he screamed pained lyrics about death, which is what loneliness can feel like, but he seemed to direct these lyrics to a corpse and to his evil side:

The flies, they all gather around me

And you tooWell, I don’t want you to be alone down there!

To be alone down there, to be alone!

“Tiny Cities Made of Ashes” captured my disdain for mainstream America, which was ultimately my disdain for Phoenix, and the way my twenty-something self believed corporate interests had ruined everything pure and individualistic: Coke-a-Cola, fancy spas, plastic, the masses. Humanity treated our world as our ashtray. Brock sang:

Does anybody know a way that a body could get away?

Does anybody know a way?

Moving to a different city was my way, but maybe I’d misled myself. The album title itself was a nod to the only places in Earth’s orbit that had yet to be branded and co-opted by capitalist interests: the moon and the frozen continent.

If his lyrics were any reflection, Brock and I were a bit alike, sharing the same desire to spend time on those desolate outposts, getting some space from ourselves and humanity. After “Tiny Cities Made of Ashes” came the song “A Different City,” where he sings:

I wanna live in a city with no friends or family

I’m gonna look out the window of my color TV

I wanna remember to remember to forget you forgot me

I’m gonna look out the window of my color TV

I was about to have that. I wanted to lose myself, too, and I wanted others to forget about me for a while so that I could find myself again. It hurt so hard to sing “I want to live in a city with no friends or family” because those people had always been my world. Then again, everything hurt. That’s partly why I loved the album’s bleakness. But musically, I also loved its rhythms and aggression: Brock screaming then going calm, screaming then going calm, how tranquility coexisted with rage, and how he let himself repeat the cycle. The slowest songs sounded as desolate as Antarctica. That downer combination captured my waking life.

After all that bleakness came “Paper Thin Walls,” this peppy song mixed with melancholy, like an attempt to lift the spirits, or maybe a moment of joy. I mean, clearly this band enjoyed a good dance. It’s not like they were depressives. The way the drummer played, you could tell he liked a good booty-shaking beat. This song was a little fun groove to brighten things up, but then the sad bridge came in, and you knew the light was just a blip.

After Lee went to work, I drove straight to my favorite little record store to buy this CD. It became the soundtrack to my summer. I needed it and hated it. I listened the way you pick a scab: No matter how much it hurt, I couldn’t resist the pain.

After a few days listening, the music had burrowed under my skin, and I wondered: Who was this band? The answer didn’t surprise me: They came from the Northwest.

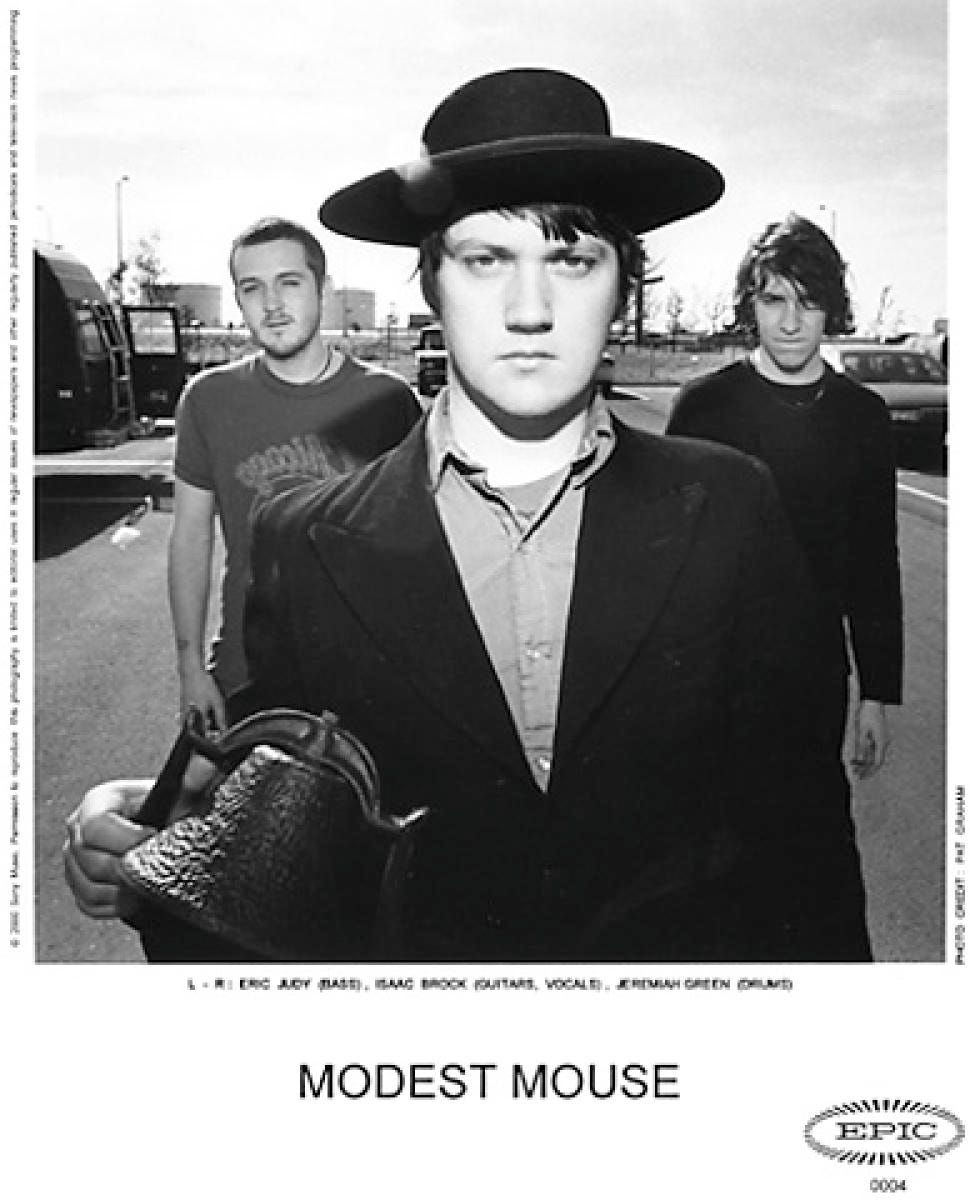

Singer-guitarist Isaac Brock, drummer Jeremiah Green, and bassist Eric Judy formed the band in Issaquah, Washington in 1992. Judy met Brock at the little family video store where he worked outside of Seattle. Green lived right outside of Seattle, too. As one of a slew of post-Grunge bands from little Northwest towns, the band made sure they mentioned they came from Issaquah, on the outskirts of Seattle, so they couldn’t be pigeonholed with Seattle music associations or reduced to members of some manufactured “scene” the way bands had been labeled Grunge in the ’90s.

They made their first EP with Calvin Johnson of the legendary K Records in 1994 and released a single for Sub Pop. They followed those early recordings with sophisticated albums that wowed listeners outside of the Northwest, including This Is a Long Drive for Someone With Nothing to Think About in 1996, and The Lonesome Crowded West in 1997. They toured regularly, crisscrossing the country in a beat-up van that constantly broke down and that singer Isaac Brock had to regularly fix. And they built a reputation in an era before social media and smartphones, when fans got to know new bands by seeing them perform, and through word of mouth—just like I had found them.

While I was on probation, Modest Mouse was busy recording The Moon & Antarctica between July and November in 1999. They released it on June 13, 2000.

In September 2000, the Phoenix New Times wrote an article called “Mouse on the Moon” about them, that answered many of my questions when I found it.

At that time, Brock rented a house in tiny Cottage Grove, Oregon, of all places, two hours south of Portland. “No one’s on the streets,” Brock told The New Times, “the Wal-Mart closes at 9 o’clock, no one cares who you are, and there’s absolutely nothing to do.” He’d just woken up from an afternoon nap to do the interview, after drinking beer that morning. The band had just signed to a big label that afforded them a $100,000 recording budget, so he had that luxury. “[Epic] may have given us some money,” Brock told the reporter, “but they’re damn sure they ain’t the boss of me, and there’s no way they’re gonna interfere with our live show.”

After recording previous albums in the Northwest, they asked their musician friend Brian Deck to produce their next album. Deck and his friends were building Cava Studio in Chicago.

“My mind wasn’t too heavy on the fact that [Epic] was a change,” Brock told Yahoo decades later. “I do remember one thing that affected my thinking: I really didn’t want to come out of the gate alienating everyone. Now I look at it and am like, ‘Why the fuck should anyone care?’ But it was important to people that, if you’re no longer an independent band, [you don’t] start making easy crap [and do] a pop version of yourself. I wouldn’t say I was self-conscious, but I was aware that I didn’t want it to sound like we were pandering to radio or something.”

So Modest Mouse recorded demos with producer Phil Ek out West, practicing in his basement. They shaped the songs in preproduction in Seattle, then they drove to Chicago ahead of schedule and arrived while staff was still building Cava Studio, literally, from the ground up. As they recounted in an oral history at Yahoo:

Deck: The Modest Mouse record was the first thing we recorded there. They were so excited to start recording that they started driving early. A couple weeks before I expected them, they showed up—and helped us hang drywall.

Brock: My friend who’d driven out with me helped hang drywall. I’d like to say I helped, but I sat at a desk.

Deck: It was embarrassing and terrifying to have my first major-label band show up and not have the recording studio finished being built. It’s a pretty complex thing. Typically you test shit out before your first client shows up. Rather than get the chance to test it out, they finished building it.

Jeremiah Green: [Eric] and I drove out to Chicago together to do our part of that recording. We had this apartment above the studio. There were three rooms: Isaac and his girlfriend were in one; Eric and I in one; this dude Ben Blankenship [in another].

Brock: He was this dude from around town who claimed to know how to play a lot more things than he did. Or maybe he just didn’t know how to incorporate them into what we were doing. The band was a little free form as far as people coming and going. It wasn’t something we really thought about much, like, “We’re adding a new band member!” and chiseling their name on the fucking foundation in stone.

Green: Ben would get extra creative, to the point where people would be like, “What are you doing? You’re wasting our time.” But the end result would be this cool thing. I remember [on “Paper Thin Walls”], he tuned up like five guitars to different chords so he could play this part on each guitar. It’s just this simple part that happened twice. These days, we have more of a budget and time to do stuff like that. But at the time, it was like, “We’re gonna take three hours to record this one part of the song?” It seemed wacky. But it was cool.

Brock: He’d just walk by and play each note, and it would ring out. That’s the one thing I remember him doing that I thought was great.

Then the night before they were going to start tracking Brock’s vocals, he got drunk at The Empty Bottle and got punched in the face by some strangers in the park outside. They broke his jaw. He wasn’t picking a fight. He just said “Hey, how are y’all doing?” to the 15 people who were hanging out there. “You know, I think that I’m a real suave guy while drunk,” he told The New Times, “so I just thought I’d go talk to some kids.” From the corner of his eye, he saw something fly at his head. When that fist broke Brock’s jaw, they started throwing beer bottles.

“The local kids were very possessive of their spot,” Brock told Yahoo. “They didn’t want a bunch of fuckin’ weirdos in their neighborhood. I didn’t read the room right. …I remember I would move my head to the left or right and a bottle would slo-mo by. It was a really good punch; my hat’s off to the fella. That neighborhood has one of the leading Golden Glove boxing establishments. Those kids know how to hit someone. My mind hadn’t kicked into, ‘Also they might just kill me.’ But I knew I didn’t want any more of what I just got. [They yelled] ‘Fuck you, cowboy!’ I remember being like, ‘Cowboy?’ I looked down and was like, ‘I’m wearing a Western shirt. I guess not everyone wears Western shirts.’”

His injury changed the way they made the music.

“But having my jaw broken was great in respect to its effect on the album,” Brock said, “because I had to take a different approach to recording. Usually when we record, we lay down the basic tracks, and I feel guilty if I don’t hurry up and get the vocals done. But this time I couldn’t sing. So I just hung out, wrote a lot more instrumentals, and had a chance to really listen and work on it before laying down the vocals.”

Deck: I didn’t find out until the next morning that he went to the hospital and had surgery and they wired his jaw shut. I believe his jaw stayed wired shut for six weeks. I made him rough mixes onto a cassette tape, and he listened and listened in the hospital. I think that’s when he decided it wasn’t done. I don’t know if it didn’t fulfill a vision he had or if he had a greater vision for what it could be. The record we’d made up until that point was more production-y than their previous records—there were more layers already. But there was nothing near the amount of guitars and vocals that ended up on the finished product. When his jaw was still wired shut but his energy had returned and he felt OK again, he said, “I think we’re not finished with this instrumentally. I’d like to get back in there and keep recording.” I remember him telling me this in the kitchen of my apartment. I said, “Are you sure? Wow. I thought we worked really hard on that and nailed it.” He said, “I think there could be a lot more.” That’s when we started to turn it into the record that it is.

Rutili: I think having all that extra time waiting for his jaw to heal made the record better.

Brock: I felt like it needed a lot of work. Once I got my mouth wired shut, singing kinda wasn’t an option. I was stuck inside—the folks who broke my jaw were looking for another shot at it. I wasn’t able to work on vocals, so I spent a lot of time just adding shit.

What about those lyrics? “That’s my one rule,” Brock told The New Times. “I don’t talk about lyrics.”

They eventually licensed “Gravity Rides Everything” for use in a Nissan Quest minivan commercial, which caused some blowback from fans who still clung to the very ’90s ideas of “selling out,” but Brock owned the decision as a necessary financial one. “People who don’t have to make their living playing music can bitch about my principles while they spend their parents’ money or wash dishes for some asshole,” he said.

Amid all of these crazy details, his age stuck with me. He was 25. The music sounded like it came from someone much older. When you’re young and love bands, the musicians always seem so much older than you. Everyone does. Because 50 seems ancient, 30-year-olds seem wise and worlds apart from you. Then when you age, you look back and realize those bands that blew your mind on stage—the ones that defined your youth—were actually younger than you are now. They were old enough to drink at the bar at an all-ages show, but they were often too young to have children, too young to own houses, too young to be forced into getting “real jobs” if this music thing quit working. They were renters. They drove beat up cars and borrowed money from their parents and washed dishes at restaurants. They weren’t as old as they seemed to your teenage self. Because they made such powerful music, they seemed more advanced, but it turns out, they didn’t have it all figured out the way you thought they did. Only in my mid-30s would I start to see that.

At age 25, I read The New Times and my mind exploded: How was this music coming out of a kid like me? How did such a fuckup write poetry like that? How did he have such insight and play guitar that well? I couldn’t even finish a draft of one essay. I felt passion, but passion wasn’t enough. Art required skill, and I didn’t practice writing consistently enough to have skill. This 25-year-old from the trailer park seemed to have it all. It took me years to catch up. By the time I started publishing essays in tiny ass, non-paying literary magazines, this dude had become internationally famous, and bought his own house with the money he earned from touring and licensing his music to film and TV. I still worked retail and rented an apartment.

When Lee and I saw that the band was playing Nita’s Hideaway in Tempe in October 2000, we went.

That year, The Phoenix New Times named Nita’s the best club for rock music. “From electrifying outdoor sets by The Flaming Lips and Modest Mouse to indoor shows from Delta 72 in Calexico,” they said, “the tiny club has solidified its reputation as one of the few places willing and able to take a chance on progressive acts.… Add to that a stellar ambience in a weight stuff that is nothing if not engaging, and you have hands-down the best place to enjoy rock in the Valley.”

I saw some great shows at that time: Weezer playing the full blue album in 2000; Calexico opening for Pavement in 1999; Calexico playing in a Tucson art gallery in August 2000; Man or Astro-Man playing in the Nita’s parking lot in 2000; The Flaming Lips playing that same parking lot to a small crowd on their The Soft Bulletin tour, before they toured with Beck and got huge; and Beck play the Midnite Vultures tour in 2000. Seeing shows wasn’t enough. I had a great digital camera that I’d started filming shows with. After a decade of recording shows on shitty handheld audio equipment, I was thrilled to upgrade to something professional that captured the fidelity and energy more closely. Of course, I filmed Modest Mouse.

By then, things were finally happening in my life. I had landed a job at Powell’s Books in Portland and was set to begin in November. I’d found myself an apartment up there. I’d boxed up all my belongings and paid some movers to drive most of it up, then two days after the Modest Mouse show, I planned to drive my little Toyota pickup truck and cats and the rest of my belongings all the way to Oregon. That meant I barely have enough time to catch the show.

Modest Mouse had played Nita’s the previous June, outdoors in the parking lot. People filmed it. It looked energetic. This time they played inside. It was intimate. And loud.

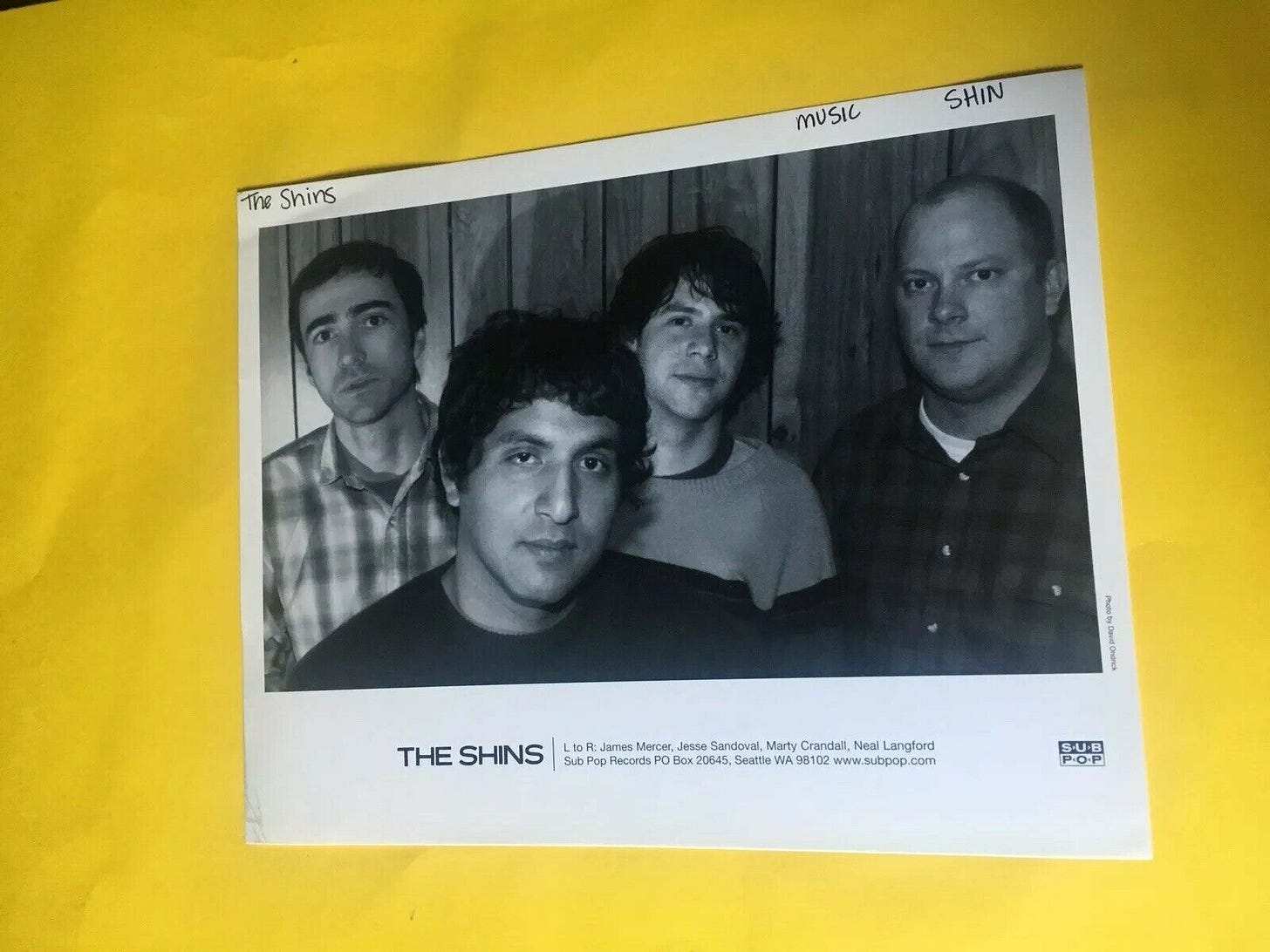

Lee and I arrived early enough to catch the openers: a dude from San Diego called Black Heart Procession, and another band named The Shins. They lived in New Mexico, but their profile and lives were about to change. Sub Pop’s cofounder Jonathan Poneman saw their show in San Francisco on this tour and quickly offered them a record deal. But that night in Phoenix, The Shins had no label, and few people outside of their native Southwest had heard of them. I don’t remember much about their set except it was loud and had too much keyboard. I never would have guessed that their music would end up on a movie soundtrack that would help define the subsequent decade the way the Singles soundtrack had shaped the early ’90s. Only years after I and everyone else fell in love with Oh, Inverted World did I realize that the band on the Garden State soundtrack was the band whose keyboards dry-humped Modest Mouse’s drum set at the show I filmed. I wish I’d filmed The Shins’ set, too. A few years later, Shins drummer Jesse Sandoval would run a New Mexican food cart up in North Portland’s Mississippi district, and I’d buy burritos from him twice before I figured out who he was.

When Modest Mouse set up, Lee got himself a beer at the bar, and I positioned myself by the stack of speakers by the second guitarist, giving me a clear shot of Brock, the drummer, and the bassist all in the frame. By 2000, digital cameras had started getting popular, and people started bringing them and little handheld video recorders more frequently to shows. So by 2000, security had relaxed a bit on recording equipment, letting people film and snap photos in a way that would’ve made the world better in 1993. Unlike most shows I recorded in the ’90s, I openly filmed this one, so I captured the whole thing perfectly, with no obstructions from any fans’ heads or waving hands, no hassles from security, and clear audio.

Modest Mouse were like emissaries from the Northwest, confirming my decision to move there. They dressed for a Northwest winter here in the warm Phoenix fall: cuffed dark jeans, big black boots, and tees. Among all the Warped Tour looking Phoenix dudes and the guys with Dropkick Murphy’s shirts, they stood out: cool, modern, urbane, futuristic. I thought: I could dress like that, too.

Brock took the stage first and plucked his guitar strings, tinkering with his effects pedals to lay down a looping sheet of guitar sound. As it rang through the club, the band came through the back door and took the stage, the drummer Jeremiah Green pounded the set, and they tore into a raging version of “What People Are Made of.” They didn’t relent for an hour.

The veins in his neck stuck out as he sang.

Modest Mouse’s performance left the crowd stunned.

When the band walked out the club’s backdoor to their own guitar feedback, Lee and I walked out with them. They took my whole childhood with them. That old Seattle shit was dead. So was my old self. It was time to move on. There they were: standing by their tour van by the back door, smoking cigs and drinking beer. Brock told people Hey, thanks for coming.

Modest Mouse quickly graduated to huge venues and never played such intimate clubs again. And The Shins would soon become of the biggest bands in the world.

My transformation was personal.

For me, the ’90s ended right then in Nita’s, with Brock singing “And that’s how the world began / And that’s how the world will end,” because two days later, I made good and left for Oregon.

I took a leisurely week to drive through California to Oregon with my cats. I arrived in fall, cool but still sunny, and arrived during the end of what I call old Portland. It wasn’t the Portland of Voodoo Donuts or Stumptown coffee or food tourism. It was the Portland where the decommissioned Henry Weinhardts brewery, not Whole Foods, still stood on Burnside next to Powell’s Books where I worked. It was the Portland where the hotel they shot part of Drugstore Cowboy was still a fleabag rental rather than an Ace Hotel, where you didn’t need to go far north of Burnside for drugs, because there was no upscale Pearl District there. Neither the term nor the place existed yet. Portland was cheap. It was awesome. It changed very soon after my arrival. But the cool kids dressed like Isaac Brock did that night at Nita’s. Before bands like Modest Mouse and The Shins became some of Portland’s biggest exports, those musicians were just ambitious transplants like me, attracted by a great cost of living and a powerful cultural energy, and the desire to make art with low overhead. They succeeded wildly and make their living from music. I didn’t fare as well financially. I’m a small literary voice here, but it is a voice, and I did what I came to do, personally and creatively. I’ve been drug-free for 21 years, and I’m still writing up a storm.

I never got any deeper into Modest Mouse that this album. Their other songs played everywhere around Portland back then. You couldn’t escape them. They were great songs, too. I just didn’t need them like I needed Moon.

Their music still plays all over town. I like to joke with my wife that our daughter will hear The Shins’ song “New Slang” and Modest Mouses’ “The World at Large” in coffee shops for the rest of her life in Portland, so we inoculated her early by playing those songs for her at age two.

In 2005, while I was working at Powell’s Books, The Smiths’ guitarist Johnny Marr appeared in the Rose Room information desk, asking for directions. I worked in the Rose Room. I had just been standing at that information desk. A coworker excitedly told me they’d just given Marr directions to a different room, and when I pulled my jaw off the floor, I scanned the aisles and spotted him, with his handsome jaw line and lush hair, strutting into the Orange Room. I watched him pass like a sasquatch in that famous grainy footage. Johnny Marr, I thought, the guy whose guitar changed my life in sixth grade. Glad to see he’s a reader. Every literary musician who toured through Portland came to Powell’s: Nick Cave, Glen Danzig, Henry Rollins, Donovan, Thurston Moore. Years later Marr’s other reason emerged: He’d played a few shows with Modest Mouse. Once he hit it off with the band, he wrote their fifth studio album We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank with them. Turns out that we’d spotted him at Powell’s during their early courtship phase, before he’d committed to recording and touring as a band. “Isaac contacted me and asked if I’d help Modest Mouse write the new album,” Marr said on his website. “I was intrigued and played with the band in Portland a couple of times. We hit it off and wrote three great songs straight away, something clicked, it felt right from the off. I have a new Healers album pretty much done, but we’ve been having such a good time playing these new Modest Mouse songs. When people hear the record they’ll see why, we’re very good together.”

That was the kind of thing I moved north for.

To my surprise, I couldn’t rewatch my footage of the Modest Mouse show for over 10 years. The music was too connected to a time. It brought back too many painful memories, not specific incidents, but the general dark feel of that brief part of my life in Arizona. The tape sat in a box of other mini-DV tapes containing live shows I’d taped in 2000 and 2001. I feared the tapes had degenerated. I knew the show was powerful and footage looked great. I knew other fans would want to see it, too. But I’d also captured a difficult time, and I wasn’t ready to revisit it. That was me being avoidant, and avoidance was one of my unhealthy traits I was working on as an adult. So I finally rewatched it, I got it digitized, and 20 years after the fact, I shared it on YouTube. As one fan commented, “I had no idea this video existed. I love it. Thank you! It’s like watching movies of my dreams.” Me, too. When I watch the show now, I’m watching a piece of my old life when no photos exist.

Kari stayed in Phoenix and started a family. She seems very happy there.

And that Sierra magazine contest essay that I struggled to write in Phoenix, called “What if John Muir Had Fallen in Love With the Central Valley Instead of the Sierras?” I never completed it. But I ended up turning my interest in that part of California into a whole book, entitled The Heart of California: Exploring the San Joaquin Valley. It took 20 years to get it right, but I got it.

As if to lift the desultory mood of that time, I listened to The Flaming Lips’ 1999 album, The Soft Bulletin, a lot, too. Looking back, what The Flaming Lips singer Wayne Coyne said about that album applies to my time with The Moon & Antarctica. “Everyone talks about it being a sad record, but I don’t think of it as a sad record. I think of it as a record where you’re just thinking about life, and death is part of life.” When Cohen listens to The Soft Bulletin now, he says, “it really is about despair, but there’s no despair in it. What I mean by that, sometimes you think you want to sing about despair, but I don’t think it’s like that. I think it’s being in despair and singing. When you’re in despair you think, Oh, I’m fine. Everything’s good. Look, the sun’s coming out. Look at that. Isn’t it great? I think that’s what The Soft Bulletin is doing.”

I know exactly what he means.

Great stuff, Aaron. I had my own "WTF am I doing in Arizona?" moment a few years earlier and about a hundred miles north in Flagstaff.

Wow, great read. I just found this article by chance, but I really enjoyed the whole thing. I'm also a recovering heroin addict. I've been on methadone.......13 years.... BUT in those thirteen years I've stayed "clean" minus the methadone of course and bought a home with my partner of 9 years and done a lot of work on myself. But the next step is getting off methadone. My highest dose was 240mgs, yes you read that correctly. And now I'm at 110mgs. I'm also a lifelong guitar player and I also picked up drums 8 years ago. I've loved modest mouse since i was 13 years old when my sister's friend gave her "This is a long drive..." and I quickly decided to take possession lol. Anyways thanks for posting this it was really a great read and very relatable for even more reasons than I've listed here.